Abstract

Background

The epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) has undergone dramatic changes, with CTX-M-type enzymes prevailing over other types. blaCTX-M genes, encoding CTX-M-type ESBLs, are usually found on plasmids, but chromosomal location is becoming common. Given that blaCTX-M-harboring strains often exhibit multidrug resistance (MDR), it is important to investigate the association between chromosomally integrated blaCTX-M and the presence of additional antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, and to identify other relevant genetic elements.

Methods

A total of 46 clinical isolates of cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (1 Enterobacter cloacae, 9 Klebsiella pneumoniae, and 36 Escherichia coli) from Zambia were subjected to whole-genome sequencing (WGS) using MiSeq and MinION. By reconstructing nearly complete genomes, blaCTX-M genes were categorized as either chromosomal or plasmid-borne.

Results

WGS-based genotyping identified 58 AMR genes, including four blaCTX-M alleles (i.e., blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-27, and blaCTX-M-55). Hierarchical clustering using selected phenotypic and genotypic characteristics suggested clonal dissemination of blaCTX-M genes. Out of 45 blaCTX-M gene-carrying strains, 7 harbored the gene in their chromosome. In one E. cloacae and three E. coli strains, chromosomal blaCTX-M-15 was located on insertions longer than 10 kb. These insertions were bounded by ISEcp1 at one end, exhibited a high degree of nucleotide sequence homology with previously reported plasmids, and carried multiple AMR genes that corresponded with phenotypic AMR profiles.

Conclusion

Our study revealed the co-occurrence of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 and multiple AMR genes on chromosomal insertions in E. cloacae and E. coli, suggesting that ISEcp1 may be responsible for the transposition of diverse AMR genes from plasmids to chromosomes. Stable retention of such insertions in chromosomes may facilitate the successful propagation of MDR clones among these Enterobacteriaceae species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) are bacterial enzymes capable of degrading most β-lactam antibiotics, rendering them therapeutically useless. Many environmental [1] and animal [2] reservoirs of ESBLs have been reported, however, the heavy use of antimicrobials in hospitals remains the main driver of ESBL-mediated antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [3, 4]. The problem of ESBLs is emerging globally [5, 6] and represents one of the most dire current public health threats in both community and hospital settings [7,8,9]. ESBLs have been identified and described in both industrialized and resource-constrained countries. For example, a high ESBL burden has been observed in France and China, where local hospitals reported prevalence figures of 17.7% [10] and 68.2% [11], respectively. Likewise, studies among hospital patients in Africa show ESBL occurrences as high as 62.3% in Mali [12], 70% in Burkina Faso [13], and 84% in Cote d’Ivoire [14]. In reports from Zambia, ESBL-associated multidrug resistance (MDR) was observed in all 45 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates obtained from neonates [15] and in all 15 diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli isolates from under-five children [16] at the University Teaching Hospital (UTH).

Over 200 ESBLs have been documented [17], of which the majority are derivatives of TEM, SHV, or CTX-M. While TEM and SHV are common ESBL variants, the CTX-M family has recently emerged to become the preponderant type worldwide [18]. This epidemiologic transition has been paralleled by the success and rapid dissemination of the pandemic clone E. coli O25b:H4-ST131, which is frequently associated with blaCTX-M-15 [19]. Additionally, the efficient spread of blaCTX-M genes has also been facilitated by plasmids, integrons, and insertion sequences (IS) (e.g., ISEcp1, IS1, IS5, and IS26) [20]. blaCTX-M genes are usually associated with MDR, since they primarily reside on plasmids carrying other AMR genes. Considering that plasmids often incur a fitness cost in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure [21], it is possible to combat blaCTX-M-associated MDR through the prudent use of antimicrobials. However, a series of studies have reported the occurrence of blaCTX-M genes on the chromosomes of various Enterobacteriaceae [22,23,24,25,26,27], although their placement with other AMR genes was not examined. With a growing number of studies reporting the chromosomal location of blaCTX-M, it is of considerable interest to explore possible links between chromosomally-located blaCTX-M and MDR.

In this study, using phenotypic and genotypic characterization of clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Zambia, we identified the probable clonal spread of blaCTX-M among selected strains. Furthermore, by reconstructing and analyzing nearly complete genome sequences, we identified chromosomally-integrated plasmid segments co-harboring ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 and diverse AMR genes in Enterobacter cloacae and E. coli. Most of the strains harboring these insertions exhibited MDR phenotypes corresponding with the AMR genes in the insertions. Based on these findings, we speculate that ISEcp1-mediated transposition may be responsible for the spread of MDR determinants among Enterobacteriaceae. Furthermore, stable maintenance of these chromosomal insertions may enhance the dissemination of multiple MDR Enterobacteriaceae species, with potentially detrimental effects on patient outcomes.

Methods

Strain selection

Between June and October 2018, 46 non-repetitive cefotaxime resistant clinical Enterobacteriaceae strains were obtained from the UTH, Zambia. These strains were previously isolated from blood (n = 1), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (n = 2), high vaginal swab (HVS) (n = 1), pus (n = 3), sputum (n = 4), stool (n = 30), and urine (n = 5) during routine clinical investigations. Cefotaxime resistance was confirmed by plating each strain on LB agar supplemented with 1 μg/ml cefotaxime (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). In addition, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of cefotaxime against each strain was determined by broth microdilution.

MIC determination

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of strains toward 10 different antimicrobials were determined by broth microdilution using breakpoints specified in Additional file 1: Table S1. Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted 104-fold, added to twofold serial dilutions of antibiotics in a 96-well plate in triplicate, then incubated at 37 °C for 18 h with shaking at 1600 rpm. Next, optical densities at 595 nm (OD595) were measured using the Multiskan FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), with OD595 values of at least 0.1 indicating positive bacterial growth. The MIC was defined as the minimum antibiotic concentration producing an OD595 value of less than 0.1. Two laboratory strains, E. coli MG1655 and E. coli 10-β (NEB, USA), were used for quality control.

Growth rate determination

Bacterial cultures prepared in plain LB were monitored for growth by measuring OD600 in real-time over a period of 16 h. To this end, overnight cultures were diluted 103-fold and added to a 96-well plate in duplicate, then subjected to OD monitoring using the Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 37 °C, while shaking at 600 rpm. Growth rates were estimated from the slopes obtained by fitting parametric models to the resulting data using the R package grofit version 1.1.1 [28].

Whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures prepared in LB supplemented with 1 μg/ml cefotaxime using a QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Kit (QIAGEN). Libraries were prepared using NexteraXT (Illumina) and sequenced using MiSeq (Illumina) to obtain 300 bp paired-reads. The same genomic DNA samples were also subjected to long-read sequencing by MinION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) using a Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK004) and an R9.5 flowcell (FLO-MIN107). Short-read trimming and adapter sequence removal were performed using Trim Galore version 0.4.2 with options of "–paired –nextera" (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore). Basecalling of long reads was performed using Guppy Basecalling Software version 3.4.5 and the reads were assembled using Canu version 1.8 [29] with the "corOutCoverage = 1000 genomeSize = 6 m" option applied. Redundant repeats at terminal ends of contigs were identified using Gepard version 1.40 [30] and manually trimmed down to one copy. Trimmed contigs were then subjected to base-error correction with Illumina reads using Pilon version 1.23 [31]. Contigs longer than 2 Mb were classified as chromosomal while circular contigs of less than 500 kb and containing plasmid replicons were classified as plasmids. To categorize the rest of the contigs as either chromosomal or plasmid-based in origin, a local database was generated for each strain using known chromosomal and plasmid segments. Unclassified contigs were then subjected to BLASTn searches against the local database and sequences matching known chromosome or plasmid regions with at least 70% identity were regarded as redundant and removed from the data pool. Sequences exhibiting hits with less than 70% identity were retained and subjected to NCBI BLASTn searches against the nt database. A sequence was regarded as chromosomal if at least 70% of the top 10 hits were chromosomes, and as plasmid-based if at least 70% of the top 10 hits were plasmids.

Phylogenetic analysis

To elucidate the evolutionary relationships among strains, whole genome-based phylogenetic trees were constructed using Parsnp version 1.2 [32] and imported into MEGA version 7.0 [33] for visualization and editing. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed in silico by uploading raw Illumina reads to a public MLST server (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST) [34].

Detection of plasmid replicons, strain serotypes, and AMR genes

Plasmid replicons and O:H serotypes were determined by interrogating contigs with PlasmidFinder [35] and EcOH [36] databases, respectively, using ABRicate software version 0.8.10 (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate) with options –mincov 90 and –minid 90 specified. To identify AMR genes, the AMRFinderPlus tool [37] was used with option -i 0.7 engaged.

Determination of clustering patterns among strains

To unravel the mechanisms of blaCTX-M spread at the UTH, strains were compared in terms of AMR phenotype, AMR genes, and plasmid replicons by exploiting clustering patterns and correlations using the R package ComplexHeatmap [38].

Sequence alignment and determination of chromosomal insertion locations of bla CTX-M

Strains carrying chromosomal blaCTX-M were annotated using DFAST version 1.2.4 [39] and aligned to reference sequences using Mauve [40]. Zam_UTH_18, Zam_UTH_26, and Zam_UTH_41 were aligned against the reference strain E. coli MG1655 (GenBank accession no. NC_000913.2), while Zam_UTH_44 was aligned against E. cloacae ATCC 13047 (GenBank accession no. NC_014121.1). Zam_UTH_42 and Zam_UTH_47 were aligned against E. coli ST648 (GenBank accession no. CP008697.1), while Zam_UTH_43 was aligned against another strain (Zam_UTH_08) in our data. Comparison, visualization, and exploration of the data were performed using genoPlotR [41].

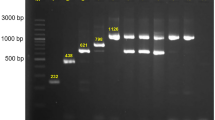

PCR and sanger sequencing

To validate and further characterize chromosomal insertions, junctions between chromosomes and plasmids were amplified by PCR using primers shown in Supplementary Additional file 1: Table S2. Where possible, primers external to the insertion were used and amplicon size was compared to that obtained from a control strain. Also, strains for which the exact blaCTX-M allele was unidentifiable due to low Illumina read number were subjected to PCR using primers shown in Additional file 1: Table S3, followed by Sanger sequencing. Briefly, PCR was performed using KOD One Master Mix (TOYOBO, Japan) and the products were purified using a MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). Sequencing PCR was performed using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), followed by Sanger sequencing using a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA). Raw sequence data was assembled using SnapGene software (Insightful Science, available at snapgene.com) and the obtained consensus sequences analyzed by the AMRFinderPlus tool [37] with option -i 0.7.

Results

MLST revealed high genetic diversity among strains

This study examined 46 cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains isolated from various clinical samples among patients at the UTH, Zambia (Table 1). To elucidate the genetic variability and relationships among these strains, WGS was used to reconstruct nearly complete genome sequences. In silico MLST from the WGS data identified the strains as E. cloacae (1/46, 2.2%), K. pneumoniae (9/46, 19.6%), and E. coli (36/46, 78.3%) (Table 1).

Although E. coli were represented by 12 sequence types (STs), 25/36 (69.4%) strains belonged to 4 STs (i.e., ST69, ST131, ST617, and ST405) (Fig. 1a), suggesting the expansion of a few eminent clones. ST131 is known to rapidly spread due to its diverse virulence and AMR mechanisms [42], but its prevalence in this study, at 6/36 (16.7%), was second to that of ST69. ST69 predominated, with a prevalence of 9/36 (25.0%), highlighting its important contribution to the burden of ESBLs in the local hospital. Of the 12 E. coli STs identified in this study, one was novel and has since been designated ST11176. Among the K. pneumoniae isolates, which were classified into 3 STs, the most prevalent was ST307, representing 6/9 (66.7%) strains (Fig. 1b).

