Abstract

Background

Because of the increasing life expectancy in our society, aging-related neurodegenerative disorders are one of the main issues in global health. Most of these diseases are characterized by the deposition of misfolded proteins and a progressive cognitive decline. Among these diseases, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are the most common types of degenerative dementia. Although both show specific features, an important neuropathological and clinical overlap between them hampers their correct diagnosis. In this work, we identified molecular biomarkers aiming to improve the misdiagnosis between both diseases.

Methods

Plasma extracellular vesicles (EVs) -from DLB, AD and healthy controls- were isolated using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and characterized by flow cytometry, Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and cryo-electron microscopy. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and related bibliographic search was performed and a selected group of EV-associated microRNAs (miRNAs) was analysed by qPCR.

Results

Results uncovered two miRNAs (hsa-miR-451a and hsa-miR-21-5p) significantly down-regulated in AD samples respect to DLB patients, and a set of four miRNAs (hsa-miR-23a-3p, hsa-miR-126-3p, hsa-let-7i-5p, and hsa-miR-151a-3p) significantly decreased in AD respect to controls. The two miRNAs showing decreased expression in AD in comparison to DLB provided area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.9 in ROC curve analysis, thus suggesting their possible use as biomarkers to discriminate between both diseases. Target gene analysis of these miRNAs using prediction online tools showed accumulation of phosphorylation enzymes, presence of proteasome-related proteins and genes involved in cell death among others.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that plasma-EV associated miRNAs may reflect a differential profile for a given dementia-related disorder which, once validated in larger cohorts of patients, could help to improve the differential diagnosis of DLB versus AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neurodegenerative disorders with largest economic burden in our society include dementia syndromes such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and movement disorders namely Parkinson’s disease (PD), in which about 50% of patients may develop dementia 15 years after PD onset [1,2,3]. Clinically, along the course of the three diseases, a progressive cognitive decline affecting the normal and social functions of the patients is observed [4]. Moreover, neuropathologically, a common neurodegeneration-related feature is the deposition of misfolded proteins. While in DLB and PD α-synuclein accumulations, named Lewy bodies are found [5], in AD –and also in about half of all DLB cases- ß-amyloid senile plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau are accumulated in the brain [6, 7]. Correspondingly, DLB shows an important neuropathological and therefore clinical overlap with both, PD and AD, hampering its correct identification. Currently, a high proportion of DLB cases are missed or misdiagnosed as AD, resulting in an incorrect treatment of the patient, which leads to the development of adverse reactions in 50% of these treated patients [7].

Over the past decade, the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in the development and functioning of the central nervous system has been deeply explored [8,9,10]. EVs, such as exosomes (EXs) and microvesicles (MVs), seem to be important effectors in the development of cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. They have been shown to mediate the transport of prions and misfolded pro-aggregating proteins from cell to cell [11,12,13,14]. Because EVs are produced by each individual cell and provide a protected environment to shuttle not only proteins but also microRNAs (miRNAs) to the intercellular space and to different body fluids, the study of their content has emerged as an area of interest in the biomarker field, also in neurodegenerative disorders [15,16,17,18]. To date, several EV-associated miRNAs have been identified as altered and related to neurodegenerative disorders [19,20,21]. Many of these studied EVs were obtained from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples. However, due to several issues on CSF-collection (difficulty, invasiveness, morbidity, risk), alternative sources such as plasma-derived EVs have been lately reported [22, 23].

In this study, we analysed the miRNA profile associated to plasma-derived EVs from DLB, AD and healthy controls. We further investigated whether differences in the plasma-EV-miRNA content could be of help to better characterize neurodegenerative disorders, specifically DLB and AD. Our data suggest that some plasma-EV associated miRNAs are differentially found in DLB and AD patients, and thus could help to improve the differential diagnosis of these overlapping neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and methods

Blood collection and sample processing

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our institution approved the following protocol and from each subject, written informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles [24]. DLB patients (n = 18; age range 62–84 years; mean 72.5 years; male: female ratio 1:1.75) were recruited by neurologists specialized in Lewy body disorders at the Dementia Unit, Department of Neurology from the University Hospital Bellvitge, (L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona). Diagnosis of DLB patients was established according to the 2005 DLB Consortium Criteria [25], and the age at onset was defined as the age when parkinsonism or memory loss was first reported by patients’ relatives. A group of age- and gender-matched healthy individuals (n = 15; age-range 61–85; mean 70.5 years; male: female 1:2) from the same hospital were also recruited. Finally, a group of AD patients (n = 10; age range 62–80; mean 71; male: female ratio 1:1.5) was enrolled by the Neurology Department of the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol. AD diagnosis was assessed following the 2011 revised criteria from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association [26]. These patients presented a Global Deterioration Scale of 4.3 ± 1.2 degrees. Clinical data of all patients and healthy controls enrolled in this study are shown in Table 1.

Blood samples from all participants were obtained following ISEV- International Society for Extracellular Vesicles- guidelines [27] and applying the same collection protocol in both hospitals. In short, 15 mL of peripheral blood were collected by venous puncture using a 21-gauge needle coupled to a butterfly device and using sodium citrate pre-treated tubes (BD Vacutainer, New Jersey, USA) as described previously [28]. After discarding the first 2–3 ml, blood was collected and mixed with the anticoagulant by gently inverting tubes gently. Samples were processed within the first 2 h after collection. Plasma was clarified of platelets and cells by consecutive centrifugation steps at 500 x g for 10 min, 2500 x g for 15 min and a last step at 13,000 x g for 10 min. Plasma samples were frozen in a freezing container with freezing rate of - 1 °C/min and kept at − 80 °C until EV purification. Samples did not suffer from more than 2 freeze-thaw cycles.

