Abstract

Introduction

Worldwide, more immigrants experience vitamin D (vitD) deficiency than non-immigrants, which is attributed to ethnic variations, place or region of birth, skin pigmentation, clothing style, and resettlement-related changes in diet, physical activity, and sun exposure. Current recommendations in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) concerning vitD are inadequate to address vitD deficiency among immigrants. CPGs may also lack guidance for physicians on vitD supplementation for immigrants. Moreover, there are concerns about the overall quality of these CPGs.

Objectives

This systematic review will collate and critically appraise CPGs relevant to immigrants’ health and vitD. Moreover, we will evaluate whether the CPGs of vitD including recommendations for immigrants and clarify whether the CPGs of immigrants include recommendations on vitD.

Methods

A systematic search of Ovid MEDLINE® ALL, EMBASE, and Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) electronic databases, guideline repositories, and gray literature will be conducted to identify relevant CPGs. Two reviewers will independently evaluate the methodological quality of the retrieved guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research, and Evaluation-II (AGREE-II) instrument. CPGs scoring ≥60% in at least four domains, including “rigor of development,” will be considered high quality.

Conclusion

Evaluating the quality and content of relevant CPGs may support researchers in developing national and global guidelines for immigrants. Furthermore, it may support vitD testing, nutritional counseling, and supplementation for vulnerable immigrant sub-populations.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42021240562.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, immigrant populations represent diverse categories including economic migrants, family members, refugees, and asylum [1, 2]. Immigrants’ health status after immigration remains an important area of concern [3, 4]. Studies have shown that immigrants’ physical and mental health declines quickly after arrival to their host countries [1, 4,5,6], and further health changes can occur over 5–10 years [4, 7]. Recent migrants are reported to have better health compared with people of the host country, including long-term migrants who had migrated to the host country at an earlier time; this phenomenon is called the “healthy immigrant effect” [8]. It has been hypothesized that the healthy immigrant effect results from a combination of pre- and post-migration factors. Pre-migration factors include biased and rigorous selection criteria that favor immigrants that are healthier, wealthier, and better educated than the general population in the country of origin [8, 9]. In addition, a decline in immigrants’ health status after arrival may be explained by psychosocial factors and lifestyle changes [9,10,11]. The mechanisms underlying this health decline in immigrants have not been explicitly identified [4]. However, the healthy immigrant effect appears to decline over time when immigrants are exposed to their new environment [5]. Evidence also suggests that immigrants have lower vitD compared with native-born populations [12,13,14]. In a recent national large-scale Canadian data, ethnicity was found the most strongly associated factor with serum vitD status among immigrants from 153 countries and more than 13 ethnicities [14]. Moreover, vitD status varies among immigrants because of skin pigmentation, clothing, place or region of birth, and resettlement changes in diet, physical activity, and sun exposure [12, 14,15,16].

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options” [17]. The main purposes of CPGs are to improve the effectiveness and quality of care and decrease variations in healthcare practices based on scientific evidence [17, 18]. Worldwide, more CPGs covering immigrants’ health have become available in the last two decades, with the main focus areas being screening, treatment, immunization, infectious diseases, mental health, and chronic diseases [2, 19, 20]. The Canadian Immigrant and Refugee Guideline refers to the first 5 years of immigration to Canada as the time during which the healthy immigrant effect begins to decline. However, the developers of this guideline highlighted the topic of vitD deficiency among immigrants as an emerging condition that was not emphasized in their guidelines [20].

CPGs covering vitD that are currently available vary among countries and professional development organizations in terms of the scope, targeted population, and recommendations [21,22,23,24]. Notably, the current recommendations for vitD are inadequate to address the growing epidemic of vitD deficiency in immigrant populations [23, 25]. Moreover, the majority of guidelines do not include specific recommendations for different immigrant populations or certain ethnic groups [21, 23, 26, 27].

In addition, concerns have been raised about the overall quality of these CPGs [2, 28, 29]. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation-II (AGREE-II) instrument has been widely used to assess guideline quality, define the information that needs to be reported, and inform guideline development [30, 31]. The overall guideline assessment includes judgment on the quality of the guideline and whether the guideline would be recommended for use [31]. Previous studies that assessed the quality of CPGs using the AGREE-II instrument were inconsistent in how they determined high quality. For example, with the inclusion of the “rigor of development” domain, a score of high quality was reported as ≥60% in at least three of the six domains [2], four of the six domains [32], or in all six domains [33].

Research objectives

This systematic review will focus on the critical appraisal of guidelines relevant to vitD and immigrants’ health using the AGREE-II instrument. Moreover, it aims to evaluate the guideline content to clarify whether recommendations for immigrant populations were included in vitD guidelines and whether vitD recommendations were included in immigrant guidelines.

