Abstract

Viruses can be spread and transmitted through two fundamental modes, one by virus-to-cell infection and the other by direct cell-to-cell transmission. In this paper, we propose a new generalized virus dynamics model, which incorporates both modes and takes into account the cure of infected cells. We first show mathematically and biologically the well-posedness of our model. Further, an explicit formula for the basic reproduction number \(R_{0}\) of the model is determined. By analyzing the characteristic equations we establish the local stability of the disease-free equilibrium and the chronic infection equilibrium in terms of \(R_{0}\). The global behavior of the model is investigated by constructing an appropriate Lyapunov functional for disease-free equilibrium and by applying geometrical approach to chronic infection equilibrium. Moreover, mathematical virus models and results presented in many previous studies are generalized and improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Many viruses infect humans and cause different infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), Ebola virus, and more recently Zika virus. They are often transmitted in body by two fundamentally distinct modes, either by virus-to-cell infection through the extracellular space or by cell-to-cell transmission involving direct cell-to-cell contact [1–4]. During both infection modes, a part of infected cells returns to the uninfected state by loss of all covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) from their nucleus [5–7]. To model viral infection dynamics, several mathematical models have been proposed and developed. Most of these models are based on the assumption that healthy cells can only be infected by viruses, and so they consider only the virus-to-cell infection mode. However, there are few virus dynamics models in the literature with both modes of transmission and taking into account the cure of infected cells.

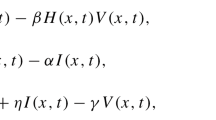

Motivated by the mentioned biological and mathematical considerations, we propose the following generalized virus dynamics model with two transmission modes and cure rate:

where \(x(t)\), \(y(t)\), and \(v(t)\) denote the concentrations of uninfected cells, infected cells, and free viruses at time t, respectively, λ is the recruitment rate of uninfected cells, ρ is the cure rate of infected cells, k is the production rate of free viruses by infected cells, and d, a, and u are the death rates of uninfected cells, infected cells, and free viruses, respectively. In addition, healthy cells become infected either by free viruses at rate \(f(x,y,v)v\) or by direct contact with an infected cell at rate \(g(x,y)y\). Hence, the term \(f(x,y,v)v+g(x,y)y\) represents the total infection rate of uninfected cells.

The incidence function \(g(x,y)\) for direct cell-to-cell transmission mode is assumed to be continuously differentiable in the interior of \(\mathbb{R}^{2}_{+}\) and satisfy the following property:

- (H0):

-

\(g(0,y)=0\) for all \(y\geq0\), \(\frac{\partial g}{\partial x}(x,y)\geq0\) (or \(g(x,y)\) is a strictly increasing function with respect to x when \(f\equiv0\)), and \(\frac{\partial g}{\partial y}(x,y)\leq0\) for all \(x\geq0\) and \(y \geq0\).

Further, the incidence function \(f(x,y,v)\) for virus-to-cell infection mode is assumed to be continuously differentiable in the interior of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\) and has the properties similar to those assumed in [8]:

- (H1):

-

\(f(0,y,v)=0\) for all \(y\geq0\) and \(v\geq0\),

- (H2):

-

\(f(x,y,v)\) is a strictly increasing function with respect to x (or \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x,v,y)\geq0\) when \(g(x,y)\) is a strictly increasing function with respect to x) for any fixed \(y\geq0\) and \(v\geq0\),

- (H3):

-

\(f(x,y,v)\) is a decreasing function with respect to y and v, that is, \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x,y,v)\leq0\) and \(\frac{ \partial f}{\partial v}(x,y,v)\leq0\) for all \(x\geq0\), \(y\geq0\), and \(v\geq0\).