Phylogenetic analysis. Whole genome-based phylogenetic trees for 36 E. coli and 9 K. pneumoniae strains. a E. coli: a total of 12 STs were identified, including one novel type (marked with *). Four STs constituted 25/36 (69.4%) of E. coli strains, the most common being ST69 (9 strains), followed by ST131 (6 strains). b K. pneumoniae: a total of 3 STs were identified, with ST307 alone representing 6/9 (66.7%) strains

Chromosomal bla CTX-M genes were identified by in silico analysis

To identify AMR gene patterns among the strains, in silico detection was performed using AMR gene sequence databases. A total of 58 AMR genes belonging to 12 classes were identified (Additional file 1: Table S4). Among the β-lactamase genes, the blaCTX-M family predominated, with 45/46 (97.8%) strains carrying at least one of the following alleles: blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-27, and blaCTX-M-55 (Fig. 2). These blaCTX-M genes were located on chromosomes in 7 strains (7/45, 15.6%; one E. cloacae and six E. coli); one of these strains harbored an extra blaCTX-M gene on a plasmid, and the remaining 38 strains (38/45, 84.4%) harbored blaCTX-M genes exclusively on plasmids. In agreement with previous studies [43], blaCTX-M-15 was the most prevalent ESBL gene (28/45, 62.2%). Despite documentation of a close association between blaCTX-M-15 gene and E. coli ST131 [44], only one E. coli ST131 (1/6, 16.7%) possessed blaCTX-M-15 (Fig. 2), with the remaining five E. coli ST131 strains possessing plasmid-borne blaCTX-M-27. In silico serotyping of all six E. coli ST131 strains revealed that none of them belonged to the pandemic clone O25b:H4-ST131, with the 5 blaCTX-M-27-carrying strains belonging to Onovel31:H4 and the blaCTX-M-15-carrying strain belonging to O107:H5.

AMR phenotypes, AMR genes and plasmid replicons. All but one strain displayed resistance to at least three antimicrobial classes. There was no phenotypic or genotypic resistance to imipenem, however, one strain (Zam_UTH_40) exhibited phenotypic resistance to colistin. A total of 12 AMR gene classes were identified. Within the β-lactamase gene class, the blaCTX-M family showed the most diversity, with blaCTX-M-15 being the most common variant. Most blaCTX-M genes were located on plasmids, however, 7/45 (15.6%) strains harbored the genes on the chromosome. A total of 24 plasmid replicons were detected, with the most prevalent being IncFIB(AP001918)_1, which was present in 30/46 (65.2%) strains. Hierarchical clustering showed aggregation of strains of the same ST. Cefotaxime (CTX) is not shown here since all strains were selected using CTX. AMP; ampicillin. CHL; chloramphenicol. CIP; ciprofloxacin. CST; colistin. DOX; doxycycline. GEN; gentamicin. IPM; imipenem. NAL; nalidixic acid. NIT; nitrofurantoin

To determine antimicrobial susceptibility profiles, MICs of 10 antimicrobials were measured against each strain. Forty-five out of 46 (97.8%) strains displayed MDR phenotypes, defined as a lack of susceptibility to at least one antimicrobial from at least three antimicrobial classes [45]. The highest non-susceptibility rate was to ampicillin (46/46, 100%), followed by gentamicin (43/46, 93.5%), ciprofloxacin (41/46, 89.1%), and nalidixic acid (41/46, 89.1%). While no carbapenem resistance was detected, one K. pneumoniae strain (1/46, 2.2%) displayed low-level resistance (MIC = 4 μg/ml) to the drug of last resort, colistin (Fig. 2). In almost all cases the probability of phenotypic resistance was high (positive predictive value ≥ 80%) given a positive genotypic result (Additional file 1: Table S5). While previous studies have shown a significant correlation between resistance range and fitness cost [46], we did not find any correlation between the number of AMR genes and bacterial growth rate (Additional file 1: Fig. S1A).

E. coli ST69 strains possess an IncH plasmid harboring bla CTX-M-14

To characterize the plasmid content of the strains, WGS data were compared against the PlasmidFinder database [35]. In total, 24 plasmid replicons were detected, the most common being IncFIB(AP001918)_1 (30/46, 65.2%), IncFIA_1 (27/46, 58.7%), Col(MG828)_1 (16/46, 34.8%), and IncB/O/K/Z_2 (13/46, 28.3%) (Fig. 2). Most E. coli ST69 strains (8/9, 88.0%) in this study carried an IncF plasmid possessing dfrA12 and sul2 genes, encoding resistance to trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole, respectively. This was expected since previous studies have associated E. coli ST69 with IncF plasmids encoding trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) resistance [47]. However, all the E. coli ST69 strains in this study also carried two additional MDR plasmids, including a 225 kb IncH plasmid which is not commonly found in this ST [47, 48]. This IncH plasmid contained blaCTX-M-14 and shared over 80% homology with an IncH plasmid in a K. pneumoniae ST37 strain (Zam_UTH_04) from our data pool (Additional file 1: Fig. S2A), indicating that these plasmids could share a common origin. The two plasmids exhibited similar genetic contexts around blaCTX-M-14 gene, however, both plasmids contained several insertions that carried various AMR genes as well as genes related to fitness traits (Additional file 1: Fig. S2B). For instance, the IncH plasmid from E. coli ST69 possessed the mucAB operon which is associated with resistance to DNA-damaging agents such as ultraviolet radiation [49]. Furthermore, this plasmid also harbored the mer operon that is involved in resistance to organomercury compounds [50].

Analysis of the other three dominant E. coli STs (i.e., ST131, ST617, and ST405) showed a close association between IncF plasmids and blaCTX-M genes, as previously reported [51]. However, comparison of IncF plasmids from strains of different STs revealed low nucleotide sequence homology (Additional file 1: Fig. S2C), ruling out horizontal gene transfer as a mode of blaCTX-M gene propagation.

The spread of bla CTX-M genes is driven by clonal expansion

To establish the mode of blaCTX-M propagation among strains, hierarchical clustering was conducted using AMR phenotypes, AMR genes, and plasmid replicons as variables. The results indicated that strains can be grouped into 4 main clusters, which we designated as EC1, EC2, EC3, and KP (Fig. 2). The largest cluster, EC1, was predominated by E. coli ST69 and was characterized by the presence of blaCTX-M-14 and IncHI. In addition, EC1 contained more AMR genes than what was observed in clusters EC2, EC3, and KP (P < 0.01) (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Cluster EC2 was closely related to EC3, with both clusters containing qacEdelta1, mph(A), and aad5 genes that were absent in clusters EC1 and KP. Lastly, cluster KP, formed by K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae, was defined by the presence of four plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes, oqxA, oqxB, oqxB19, and qnrB1. Overall, the analysis showed the aggregation of strains belonging to the same ST. Taken together with our MLST findings, these results suggest the possible spread of blaCTX-M by clonal expansion rather than horizontal gene transfer.

