Abstract

Background

A growing body of literature indicates that, worldwide, immigrants experience health deterioration after their arrival into their adopted country, and moreover, they have lower vitamin D compared to the native-born population. We plan to review if the levels of vitamin D are comparable between different ethnic groups in different regions of the world with those of native-born populations and to identify the possible associations between vitamin D deficiency and disease status among immigrants.

Methods/design

A systematic review and meta-analysis will be conducted following the methods of the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews. A literature search was performed to identify studies on immigrants and vitamin D. The primary outcome is vitamin D levels, and the secondary outcome is any vitamin D deficiency-related disease. Study design and participant characteristics will be extracted, including ethnicity, country of birth and/or origin, and the host country. Descriptive and meta-analytic summaries of the outcomes will be derived. Distiller-SR and RevMan will be used respectively for data management and meta-analysis.

Discussion

This systematic review may partially help clarify vitamin D-related health deterioration in migrants; moreover, to develop a global guideline that specifies sub-populations, in which the evidence and vitamin D-related recommendations might differ from the overall immigrant population.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42018086729

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthy people are more likely to migrate, and those with serious medical conditions may be disqualified [1, 2]. Despite particular groups, such as refugees, who are not as healthy as other immigrants, substantial evidence indicates that the health of immigrants at the time of arrival is significantly better than the health of the native-born population of the host country [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Recent studies have shown that the physical and mental health of immigrants declines after their arrival into the adopted country [2, 4, 8,9,10,11,12], and health changes can occur within 5 to 10 years [9, 13,14,15]. Migration studies suggest that the integration process is likely a new experience for immigrants, in which changes in the environment and lifestyle are well-documented factors predisposing migrants to chronic diseases [8, 16, 17]. Moreover, migration experience and post-migration integrations are believed to explain the decline in the health status of immigrants [4, 11, 18]. However, the mechanistic reasons underlying the decline in immigrants’ health have not been explicitly identified [4, 14]. Worldwide research evidence suggests that migration is a significant risk factor for low vitamin D levels due to resettlement changes in lifestyle and sun exposure [19,20,21,22]. Vitamin D plays a crucial role in physiological functions; it regulates the absorption of calcium and phosphorus that support both skeletal (bone hemostasis) and non-skeletal health [23, 24].

The dietary sources for vitamin D are plant-based foods (e.g., mushroom) which include vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and the animal-based foods (e.g., salmon and tuna fish) which include vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) [21, 25]. In addition to the natural food-based sources, the human body obtains vitamin D from artificial sources such as supplements and fortified food. The primary source, however, is through skin exposure to the sunlight (cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D) [26], and therefore, vitamin D is commonly known as the ‘sunshine vitamin’ because the body can make it through exposure to sunlight whereas most other vitamins are food-based ingestion [27]. However, the ability of body to create and maintain sufficient levels affected by socio-demographic factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, age, and gender), geographical and environmental factors (e.g., season and the latitude), cultural and religious factors (e.g., clothing, sedentary behaviors and prolonged breastfeeding time), lifestyle and dietary factors (e.g., vegetarian diet), as well as genetic and health factors (e.g., skin pigmentation and obesity) [20, 23, 28,29,30]. A study on people from different ethnic origin who have similar practices proposes that skin pigmentation is possibly the most significant risk factor for vitamin D deficiency irrespective of the ultraviolet light exposure [31].

The concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D serum (25(OH)D) represents the combined contributions of the cutaneous synthesis and the dietary intake of vitamin D and is considered the best clinical indicator for the overall adequacy of vitamin D [23, 25, 27]. There is no international agreement regarding the reference range for serum 25(OH) D concentrations. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has developed different categories for the concentration levels of the serum 25(OH)D in blood, which include optimal (> 75 nmol/l), sufficient (> 50 nmol/l), inadequate or deficient (≤ 50 nmol\l), and deficient (< 30 nmol/l) levels [27]. According to the World Health Organization, the levels of serum 25(OH)D below 50 nmol/l were classified as insufficient and levels below 25 nmol/l were considered as deficient [32].