The first assumption on the function \(g(x,y)\) means that the incidence rate by cell-to-cell transmission is equal to zero if there are no susceptible cells. This incidence rate is increasing when the numbers of infected cells are constant and the number of susceptible cells increases. Biologically speaking, the greater the amount of susceptible cells, the greater the average number of cells infected by direct contact with an infected cell in the unit time. Similarly, the last assumption on the function \(g(x,y)\) means that the greater the amount of infected cells, the lower the average number of cells infected by direct contact in the unit time. Therefore, the three hypotheses summarized in assumption (H0) are reasonable and consistent with the reality. For the biological significance of three hypotheses (H1)-(H3) on the function \(f(x,y,v)\), we refer the reader to [9, 10]. Furthermore, the four assumptions (H0)-(H3) are satisfied by most incidence rates existing in the literature.

On the other hand, system (1) includes various special cases. For example, when we ignore the cell-to-cell transmission mode (i.e., \(g\equiv0\)), we obtain the model of Hattaf et al. [8], which is a generalization of many classical models presented in [6, 11–19]. However, when only the cell-to-cell transmission mode is considered, we have \(f\equiv0\), and the model (1) is reduced to

Notice that the model of Bonhoeffer et al. [20] is a particular case of system (2). When both virus-to-cell and cell-to-cell transmission modes are considered with \(f(x,y,v)=\beta_{1}x\) and \(g(x,y)=\beta_{2}x\), we get the model of Zhang et al. [21]. In this work, we aim to study the dynamical behavior of system (1) with general incidence functions for both modes. In addition, we improve the results of Zhang et al. by proving that the global stability of the model [21] is completely determined by the value of a certain threshold parameter called the basic reproduction number \(R_{0}\).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section deals with some preliminary results about the positivity and boundedness of solutions, the basic reproduction number, and the existence of equilibria. In Section 3, we establish the local stability of the disease-free equilibrium and the chronic infection equilibrium. The global stability of both equilibria is investigated in Section 4. The paper ends with some applications of our results in Section 5.

2 Preliminary results

In this section, we first show that the solutions of system (1) with nonnegative initial conditions remain nonnegative and bounded for all \(t\geq0\).

Let \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}=\{(x,y,v)\in\mathbb{R}^{3} : x\geq0, y\geq 0, v\geq0\} \). We have the following result.

Theorem 2.1

The first quadrant \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\) is positively invariant with respect (1). Moreover, all solutions of (1) are uniformly bounded in the compact subset

Proof

Obviously, \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\) is positively invariant with respect (1). It remains to prove that all solutions of system (1) are uniformly bounded.

Let \((x(t),y(t),v(t) )\) be any solution with nonnegative initial conditions \((x_{0},y_{0},v_{0})\). Adding the first two equations of system (1), we obtain

Hence,

Similarly, from the third equation of system (1) we get

Therefore, all solutions of system (1) starting in \(\mathbb{R} ^{3}_{+}\) are eventually confined in the region Γ. This completes the proof. □

This theorem shows mathematically and biologically the well-posedness of our model (1). Now, we discuss the existence of equilibria.

By simple computation system (1) has always one disease-free equilibrium of the form \(E_{f}(\frac{\lambda}{d},0,0)\). Hence, we define the basic reproduction number of our model as follows:

which can be rewritten as \(R_{0}=R_{01}+R_{02}\), where

From the biological point of view, the factor \(\frac{1}{u}\) is the average life expectancy of viruses, and \(\frac{1}{a+\rho}\) is the average life expectancy of infected cells, which is less than \(\frac{1}{a}\) because a part of infected cells returns to the uninfected state by loss of all cccDNA from their nucleus at a rate ρ. Since the viruses are produced by infected cells at a rate ky, \(\frac{k}{a+\rho}\) denotes the amount of viruses generated from living infected cell. Further, the number of susceptible cells at beginning of the infection is \(\frac{\lambda}{d}\), which means that \(f(\frac{\lambda}{d},0,0)\) and \(g(\frac{\lambda}{d},0)\) are the values of both incidence functions when all cells are uninfected. Therefore, \(R_{01}\) is the basic reproduction number corresponding to virus-to-cell infection mode, whereas \(R_{02}\) is the basic reproduction number corresponding to cell-to-cell transmission mode.