Large chromosomal insertions co-harbor bla CTX-M-15 and other AMR genes

To determine the genetic contexts of chromosomally-located blaCTX-M in 7 strains (one E. cloacae and six E. coli), chromosomal insertions were identified by alignment against reference sequences using Mauve [40]. In all cases, the insertions were bounded by ISEcp1 at one end (Figs. 3, 4, 5), implying that this element is responsible for mobilization. However, some insertions also harbored various IS elements (e.g., IS1, IS6) and transposons, suggesting that other sophisticated mechanisms may play a role. The inserted segments, which were confirmed by PCR (Additional file 1: Fig. S4), were genetically distinct, with sizes ranging from ~ 3 kb to ~ 41 kb. Furthermore, these insertions showed high nucleotide sequence similarity to plasmids available in the NCBI GenBank, implying the transposition from plasmid to chromosome. In one E. cloacae and three E. coli strains, blaCTX-M-carrying insertions were larger than 10 kb and harbored other types of AMR genes. As expected, strains possessing these MDR insertions showed resistance to multiple antibiotics of clinical importance (Figs. 4, 5).

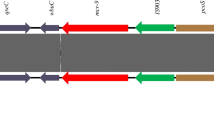

blaCTX-M genes present on short chromosomal insertions in E. coli. a Zam_UTH_41. This E. coli ST8767 strain carried blaCTX-M-14 on a 3,095 bp chromosomal insertion with ISEcp1 located 249 bp upstream of blaCTX-M-14. Zam_UTH_26 (not shown) also had a similar genetic context for its insertion. b Zam_UTH_43. This E. coli ST131 O107:H5 strain harbored blaCTX-M-15 on a 6,036 bp chromosomal insertion, with ISEcp1 located 255 bp upstream of blaCTX-M-15. About 2.5 kb downstream of this insertion was another insertion that harbored genes conferring resistance to chloramphenicol (cat), β-lactams (blaOXA-1), and aminoglycosides/quinolones (aac(6′)-Ib-cr5). F1, F2, F3, R1, R2, R3; primers used for confirmation of insertions

blaCTX-M genes present on large chromosomal insertions in E. coli. a Zam_UTH_18. This E. coli ST3580 strain possessed blaCTX-M-15 on an 11,383 bp chromosomal insertion, which was very similar to plasmid pF609 (GenBank accession no. MK965545.1). blaCTX-M-15 was closely associated with ISEcp1, which was located 255 bp upstream. The insertion also harbored the quinolone resistance gene qnrS1, located 4639 bp downstream of blaCTX-M-15. The phenotypic AMR profile of this strain showed resistance to ampicillin and susceptibility to quinolones. b Zam_UTH_42. This E. coli ST648 strain harbored blaCTX-M-15 on a 14,328 bp chromosomal insertion that was very similar to plasmid p13ARS_MMH0112-2 (GenBank accession no. LR697123.1). This insertion carried genes associated with resistance to aminoglycosides (aac(3)-IIa), aminoglycosides/quinolones (aac(6′)-Ib-cr5), β-lactams (blaOXA-1, blaTEM-1), and chloramphenicol (catB3). ISEcp1 was located 255 bp upstream of blaCTX-M-15, however, unlike in other strains, ISEcp1 in this strain was truncated by IS1 and transposase. The phenotypic AMR profile of this strain was consistent with the AMR genotype for the insertion. Zam_UTH_47 (not shown) also had a similar genetic context for its insertion. F4, F5, F6, F7, R4, R5, R6, R7; primers used for confirmation of insertions. White; susceptible. Black; resistance phenotype in the absence of corresponding AMR gene. Red; β-lactam resistance. Brown; chloramphenicol resistance. Green; aminoglycoside and/or quinolone resistance

blaCTX-M gene on a large chromosomal insertion in E. cloacae. Zam_UTH_44. This E. cloacae ST316 strain carried blaCTX-M-15 on a ~ 41 kb chromosomal insertion that exhibited nucleotide sequence homology with plasmid pCRENT-193_1 (GenBank accession no. CP024813.1). ISEcp1 was located 255 bp upstream of blaCTX-M-15. The insertion also included diverse AMR genes encoding resistance to six antimicrobial classes, namely; aminoglycosides (aac(3)-IIa), quinolones (qnrB1), aminoglycosides/quinolones (aac(6′)-Ib-cr5), β-lactams (blaOXA-1), trimethoprim (dfrA14), chloramphenicol (catB3), and tetracyclines (tet(A)). The phenotypic AMR profile of this strain was consistent with the AMR genotype of the insertion. F8, F9, R8, R9; primers used for confirmation of insertions. White; susceptible. Black; resistance phenotype in the absence of corresponding AMR gene. Red; β-lactam resistance. Brown; chloramphenicol resistance. Green; aminoglycoside and/or quinolone resistance. Pink; tetracycline resistance

Chromosomal insertions were bracketed by 5-bp direct repeats in all six E. coli strains, which is typical of ISEcp1-mediated transposition. However, ISEcp1 was truncated by IS1 and transposase in two strains (Zam_UTH_42 and Zam_UTH_47) (Fig. 4b), suggesting that the interrupted ISEcp1 may no longer be functional, and that mobilization of blaCTX-M-15 may have been induced by IS1 and/or transposase. In all strains, the relative position of the downstream blaCTX-M gene was constant for each allele (i.e., blaCTX-M-14 or blaCTX-M-15), indicating possible allele-specific ancestral origins. For instance, in Zam_UTH_26 and Zam_UTH_41 (both E. coli ST8767), blaCTX-M-14 was located 249 bp downstream of ISEcp1 on a 3,095 bp insertion. Similarly, in 5 strains, blaCTX-M-15 was observed 255 bp downstream of ISEcp1 on insertions of varying lengths. More specifically, Zam_UTH_43 (E. coli ST131) (Fig. 3b) and Zam_UTH_18 (E. coli ST3580) (Fig. 4a) carried blaCTX-M-15 on 6,036 bp and 11,383 bp insertions, respectively, while Zam_UTH_42 and Zam_UTH_47 (both E. coli ST648) (Fig. 4b) carried blaCTX-M-15 on a 14,328 bp insertion. Furthermore, Zam_UTH_44 (E. cloacae ST316) (Fig. 5) carried blaCTX-M-15 on a chromosomal insertion longer than 41 kb.

