Abstract

In this paper, we consider a single population system with impulsively unilateral diffusion and impulsive input toxins in a polluted environment. All solutions of the investigated system are proved to be uniformly bounded. By mathematical analysis methods and the theory of impulsive differential equations, the condition of the globally asymptotically stable population-extinction solution of the investigated system is obtained. The permanent condition of the investigated system is also obtained. Finally, numerical analysis is carried out to illustrate our results. Our results provide a reliable theory basis for exploring biological resource management in a polluted environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Dispersal is a ubiquitous phenomenon in the natural world. It is important for us to understand the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of populations mirrored by the large number of mathematical models devoting to it in the scientific literature [1–5]. In recent years, the analysis of these models focus on the coexistence of population and local (or global) stability of equilibria [6, 7]. Spatial factors play a fundamental role on the persistence and stability of the population, and the complete results have not yet been obtained even in the simplest one-species case. Most previous papers focused on the population dynamical system modeled by the ordinary differential equations. But in practice, it is often the case that diffusion occurs in regular pulses. For example, when winter comes, birds will migrate between patches in search for a better environment, whereas they do not diffuse in other seasons, and the excursion of foliage seeds to occur at fixed periods of time every year, thus impulsive diffusion provides a more natural description. Jiao et al. [8] presented a delayed predator-prey model with impulsive diffusion between two patches. They obtained the permanent condition of the system by the theory of impulsive delay differential equation.

The most threatening problem to society is the change in both terrestrial and aquatic environment caused by the different kinds of stresses (temperature, toxicants/pollutants, etc.) affecting the long term survival of species, human life, and biodiversity of the habitat [9–11]. The presence of a toxicant in the environments decreases the growth rate of species and its carrying capacity. In recent years, some investigations have been carried out to study the effect of toxicant on a single species population [12–15], and a lot of scholars have adopted a mathematical modeling approach to study the influence of environmental pollution on the surviving of a biological population [16, 17]. Most of the previous work assumed that input of toxicant was continuous. The toxicants, however, are often emitted to the environment with regular pulse [18]. A lot of data have indicated that the use of agriculture chemicals may cause potential harm to the health of both human beings and other living beings. If the spraying of agriculture chemicals can be regarded as time pulse discharge, modeling by the continuous input of toxin can be regarded as obsolete and should be replaced by impulsive perturbations. In this case, though the discharge of toxin is transient, the influence of the toxin will last long. Therefore, it is very important how to control the pulse input cycle of toxin to protect the population’s persistent existence.

Theories of impulsive differential equations have been introduced into population dynamics lately [19–24]. Impulsive equations are found in almost every domain of applied science and have been studied in many investigations [19–33], they generally describe phenomena which are subject to steep or instantaneous changes. Especially, Jiao et al. [24] suggested releasing pesticides is combined with transmitting infective pests into an SI model. This may be accomplished by avoiding periods when the infective pests would be exposed or placing the pesticides in a location where the transmitting infective pests would not contact it. So we address an impulsive differential equation modeling the process of releasing infective pests and spraying pesticides at different fixed moments.

The organization of this paper is as follows. In the next section, we introduce the model and background concepts. In Section 3, some important lemmas are presented. In Section 4, we give the globally asymptotically stable condition of population-extinction solution of system (2.1) and the population permanent condition of system (2.1). In Section 5, a numerical analysis and a brief discussion are given.

2 The model

In this work, we consider a single population system with impulsively unilateral diffusion and impulsive input toxins in a polluted environment,