EV isolation by size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) was used for isolating plasma-EVs as previously described [28]. Briefly, Sepharose-CL2B (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was stacked in a Puriflash column Dry Load Empty 12 g (20/pk) from Interchim (France)-Cromlab, S.L. (Barcelona, Spain). Once the column was completely stacked, two mL of plasma (previously thawed on ice) were loaded onto the column and eluted with filtered PBS. A total of 20 fractions (0.5 mL each) were immediately collected.

EV characterization

EV fractions were characterized for their protein concentration, presence of specific EV-markers, size and morphology.

As published before, protein concentration for each SEC collected fraction was measured by absorbance at 280 nm in a Thermo Scientific Nanodrop® ND-100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Also, SEC-fractions were analysed for the presence of CD9, CD81, CD63 and CD5L as specific EV-markers by bead-based flow cytometry assay [28, 29]. Briefly, 50 μL of each fraction were incubated with 0.5 μL aldehyde/sulphate-latex beads-4 μm (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 15 min at room temperature, re-suspended in coupling buffer and incubated overnight. After two washing steps with the same buffer, EV-coated beads were incubated with anti-CD9 (Clone VJ1/20), anti-CD63 (Clone TEA 3/18), anti-CD5L (ab45408 from Abcam) and anti-CD81 (clone 5A6, from Santa Cruz Biotech) or polyclonal IgG isotype (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 30 min at 4 °C. After a washing step, samples were subjected to 30 min incubation at 4 °C with a FITC-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) for CD9, CD81 and CD63, and secondary Ab anti-rabbit AlexaFLuor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for CD5L. Two final washing steps were performed before analysing the samples by flow cytometry in a FacsVerse cytometer (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values were plotted (Flow Jo software, Tree Star, Ashland, OR) and tetraspanin-positive fractions with the highest MFI (fractions 10–12 from our SEC column) were considered as EV-containing fractions and pooled for the forthcoming analysis.

Aiming to check EV morphology and size, EV-enriched pools were also subjected to cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and to Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) (n = 6), as reported earlier [28].

Isolation of microRNA

A volume of 750 μL of pooled EVs from each sample was lyophilized at − 23 °C /overnight and used for miRNA extraction using the miRCURYTM RNA Isolation Kit-biofluids (Exiqon Vedbaek, Denmark) at room temperature as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, lyses solution and protein precipitation solution were added to each sample. After incubation at room temperature for 1 min, samples were centrifuged at 11,000 x g for 3 min. Isopropanol was added to the supernatants and the mix was transferred to the provided columns. After a first centrifugation at 11,000 x g for 30 s, several washing steps at the same centrifugation speed with 1BF and 2BF solutions were applied. The column was subjected to a last 2 min centrifugation to completely dry the membrane. MiRNA elution was performed by adding 100 μL of RNase-free H2O directly onto the membrane and centrifuging it for 1 min at 11,000 x g. The obtained material was kept at − 80 °C until further analysis.

In samples utilized for RT-qPCR validation experiments, 2 artificial RNAs (UniSp4 and UniSp5 from the RNA spike-in kit, Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) were spiked into the lysis buffer before miRNA purification, according to the manufacturer’s protocol enabling the assessment of miRNA purification and amplification efficiency.

MicroRNA discovery by next generation sequencing (NGS) and raw data analysis

The total volume of the obtained miRNAs from 7 DLB and 7 control samples was precipitated overnight at − 20 °C with 1 μL of glycogen (20 μg/ μL), 10% 3 M AcNa (ph 4.8) and 2 volumes of absolute ETOH. miRNAs were re-suspended in RNase free H2O and heated at 65 °C for 2–3 min. Quality control and size distribution of the purified small RNA was assessed by Bioanalyzer 2100, (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA).

The whole precipitated volume of each sample (10 μL) was used for library preparation by NEBNext Multiplex Small RNA Sample Preparation Set for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Massachusetts, USA) following kit instructions. Individual libraries were subjected to the quality analysis using a D1000 ScreenTape (TapeStation, Agilent Technologies), quantified by fluorimetry and pooled. Clustering and sequencing were done in an Illumina Sequencer (MiSeq, Illumina, San Diego, USA) at 1 x 50c single read mode and 200,000 reads were obtained for each sample. Obtained FastQ raw data were analysed as follow: (1) Trimmomatic was used to remove the adapter sequences from the reads [30]; (2) Reads were mapped to the human genome using Bowtie2 algorithm and individual miRNAs were identified [31]; (3) For each sample, the number of reads mapped to a particular miRNA sequence was counted; and (4) the total count of reads was normalized applying the weighted trimmed means of M-values (TMM) [32]. Before differential expression analysis, Lilliefors’ composite goodness-of-fit test, Jarque-Bera hypothesis test and Shapiro-Wilk test were applied to check the normality of our samples.

For NGS expression analysis the following criteria were followed: at least minimum of 5 reads per sample when present to considered a miRNA as present; present in all patient samples (minimum of 5 reads) and absent (less than 5 reads) in more than half of the control cohort; present in all control samples and absent in more than half of the patients for presence/absence consideration; present in most samples from both cohorts but differentially expressed between both groups. Differential expression analysis for DLB versus control cohorts was performed by Wilconson-rank sum test (p-value < 0.05) [33] and validated by the Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation methodology.

Bibliographic search and miRNA selection

Literature search based on PubMed and The Nervous System Disease NcRNAome Atlas (NSDNA) [34] databases was performed aiming to identify miRNAs already described as deregulated in dementia and neurodegenerative disorders. We then combined this bibliographic information with our data from NGS results in plasma-EV from DLB and healthy control samples. Thus, a group of 15 highly represented miRNAs (all of them producing more than 5000 reads in the NGS assay and belonging to the top most abundant miRNAs identified by NGS) were further considered for expression studies to compare AD and DLB by qPCR.

