Abstract

In this paper, we present the global dynamics of an SEIRS epidemic model for an infectious disease not containing the permanent acquired immunity with non-linear generalized incidence rate and preventive vaccination. The model exhibits two equilibria: the disease-free and endemic equilibrium. The disease-free equilibrium is stable locally as well as globally when the basic reproduction number \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}<1\) and an unstable equilibrium occurs for \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\). Moreover, the endemic equilibrium is stable both locally and globally when \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\). We show the global stability of an endemic equilibrium by a geometric approach. Further, numerical results are presented to validate the theoretical results. Finally, we conclude our work with a brief discussion.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

To reduce the spread and increase control of an infectious disease the quarantine and vaccination methods are used commonly. For a cost effective strategy and successful intervention policy, vaccination is often considered the best tool for eradication of the morbidity and mortality of people. For the diseases measles, rubella, diphtheria, mumps, influenza, tetanus, and hepatitis B, it has been used to tackle them. In some cases for a vaccinated person it is not necessary to have life-long immunity; see [1, 2]. In a certain community it is sometimes very difficult or impossible to vaccinate the susceptible individuals. The main reason behind this is the unavailability (or not easy availability) of such vaccine in those countries. So, it is reasonable to obtain a fraction of immune individuals in the community for which the disease does not become epidemic; that fraction is known as the herd immunity threshold [1].

A variety of incidence rates have been used in the literature, for instance, [2–6]. In all these models the incidence rate has been considered as a law of mass action. For the communicable diseases, the incidence rate in the form of \(\beta S I\) is used, where β shows the per capita contact rate. For the first time [7] introduced a saturated incidence after the cholera epidemic in Bari in 1937. This reference used the incidence rate in the form of \(Sg(I)\). Muroya et al. [8] presented a SIRS epidemic with graded curve and incomplete recovery rates. The global dynamics is completely described by the basic reproduction number \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}\). Denphedtnong et al. [9] proposed a SEIRS mathematical model with transport related infection. According to this reference, the transportation among cities is one of the main factors to affect the outbreak of diseases. A SEIRS mathematical model for disease transmission incorporating the immigration of infected, susceptible, and exposed persons is analyzed by [10]. A delay SEIRS epidemic model for computer virus network is studied by [11]. The effect of behavioral changes for the susceptible individuals have been incorporated by Liu et al. [12] in this model. They used the incidence rate in the form \(\frac{\beta SI^{p}}{1+kI^{q}}\), where k is negative constant, while p and q are positive. Different cases have been studied for p, q, and k; see, for example [7, 13–15].

In mathematical models the global stability is very important. Many methods have been used in the literature to obtain the global stability for the epidemic models. For example, [16] used the second Lyapunov function in his model. In population biology models, the Lyapunov function candidate is used as a Volterra function \((y-y^{*}-y^{*}\ln\frac{y}{y^{*}})\). Beretta and Capasso used this function in [17] and also the authors used [4, 7, 18–26] for the global stability of epidemic models. In this work, we modified the model of [22], to incorporate the exposed class. This new class is very important, because many infectious diseases like, dengue, yellow fever, hepatitis B, etc., have a specific incubation period. For this reason, the analysis of the exposed class is very important.

Based on the above motivation, the present paper studies the global dynamics of a SEIRS epidemic model with non-linear generalized incidences and preventive vaccination. The structure of the paper is as follows: We formulate the basic problem, with their properties in Section 2. In Section 3, we find the local stability of disease free and endemic equilibrium. The global stability of both the disease-free and the endemic equilibrium discussed in Section 4. Numerical results with a brief discussion are presented in Section 5.

2 Model formulation

In this section, we formulate the basic model by dividing the population into four sub-classes, \(S(t)\), the susceptible, \(E(t)\), the exposed (not yet infectious), \(I(t)\), the infected and \(R(t)\), the recovered or removed individuals. We denote the total population size of the individuals by \(N(t)\), with \(N(t)=S(t)+E(t)+I(t)+R(t)\). The transition diagram is presented in Figure 1. The governing model is given as follows:

subject to the initial conditions

The parameters with their description are shown in Table 1.

