Abstract

Since fossil sources for fuel and platform chemicals will become limited in the near future, it is important to develop new concepts for energy supply and production of basic reagents for chemical industry. One alternative to crude oil and fossil natural gas could be the biological conversion of CO2 or small organic molecules to methane via methanogenic archaea. This process has been known from biogas plants, but recently, new insights into the methanogenic metabolism, technical optimizations and new technology combinations were gained, which would allow moving beyond the mere conversion of biomass. In biogas plants, steps have been undertaken to increase yield and purity of the biogas, such as addition of hydrogen or metal granulate. Furthermore, the integration of electrodes led to the development of microbial electrosynthesis (MES). The idea behind this technique is to use CO2 and electrical power to generate methane via the microbial metabolism. This review summarizes the biochemical and metabolic background of methanogenesis as well as the latest technical applications of methanogens. As a result, it shall give a sufficient overview over the topic to both, biologists and engineers handling biological or bioelectrochemical methanogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methanogens are biocatalysts, which have the potential to contribute to a solution for future energy problems by producing methane as storable energy carrier. The very diverse archaeal group of methanogens is characterized by the ability of methane production (Balch et al. 1979). The flammable gas methane is considered to be a suitable future replacement for fossil oil, which is about to be depleted during the next decades (Ren et al. 2008). Methane can be used as a storable energy carrier, as fuel for vehicles, for the production of electricity, or as base chemical for synthesis and many countries do already have well developed natural gas grids (Ren et al. 2008). In terms of the necessary transition from chemical to biological processes, methanotrophic bacteria can use methane as a carbon and energy source to produce biomass, enzymes, PHB or methanol (Strong et al. 2015; Ge et al. 2014). The biological methanation is the main industrial process involving methanogens. These archaea use CO2 and H2 and/or small organic molecules, such as acetate, formate, and methylamine and convert it to methane. Although the electrochemical production of methane is still more energy efficient than the biological production [below 0.3 kWh/cubic meter of methane (0.16 MPa, Bär et al. 2015)], the biological conversion may be advantageous due to its higher tolerance against impurities (H2S and NH3) within the educt streams, especially if CO2 rich waste gas streams shall be used (Bär et al. 2015). Apart from that, research is going on to increase the energy efficiency of the biological process, so that it might be the preferred way of methane production in the future (Bär et al. 2015). Biological methanation occurs naturally in swamps, digestive systems of animals, oil fields and other environments (Garcia et al. 2000) and is already commonly used in sewage water plants and biogas plants. New applications for methanogens such as electromethanogenesis are on the rise, and yet, there is still a lot of basic research, such as strain characterization and development of basic genetic tools, going on about the very diverse, unique group of methanogens (Blasco-Gómez et al. 2017). This review will summarize important facts about the biological properties and possibilities of genetic modification of methanogenic organisms as well as the latest technical applications. It shall therefore give an overview over the applicability of methanogens and serve as a start-up point for new technical developments.

Biochemical and microbial background

Methanogens are the only group of microorganisms on earth producing significant amounts of methane. They are unique in terms of metabolism and energy conservation, are widespread in different habitats and show a high diversity in morphology and physiological parameters.

Phylogeny and habitats of methanogens

For decades known methanogenic archaea belonged exclusively to the phylum Euryarchaeota. There, methanogens were classified first into five orders, namely Methanococcales, Methanobacteriales, Methanosarcinales, Methanomicrobiales and Methanopyrales (Balch et al. 1979; Stadtman and Barker 1951; Kurr et al. 1991). Between the years 2008 and 2012 another two orders of methanogens, namely Methanocellales (Sakai et al. 2008) and Methanomassiliicoccales (Dridi et al. 2012; Iino et al. 2013), were added to the phylum Euryarchaeota. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis from H2 and CO2 is found in almost all methanogenic orders with the exception of the Methanomassiliicoccales. Due to its broad distribution it is postulated that this type of methanogenesis is the ancestral form of methane production (Bapteste et al. 2005). Methane formation from acetate, called aceticlastic methanogenesis, can be found only in the order Methanosarcinales. In contrast to that, methylotrophic methanogenesis, which is the methane formation from different methylated compounds such as methanol, methylamines or methylated thiols, is found in the orders Methanomassiliicoccales, Methanobacteriales and Methanosarcinales. Extensive recent metagenomic analyses suggested that methanogens may no longer restricted to the Euryarchaeota. Two new phyla, namely the Bathyarchaeota (Evans et al. 2015) and the Verstraetearchaeota (Vanwonterghem et al. 2016) were postulated. Genome sequences from both phyla indicate a methylotrophic methane metabolism in these -as of yet uncultivated- potential methanogens.

Methanogens are a relative diverse group of archaea and can be found in various anoxic habitats (Garcia et al. 2000). For example, they can be cultured from extreme environments such as hydrothermal vents or saline lakes. Methanocaldococcus jannaschii was isolated from a white smoker chimney of the East Pacific Rise at a depth of 2600 m (Jones et al. 1983) and Methanopyrus kandleri from a black smoker chimney from the Gulf of California in a depth of 2000 m (Kurr et al. 1991). From a saline lake in Egypt the halophilic methanogen Methanohalophilus zhilinae was cultured (Mathrani et al. 1988). But methanogens also colonize non-extreme environments. They can be isolated from anoxic soil sediments such as rice fields, peat bogs, marshland or wet lands. For example, Methanoregula boonei was obtained from an acidic peat bog (Bräuer et al. 2006, 2011) and several strains of Methanobacterium as well as Methanosarcina mazei TMA and Methanobrevibacter arboriphilus were isolated from rice fields (Asakawa et al. 1995).

Some methanogens can also associate with plants, animals and could be found in the human body. Methanobacterium arbophilicum could be isolated from a tree wetwood tissue and uses the H2 resulting from pectin and cellulose degradation by Clostridium butyricum for methanogenesis (Schink et al. 1981; Zeikus and Henning 1975). From the feces of cattle, horse, sheep and goose the methanogens Methanobrevibacter thaueri, Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii, Methanobrevibacter wolinii and Methanobrevibacter woesei have been isolated, respectively (Miller and Lin 2002). In addition, different Methanobrevibacter species could be found in the intestinal tract of insects such as termites (Leadbetter and Breznak 1996). Beside the intestinal tract of herbivorous mammals also the rumen contains methanogens. One of the major species here is Methanobrevibacter ruminantium (Hook et al. 2010). Methanogenic archaea are also present in the human body. Methanobrevibacter smithii and Methanosphaera stadtmanae as well as Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis could be detected in human feces (Dridi et al. 2009, 2012; Miller et al. 1982). Further Methanosarcina sp., Methanosphaera sp. and Methanobrevibacter oralis were discovered in human dental plaque (Belay et al. 1988; Ferrari et al. 1994; Robichaux et al. 2003).