Of the 7 strains carrying chromosomal blaCTX-M, 4 strains (i.e., Zam_UTH_18, Zam_UTH_42, Zam_UTH_44, and Zam_UTH_47) harbored the gene on insertions longer than 10 kb that exhibited high nucleotide sequence similarity to plasmids available in the NCBI GenBank (Figs. 3, 4, 5). Notably, the insertion in Zam_UTH_18 also appeared in the chromosome sequences of Salmonella enterica (GenBank accession no. CP045038) and two E. coli ST38 strains (GenBank accession no. CP010116 and CP018976). Furthermore, on the 4 insertions larger than 10 kb, we found additional AMR genes downstream of blaCTX-M-15. Zam_UTH_18 was found to possess the qnrS1 gene, which is associated with quinolone resistance, while Zam_UTH_42 and Zam_UTH_47 had genes associated with resistance to aminoglycosides (aac(3)-IIa), aminoglycosides/quinolones (aac(6′)-Ib-cr5), β-lactams (blaOXA-1, blaTEM-1), and chloramphenicol (catB3). Similarly, Zam_UTH_44 possessed 7 genes known to confer resistance to aminoglycosides (aac(3)-IIa), quinolones (qnrB1), aminoglycosides/quinolones (aac(6′)-Ib-cr5), β-lactams (blaOXA-1), trimethoprim (dfrA14), chloramphenicol (catB3), and tetracyclines (tet(A)).

Phenotypic AMR profiles of the strains carrying chromosomal blaCTX-M were in agreement with the presence of AMR genes on insertions except for Zam_UTH_18 which showed quinolone susceptibility despite possessing qnrS1. Additionally, these strains had cefotaxime MICs that were at least 64-fold higher than the clinical breakpoint of 2 μg/ml published by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [52]. Though Zam_UTH_26 was closely related to Zam_UTH_41 (Fig. 1a), the latter had a higher cefotaxime MIC (≥ twofold) possibly due to the presence of plasmid-borne blaCTX-M-15, in addition to blaCTX-M-14 on the chromosome. This difference was also reflected by the lower growth rate (μ = 0.136) of Zam_UTH_41 compared to Zam_UTH_26 (μ = 0.189), suggesting a fitness cost imposed by the extra blaCTX-M-15-carrying plasmid. Likewise, Zam_UTH_18, which lacked plasmids, grew at a rate higher than the 75th percentile of the estimated E. coli growth rates (Additional file 1: Fig. S1B; Additional file 2: Fig. S5).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to investigate the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of clinical Enterobacteriaceae strains from the UTH, Zambia. Our results suggest that the dissemination of blaCTX-M has been mediated mainly by clonal expansion. While the majority of strains possessed blaCTX-M genes on plasmids, 7 strains harbored the genes on chromosomes. Data obtained in previous studies indicate that the chromosomal incorporation of blaCTX-M is usually mediated by ISEcp1; however, the co-occurrence of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M and additional AMR genes has never been reported in E. cloacae or E. coli. Despite approaches enabling examination of the immediate flanking regions of chromosomal blaCTX-M, limitations of Southern hybridization and WGS using short reads make it difficult to identify and resolve large chromosomal insertions. By reconstructing nearly complete genomes, our analysis of the genetic context of chromosomally-located blaCTX-M was significantly improved compared to previous analyses. In one E. cloacae and three E. coli strains, we found blaCTX-M-15 in large chromosomal insertions whose nucleotide sequences significantly resembled plasmids available in the NCBI GenBank. We also found that these insertions were bounded by ISEcp1 at one end and possessed additional AMR genes. Phenotypic AMR profiles of these strains showed near-perfect agreement with the observed chromosomal MDR genotypes. These findings suggest that ISEcp1 contributes to the dissemination of blaCTX-M-15-associated MDR determinants among various Enterobacteriaceae species.

Phylogenetic analysis highlighted the predominance of four E. coli STs (ST69, ST131, ST617, and ST405) and one K. pneumoniae ST (ST307), suggesting the clonal dissemination of a few particular strains. Fitting with this hypothesis, strain comparisons based on AMR phenotypes, AMR genes, and plasmid replicons generally showed clustering of strains according to ST. Most E. coli ST131 strains belong to the O25b:H4 pandemic clone which frequently harbors blaCTX-M-15 [42, 53]. However, the six E. coli ST131 strains examined in this study belonged to either Onovel31:H4 or O107:H5. Newer variants of E. coli ST131 have recently emerged [54], including Onovel31:H4 [55] detected in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first report of E. coli ST131 with serotype O107:H5.

The most abundant E. coli ST in this study, ST69, belonged to a clade that possessed more AMR genes compared to other clades (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Generally, ST69 strains lack ESBL genes [56], are associated with community acquired infections [57], and carry IncF plasmids encoding SXT resistance [47]. Interestingly, the ST69 strains in this study carried blaCTX-M-14 on an IncH plasmid and showed the highest prevalence among the examined hospital isolates. This rare combination of IncH plasmids and E. coli ST69 was also reported in an Egyptian strain isolated from raw milk cheese [58], although the IncH plasmid (GenBank accession no. CP023143) in this strain was substantially different in AMR gene content. The observed predominance of ST69 in our study may be a consequence of selection pressure arising from the use of SXT for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP). In Zambia, HIV infected or exposed patients at risk of developing PCP receive SXT prophylaxis for several months, or even years, until they are no longer at risk [59]. While SXT prophylaxis is highly beneficial, this practice has been associated with the development of SXT resistance in various bacterial species, including E. coli [60,61,62]. We speculate that the high proportion of ST69 observed here was a result of SXT-mediated selection, followed by acquisition of the blaCTX-M-14-containing IncH plasmid. The resulting ESBL phenotype, coupled with survival mechanisms such as error-prone mutagenesis mediated by mucAB operon, probably fostered the emergence of ST69 as a successful hospital clone.

The phenotypic and genotypic resistance observed in this study may be attributed to poor local antimicrobial stewardship. In Zambia, policies promoting the judicious use of antimicrobials are hardly adhered to and most drugs can be accessed without a prescription [63]. Moreover, a study conducted at the UTH reported a 53.7% antibiotic prescription rate [64], clearly surpassing the 30% rate recommended by the WHO [65]. Most serious bacterial infections among UTH inpatients are treated with third-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cefotaxime) [66], while quinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin) are commonly used for outpatient infections [64]. Our results show that nearly 90% of cefotaxime-resistant strains were also resistant to quinolones. Meanwhile, carbapenem use at UTH is strictly monitored and prescription usually depends on robust laboratory evidence. Encouragingly, we did not detect carbapenem resistance either phenotypically or genotypically. However, it is noteworthy that carbapenem resistance has continued to emerge globally, even in Africa [67], resulting in the gradual re-introduction of colistin as a drug of last resort [68]. Despite this transition in treatment by many countries, there is no current report of the clinical use of colistin in Zambia. Nonetheless, we found borderline phenotypic colistin resistance in a K. pneumoniae strain (Zam_UTH_40) isolated from CSF. While this finding is of clinical significance, further studies are needed to verify this observation.