Reverse transcription and qPCR analysis

MiRCURY LNATM Universal cDNA synthesis Kit II and miRNA PCR system Pick & Mix (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) were used for cDNA synthesis and qPCR validation analysis of the selected miRNAs according to the manufacturer’s instructions (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for further purchasing information). Due to the low concentration of genetic material associated to vesicles, 2 μL of undiluted miRNAs were used for retrotranscription at 42 °C for 60 min. A third spike-in miRNA (UniSp6) from the same kit (Exiqon) was used as retrotranscription control. After enzyme inhibition at 95 °C for 5 min, cDNA was diluted 1:80 and 4 μL were used for qPCR reaction with ExiLENT SYBR Green Master Mix (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) on a LightCycler 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), following kit’s instructions. For each sample, miRNAs were analysed in duplicate and the mean value was used in next data analyses. Amplification of the used spike-ins (UniSp4, UniSp5, and UniSp6) was performed in the same PCR pre-designed panels (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) with an interplate calibrator control miRNA (UniSp3).

Data analysis and statistical testing

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA).

Regarding EV characterization, MFI values for EV-markers, EV-concentrations, and EV-size are given as mean ± SD. Two-tailed unpaired T-test was applied (p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant).

For qPCR analysis, Cq (quantification cycle) values were determined for each qPCR and the average of duplicates was obtained. The variability between the different plates was corrected by the Cq values for UniSp3 as interplate calibrator. As stable genes, RNA-isolation control spike-in UniSp4 and the retro-transcription control spike-in UniSp6 were considered as reference genes. The average of the two Cq values was used as reference value to calculate miRNA expression. Relative expression in DLB and AD was estimated compared to healthy controls and represented as fold expression changes obtained by 2-ΔΔCt. Considering the low number of samples, multiple comparisons between the three groups (DLB, AD and controls) were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test and Dunn’s test was used for multiple corrections. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. One-variable area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated considering the expression change in order to assess the possible diagnostic potential of each differentially expressed miRNA by the Wilson/Brown method (GraphPad Prism v7; 95% C.I., AUC > 0.750 was assessed as minimum value to be considered as a good-potential biomarker).

We have submitted all relevant data of our experiments to the EV-TRACK knowledgebase (EV-TRACK ID: EV180020) [35].

microRNA target prediction

A list of possible affected target genes for the differentially expressed miRNAs by qPCR was obtained by miRGate [36] database. Filtering of the software output data was performed following the instructions of the developers. We first considered validated targets, named “confirmed predictions” and showing the number of confirmed databases of gene-miRNA biding supporting this prediction group in the output data. For the remaining suggested targets, we took into account the column named “computational predictions”, defined by the number of computational methods supporting this prediction group. These referred to genes bioinformatically predicted to be regulated by the given miRNA, although no validation has been reported. Target with more than one computational prediction were also considered [36].

The relationship between the miRGate validated targets (those predicted with more than 1 confirmed predictions) were analysed with String [37] and Panther Gene Ontology [38] Databases, obtaining an integrated clustered network based on biological processes, cellular components and KEEG (Kyoto Encyclopaedia of genes and genomes) Pathways. In both cases, default settings were used. In Panther GO-analysis, Fisher’s exact test was applied and Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used.

Results

EV isolation and characterization

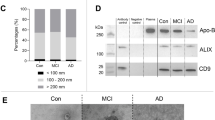

EVs were isolated from 2 mL of platelet-depleted plasma by SEC from three different cohorts (healthy controls, DLB and AD), obtaining 20 fractions of 0.5 mL from each sample. EV-fractions were identified by the presence of tetraspanins CD9, CD81, and CD63. Alternatively, some samples were also profiled for the presence of CD5L, recently described as plasma-EV marker [39]. In all cases, EV-enriched fractions –positive marked for the 4 EV markers used- were eluted, preceding the bulk of soluble protein (Fig. 1A i). Three fractions showing the highest MFI values of each sample were pooled for further experiments. No differences in MFI and expression of EV-markers were found between the three groups (Fig. 1A ii). Some samples were submitted to cryo-electron microscopy analysis confirming the presence of vesicles with the expected size and morphology (Fig. 1b). NTA data did not show any difference in particle concentration or particle size (Fig. 1c) between DLB and control groups.

Isolation and characterization of plasma-EVs. a EVs are eluted in low protein SEC fractions and EV-markers could be detected by bead-based flow cytometry. An example graph for one of the processed samples is shown (i); MFI values of the tetraspanins CD9, CD63 and CD81, and marker CD5L in the SEC-pooled fractions are represented. Bars represent mean +/−SD of 15 independent experiments in the case of tetraspanins and 5 in the case of CD5L (ii); (b) Cryo-EM images with characteristic shape and size of isolated vesicles; (c) above: representative NTA profiles for one control-EV and one DLB-EV sample, below: concentration and modal distribution for 6 control and 6 DLB samples (mean ± SD)

Discovery phase: miRNA profiles of DLB and control plasma-EVs

As first approach (discovery phase), 7 samples of DLB patients and 7 samples of age-matched controls were included for library construction and NGS analysis. An average of 4,364,157 ± 647,775 raw reads per sample was obtained for control samples (Additional file 2: Table S2); for DLB, we obtained 4,307,581 ± 2,076,192 reads per sample. Although 311 mature miRNAs were identified among all samples, only those showing at least 5 reads (n = 238) were further considered. More than 95% of these miRNAs were already included in vesicular databases EVpedia [40] and ExoCarta [41] as related to EV or exosomes from human samples (Fig. 2a). The hsa-let-7 family appeared as one of the most representative miRNA groups among our data set (Fig. 2b). The whole list of all identified miRNA has been submitted to the EVpedia database and entitled as this manuscript.

Statistical analyses of the 238 miRNAs identified by NGS showed no differences between DLB and controls (Wilcoxon p-value > 0.05 for all).

Selection of dementia related miRNAs for further qPCR analysis

Despite the lack of differences and statistical significance between DLB and healthy control cohorts, we carried out a bibliographic search for those miRNAs that yielded more than 5000 reads in the NGS experiment. Their association to dementia, DLB, AD and PD was examined and a group of 15 miRNAs (Table 2), mainly associated to dementia and AD, was further analysed by qPCR in three independent cohorts of samples.

