Abstract

This study researched the winemaking performance of new biotechnology involving the cooperation of Lachancea and Schizosaccharomyces genera in the production of wine. In all fermentations where Lachancea thermotolerans was involved, higher lactic acid concentrations appeared, while all fermentations where Schizosaccharomyces pombe was involved, lower levels in malic acid concentration took place. The sensorial properties of the final wines varied accordingly. Differences in mouthfeel properties and acidity occurred in the different fermentation trials. Fermentations with the highest concentration of hydrolyzed mannose showed the highest mouthfeel properties, but the lack of acidity reduced their overall impression. Wines made from a combination of L. thermotolerans and S. pombe showed the highest overall impression and were preferred by the tasters due to the balance between mouthfeel properties and acidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several studies have proven that specific non-Saccharomyces strains are able to improve wine quality (Fleet 2008; Jolly et al. 2014; Varela 2016; Padilla et al. 2016), resulting in the use of these non-Saccharomyces yeast species in winemaking. During the past years, alternatives to conventional alcoholic fermentation and malolactic fermentation performed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Oenococcus oeni have become available to avoid specific collateral effects such as high concentrations of acetic acid or biogenic amines, which take place under specific conditions such as those that occur in warm viticulture areas (Benito et al. 2015a). Combined fermentation (co-inoculation) involving Lachancea thermotolerans (formerly known as Kluyveromyces thermotolerans) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe seems to be the appropriate for warm viticulture areas such as Spain (Benito et al. 2016a; Benito 2018).

The deacidification ability of S. pombe allows the conversion of harsh-tasting l-malic acid to ethanol (Benito et al. 2016c) which result in acidic grape juice from northern Atlantic European grape growing regions to become smoother. However, several collateral effects described for S. pombe, such as the production of high concentrations of acetic acid are common when this species is used in winemaking (Benito et al. 2014; Roca-Domènech et al. 2018) or other fermentation industries (Minnaar et al. 2017; Satora et al. 2018). Fleet (2008) proposed that through proper programs of yeast selection, specific strains could perform fermentation processes without the formation of excessive acetic acid, ethyl acetate, hydrogen sulphide and sulphur dioxide, or other off-flavors. For example, recent research reported fermentations with low acetic acid concentrations (Benito et al. 2014; Domizio et al. 2017; Du Plessis et al. 2017) that varied from 0.1 to 0.34 g/L, while other authors reported values above 1 g/L (Mylona et al. 2016; Miljic et al. 2017) depending on the strain used.

Other Schizosaccharomyces uses besides conventional malic acid deacidification have been reported during the last few years (Benito et al. 2018). Schizosaccharomyces can reduce gluconic acid concentrations (Peinado et al. 2009) and improve wine quality made from spoiled grape juice. It also improves wine color through the production of stable pigments such as vitisins (Benito et al. 2017). It can also avoid the formation of biogenic amines and ethyl carbamate concentrations to produce healthier wines from a food safety point of view (Mylona et al. 2016). Another advantage is the polysaccharide release during aging over lees or fermentation (Palomero et al. 2009; Domizio et al. 2017), which improves mouth sensory properties.

Lachancea thermotolerans is able to increase the acidity in low acidic musts from Mediterranean warm regions (Kapsopoulou et al. 2005, 2007; Gobbi et al. 2013; Balikci et al. 2016; Benito et al. 2016b; Domizio et al. 2016) through the production of lactic acid, thereby improving sensory properties. The use of Lachancea thermotolerans has recently become popular in modern enology because of the advantages such as biocontrol applications that inhibit the presence of spoilage microorganisms (Nally et al. 2018; Benito 2018). Even though there is only one commercial strain available, some researchers are performing selection processes in order to increase the number of available clones (Escribano et al. 2018).