where we suppose that system (2.1) is composed of two patches connected by diffusion. Patch 1 is occupied by population \(x(t)\). Patch 2 is occupied by population \(y(t)\). \(x(t)\) represents the density of the population at patch 1, and \(y(t)\) represents the density of the population at patch 2. Patch 1 is polluted periodically. There is no pollution in patch 2. \(c_{o}(t)\) represents the concentration of toxicant in the organism of the population at time t in patch 1. \(c_{e}(t)\) represents the concentration of the toxicant in the system environment of patch 1. The intrinsic rate of natural increase and density dependence rate of the population in the first habitat are denoted by a, b, respectively. \(a/b\) denotes the carrying capacity of population in the patch 1. \(d>0\) represents the death rate of the population in patch 2. \(fc_{e}(t)\) is the organism’s net uptake of toxicant from the system environment at time t in patch 1. \(-g c_{0}(t)\) and \(-mc_{0}(t)\) represent the elimination and depuration rates of toxicant in the organism at time t in patch 1, respectively. \(-h c_{e}(t)\) represents the totality of losses from the system environment including processes such as biological transformation, chemical hydrolysis, volatilization, microbial degradation, and photosynthetic degradation at time t in patch 1, and \(h>f\) is assumed in this paper. \(\beta>0\) represents the depletion rate coefficient of the normal population during to the environment pollutant concentration of patch 1. The impulsive inputting toxicant occurs every τ period (τ is a positive constant)in patch 1. \(\triangle c_{e}(t)=c_{e}(t^{+})-c_{e}(t)\). \(\mu\geq0 \) represents the amount of the pulse input of toxicant concentration at \(t=(n+l)\tau\), \(0< l<1\), \(n\in Z_{+}\) in patch 1. D is the dispersal rate between the two patches. It is assumed that the net exchange from patch 1 to patch 2 is proportional to the pollution degree of patch 1. The pulse diffusion occurs every τ period (τ is a positive constant), the system evolves from its initial state without being further affected by diffusion until the next pulse appears, where \(\triangle x(n\tau)=x(n\tau^{+})-x(n\tau)\). \(x(n\tau^{+})\) represents the density of the population in patch 1 immediately after the nth diffusion pulse at time \(t = n\tau\), while \(x(n\tau)\) represents the density of the population in patch 1 before the nth diffusion pulse at time \(t = n\tau\), \(n = 0, 1, 2,\ldots\) .

In this paper, we always assume that

-

(A1)

the population diffuses periodically from patch 1 to patch 2 for dodging polluted environment in patch 1;

-

(A2)

the toxicants are emitted to the environment with regular pulse in patch 1, and patch 2 has no pollution.

3 Preliminary lemmas

Before discussing the main results, we will give some definitions, notations, and lemmas. Denote by \(f=(f_{1},f_{2},f_{3},f_{4})\) the map defined by the right hand of system (2.1). The solution of system (2.1), denoted by \(z(t)=(x(t),y(t),c_{o}(t), c_{e}(t))^{T}\), is a piecewise continuous function z: \(R_{+}\rightarrow R_{+}^{4}\), where \(R_{+}=[0,\infty)\), \(R_{+}^{4}=\{z\in R^{4}:z>0\}\). \(z(t)\) is continuous on \((n\tau, (n+l)\tau]\) and \(((n+l)\tau, (n+1)\tau]\) (\(n \in Z_{+}\), \(0 \leq l \leq1\)). According to [21], the global existence and uniqueness of solutions of system (2.1) is guaranteed by the smoothness properties of f, which denotes the mapping defined by the right-hand side of system (2.1).

Let \(V:R_{+}\times R_{+}^{4} \rightarrow R_{+}\), then V is said to belong to class \(V_{0}\), if

-

(i)

V is continuous in \((n\tau, (n+l)\tau]\times R^{4}_{+}\) and \(((n+l)\tau, (n+1)\tau]\times R^{4}_{+}\), for each \(z\in R^{4}_{+}\), \(n \in Z_{+}\). \(\lim_{(t, u)\rightarrow((n+l)\tau^{+}, z)}V(t,u)=V((n+l)\tau^{+}, z)\), and \(\lim_{(t,u)\rightarrow ((n+1)\tau^{+}, z)}V(t, u)=V((n+1)\tau^{+}, z)\) exist;

-

(ii)

V is locally \(Lipschitzian\) in z.

Definition 3.1

If \(V \in V_{0} \), then for \((t, z) \in(n \tau, (n+l)\tau]\times R^{4}_{+}\) and \(((n+l)\tau, (n+1)\tau]\times R^{4}_{+}\), the upper right derivative of \(V(t,z)\) with respect to the impulsive differential system (2.1) is defined as

Now, we show that all solutions of system (2.1) are uniformly ultimately bounded.

Lemma 3.2

There exists a constant \(M>0\) such that \(x(t)\leq M\), \(y(t)\leq M\) and \(c_{o}(t)\leq M\), \(c_{e}(t)\leq M\) for each solution \((x(t),y(t),c_{o}(t),c_{e}(t) )\) of system (2.1) with all t large enough.