Methanogens can be also found in non-natural habitats such as landfills, digesters or biogas plants. There, the microbial community varies with the substrate. In biogas plants, due to hydrolysis of complex polymers to sugars and amino acids, followed by fermentation and acetogenesis, acetate, H2 and CO2 is produced as substrates for methanogenesis. Therefore, hydrogenotrophic and aceticlastic methanogens are prevalent in mesophilic biogas plants, often dominated by species of Methanosarcina (Methanothrix at low acetate concentrations) or Methanoculleus (Kern et al. 2016b; Karakashev et al. 2005; Lucas et al. 2015; Sundberg et al. 2013). However, under certain conditions syntrophic acetate oxidation may be the dominant path towards methane (Schnürer and Nordberg 2008; Westerholm et al. 2016).

Diversity of methanogens in morphology and physiological parameters

Methanogens show not only a wide diversity in regard to their habitats but are also highly diverse in terms of morphology, temperature optimum, pH and osmolarity. The shapes of methanogens (only some typical methanogens are mentioned here) can be coccoid as for Methanococcus, Methanosphaera or Methanococcoides, long or short rods as for Methanobacterium or Methanobrevibacter, or rods in chains as for Methanopyrus (Kurr et al. 1991). Methanoplanus (Ollivier 1997) has a plate-shaped morphology and Methanospirillium (Zeikus and Bowen 1975), as the name says, a spirally shape. Methanosarcina (Balch et al. 1979; Bryant and Boone 1987; Kern et al. 2016a; Mah 1980) are irregularly shaped cocci, most often arranged to sarcina cell packages. In addition long filaments formed with rods were observed by species of Methanothrix [formerly designated Methanosaeta (Kamagata et al. 1992)]. The formation of multicellular aggregates irrespective of the individual cell shape can also occur, like for species of Methanolobus (Mochimaru et al. 2009), Methanosarcina (Kern et al. 2016a), or Methanobacterium (Kern et al. 2015).

The diversity of methanogens is also reflected in the different growth conditions. Many methanogens have a mesophilic temperature spectrum, as, e.g. Methanosarcina, Methanobacterium, or most Methanococcus. However, thermophilic and even hyperthermophilic methanogens are known, like Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus or M. jannaschii which grow at temperatures of up to 75 and 86 °C, respectively. Even growth up to 110 °C is possible in hot environments as shown for the hyperthermophilic strain M. kandleri (Kurr et al. 1991). In contrast, also cold-loving methanogenic strains could be isolated. One example is the methanol-converting archaeon Methanolobus psychrophilus, which grows optimally at 18 °C and shows still metabolic activity at 0 °C (Zhang et al. 2008).

Beside the temperature, salt concentration may also be an important physiological parameter for methanogens. A few methanogens have colonized niches such as saline lakes, which are extreme environments for microorganisms because of their high salinity. Microorganisms living under such salty conditions have to protect themselves from losing water and “salting-out”. Due to the fact that biological membranes are permeable to water, a higher solute concentration outside the cell, as in the case of environments with a high salinity, would drag water out of the cell and would lead to cell death. To prevent the loss of water, and as a countermeasure, microbes increase the cytoplasmatic osmolarity to survive in such salty environments. This can be done in two ways. The first is the synthesis and accumulation of osmoprotectants, also known as compatible solutes, which have a small molecular mass and a high solubility. This has been shown for example for M. mazei. At a NaCl concentration of 400 mM the methanogen synthesizes glutamate in response to hypersalinity. At higher salt concentration (800 mM NaCl) N-acetyl-β-lysine is synthesized in addition to glutamate (Pflüger et al. 2005, 2003). But N-acetyl-β-lysine is not essential for growth and can be also substituted by glutamate and alanine at high salinity (Saum et al. 2009). Moreover it has been also shown that M. mazei can take up the osmoprotectant glycine betaine from its environment (Roeßler et al. 2002). The second way to protect the cell from loosing water, and to balance the cytoplasm osmotically with the high salinity of the environment, is an influx of potassium and chloride into the cytoplasm (Oren 2008). This as “high-salt-in strategy” known way may be also used by the recently discovered “Methanonatronarchaeia” (Sorokin et al. 2017). They appear to be extremely halophilic, methyl-reducing methanogens related to the haloarchaea.

Although most (by far) methanogens grow optimally around neutral pH, some, which are halophilic or halotolerant, show also an adaptation to alkaline pH. Methanocalculus alkaliphilus grows alkaliphilically with an optimum at pH 9.5 and a moderate salinity up to 2 M of total Na+, whereas Methanosalsum natronophilum can even tolerate higher salinities, up to 3.5 M of total Na+, at the same alkaline pH (Sorokin et al. 2015). Moderately acidic environments can also be inhabited by methanogens as, for example, Methanoregula booneii, which was isolated from an acidic peat bog and has an pH optimum for growth of 5.1 (Bräuer et al. 2006, 2011).

Substrates and metabolism of methanogens

Methanogens use the substrate CO2 and the electron donor H2 during hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. In the first step, CO2 is reduced and activated to formyl-methanofuran (Wagner et al. 2016) in which reduced ferredoxin (Fdred) is the electron donor for this reaction (Fig. 1).

Schematic overview of hydrogenotrophic (a), aceticlastic (b) and methylotrophic (c) methanogenesis. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis for Ech-containing methanogens is shown. The methylotrophic methanogenesis from methanol is displayed. Abbreviations are mentioned in the text

In the second step the formyl group is transferred to tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MTP) obtaining formyl-H4MTP. Then the formyl group is dehydrated and reduced to methylene-H4MTP and subsequently to methyl-H4MTP with reduced F420 (F420H2) as electron donor. The methyl group is then transferred to coenzyme M (HS-CoM). Finally, methyl-CoM is reduced to methane with coenzyme B (HS-CoB) as electron donor. The resulting heterodisulfide (CoM-S-S-CoB) is reduced with H2 to recycle the coenzymes (Liu and Whitman 2008; Thauer et al. 2008). It is also important to note that several methanogens can use formate instead of H2 as electron source for CO2 reduction. There, four formate molecules are first oxidized to CO2 by formate dehydrogenase (Fdh) followed by the reduction of one molecule of CO2 to methane (Liu and Whitman 2008). Instead of H2, a few methanogens can also use alcohols like ethanol or 2-propanol as electron donors (Frimmer and Widdel 1989; Widdel 1986).