We assumed the same transmission rate in the form of \(\frac{\beta S I}{\psi(I)}\), where ψ is a positive function with \(\psi(0)=1\) and \(\psi'\geq0\), as used by [22]. This is the generalization of mass action incidences, that is, \(\psi(I)=1\), and the incidence rate \(\frac{\beta S I}{1+kI^{q}}\). For small I, the function \(\frac{I}{\psi(I)}\) is increasing, while it is decreasing for large I, that is \(\psi(I)=1+I^{2}\). This shows the ‘psychological’ effect: when the number of infective individuals is high, the increase in the number of infectives varies inversely to the force of infection, due to the presence of the large number of infectives in the population, which then tends to decrease the individuals’ contacts per unit time [7, 15].

2.1 Basic properties of the model

In this subsection, we investigate the basic reproduction number and basic properties of the model (1). The total population size N satisfies the equation

and hence

Therefore, the biologically feasible region for the system (1)

is bounded and positively invariant. Thus, all the solutions inside the region Ω will be considered, where uniqueness of the solutions, and the usual existence and continuation results are satisfied.

The disease-free equilibrium (DFE) for the system (1) is \(E^{0}=(S^{0},0,0,R^{0})\), where

which, respectively, shows the level of susceptible, recovered, and not infected population of total individuals. The disease-free equilibrium point is

The basic reproduction number is an important threshold quantity that mathematically analyzes the disease spread and control. This formula is very helpful to find the information as regards an infectious disease spreading and being under control in a community. For the disease-free states the threshold quantity \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}<1\) holds, then this equilibrium will be stable and their will be no disease spread in the community and the disease can be handled through some preventive vaccination or prevention. In the case of failure, the disease becomes an epidemic and permanently exists in the population when \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\). To find the basic reproduction number for our model, we follow [27].

Let \(x = (E, I)\), then it follows from system (1) that

The inverse of V is

Thus, for the system (1), the next generation matrix is

The spectral radius \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}\) of the matrix \(FV^{-1}\) is

and it is the required basic reproduction number for the system (1).

2.2 Endemic equilibria

The endemic equilibrium for the system (1) at the point \(E^{1}=(S^{*},E^{*},I^{*},R^{*})\) is

Making use of \(S^{*}\), \(E^{*}\), and \(R^{*}\) in the fourth equation of system (3), we obtain the following equation for I:

Since \(\frac{(\mu+\mu_{1})(\mu+\mu_{0}+\mu_{2})}{\mu_{1}}-\frac{\mu_{3} \mu_{2}}{(\mu+\mu_{3})}>0\) and \(\psi'\ge0\), and for large positive values of I, Φ is a decreasing function. Moreover, \(\Phi(I)<\frac{\Lambda((1-q)\mu+\mu_{3})}{(\mu+\mu_{3})}- (\frac{(\mu +\mu_{1})(\mu+\mu_{0}+\mu_{2})}{\mu_{1}}-\frac{\mu_{3} \mu_{2}}{(\mu+\mu_{3})} )I\), then

Next, to find the sign of the derivative,

since \((\frac{(\mu+\mu_{1})(\mu+\mu_{0}+\mu_{2})}{\mu_{1}}-\frac{\mu_{3} \mu_{2}}{(\mu+\mu_{3})} )>0\) and clearly \(\psi(\dot{I})\geq0\).

Suppose \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}=\frac{\mu_{1}\beta \Lambda((1-q)\mu+\mu_{3})}{\mu(\mu+\mu_{1})(\mu+\mu_{3})(\mu+\mu_{0}+\mu_{2})}\). Since \(\psi(0)=1\), it follows that

A unique positive zero of Φ exists if and only if \(\Phi(0)>0\), i.e., \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\). It can be stated as follows.