Proof

Define \(V(t)=x(t)+y(t)+c_{o}(t)+c_{e}(t)\), and choose \(\lambda =\min\{d,g+m,h-f\}\), then \(t\neq n\tau\), we have

For convenience, we denote \(\zeta=\frac{(a+\lambda)^{2}}{4b}\).

When \(t=(n+l)\tau\),

When \(t=(n+1)\tau\),

From Lemma 2.2 [22], page 23, for \(t\in(n\tau,(n+l)\tau]\) and \(((n+l)\tau,(n+1)\tau]\), we have

So \(V(t)\) is uniformly ultimately bounded. Hence, by the definition of \(V(t)\), there exists a constant \(M>0\) such that \(x(t)\leq M\), \(y(t)\leq M\), \(c_{o}(t)\leq M\), and \(c_{e}(t)\leq M\) for t large enough. The proof is complete. □

The subsystem of (2.1) is

Then we give an important property of system (3.1) as follows.

Lemma 3.3

[33]

System (3.1) has a unique positive τ-periodic solution \((\widetilde{c_{o}(t)},\widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\), which is globally asymptotically stable, where

Remark 3.4

From Lemma 3.3, we can obtain \(m_{o}-\varepsilon\leq c_{o}(t)\leq M_{o}+\varepsilon\) and \(m_{e}-\varepsilon\leq c_{e}(t)\leq M_{e}+\varepsilon\) for t large enough, where \(m_{o}=\frac{\mu f(e^{-(g+m)\tau}-e^{-h\tau})}{(h-g-m)(e^{(g+m)\tau}-1)(1-e^{-h\tau})}>0\), \(M_{o}=\frac{\mu f(e^{-(g+m)\tau}-e^{-h\tau})}{(h-g-m)(1-e^{-(g+m)\tau})(1-e^{-h\tau })}+\frac{\mu f}{\vert h-g-m\vert (1-e^{-h\tau})}>0\), \(m_{e}=\frac{\mu e^{-h\tau}}{1-e^{-h\tau}}>0\) and \(M_{e}=\frac{\mu}{1-e^{-h\tau}}>0\) for a sufficiently small \(\varepsilon>0\).

4 The dynamics

In this section, we firstly prove that system (2.1) is permanent. For system (2.1) obviously exists a population-extinction boundary periodic solution \((0,0,\widetilde {c_{o}(t)},\widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\). Then we prove that the population-extinction boundary periodic solution \((0,0,\widetilde{c_{o}(t)}, \widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\) of system (2.1) is globally asymptotically stable.

4.1 The permanence of (2.1)

The subsystem of system (2.1) is obtained as follows:

Considering the first equation of system (4.1) and Remark 3.4, we have

Then we can obtain two comparative systems, referring to system (4.1),

and

It is clear that

We can easily obtain the analytic solution of system (4.3) between pulses, i.e.

Considering the third and fourth equations of system (4.3), we have the stroboscopic map of system (4.3),

The two fixed points of (4.7) are obtained as \(G_{1}(0,0)\) and \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast},y_{1}^{\ast})\), where

Theorem 4.1

-

(i)

If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}< a-\beta M_{o}\), the fixed point \(G_{1}(0,0)\) of (4.7) is globally asymptotically stable.

-

(ii)

If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}>a-\beta M_{o}\), the fixed point \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast}, y_{1}^{\ast})\) of (4.7) is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof

For convenience, we denote \((x_{1}^{n+l},y_{1}^{n+l})=(x_{1}((n+l)\tau^{+}),y_{1}((n+l)\tau^{+}))\). The linear form of (4.7) can be written as

Obviously, the near dynamics of \(G_{1}(0,0)\) and \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast}, y_{1}^{\ast})\) are determined by the linear system (4.7). The stabilities of \(G_{1}(0,0)\) and \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast}, y_{1}^{\ast})\) of (4.7) are determined by the eigenvalue of M being less than 1. If M satisfies the \(Jury\) criteria [30], we can know the eigenvalue of M less than 1, we have

(i) If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}< a-\beta M_{o}\), there must exist a sufficiently small \(\varepsilon>0\) such that \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))\tau}< a-\beta (M_{o}+\varepsilon)\), and \(\varepsilon<\frac{a-\beta M_{o}}{\beta}\). Then \(G_{1}(0,0)\) is the unique fixed point of system (4.7), we have

Then

From the \(Jury\) criteria, \(G_{1}(0,0)\) is locally stable, then it is globally asymptotically stable.