Validation phase: qPCR analysis of selected microRNAs in DLB, AD and control cohorts

Three groups of samples including 11 DLB patients, 11 age-matched controls and 10 AD patients were used in the expression analysis by qPCR of the 15 selected miRNAs. Confirming our previous analyses by NGS, no differences were found for any of these miRNAs between DLB and healthy controls (Fig. 3).

MiRNA expression levels in DLB, AD and controls. MiRNAs with highest expression differences are shown first. From the 15 analysed miRNAs, a 6-miRNA group showed significantly down-regulated expression in AD samples when compared to the two other cohorts. In all cases, mean and range for fold change are plotted; (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005)

In contrast, two miRNAs were differentially down-regulated in AD patients compared to DLB and aged-matched controls (Fig. 3) – specifically hsa-miR-451a (p = 0.0003 and p = 0.0031, vs controls and DLB respectively) and hsa-miR-21-5p (p = 0.0075 and p = 0.0064). Moreover, four miRNAs were also significantly down-regulated also in AD compared to the control cohort (Fig. 3) - hsa-miR-23a-3p (p = 0.0016), hsa-miR-126-3p (p = 0.004), hsa-let-7i-5p (p = 0.0154), and hsa-miR-151a-3p (p = 0.0335)-. The remaining nine miRNAs (out of 15) did not show any statistical difference between the three groups, though three of them showed a trend to be over-expressed in AD compared to DLB and controls –hsa-miR-183-5p, hsa-miR-24-3p and hsa-miR-423-5p (Fig. 3). A predictive diagnostic value -based on ROC curves- to discriminate between AD and DLB patients rendered high specificity and sensitivity (AUC over 0.9) for the miRNAs hsa-miR-451a and hsa-miR-21-5p (Fig. 4).

microRNA target prediction and affected pathways

The six significantly and differentially down-regulated miRNAs in AD compared to controls and/or DLB were screened for their possible target genes using miRGate software. Up to 217 genes were predicted to be potentially regulated by these miRNAs and already validated as targets by 2 or more tools. These genes were further analysed and networked using String and Panther databases. Most of the analysed genes were related to metabolic processes (p = 1.6•10E-9), specifically protein metabolic processes (p = 5.1•10E-7). Among them, 37 were involved in the regulation of phosphorylation processes (p = 1.8•10E-6); specifically related to MAPK cascades and regulation of protein kinase activity (p = 0.009 and p = 1.2•10E-6, respectively). GO analysis for biological process also revealed the enrichment of response to stress (p = 4.3•10E-4), aging-related genes (p = 0.01), genes involved in neuronal morphogenesis and differentiation (p = 0.017 and p = 0.04, respectively). Particularly, several genes were related to negative regulation of neurogenesis and cell death (p = 0.003 and p = 0.01, respectively). Focusing in the analysis of the 2 miRNAs differentially expressed in AD vs DLB and/or controls, hsa-miR-451a and hsa-miR-21-5p, we found an enrichment of genes related to SMAD protein phosphorylation (p = 3.8•10E-5).

Additionally, we screened the whole list of predicted target looking for genes related to “neurodegeneration” and potentially regulated by these six miRNAs. The identified genes are listed in Table 3 and include ADAM10 (ADAM Metallopeptidase Domain 10), APP (β-amyloid precursor) and APPBP2 (amyloid protein-binding protein 2).

Discussion

DLB and AD show an important neuropathological, neurochemical and neuropsychiatric overlap, hampering correct DLB diagnosis, treatment and clinical management. Genetic and molecular characterization of these heterogeneous and complex disorders will lead to a better handling and diagnosis, although the definition of specific, differential and early biomarkers is still required. Plasma-EVs may become a promising reservoir of biomarkers also for neurodegenerative disorders. Besides their specific cell-derived content and the RNase-protected environment [15], EVs have been proved to cross the blood-brain barrier [10]. Therefore, although CSF would be the ideal source for specific biomarkers of central nervous system disorders, the difficulty, invasiveness, morbidity, and risk related to CSF-collection have paved the way for the analysis of plasma-derived EVs also in these pathologic scenarios.

In the current study, we analysed for the first time the miRNA content associated to plasma-EVs from DLB and AD patients compared to healthy controls. No differences in EV-markers, EV size, and morphology, or particle concentration were observed between the different cohorts. Our sequencing analysis focused on 238 miRNAs, most of them previously related to vesicles from human samples [40, 41]. Accordingly, the let-7 family accounted for around 54% of the identified miRNAs, as previously reported [77]. Overall, the NGS analyses of miRNAs did not reveal significant differences between DLB and aged-control samples.

Despite this lack of NGS significant results, a set of 15 miRNAs previously described in the literature as associated to neurodegenerative diseases and dementia were analysed by qPCR in an independent group of DLB and an additional group of AD patients compared to a different control cohort of neurologically unaffected individuals. Of notice, 10 of these miRNAs have been described among the most abundant miRNAs in the human brain [78]. No difference was observed in the expression of any of the analysed miRNAs between DLB and controls, as predicted by NGS results. However, 6 miRNAs (hsa-miR-451a, hsa-miR-21-5p, hsa-miR-23a-3p, hsa-miR-126-3p, hsa-let-7i-5p, and has-miR-151a-3p) were significantly down-regulated in AD patients compared to DLB or controls. Noteworthy, all these six miRNAs are also described as extracellular space- or exosome- associated in NCBI/Gene database. Our results are in line with previous observations on the reduced expression of hsa-miR-23a-3p in AD serum compared to controls [56] and the down-regulation of hsa-miR-126 previously described in CSF derived vesicles from AD patients [21, 51]. Besides confirming these previous studies, our expression results further indicate that DLB and AD patients may be distinguished by determining some of these miRNAs, as specifically shown by the expression profile of miRNAs hsa-miR-451a and hsa-miR-21-5p.