Research questions

The appraisal will be based on specific research questions and clarify whether the included CPGs comply with the quality standards of the AGREE-II instrument. The research questions are as follows: “Do immigrant CPGs include recommendations on vitD?” and “Do vitD CPGs include recommendations for immigrants, including refugees and asylum seekers?”

Methods and study design

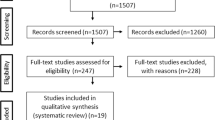

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021240562) [34]. The review procedures will follow the methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [35]. This protocol followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) Statement [36]; the checklist is presented in Additional file 1.

Search strategy

The search strategy used to identify published CPGs covering immigrants and vitD will be developed in consultation with an experienced medical information specialist. The databases searched will include Ovid MEDLINE® ALL and EMBASE. These searches will use a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “VitD,” “emigrants and immigrants,” “refugees”) and keywords (e.g., “vitD,” “asylum seeker,” “foreigner”) and incorporate a CADTH-derived guideline filter. The Ovid MEDLINE search strategy is presented in Additional file 2.

We will also search the Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database. In addition, we will search gray literature for guidelines that were internally produced by governments, organizations, and academic institutions and that publishing is a secondary activity for these organizations. For example, a search in the Guidelines International Network (GIN), Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), World Health Organization (WHO), Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and National Institution for Excellence (NICE) will be conducted. Results will be limited to relevant publications between 2010 and the date of the search. Supplemental searching will be performed on the reference lists of identified CPGs to detect other key articles.

Eligibility criteria

We will include two types of CPGs: those concerning immigrants’ health and those concerning vitD. The included guidelines will conform to the IOM definition of CPGs [17] and must have been published in the English language between 2010 and the search date. We will include CPGs that have recommendations intended for healthcare professionals on screening, diagnosis, management, or treatment related to immigrants’ health or vitD. No restrictions will be applied in regard to age, sex, or health status. In this review, we will define immigrants as those who move cross-country or are international migrants residing in a destination country, irrespective of legal status and generation. Therefore, any CPGs that include immigrants as a primary population will be evaluated using the AGREE-II tool. CPGs for vitD that emphasizes care for patients who are at risk for vitD deficiency in terms of evaluation, treatment, and prevention will also be evaluated using the AGREE-II tool.

Exclusion criteria

We will exclude non-English language guidelines or incomplete texts. We will also exclude healthcare guidelines that do not consider immigrants or vitD as the primary objective. Dietary or nutritional guidelines for vitD that are not intended for healthcare practices or that target the general population will also be excluded. Furthermore, we will exclude position and consensus papers as well as any other documents that are not equivalent to guidelines.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this review will be the quality score of the included CPGs based on the AGREE-II scoring tool. Secondary outcomes will be recommendations on vitD as part of immigrant guidelines and recommendations in vitD guidelines that target immigrants.

Selection of CPGs and data extraction

The systematic review software “Covidence” (www.covidence.org) will be used to remove duplicates and screen the titles and abstracts of identified GPGs. We will use the AGREE-II instrument (https://www.agreetrust.org) to evaluate the quality of the included guidelines. This tool comprises 23 items and evaluates six domains: “scope and purpose,” “stakeholder involvement,” “rigor of development,” “clarity of presentation,” “applicability,” and “editorial independence” [31]. An electronic standardized form will be used to record these data and individual items will be rated using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) [31]. More details are available in the AGREE-II manual [31]. The AGREE-II scoring sheet is presented in Additional file 3.

Two reviewers (SY and LH) will independently follow the inclusion and exclusion criteria to assess the citations for inclusion. Both reviewers will resolve differences in their decisions through discussion. A consultation with a third reviewer will be counted when a consensus cannot be reached.

One reviewer (SY) will extract the main characteristics of the included published guidelines, including the title, author(s) name(s), year of publication, country, and organization that produced the guideline, and key recommendations related to immigrants in vitD CPGs or vitD in immigrant CPGs. The extracted data will be checked by a second reviewer.

Following the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two reviewers (SY and LH) will independently evaluate the methodological quality of the included guidelines. Both reviewers had previous training in using the online AGREE-II, and the resulting study was published [32]. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion with a third reviewer to reach a consensus. The reviewers will evaluate the content of each CPG, and any additional supporting documents that are cited in the published guidelines.

Quality evaluation and data synthesis

The reviewers’ decisions on the overall quality of recommendations contained in the guidelines will be based on the context in which the AGREE-II is being used. The mean scores for each AGREE-II domain and the overall quality will be presented. A standardized score for each domain will be calculated using the formula: ((actual score—minimum score)/(maximum score—minimum score)) × 100% [37].