(ii) If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}>a-\beta M_{o}\), there must exist a sufficiently small \(\varepsilon>0\) such that \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))\tau}>a-\beta (M_{o}+\varepsilon)\), Then \(G_{1}(0,0)\) is unstable. \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast},y_{1}^{\ast})\) exists, and

where \(A=ae^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))\tau}\), \(B=a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon)\), \(C=b[e^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))\tau}-1]\), \(E=e^{-d\tau}\), and \(1< E<1\).

Then

and from the \(Jury\) criteria, \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast}, y_{1}^{\ast})\) is locally stable, and then it is globally asymptotically stable. This completes the proof. □

Similarly to the methods in [32], the following lemma can easily be proved.

Theorem 4.2

-

(i)

If

$$(1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}< a-\beta M_{o}, $$the triviality periodic solution \((0,0)\) of system (4.3) is globally asymptotically stable.

-

(ii)

If

$$(1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}>a-\beta M_{o}, $$the periodic solution \((\widetilde{x_{1}(t)},\widetilde{y_{1}(t)} )\) of system (4.3) is globally asymptotically stable, where

$$ \textstyle\begin{cases} \widetilde{x_{1}(t)}=\frac{ae^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))(t-(n+l)\tau )}x_{1}^{\ast}}{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon)) +b[e^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))(t-(n+l)\tau)}-1]x_{1}^{\ast}}, &(n+l)\tau< t\leq(n+l+1)\tau,\\ \widetilde{ y_{1}(t)}=y_{1}^{\ast}e^{-d(t-(n+l)\tau)}, &(n+l)\tau< t\leq(n+l+1)\tau, \end{cases} $$(4.13)where \(x_{1}^{\ast}\) and \(y_{1}^{\ast}\) are determined as in (4.8).

From Theorem 4.2, we can obtain the following.

Remark 4.3

If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}>a-\beta M_{o}\), for any sufficiently small \(\varepsilon_{1}>0\), there exists a \(T_{1}\) such that \(x_{1}(t)\geq \widetilde{x_{1}(t)}-\varepsilon_{1}\) and \(y_{1}(t)\geq \widetilde{y_{1}(t)}-\varepsilon_{1}\) for \(t>T_{1}\).

We can also obtain the analytic solution of system (4.4) between pulses, i.e.

Considering the third and fourth equations of system (4.3), we have the stroboscopic map of system (4.3),

The two fixed points of (4.7) are obtained as \(G_{1}(0,0)\) and \(G_{2}(x_{1}^{\ast},y_{1}^{\ast})\), where

Similarly to system (4.3), we have some theorems as regards system (4.4).

Theorem 4.4

-

(i)

If

$$(1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))\tau}< a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon), $$the fixed point \(G'_{1}(0,0)\) of (4.15) is globally asymptotically stable.

-

(ii)

If

$$(1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))\tau}>a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon), $$the fixed point \(G'_{2}(x_{2}^{\ast}, y_{2}^{\ast})\) of (4.15) is globally asymptotically stable.

Theorem 4.5

-

(i)

If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))\tau}< a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon )\), the triviality periodic solution \((0,0)\) of system (4.4) is globally asymptotically stable.

-

(ii)

If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))\tau}>a-\beta (m_{o}-\varepsilon)\) the periodic solution \((\widetilde{x_{2}(t)},\widetilde{y_{2}(t)} )\) of system (4.4) is globally asymptotically stable, where

$$ \textstyle\begin{cases} \widetilde{x_{2}(t)}=\frac{ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))(t-(n+l)\tau )}x_{2}^{\ast}}{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon)) +b[e^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))(t-(n+l)\tau)}-1]x_{2}^{\ast}},& (n+l)\tau< t\leq(n+l+1)\tau,\\ \widetilde{y_{2}(t)}=y_{2}^{\ast}e^{-d(t-(n+l)\tau)}, &(n+l)\tau< t\leq(n+l+1)\tau. \end{cases} $$(4.17)Here \(x_{2}^{\ast}\) and \(y_{2}^{\ast}\) are determined as in (4.16).