Mannoproteins are the second most abundant family of polysaccharides after arabinogalactan-proteins that originate from grapes (Vidal et al. 2003). Mannoproteins are released into wine from yeast cell walls during fermentation and ageing over lees (Palomero et al. 2009; Domizio et al. 2017). Previous studies have demonstrated a positive effect of polysaccharides on the quality and sensorial properties of wine (Vidal et al. 2004; Gawel et al. 2014). Polysaccharides affect mouth-feel properties such as fullness, while reducing the astringency of the final product (Vidal et al. 2004) and contribute to the retention of positive aroma compounds (Lubbers et al. 1994).

The technology based on the use of Lachancea and Schizosaccharomyces genera was studied before for simple fermentation parameters (Benito et al. 2015a). During the last year, more advanced parameters such as volatile compounds, amino acids, biogenic amines (Benito et al. 2016b) and anthocyanin composition (Benito et al. 2017) have also been studied. However, several additional fermentation factors require to be researched for this modern technology, and to this end, our research focus on the effect of Lachancea and Schizosaccharomyces genera on wine mannose-containing polysaccharides release during alcoholic fermentation.

Materials and methods

Microbiological material

The yeast strains selected for the trials were: Kluyveromyces thermotolerans Concerto™ (Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark), S. cerevisiae CECT 87 (Type Culture Collection of Spain, Valencia University, Spain) and a pre-commercial S. pombe V2 [GenBank accession number HE963293; also deposited and publicly available in the Chemistry and Food Technology Department Yeast Collection of Polytechnic University of Madrid; Benito et al. (2014)]. The selected lactic acid bacteria strain was O. oeni 217 (Type Culture Collection of Spain, Valencia University, Spain).

Vinification

The experimental vinifications took place at a scale according to previously described microvinification methodology (Sampaio et al. 2007), which was modified (Belda et al. 2015; Benito et al. 2015a, b). Tempranillo grape must (Rioja Alta, Spain) was used with 226 g/L sugar, pH = 3.61, PAN 333 mg/L, malic acid was 2.54 g/L and citric acid was 030 g/L. Lactic and acetic acids were 0.01 g/L.

Fermentations took place in 5 L vessels where 4 L of must fermented in triplicate for each treatment. The free run Tempranillo must after being destemmed and crushed was autoclaved at 105 °C for 5 min. The initial inoculum concentration for the different treatments were S. cerevisiae alone (106 cfu/mL) (SC), L. thermotolerans (106 cfu/mL) and S. cerevisiae (106 cfu/mL) 72 h later (LT…SC), L. thermotolerans (106 cfu/mL) and S. pombe (106 cfu/mL) 72 h later (LT…SK) and S. pombe alone (106 cfu/mL) (SK). The alcoholic fermentations took place at controlled temperature of 25 °C. Fermentations regarding S. cerevisiae alone (SC) were inoculated with O. oeni (107 cfu/mL) and performed malolactic fermentation in 2.8 L vessels at 18 °C. Once fermentations were over the wines were racked into small vessels of 2.8 L where they settled at 4 °C for 7 days. After that period, the supernatant was introduced into 750 mL bottles where 100 mg/L of potassium metabisulfite (Agrovin S.A, Alcazar de San Juan, Spain) were added. The bottles were sealed and stayed horizontally in a refrigerator at 4 °C. The sensory session took place 58 days after the last fermentation ended.

Biochemical compounds

The quantification of parameters showed in Table 1 were performed using the method described in previous studies (Belda et al. 2015; Benito et al. 2015b). A Y15 Autoanalyser (Biosystems, Barcelona, Spain), a GAB Microebu and a Crison pH meter (Basic 20, Crison Barcelona, Spain) were used.

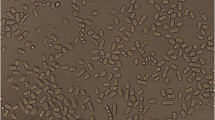

Yeast growth

The changes in the population of the different yeast species (Fig. 1) were studied according to the methodology described by Benito et al. (2015b), which is based on the use of selective-differential media such as YEPDAactBzCL Schizosaccharomyces selective media (Benito et al. 2018), lysine media (Morris and Eddy 1957), YEPD media (Kurtzman et al. 2011) and MRS agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Schizosaccharomyces selective media allows monitoring Schizosaccharomyces colonies, lysine media allows to detect some non-Saccharomyces yeasts such as L. thermotolerans, YEPD media alows to detect any wine yeast species and MRS agar allows monitoring lactic bacteria.

