Abstract

Background

Recent research shows AKI increases the risk of incident CKD. We hypothesized that perioperative AKI may confer increased risk of subsequent CKD compared to nonperioperative AKI.

Methods

A MEDLINE search was performed for “AKI, CKD, chronic renal insufficiency, surgery, and perioperative” and related terms yielded 5209 articles. One thousand sixty-five relevant studies were reviewed. One thousand six were excluded because they were review, animal, or pediatric studies. Fifty-nine studies underwent full manuscript review by two independent evaluators. Seventeen met all inclusion criteria and underwent analysis. Two-by-two tables were constructed from AKI +/− and CKD +/− data. The R package metafor was employed to determine odds ratio (OR), and a random-effects model was used to calculate weighted ORs. Leave-1-out, funnel analysis, and structured analysis were used to estimate effects of study heterogeneity and bias.

Results

Nonperioperative studies included studies of oncology, percutaneous coronary intervention, and myocardial infarction patients. Perioperative studies comprised patients from cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, and burns. There was significant heterogeneity, but risk of bias was overall assessed as low. The OR for AKI versus non-AKI patients developing CKD in all studies was 4.31 (95% CI 3.01–6.17; p < 0.01). Nonperioperative subjects demonstrated OR 3.32 for developing CKD compared to non-AKI patients (95% CI 2.06–5.34; p < 0.01) while perioperative patients demonstrated OR 5.20 (95% CI 3.12–8.66; p < 0.01) for the same event.

Conclusions

We conclude that studies conducted in perioperative and nonperioperative patient populations suggest similar risk of development of CKD after AKI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rationale

Clinical and translational studies suggest that incident acute kidney injury (AKI) leads to chronic kidney disease (CKD). A systematic review and meta-analysis by Coca et al. (Coca et al. 2012) demonstrated patients with AKI had higher risk for developing CKD with a pooled adjusted hazard ratio of 8.8 compared to patients without AKI. Development of CKD after AKI is heterogeneous in that it occurs in a variety of patient populations and can be caused by plethora of disease processes, including sepsis, cardiovascular disease, nephrotoxin exposure, and surgically induced stressors. Surgery can affect long-term outcomes of nonsurgical disease; for example, surgical patients may have elevated risk of cognitive dysfunction (Bratzke et al. 2018) occurring remotely from surgery itself. Perioperative patients experience AKI due to additional etiologies not present in nonsurgical patients (for example, exposure to iodinated contrast followed by cardiac surgery, renal artery occlusion in vascular surgery, nephrectomy in oncologic surgery, or desquamation and resuscitation in burn surgery). Thus, additional mechanisms impacting AKI-CKD transition may be present in perioperative patients. Therefore, surgical patients may be subject to differential renal injury and experience elevated risk of AKI-CKD transition. We hypothesized that perioperative status might confer differential risk of developing CKD after an AKI event. Since AKI-CKD transition occurs in a delayed fashion, it may be possible to intervene in the latent interval between resolution of AKI and clinical CKD. Given the burden of suffering imposed by CKD, risk stratification of patients with perioperative AKI is desirable and could ultimately improve care.

Objectives

To perform subgroup analysis to determine whether risk of AKI-CKD transition varies according to perioperative or nonperioperative status.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Studies published from 1975 to 2018 available in the English language were eligible for initial review. We excluded reviews, animal studies, and pediatric studies to select for studies involving adult human subjects.

Information sources and search

MEDLINE search terms included AKI, CKD, chronic renal insufficiency, nephrotoxins, surgery, and perioperative.

Study selection

We included studies in which:

-

1)

Patients suffering AKI were included in the study

-

2)

The study clearly defined AKI and CKD

-

3)

The study excluded patients with prior CKD or separated patient data based on baseline kidney function (i.e., CKD stage, GFR) such that patients with CKD stage > 3 could be excluded from the analysis

-

4)

The study allowed determination of perioperative status

-

5)

The study stated CKD as an outcome

-

6)

The study included data necessary for calculation of effect size

In studies in which patients with prior CKD were not excluded, but patient data was separated based on baseline kidney function, only patients with baseline (pre-AKI) GFR > 60 or stage 1–2 CKD were included in the data analysis. We defined incident CKD as CKD stage 3 or higher, according to the definition stated within each study.

Data collection process and data items

Studies selected for final review were analyzed for the number of subjects in each of the categories:

-

1)

Patients who suffered AKI and developed subsequent CKD

-

2)

Patients who suffered AKI but did not develop CKD

-

3)

Patients who did not suffer AKI but developed CKD

-

4)

Patients who did not suffer AKI and did not develop CKD

Using these data, we calculated the OR for development of CKD in patients who suffered AKI vs. those who did not suffer AKI.