Systematic characterization of the diverse genetic environments of chromosomally-located blaCTX-M revealed a close association with ISEcp1, as previously reported [69]. Intriguingly, one E. cloacae and three E. coli strains carried both ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 and other AMR genes on large chromosomal insertions that significantly resembled publicly available plasmid sequences. While this work was in progress, Goswami et al. described an E. coli strain possessing blaCTX-M-15 and four other AMR genes on a chromosomal insertion similar to a plasmid region, however, in contrast to our work, the mobilizing unit was IS26 [47]. More recently, in South Korea, Yoon et al. observed the co-occurrence of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 and other AMR genes on chromosomal insertions in K. pneumoniae [70]. In contrast, none of the K. pneumoniae strains in our study harbored chromosomal blaCTX-M genes, probably due to geographic variations between Zambia and South Korea. Here we report, for the first time, chromosomal integration of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15-associated MDR elements in E. cloacae and E. coli. Since the identified MDR insertions were all bounded by ISEcp1 at one end, it is likely that this IS element was responsible for mobilization. However, the presence of other mobile elements, as well as the interruption of ISEcp1 in 2 strains, also potentially suggests the occurrence of other complex genetic events. Phenotypic susceptibilities confirmed that chromosomally-located MDR determinants were capable of conferring AMR to multiple drugs. For instance, Zam_UTH_44, which carried exclusively chromosomal AMR genes, displayed resistance to β-lactams, quinolones, gentamicin and chloramphenicol. However, Zam_UTH_18 was susceptible to quinolones despite harboring chromosomal qnrS1. We did not investigate qnrS1 expression, however, this observed contradiction could be due to the fact that PMQR determinants (such as qnrS1) are associated with only small reductions in quinolone susceptibility [71]. Nevertheless, such small changes are usually sufficient to cause treatment failure in patients, and thus some researchers advocate for the revision of quinolone breakpoints [72].

While the benefits of chromosomal integration of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15-associated MDR elements are not fully understood, it may help accelerate the spread of MDR determinants as an intermediary reservoir. As previously observed, plasmids belonging to the same incompatibility group are unable to stably coexist in the same bacterial host cell line [73]. Interplasmid gene transfer would thus be optimized by transient chromosomal incorporation. Furthermore, chromosomal integration of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15-associated MDR elements warrants stable dissemination of resistant strains regardless of the presence or absence of antibiotic selection pressure [70]. Since bacteria are likely to lose plasmids when the cost of maintaining them outweighs their benefits [74, 75], chromosomal integration and the stable maintenance of crucial AMR genes seem to be a viable safeguard for survival and continued AMR spread. This hypothesis is supported by our observation that Zam_UTH_18 did not carry any plasmids but possessed a chromosomally-incorporated 11 kb segment bearing blaCTX-M-15 and qnrS1. The high growth rate exhibited by this strain may suggest a fitness advantage conferred by its plasmid-free status. We speculate that Zam_UTH_18 may have possessed a plasmid that was lost after chromosomal integration of the blaCTX-M-15-carrying segment. To verify this observation, more studies need to be conducted on growth and competitive performance using a reference strain harboring the blaCTX-M-15-containing segment on a plasmid.

Conclusion

We characterized AMR phenotypes and genotypes of cefotaxime-resistant clinical Enterobacteriaceae and noted that the main mode of blaCTX-M transmission was through the spread of clones of a few resilient STs. In one E. cloacae and three E. coli strains, chromosomally-integrated ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 transposition unit existed on large insertions that concurrently harbored diverse AMR genes and originated from plasmids. Our findings suggest that ISEcp1 facilitates chromosomal integration of blaCTX-M-15-associated MDR determinants in diverse Enterobacteriaceae species. Stable maintenance of these determinants on chromosomes may promote the propagation of MDR clones among multiple Enterobacteriaceae species, jeopardizing the treatment efficacy of available antimicrobials.

Availability of data and materials

All raw reads have been deposited in the DDBJ under the DRA accession number, DRA010721. The nearly complete genome sequences have been deposited in the GenBank under the BioProject identifier PRJDB10450. Individual accession numbers for each strain are provided in Table 2.

References

Hendriksen RS, Munk P, Njage P, van Bunnik B, McNally L, Lukjancenko O, Röder T, Nieuwenhuijse D, Pedersen SK, Kjeldgaard J, et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1124.

Carattoli A. Animal reservoirs for extended spectrum beta-lactamase producers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(Suppl 1):117–23.

Zerr DM, Miles-Jay A, Kronman MP, Zhou C, Adler AL, Haaland W, Weissman SJ, Elward A, Newland JG, Zaoutis T, Qin X. Previous antibiotic exposure increases risk of infection with extended-spectrum-β-Lactamase- and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Pediatric Patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:4237–43.

Demirdag K, Hosoglu S. Epidemiology and risk factors for ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: a case control study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:717–22.

Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2145–55.

Hernández J, Stedt J, Bonnedahl J, Molin Y, Drobni M, Calisto-Ulloa N, Gomez-Fuentes C, Astorga-España MS, González-Acuña D, Waldenström J, et al. Human-associated extended-spectrum β-lactamase in the Antarctic. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2056–8.

Irek EO, Amupitan AA, Obadare TO, Aboderin AO. A systematic review of healthcare-associated infections in Africa: an antimicrobial resistance perspective. Afr J Lab Med. 2018;7:796.

Ben-Ami R, Rodríguez-Baño J, Arslan H, Pitout JD, Quentin C, Calbo ES, Azap OK, Arpin C, Pascual A, Livermore DM, et al. A multinational survey of risk factors for infection with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in nonhospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:682–90.

Flokas ME, Karanika S, Alevizakos M, Mylonakis E. Prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in pediatric bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171216.

Pilmis B, Cattoir V, Lecointe D, Limelette A, Grall I, Mizrahi A, Marcade G, Poilane I, Guillard T, Bourgeois Nicolaos N, et al. Carriage of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in French hospitals: the PORTABLSE study. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98:247–52.