Some methanogens can also use carbon monoxide (CO) for methanogenesis. In Methanosarcina barkeri and M. thermautotrophicus four molecules of CO are oxidized to CO2 by CO dehydrogenase (CODH) followed by the reduction of one molecule of CO2 to methane with H2 as electron donor (Daniels et al. 1977; O’Brien et al. 1984). Thus, growth on H2 and CO2 is still possible with both methanogens. In contrast, CO metabolism of Methanosarcina acetivorans seems to be different. It can also use CO, but is unable to grow on H2 and CO2 due to the lack of a functioning hydrogenase system. Further, the organism produces high amounts of acetate and formate from CO during methanogenesis (Rother and Metcalf 2004). The genera Methanosarcina and Methanotrix can use acetate for methane production. In this aceticlastic methanogenesis acetate has to be activated first. It is converted with ATP and coenzyme A (CoA) to acetyl-CoA, which is then split by the CODH/acetyl-CoA synthase complex. The methyl group is transferred to H4MTP [which is tetrahydrosarcinapterin (H4SPT) in Methanosarcina] and further converted to methane like in the CO2 reduction pathway. The carbonyl group is oxidized to CO2, thus providing the electrons for the methyl group reduction (Welte and Deppenmeier 2014).

The third way of biological methanation is methylotrophic methanogenesis in which methylated substrates as methanol, methylamines or methylated sulfur compounds like methanethiol or dimetyl sulfide, are utilized. Most methylotrophic methanogens belong to the Methanosarcinales. In the first step the methyl-group from the methylated substrate is transferred to a corrinoid protein by a substrate-specific methyltransferase (MT1) and subsequently to HS-CoM by another methyltransferase (MT2), thus forming methyl-CoM (Burke and Krzycki 1997). One methyl-CoM is oxidized to CO2 (via the hydrogenotrophic pathway in reverse) generating the reducing equivalents to reduce three methyl-CoM to methane and also generating a proton motive force (Timmers et al. 2017; Welte and Deppenmeier 2014).

Energy conservation in methanogens

In general, methanogens can be divided into two groups according to their mode of energy conservation: methanogens without and with cytochromes (Mayer and Müller 2014; Thauer et al. 2008). Most of the methanogenic archaea do not contain cytochromes. They have a methyl-H4MPT:coenzyme M methyltransferase (Mtr) which couples the methyl group transfer to a primary, electrochemical Na+ gradient over the membrane (Becher et al. 1992; Gottschalk and Thauer 2001). Furthermore, the H2-dependent reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB in cytochrome-free methanogens is catalyzed by a complex consisting of a (methyl viologen-reducing) hydrogenase and heterodisulfide reductase (Mvh-Hdr), which also couples this exergonic process to the concomittant endergonic reduction of oxidized ferredoxin (Fdox) via flavin-based electron bifurcation (Buckel and Thauer 2013). Due to the existence of a Na+ binding motif in the c subunits of A1AO ATP synthases of almost all non-cytochrome containing methanogens (one exception is Methanosalsum zhilinae), the established Na+ gradient can be used for ATP synthesis (Mayer and Müller 2014; Grüber et al. 2014).

Cytochrome-containing methanogens such as M. mazei or M. barkeri, also employ Mtr, thus, generating a Na+ gradient over the membrane. However, reduction of CoM-S-S-CoB is catalyzed by a membrane-bound heterodisulfide reductase (HdrED), which obtains electrons from reduced methanophenazine (MPhH2, functionally analogous to quinoles) via its cytochrome b subunit, which is coupled to the generation of a proton motive force. During hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, a membrane-bound (F420 non-reducing) hydrogenase (Vho) oxidizes H2 and transfers electrons via cytochrome b to oxidized methanophenazine (MPh), again generating a proton motive force. Further, another membranous energy converting hydrogenase, Ech (which is similar to complex I) couples the endergonic reduction of Fdox with H2 to the intrusion of H+, i.e., uses the proton motive force (Mayer and Müller 2014; Thauer et al. 2008; Welte and Deppenmeier 2014). Under environmental conditions, e.g. as in a biogas plants, cytochrome-containing Methanosarcina are outcompeted by “true” hydrogentrophic methanogens, which produce methane from CO2 and H2 exclusively.

Methanosarcina acetivorans lacks both Vho and Ech. Instead it employs an Rnf complex which is thought to establish a Na+ gradient over the membrane by transferring electrons from Fdred (accrued from, e.g., oxidation of CO or oxidation of the carbonyl-group from acetyl-CoA) to MPh. Subsequent electron transport from MPhH2 to HdrED again generates a H+ gradient (Mayer and Müller 2014; Schlegel et al. 2012b; Welte and Deppenmeier 2014).

The fact that methanogenesis in cytochrome-containing methanogens is coupled to the generation of both a H+ and a Na+ gradient (Schlegel and Müller 2013) may be also reflected by the ion dependence of their A1AO ATP synthases. It has been shown that the A1AO ATP synthase from M. acetivorans can use both ion gradients (Schlegel et al. 2012a).

During methylotrophic growth of cytochrome-containing methanogens oxidation to CO2 involves reduction of cofactor F420, which is a 5-deazaflavin derivative. F420H2 is re-oxidized by F420H2 dehydrogenase (Fpo), which is a membrane-bound complex (similar to Nuo of E. coli) and transfers electrons to MPh, thereby establishing a H+ gradient over the membrane in addition to the H+ gradients at Hdr and Ech, and the use of the Na+ gradient at Mtr (Welte and Deppenmeier 2014).

Analyses of genomes from Bathyarchaeota (Evans et al. 2015) and Verstraetearchaeota (Vanwonterghem et al. 2016) suggest a methylotrophic methane metabolism for members of these two new phyla. Reduction of the CoM-S-S-CoB in the Verstraetearchaeota might be accomplished by the Mvh-Hdr complex which might be coupled to re-oxidation of Fdred by an Ehb or and Fpo-like complex. However, what type of ion gradient (H+ and/or Na+) might be established over the membrane, is unclear, although H+ are predicted to be the coupling ion of the respective A1AO ATP synthase (Vanwonterghem et al. 2016). It is obvious that pure culture isolation of Verstraetearchaeota is required in order to address the physiology and energy conservation in these potential methanogens.