Risk of bias in individual studies

We assessed risk of bias in individual studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins et al. 2011). We did not assess performance bias or detection bias because there was no intervention applied to the patient populations being analyzed. Supplemental Table 1 presents the results of this analysis.

Statistical analysis including summary measures, synthesis of results, risk of bias across studies, and additional analyses

Statistical analysis was conducted using R package metafor. The OR was calculated for each study using a random effects model to compute each weighted OR and subgroup ORs. Summary subgroup ORs were compared using a random effects model, meta-regression, and Wald analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed with the Cochrane Q test and I2. Leave-1-out and funnel plots were also used to assess the effect of heterogeneity and publication bias.

Results

One thousand sixty-five studies were identified (Fig. 1). One thousand six studies were excluded after abstract review because they were animal studies, pediatric studies, or review articles. Fifty-nine studies underwent full manuscript review by two independent reviewers (PA, EAS). Seventeen studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and underwent analysis. The Kappa measure of agreement between independent reviewers was 0.84 (p < 0.001). Disagreements about inclusion of studies in the meta-analysis were resolved by discussion with the senior author (MPH), resulting in exclusion of four studies from the meta-analysis. Individual risk of bias for the studies included was low for sixteen of seventeen studies and high in one study, as demonstrated in Supplemental Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Ten of seventeen studies involved AKI in populations that were primarily perioperative (Wu et al. 2017; Palomba et al. 2017; Thalji et al. 2017; Legouis et al. 2017; Chew et al. 2017; Helgadottir et al. 2016; Arora et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2015; Rydén et al. 2014; Ishani et al. 2011). Of those, eight involved AKI in patients who underwent cardiac surgery (Wu et al. 2017; Palomba et al. 2017; Legouis et al. 2017; Chew et al. 2017; Helgadottir et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2015; Rydén et al. 2014; Ishani et al. 2011). The two remaining studies were in patients with burns (Thalji et al. 2017) and vascular surgery (Arora et al. 2015).

Seven studies described AKI to CKD transition in nonperioperative populations. These included patients undergoing coronary angiography/cardiac catheterization (James et al. 2010a; Helgason et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2016), non-myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation (Weiss et al. 2006), myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (Ando et al. 2010), suffering from myocardial infarction or pneumonia (Chawla et al. 2011), or with mixed medical etiologies (James et al. 2010b).

Quality assessment

Overall, there was significant heterogeneity across all studies (Q = 471.45, df = 16, p < 0.01; I2 = 98.3%). This was similar in perioperative studies (Q = 188.97, df = 9, p < 0.01; I2 = 93.7%) and nonperioperative studies (Q = 256.71, df = 6, p < 0.01; I2 = 97.9%).

Effect size

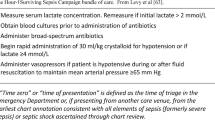

Figure 2 depicts the effect size for each study included in the meta-analysis. Overall, AKI was associated with increased risk of subsequent CKD (OR = 4.31; 95% CI 3.01–6.17; p = 1.7 × 10−15). In the subgroup of studies of perioperative patients, the risk of new onset CKD was 5.2 times greater in patients with AKI than in those without (OR = 5.20; 95% CI 3.12–8.66; p = 2.9 × 10−10). In the subgroup of nonperioperative patients, the effect size was similar to that in perioperative patients (nonperioperative OR = 3.32; 95% CI 2.06–5.34; p = 8.0 × 10−7). The difference in effect size between perioperative and nonperioperative studies was not statistically significant. Therefore, in the studies reviewed, the risk of new onset CKD is elevated in patients who suffer AKI. Perioperative status confers at least the same risk as nonperioperative status.