To find the other equilibrium of system (1), we solve the system

By (4) to (6) we obtain the equation

Since \(y=\frac{\lambda-dx}{a}\geq0\), we have \(x\leq\frac{\lambda }{d}\). Hence, there is no biological equilibrium when \(x>\frac{\lambda}{d}\). Define the function ψ on the interval \([0,\frac{\lambda}{d}]\) by

We have \(\psi(0)=-(a+\rho)u<0\), \(\psi(\frac{\lambda}{d})=(a+\rho )u(R_{0}-1)\), and

Hence, for \(R_{0}>1\), there exists a unique endemic equilibrium \(E^{*}(x^{*}, y^{*}, v^{*})\) with \(x^{*}\in(0, \frac{\lambda}{d})\), \(y^{*}>0\), and \(v^{*}>0\).

The previous discussions can be summarized in the following result.

Theorem 2.2

-

(i)

If \(R_{0} \leq1\), then system (1) has a unique disease-free equilibrium of the form \(E_{f}(\frac{\lambda}{d}, 0, 0)\).

-

(ii)

If \(R_{0}>1\), then the disease-free equilibrium is still present, and system (1) has a unique chronic infection equilibrium of the form \(E^{*}(x^{*}, y^{*}, v^{*})\) with \(x^{*}\in(0, \frac{\lambda}{d})\), \(y^{*}>0\), and \(v^{*}>0\).

3 Local stability

In this section, we discuss the local stability of both equilibria of system (1). Note that the Jacobian matrix of system (1) is given by

Firstly, we have the following result.

Theorem 3.1

The disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) is locally asymptotically stable if \(R_{0}<1\) and becomes unstable if \(R_{0}>1\).

Proof

Evaluating (8) at \(E_{f}\), we have

Clearly, the eigenvalues of the matrix \(J_{E_{f}}\) are

It is clear that \(\xi_{1}\) and \(\xi_{2}\) are negative. However, \(\xi _{3}\) is negative if \(R_{0}<1\) and is positive if \(R_{0}>1\). Therefore, \(E_{f}\) is locally asymptotically stable if \(R_{0}<1\) and unstable if \(R_{0}>1\). □

Next, we study the local stability of the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\). Note that the equilibrium \(E^{*}\) does not exist if \(R_{0}<1\) and \(E^{*}=E_{f}\) when \(R_{0}=1\).

Theorem 3.2

If \(R_{0}>1\), then the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) is locally asymptotically stable.

Proof

We assume that \(R_{0}>1\). Evaluating (8) at \(E^{*}\) and computing the characteristic equation about this point, we have

where

Since \(R_{0}>1\) and \(a+\rho-g(x^{*},y^{*})=\frac {kf(x^{*},y^{*},v^{*})}{u}>0\), we deduce that \(a_{1}\), \(a_{2}\), and \(a_{3}\) are positive. Furthermore,

From the Routh-Hurwitz theorem [22] we know that all roots of (9) have negative real parts. Thus, the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) is locally asymptotically stable for \(R_{0}>1\). □

4 Global stability

In this section, we investigate the global stability of the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) and the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\). For the global stability of \(E_{f}\), we assume that \(a\geq d\). Biologically, this assumption is often satisfied because a represents the death rate of infected cells and includes the possibility of death by bursting of infected cells. Further, this assumption is considered by many authors; see, for example, [23–25]. Therefore, we have the following result.

Theorem 4.1

If \(R_{0}\leq1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof

Construct the Lyapunov functional

Calculating the time derivative of \(V(t)\) along the positive solution of system (1), we have

Note that \(\limsup_{t\rightarrow\infty} x(t)\leq\frac {\lambda}{d}\). This yields that all omega limit points satisfy \(x(t)\leq\frac{\lambda}{d}\). Hence, it suffices to consider solutions for which \(x(t)\leq\frac{\lambda}{d}\). Using the expression of \(R_{0}\) given in (3), we get

Consequently, \(\dot{V}|_{\text{(1)}}\leq0\) for \(R_{0}\leq1\). Further, it is easy to show that the largest compact invariant set in \(\{(x,y,v)| \dot{V}=0\}\) is the singleton \(\{E_{f}\}\). By the LaSalle invariance principle [26], the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) is globally asymptotically stable for \(R_{0}\leq 1\). □

Now, we will investigate the global dynamics of system (1) when \(R_{0}>1\). Firstly, we need the following lemma.