In comparison to healthy controls, hsa-miR-451a was previously described as down-regulated in CSF-derived AD-exosomes [55], and hsa-miR-21-5p was down-regulated in serum and CSF from AD patients [20, 42]. Therefore, both miRNAs were reported as putative biomarkers for AD. Here we confirmed the down-regulation of these two miRNAs also in plasma-derived EVs of AD patients compared to controls and, additionally to DLB. Finally, increased levels of hsa-let-7i-5p have been described in brain and CSF of AD patients [42, 50]. Also, up-regulation of hsa-miR-151a-3p has been reported in blood from AD patients in comparison to controls [44, 45]. These results are contradictory to our expression data that showed a reduced expression in AD versus controls in both cases. Having no reason to explain this later observation, it has been proposed that plasma and/or plasma-EV concentration of a given molecule including miRNA do not always show the same tendency [79], and the expression levels in peripheral circulation can also differ from those observed in CSF [42].

As a preliminary approach to evaluate the discrimination power of these miRNAs, ROC curves for the AD down-regulated miRNAs were calculated. Hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-451a rendered high AUC values to be considered a putative bio-signature for AD-DLB discrimination. Nevertheless, given the small number of samples analysed in this study, these results must be taken as tentative and as a first proof-of-concept, needing further validation in larger cohorts of patients. Likewise, it would be neither accurate to establish a specific correlation between miRNA levels and the clinical characteristics of the studied groups. Moreover, as plasma-EV associated miRNAs have been analysed, diverse causes, such as age, patient characteristics or the existence of concomitant pathologies in these aged patients, could also alter and modify these miRNAs, which seem to be deregulated.

It is known that different miRNAs can converge on the same function or be involved in the same molecular pathway. The deregulation and differential expression of these miRNAs in AD and DLB could be not only a cause or specific result of each disease, but a consequence of a common neurodegenerative process. Nevertheless, a preliminary target gene prediction for the 6 down-regulated miRNAs in our study defined a group of 217 most confirmed target genes (with more than 2 confirmed predictions), mostly implicated in metabolic processes and protein phosphorylation. The role of protein-phosphorylation during neurodegeneration has been widely described as important in the spread and accumulation of α-synuclein in DLB or PD brains [80, 81]. Also, the increased levels of phosphorylated tau in AD have been considered as an important marker of AD pathogenesis [82]. Specifically, genes involved in the Pl3K-AKt pathway, such as CAB39 [83], are among the predicted genes in our analysis. Together with AKT1, CAB39 would be possibly regulated by hsa-miR-451a. Therefore, our data suggest an impairment of this pathway, involved in neuron differentiation-proliferation and death [84]. Other genes related to neurodegeneration were also found, although with a lower prediction rate (Table 3). For instance, ADAM10, APPBP2 and APP, identified as hsa-let-7i-5p targets, are directly involved in the intracellular transport and deposition of β-amyloid peptides [85]. As inferred from our results, the reduction of hsa-miR-let-7i-5p, together with hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-151a-3p, could alter APPBP2 and APP expression resulting in an incorrect APP cleavage and promoting β-amyloid accumulation. Other genes like GSK3B (Glycogen synthase kinase 3) may play a role in neuroinflammation [86], neuronal apoptosis and accumulation of phosphorylated tau - in AD [87]. In our study, several miRNAs targeting GSK3B were down-regulated in AD samples. Furthermore, cell-death related genes, such as BCL2, cyclins involved in cell cycle or genes involved in the degradation of selective proteins (including β-amyloid peptide) such as proteasomal proteins were also present in the predicted network. The impairment of the proteasomal pathway would increase β-amyloid deposition and promote AD pathology [88]. Of notice, among the miRNAs and possible target genes differentially regulated in DLB vs AD (hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-451a) we found genes related to SMAD protein phosphorylation. The role of SMAD proteins in AD has been described, by the presence of smad2 within amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [89].

Altogether our data point to a specific reduced expression of AD-related miRNAs that would target genes primarily involved in protein phosphorylation cascades and the neuropathology of AD. The differential expression of these miRNAs in AD versus DLB patients could be considered as a putative biomarker for the identification/discrimination between both disorders, which could help neurologist to overcome the clinical and pathological overlap between AD and DLB. Nevertheless, as a first exploratory study, these data have to be further confirmed in larger cohorts of patients.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the comparison of the miRNA profile associated to plasma-EVs from DLB and AD patients. Despite the limited number of samples, our study provides preliminary evidence for different miRNA expression levels between the two most common types of degenerative dementia, with changes related to target genes and pathways involved in the pathogenesis of AD.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM10:

-

ADAM Metallopeptidase Domain 10)

- AKT1:

-

RAC-alpha serine/ threonine-protein kinase

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- APP:

-

β-amyloid precursor

- APPBP2:

-

Amyloid protein-binding protein 2

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CAB39:

-

Calcium binding protein 39

- CASP:

-

Caspase

- CCNE:

-

Cyclin E

- COX:

-

Cytochrome c oxidase

- Cq:

-

Quantification cycle

- Cryo-EM:

-

Cryo-electron microscopy

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DLB:

-

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- EVs:

-

Extracellular vesicles

- EXs:

-

Exosomes

- FTD:

-

Frontotemporal dementia

- GSK3B:

-

Glycogen synthase kinase 3

- ISEV:

-

International Society for Extracellular Vesicles

- KEEG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LOO:

-

Leave-one-out

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MFI:

-

Mean fluorescence intensity

- MIF:

-

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- miRNA:

-

Micro RNA

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- MVs:

-

Microvesicles

- NGS:

-

Next Generation Sequencing

- NSDNA:

-

The Nervous System Disease NcRNAome Atlas

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard desviation

- SEC:

-

Size-Exclusion chromatography

- TMM:

-

Trimmed means of M-values

- UBE2:

-

Ubiquitin Conjugating enzyme E2

References

Harada CN, Natelson-Love MC, Triebel K. Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):737–52.