Change in the population of S. cerevisiae 87 alone (SC), sequential fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae 87 and L. thermotolerans CONCERTO™ (LT…SC), sequential fermentation with S. pombe V2 and Lachancea thermotolerans CONCERTO™ (LT…SK) and S. pombe V2 alone (SK). Values are means ± standard (logCFU/mL) deviations for three independent fermentations

Determination of mannose

Mannose content of the total soluble wine polysaccharides was evaluated according to the methodology described by Belda et al. (2016).

Sensory analysis

The final wines were assessed in a blind tasting by a panel of 15 experienced wine tasters, all staff members of the Chemistry and Food Technology Department of Polytechnic University of Madrid (Madrid, Spain) and the Accredited Laboratory Estación Enológica de Haro (Haro, Spain). The sensory analysis was similar to that described in previous works (Belda et al. 2015, 2016; Benito et al. 2017). In this study, 14 attributes were established by consensus (Fig. 3).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using PC Statgraphics v.5 software (Graphics Software Systems, Rockville, MD, USA). The significance was set to p < 0.05 for the ANOVA matrix F value. A multiple range test was used to compare the means.

Results

Fermentation performance

Figure 1 shows the yeast counts during the different fermentations. S. cerevisiae and S. pombe cells remained constant until the conclusion of fermentation in concentrations that varied from 8.4 × 105 to 6.1 × 106 cfu/mL. L. thermotolerans cell counts decreased after day 5.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe degraded all malic acid (Table 1) during alcoholic fermentation (AF) in pure and mixed modalities, while S. cerevisiae degraded malic acid only to about 5% (Table 1). O. oeni converted the remaining malic acid into lactic acid to obtain stable wines in trials fermented by S. cerevisiae (Table 1). L. thermotolerans synthetized l-lactic acid during AF (Table 1). The final l-lactic acid concentrations varied from 1.46 g/L for the case fermented by S. cerevisiae and O. oeni, to 3.11 g/L for the case fermented by L. thermotolerans, S. cerevisiae and O. oeni. The final pH varied from 3.47 to 3.91 g/L due to malic and lactic acid metabolism. Wines produced with S. pombe had a pyruvic acid concentrations of 168 mg/L and a glycerol concentration of about 7.78 g/L. The reported acetic acid concentrations were below 0.4 g/L. Ethanol concentrations varied from 13.55 to 13.80% (v/v). Wines produced with S. pombe had slightly lower ethanol concentration of 0.23% (v/v) than S. cerevisiae (control) wines. Fermentations involving S. pombe resulted in final urea concentrations lower than 0.1 mg/L (Table 1). The fermentations, which did not involve S. pombe, showed final urea concentrations of about 2 mg/L. Urea concentration increased from 0.2 to 0.3 g/L after malolactic fermentation (MLF). Malolactic fermentations performed by O. oeni showed final citric acid concentrations of 0.04 mg/L and below (Table 1). Slightly higher acetic acid concentrations were found in wines that underwent MLF. Those increases varied from 0.09 to 0.11 g/L.

Figure 2 shows the content of mannose after the fermentations and cold sedimentation. S. cerevisiae and L. thermotolerans release mannose from mannoproteins while S. pombe release it from galactomannoproteins. The highest increase in mannose took place in the fermentations where S. pombe fermented alone. The final concentration was about 250 mg/L of mannose released from polysaccharides after hydrolysis. The sequential fermentations involving L. thermotolerans and S. pombe showed a significant increase in mannose, compared to S. cerevisiae fermentations only. The final difference was about 100 mg/L in mannose.