In the Bathyarchaeota energy conservation is even more of a mystery. Two available metagenomes, BA1 and BA2 (proposed to be 91.6 and 93.8% complete, respectively), are missing most of the genes encoding for methanogenic energy conservation. Mtr is incomplete, Fpo as well as an energy-converting hydrogenase (like EhaB, establishing a H+ or Na+ gradient over the membrane), are missing. In the genome of BA1 only an Ech hydrogenase is encoded. Also, genes encoding for an A1AO ATP synthase are absent, which would restrict the organism to ATP synthesis by substrate level phosphorylation (SLP) (Evans et al. 2015).

Electroactivity of methanogens

Electron transfer

When electrodes are inserted into a reactor with methanogens, these electrodes can eventually be used by the organisms to produce methane. An external potential leads to the electrolysis of water at the anode; oxygen and protons are produced, electrons are transferred to the anode. Otherwise, excess electrons out of metabolic reactions can be transferred to the anode, like it would happen in a microbial fuel cell. The electrons migrate to the cathode through an external circuit. At the cathode surface, the electrons are transferred to the methanogens, which can use them to produce methane. The complete mechanism is not yet elucidated, but mainly, three possibilities are suggested (Fig. 2) (Sydow et al. 2014; Geppert et al. 2016). Probably, more than one of these mechanisms contributes to the electron transfer (Zhen et al. 2015).

One possible way would be the transfer of electrons from the cathode to protons, which have been produced at the anode and migrated through the membrane between anodic and cathodic chamber. Thereby, hydrogen is produced at the cathode, which is then consumed by the methanogens. This indirect electron transfer (IET) would allow the production of methane out of hydrogen and CO2 (Villano et al. 2010). As an example, IET was observed in M. thermautotrophicus (Hara et al. 2013). It has also been shown that some Methanococcus maripaludis secrete hydrogenases and probably formate dehydrogenases which catalyze the formation of hydrogen and formate directly at the electrode surface; the produced hydrogen and formate is then metabolized by the cells (Deutzmann et al. 2015). This has to be seen as an indirect electron transfer, since the cells were not directly attached to the electrode; from the experimental results, it may be mistaken for a direct electron transport, since the abiotically (without catalyzing hydrogenases) produced amounts of hydrogen and formate cannot explain the amount of methane produced (Deutzmann et al. 2015).

Another possibility suggests that mediator molecules could accept the electrons at the cathode surface, shuttle it to the methanogens and donate it to the microorganisms. This mediated electron transfer (MET) would imply that the methanogens take up electrons, protons and CO2 to form methane (Choi and Sang 2016). Flavins, phenazines or quinones can serve as mediator, either naturally secreted by the organisms or added to the reaction medium (Sydow et al. 2014; Patil et al. 2012). A natural secretion of mediators with a redox potential suitable for microbial electrosynthesis (should be < − 0.4 V vs. SHE) has not been observed yet (Sydow et al. 2014). In methanogens, MET could be performed by using neutral red as an electron shuttle (Park et al. 1999).

The third option would be the direct electron transfer (DET) from the cathode surface to the methanogens, e.g. via surface proteins or conductive filaments (so-called nanowires). To generate methane, the microorganisms would use electrons, protons and CO2 (Cheng et al. 2009). Several studies suggest that direct electron transfer indeed occurs in methanogens (Zhen et al. 2016; Lohner et al. 2014). For a hydrogenase-deficient strain of M. maripaludis hydrogenase-independent electron uptake was demonstrated (Lohner et al. 2014), ruling out IET.

In a mixed microbial consortium, direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) is another possible way of electron transfer. There, one microbial strain takes up electrons at the cathode surface and transfers it to another strain. This may happen, e.g. via conductive filaments (Gorby et al. 2006). It has been reported that this (syntrophic) electron transfer can be very specific between two species, e.g. based on conductive filaments between M. thermautotrophicus and Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum (Gorby et al. 2006) or between M. barkeri and Geobacter metallireducens (Rotaru et al. 2014). Apart from this direct interspecies electron transfer, an interspecies hydrogen transfer can occur. Here, one organisms takes up electrons, produces hydrogen as an intermediate and transfers them to a second organism that forms another product. An example is the defined co-culture between the iron-corroding, sulfate-reducing bacterium ‘Desulfopila corrodens’ IS4 (former name: Desulfobacterium corrodens) for electron uptake and M. maripaludis for methane production (Deutzmann and Spormann 2017).

Electroactive methanogens

Up to date, most investigations on electromethanogenesis have been carried out with mixed cultures, e.g. from wastewater treatment plants, biogas plants or microbial fuel cells. In technical applications, mixed cultures might be more resistant against environmental stress (Babanova et al. 2017), but it is hard to conclude how many and which methanogenic strains are electroactive by themselves. From analysis of the mixed cultures studied, it can be concluded which methanogens are enriched and are therefore likely to be electroactive, although mixed culture experiments cannot replace pure culture studies to prove electroactivity. These are for example Methanobacterium palustre (Cheng et al. 2009; Batlle-Vilanova et al. 2015; Jiang et al. 2014), Methanosarcina thermophila (Sasaki et al. 2013), M. thermautotrophicus (Sasaki et al. 2013; Fu et al. 2015), Methanoculleus thermophilus (Sasaki et al. 2013), Methanobacterium formicicum (Sasaki et al. 2013), M. maripaludis (Deutzmann and Spormann 2017), Methanococcus aeolicus (Feng et al. 2015), M. mazei (Feng et al. 2015), M. arboriphilus (Jiang et al. 2014), Methanocorpusculum parvum (Jiang et al. 2014) and Methanocorpusculum bavaricum (Kobayashi et al. 2013). In other studies, the dominant methanogenic organism has not been defined exactly or not explicitly mentioned (Batlle-Vilanova et al. 2015; Bo et al. 2014; Zhen et al. 2015). Only few studies have been carried out with pure cultures instead of mixed cultures, so these methanogens are the only ones that are certainly electroactive. To mention are M. thermautotrophicus (Hara et al. 2013), and a Methanobacterium-like strain IM1 (Beese-Vasbender et al. 2015).

Yet, just a minority of methanogenic strains has been tested for electroactivity, mostly under similar growth conditions. Unfortunately, no specific marker for electroactivity has been found yet (Koch and Harnisch 2016). It is therefore possible that more electroactive methanogens, active even under more extreme conditions, exist.