Discussion

The main finding of this meta-analysis is that studies conducted in perioperative populations demonstrate similar elevation of risk of AKI-CKD transition to those conducted in nonperioperative populations, with odds ratios of 5.20 and 3.32 respectively. Several groups have raised concerns that CKD could be a long-term outcome of perioperative AKI, and our data support this concern (Legouis et al. 2017; Palant et al. 2017). Numerous strategies to reduce the incidence of perioperative AKI are investigational (Romagnoli et al. 2018; Zarbock et al. 2018; Han and Lee 2019) and may therefore also potentially reduce postoperative development of CKD. Similarly, some have suggested patients with AKI receive surveillance for development of CKD (Fortrie et al. 2019); our results suggest this may be worthy of study in perioperative patients, in whom AKI may have a well-defined onset during a hospital stay, making them more amenable to intervention. It is widely speculated that intervention in the period between AKI and CKD development may ameliorate or even prevent CKD. For example, in cardiac surgery patients, with the advent of early biomarkers of AKI, it may be possible to predict incipient AKI as early as 6 h after surgery (Neyra et al. 2019), and 60% of AKI-CKD occurs within 1 year, while only 10% occurs within 160 days (Legouis et al. 2017). Therefore there is ample opportunity to identify at-risk patients and if possible, intervene. Although there is not yet a successful intervention, renin-angiotensin system inhibition, mediation of transforming growth-factor β and insulin-like growth factor, and antithrombin III have all been targets of investigation (Chou et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2020; Yin et al. 2017). Two clinical trials of interventions to prevent CKD after AKI (one of dietary intervention, NCT02831062 and one of intensified renal care, NCT4145609) are currently active. A critical translational step in monitoring patients after AKI would be development of specific biomarkers of AKI-CKD transition. Indeed, several have been proposed and recently reviewed (Wen and Parikh 2021); particularly hopeful may be urinary angiotensinogen, as this marker could also potentially be used to guide renin-angiotensin system based therapy (Cui et al. 2018). Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that with the right data, perioperative providers may be able to influence the course of AKI-CKD transition in the future. The present study suggests that perioperative patients have significant risk of AKI-CKD transition and points the way toward the data necessary for actionable knowledge.

A related secondary finding is that there is now a considerable dataset documenting AKI-CKD transition in many patient subgroups, such that subgroup analysis may be performed. We tested the hypothesis that perioperative status might modify risk, but other subgroup analyses are possible, and might further elucidate high risk populations. The present dataset does not allow determination of differential risk in specific surgical populations but suggests such studies are warranted and in the future could underpin risk stratification, potentially supporting intervention. For example, we note that two studies demonstrating lowest risk (Ishani et al. 2011, and Legouis et al. 2017), respectively evaluate CABG patients only and patients with low preoperative risk score (mean propensity-matched logistic EUROscore 4.3) and short cardiopulmonary bypass times (mean 79 min) consistent with a high proportion of CABG cases. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that patients requiring burn surgery and valve, heart transplant, or adult congenital heart surgery may have higher risk of AKI-CKD transition, while patients undergoing CABG alone may experience lower risk relative to that of more complex heart surgery. Further studies are warranted to address this potential signal. With additional studies of subpopulations of perioperative patients, risk stratification for surgical AKI-CKD may be possible.

Finally, we acknowledge this study has limitations. The primary limitation is significant heterogeneity across studies. To some degree, this should be expected given the broad nature of the subgroups included in this analysis. It should be noted that definitions of AKI varied among studies; this may be a source of heterogeneity. The nonperioperative subgroup in particular constitutes a broad collection of studies including various disease types and concurrently a broad patient population. A second limitation of the nonperioperative group is that it is not possible to ensure that all patients in nonperioperative populations did not have surgical exposure, increasing the risk of type 2 error. In perioperative studies, there was little diversity in the type of surgical procedures as nearly all studies of perioperative AKI-CKD have occurred in cardiac surgery patients who have high risk of AKI. This highlights an area for further investigation as risk seems likely to vary according to type of surgery. For example, same day/elective surgeries (e.g., cholecystectomy, appendectomy) may result in low-grade AKI (i.e., smaller changes in baseline creatinine) and thus may pose less risk of subsequent CKD compared to larger or emergent surgical procedures.

Conclusions

We conclude that studies conducted in perioperative and nonperioperative patient populations suggest similar risk of development of CKD after AKI.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

09 July 2021

The XML tagging of the author names has been corrected.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Ando M, Ohashi K, Akiyama H, Sakamaki H, Morito T, Tsuchiya K, et al. Chronic kidney disease in long-term survivors of myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation: prevalence and risk factors. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(1):278–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfp485.

Arora P, Davari-Farid S, Pourafkari L, Gupta A, Dosluoglu HH, Nader ND. The effect of acute kidney injury after revascularization on the development of chronic kidney disease and mortality in patients with chronic limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3):720–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.020.

Bratzke LC, Koscik RL, Schenning KJ, Clark LR, Sager MA, Johnson SC, et al. Cognitive decline in the middle-aged after surgery and anaesthesia: results from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention cohort. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(5):549–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14216.

Brown JR, Solomon RJ, Robey RB, Plomondon ME, Maddox TM, Marshall EJ, et al. Chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular outcomes following cardiac catheterization-a population-controlled study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(10). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003812.

Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. The severity of acute kidney injury predicts progression to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79(12):1361–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.42.

Chew STH, Ng RRG, Liu W, Chow KY, Ti LK. Acute kidney injury increases the risk of end-stage renal disease after cardiac surgery in an Asian population: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-017-0476-y.

Chou YH, Chu TS, Lin SL. Role of renin-angiotensin system in acute kidney injury-chronic kidney disease transition. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018;23(Suppl 4):121–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.13467.

Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012;81(5):442–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.379.