Remark 4.6

If \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))\tau}< a-\beta (m_{o}-\varepsilon)\), for any sufficiently small \(\varepsilon_{2}>0\), there exists a \(T_{2}\) such that \(x_{2}(t)\leq \varepsilon_{2}\) and \(y_{2}(t)\leq \varepsilon_{2}\) for \(t>T_{2}\).

From Theorem 4.2, Remark 4.3, Theorem 4.5, and Remark 4.6, we present an important theorem in this paper.

Theorem 4.7

-

(i)

If

$$(1-D)ae^{(a-\beta m_{o})\tau}< a-\beta m_{o} $$holds, the population of system (2.1) will go extinct.

-

(ii)

If

$$(1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}>a-\beta M_{o} $$holds, the population of system (2.1) is permanent.

Proof

(i) According to the impulsive comparative theorem [18] and the condition \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta m_{o})\tau}< a-\beta m_{o}\), there exists a sufficiently small \(\varepsilon>0\) such that \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon))\tau}< a-\beta(m_{o}-\varepsilon )\), and, from Remark 4.6, for any sufficiently small \(\varepsilon_{2}>0\), there exists a \(T_{2}>0\) such that \(x(t)\leq x_{2}(t)\leq\varepsilon_{2}\) and \(y(t)\leq y_{2}(t)\leq \varepsilon_{2}\) for \(t>T_{2}\). That is to say, for any sufficiently small \(\varepsilon_{2}>0\), there exists a \(T_{2}>0\) such that \(x(t)\leq\varepsilon_{2}\) and \(y(t)\leq\varepsilon_{2}\) for \(t>T_{2}\). These show that the population of system (2.1) will go extinct.

(ii) According to the impulsive comparative theorem [18] and the condition \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta M_{o})\tau}>a-\beta M_{o}\), there exists a sufficiently small \(\varepsilon>0\) such that \((1-D)ae^{(a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon))\tau}>a-\beta(M_{o}+\varepsilon )\), and from Remark 4.3, for any sufficiently small \(\varepsilon_{1}>0\), there exists a \(T_{1}>0\) such that \(x(t)\geq x_{1}(t)\geq\widetilde{x_{1}(t)}-\varepsilon_{1}\geq x_{1}^{\ast}e^{-(d_{1}+M_{o}+\varepsilon)\tau}-\varepsilon_{1}\stackrel {\Delta}{=}m_{1}\) and \(y(t)\geq y_{1}(t)\geq\widetilde{y_{1}(t)}-\varepsilon_{1}\geq y_{1}^{\ast}e^{-d_{2}\tau}-\varepsilon_{1}\stackrel{\Delta}{=}m_{2}\) for \(t>T_{1}\), where \(x^{\ast}_{1}\) and \(y^{\ast}_{1}\) are determined as (4.8). From Lemma 3.2, there exist \(M>0\) and \(T>0\) such that \(x(t)< M\) and \(y(t)< M\) for \(t>T\). From the above discussion, we know \(m_{1}< x(t)< M\) and \(m_{2}< y(t)< M\) for \(t>\max\{T,T_{1}\}\). That is to say, the population of system (2.1) is permanent. □

From Lemma 3.2, Remark 3.4, and Theorem 4.7, we have the following.

Theorem 4.8

If

system (2.1) is permanent.

4.2 The globally asymptotical stability of population-extinction boundary periodic solution of (2.1)

Theorem 4.9

If

holds, the population-extinction boundary periodic solution \((0,0,\widetilde{c_{o}(t)}, \widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\) of system (2.1) is globally asymptotically stable, where \(m_{o}\) is defined as Remark 3.4.

Proof

Firstly, we prove the local stability. Define \(x(t)=x(t)\), \(y(t)=y(t)\), \(z_{1}(t)=c_{o}(t)-\widetilde{c_{o}(t)}\), \(z_{2}(t)=c_{e}(t)-\widetilde {c_{e}(t)}\), we have the following linearly similar system of system (2.1):

It is easy to obtain the fundamental solution matrix

There is no need to calculate the exact form of † as it is not required in the analysis that follows. The linearization of the 5th, 6th, 18th, and 9th equations of system (2.1) is

The linearization of the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th equations of system (2.1) is

The stability of the population-extinction periodic solution \((0,0,\widetilde{c_{o}(t)},\widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\) is determined by the eigenvalues of

which are

and

According the condition, we easily find \((1-D)e^{(a-\beta m_{o})\tau }<1\). Then, from Remark 3.4, we have \((1-D)\exp(\int^{\tau }_{0}(a-\beta\widetilde{c_{o}(s)})\,ds)<1\), then \(\lambda_{1}<1\). From the Floquet theory [18], the population-extinction \((0,0,\widetilde{c_{o}(t)},\widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\) is locally stable.