CPGs that score ≥60% in at least four of the six domains, including the “rigor of development” domain, will be considered high quality [32, 38,39,40]. The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) and 95% confidence intervals will be calculated to assess the overall agreement between the reviewers for each guideline. The ICC will be classified as poor (<0.40), moderate (0.40–0.59), good (0.60–0.74), or excellent (0.75–1.00) based on a previous study [41]. We will analyze and summarize the extracted data in a tabular and narrative format. The characteristics of the identified CPGs including author, year, and country with the title will be presented in a table and quality assessment information like the domain percentage score, the ICC, and the overall quality of each guideline in another table. We will narratively discuss if immigrants or ethnicity was mentioned in the guidelines of VitD. Similarly, we will narratively discuss if vitD D was mentioned in CPGs for immigrants.

Discussion

Current national immigrant health policies only cover fragmented snapshots of global immigrant health. In response to growing issues related to immigrants’ health, previous researchers recommended regional or global health-related protection agreements [42]. Furthermore, researchers recommended developing a global immigrant guideline that specifies sub-populations for which the evidence and recommendations may differ from the overall immigrant population [12, 43]. For example, the Endocrine Society guidelines recommend screening African Americans, Hispanic Americans [44], and all refugees for vitD deficiency [45]. In a recent Canadian national survey analysis, Yousef et al. (2021) reported vitD levels among immigrants from 153 origins and more than 13 ethnic groups. That study reported vitD deficiency attributable to ethnicity or country of birth was 6.6–62.1%, with the highest deficiency levels in the Japanese, Arab, and Southeast Asian ethnic groups, and among those born in Morocco, India, and Lebanon [14].

In this review, evaluating the quality and reviewing the content of the guidelines in terms of the recommendations for vitD and immigrants may support researchers in developing national and global immigrant guidelines. VitD-related recommendations may differ for sub-populations who are at high risk for vitD deficiency. Moreover, this review may also help and guide clinicians to support specific vitD testing, nutritional counseling, and supplementation for vulnerable immigrant sub-groups.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AGREE-II:

-

Appraisal of Guidelines, Research, and Evaluation II instrument

- CPGs:

-

Clinical practice guidelines

- VitD:

-

Vitamin D

- IOM:

-

Institute of Medicine

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol

- CADTH:

-

Canadian Agency For Drugs And Technologies In Health

- TRIP:

-

Turning Research Into Practice

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

References

Health Canada. Canadian research on immigration and health: Heal Canada; 1999. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H21-149-1999E.pdf.

Agbata EN, et al. Migrant healthcare guidelines: a systematic quality assessment. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(2):401–13.

Fernando G. De Maio and Eagan Kemp, The deterioration of health status among immigrants to Canada: EBSCOhost, Vol. 5, No. 5, September 2010, 462478, 2010. [Online]. Available: http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=31655445-ec33-4cb7-b2b5-dc5b315f7237%40sessionmgr4007&vid=1&hid=4206.

Newbold B. The short-term health of Canada’s new immigrant arrivals: evidence from LSIC. Ethn Health. 2009;14(3):315–36.

Kennedy S, Mcdonald JT, Biddle N. The healthy immigrant effect and immigrant selection: evidence from four countries; 2006.

E. Hansson, A. Tuck, S. Lurie, and K. McKenzie, Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups Issues and options for service improvement, for the Task Group of the Services Systems Advisory Committee, Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2010. [Online]. Available: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/Key_Documents/en/2010/Issues_Options_FINAL_English 12Nov09.pdf. (Accessed: 28 Nov 2016).

Newbold B. Health status and health care of immigrants in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. J Heal Serv Res Policy Nurs Allied Heal Database pg. 2005;10(2):77-83.

Ichou M, Wallace M. The healthy immigrant effect: the role of educational selectivity in the good health of migrants. Demogr Res. 2019;40:61–94.

Chiu M, Austin PC, Manuel DG, Tu JV. Cardiovascular risk factor profiles of recent immigrants vs long-term residents of Ontario: a multi-ethnic study. CJCA. 2012;28:20–6.

Morton B. The International refugee crisis : British and Canadian responses - CLIO. After the door has been opened: the mental health of immigrants and refugees in Canada; 1993.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):69–101.

Martin CA, Gowda U, Renzaho AMN. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among dark-skinned populations according to their stage of migration and region of birth: a meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2016;32:21–32.

Spiro A, Buttriss JL. Vitamin D: an overview of vitamin D status and intake in Europe. Nutr Bull. 2014;39(4):322–50.

Yousef S, et al. Vitamin D status among first-generation immigrants from different ethnic groups and origins: an observational study using the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Nutr 2021. 2021;13(8):2702.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Guidelines for evaluation of the nutritional status and growth in refugee children during the domestic medical screening examination division of global migration and quarantine, 2013.

