Abstract

In this article, we consider a temporally second-order unconditionally energy stable computational method for the Allen–Cahn (AC) equation with a high-order polynomial free energy potential. By modifying the nonlinear parts in the governing equation, we have a linear convex splitting scheme of the energy for the high-order AC equation. In addition, by combining the linear convex splitting with a strong-stability-preserving implicit–explicit Runge–Kutta (RK) method, the proposed method is linear, temporally second-order accurate, and unconditionally energy stable. Computational tests are performed to demonstrate that the proposed method is accurate, efficient, and energy stable.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Phase-field equations have arisen as a significant numerical framework in modeling and studying evolution of pattern formation in materials [1]. In general, phase-field models are driven by gradient flows for the governing total energy functionals [2, 3], e.g., the Ginzburg–Landau (GL) free energy functional:

where Ω is a domain in \(\mathbb{R}^{d}\) (\(d=1,2,3\)), ϕ is the order parameter, \(F(\phi ) = \frac{1}{4} (\phi ^{2}-1)^{2}\) is the GL potential, and \(\epsilon >0\) is a constant. We assume the homogeneous Neumann boundary condition for ϕ: \(\nabla \phi \cdot {\mathbf{n}} = 0\) on ∂Ω, where n is normal to ∂Ω. The \(L^{2}\)-gradient flow for (1) is the Allen–Cahn (AC) equation [4].

Various computational methods have been proposed to solve the AC equation [5–16]. Shen and Yang [5] and Long et al. [6] presented a second-order semiimplicit method based on a second-order backward differentiation formula with a stabilizing term. Guan et al. [7] and Bu et al. [8] developed second-order schemes using the convex splitting (CS) method [17, 18] and the secant scheme [19]. In [9], Lee and Lee developed a second-order semianalytical Fourier spectral method. Guillén-González and G. Tierra [10] and Li et al. [11] presented a second-order semiimplicit Crank–Nicolson (CN) method. In [12], Shin et al. proposed a second-order CS method based on the implicit–explicit (IMEX) Runge–Kutta (RK) method [20]. In [13], Ji et al. developed CN formulas using the invariant energy quadratization idea [21] and the scalar auxiliary variable approach [22]. In [14], Zhang et al. proposed a second-order scheme using the stabilized scalar auxiliary variable method [23].

Recently, the AC equation with a high-order polynomial \(F_{p}(\phi ) = \frac{1}{4} (\phi ^{p} - 1)^{2}\), referred to as the hAC equation, was introduced to better represent the interfacial dynamics [24]. Here, p is an even integer.

For more background information about the hAC equation, let us consider the origin of the standard quartic polynomial free energy, \(F(\phi ) = \frac{1}{4} (\phi ^{2}-1)^{2}\). In the original derivation of the bulk free energy in the total free energy functional \(\mathcal{E}(\phi )\), the following logarithmic free energy was used:

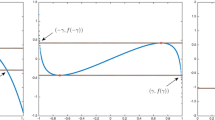

where θ and \(\theta _{c}\) are the absolute and the critical temperatures, respectively [25]. However, the logarithmic bulk free energy function has singularities at \(\phi = \pm 1\). Therefore, for computational efficiency, a quartic polynomial approximation \(F(\phi ) = \frac{1}{4}(\phi ^{2} - 1)^{2}\) has been used instead of the logarithmic potential. The AC equation has been successfully applied as a building block equation for modeling many scientifically and industrially important problems such as crystal growth, image segmentation, motion by mean curvature, tissue growth, volume repairing and smoothing, topology optimization, volume reconstruction from point cloud and slice data, and multiphase fluid flows [24]. However, the AC equation with the classical quartic polynomial function has a limitation in preserving structures. For example, as we will show that with a numerical experiment in the later section, if two separated components are close to each other, then they may merge with each other. To resolve this problem, we use the hAC equation which has a good structure preserving property. As shown in Fig. 1, the higher the order p, the larger the free energy barrier. This fact implies that once two different phases are separated, they remain separated, which is a good feature in modeling the dynamics of complex shapes.

Compared to the AC equation, the hAC equation is less studied numerically [24]. The main purpose of this article is to develop a second-order energy stable method for the hAC equation, which is based on the CS idea. For \(F_{p}(\phi )\), one can split into \(\frac{1}{4} \phi ^{2p} + \frac{1}{4}\) and \(-\frac{1}{2} \phi ^{p}\), however, the resulting method is highly nonlinear thus its numerical implementation is complicated. In this study, we propose a linear CS that can be applied to all p, by placing \(\frac{1}{4} (\phi ^{p} - 1)^{2}\) in the concave part. In addition, we combine the linear CS with a strong-stability-preserving (SSP) IMEX-RK method [26] to obtain temporally second-order accurate and unconditionally energy stable scheme.