Vitamin D deficiency is a global pandemic health problem in all age groups that occurs in countries with both high and low levels of sunlight (degree of the latitudes) [23, 24]. Hilger et al. in a systematic review of studies from 44 countries with data from 112 articles (168,389 participants), reported a wide range of serum 25(OH)D between 4.9 and 136.2 nmol/l with age and sex variations. Mean levels of < 50 nmol/l were reported in one third of these studies [33]. The highest levels of serum 25(OH)D were among participants who live in North America while those who live in the Middle East and Africa regions have much lower levels [33].

Studies show that worldwide migrant populations, including refugees and asylum, have lower levels of vitamin D compared with the local populations [20, 30, 34]. Refugees are considered at particularly higher risk for vitamin D deficiency due to staying indoors to avoid dangers, cold weather, living in high-rise buildings that limit their outdoor activities and sun exposure, and concerns regarding skin cancer [20]. The age, ethnicity, country of origin, higher latitudes, nutritional barriers, cultural practices, and the length of time after immigration were reported in several studies as being associated with the risk of vitamin D deficiency among immigrants [20, 30, 36]. Migrants are often considered as low-SES individuals, and immigrants of low SES were found to have a higher risk of vitamin D deficiency [35], as well as to develop physical and mental illnesses [16, 30, 36].

Previous studies support the hypothesis that the inadequate or deficient level of vitamin D is associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality and a wide range of physical and mental health diseases, including osteoporosis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity, schizophrenia and depression, and the metabolic syndrome [17, 23, 33, 36,37,38,39].

Although there is disagreement about optimal levels of serum 25(OH)D, evidence suggests that levels < 30 nmol/l are associated with an increased risk of some diseases in which vitamin D deficiency has been found to play a role. Moreover, the thresholds for serum 25(OH)D may vary according to different outcomes and subgroups, and the most advantageous levels begin at 75 nmol/l [40,41,42,43].

The most relevant systematic review to this protocol published by Martin et al. 2016 has focused on dark skin immigrants including both first- and second-generation immigrants. Moreover, the included studies were selected from certain regions associated with dark skin, namely, Africa; West, South, Central, and Southeast Asia; the Middle East; the Caribbean, and Central America [20]. Whereas the current systematic review will include only the first-generation immigrants who were defined as foreign-born population and no geographical restrictions will be applied. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has systematically reviewed the vitamin D deficiency-related diseases and immigrant status.

The aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis are the following: first is to compare the levels of vitamin D between ethnic groups of immigrants in different regions with those of native-born populations. Consequently, the findings will be used to establish global maps for vitamin D status of immigrants and non-immigrants, as well as maps for the same ethnic immigrants (at high risk) in different geographical regions of the world. Second is to identify the possible associations between vitamin D deficiency and disease status among immigrants.

Methods/design

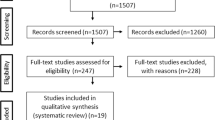

The protocol of this review has been registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018086729) [44]. The strategy involves a comprehensive systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. The procedures will follow the methods outlined in the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews [45]. This includes guidance in planning the review, searching and selecting studies, collecting data, as well as the risk of bias and prospective meta-analysis. The protocol of this systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) Statement [46]; the checklist is presented in Additional file 1.

Literature search

A systematic literature search was performed to identify studies on immigrants and vitamin D. The primary search strategy was completed in MEDLINE(R) ALL (Ovid) by a medical information specialist using a combination of subject headings and keywords. The strategy was peer-reviewed by an independent information specialist using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines [47]. The final search strategy was run on August 16, 2018, and translated to EMBASE Classic + Embase (Ovid) (available in Additional file 2), PubMed, and Web of Science Indexes (SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, ESCI) on the same day, and to Cochrane (Wiley on INSERT DATE). With regard to the grey literature, Dissertations and Theses Global (ProQuest) was searched as well as international and governmental websites, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), and the National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE). Supplemental searches will be performed using backward chaining (looking through the bibliographies of included studies for additional relevant articles).

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Two reviewers independently will follow the population, exposure, comparator, and outcomes (PECO) criteria in evaluating the included studies. The population of interest is immigrants, defined as foreign-born. The exposure is the integration process over time in the new environment after immigration, and the comparator is the non-immigrant (native-born population). The primary outcome is vitamin D levels, and the secondary outcome is any vitamin D deficiency-related disease (e.g., cardiovascular, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, depression, chronic pain, and respiratory infections).