Mannose released from polysaccharides after hydrolysis of wines fermented at microvinification scale with: S. cerevisiae 87 alone (SC), sequential fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae 87 and L. thermotolerans CONCERTO™ (LT…SC), sequential fermentation with S. pombe V2 and Lachancea thermotolerans CONCERTO™ (LT…SK), S. pombe V2 alone (SK), and fermentations after malolactic fermentation with Oenococcus oeni 217 (+MLF)

Sensory evaluation

Figure 3 shows a radar graph of the scores of various attributes. It shows differences in the perception of acidity, as several microorganisms are able to affect acidity. Color intensity was higher in wines produced without malolactic fermentation, compared to wines that underwent malolactic fermentation. None of the wines that were produced with S. pombe or L. thermotolerans showed any negative organoleptic properties. Significant differences in mouth volume, persistence, structure and aroma were evident between the different treatments (Fig. 3). Sequential fermentations by Schizosaccharomyces and Lachancea obtained the maximum mark in overall impression.

Results of the sensory analysis of bottled wines from different fermentation processes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 87 alone (SC), sequential fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae 87 and L. thermotolerans CONCERTO™ (LT…SC), sequential fermentation with S. pombe V2 and L. thermotolerans CONCERTO™ (LT…SK), S. pombe V2 alone (SK), and fermentations after malolactic fermentation with Oenococcus oeni 217 (+MLF)

Discussion

Fermentation performance

Certain authors describe L. thermotolerans as a yeast not able to complete fermentation when the final alcohol levels are between 9 and 10% (Lubbers et al. 1994; Kapsopoulou et al. 2005; Benito et al. 2016b). For this reason, L. thermotolerans should be used in combination with yeast genera such as Saccharomyces or Schizosaccharomyces to complete the fermentation process (Benito et al. 2015a; Balikci et al. 2016). The combine AF finished the fermentations as the glucose/fructose concentrations were lower than 2 g/L (Table 1).

Other studies described L-lactic acid production of up to 6 g/L when Lachancea was utilized in pure fermentation (Gobbi et al. 2013; Benito et al. 2015b, 2016b). l-Lactic acid concentrations were higher in wines where grape juice was inoculated with L. thermotolerans where wines underwent MLF (O. oeni). This is a useful strategy to increase the acidity of wines from grapes originating from warm regions which usually have a low acidity (Benito et al. 2018).

The increase in acetic acid concentrations could be due to citric acid consumption of O. oeni during MLF. Other authors reported high levels of acetic acid as a possible collateral effect when MLF occurs without proper control (Mylona et al. 2016). The increases of about 0.1 g/L in acetic acid after MLF observed in this study support those theories (Table 1). Work by Comitini et al. (2011) and Gobbi et al. (2013) reported that L. thermotolerans produced lower concentrations of acetic acid than S. cerevisiae (Miljic et al. 2017) with differences varying between 0.18 and 0.33 g/L. In contrast to the above, the genus Schizosaccharomyces often produce acetic acid concentrations over 0.9 g/L (Mylona et al. 2016). Nevertheless, recent studies on Schizosaccharomyces showed that specific strains produce acetic acid only as low as 0.1 g/L (Domizio et al. 2017; Du Plessis et al. 2017; Roca-Domènech et al. 2018). Fleet (2008) proposed the selection of a Schizosaccharomyces strain to prevent conventional co-fermentation effects attributed to this genus, such as high acetic acid production. The final observed acetic acid concentration in the fermentations regarding S. pombe of about 0.35 g/L support the theories related to strain variability. The use of S. pombe under reduced osmotic stress conditions afforded by fed-batch alcoholic fermentation also allows the production of wines with low levels in acetic acid (Roca-Domènech et al. 2018).