The contents of this article are as follows. We present the linear CS scheme with an auxiliary term in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we propose the second-order CS method, prove unconditional energy stability, and describe the computational implementation. In Sect. 4, we present computational tests to demonstrate the performance of the method. Conclusions are given in Sect. 5.

2 Linear convex splitting with an auxiliary term

It is well known that the AC equation preserves the maximum principle [27]. Thus, like a common practice to consider the AC and Cahn–Hilliard equations with the truncated Ginzburg–Landau double-well potential [5, 28–32], we can replace \(\frac{1}{4} (\phi ^{p} - 1)^{2}\) by

where \(A = \frac{p^{2}}{2}\), \(B = \frac{p^{2}}{2}\), and \(C = \frac{p^{2}}{4}\).

Remark 1

With the replacement of \(\frac{1}{4} (\phi ^{p} - 1)^{2}\) by \({\tilde{F}}_{p}(\phi )\), we have

Therefore, the hAC equation can be rewritten as follows:

Next, we consider the following splitting \(\mathcal{E} (\phi ) = \mathcal{E}_{c} (\phi ) - \mathcal{E}_{e} ( \phi )\):

where \(\beta \geq 0\) is a constant.

Lemma 1

Both \(\mathcal{E}_{c} (\phi )\) and \(\mathcal{E}_{e} (\phi )\) in (3) are convex if \(\beta \geq A\).

Proof

For \(\mathcal{E}_{c} (\phi )\), we have

Then, we obtain

For \(\mathcal{E}_{e} (\phi )\), we get

Then, we have

Therefore, the convexity condition of \(\mathcal{E}_{c} (\phi )\) and \(\mathcal{E}_{e} (\phi )\) is satisfied if \(\beta \geq A\). □

Lemma 2

The convexity condition of \({\mathcal{E}}_{c}(\phi )\) and \({\mathcal{E}}_{e}(\phi )\) results in the following inequality:

where \(( \cdot , \cdot )_{L^{2}}\) denotes the \(L^{2}\)-inner product with respect to Ω.

Proof

For \({\mathcal{E}}_{c}(\phi )\), we have

And we obtain for \({\mathcal{E}}_{e}(\phi )\) with \(\beta \geq A\),

where φ is between ϕ and ψ. Then, subtracting (6) from (5) yields inequality (4). □

3 Unconditionally stable second-order scheme

Next, we propose a second-order CS scheme for the hAC equation by combining the linear CS (3) with the specially designed second-order (three-stage) SSP-IMEX-RK scheme:

where \(a_{10}\), \(a_{11}\), \(a_{20}\), \(a_{21}\), \(a_{22}\), \(b_{1}\), \(b_{2}\) satisfy the second-order conditions and the stability condition [26], and are as follows:

Theorem 1

The method (7) with \(\beta \geq A\) is unconditionally energy stable, i.e., we have the following inequality:

for any time step \(\Delta t > 0\).

Proof

Let \(\mu (\phi ,\psi ) = \frac{\delta {\mathcal{E}}_{c}(\phi )}{\delta \phi } - \frac{\delta {\mathcal{E}}_{e}(\psi )}{\delta \phi }\) for simplicity of notation. From the second and third steps of (7), we obtain

and

Using Lemma 2, we obtain

This completes the proof. □

3.1 Numerical implementation

We can rewrite the first-step of (7) as

where \(L= \beta / \epsilon ^{2} - \Delta \). Then, we have

where we have used the zero Neumann boundary condition for ϕ. In the same way,

and

The Fourier spectral method [33–38] with the discrete cosine transform in MATLAB is used.

4 Computational experiments

4.1 Convergence test

We investigate the performance of the proposed scheme with an initial condition

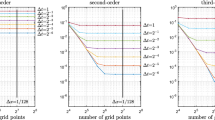

on \(\Omega =[0,1]\). We set \(\epsilon =0.02\) and \(\beta =0\); and calculate \(\phi (x,t)\) for \(0 < t \le t_{f}=5\epsilon ^{2}\). To demonstrate spatial accuracy of the numerical solution, computations are done by changing the number of grid points \(16,24,\ldots ,256\). Figure 2 displays the relative \(l_{2}\)-errors of \(\phi (x,t_{f})\) with \(p=4,6,8,10\) for different numbers of grid points and time steps. The errors are calculated by comparing with the reference numerical solution using 512 grid points and \(\Delta t = t_{f}/2^{14}\). As we can observe in Fig. 2, the spatial convergence of the scheme under grid refinement is evident.