All study designs will be eligible except the following publication types: case reports, case series, systematic or narrative reviews, editorials, and commentaries. Studies will be excluded if they do not define or include migrant status, including populations at higher risk for vitamin D deficiency such as chronic illness, and if the concentration levels of vitamin D are not reported. The publication with the largest sample size will be included if the same population is presented in more than one publication. No studies will be excluded from the search based on the language and the study date.

All studies will be independently screened and evaluated for eligibility by two reviewers, and any disagreement will be discussed and resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis

The data will be extracted by two independent reviewers. If necessary, discrepancies will be resolved through discussion [48]. Standardized and piloted forms for data extraction will be used to extract the characteristics of the studies and participants, as well as the specific details from each study (e.g., ethnicity, country of birth and/or origin, and the host country). Data for all immigrants and a priori defined subgroups will be extracted. Based on the availability, the mean and/or the median of the concentration levels of vitamin D will be summarized in a tabular format, pooled via meta-analysis, and used to compare immigrants to non-immigrants. Descriptive statistics will be implemented for the baseline features of the included studies. The vitamin D status will be identified based on the IOM categories (optimal, adequate, insufficient, or deficient) [27]. When the concentration level of vitamin D is given as nanograms per milliliter, it will be multiplied by 2.496 to attain the nanomoles per liter [49]. Participant and study characteristics of the included studies will be used to assess the clinical and methodological heterogeneity, respectively. The heterogeneity between the included studies will be completed through a visual assessment of forest plots and the calculation of the I2 statistic, which provides a numerical summary of heterogeneity. The following categories of I2 statistic will be considered: < 25%, 25 to 50%, and 50 to 75%. For I2 > 50, heterogeneity will be explored using subgroup and meta-regression. If the reason for heterogeneity is identified, it will be reported accordingly. If heterogeneity is not resolved, the results will be pooled for I2 between 50 and 75%, and a caveat regarding the heterogeneity will be provided. For I2 > 75%, the results will not be pooled. Outcome data will be pooled using a random-effects model. Distiller SR and RevMan will be used to complete data extraction and meta-analyses, respectively.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

Depending on the availability and the quality of data (risk of bias), subgroup analysis will be conducted based on age, sex, ethnicity, country of birth and/or origin, geographical location and the latitude of the host country for immigrants, season, the immigration class (family, economic, and refugee classes), and the time since immigration.

Risk of bias and quality evaluation

The quality of the included studies will be assessed using the relevant tools depending on the study design. These tools may include Joanna Briggs, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network-Publication no.50 (SIGN50), Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Exposure (ROBINS-E), as well as Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool (ROB v. 2.0) [45, 50,51,52]. Two independent reviewers will evaluate the quality, and any disagreements between reviewers will be discussed and resolved by consensus.

Discussion

The baseline risk for vitamin D deficiency is higher among migrants especially those who have darker skin, such as Middle Eastern and African populations, and those who migrate from equatorial region to northern latitude [20, 33, 53]. Cultural and lifestyle practices that minimize sun exposure also increase the risk in these subgroups [20]. However, the developed recommendations for vitamin D supplementation provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) still inadequately address the growing epidemic of vitamin D insufficiency in immigrants and refugees [49]. For instance, the DRIs for vitamin D and calcium sets the recommended of daily intake assuming minimal sun exposure for all populations. Moreover, no additional recommendations are given for sub-populations such as immigrants living in high northern latitudes, those with darker skin pigmentation, or those who wear heavy clothing that inhibits sun exposure [54, 55]. In addition, most of the worldwide guidelines on vitamin D and/or immigrants’ health does not entirely address these subpopulations in their recommendations [56,57,58,59,60,61].

Nonetheless, recent reviews recommended future studies to assess relevant data on vitamin D and determinants, including lifestyle factors with a subgroup comparison of the population within the same country [33], as well as further research specific to migrant populations to establish links between immigrant status and disease status [17]. Therefore, this systematic review may partially help to clarify vitamin D-related health deterioration in migrants and moreover, to develop a global guideline that specifies sub-populations, in which the evidence and recommendation might differ from the overall immigrant population.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D:

-

25-Hydroxyvitamin D serum

- A&HCI:

-

Arts and Humanities Citation Index (1975–present)

- CIHI:

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information

- CPCI-S:

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science (1990–present)

- CPCI-SSH:

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science and Humanities (1990–present)