Domizio et al. (2017) found concentrations of up to 430 mg/L pyruvic acid in wines made with Schizosaccharomyces. However, the pyruvic acid was measured 5 days after fermentation started when it reached maximum concentration during AF. Increased pyruvic acid formation is associated with increased concentrations of stable color pigments which can improve wine color (Benito et al. 2017; Benito 2018). In this study, the pure S. pombe fermentation produced 66% more pyruvic acid than the S. cerevisiae control. The mixed fermentation between L. thermotolerans and S. pombe showed a final pyruvic acid concentration of 50% higher than the S. cerevisiae control.

Non-Saccharomyces yeasts are one of the main contributors of glycerol content to wine quality (Jolly et al. 2006, 2014; Goold et al. 2017). Domizio et al. (2017) reported the production of glycerol of up to 11.4 g/L by certain strains of by Schizosaccharomyces. In this study the increases in glycerol produced by the non-Saccharomyces were moderated. In the case of S. pombe the increase was 0.66 g/L higher than the S. cerevisiae control, while in the case of the mixed fermentation between L. thermotolerans and S. pombe the increase was only of 0.27 g/L higher.

Schizosaccharomyces is tolerant to ethanol stress environments (Garcia et al. 2016). Other studies related to L. thermotolerans (Gobbi et al. 2013) and S. pombe (Benito et al. 2013) reported similar results. Although the ethanol concentration (Table 1) were significantly different, the differences were lower than 0.25% (v/v). Ethanol reduction higher than 1% (v/v) appear to be related to conditions of increased aeration (Contreras et al. 2015; Morales et al. 2015), or specific enzyme activity such as glucose oxidase or catalase (Rocker et al. 2016). These methodologies can be applied to avoid difficult fermentations of grape must with a high sugar concentration. In those cases, it is difficult for regular yeasts to convert all sugars into ethanol.

The enzymatic urease ability of S. pombe is valuable for producing wines free of ethyl carbamate (Mylona et al. 2016), which is important from a food safety point of view as ethyl carbamate is considered to be a carcinogenic hazard. In this study the fermentations where S. pombe was involved showed urea levels 97% lower than the controls. As urea is the main precursor of ethyl carbamate in wine (Benito et al. 2016c), the wines that showed final urea concentrations close to 0 mg/L look to be virtually stable against future ethyl carbamate production.

Mannose-containing polysaccharides content in fermentations

The increase of mannoprotein concentrations during AF is a modern approach to improve wine quality (Domizio et al. 2014). Domizio et al. (2017) reported on the special ability of the Schizosaccharomyces genus to release high amounts of polysaccharides. S. pombe releases galactomannoproteins instead of mannoproteins (Domizio et al. 2017). Those galactomannoproteins contains a higher content in mannose ranging from 44 to 47% than galactose, that ranges from 36 to 45% for the case of S. pombe (Domizio et al. 2017). On the other hand, L. thermotolerans is a moderate mannoprotein producer when compared to S. cerevisiae (Belda et al. 2016). Non-Saccharomyces species such as T. delbrueckii also produce higher concentrations of mannoproteins when compared to S. cerevisiae during AF (Belda et al. 2015). The results of this study show higher release of mannose in all fermentations involving S. pombe (Fig. 2). This indicates a higher mannose-containing polysaccharides release during the alcoholic fermentation.

Sensory evaluation

The high color intensity of wines of non-MLF is in agreement with previous work by Mylona et al. (2016) that found significant anthocyanin concentration decreases through lactic acid bacteria metabolism. L. thermotolerans metabolism improves wine color intensity due to the production of lactic acid thereby decreasing the pH (Benito 2018) while S. pombe producers high concentrations of vitisins or pyranoanthocyanins (Benito et al. 2017; Benito 2018). Mannoproteins can also increase the anthocyanins in wine (Vidal et al. 2003).