Next, to calculate the temporal convergence rate, computations are done by fixing \(\Delta x = 1/128\) and changing \(\Delta t=t_{f}/2^{12}, t_{f}/2^{11}, \ldots , t_{f}/2^{7}\). We use the quadruply over-resolved computational result as the reference numerical solution. Figure 3(a) displays the relative \(l_{2}\)-errors of \(\phi (x,t_{f})\) with \(p=4,6,8,10\) for different time steps. The errors are calculated by comparing with the reference numerical solution. The result shows that the scheme is second-order accurate in time for all p. In addition, Fig. 3(b) shows the average CPU time consumed using the method with \(p=4,6,8,10\) for different Δt. The computational results indicates that the average CPU time is almost linear with respect to the number of steps and not affected by p.

4.2 Energy stability test

To study the energy stability of the proposed method, let us consider the following initial condition on \(\Omega =[0,1]\times [0,1]\):

where \(\operatorname{rand}(x,y)\) is a random number between \([-0.9, 0.9]\). We use \(\epsilon =0.005\), \(\beta = p^{2}/2\), and \(\Delta x=\Delta y=1/128\). Figure 4 displays the temporal evolution of the discrete energy with various Δt for \(p=4,6,8,10\). And the temporal evolution of the discrete energy with \(\Delta t = 2^{19} \epsilon ^{2} \approx 13\) for \(p=4,6,8,10\) is displayed in Fig. 5. For all p and large time steps, all the discrete total energies are temporally decreasing. Figure 6 displays the temporal evolution of \(\phi (x,y,t)\) with \(\Delta t=2^{4} \epsilon ^{2}\) for all p.

4.3 Motion by mean curvature

Suppose a radially symmetric initial condition is given as follows:

which represents a circle centered at \((a,b)\) with an initial radius \(R_{0}\). It is well known that the solution of the AC equation follows the motion by mean curvature. Therefore, the radius \(R(t)\) of the interfacial circle (where \(\phi (x,y,t)=0\)) shrinks at the rate of the curvature of the circle:

To compare the original AC equation and the hAC equation for the mean curvature flow, the computational domain \(\Omega =[0,1]\times [0,1]\), \((a,b)=(0.5,0.5)\), \(R_{0}=0.35\), \(\epsilon =0.02\), \(\beta = 0\), \(\Delta x=\Delta y=1/128\), and \(\Delta t=10^{-5}\) are used. Figure 7(a) displays the evolution of the radius of the interfacial circle for \(p=2,4,6,8,10\). And the interfacial layer (from \(\phi =-0.95\) to \(\phi =0.95\)) at \(t=0.05\) for \(p=2\) and 10 is displayed in Fig. 7(b). The results suggest that the hAC equation can generate a sharper interface than the original AC equation.

4.4 Effect of p on the interfacial dynamics in 2D

To investigate the effect of p in the hAC equation on the interfacial dynamics in 2D, we consider two circles on \(\Omega =[0,2]\times [0,1]\) (see the first column of Fig. 8(a)). Their centers are \((0.667,0.5)\) and \((1.333,0.5)\), respectively, and radii are 0.3, and we set \(\phi (x,y,0)\) to 1 inside the circles and −1 otherwise. We choose \(\epsilon =0.02\), \(\beta = 0\), \(\Delta x=\Delta y=1/128\), and \(\Delta t=10^{-5}\). Figure 8 displays the evolution of \(\phi (x,y,t)\) for \(p=2\) and 10. The initial two circles merge into one when \(p=2\), whereas shrink without merging when \(p=10\).