The following task is to prove the global attraction. Then we have subsystem (3.1) of system (2.1). From Lemma 3.3, we know that the τ-periodic solution \((\widetilde{c_{o}(t)},\widetilde{c_{e}(t)})\) of system (2.1) has globally asymptotical stability, and

for all t large enough. For convenience, we may assume (4.2) holds for all \(t\geq0\). From (2.1) and (4.2), we get

and its comparable equation is system (4.4). From Remark 4.6, for any sufficiently small \(\varepsilon_{2}>0\), there exists a \(T_{2}\) such that \(x(t)\leq x_{2}(t)\leq \varepsilon_{2}\) and \(y(t)\leq y_{2}(t)\leq \varepsilon_{2}\) for \(t>T_{2}\). That is, as \(t\rightarrow\infty\), we have

This completes the proof. □

5 Discussion

In this work, we consider a single population system with impulsively unilateral diffusion and impulsive input toxins in a polluted environment. We prove that all solutions of system (2.1) are uniformly ultimately bounded. The condition of the globally asymptotically stable population-extinction solution of system (2.1) is obtained, and the condition of the population permanence of system (2.1) is also obtained.

5.1 The simulation of system (2.1) affected by parameter μ

If it is assumed that \(x(0)=1\), \(y(0)=0.5\), \(c_{o}(0)=0.5\), \(c_{e}(0)=0.5\), \(a=0.4\), \(b=1\), \(d=0.1\), \(\beta=0.05\), \(\mu=2\), \(f=0.1\), \(m=0.1\), \(g=0.1\), \(l=0.25\), \(D=0.1\), \(\tau=1\), then the population-extinction periodic solution of system (2.1) is globally asymptotically stable (see Figure 1). If it is also assumed that \(x(0)=1\), \(y(0)=0.5\), \(c_{o}(0)=0.5\), \(c_{e}(0)=0.5\), \(a=0.4\), \(b=1\), \(d=0.1\), \(\beta =0.05\), \(\mu=1\), \(f=0.1\), \(m=0.1\), \(g=0.1\), \(l=0.25\), \(D=0.1\), \(\tau=1\), then system (2.1) is permanent (see Figure 2).

Globally asymptotically stable population-extinction periodic solution of system ( 2.1 ) with \(\pmb{x(0)=1}\) , \(\pmb{y(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{o}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{e}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{a=0.4}\) , \(\pmb{b=1}\) , \(\pmb{d=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\beta=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=2}\) , \(\pmb{f=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{m=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{g=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{l=0.25}\) , \(\pmb{D=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\tau=1}\) . (a) Time-series of \(x(t)\); (b) time-series of \(y(t)\); (c) time-series of \(c_{o}(t)\); (d) time-series of \(c_{e}(t)\).

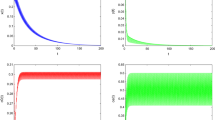

The permanence of system ( 2.1 ) with \(\pmb{x(0)=1}\) , \(\pmb{y(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{o}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{e}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{a=0.4}\) , \(\pmb{b=1}\) , \(\pmb{d=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\beta=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=1}\) , \(\pmb{f=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{m=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{g=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{l=0.25}\) , \(\pmb{D=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\tau=1}\) . (e) Time-series of \(x(t)\); (f) time-series of \(y(t)\); (g) time-series of \(c_{o}(t)\); (h) time-series of \(c_{e}(t)\).

From the simulation experiments, the parameters μ obviously affect the dynamical behaviors of system (2.1). If all parameters of system (2.1) are fixed, when \(\mu=2\), the population of system (2.1) will go extinct, when \(\mu=1\), system (2.1) is permanent. From Theorem 4.7, we can easily deduce that there must exist a threshold \(\mu^{\ast}\). If \(\mu >\mu^{\ast}\), the population-extinction periodic solution of system (2.1) is globally asymptotically stable. If \(\mu<\mu^{\ast}\), system (2.1) is permanent.