Proposition

Suppose the conditions imposed on the function \(\psi(I)\) are satisfied. Then there exists a disease-free state for system (1), which is \(E^{0}=(\frac{\Lambda((1-q)\mu+\mu_{3})}{\mu(\mu+\mu_{3})},0,0, \frac{q\Lambda}{\mu+\mu_{3}})\), which exists for all parameter values. For \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\), the endemic equilibrium \(E^{1}\) admits the unique positive equilibrium for the system (1).

3 Local stability

In this section, we investigate the local stability analysis of the model (1). First, we find the local stability of the disease-free and then the endemic equilibrium as will be discussed.

Theorem 3.1

The disease-free equilibrium point \(E^{0}\) of the system (1) we have the following.

-

(i)

It is stable locally asymptotically if \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}\leq1\).

-

(ii)

An unstable equilibrium exists if \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\).

Proof

(i) At the disease-free equilibrium point \(E^{0}\), the Jacobian matrix of (1) is

The characteristic equation of the \(J_{0}\) is given by

One of the negative roots of the above characteristics equation is −μ, while the remaining roots can be obtained in the following way:

where

The Routh-Hurwitz criterionFootnote 1 for the cubic equation is as follows:

We obtain

Thus, the system (1) around the disease-free equilibrium point \(E^{0}\) is locally asymptotically stable if \({\mathcal {R}}_{0}\leq1\).

(ii) When \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\), then \(Q_{2}<0\) and \(Q_{3}<0\), which is a failure of the Routh-Hurwitz criterion. So, in this case the equilibrium is unstable. □

In the next theorem, we will prove that the system (1) around the endemic equilibrium point \(E^{1}\) is stable locally asymptotically, when the basic reproduction number \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}> 1\).

Theorem 3.2

If \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}> 1\), then the endemic equilibrium point \(E^{1}\) of the system (1) is locally asymptotically stable, otherwise it is unstable.

Proof

The Jacobian matrix of the system (1) at \(E^{1}\) is given by

The characteristic equation of \(J^{[*]}\) is given by

One of the eigenvalues of the \(J^{[*]}\) is negative, −μ, while the remaining eigenvalues can be obtained in the following way:

where

Now

After a little algebraic calculation, we get

Thus, the Routh-Hurwitz criterion is satisfied. So, the endemic equilibrium point \(E^{1}\) of the system (1) is locally asymptotically stable. □

In the next section, we will find the global stability of the disease-free and endemic equilibrium. Before we do this, first, we reduce the system (1), by using \(R(t)=\frac{\Lambda}{\mu}-S(t)-E(t)-I(t)\) to eliminate \(R(t)\) from the first equation of system (1), which leads to the following reduced three dimensional model:

subject to the initial conditions:

The disease-free equilibrium point for system (4) is denoted by \(E_{0}\) and the endemic equilibrium point is \(E_{1}\).

4 Global stability

The aim of this section is to investigate the global stability of disease-free and endemic state. To find the global stability of the disease-free state we use the method presented in [28]. According to [28], the conditions (\({\mathcal{H}}_{1}\)) and (\({\mathcal{H}}_{2}\)) are necessary, then the stability of a disease-free state exists. Following [28], we rewrite the system (1) in the following form:

where \(\overline{X}=S\) represents the number of uninfected individuals, while \(Z=(E,I)\) represents the infected number of individuals, with \(\overline{X} \in\mathbb{R}\) and \(Z \in \mathbb{R}^{2}\), respectively. We denote the disease-free equilibrium by \(\overline{Q}^{0}=(\overline{X}^{0}, 0)\). The conditions (\({\mathcal{H}}_{1}\)) and (\({\mathcal{H}}_{2}\)) are necessary for the existence of the global stability of the disease-free state:

- (\({\mathcal{H}}_{1}\)):

-

for \(\frac{d\overline{X}}{dt}=F(\overline{X},0)\), \({\overline{X}^{0}}\) is globally asymptotically stable (g.a.s.),

- (\({\mathcal{H}}_{2}\)):

-

\(G(X,Z)=BZ-\overline{G}(\overline {X},Z)\), where \(\overline{G}(\overline{X},Z)\geq0\), for \((\overline{X}, Z)\in \Omega\),

where \(B=D_{z} G(\overline{X}^{0},0)\) is an M-matrix (the off-diagonal elements of B are non-negative) and Ω is the region where the model makes biological sense. Then the following lemma holds.