4.5 Effect of p on the interfacial dynamics in 3D

To examine the effect of p in the hAC equation on the interfacial dynamics in 3D, we consider a three-dimensional spiral on \(\Omega =[0,1]\times [0,1]\times [0,1]\) (see the first column of Fig. 9) [24]. The width and height of the spiral are \(8\Delta x\) and \(58\Delta x\), respectively, and we set \(\phi (x,y,z,0)\) to 1 inside the spiral and −1 otherwise. We use \(\Delta x=\Delta y=\Delta z=\frac{1}{64}\), \(\epsilon =\Delta x\), \(\beta = p^{2}/2\), and \(\Delta t=10\epsilon ^{2}\). Figures 9 and 10 display the evolution of \(\phi (x,y,z,t)\) and energy for \(p=4,6,8,10\). As p increases, the high-order polynomial free energy term \(\int _{\Omega }\frac{F_{p}(\phi )}{\epsilon ^{2}} \,d\mathbf{x}\) influences the evolution of ϕ more strongly than the interfacial energy term \(\int _{\Omega }\frac{1}{2} |\nabla \phi |^{2} \,d\mathbf{x}\). As a result, ϕ loses its spiral shape by merge as p decreases, whereas ϕ still shows a spiral shape maintaining its interface as p increases.

5 Conclusions

We developed a linear, second-order, and unconditionally energy stable method for the hAC equation. In order to handle \(\int _{\Omega }{\tilde{F}}_{p}(\phi ) \,d\mathbf{x}\), \(\frac{\beta }{2\epsilon ^{2}} \int _{\Omega }\phi ^{2} \,d\mathbf{x}\) is added, which yields the linear convex–concave decomposition of the total energy for \(\beta \geq A\). In addition, we combined the linear CS with the specially designed second-order SSP-IMEX-RK scheme. We demonstrated that the proposed method is efficient and unconditionally energy stable, and second-order temporally accurate. In addition, we confirmed that the hAC equation has different interfacial dynamics depending on the value of p.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Chen, L.-Q.: Phase-field models for microstructure evolution. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 32, 113–140 (2002)

Cahn, J.W., Hilliard, J.E.: Free energy of a nonuniform system. I. Interfacial free energy. J. Chem. Phys. 28, 258–267 (1958)

Swift, J., Hohenberg, P.C.: Hydrodynamic fluctuations at the convective instability. Phys. Rev. A 15, 319–328 (1977)

Allen, S.M., Cahn, J.W.: A microscopic theory for antiphase boundary motion and its application to antiphase domain coarsening. Acta Metall. 27, 1085–1095 (1979)

Shen, J., Yang, X.: Numerical approximations of Allen–Cahn and Cahn–Hilliard equations. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., Ser. A 28, 1669–1691 (2010)

Long, J., Luo, C., Yu, Q., Li, Y.: An unconditional stable compact fourth-order finite difference scheme for three dimensional Allen–Cahn equation. Comput. Math. Appl. 77, 1042–1054 (2019)

Guan, Z., Lowengrub, J.S., Wang, C., Wise, S.M., Hu, Z., Wise, S.M., Wang, C., Lowengrub, J.S.: Second order convex splitting schemes for periodic nonlocal Cahn–Hilliard and Allen–Cahn equations. J. Comput. Phys. 277, 48–71 (2014)

Bu, L., Mei, L., Hou, Y.: Stable second-order schemes for the space-fractional Cahn–Hilliard and Allen–Cahn equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 78, 3485–3500 (2019)

Lee, H.G., Lee, J.-Y.: A semi-analytical Fourier spectral method for the Allen–Cahn equation. Comput. Math. Appl. 68, 174–184 (2014)

Guillén-González, F., Tierra, G.: Second order schemes and time-step adaptivity for Allen–Cahn and Cahn–Hilliard models. Comput. Math. Appl. 68, 821–846 (2014)

Li, C., Huang, Y., Yi, N.: An unconditionally energy stable second order finite element method for solving the Allen–Cahn equation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 353, 38–48 (2019)

Shin, J., Lee, H.G., Lee, J.-Y.: Convex splitting Runge–Kutta methods for phase-field models. Comput. Math. Appl. 73, 2388–2403 (2017)

Ji, B., Liao, H.-L., Gong, Y., Zhang, L.: Adaptive linear second-order energy stable schemes for time-fractional Allen–Cahn equation with volume constraint. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 90, 105366 (2020)

Zhang, J., Chen, C., Yang, X., Chu, Y., Xia, Z.: Efficient, non-iterative, and second-order accurate numerical algorithms for the anisotropic Allen–Cahn equation with precise nonlocal mass conservation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 363, 444–463 (2020)

Khater, M.M.A., Park, C., Lu, D., Attia, R.A.M.: Analytical, semi-analytical, and numerical solutions for the Cahn–Allen equation. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 9 (2020)

Khalid, N., Abbas, M., Iqbal, M.K., Baleanu, D.: A numerical investigation of Caputo time fractional Allen–Cahn equation using redefined cubic B-spline functions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 158 (2020)