5.2 The simulation of system (2.1) affected by parameter D

If it is assumed that \(x(0)=1\), \(y(0)=0.5\), \(c_{o}(0)=0.5\), \(c_{e}(0)=0.5\), \(a=0.4\), \(b=1\), \(d=0.1\), \(\beta=0.05\), \(\mu=1\), \(f=0.1\), \(m=0.1\), \(g=0.1\), \(l=0.25\), \(D=0.95\), \(\tau=1\), then the population-extinction periodic solution of system (2.1) is globally asymptotically stable (see Figure 3). If it is also assumed that \(x(0)=1\), \(y(0)=0.5\), \(c_{o}(0)=0.5\), \(c_{e}(0)=0.5\), \(a=0.4\), \(b=1\), \(d=0.1\), \(\beta =0.05\), \(\mu=1\), \(f=0.1\), \(m=0.1\), \(g=0.1\), \(l=0.25\), \(D=0.1\), \(\tau=1\), then system (2.1) is permanent (see Figure 4).

Globally asymptotically stable population-extinction periodic solution of system ( 2.1 ) with \(\pmb{x(0)=1}\) , \(\pmb{y(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{o}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{e}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{a=0.4}\) , \(\pmb{b=1}\) , \(\pmb{d=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\beta=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=1}\) , \(\pmb{f=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{m=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{g=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{l=0.25}\) , \(\pmb{D=0.95}\) , \(\pmb{\tau=1}\) . (a \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) Time-series of \(x(t)\); (b \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) time-series of \(y(t)\); (c \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) time-series of \(c_{o}(t)\); (d \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) time-series of \(c_{e}(t)\).

The permanence of system ( 2.1 ) with \(\pmb{x(0)=1}\) , \(\pmb{y(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{o}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{c_{e}(0)=0.5}\) , \(\pmb{a=0.4}\) , \(\pmb{b=1}\) , \(\pmb{d=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\beta=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=1}\) , \(\pmb{f=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{m=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{g=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{l=0.25}\) , \(\pmb{D=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\tau=1}\) . (e \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) Time-series of \(x(t)\); (f \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) time-series of \(y(t)\); (g \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) time-series of \(c_{o}(t)\); (h \(\boldsymbol{'}\) ) time-series of \(c_{e}(t)\).

From the simulation experiments, the parameters D obviously affect the dynamical behaviors of system (2.1). If all parameters of system (2.1) are fixed, when \(D=0.95\), the population of system (2.1) will go extinct, when \(D=0.1\), system (2.1) is permanent. From Theorem 4.7, we can easily deduce that there must exist a threshold \(D^{\ast}\). If \(D >D^{\ast}\), the population-extinction periodic solution of system (2.1) is globally asymptotically stable. If \(D < D^{\ast}\), system (2.1) is permanent.

From the simulations of system (2.1), the diffusing parameter D of the population plays an important role in system (2.1). The environmental pollution will also reduce the biological diversity of the nature world. Our results also provide a reliable tactic basis for practical biological resource management.

References

Beretta, E, Solimano, F: Global stability and periodic orbits for two patch predator-prey diffusion delay models. Math. Biosci. 85, 153-183 (1987)

Cui, JA, Chen, LS: Permanence and extinction in logistic and Lotka-Volterra system with diffusion. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 258(2), 512-535 (2001)

Freedman, HI: Single species migration in two habitats: persistence and extinction. Math. Model. 8, 778-780 (1987)

Freedman, HI, Takeuchi, Y: Global stability and predator dynamics in a model of prey dispersal in a patchy environment. Nonlinear Anal. 13, 993-1002 (1989)

Freedman, HI, Takeuchi, Y: Predator survival versus extinction as a function of dispersal in a predator-prey model with patchy environment. Appl. Anal. 31, 247-266 (1989)

Allen, LJS: Persistence and extinction in single-species reaction-diffusion models. Bull. Math. Biol. 45(2), 209-227 (1983)

Beretta, E, Takeuchi, Y: Global stability of single species diffusion Volterra models with continuous time delays. Bull. Math. Biol. 49, 431-448 (1987)

Jiao, JJ, Yang, XS, Cai, SH, Chen, LS: Dynamical analysis of a delayed predator-prey model with impulsive diffusion between two patches. Math. Comput. Simul. 80, 522-532 (2009)

Hass, CN: Application of predator-prey models to disinfection. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 53, 378-386 (1981)