Liu H, Wang Y, Wang G, Xing Q, Shao L, Dong X, Sai L, Liu Y, Ma L. The prevalence of Escherichia coli strains with extended spectrum beta-lactamases isolated in China. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:335.

Sangare SA, Rondinaud E, Maataoui N, Maiga AI, Guindo I, Maiga A, Camara N, Dicko OA, Dao S, Diallo S, et al. Very high prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in bacteriemic patients hospitalized in teaching hospitals in Bamako, Mali. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172652.

Ouedraogo AS, Sanou M, Kissou A, Sanou S, Solaré H, Kaboré F, Poda A, Aberkane S, Bouzinbi N, Sano I, et al. High prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae among clinical isolates in Burkina Faso. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:326.

Müller-Schulte E, Tuo MN, Akoua-Koffi C, Schaumburg F, Becker SL. High prevalence of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in clinical samples from central Côte d’Ivoire. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:207–9.

Mumbula EM, Kwenda G, Samutela MT, Kalonda A, Mwansa JCL, Mwenya D, Koryolova L, Kaile T, Marimo CC, Lukwesa-Musyani C. Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. J Med Sci Technol. 2015;4:85–91.

Chiyangi H, Muma JB, Malama S, Manyahi J, Abade A, Kwenda G, Matee MI. Identification and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacterial enteropathogens from children aged 0–59 months at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia: a prospective cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:117.

Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86.

Woerther PL, Burdet C, Chachaty E, Andremont A. Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:744–58.

Lau SH, Kaufmann ME, Livermore DM, Woodford N, Willshaw GA, Cheasty T, Stamper K, Reddy S, Cheesbrough J, Bolton FJ, et al. UK epidemic Escherichia coli strains A-E, with CTX-M-15 beta-lactamase, all belong to the international O25:H4-ST131 clone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1241–4.

Zhao WH, Hu ZQ. Epidemiology and genetics of CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Gram-negative bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2013;39:79–101.

San Millan A, MacLean RC: Fitness Costs of Plasmids: a Limit to Plasmid Transmission. Microbiol Spectr 2017, 5.

Wu C, Lin C, Zhu X, Liu H, Zhou W, Lu J, Zhu L, Bao Q, Cheng C, Hu Y. The β-lactamase gene profile and a plasmid-carrying multiple heavy metal resistance genes of enterobacter cloacae. Int J Genomics. 2018;2018:4989602.

Rodríguez I, Thomas K, Van Essen A, Schink AK, Day M, Chattaway M, Wu G, Mevius D, Helmuth R, Guerra B. Chromosomal location of blaCTX-M genes in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Germany, The Netherlands and the UK. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43:553–7.

van Aartsen JJ, Moore CE, Parry CM, Turner P, Phot N, Mao S, Suy K, Davies T, Giess A, Sheppard AE, et al. Epidemiology of paediatric gastrointestinal colonisation by extended spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in north-west Cambodia. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:59.

Mshana SE, Fritzenwanker M, Falgenhauer L, Domann E, Hain T, Chakraborty T, Imirzalioglu C. Molecular epidemiology and characterization of an outbreak causing Klebsiella pneumoniae clone carrying chromosomally located blaCTX-M-15 at a German University-Hospital. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:122.

Fabre L, Delauné A, Espié E, Nygard K, Pardos M, Polomack L, Guesnier F, Galimand M, Lassen J, Weill F-X. Chromosomal integration of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene blaCTX-M-15 in Salmonella enterica serotype concord isolates from internationally adopted children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1808;2009:53.

Harada S, Ishii Y, Saga T, Kouyama Y, Tateda K, Yamaguchi K. Chromosomal integration and location on IncT plasmids of the blaCTX-M-2 gene in Proteus mirabilis clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1093–6.

Kahm M, Hasenbrink G, Lichtenberg-Fraté H, Ludwig J, Kschischo M: grofit: Fitting Biological Growth Curves with R. Journal of Statistical Software; Vol 1, Issue 7 (2010) 2010.

Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–36.

Krumsiek J, Arnold R, Rattei T. Gepard: a rapid and sensitive tool for creating dotplots on genome scale. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1026–8.

Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, Cuomo CA, Zeng Q, Wortman J, Young SK, Earl AM. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112963.

Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1355–61.

Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Møller Aarestrup F, Hasman H. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–903.

Ingle DJ, Valcanis M, Kuzevski A, Tauschek M, Inouye M, Stinear T, Levine MM, Robins-Browne RM, Holt KE: In silico serotyping of E. coli from short read data identifies limited novel O-loci but extensive diversity of O:H serotype combinations within and between pathogenic lineages. Microb Genom 2016, 2:e000064.

Feldgarden M, Brover V, Haft DH, Prasad AB, Slotta DJ, Tolstoy I, Tyson GH, Zhao S, Hsu CH, McDermott PF, et al: Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63.

Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2847–9.

Tanizawa Y, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y. DFAST: a flexible prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline for faster genome publication. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1037–9.

Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–403.

Guy L, Kultima JR, Andersson SG. genoPlotR: comparative gene and genome visualization in R. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2334–5.

Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1–14.

Ouchar Mahamat O, Tidjani A, Lounnas M, Hide M, Benavides J, Somasse C, Ouedraogo AS, Sanou S, Carrière C, Bañuls AL, et al. Fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in hospital and community settings in Chad. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:169.

Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Caniça MM, Park YJ, Lavigne JP, Pitout J, Johnson JR. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:273–81.

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81.

Vogwill T, MacLean RC. The genetic basis of the fitness costs of antimicrobial resistance: a meta-analysis approach. Evol Appl. 2015;8:284–95.

Goswami C, Fox S, Holden MTG, Connor M, Leanord A, Evans TJ: Origin, maintenance and spread of antibiotic resistance genes within plasmids and chromosomes of bloodstream isolates of Escherichia coli. Microb Genom 2020, 6.

Day MJ, Rodríguez I, van Essen-Zandbergen A, Dierikx C, Kadlec K, Schink AK, Wu G, Chattaway MA, DoNascimento V, Wain J, et al. Diversity of STs, plasmids and ESBL genes among Escherichia coli from humans, animals and food in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1178–82.

Perry KL, Walker GC. Identification of plasmid (pKM101)-coded proteins involved in mutagenesis and UV resistance. Nature. 1982;300:278–81.

Boyd ES, Barkay T. The mercury resistance operon: from an origin in a geothermal environment to an efficient detoxification machine. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:349.