- DRIs:

-

Dietary Reference Intakes

- ESCI:

-

Emerging Sources Citation Index (2005–present)

- IOM:

-

Institute of Medicine

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health Care Excellence

- PECO:

-

Population, Exposure, Comparator, and Outcomes

- PRESS:

-

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol

- ROB:

-

Risk of bias tool

- ROBINS-E:

-

Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Exposure

- SCI-EXPANDED:

-

Science Citation Index Expanded (1900–present)

- SIGN50:

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network-Publication no. 50

- SSCI:

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (1900–present)

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Laroche M. Health status and health services utilization of Canada’s immigrant and non-immigrant populations. Can Public Policy. 2000;XXCI(1):51–73.

Solé-Auró A, Crimmins EM. Health of immigrants in European countries. Int Migr Rev. 2008;42(4). [cited 2018 Jul 31] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2967040/pdf/nihms220945.pdf

Chen J, Wilkins R, Ng E. Health expectancy by immigrant status, 1986 and 1991. Heal Rep. 1996;8(3):29–38.

Health Canada. Canadian Research on Immigration and Health. Health-Canada 1999;This publi. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.696347/publication.html

Pe’rez CE. Health status and health behaviour among immigrants [Canadian Community Health Survey - 2002 Annual Report] - ProQuest. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 112, Catalogue 82-003-SIE; 2002. p. 89–100. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-003-s/2002001/pdf/82-003-s2002005-eng.pdf?st=ERfZZ9Gx

Gee E, Kobayshi K, Prus S. Examining the “healthy immigrant effect”; in later life: findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey - ProQuest. 2003. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15660311

Dunn J, Dyck I. Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: results from the national population health survey; 1998.

Hemminki K. Immigrant health, our health. Eur J Public Health. 2014 [cited 2018 Jul 31];24(suppl 1):92–5. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/eurpub/cku108

Newbold B. Self-rated health within the Canadian immigrant population: risk and the healthy immigrant effect. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1359–70.

Kennedy S, Mcdonald JT, Biddle N. The healthy immigrant effect and immigrant selection: evidence from four countries. 2006 [cited 2016 Nov 26]; Available from: https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/sedap/papers06.htm

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 [cited 2016 Nov 26];1186(1):69–101. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x

Hansson E, Tuck A, Lurie S, McKenzie K. Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups Issues and options for service improvement [Internet]. for the Task Group of the Services Systems Advisory Committee, Mental Health Commission of Canada. 2010 [cited 2016 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/Diversity_Issues_Options_Report_ENG_0_1.pdf

Newbold B. Health status and health care of immigrants in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. J Heal Serv Res Policy Nurs Allied Heal Database pg. 2005;10:2.

Newbold B. The short-term health of Canada’s new immigrant arrivals: evidence from LSIC. Ethn Health. 2009 [cited 2016 Nov 28];14(3):315–36. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13557850802609956

Zhao J, Xue L, Gilkinson T. Health status and social capital of recent immigrants in Canada. Policy Stud. 2010 [cited 2016 Nov 26];(March). Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/cic/Ci4-139-2010-eng.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. Immigrant mental health. 2010 [cited 2017 Apr 10]; Available from: http://www.metropolis.net/pdfs/immigrant_mental_health_10aug10.pdf

Renzaho AM, Halliday BHSci JA, Nowson C. Vitamin D, obesity, and obesity-related chronic disease among ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Nutrition. 2011 [cited 2018 Jan 22];27:868–79. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0899900711000128?via%3Dihub

Beiser Morton. The international refugee crisis : British and Canadian responses - CLIO. After the door has been opened: the mental health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. 1993. Available from: https://clio.columbia.edu/catalog/1176318

Granlund L, Ramnemark A, Andersson C, Lindkvist M, Fhärm E, Norberg M. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and its association with nutrition, travelling and clothing habits in an immigrant population in Northern Sweden. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 22];70(10):373–9. Available from: http://www.nature.com.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/articles/ejcn2015176.pdf

Martin CA, Gowda U, Renzaho AMN. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among dark-skinned populations according to their stage of migration and region of birth: A meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2016 [cited 2018 Mar 19];32:21–32. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26643747