Prince MJ. The global impact of dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, costs and trends. World Alzheimer report; 2016.

Ahmed RM, Paterson RW, Warren JD, Zetterberg H, O'Brien JT, Fox NC, et al. Biomarkers in dementia: clinical utility and new directions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(12):1426–34.

Przedborski S, Vila M, Jackson-Lewis V. Neurodegeneration: what is it and where are we? J Clin Invest. 2003;111:3–10.

Jellinger KA. Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease-dementia: current concepts and controversies. J Neural Transm. 2018;125(4):615–50.

Breitve MH, Chwiszczuk LJ, Hynninen MJ, Rongve A, Brønnick K, Janvin C, et al. A systematic review of cognitive decline in dementia with Lewy bodies versus Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:53.

Mark RE, Griffin WST. Dementia with Lewy bodies: definition, diagnosis, and pathogenic relationship to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(5):619–25.

Court FA, Midha R, Cisterna BA, Grochmal J, Shakhbazau A, Hendriks WT, et al. Morphological evidence for a transport of ribosomes from Schwann cells to regenerating axons. Glia. 2011;59:1529–39.

Lachenal G, Pernet-Gallay K, Chivet M, Hemming FJ, Belly A, Bodon G, et al. Release of exosomes from differentiated neurons and its regulation by synaptic glutamatergic activity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46:409–18.

García-Romero N, Carrión-Navarro J, Esteban-Rubio S, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Peris-Celda M, Alonso MM, et al. DNA sequences within glioma-derived extracellular vesicles can cross the intact blood-brain barrier and be detected in peripheral blood of patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:1416–28.

Kalani A, Tyagi A, Tyagi N. Exosomes: mediators of neurodegeneration, neuroprotection and therapeutics. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49(1):590–600.

Grey M, Dunning CJ, Gaspar R, Grey C, Brundin P, Sparr E, et al. Acceleration of α-synuclein aggregation by exosomes. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:2969–82.

Polanco JC, Scicluna BJ, Hill AF, Götz J. Extracellular vesicles isolated from the brains of rTg4510 mice seed tau protein aggregation in a threshold-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(24):12445–66.

Stuendl A, Kunadt M, Kruse N, Bartels C, Moebius W, Danzer KM, et al. Induction of α-synuclein aggregate formation by CSF exosomes from patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2016;139:481–94.

Bellingham SA, Hill AF. Analysis of miRNA signatures in neurodegenerative prion disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1658:67–80.

Marques TM, Kuiperij HB, Bruinsma IB, van Rumund A, Aerts MB, Esselink RAJ, et al. MicroRNAs in cerebrospinal fluid as potential biomarkers for Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(10):7736–45.

Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v4.27066.

Cheng L, Sharples RA, Scicluna BJ, Hill AF. Exosomes provide a protective and enriched source of miRNA for biomarker profiling compared to intracellular and cell-free blood. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;26:3.

Riancho J, Vázquez-Higuera JL, Pozueta A, Lage C, Kazimierczak M, Bravo M, et al. MicroRNA profile in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: analysis of miR-9-5p and miR-598 in raw and exosome enriched cerebrospinal fluid samples. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(2):483–91.

Burgos K, Malenica I, Metpally R, Courtright A, Rakela B, Beach T, et al. Profiles of extracellular miRNA in cerebrospinal fluid and serum from patients with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases correlate with disease status and features of pathology. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e94839.

Gui Y, Liu H, Zhang L, Lv W, Hu X. Altered microRNA profiles in cerebrospinal fluid exosome in Parkinson disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Oncotarget. 2015;6(35):37043–53.

Lugli G, Cohen AM, Bennet DA, Shah RC, Fields CJ, Hernandez AG, et al. Plasma exosomal miRNAs in persons with and without Alzheimer disease: altered expression and prospects for biomarkers. PlosOne. 2015;10(10):e0139233.

Cheng L, Doecke JD, Sharple RA. Prognostic serum miRNA biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease shows concordance with neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1188–96.

Lynöe N, Sandlund M, Dahlqvist G, Jacobsson L. Informed consent: study of quality of information given to participants in a clinical trial. BMJ. 1991;303:610–3.

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72.

Khachaturian ZS. Revised criteria for diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzh Dement. 2011;7(3):253–6.

Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;7:1535750.

Gámez-Valero A, Monguió-Tortajada M, Carreras-Planella L, Franquesa M, Beyer K, Borràs FE. Size-exclusion chromatography-based isolation minimally alters extracellular Vesicles' characteristics compared to precipitating agents. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33641.

Lozano-Ramos I, Bancu I, Oliveira-Tercero A, Armengol MP, Menezes-Neto A, Del Portillo HA, et al. Size-exclusion chromatography-based enrichment of extracellular vesicles from urine samples. J Extracell vesicles. 2015;4:27369.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10(3):R25.

Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(3):R25.

Lowry R. Concepts & Applications of inferential statisticsRetrieved March; 2011.

Wang J, Cao Y, Zhang H, Wang T, Tian Q, Lu X, et al. NSDNA: a manually curated database of experimentally supported ncRNAs associated with nervous system diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D902–7.

EV-TRACK Consortium, Van Deun J, Mestdagh P, Agostinis P, Akay Ö, Anand S, et al. EV-TRACK: transparent reporting and centralizing knowledge in extracellular vesicle research. Nat Methods. 2017;14(3):228–32.

Andrés-León E, González Peña D, Gómez-López G, Pisano DG. miRGate: a curated database of human, mouse and rat miRNA-mRNA targets. Database (Oxford). 2015;8:bav035.

Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M, Wyder S, Simonovic M, et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D362–8.

Mi H, Huang X, Muruganujan A, Tang H, Mills C, Kang D, et al. PANTHER version 11: expanded annotation data from gene ontology and reactome pathways, and data analysis tool enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D183–9.