Rozwandowicz M, Brouwer MSM, Fischer J, Wagenaar JA, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Guerra B, Mevius DJ, Hordijk J. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:1121–37.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard-10th ed. M07-A11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA; 2018.

Begum N, Shamsuzzaman SM: Emergence of CTX-M-15 producing E. coli O25b-ST131 clone in a tertiary care hospital of Bangladesh. Malays J Pathol 2016, 38:241–249.

Matsumura Y, Yamamoto M, Nagao M, Hotta G, Matsushima A, Ito Y, Takakura S, Ichiyama S. Emergence and spread of B2-ST131-O25b, B2-ST131-O16 and D-ST405 clonal groups among extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Japan. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2612–20.

Richter TKS, Hazen TH, Lam D, Coles CL, Seidman JC, You Y, Silbergeld EK, Fraser CM, Rasko DA: Temporal Variability of Escherichia coli Diversity in the Gastrointestinal Tracts of Tanzanian Children with and without Exposure to Antibiotics. mSphere 2018, 3.

Riley LW. Pandemic lineages of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:380–90.

Goswami C, Fox S, Holden M, Connor M, Leanord A, Evans TJ. Genetic analysis of invasive Escherichia coli in Scotland reveals determinants of healthcare-associated versus community-acquired infections. Microb Genom. 2018;4:1.

Hammad AM, Hoffmann M, Gonzalez-Escalona N, Abbas NH, Yao K, Koenig S, Allué-Guardia A, Eppinger M. Genomic features of colistin resistant Escherichia coli ST69 strain harboring mcr-1 on IncHI2 plasmid from raw milk cheese in Egypt. Infect Genet Evol. 2019;73:126–31.

National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council: Zambia Consolidated Guidelines for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection 2020. In Co-trimoxazole Preventive Therapy (Health Mo ed.; 2020.

Martin JN, Rose DA, Hadley WK, Perdreau-Remington F, Lam PK, Gerberding JL. Emergence of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance in the AIDS era. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1809–18.

Crewe-Brown HH, Reyneke MP, Khoosal M, Becker PJ, Karstaedt AS. Increase in trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole) resistance at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Soweto, in the AIDS era. S Afr Med J. 2004;94:440–2.

Lockman S, Hughes M, Powis K, Ajibola G, Bennett K, Moyo S, van Widenfelt E, Leidner J, McIntosh K, Mazhani L, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole on mortality in HIV-exposed but uninfected children in Botswana (the Mpepu Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e491–500.

Kalungia AC, Burger J, Godman B, Costa JO, Simuwelu C. Non-prescription sale and dispensing of antibiotics in community pharmacies in Zambia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1215–23.

Mudenda W, Chikatula E, Chambula E, Mwanashimbala B, Chikuta M, Masaninga F, Songolo P, Vwalika B, Kachimba JS, Mufunda J, Mweetwa B. Prescribing patterns and medicine use at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia. Med J Zambia. 2016;43:94–102.

Ofori-Asenso R, Brhlikova P, Pollock AM. Prescribing indicators at primary health care centers within the WHO African region: a systematic analysis (1995–2015). BMC Public Health. 2016;16:724.

Masich AM, Vega AD, Callahan P, Herbert A, Fwoloshi S, Zulu PM, Chanda D, Chola U, Mulenga L, Hachaambwa L, et al. Antimicrobial usage at a large teaching hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0228555.

Ssekatawa K, Byarugaba DK, Wampande E, Ejobi F. A systematic review: the current status of carbapenem resistance in East Africa. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:629.

Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1333–41.

Tian SF, Chu YZ, Chen BY, Nian H, Shang H: ISEcp1 element in association with blaCTX-M genes of E. coli that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamase among the elderly in community settings. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2011, 29:731–734.

Yoon E-J, Gwon B, Liu C, Kim D, Won D, Park SG, Choi JR, Jeong SH: Beneficial Chromosomal Integration of the Genes for CTX-M Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae for Stable Propagation. mSystems 2020, 5:e00459–00420.

Murray A, Mather H, Coia JE, Brown DJ: Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in nalidixic-acid-susceptible strains of Salmonella enterica isolated in Scotland. In J Antimicrob Chemother. Volume 62. England; 2008: 1153–1155

Aarestrup FM, Wiuff C, Mølbak K, Threlfall EJ. Is it time to change fluoroquinolone breakpoints for Salmonella spp.? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:827–9.

Novick RP, Clowes RC, Cohen SN, Curtiss R 3rd, Datta N, Falkow S. Uniform nomenclature for bacterial plasmids: a proposal. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:168–89.

Subbiah M, Top EM, Shah DH, Call DR. Selection pressure required for long-term persistence of blaCMY-2-positive IncA/C plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4486–93.

San Millan A, Peña-Miller R, Toll-Riera M, Halbert ZV, McLean AR, Cooper BS, MacLean RC. Positive selection and compensatory adaptation interact to stabilize non-transmissible plasmids. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5208.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) in Japan or Japan Society for the Promotion of Science under Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) to H.H. (Grant No. 17H01679 and 18K19436) and Y.F. (Grant No. 18K14672)., (AMED under Grant number JP21wm0125008 (the Japan Program for Infectious Diseases Research and Infrastructure) to H.H. and Y.F., World-leading Innovative and Smart Education (WISE) Grant-in Aid for Graduate Students to MSh., and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) scholarship for Advanced Training Program for Fostering Global Leaders on Infectious Disease Control to Build Resilience against Public Health Emergencies to MSh.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSh, YF, BH and HH designed the study, MSh, YF, GM, MM, EM, TZ, CK and MSi conducted the experiments, MSh, YF, BH and HH analyzed the data, MSh, YF, AP, BH and HH wrote the manuscript which was corrected and approved by all other co-authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by Excellence in Research Ethics and Science Converge with clearance number 2015-Feb-018, while Biological Transfer permit was approved by the National Health Research Ethics Board. All strains used in this study were isolated at the UTH during routine clinical investigations. The strains were identified on the basis of resistance to cefotaxime during routine susceptibility tests. Patient personal and clinical data were anonymized and unlinked to patient identifiers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary tables and figures (except Fig. S5).

Additional file 2.

Figure S5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shawa, M., Furuta, Y., Mulenga, G. et al. Novel chromosomal insertions of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 and diverse antimicrobial resistance genes in Zambian clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 10, 79 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00941-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00941-8