M.H. Edwards, Z.A. Cole, N.C. Harvey CC. The global epidemiology of vitamin D status. J Aging Rese Clin Pract. 2014 [cited 2018 Feb 9]. Available from: http://www.jarcp.com/703-the-global-epidemiology-of-vitamin-d-status.html

Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: a forgotten hormone important for health INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE. Public Health Rev. 2010 [cited 2018 Mar 29];32(1):267–83. Available from: https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1007/BF03391602

Simon Spedding XZ, editor. Vitamin D and human health | MDPI Books. Edition 2015. Shu-Kun Lin; 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/books/pdfview/book/120

Wacker M, Holick MF. Vitamin D—effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients. 2013 [cited 2018 Mar 22];5:111–48. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3571641/

Pham TT (Thesis for M. Vitamin D status of immigrant and ethnic minority children ages 2 to 5 y in Montréal. 2012 [cited 2018 Jan 7]; Available from: http://digitool.library.mcgill.ca/webclient/StreamGate?folder_id=0&dvs=1564852305581~524

Alshahrani AA, Alicia Garcia SC (Thesis for M degree). Vitamin D deficiency and possible risk factors among middle eastern university students in London, Ontario, Canada. 2014 [cited 2018 Jan 7]; Available from: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd

Statistics Canada. Vitamin D blood levels of Canadians based on CHMS, cycle 2. 2015 [cited 2018 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11727-eng.htm

Palacios C, Gonzalez L. Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014 [cited 2018 Mar 28];144:138–45. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239505

Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, Burckhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B, Eisman JA, et al. Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int. 2009 [cited 2018 Mar 11];20(11):1807–20. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00198-009-0954-6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for evaluation of the nutritional status and growth in refugee children during the domestic medical screening examination division of global migration and quarantine. 2013 [cited 2018 May 6]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/pdf/Nutrition-and-Growth-Guidelines.pdf

Knoss R, Halsey LG, Reeves S. Ethnic Dress, vitamin D intake, and calcaneal bone health in young women in the United Kingdom. J Clin Densitom. 2012 [cited 2018 Aug 9];15(2):250–4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1094695011001788?via%3Dihub

Rosen CJ. Clinical practice vitamin D insufficiency. Vol. 364, N Engl J Med. 2011 [cited 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21247315

Hilger J, Friedel A, Herr R, Rausch T, Roos F, Wahl DA, et al. A systematic review of vitamin D status in populations worldwide. Br J Nutr. 2014 [cited 2018 Mar 11];111:23–45. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/69657BC57AF7A214271655C5463F5293/S0007114513001840a.pdf/systematic_review_of_vitamin_d_status_in_populations_worldwide.pdf

Spiro A, Buttriss JL. Vitamin D: An overview of vitamin D status and intake in Europe. Nutr Bull. 2014 [cited 2018 Mar 28];39(4):322–50. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4288313/pdf/nbu0039-0322.pdf

Aucoin M, Dtmh C, Weaver R, Thomas R, Mrcgp C, Jones L, et al. Vitamin D status of refugees arriving in Canada Findings from the Calgary Refugee Health Program. 2013 [cited 2018 Jan 7];59. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3625101/pdf/059e188.pdf

Gaksch M, Jorde R, Grimnes G, Joakimsen R, Schirmer H, Wilsgaard T, et al. Vitamin D and mortality: Individual participant data meta-analysis of standardized 25-hydroxyvitamin D in 26916 individuals from a European consortium. Zmijewski M, editor. PLoS One. 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 28];12(2):e0170791. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170791

Dong J-Y, Zhang W, Chen J, Zhang Z-L, Han S-F, Qin L-Q. Vitamin D Intake and Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients. 2013 [cited 2018 Apr 1];5(9):3551–62. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/5/9/3551

Chu F, Ohinmaa A, Klarenbach S, Wong Z-W, Veugelers P. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and Indicators of Mental Health: An Analysis of the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Nutrients [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 10];9(10):1116. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/9/10/1116

Huotari A, Herzig K-H. Vitamin D and living in northern latitudes—an endemic risk are for vitamin D defieciency. Int J Circumpolar Heal J Circumpolar Heal. 2008 [cited 2018 Feb 9];67(3). Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8daa/fce677c71dc430264f6acc253556dcd26c60.pdf

Heaney RP. Vitamin D in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 [cited 2019 Jun 21];3(5):1535–41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18525006