Genetic tools for methanogens

Many properties of a (model) organisms are unraveled by biochemical and physiological analysis; however where neither of the two lead to satisfactory insight, genetic analysis is often desirable. Furthermore, the accessibility of an organism relevant for applied purposes to genetic manipulating opens the possibility for targeted engineering by removal of -or amendment with- metabolic or regulatory functions. The principal requirements for such a system are sufficiently efficient methods to (a) isolate clonal populations (e.g., via plating on solid media), to (b) transfer genetic material (i.e., protocols for transformation, transduction, or conjugation), and to (c) link the transfer of the genetic material to an identifiable (i.e., screenable or selectable) phenotype (e.g., conferred by marker genes).

The biochemistry of the methanogenic pathway, the trace elements required, as well as the nature and structure of unusual (C1-carrying) cofactors involved has been elucidated using various Methanobacterium strains (some of them now reclassified as Methanothermobacter). Therefore, it was a logical next step to develop genetic systems for these models. Plating of Methanothermobacter on solid media could be achieved which allowed isolation (and consequently characterization) of randomly induced mutations (Harris and Pinn 1985; Hummel and Böck 1985). However, this species could not be developed into model organisms for genetic analysis because the transfer of genetic material is too inefficient (Worrell et al. 1988). Furthermore, the use of selectable phenotypes was (and still is) restricted because antibiotics (in conjuncture with the respective genes conferring resistance) commonly used in bacterial genetics are ineffective in archaea due to the differences in the target structures (e.g., cell wall, ribosomes). Therefore, the establishing of an antibiotic selectable marker (the pac gene from Streptomyces alboniger conferring resistance to puromycin) in Methanococcus voltae (Gernhardt et al. 1990) was key to the development of gene exchange systems in methanogens. Another feature of Methanococcus, which facilitated method development, is absence of pseudomurein from its cell wall; instead, the organism is surrounded by a proteinacous surface (S-) layer that can be removed with polyethylene glycol (PEG), resulting in protoplasts, which apparently can take up DNA. Combined with its comparably robust and fast growth on H2 + CO2 Methanococcus species, most prominently M. maripaludis, prevailed as the genetic model for hydrogenotrophic methanogens, for which many useful genetic tools have been developed (Table 1, and see Sarmiento et al. 2011 for a review).

For methylotrophic methanogens containing cytochromes (Methanosarcina species) genetic methodology was initially developed on existing tools. PEG-mediated transformation was reported to be ineffective [but later shown to require only modest modifications of the existing protocol (Oelgeschläger and Rother 2009)], but cationic liposomes could be used to transform Methanosarcina species (Metcalf et al. 1997). Like in Methanococcus, presence of an S-layer and availability of an autonomously replicating cryptic plasmid [pC2A in Methanosarcina (Metcalf et al. 1997) and pURB500 in Methanococcus (Tumbula et al. 1997)], which could be engineered into shuttle vectors also replicating in E. coli, made (heterologous) gene expression comparably easy. Markerless insertion and/or deletion of genes was achieved by establishing counter-selective markers, which are used to remove “unwanted” DNA from the chromosome (Pritchett et al. 2004; Moore and Leigh 2005).

Chromosomal integration and deletion of DNA in methanogens, which can be rather inefficient, mostly relies on homologous recombination requiring sequences of substantial length (500–1000 bp) to be cloned. Thus, establishing site-specific recombination by engineering a Streptomyces phage recombination system (\(\Phi {\text{C31}}\)) to integrate DNA into (Guss et al. 2008) -and the yeast Flp/FRT system to remove DNA from- the chromosome (Welander and Metcalf 2008), was a major progress for the genetic manipulation of Methanosarcina. The recent successful -and highly efficient- application of the CRISPR/Cas9-system from Streptococcus pyogenes (Doudna and Charpentier 2014) for gene deletion and insertion in M. acetivorans (Nayak and Metcalf 2017) holds the promise of an even easier way to genetically manipulate these important organisms. Most tools (Table 1) developed for one methanoarchaeal model organism can usually be adapted for use in another, as exemplified by exploiting the insect transposable element Himar1 together with its transposase for random mutagenesis in Methanosarcina (Zhang et al. 2000) and, later, in Methanococcus (Sattler et al. 2013). Thus, any progress made will likely be useful for all other model systems.

Although it might not be possible to use genetically modified methanogens in the established methanogenic processes like biogasproduction or wastewater treatment, new genetic tools are necessary to guarantee the progress in methanogenic research. It will get clear in the next sections that modified methanogens can be used for bioproduction.

Applications of methanogens

Methanogenic archaea are a very diverse group and some strains can grow under extreme conditions, like extremely high or low temperatures, high osmolarities or pH values. Therefore, the development and optimization of industrially applicable processes making use of methanogens is desirable. This is not only true in terms of methane production as a technical relevant fuel (Ravichandran et al. 2015), but also for other products and applications.

Hydrogen production

It has been observed that several methanogenic strains can also produce hydrogen (Valentine et al. 2000; Goyal et al. 2016). This can happen if the amount of available hydrogen is limited (sub-nanomolar), so that the methanogens seem to start metabolic hydrogen production instead of hydrogen consumption; it has turned out that not methane, but formate and possibly other metabolites can be the source of H2; this cannot be seen as reverse methanogenesis (Valentine et al. 2000; Lupa et al. 2008). The hydrogen production observed by Valentine et al. reached 0.25 μmol/mg cell dry mass for Methanothermobacter marburgensis, 0.23 μmol/mg cell dry mass for Methanosaeta thermophila strain CALS-1 and 0.21 μmol/mg cell dry mass for M. barkeri strain 227 (Valentine et al. 2000). Several strains of M. maripaludis produced 1.4 μmol/mg of hydrogen per milligram of cell dry mass, out of formate (Lupa et al. 2008). This application is still restricted to the lab scale (Valentine et al. 2000) and to create a reasonable process, genetic engineering would have to be done to increase the hydrogen yield (Goyal et al. 2016). It is assumed that the hydrogenases present in methanogens are the enzymes catalyzing the hydrogen production (Valentine et al. 2000). A possible way to increase the hydrogen yield could therefore be the detection of the relevant hydrogenase and afterwards overexpressing it.