Hsu, SB, Waltman, P: Competition in the chemostat when one competitor produces a toxin. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 15, 471-490 (1998)

Jenson, AL, Marshall, JS: Application of surplus production model to access environmental impacts in exploited populations of Daphnia pulex in the laboratory. Environ. Pollut. A 28, 273-280 (1982)

De Luna, JT, Hallam, TG: Effects of toxicants on population: a qualitative approach IV. Resource-consumer-toxicants model. Ecol. Model. 35, 249-273 (1987)

Dubey, B: Modelling the effect of toxicant on forestry resources. Indian J. Pure Appl. Math. 28, 1-12 (1997)

Freedman, HI, Shukla, JB: Models for the effect of toxicant in a single-species and predator-prey systems. J. Math. Biol. 30, 15-30 (1991)

Hallam, TG, Clark, CE, Jordan, GS: Effects of toxicant on population: a qualitative approach II. First order kinetics. J. Math. Biol. 18, 25-37 (1983)

Zhang, BG: Population’s Ecological Mathematics Modeling. Publishing of Qingdao Marine University, Qingdao (1990)

Hallam, TG, Clark, CE, Lassider, RR: Effects of toxicant on population: a qualitative approach I. Equilibrium environmental exposure. Ecol. Model. 18, 291-340 (1983)

Liu, B, Chen, LS, Zhang, YJ: The effects of impulsive toxicant input on a population in a polluted environment. J. Biol. Syst. 11, 265-287 (2003)

Liu, XN: Impulsive stabilization and applications to population growth models. J. Math. 25(1), 381-395 (1995)

Lakshmikantham, V: Theory of Impulsive Differential Equations. World Scientific, Singapore (1989)

Liu, XN, Chen, LS: Complex dynamics of Holling type II Lotka-Volterra predator-prey system with impulsive perturbations on the predator. Chaos Solitons Fractals 16, 311-320 (2003)

Song, XY, Chen, LS: Uniform persistence and global attractivity for nonautonomous competitive systems with dispersion. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 15, 307-314 (2002)

Meng, XZ, Chen, LS: Permanence and global stability in an impulsive Lotka-Volterra N-species competitive system with both discrete delays and continuous delays. Int. J. Biomath. 1(2), 179-196 (2008)

Jiao, JJ, et al.: An appropriate pest management SI model with biological and chemical control concern. Appl. Math. Comput. 196, 285-293 (2008)

Murray, JD: Mathematical Biology, 2nd edn. Springer, Heidelberg (1993)

Takeuchi, Y: Global Dynamical Properties of Lotka-Volterra Systems. World Scientific, Singapore (1996)

Takeuchi, Y, Oshime, Y, Matsuda, H: Persistence and periodic orbits of a three-competitor model with refuges. Math. Biosci. 108(1), 105-125 (1992)

Kuang, Y: Delay Differential Equation with Application in Population Dynamics, pp. 67-70. Academic Press, New York (1987)

Leung, AW: Optimal harvesting-coefficient control of stead-state prey-predator diffusive Volterra-Lotka system. Appl. Math. Optim. 31, 219-241 (1995)

Alvarez, HR, Shepp, LA: Optimal harvesting of stochastically fluctuating populations. J. Math. Biol. 37, 155-177 (1998)

Tang, SY, Chen, LS: The effect of seasonal harvesting on stage-structured population models. J. Math. Biol. 48, 357-374 (2003)

Zhao, Z, Chen, LS: The effect of pulsed harvesting policy on the inshore-offshore fishery model with impulsive diffusion. Nonlinear Dyn. 63, 521-535 (2011)

Jiao, JJ, Ye, KL, Chen, LS: Dynamical analysis of a five-dimensioned chemostat model with impulsive diffusion and pulse input environmental toxicant. Chaos Solitons Fractals 44, 17-27 (2011)

Acknowledgements

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (11361014, 10961008), the Science Technology Foundation of Guizhou Education Department (2008038), and the Science Technology Foundation of Guizhou (2010J2130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SH carried out the main part of this article, JJ corrected the manuscript, LM brought forward some suggestions on this article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, S., Jiao, J. & Li, L. Dynamics of a single population system with impulsively unilateral diffusion and impulsive input toxins in polluted environment. Adv Differ Equ 2015, 308 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0600-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0600-x