Robyn Lucas & Rachel Neale. What is the optimal level of vitamin D? Separating the evidence from the rhetoric clinical. 2014 [cited 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24600673

Sohl E, De Jongh RT, Heymans MW, Van Schoor NM, Lips P. Thresholds for serum 25(OH)D concentrations with respect to different outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 [cited 2019 Jun 21];100:2480–8. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article-abstract/100/6/2480/2829682

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes 1-3. Vol. 84, Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 [cited 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article-abstract/84/1/18/4633029

Said Abdelrazeq, George A. Wells, Jesse Elliot SA. Worldwide comparison of vitamin D status in immigrants and local populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. PROSPERO. National Institute of Health Research; 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018086729

Higgins JPT GS (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011; Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. Implementing PRISMA-P: recommendations for prospective authors. Syst Rev. 2016 [cited 2018 Sep 8];5(1):15. Available from: http://www.systematicreviewsjournal.com/content/5/1/15

Mcgowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 4];75:40–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27005575

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015 [cited 2018 Apr 9];4(1):1. Available from: http://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009 [cited 2018 Apr 4];169(6):626–632. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3447083/pdf/nihms-406918.pdf

SIGN 50: a guideline developer’s handbook. [cited 2018 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-50.html

University of Bristol. ROBINS-E|Bristol Medical School: Population Health Sciences | University of Bristol. [cited 2018 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/centres/cresyda/barr/riskofbias/robins-e/

Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. [cited 2018 Oct 13]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article-abstract/36/3/666/653571

Spedding S, Simon. Vitamin D and Human Health. 2015 [cited 2018 Mar 8]; Available from: https://www.mendeley.com/research-papers/vitamin-d-human-health/?utm_source=desktop&utm_medium=1.17.13&utm_campaign=open_catalog&userDocumentId=%7B25046fc3-571c-3be3-8c74-0692c572f659%7D

Government of Canada. Vitamin D and Calcium: Updated Dietary Reference Intakes - Canada.ca. Government of Canada website. 2012 [cited 2018 May 6]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/vitamins-minerals/vitamin-calcium-updated-dietary-reference-intakes-nutrition.html#a5

Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D health effects of vitamin D and calcium intake. 2011 [cited 2018 Jul 19]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56070/

Pottie MClSc K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels MHSc H, Rashid M, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. E824 C. 2011 [cited 2018 Feb 25];(12). Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/183/12/E824.full.pdf

Government of Ontario M of H and L-TC. Clinical utility of vitamin D testing an evidence-based analysis medical advisory secretariat ministry of health and long-term care how to obtain issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series Conflict of Interest Statement. Ontario Heal Technol Assess Ser Ont Heal Technol Assess Ser. [cited YYYY MM DD [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2018 May 9];10(102):1–95. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23074397

Ministry of Health- British Columbia. B.C. Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Vitamin D Testing Protocol. 2010 [cited 2018 May 9]; Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/bc-guidelines/vitamind_summary.pdf

Alberta Medical Association. Toward optimized practice (TOP) working group for vitamin D. Guideline for vitamin D testing and supplementation in adults. Edmonton, AB: Toward Optimized Practice. 2012 [cited 2018 May 9]; Available from: http://www.topalbertadoctors.org/download/606/Guideline+for+Vitamin+D+Use+in+Adults+2012+October+31.pdf

The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Vitamin D deficiency. [cited 2018 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Vitamin_D_deficiency/

National Institute for Health Research Centre. Vitamin D: supplement use in specific vitamin D: supplement use in specific population groups population groups Public health guideline. 2014 [cited 2018 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph56/resources/vitamin-d-supplement-use-in-specific-population-groups-pdf-1996421765317

Acknowledgements

We thank Becky Skidmore, MLS, Ottawa, ON, for the peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy and subsequent translations to the other databases.

Funding

No funding

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS, MD, CI, PM, HA, and GW conceived the study. LN designed and executed the search strategy. YS and JE will screen, select the studies for inclusion, and perform the data extraction. YS drafted the protocol, which was revised by all authors. All authors have approved the version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Revised PRISMA-P checklist. (DOCX 39 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search strategy. (DOCX 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yousef, S., Elliott, J., Manuel, D. et al. Study protocol: Worldwide comparison of vitamin D status of immigrants from different ethnic origins and native-born populations—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 8, 211 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1123-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1123-4