Biotechnological production by genetically modified methanogens

During recent years, genetic tools for methanogens have been improved, opening a new field of research on these important microorganisms. As a first step, the product spectra of methanogens could be increased. For example, it has been possible to modify M. maripaludis to produce geraniol instead of methane from CO2 + H2 or from formate (Lyu et al. 2016). Apart from allowing different products, it has also been possible to broaden the substrate range. As an example, the introduction of a bacterial esterase allowed M. acetivorans to grow on methyl-esters (like methyl acetate and methyl propionate, Lessner et al. 2010). In wild type methanogens, “trace methane oxidation” (i.e., “reverse methanogensis”) has been reported to occur during net methane production (Timmers et al. 2017). It has been possible to use this effect for acetate production: Heterologous expression in M. acetivorans of genes encoding methyl-CoM reductase from anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME-1) resulted in a strain that converted methane to acetate three times faster than the parental strain (Soo et al. 2016). Also, additional expression of the gene encoding 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (Hbd) from Clostridium acetobutylicum resulted in formation of l-lactate (0.59 g/g methane) from methane with acetate as intermediate, possibly by Hbd exhibiting lactate dehydrogenase activity in the heterologous host (McAnulty et al. 2017). Thus, the principal possibility might exist to engineer M. acetivorans for industrial production. However, as both conversion rates and product yields were low and for neither case the conversion stoichiometries reported, the applicability of such a system remains in question. The same holds true for the production of other high value products like amino acids or vitamins with methanogens, and due to their slow growth, a technical application is not yet developed (Schiraldi et al. 2002). But since there is continuous progress in the development of genetic tools for methanogens, as described above, it is thinkable that new processes with heterologeous methanogens will emerge during the next years.

Methane from oil and coal beds

Nearly two-thirds of the fossil oil remains within the oil fields if using conventional production methods (Gieg et al. 2008). It was observed that the residual oil can be converted to natural gas by a methanogenic consortium, which was added to the oil field (Gieg et al. 2008). The consortium used was gained from subsurface sediments and could be enriched with crude oil. Methanosaeta spec. was the dominant archaeon in the enrichment, which also contained syntrophic sulfate-reducing bacteria, Clostridiales, Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi. The consortium was added to samples of petroliferous cores from different oilfields, with residual oil saturation of the sandstone grains of approximately 30–40%. Methane could be produced with yields of up to 3.14 mmol/g crude oil (Gieg et al. 2008). Apart from oil fields, also oil sands tailing ponds or other oil–water emulsions could be treated that way (Voordouw 2011). But since costs for natural gas remain relatively low, whilst those for crude oil are significantly higher, this approach remains experimental due to lack of benefit (Voordouw 2011). A natural source of methane is coal bed methane. It has been discovered that about 40% of this methane are produced by microbial consortia containing methanogens (e.g. Methanosarcinales); the substrates for this production are methoxylated aromatic compounds within the coal beds (Mayumi et al. 2016). It was recently discovered that pure cultures of Methermicoccus shengliensis can produce up to 10.8 μM/(g coal) methane (Mayumi et al. 2016). Coal bed methane is already industrially used; it might be possible to use M. shengliensis for methane production from other sedimentary organic material (Mayumi et al. 2016).

Biogas production from organic matter

The main technical application of methanogens is the production of biogas by digestion of organic substrates. It is estimated that up to 25% of the bioenergy used in Europe could be produced using the biogas process until 2020 (Holm-Nielsen et al. 2009). Digestion of organic matter can be seen as a four-stage process. During the first step (hydrolysis), complex organic matter (proteins, polysaccharides, lipids) is hydrolyzed by exo-enzymes to oligo- and monomers (amino acids, sugars, long chain fatty acids), which can be taken up by microorganisms (Vavilin et al. 2008). The second step, fermentation or acidogenesis, leads to an oxidation of the compounds formed during hydrolysis to typical fermentation products like butyrate, propionate, acetate, formate, ethanol, H2 and CO2. Acetogenesis represent the third step, where the fermentation products are oxidized, mostly to acetate and CO2 with the concomitant formation of H2 (Batstone et al. 2002). However, this process is only sufficiently exergonic for the organisms if the H2 partial pressure is kept very low (McInerney et al. 2008). This requires the fourth step, methanogenesis, where acetate (and methylated compounds) and CO2 and H2 is converted to methane by the methanogens. This implicates that a syntrophic consortium of microorganisms is always needed, whereas the exact composition of this consortium can not only change over time, but also vary between different reactors (Solli et al. 2014). Depending on the microbial community and the type of methanogens within, this process can be carried out in psychrophilic, mesophilic or thermophilic temperature range (Vanegas and Bartlett 2013). For stable biogas production, hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis and methanogenesis have to run within the digester in balanced reaction rates to prevent the overacidification of the reactor by surplus protons. However, the microorganisms responsible for these different steps often have different optimal growth conditions, so it is crucial that conditions are maintained, which favor all steps (Niu et al. 2015). Therefore, careful control of process parameters like temperature (Vanegas and Bartlett 2013), hydraulic retention time (Rincón et al. 2008), pH (Lay et al. 1997) and ammonia concentration (Karakashev et al. 2005) are necessary. Apart from that, the biogas yield and the process operation and conditions strongly depend on the type of substrate used (Niu et al. 2015). It was for example observed that the methanogenic consortium, which is strongly depending on the substrate type, is usually dominated by Methanosaetaceae in digesters with sludge as substrate, while solid waste digesters operated with manure explained in the following section usually host a majority of Methanosarcinaceae (Karakashev et al. 2005). In both cases, methanogens that can metabolize acetate (see also “Substrates and metabolism of methanogens” section) are preferred in biogas systems, compared to those feeding on hydrogen and CO2. Apart from the substrate type itself, a differentiation is made between wet and dry fermentation, whereby the more common wet fermentation includes up to 10% of solids in the substrate, and the dry fermentation between 15 and 35% (Stolze et al. 2015).

Treatment of sewage water

The treatment of sewage water by anaerobic digestion does not only lead to biogas production but also to clean water. Using a methanogenic process to convert the organic matter within wastewater to biogas reduces the amount of sludge to be disposed, lowers its pathogenic potential and usually needs less additional energy than aerobic processes, since biogas as energy fuel is produced and no energy intense aeration is necessary (Martin et al. 2011). Apart from that, the greenhouse gas emission of the anerobic process is lower when treating high strength waste waters, although no greenhouse gas savings could be detected for low strength sewage water (Cakir and Stenstrom 2005).