Lemma 4.1

If \({\mathcal{R}}_{0} < 1\), then the fixed point \(\overline {Q}^{0}=(\overline{X}^{0},0)\) of reduced system (4) is said to be globally asymptotically stable if the conditions (\({\mathcal{H}}_{1}\)) and (\({\mathcal{H}}_{2}\)) are satisfied.

Now we prove the following theorem.

Theorem 4.1

Suppose \({\mathcal{R}}_{0} < 1\), then the equilibrium point \(E^{0}\) is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof

Let \(\overline{X}=(S)\) represent the number of uninfected classes and \(Z=(E, I)\) represent the number of infected classes including the exposed and infected, and \(\overline{Q}^{0}=(\overline{X}^{0},0)\), where

Then

We have \(S=S^{0}\), \(F(\overline{X}, 0)=0\), and

as \(t\to\infty\), \(\overline{X}\to\overline{X}^{0}\). So, \(\overline{X}=\overline{X}^{0}=(S^{0})\) is globally asymptotically stable. Now

where

In the reduced system (4), the total population is bounded by \(S^{0}=\frac{\Lambda((1-q)\mu+\mu_{3})}{\mu(\mu+\mu_{3})}\), i.e., \(S,E,I \le S^{0}\), and \(\beta S^{0} I \geq\frac{\beta SI}{\psi(I)}\). So \(\overline{G}(\overline{X}, Z)\geq0\), and obviously B represents an M-matrix. Thus, the conditions (\({\mathcal{H}}_{1}\)) and (\({\mathcal {H}}_{2}\)) are satisfied, so by Lemma 4.1, the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}\) of the system (4) is globally asymptotically stable, provided that \({\mathcal{R}}_{0} < 1\). □

4.1 Global stability of endemic equilibrium

In this subsection, we use the method of Li and Muldowney [29], the geometric approach method, for the global stability of an endemic equilibrium. We find the sufficient conditions for which the endemic equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable. We first briefly explain the geometric approach method. Consider

where \(f :D \to R^{n}\), \(D \subset R^{n}\) is an open set and simply connected and \(f \in C^{1}(D)\). Representing by \(x(t, x_{0})\) the solution of (5), i.e., \(f(x^{*})=0\), let us assume the hypotheses presented now are satisfied:

- (\({\mathcal{H}}_{3}\)):

-

A compact absorbing set exists, i.e., \(K \subset D\).

- (\({\mathcal{H}}_{4}\)):

-

A unique equilibrium for (5) is \(X^{*}\) in D.

If all the trajectories in D converge to \(x^{*}\) and are locally stable, then the point \(x^{*}\) is known to be stable globally in D. For \(m\geq2\), by a Bendixson criterion we mean a condition satisfied by f which precludes the existence of non-constant periodic solutions of (5). The classical Bendixson condition, \(\operatorname{div}f(x)<0\), for \(m=2\), is robust under \(C^{1}\), in view of the robustness properties discussed in [29] and [30].

A point \(x_{0} \in D\) is wandering for (5) if there exists a neighborhood U of \(x_{0}\) and \(T>0\) such that \(U\cap x(t, U)\) is null \(\forall t>T\). We present the global-stability principle of [29] for an autonomous systems as follows.

Lemma 4.2

Let the two conditions (\({\mathcal{H}}_{3}\)) and (\({\mathcal{H}}_{4}\)) hold, assuming that (5) satisfies the Bendixson criterion, i.e., robustness under \(C^{1}\), for the local perturbations of \(f(x)\) at all non-equilibrium non-wandering points for (5). Then \(x^{*}\) is globally stable in D, provided it is stable.