According to works by Vidal et al. (2004) and Gawel et al. (2014), factors related to mouth-feel properties such as fullness sensation or perceived viscosity, are dependent on polysaccharides concentrations. This is in agreement with mannose-containing polysaccharides levels reported in this study that showed high scores of mouth-feel properties such as structure or mouth volume (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Although the structure was similar in all fermentations involving S. pombe, sequential fermentations by L. thermotolerans and S. pombe obtained the maximum mark in overall impression due to a better balance between acidity and structure. Differences in aroma quality could be related to the ability of the mannoprotein to retain positive aroma compounds such as B-ionone (Lubbers et al. 1994) or the ability of L. thermotolerans to generate high levels of aromatic esters (Benito et al. 2015b).

The combination of S. pombe and L. thermotolerans as a new winemaking biotechnology is able to improve wine quality under specific conditions. It is a substitute to the conventional MLF, which increases mannose-containing polysaccharides of wine and maintain a balance between wine structure and acidity. The results of the fermentation trials showed positive differences in acetic acid, urea, pyruvic acid and glycerol concentrations as well as sensory attributes. The proposed inoculation combination could improve wine aging aptitude as it reduces the pH and prevents possible collateral effects such as the formation of biogenic amines or ethyl carbamate.

Abbreviations

- S. cerevisiae or SC:

-

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- S. pombe or SK:

-

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

- L. thermotolerans or LT:

-

Lachancea thermotolerans

References

Balikci E, Tanguler H, Jolly NP, Erten H (2016) Influence of Lachancea thermotolerans on cv. Emir wine fermentation. Yeast 33:313–321

Belda I, Navascues E, Marquina D, Santos A, Calderon F, Benito S (2015) Dynamic analysis of physiological properties of Torulaspora delbrueckii in wine fermentations and its incidence on wine quality. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:1911–1922

Belda I, Navascues E, Marquina D, Santos A, Calderon F, Benito S (2016) Outlining the influence of non-conventional yeasts in wine ageing over lees. Yeast 33:329–338

Benito S (2018) The impacts of Lachancea thermotolerans yeast strains on winemaking. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102(16):6775–6790

Benito S, Palomero F, Morata A, Calderón F, Palmero D, Suárez-Lepe JA (2013) Physiological features of Schizosaccharomyces pombe of interest in making of white wines. Eur Food Res Technol 236:29–36

Benito S, Palomero F, Calderón F, Palmero D, Suárez-Lépe J (2014) Selection of appropriate Schizosaccharomyces strains for winemaking. Food Microbiol 42:218–224

Benito A, Calderon F, Palomero F, Benito S (2015a) Combine use of selected Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Lachancea thermotolerans yeast strains as an alternative to the traditional malolactic fermentation in red wine production. Molecules 20:9510–9523

Benito S, Hofmann T, Laier M, Lochbühler B, Schüttler A, Ebert K, Fritsch S, Röcker J, Rauhut D (2015b) Effect on quality and composition of Riesling wines fermented by sequential inoculation with non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur Food Res Technol 241:707–717

Benito Á, Calderón F, Benito S (2016a) Combined use of S. pombe and L. thermotolerans in winemaking. Beneficial effects determined through the study of wines analytical characteristics. Molecules 21:1744

Benito A, Calderon F, Palomero F, Benito S (2016b) Quality and composition of Airen wines fermented by sequential inoculation of Lachancea thermotolerans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Technol Biotechnol 54:135–144

Benito Á, Jeffares D, Palomero F, Calderón F, Bai FY, Bähler J, Benito S (2016c) Selected Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains have characteristics that are beneficial for winemaking. PLoS ONE 11:e0151102

Benito A, Calderon F, Benito S (2017) The combined use of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Lachancea thermotolerans-effect on the anthocyanin wine composition. Molecules 22:739

Benito A, Calderon F, Benito S (2018) Schizosaccharomyces pombe isolation protocol. In: Singleton TL (ed) Methods molecular biology, chapter 20. Springer, Berlin, pp 227–234

Comitini F, Gobbi M, Domizio P, Romani C, Lencioni L, Mannazzu I, Ciani M (2011) Selected non-Saccharomyces wine yeasts in controlled multistarter fermentations with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiol 28:873–882