De Menezes-Neto A, Sáez MJ, Lozano-Ramos I, Segui-Barber J, Martin-Jaular L, Ullate JM, et al. Size-exclusion chromatography as a stand-alone methodology identifies novel markers in mass spectrometry analyses of plasma derived vesicles from healthy individuals. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:1–14.

Kim DK, Lee J, Kim SR, et al. EVpedia: a community web portal for extracellular vesicles research. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(6):933–9.

Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, et al. ExoCarta: a web-based compendium of exosomal cargo. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(4):688–92.

Sorensen SS, Nygaard AB, Christensen T. miRNA expression profiles in cerebrospinal fluid and blood of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia – an exploratory study. Transl Neurodegener. 2016;5:6.

Chen L, Yang J, Lü J, Cao S, Zhao Q, Yu Z. Identification of aberrant circulating miRNAs in Parkinson's disease plasma samples. Brain Behav. 2018;8(4):e00941.

Leidinger P, Backes C, Deutscher S, Schmitt K, Mueller SC, Frese K, et al. A blood based 12-miRNA signature of Alzheimer disease patients. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R78.

Satoh J, Kino Y, Niida S. MicroRNA-Seq data analysis pipeline to identify blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease from public data. Biomark Insights. 2015;10:21–31.

Chang WS, Wang YH, Zhu XT, Wu CJ. Genome-wide profiling of miRNA and mRNA expression in Alzheimer's disease. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:2721–31.

Guo R, Fan G, Zhang J, Wu C, Du Y, Ye H, et al. A 9-microRNA signature in serum serves as a noninvasive biomarker in early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60(4):1365–77.

Liguori M, Nuzziello N, Introna A, Consiglio A, Licciulli F, D'Errico E, et al. Dysregulation of MicroRNAs and target genes networks in peripheral blood of patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:288.

Gehrke S, Imai Y, Sokol N, Lu B. Pathogenic LRRK2 negatively regulates microRNA-mediated translational repression. Nature. 2010;466(7306):637–41.

Lau P, Bossers K, Janky R, Salta E, Frigerio CS, Barbash S, et al. Alteration of the microRNA network during the progression of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(10):1613–34.

Cogswell JP, Ward J, Taylor IA. Identification of miRNA changes in Alzheimer’s disease brain and CSF yields putative biomarkers and insights into disease pathways. J Alzh Disease. 2008;14:27–41.

Gwon Y, Kam TI, Kim SH, Song S, Park H, Lim B, et al. TOM1 regulates neuronal accumulation of amyloid-β oligomers by FcγRIIb2 variant in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2018;38(42):9001–18.

Ebrahimkhani S, Vafaee F, Young PE, Hur SSJ, Hawke S, Devenney E, et al. Exosomal microRNA signatures in multiple sclerosis reflect disease status. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14293.

Prabhakar P, Chandra SR, Christopher R. Circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers for the identification of vascular dementia due to cerebral small vessel disease. Age Ageing. 2017;46:861–4.

McKeever PM, Schneider R, Taghdiri F, Weichert A, Multani N, Brown RA, et al. MicroRNA expression levels are altered in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Young-onset Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(12):8826–41.

Galimberti D, Villa C, Fenoglio C, Serpente M, Ghezzi L, Cioffi SM, et al. Circulating miRNAs as potential biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(4):1261–7.

Sanders KA, Benton MC, Lea RA, Maltby VE, Agland S, Griffin N, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals broad down-regulation of microRNAs in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis CD4+ T cells. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8(1):87.

Hara N, Kikuchi M, Miyashita A, Hatsuta H, Saito Y, Kasuga K, et al. Serum microRNA miR-501-3p as a potential biomarker related to the progression of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):10.

Takahashi I, Hama Y, Matsushima M, Hirotani M, Kano T, Hohzen H, et al. Identification of plasma microRNAs as a biomarker of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Brain. 2015;8(1):67.

Leggio L, Vivarelli S, L'Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Caniglia S, Testa N, et al. microRNAs in Parkinson's disease: from pathogenesis to novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2698.

Botta-Orfila T, Morató X, Compta Y, Lozano JJ, Falgàs N, Valldeoriola F, et al. Identification of blood serum micro-RNAs associated with idiopathic and LRRK2 Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92(8):1071–7.

Hoss A. The relationship of microRNAs to clinical features of Huntington's and Parkinson's disease. In: Boston University Theses & Dissertations database; 2016. https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/handle/2144/14604/Hoss_bu_0017E_11703.pdf?sequence=17. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

Kumar S, Vijayan M, Reddy PH. MicroRNA-455-3p as a potential peripheral biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(19):3808–22.

Nagaraj S, Laskowska-Kaszub K, Dębski KJ, Wojsiat J, Dąbrowski M, Gabryelewicz T, et al. Profile of 6 microRNA in blood plasma distinguishes early stage Alzheimer's disease patients from non-demented subjects. Oncotarget. 2017;8(10):16122–43.

Wang WX, Huang Q, Hu Y, Stromberg AJ, Nelson PT. Patterns of microRNA expression in normal and early Alzheimer's disease human temporal cortex: white matter versus gray matter. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121(2):193–205.

Lehmann SM, Krüger C, Park B, Derkow K, Rosenberger K, Baumgart J, et al. An unconventional role for miRNA: let-7 activates toll-like receptor 7 and causes neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(6):827–35.

Vallelunga A, Ragusa M, Di Mauro S, Iannitti T, Pilleri M, Biundo R, et al. Identification of circulating microRNAs for the differential diagnosis of Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:156.

Hu YB, Li CB, Song N, Zou Y, Chen SD, Ren RJ, et al. Diagnostic value of microRNA for Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:13.

Lusardi TA, Phillips JI, Wiedrick JT, Harrington CA, Lind B, Lapidus JA, et al. MicroRNAs in human cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(3):1223–33.

Alexandrov PN, Dua P, Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. MicroRNA (miRNA) speciation in Alzheimer's disease (AD) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and extracellular fluid (ECF). Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:365–73.