The following Bendixson criterion, which is given in [29], proves the robustness which is required by Lemma 4.2. Let \(P(x)\) represent

a matrix valued function, i.e., \(C^{1}\) on D, also \(P^{-1}\) exists and is continuous for \(x \in K\), the compact absorbing set. We define the quantity \(\bar{q}\) as

where

the matrix \(P_{f}\) is

and the matrix \(J^{[2]}\) represents the second additive compound matrix of the Jacobian matrix J, i.e., \(J(x)=D f(x)\). Let \(\Im(B)\) represent the Lozinskii measure of B with respect to the vector norm \(|\cdot|\) in \(R^{M}\),

defined by

In [29] it is proved that, if D is connected simply, then the condition \(\bar{q} < 0\) deletes the presence of any orbit that gives rise to a simple closed rectifiable curve which is invariant for (5), like for the periodic orbits and heteroclinic cycles. The global-stability result which is proved in Li and Muldowney [29] is stated in the following.

Lemma 4.3

Let the simple connectivity of D together with the conditions (\({\mathcal{H}}_{3}\)) and (\({\mathcal{H}}_{4}\)) hold. Then \(x^{*}\), the equilibrium point of (5), is stable globally in D if \(\bar{q} < 0\).

Using the approach of [29], we find the global stability of an endemic equilibrium. In the case that \(E^{0}\) is unstable, the uniform persistence exists [31], i.e., there exists a constant \(a > 0\), such that any solution \((S(t),E(t),I(t))\) with \((S(0), E(0), I(0))\) in the orbit of the system (4) satisfies

Consider the following assumption:

Theorem 4.2

If \({\mathcal{R}}_{0} > 1\), then the endemic equilibrium \(E_{1}\) of the system (4) is globally stable in Ω.

Proof

To prove that the reduced model (4) is globally asymptotically stable, we obtain the second additive compound matrix \(J^{[2]}\) of the system (4):

Let us choose the function

Then

Also we have

Therefore

Let

where

Suppose the norm in \(R^{3}\) to be

where \((v_{1}, v_{2}, v_{3})\) represents the vector in \(R^{3}\) and we denoted by ℑ the Lozinskii measure with respect to this norm, following [32]. We have

where \(|B_{21}|\) and \(|B_{12}|\) are the matrix norms with respect to the ℑ norm, then

where

∴

using the second equation of system (4),

So, we can write

Again,

where

and \(|B_{21}|=\mu_{1}\frac{E}{I}\). Then

using the third equation of system (4), \(\frac{\mu_{1}E}{I}=\frac{\dot{I}}{I}+\mu+\mu_{0}+\mu_{2}\),

This holds along each solution \((S(t), E(t), I(t))\) of the system with \((S(0), E(0), I(0))\in K\), where K is the compact absorbing set. We have

\(d=(\mu+c)\), which implies that

Thus, by the result of [29] it implies that \(E_{1}\) is globally asymptotically stable. □

5 Discussion

The aim of this work is to study and analyze the dynamic behavior of an epidemic model SEIRS with a non-linear incidence and a waning preventive vaccination. In some previous work it has appeared [4, 7, 15, 20, 33]. In our work, we considered a mathematical model of the SEIRS type and obtained its basic reproduction number, to determine its dynamical behavior of the model. For the disease-free case the basic reproduction number \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}<1\), holds, and we found that the model is stable globally asymptotically. In epidemiology if \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}\leq1\) the disease dies out from the community and the population can be prevented by vaccination or prevention. If \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}>1\), the endemic equilibrium is stable locally as well as globally. In such a case the disease becomes endemic and permanently exists in the community. For \(q=0\), the basic reproduction number for the vaccination-free model is

Thus, we can write \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}\) as

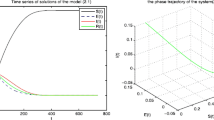

If \({\mathcal{R}}_{1}\leq1\), then clearly the disease vanishes or dies out from the population. But if \({\mathcal{R}}_{1}>1\) (Figure 2 illustrates this fact), then vaccination is needed so that \({\mathcal{R}}_{0}\leq1\) or equivalently