A commonly used system for the anaerobic treatment of wastewater is the upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor; wastewater enters the reactor from the bottom and flows to an outlet in the upper part of the reactor. Sludge particles out of the waste water agglomerate and form a sludge blanket, which has to be passed by the incoming wastewater. In this zone, the methanogenic consortium digests organic material and produces biogas, which leaves the reactor at its top. Since the solubility of methane in water is low compared to that of CO2, the holdup of methane within the water is negligible (Sander 2015). The contact between organic material and microorganisms is sufficient for efficient methane production due to the sludge blanket, thus allowing higher loading rates than in other reactor types. The system only requires a low energy input, but needs a long start-up phase of several months, until the sludge blanket has fully established (Rajeshwari et al. 2000). To overcome long start up phases, continuously stirred tank reactors can be used, but here, organic loading rates are about tenfold lower than in the UASB reactor (Rajeshwari et al. 2000). It is important to consider the type of sewage water (e.g. from breweries, paper mills, oil mills, dairy production or other) when estimating the biogas yield of digestion. Different organic loads or different substrate composition lead not only to fluctuating amounts of biogas, but also to changes of the biogas composition (reviewed by Tabatabaei et al. 2010). Instead of treating sewage water itself via anaerobic digestion, it is also possible to purify the water by aerobic processes and anaerobically digest the remaining sewage sludge (Van Lier et al. 2008). Usually, a pretreatment of the sludge can increase the biogas yield. This can for example, but not only, be an alkaline pretreatment, ozonation, ultrasonic pretreatment or electric pulses to increase the biodegradability of the sludge (Wonglertarak and Wichitsathian 2014; Bougrier et al. 2007; Rittmann et al. 2008; for a recent review see: Neumann et al. 2016).

Treatment of solids

The largest amount of biodegradable waste for biogas production can be obtained from the agricultural sector. This includes animal manure and slurry from the production of pig, poultry, fish and cattle (Holm-Nielsen et al. 2009). The treatment of agricultural wastes like animal manure with methanogenic consortia is not only beneficial in terms of the biogas produced. It also reduces odors and pathogens and is therefore increasing the fertilizer qualities of the manure (Sahlström 2003). The process of biogas formation does not necessarily have to be coupled to waste treatment. Biogas plants can also be operated with energy crops cultured for the biogas production, like sugar beet or maize silage (Demirel and Scherer 2008; Lebuhn et al. 2008). Another possibility is the anaerobic digestion of microalgae, which lowers the necessary cultivation area (Mussgnug et al. 2010). Especially if energy crops without addition of manure are digested, it can be necessary to add micronutrients to ensure optimum growth conditions (Choong et al. 2016). It is also important to consider that lignocellulosic materials are not fully convertible without pretreatment, which leads to lower methane yields (Zheng et al. 2014). Table 2 shows production yields for different solid substrates.

A crucial aspect of the biogas process is the design of the anaerobic digester (Nizami and Murphy 2010). There are several digester types for the anaerobic digestion of wastewater. For the digestion of solids, biogas plants are usually designed as continuously stirred tank reactors (CSTRs). Even though this might be the easiest and cheapest way of biogas production, it turned out that the efficiency can be increased by using a serial system. Here, two CSTRs are used; biogas yield was increased by a longer overall retention time (Boe and Angelidaki 2009; Kaparaju et al. 2009). Instead of CSTRs, plug-flow systems have been invented by different companies to perform continuous processes (Fig. 3); in a serial digestion, they would usually be taken for the first stage (Weiland 2010). Another possibility is the use of a batch process, especially for substrates with low water contents, for example in a garage type fermenter (Li et al. 2011; Nizami and Murphy 2010).

Plug flow digesters for biogas production. a “Kompogas” reactor. Horizontal plug flow reactor. Additional mixing by axial mixer. Increased process condition stability by partial effluent recycling. Gas outlet on top of the outlet side. 23–28% total solids. b Valorga reactor. Substrate entry at the bottom; plug flow over a vertical barrier to the outlet. Additional mixing by biogas injection at the bottom. 25–35% total solid content. c Dranco reactor. Substrate entry wit partial effluent recycling at the bottom, upward flow through substrate pipes. Downward plug flow to outlet. 30–40% total solids (Li et al. 2011; Nizami and Murphy 2010)

Micro biogas systems

An interesting application of the biogas process is the use of micro biogas plants in developing countries. These plants of up to 10 m3 can be operated using domestic organic waste or feces, while the produced gas can be used directly for heating and cooking. There are also attempts to convert the biogas out of those digesters with volumes of up to 10 m3 to electricity, which might be valuable in rural areas (Plöchl and Heiermann 2006). These reactors are particularly popular in China and India and programs to equip households with biogas energy are supported by the government (Bond and Templeton 2011). Domestic biogas plants are especially beneficial in warm regions (e.g. Africa around the equator, South-East Asia) with sufficient water available. In general, 3 types of digesters are used, which are the fixed dome, the floating cover digester, which was further developed to the ARTI biogas system, and the plug flow (or tube) system (Fig. 4).

Micro biogas systems. a Arti biogas (India). Material two plastic water tanks (working volume of 1 m3). Substrate mainly kitchen waste. Disadvantage of gas losses of up to 20% (Voegeli et al. 2009). b Floating cover (India). Material bricks and metal cover. Top rises when gas is produced. Substrate mainly pig and cow manure (Bond and Templeton 2011). c Fixed dome (China). Material bricks and clay. Substrate mainly pig and cow manure (Plöchl and Heiermann 2006). d Plug flow. Material affordable plastic foils (Bond and Templeton 2011)

Although micro biogas systems might not solve the energy problems in developing countries, and the investment costs may not be covered without governmental subsidy, some positive impacts of this technology can be observed. The deforestation in rural areas decreases since wood is not needed for heating, at the same time risks caused by open fire in closed buildings are minimized by the use of a biogas driven stove. The amount of pathogens in the substrate (waste and feces) is decreased, so that it can be reused as fertilizer (Bond and Templeton 2011). Therefore, microbiogas systems are an important contribution to the development of third world countries and a use of the biogasprocess not standing in conflict to food-production, since organic waste is the main substrate.

Biogas composition and process optimizations

The composition of biogas does not only include methane, but also up to 40% CO2, water, hydrogen sulfide and other trace gases. Biogas is usually flammable due to the high yield of methane (40–75%), but for the use in engines or for injection into the natural gas grid it has to be purified and upgraded in methane content. This leads to higher calorific values of the biogas and avoids the presence of corrosive gases like hydrogen sulfide, which could cause damages to engines and pipes if remaining in the biogas (Ryckebosch et al. 2011). There are several upgrading techniques, which take place after digestion (extensively reviewed by Bauer et al. 2013). Process optimization can influence the biogas composition already during the process, lowering the costs of after-process purification. Numerous investigations on improvement of the biogas process have been undertaken, either to increase the overall amount of biogas, or to increase the methane content of the biogas.