Freischmidt A, Müller K, Ludolph AC, Weishaupt JH. Systemic dysregulation of TDP-43 binding microRNAs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:42.

Dong H, Li J, Huang L, Chen X, Li D, Wang T, et al. Serum MicroRNA profiles serve as novel biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:625659.

Martinez B, Peplow PV. MicroRNAs in Parkinson's disease and emerging therapeutic targets. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12(12):1945–59.

Waller R, Goodall EF, Milo M, Cooper-Knock J, Da Costa M, Hobson E, et al. Serum miRNAs miR-206, 143-3p and 374b-5p as potential biomarkers for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neurobiol Aging. 2017;55:123–31.

Dos Santos MCT, Barreto-Sanz MA, Correia BRS, Bell R, Widnall C, Perez LT, et al. miRNA-based signatures in cerebrospinal fluid as potential diagnostic tools for early stage Parkinson's disease. Oncotarget. 2018;9(25):17455–65.

Roser AE, Caldi Gomes L, Halder R, Jain G, Maass F, Tönges L, et al. miR-182-5p and miR-183-5p act as GDNF mimics in dopaminergic midbrain neurons. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;1(11):9–22.

Quek C, Bellingham SA, Jung CH. Defining the purity of exosomes required for diagnostic profiling of small RNA suitable for biomarker discovery. RNA Biol. 2017;14(2):245–58.

Lukiw WJ. Evolution and complexity of micro RNA in the human brain. Front Genet. 2012;3:166.

Savelyeva A, Kuligina EV, Bariakin DN, Kozlov VV, Ryabchikova EI, Richter VA, et al. Variety of RNAs in peripheral blood cells, plasma, and plasma fractions. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7404912.

Castillo-Gonzalez JA, Loera-Arias MJ, Saucedo-Cardenas O, Montes-de-Oca-Luna R, Garcia-Garcia A, Rodriguez-Rocha H. Phosphorylated α-Synuclein-copper complex formation in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2017;2017:9164754.

Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, et al. Alpha-synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:160–4.

Mondragón-Rodríguez S, Perry G, Luna-Muñoz J, Acevedo-Aquino MC, Williams S. Phosphorylation of tau protein at sites Ser 396-404 is one of the earliest events in Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40(2):121–35.

Tian Y, Nan Y, Han L, Zhang A, Wang G, Jia Z, et al. MicroRNA miR-451 downregulates the PI3K/AKT pathway through CAB39 in human glioma. Int J Oncol. 2012;40(4):1105–12.

Heras-Sandoval D, Ávila-Muñoz E, Arias C. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mTor pathway as a therapeutic target for brain aging and neurodegeneration. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4(8):1070–87.

Kuan YH, Gruebl T, Soba P, Eggert S, Nesic I, Back S, et al. PAT1a modulates intracellular transport and processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP), APLP1, and APLP2*. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(52):40114–23.

Golpich M, Amini E, Hemmati F, Ibrahim NM, Rahmani B, Mohamed Z, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) signaling: implications for Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Res. 2015;97:16–26.

Hernandez F, Lucas JJ, Avila J. GSK3 and tau: two convergence points in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl. 1):S141–4.

Hong L, Huang HC, Jiang ZF. Relationship between amyloid-beta and the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Alzheimer's disease. Neurol Res. 2014;36(3):276–82.

Lee HG, Ueda M, Zhu X, Perry G, Smith MA. Ectopic expression of phospho-Smad2 in Alzheimer's disease: uncoupling of the transforming growth factor-beta pathway? J Neurosci Res. 2006;84(8):1856–61.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our profound thanks to Dr. María Yáñez-Mó (Unidad de Investigación, Hospital Sta Cristina, IIS-IP; Departamento Biología Molecular/CBM-SO, UAM) and Dr. Francisco Sánchez-Madrid (Servicio de Inmunología, Hospital Universitario de la Princesa, IIS-IP, UAM; Cell-cell Communication Laboratory, CNIC) for antibodies anti-CD9, anti-CD63 and anti-CD81. The authors especially express gratitude to Marco A. Fernández (Flow Cytometry Unit, IGTP) and Pablo Castro Hartmann (Electron Microscopy Unit, UAB). Also, to Dr. Hernando Del Portillo’s group (ICREA Research Professor at ISGLOBALIGTP) for kindly provide us antibody anti-CD5L. We also thank Anna Oliveira from the Genomics Unit (Health Sciences Research Institute Germans Trias i Pujol), Dr. Mireia Coma from ANAXOMICS Biotech S.L. (Barcelona) and Dr. Sonia Jansa (BioNova científica, S.L.) for their support and guiding for genomic data processing and analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by Spain’s Ministry of Health, project PI18/00276, integrated in the National R + D + I and funded by the ISCIII and the European Regional Development Fund. This work was also supported by the MaratóTV3 grant 201405/10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FBS and KB Conceived and designed the project. AG-V, FBS and KB conceived and decided the experiments, and revised the manuscript. AG-V performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. JC, DV, LI, RR, RA recruited patients and collected samples from patients and healthy controls. RA critically revised the discussion. MPA provided assistance analysing genomic data and discussing the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our institution (Research Institute Germans Trias i Pujol) approved the applied protocol and from each subject, a written informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles in order to use samples and results for publication.

Consent for publication

The manuscript has been read and approved for submission by all authors who contributed to the study. The Ethics Committee also approved the use of the results from human samples for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Purchasing information about miRCURY LNA™ Universal RT microRNA PCR, Pick-&-Mix, Ready-to-use Panels used in the study. (XLSX 53 kb)

Additional file 2:

Raw data from the Next Generation Sequencing experiment for DLB and control samples. (XLSX 84 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gámez-Valero, A., Campdelacreu, J., Vilas, D. et al. Exploratory study on microRNA profiles from plasma-derived extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Neurodegener 8, 31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-019-0169-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-019-0169-5