Thereby, if \(q_{v} \le1\), \(q_{v}\) acts as the coverage ability of the optimal vaccination of the disease eradication from the community (Figures 3 and 4 illustrate this fact). In the case (\(q_{v} \ngtr1\)), it becomes epidemic and persistent, even though all the newborn are vaccinated (Figure 5 illustrates this fact). It is to be noted, when \({\mathcal{R}}_{1} > 1\), that \(q_{v}\) represents the increasing function of \(\mu_{3}\) and \(q_{v} >1\) is satisfied if and only if \(\mu_{3} > \frac{\mu}{{\mathcal{R}}_{1}-1}\). Thus, once we increase the loss as regards immunity duration which is induced by vaccination, \(\frac{1}{\mu_{3}}\), we can reduce the optimal vaccine coverage \(q_{v}\). For the control of an epidemic, the public health management are advised to make an increase in the duration as regards the loss of immunity.

The dynamical behavior of system ( 1 ), for different initials conditions and the parameters: \(\pmb{\mu_{0}=0.004}\) , \(\pmb{\mu_{1}=0.003}\) , \(\pmb{\mu_{2}=0.009}\) , \(\pmb{\mu_{3}=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=0.09}\) , \(\pmb{\Lambda =8}\) , \(\pmb{\beta=0.002}\) , \(\pmb{q=0}\) , here \(\pmb{\psi(I)=\frac{1}{1+I^{2}}}\) , \(\pmb{{\mathcal {R}}_{1}=1.5851}\) .

The dynamical behavior of system ( 1 ), for different initials conditions and the parameters: \(\pmb{\mu_{0}=0.07}\) , \(\pmb{\mu_{1}=0.003}\) , \(\pmb{\mu_{2}=0.009}\) , \(\pmb{\mu_{3}=0.001}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=0.1}\) , \(\pmb{\Lambda =10}\) , \(\pmb{\beta=0.002}\) , \(\pmb{q=1}\) , here \(\pmb{\psi(I)=\frac{1}{1+I^{2}}}\) , \(\pmb{{\mathcal {R}}_{1}=1.0251}\) .

Notes

Routh-Hurwitz criteria for the system of \(3\times3\) matrix: \(Q_{1}>0\), \(Q_{2}>0\), \(Q_{3}>0\), and \(Q_{1} Q_{2}-Q_{3}>0\).

References

Korobeinikov, A, Maini, PK, Walker, WJ: Estimation of effective vaccination rate: pertussis in New Zealand as a case study. J. Theor. Biol. 224, 269-275 (2003)

Hethcote, HW: The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Rev. 42, 599-653 (2000)

Kermack, WO, McKendrick, AG: A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. A 115, 700-721 (1927)

Mena-Lorca, J, Hethcote, HW: Dynamic models of infectious diseases as regulator of population sizes. J. Math. Biol. 30, 693-716 (1992)

Guo, H, Li, MY, Shuai, Z: Global stability of the endemic equilibrium of multigroup SIR epidemic models. Can. Appl. Math. Q. 14, 259-284 (2006)

Cheng, Y, Pan, Q, He, M: Disease control of delay SEIR model with nonlinear incidence rate and vertical transmission. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2013, Article ID 830237 (2013) doi:10.1155/2013/830237

Capasso, V, Serio, G: A generalization of the Kermack-McKendrick deterministic epidemic model. Math. Biosci. 42, 41-61 (1978)

Muroya, Y, Li, H, Kuniya, T: Complete global analysis of an SIRS epidemic model with graded cure and incomplete recovery rates. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 410, 719-732 (2014)

Denphedtnong, A, Chinviriyasit, S, Chinviriyasit, W: On the dynamics of SEIRS epidemic model with transport-related infection. Math. Biosci. 245, 188-205 (2013)

Zhang, L, Li, Y, Ren, Q, Huo, Z: Global dynamics of an SEIRS epidemic model with constant immigration and immunity WSEAS Trans. Math. 12, 630-640 (2013)

Zhang, Z, Yang, H: Stability and Hopf bifurcation in a delayed SEIRS worm model in computer network. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, Article ID 319174 (2013). doi:10.1155/2013/319174