Granlund L, Ramnemark A, Andersson C, Lindkvist M, Fhärm E, Norberg M. Prevalence of Vitamin D deficiency and its association with nutrition, travelling and clothing habits in an immigrant population in Northern Sweden. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(3):373–9.

Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; 2011.

Kredo T, et al. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. International J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(1):122.

Swinkels H, Pottie K, Tugwell P, Rashid M, Narasiah L, C. C. for I. and R. H. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH), Development of guidelines for recently arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada: delphi consensus on selecting preventable and treatable conditions. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E928–32.

Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, Narasiah L, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E824-925.

Rusinska A, et al. Vitamin D supplementation guidelines for general population and groups at risk of vitamin D deficiency in Poland-Recommendations of the Polish society of pediatric endocrinology and diabetes and the expert panel with participation of national specialist consultants and representatives of scientific societies-2018 update. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9(246):1–21.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Vitamin D: supplement use in specific population groups, vol. 2014; 2014. p. 1–54.

Alberta Medical Association. Toward Optimized Practice (TOP) Working Group for Vitamin D. Guideline for vitamin D testing and supplementation in adults. Edmonton: Toward Optimized Practice; 2012.

Dai Z, et al. Methodological quality of public health guideline recommendations on vitamin D and calcium: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e031840.

Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):626–32.

M. of H. and L.-T. C. Government of Ontario, Clinical utility of vitamin D testing an evidence-based analysis medical advisory secretariat ministry of health and long-term care how to obtain issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series Conflict of Interest Statement, Ontario Heal. Technol Assess Ser Ont Heal. 2010;10(102):1–95 Feb [cited YYYY MM DD].

Ministry of Health-British Columbia, B.C. guidelines and protocols advisory committee. Vitamin D testing protocol, 2010.

S. Pilz et al., Vitamin D testing and treatment: a narrative review of current evidence, 2019.

Hanley DA, et al. Vitamin D in adult health and disease: a review and guideline statement from osteoporosis Canada. Cmaj. 2010;182(12):1–9.

Brouwers MC, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. C C • JUL. 2010;13(10):182.

M. C. Brouwers et al., Appraisal Of Guidelines For Research & Evaluation II, 2017.

Hayawi LM, Graham ID, Tugwell P, Abdelrazeq SY. Screening for osteoporosis: a systematic assessment of the quality and content of clinical practice guidelines, using the AGREE II instrument and the IOM Standards for Trustworthy Guidelines; 2018.

Zhou X, Xu S, Ren Q, Chen J. Quality and specific concerns of clinical guidelines for integrated Chinese and Western medicine: a critical appraisal. Evid-based Complement Altern Med. 2020;2020:1-11.

S. Yousef, L. M. Hayawi, and G. A. Wells, A systematic assessment of the quality and the content of the immigrant’s health and vitamin D’s clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) using the AGREE II instrument, PROSPERO #CRD42021240562, May-2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=240562. (Accessed: 14 Jul 2021).

G. S. (editors). Higgins JPT, Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Brouwers MC. Appraisal of guidelines for research & evaluation II -agree next steps consortium membership; 2009.

Armstrong JJ, Rodrigues IB, Wasiuta T, Macdermid JC. Quality assessment of osteoporosis clinical practice guidelines for physical activity and safe movement: an AGREE II appraisal. Arch Osteoporos. 2016;1-10.

Font-Gonzalez A, et al. Fertility preservation in children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer: quality of clinical practice guidelines and variations in recommendations. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2216–23.

Ou Y, Goldberg I, Migdal C, Lee PP. A critical appraisal and comparison of the quality and recommendations of glaucoma clinical practice guidelines. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1017–23.

Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;4:284–90.

Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):1–7.

Yousef S, et al. Study protocol: worldwide comparison of vitamin D status of immigrants from different ethnic origins and native-born populations - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):1-6.

Holick MF, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–30.

Benson J, Skull S. Hiding from the sun - vitamin D deficiency in refugees. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(5):355-7. PMID: 17492073.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Visintini, MLIS (Berkman Library, University of Ottawa Heart Institute), and Becky Skidmore, MLS, Ottawa, ON, for a peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS, HL, MD, CI, PM, HA, FM, and GW conceived this study. YS designed and will execute the search strategy. YS and HL will screen, select studies for inclusion, and perform data extraction. YS drafted the protocol, which was revised by all authors. The authors have approved the version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA-P checklist-Vit D Yousef et al..

Additional file 2.

Ovid Medline CPGs.

Additional file 3.

AGREE-II Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yousef, S., Hayawi, L., Manuel, D. et al. Assessment of the quality and content of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for vitamin D and for immigrants using the AGREE-II instrument: a protocol for systematic review. Syst Rev 11, 245 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02129-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02129-6