Elliott, C.M., Stuart, A.M.: The global dynamics of discrete semilinear parabolic equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 30, 1622–1663 (1993)

Eyre, D.J.: Unconditionally gradient stable time marching the Cahn–Hilliard equation. MRS Proc. 529, 39–46 (1998)

Du, Q., Nicolaides, R.A.: Numerical analysis of a continuum model of phase transition. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 28, 1310–1322 (1991)

Ascher, U.M., Ruuth, S.J., Spiteri, R.J.: Implicit–explicit Runge–Kutta methods for time-dependent partial differential equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 25, 151–167 (1997)

Yang, X.: Linear, first and second-order, unconditionally energy stable numerical schemes for the phase field model of homopolymer blends. J. Comput. Phys. 327, 294–316 (2016)

Shen, J., Xu, J., Yang, J.: The scalar auxiliary variable (SAV) approach for gradient flows. J. Comput. Phys. 353, 407–416 (2018)

Chen, C., Yang, X.: Fast, provably unconditionally energy stable, and second-order accurate algorithms for the anisotropic Cahn–Hilliard model. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 351, 35–59 (2019)

Lee, C., Kim, H., Yoon, S., Kim, S., Lee, D., Park, J., Kwak, S., Yang, J., Wang, J., Kim, J.: An unconditionally stable scheme for the Allen–Cahn equation with high-order polynomial free energy. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 95, 105658 (2021)

Lee, D., Huh, J.-Y., Jeong, D., Shin, J., Yun, A., Kim, J.: Physical, mathematical, and numerical derivations of the Cahn–Hilliard equation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 81, 216–225 (2014)

Lee, H.G.: Stability condition of the second-order SSP-IMEX-RK method for the Cahn–Hilliard equation. Mathematics 8, 11 (2020)

Evans, L.C., Soner, H.M., Souganidis, P.E.: Phase transitions and generalized motion by mean curvature. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 45, 1097–1123 (1992)

Shen, J., Yang, X.: Energy stable schemes for Cahn–Hilliard phase-field model of two-phase incompressible flows. Chin. Ann. Math., Ser. B 31, 743–758 (2010)

Wu, X., van Zwieten, G.J., van der Zee, K.G.: Stabilized second-order convex splitting schemes for Cahn–Hilliard models with application to diffuse-interface tumor-growth models. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 30, 180–203 (2014)

Bu, L., Mei, L., Wang, Y., Hou, Y.: Energy stable numerical schemes for the fractional-in-space Cahn–Hilliard equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 158, 392–414 (2020)

Wang, L., Yu, H.: An energy stable linear diffusive Crank–Nicolson scheme for the Cahn–Hilliard gradient flow. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 377, 112880 (2020)

Zhao, S., Xiao, X., Feng, X.: An efficient time adaptivity based on chemical potential for surface Cahn–Hilliard equation using finite element approximation. Appl. Math. Comput. 369, 124901 (2020)

Lee, H.G.: A new conservative Swift–Hohenberg equation and its mass conservative method. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 375, 112815 (2020)

Lee, H.G.: An efficient and accurate method for the conservative Swift–Hohenberg equation and its numerical implementation. Mathematics 8, 1502 (2020)

Shin, J., Lee, H.G., Lee, J.-Y.: Long-time simulation of the phase-field crystal equation using high-order energy-stable CSRK methods. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 364, 112981 (2020)

Shin, J., Lee, H.G.: A linear, high-order, and unconditionally energy stable scheme for the epitaxial thin film growth model without slope selection. Appl. Numer. Math. 163, 30–42 (2021)

Zhang, J., Wang, J., Zhou, Y.: Numerical analysis for time-fractional Schrödinger equation on two space dimensions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 53 (2020)

Fei, M., Zhang, G., Wang, N., Huang, C.: A linearized conservative Galerkin–Legendre spectral method for the strongly coupled nonlinear fractional Schrödinger equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 661 (2020)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewers for the constructive and helpful comments on the revision of this article.

Funding

The first author (J. Kim) was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2019R1A2C1003053). The corresponding author (H.G. Lee) was supported by the Research Grant of Kwangwoon University in 2021 and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2019R1C1C1011112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this study and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Lee, H.G. Unconditionally energy stable second-order numerical scheme for the Allen–Cahn equation with a high-order polynomial free energy. Adv Differ Equ 2021, 416 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03571-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03571-x