Contreras A, Curtin C, Varela C (2015) Yeast population dynamics reveal a potential ‘collaboration’ between Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Saccharomyces uvarum for the production of reduced alcohol wines during Shiraz fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:1885–1895

Domizio P, Liu Y, Bisson LF, Barile D (2014) Use of non-Saccharomyces wine yeasts as novel sources of mannoproteins in wine. Food Microbiol 43:5–15

Domizio P, House JF, Joseph CML, Bisson LF, Bamforth CW (2016) Lachancea thermotolerans as an alternative yeast for the production of beer. J Inst Brew 122:599–604

Domizio P, Liu Y, Bisson LF, Barile D (2017) Cell wall polysaccharides released during the alcoholic fermentation by Schizosaccharomyces pombe and S. japonicus: quantification and characterization. Food Microbiol 61:136–149

Du Plessis H, Du Toit M, Hoff J, Hart R, Ndimba B, Jolly N (2017) Characterisation of non-Saccharomyces yeasts using different methodologies and evaluation of their compatibility with malolactic fermentation. S Afr J Enol Vitic 38:46–63

Escribano R, Gonzalez-Arenzana L, Portu J, Garijo P, Lopez-Alfaro I, Lopez R, Santamaria P, Gutierrez AR (2018) Wine aromatic compound production and fermentative behaviour within different non-Saccharomyces species and clones. J Appl Microbiol 124(6):1521–1531

Fleet GH (2008) Wine yeasts for the future. FEMS Yeast Res 8:979–995

Garcia M, Greetham D, Wimalasena TT, Phister TG, Cabellos JM, Arroyo T (2016) The phenotypic characterization of yeast strains to stresses inherent to wine fermentation in warm climates. J Appl Microbiol 121:215–233

Gawel R, Day M, Van Sluyter SC, Holt H, Waters EJ, Smith PA (2014) White wine taste and mouthfeel as affected by juice extraction and processing. J Agric Food Chem 62:10008–10014

Gobbi M, Comitini F, Domizio P, Romani C, Lencioni L, Mannazzu I, Ciani M (2013) Lachancea thermotolerans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in simultaneous and sequential co-fermentation: a strategy to enhance acidity and improve the overall quality of wine. Food Microbiol 33:271–281

Goold HD, Kroukamp H, Williams TC, Paulsen IT, Varela C, Pretorius IS (2017) Yeast’s balancing act between ethanol and glycerol production in low-alcohol wines. Microb Biotechnol 10:264–278

Jolly J, Augustyn O, Pretorius I (2006) The role and use of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in wine production. S Afr J Enol Vitic 27:15–39

Jolly NP, Varela C, Pretorius IS (2014) Not your ordinary yeast: non-Saccharomyces yeasts in wine production uncovered. FEMS Yeast Res 14:215–237

Kapsopoulou K, Kapaklis A, Spyropoulos H (2005) Growth and fermentation characteristics of a strain of the wine yeast Kluyveromyces thermotolerans isolated in Greece. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 21:1599–1602

Kapsopoulou K, Mourtzini A, Anthoulas M, Nerantzis E (2007) Biological acidification during grape must fermentation using mixed cultures of Kluyveromyces thermotolerans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 23:735–739

Kurtzman CP, Fell JW, Boekhout T, Robert V (2011) Methods for isolation, phenotypic characterization and maintenance of yeasts. In: Kurtzman CP, Fell JW, Boekhout T, Robert V (eds) The yeasts, a taxonomic study. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 87–110

Lubbers S, Voilley A, Feuillat M, Charpentier C (1994) Influence of mannoproteins from yeast on the aroma intensity of a model wine. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und-Technologie 27:108–114

Miljic U, Puskas V, Vucurovic V, Muzalevski A (2017) Fermentation characteristics and aromatic profile of plum wines produced with indigenous microbiota and pure cultures of selected yeast. J Food Sci 82:1443–1450