Lemma 4.2

If \(R_{0}>1\), then system (1) is uniformly persistent.

Proof

This result follows from an application of Theorem 4.3 in [27] with \(X=\mathbb{R}^{3}\) and \(E=\Gamma\). The maximal invariant set M on the boundary ∂Γ is the singleton \(\{E_{f}\}\), and it is isolated. From Theorem 4.3 in [27] we can see that the uniform persistence of system (1) is equivalent to the instability of the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\). On the other hand, we have proved in Theorem 3.1 that \(E_{f}\) is unstable if \(R_{0}>1\). Thus, system (1) is uniformly persistent when \(R_{0}>1\). □

Next, we focus ourselves on the global stability of the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) by assuming that \(R_{0}>1\) and the incidence function f satisfies the following hypothesis:

Theorem 4.3

Assume that \(R_{0}>1\) and (H4) hold. Then the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof

To prove the global stability of \(E^{*}\), we will apply the geometrical approach developed by Li and Muldowney [28].

The second additive compound matrix of the Jacobian matrix J, given by (8), is defined by

where \(j_{kl}\) is the \((k,l)\)th entry of the matrix J.

We consider the matrix \(P=\operatorname{diag} (1,\frac{y}{v},\frac {y}{v})\). It follows then that

where the matrix \(P_{f}\) is obtained by replacing each entry \(p_{ij}\) of P by its derivative in the direction of solution of (1). Furthermore, we have

where

Define the norm in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\) as \(|(w_{1},w_{2},w_{3})|=\max\{ |w_{1}|,|w_{2}|+|w_{3}|\}\) for \((w_{1},w_{2},w_{3})\in\mathbb {R}^{3}\). Then the Lozinskii measure μ with respect to the norm \(|\cdot|\) can be estimated as follows (see [29]):

where \(g_{1}=\mu_{1}(B_{11})+|B_{12}|\) and \(g_{2}=|B_{21}|+\mu_{1}(B_{22})\). Here \(\mu_{1}\) denotes the Lozinskii measure with respect to the \(l_{1}\) vector norm, and \(|B_{12}|\) and \(|B_{21}|\) are matrix norms with respect to the \(l_{1}\) norm. Moreover, we have

Hence, we obtain

and

From Lemma 4.2 we know that system (1) is uniformly persistent when \(R_{0}>1\). Then there exists a compact absorbing set \(K\subset\Gamma\) [30]. Along each solution \((x(t),y(t),v(t) )\) of (1) with \(X_{0}= (x(0),y(0),v(0) )\in K\), we have

which implies that

Then, based on Theorem 3.5 of [28], we deduce that the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) is globally asymptotically stable. This completes the proof. □

5 Applications

The aim of this section is to apply our main results to some special cases of our model (1).

Example 1

Consider the system

where \(\beta_{1}\) is the infection rate by a free virus, and \(\beta _{2}\) is the infection rate by the cell-to-cell transmission. The other parameters in (14) have the same biological meanings as in model (1). The global dynamical behavior of this system was studied by Zhang et al. [21]. They proved that the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) is globally asymptotically stable if \(R_{0}<1\) and the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) is globally asymptotically stable when the condition \(1< R_{0}\leq1+\delta \) is satisfied, where \(\delta=\frac{\beta\lambda+(a-\rho)d+\sqrt{(\beta\lambda +(a-\rho)d)^{2}+4a\rho d^{2}}}{2\rho d}\). On the other hand, it is easy to verify that assumptions (H0)-(H4) hold for \(f(x,y,v)=\beta_{1}x\) and \(g(x,y)=\beta_{2}x\). By applying Theorems 3.1, 4.1, and 4.3 we obtain the following result, which improves the corresponding results in [21].