Cui S, Wu L, Feng X, Su H, Zhou Z, Luo W, et al. Urinary angiotensinogen predicts progressive chronic kidney disease after an episode of experimental acute kidney injury. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018;132(19):2121–33. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20180758.

Fortrie G, de Geus HRH, Betjes MGH. The aftermath of acute kidney injury: a narrative review of long-term mortality and renal function. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2314-z.

Gao L, Zhong X, Jin J, Li J, Meng XM. Potential targeted therapy and diagnosis based on novel insight into growth factors, receptors, and downstream effectors in acute kidney injury and acute kidney injury-chronic kidney disease progression. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0106-1.

Han SJ, Lee HT. Mechanisms and therapeutic targets of ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2019;38(4):427–40. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.19.062.

Helgadottir S, Sigurdsson MI, Palsson R, Helgason D, Sigurdsson GH, Gudbjartsson T. Renal recovery and long-term survival following acute kidney injury after coronary artery surgery: a nationwide study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60(9):1230–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12758.

Helgason D, Long TE, Helgadottir S, Palsson R, Sigurdsson GH, Gudbjartsson T, et al. Acute kidney injury following coronary angiography: a nationwide study of incidence, risk factors and long-term outcomes. J Nephrol. 2018;31(5):721–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-018-0534-y.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(oct18 2):d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Ishani A, Nelson D, Clothier B, Schult T, Nugent S, Greer N, et al. The magnitude of acute serum creatinine increase after cardiac surgery and the risk of chronic kidney disease, progression of kidney disease, and death. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(3):226–33. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.514.

James MT, Ghali WA, Tonelli M, Faris P, Knudtson ML, Pannu N, et al. Acute kidney injury following coronary angiography is associated with a long-term decline in kidney function. Kidney Int. 2010a;78(8):803–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2010.258.

James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Wiebe N, Pannu N, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW, et al. Glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, and the incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010b;376(9758):2096–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61271-8.

Legouis D, Galichon P, Bataille A, Chevret S, Provenchere S, Boutten A, et al. Rapid occurrence of chronic kidney disease in patients experiencing reversible acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(1):39–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001400.

Neyra JA, Hu MC, Minhajuddin A, Nelson GE, Ahsan SA, Toto RD, et al. Kidney tubular damage and functional biomarkers in acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4(8):1131–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2019.05.005.

Palant CE, Amdur RL, Chawla LS. Long-term consequences of acute kidney injury in the perioperative setting. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(1):100–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000428.

Palomba H, Castro I, Yu L, Burdmann EA. The duration of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery increases the risk of long-term chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2017;30(4):567–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-016-0351-0.

Romagnoli S, Ricci Z, Ronco C. Perioperative acute kidney injury: prevention, early recognition, and supportive measures. Nephron. 2018;140(2):105–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490500.

Rydén L, Sartipy U, Evans M, Holzmann MJ. Acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting and long-term risk of end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2005–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010622.

Thalji SZ, Kothari AN, Kuo PC, Mosier MJ. Acute kidney injury in burn patients: clinically significant over the initial hospitalization and 1 year after injury: an original retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(2):376–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001979.

Weiss AS, Sandmaier BM, Storer B, Storb R, McSweeney PA, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease following non-myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(1):89–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01131.x.

Wen Y, Parikh CR. Current concepts and advances in biomarkers of acute kidney injury. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2021:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2021.1879000.

Wu B, Ma L, Shao Y, Liu S, Yu X, Zhu Y, et al. Effect of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury on long-term outcomes of Chinese patients: a historical cohort study. Blood Purif. 2017;44(3):227–33. https://doi.org/10.1159/000478967.

Xu JR, Zhu JM, Jiang J, Ding XQ, Fang Y, Shen B, et al. Risk Factors for long-term mortality and progressive chronic kidney disease associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(45):e2025. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002025.

Yin J, Wang F, Kong Y, Wu R, Zhang G, Wang N, et al. Antithrombin III prevents progression of chronic kidney disease following experimental ischaemic-reperfusion injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(12):3506–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13261.

Zarbock A, Koyner JL, Hoste EAJ, Kellum JA. Update on perioperative acute kidney injury. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(5):1236–45. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003741.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This material was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development (VA Merit Award #1I01BX004288 to MPH) and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (F30 DK114980-03 to EAS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PA performed the literature search. PA and ES were responsible for the study selection, review, and collection of data. MH resolved disagreements in the study selection and performed the statistical analysis of the data. PA, ES, and MH contributed to manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Results of assessment for bias.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdala, P.M., Swanson, E.A. & Hutchens, M.P. Meta-analysis of AKI to CKD transition in perioperative patients. Perioper Med 10, 24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-021-00192-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-021-00192-6