Minnaar PP, Jolly NP, Paulsen V, Du Plessis HW, Van Der Rijst M (2017) Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts in sequential fermentations: effect on phenolic acids of fermented Kei-apple (Dovyalis caffra L.) juice. Int J Food Microbiol 257:232–237

Morales P, Rojas V, Quiros M, Gonzalez R (2015) The impact of oxygen on the final alcohol content of wine fermented by a mixed starter culture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:3993–4003

Morris E, Eddy A (1957) Method for the measurement of wild yeast infection in pitching yeast. J Inst Brew 63:34–35

Mylona AE, Del Fresno JM, Palomero F, Loira I, Banuelos MA, Morata A, Calderon F, Benito S, Suarez-Lepe JA (2016) Use of Schizosaccharomyces strains for wine fermentation-effect on the wine composition and food safety. Int J Food Microbiol 232:63–72

Nally M, Ponsone L, Pesce V, Toro M, Vazquez F, Chulze S (2018) Evaluation of behavior of Lachancea thermotolerans biocontrol agents on grape fermentations. Lett Appl Microbiol 67(1):89–96

Padilla B, Gil JV, Manzanares P (2016) Past and future of non-Saccharomyces yeasts: from spoilage microorganisms to biotechnological tools for improving wine aroma complexity. Front Microbiol 7:411

Palomero F, Morata A, Benito S, Calderón F, Suárez-Lepe JA (2009) New genera of yeasts for over-lees aging of red wine. Food Chem 112(2):432–441

Peinado RA, Maestre O, Mauricio JC, Moreno JJ (2009) Use of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe mutant to reduce the content in gluconic acid of must obtained from rotten grapes. J Agric Food Chem 57:2368–2377

Roca-Domènech G, Cordero-Otero R, Rozès N, Cléroux M, Pernet A, Orduña RM (2018) Metabolism of Schizosaccharomyces pombe under reduced osmotic stress conditions afforded by fed-batch alcoholic fermentation of white grape must. Food Res Int 113:401–406

Rocker J, Schmitt M, Pasch L, Ebert K, Grossmann M (2016) The use of glucose oxidase and catalase for the enzymatic reduction of the potential ethanol content in wine. Food Chem 210:660–670

Sampaio TL, Kennedy JA, Vasconcelos MC (2007) Use of microscale fermentations in grape and wine research. Am J Enol Vitic 58:534–539

Satora P, Semik-Szczurak D, Tarko T, Buldys A (2018) Influence of selected Saccharomyces and Schizosaccharomyces strains and their mixed cultures on chemical composition of apple wines. J Food Sci 83:424–431

Varela C (2016) The impact of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in the production of alcoholic beverages. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:9861–9874

Vidal S, Williams P, Doco T, Moutounet M, Pellerin P (2003) The polysaccharides of red wine: total fractionation and characterization. Carbohydr Polym 54:439–447

Vidal S, Francis L, Williams P, Kwiatkowski M, Gawel R, Cheynier V, Waters E (2004) The mouth-feel properties of polysaccharides and anthocyanins in a wine like medium. Food Chem 85:519–525

Authors’ contributions

ÁB carried out all the experimental work and participated in the experimental design. FC supported the experimental work, participated in project conception and provided critical review of the manuscript. SB supported the experimental work, participated in the experimental design and coordinated the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the accredited Estación Enológica de Haro Laboratory for their support, especially to Montserrat Iñiguez and Elena Melendez. The Funding of this research was supported by Ossian Vides y Vinos S.L. The researching Project Number is FPA1720300120 (CDTI, Spain).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests and certify that there is no competing interests with any financial or non-financial organization regarding the contents of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable (all data are included in the manuscript).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Written in Acknowledgements section.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Benito, Á., Calderón, F. & Benito, S. Mixed alcoholic fermentation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Lachancea thermotolerans and its influence on mannose-containing polysaccharides wine Composition. AMB Expr 9, 17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0738-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0738-0