Corollary 5.1

-

(i)

If \(R_{0}\leq1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) of system (14) is globally asymptotically stable.

-

(ii)

If \(R_{0}>1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{f}\) becomes unstable, and the chronic infection equilibrium \(E^{*}\) of system (14) is globally asymptotically stable.

Example 2

Consider the system

which is a particular case of system (1) by letting

and \(g(x,y)=\frac{\beta_{2}x}{x+y}\), where \(\alpha_{0},\alpha _{1},\alpha_{2},\alpha_{3}\geq0\) are constants. Here, the incidence function for virus-to-cell infection mode includes six most common forms existing in the literature: the bilinear incidence (or mass action) when \(\alpha_{0}=1\) and \(\alpha_{1}=\alpha_{2}=\alpha_{3}=0\); the saturated incidence when \(\alpha_{0}=1\) and \(\alpha_{1}=\alpha_{3}=0\); the Beddington-DeAngelis functional response [31, 32] when \(\alpha_{0}=1\) and \(\alpha_{3}=0\); the Crowley-Martin functional response presented in [33] and used in [19] when \(\alpha_{0}=1\) and \(\alpha_{3}=\alpha_{1}\alpha_{2}\); the more generalized Hattaf functional response [34] when \(\alpha_{0}=1\); and the incidence function used by Zhuo in [35] in order to study the HBV infection with noncytolytic loss of infected cells when \(\alpha _{0}=\alpha_{3}=0\) and \(\alpha_{1}=\alpha_{2}=1\). However, the second incidence function for the cell-to-cell transmission mode was used by many authors (see, for example, [15, 36, 37]. Obviously, assumptions (H0)-(H3) hold, and we have

Therefore, assumption (H4) is satisfied. From Theorems 3.1, 4.1, and 4.3 we have the following result.

Corollary 5.2

References

Marsh, M, Helenius, A: Virus entry: open sesame. Cell 124, 729-740 (2006)

Mothes, W, Sherer, NM, Jin, J, Zhong, P: Virus cell-to-cell transmission. J. Virol. 84, 8360-8368 (2010)

Sattentau, Q: Avoiding the void: cell-to-cell spread of human viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 815-826 (2008)

Zhong, P, Agosto, LM, Munro, JB, Mothes, W: Cell-to-cell transmission of viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 44-50 (2013)

Guidotti, LG, Rochford, R, Chung, J, Shapiro, M, Purcell, R, Chisari, FV: Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science 284, 825-829 (1999)

Lewin, SR, Ribeiro, RM, Walters, T, Lau, GK, Bowden, S, Locarnini, S, Perelson, AS: Analysis of hepatitis B viral load decline under potent therapy: complex decay profiles observed. Hepatology 34, 101-1020 (2001)

Essunger, P, Perelson, AS: Modeling HIV infection of CD4+ T-cell subpopulations. J. Theor. Biol. 170, 367-391 (1994)

Hattaf, K, Yousfi, N, Tridane, A: Mathematical analysis of a virus dynamics model with general incidence rate and cure rate. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 13, 1866-1872 (2012)

Hattaf, K, Yousfi, N: A numerical method for a delayed viral infection model with general incidence rate. J. King Saud Univ., Sci. (2015). doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2015.10.003

Wang, X-Y, Hattaf, K, Huo, H-F, Xiang, H: Stability analysis of a delayed social epidemics model with general contact rate and its optimal control. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 12(4), 1267-1285 (2016)

Nowak, MA, Bangham, CRM: Population dynamics of immune responses to persistent viruses. Science 272, 74-79 (1996)

Nowak, MA, Bonhoeffer, S, Hill, AM, Boehme, R, Thomas, HC, McDade, H: Viral dynamics in hepatitis B virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 4398-4402 (1996)