Liu, WM, Levin, SA, Iwasa, Y: Influence of non-linear incidence rates upon the behaviour of SIRS epidemiological models. J. Math. Biol. 23, 187-204 (1986)

Ruan, S, Wang, W: Dynamical behavior of an epidemic model with a nonlinear incidence rate. J. Differ. Equ. 188, 135-163 (2003)

Korobeinikov, A, Maini, PK: A Lyapunov function and global properties for SIR and SEIR epidemiological models with nonlinear incidence. Math. Biosci. Eng. 1, 57-60 (2004)

Xiao, D, Ruan, S: Global analysis of an epidemic model with nonmonotone incidence rate. Math. Biosci. 208, 419-429 (2007)

Lyapunov, AM: The General Problem of the Stability of Motion. Taylor & Francis, London (1992)

Beretta, E, Capasso, V: On the general structure of epidemic systems. Global asymptotic stability. Comput. Math. Appl. 12A, 677-694 (1986)

Korobeinikov, A, Wake, GC: Lyapunov functions and global stability for SIR, SIRS and SIS epidemiological models. Appl. Math. Lett. 15, 955-961 (2002)

Iggidr, A, Mbang, J, Sallet, G, Tewa, JJ: Multi-compartment models. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2007, suppl. 2, 506-519 (2007)

Lahrouz, A, Omari, L, Kiouach, D: Global analysis of a deterministic and stochastic nonlinear SIRS epidemic model. Nonlinear Anal., Model. Control 16, 59-76 (2011)

Lahrouz, A, Omari, L, Kiouach, D, Belmaati, A: Deterministic and stochastic stability of a mathematical model of smoking. Stat. Probab. Lett. 81, 1276-1284 (2011)

Lahrouz, A, Omari, L, Kiouach, D, Belmaati, A: Complete global stability for an SIRS epidemic model with generalized non-linear incidence and vaccination. Appl. Math. Comput. 218, 6519-6525 (2012)

Sahu, GP, Dhar, J: Analysis of an SVEIS epidemic model with partial temporary immunity and saturation incidence rate. Appl. Math. Model. 36, 908-923 (2012)

Zhou, X, Cui, J: Analysis of stability and bifurcation for an SEIV epidemic model with vaccination and nonlinear incidence rate. Nonlinear Dyn. 63, 639-653 (2011)

Korobeinikov, A, Maini, PK: Nonlinear incidence and stability of infectious disease models. Math. Med. Biol. 22, 113-128 (2005)

Capasso, V: Mathematical Structures of Epidemic Systems, 2nd edn. Springer, Heidelberg (2008)

Van den Driessche, P, Watmough, J: Reproduction number and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 180, 29-48 (2002)

Castillo-Chavez, C, Feng, Z, Huang, W: Mathematical Approaches for Emerging and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases: An Introduction, vol. 126, pp. 261-273. Springer, Berlin (2002)

Li, MY, Muldowney, JS: A geometric approach to global-stability problems. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 27, 1070-1083 (1996)

Li, MY, Muldowney, JS: On R.A. Smith’s autonomous convergence theorem. Rocky Mt. J. Math. 25(1), 365-378 (1995)

Freedman, HI, Ruan, S, Tang, M: Uniform persistence and flows near a closed positively invariant set. J. Differ. Equ. 6(4), 615-626 (2006)

Martin, R: Logarithmic norms and projections applied to linear differential systems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 45, 432-454 (1974)

Korobeinikov, A: Lyapunov functions and global stability for SIR and SIRS epidemiological models with non-linear transmission. Bull. Math. Biol. 30, 615-626 (2006)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Education Malaysia (MOEM) and Research Management Centre UTM for the financial support through vote numbers 06H67 and 4F255 for this research. The authors would also like to thank to the anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.A., Badshah, Q., Islam, S. et al. Global dynamics of SEIRS epidemic model with non-linear generalized incidences and preventive vaccination. Adv Differ Equ 2015, 88 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0429-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0429-3