Neumann, AU, Lam, NP, Dahari, H, Gretch, DR, Wiley, TE, Layden, TJ, Perelson, AS: Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-α therapy. Science 282, 103-107 (1998)

Perelson, AS: Modelling viral and immune system dynamics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 28-36 (2002)

Min, L, Su, Y, Kuang, Y: Mathematical analysis of a basic model of virus infection with application to HBV infection. Rocky Mt. J. Math. 38(5), 1573-1585 (2008)

Huang, G, Ma, W, Takeuchi, Y: Global properties for virus dynamics model with Beddington-DeAngelis functional response. Appl. Math. Lett. 22, 1690-1693 (2009)

Wang, K, Fan, A, Torres, A: Global properties of an improved hepatitis B virus model. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 11, 3131-3138 (2010)

Hattaf, K, Yousfi, N: Dynamics of HIV infection model with therapy and cure rate. Int. J. Tomogr. Stat. 16, 74-80 (2011)

Zhou, X, Cui, J: Global stability of the viral dynamics with Crowley-Martin functional response. Bull. Korean Math. Soc. 48(3), 555-574 (2011)

Bonhoeffer, S, Coffin, JM, Nowak, MA: Human immunodeficiency virus drug therapy and virus load. J. Virol. 71, 3275-3278 (1997)

Zhang, T, Meng, X, Zhang, T: Global dynamics of a virus dynamical model with cell-to-cell transmission and cure rate. Comput. Math. Methods Med. (2015). doi:10.1155/2015/758362

Gradshteyn, IS, Ryzhik, IM: Routh-Hurwitz theorem. In: Tables of Integrals, Series, and Products. Academic Press, San Diego (2000)

Srivastava, PK, Chandra, P: Modeling the dynamics of HIV and CD4+ T cells during primary infection. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 11, 612-618 (2010)

Pang, J, Cui, JA, Hui, J: The importance of immune responses in a model of hepatitis B virus. Nonlinear Dyn. 67(1), 723-734 (2012)

Wang, L, Li, MY: Mathematical analysis of the global dynamics of a model for HIV infection of CD4+ T cells. Math. Biosci. 200, 44-57 (2006)

LaSalle, JP: The Stability of Dynamical Systems. Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics. SIAM, Philadelphia (1976)

Freedman, H, Ruan, S, Tang, M: Uniform persistence and flows near a closed positively invariant set. J. Dyn. Differ. Equ. 6, 583-600 (1994)

Li, MY, Muldowney, JS: A geometric approach to the global-stability problems. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 27, 1070-1083 (1996)

Martin, RH Jr.: Logarithmic norms and projections applied to linear differential systems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 45, 432-454 (1974)

Butler, G, Waltman, P: Persistence in dynamical systems. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 98, 425-430 (1986)

Beddington, JR: Mutual interference between parasites or predators and its effect on searching efficiency. J. Anim. Ecol. 44, 331-341 (1975)

DeAngelis, DL, Goldsten, RA, Neill, R: A model for trophic interaction. Ecology 56, 881-892 (1975)

Crowley, PH, Martin, EK: Functional responses and interference within and between year classes of a dragonfly population. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 8, 211-221 (1989)

Hattaf, K, Yousfi, N, Tridane, A: Stability analysis of a virus dynamics model with general incidence rate and two delays. Appl. Math. Comput. 221, 514-521 (2013)

Zhuo, X: Analysis of a HBV infection model with non-cytolytic cure process. In: IEEE 6th International Conference on Systems Biology, pp. 148-151 (2012)

Yousfi, N, Hattaf, K, Tridane, A: Modeling the adaptative immune response in HBV infection. J. Math. Biol. 63, 933-957 (2011)

Wang, J, Tian, X: Global stability of a delay differential equation of hepatitis B virus infection with immune response. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2013, 94 (2013)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the editor and the anonymous referees for their constructive comments and suggestions, which have improved the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. They both read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hattaf, K., Yousfi, N. A generalized virus dynamics model with cell-to-cell transmission and cure rate. Adv Differ Equ 2016, 174 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0906-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0906-3