It has turned out that careful pretreatment of the organic substrates leads to higher percentages of methane in the biogas. Several pretreatment methods such as chopping, alkali treatment and thermal treatment are reviewed in Andriani et al. (2014). From a biotechnological point of view, biological pretreatment of substrate is especially interesting. Biological pretreatment can increase the biogas production; this method was described by Zhong et al. (2011) which led to a 33% increase of biogas production (Zhong et al. 2011). The substrates were exposed to a microbial agent including yeasts, celluleutic bacteria and lactic acid bacteria, which degraded the substrate before the actual start of the anaerobic digestion. A reduction in lignin, cellulose and hemicelluloses content could be observed after 15 days of pretreatment. The following anaerobic digestion showed an increase of biogas yield and methane content (Zhong et al. 2011). Apart from the pretreatment of the single substrates, a mixture of different substrates (co-digestion) or a backmixing of digester effluent can lead to a better performance of the system (Weiland 2010; Sosnowski et al. 2003). Co-digestions can be carried out with mixtures of manure and energy plants or sewage slug and solid wastes and increase the methane production because of stabilizing the C:N ratio within the digester (Ward et al. 2008; Sosnowski et al. 2003). Another optimization method is addition of inorganic particles to the fermentation medium. Addition of nanoparticles of zero-valent iron could enhance the methane production by 28% (Carpenter et al. 2015). An increase in biogas formation could also be observed with magnetic iron oxide particles (Abdelsalam et al. 2017). Other particles include charcoal, silica and mineral salts were investigated (reviewed by Yadvika et al. 2004). The improvement in biogas yield could be due to aggregation of bacteria and methanogens around the particles, leading to a lower washout and higher culture densities; it is also possible that metal particles release electrons to the surrounding medium, which can be used for methane formation, but the exact mechanism remains unclear (Yadvika et al. 2004; Carpenter et al. 2015).

One promising method for biological biogas upgrading in methane content is the conversion of the residual CO2 to additional methane using hydrogenothrophic methanogens, which are capable of producing methane solely out of CO2 and H2 (Bassani et al. 2015). H2 can either be injected into the anaerobic digester (Luo et al. 2012), or H2 and biogas can be mixed in a second reactor containing methanogens (Bassani et al. 2015; Luo and Angelidaki 2012) (Fig. 5). If introducing hydrogen to the anaerobic digester, there may be a shift within the methanogenic community: acetoclastic methanogens decrease, while hydrogenotrophic methanogens (especially Methanoculleus) are enriched; also, hydrolyzing and acidifying bacteria decrease, while synthrophic bacteria producing acetate increase (see also “Substrates and metabolism of methanogens” section; Bassani et al. 2015). Technical concepts for the integration of H2 into existing biogas plants and effective new means of process control are necessary to make this process commercially attractive. Therefore, experiments have to be carried out under industrial conditions, i.e. under fluctuating substrate compositions, in reactors with zones of different substrate concentrations, changing microbial consortium and different pressure zones according to a larger reactor height; these conditions will usually not appear in lab scale, unless they are particularly tested.

H2 is usually produced by water electrolysis, a process in which electricity is used to split water and generate oxygen and hydrogen. To couple water electrolysis to anaerobic methanogenesis and provide a constant level of H2 within the digester, methanogenic bioelectrochemical systems were invented.

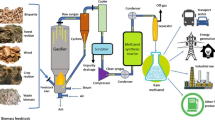

Methanogenic bioelectrochemical systems

The successful increase of methane production by iron addition leads to the conclusion that methanogens may use inorganic surfaces to boost their metabolism by exchange of electrons with the inorganic material (Carpenter et al. 2015). On the other hand, hydrogen addition could also increase the methane output of a biogas plant. A methanogenic bioelectrochemical system (BES) combines these two improvements for increased methane production (Koch et al. 2015). Here, electrodes are introduced into the reaction medium and an external potential is applied. Methanogens can now either interact directly with the electrode surface to gain electrons (Cheng et al. 2009), and/or hydrogen can be produced at the cathode, which can then be consumed by the methanogens to produce methane (Geppert et al. 2016). The whole process belongs to the field of microbial electrosynthesis (MES), which includes processes that convert a substrate into a desired organic product by using microorganisms and electrical current (Schröder et al. 2015; Lovley 2012; Holtmann et al. 2014). The advantage of a BES system compared to the external production of hydrogen is that short time storage and gassing in of the hardly soluble hydrogen can be avoided (Butler and Lovley 2016).

Notably, the electrode material and size, the membrane material and size and the applied voltage strongly influences the performance of electromethanogenesis, (see Babanova et al. 2017; Krieg et al. 2014; Ribot-Llobet et al. 2013; Siegert et al. 2014 for reviews), but “optimal” conditions for microbial growth and production have not yet been found (Blasco-Gómez et al. 2017). Investigations of this (relatively new) technology have been mostly carried out in lab scale so far, with very few pilot scale approaches (for hydrogen production with methane as side product, see Cusick et al. 2011). Yet, no scale up concept or even well characterized reactor concept exists for electromethanogenesis, whereas various types of bioelectrochemical reactors have been designed (reviewed in Geppert et al. 2016; Krieg et al. 2014; Kadier et al. 2016). Two general modes of integrating electrochemistry into the methanogenic process can be distinguished: first, the electrodes can be integrated into the anaerobic digestion of sewage water or other organic wastes, and secondly, the methanogenic BES can be placed into a second reactor as a stand-alone-process, fed with CO2, but without additional organic substrates (Fig. 6).

Integration of electrodes into waste and wastewater treatment

To enhance the production of biogas and increase biogas purity, electrodes can be inserted into the anaerobic digester for in situ biogas upgrading. CO2, which is produced during the digestion of organic matter, can be converted to methane at the electrodes without an additional reactor (Bo et al. 2014). Therefore, the biogas production can be performed during wastewater treatment (Guo et al. 2017) or sewage sludge treatment (Guo et al. 2013) as well as in a mere biogas producing process (Gajaraj et al. 2017). The methane content within the biogas reached up to 98.1% during the digestion of activated sludge and acetate (Bo et al. 2014). It has been shown that the integration of electrodes alters the microbial consortium within the plant, while it is also possible to use adapted consortia, e.g. for psychrophilic temperature ranges (Koch et al. 2015; Bo et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2016). To achieve a reasonable process, ways of electrode integration into existing treatment plants need to be established.

Bioelectrochemical systems fed with CO2

Methanogenic microbial electrosynthesis can also be carried out in a second reactor, which is equipped with electrodes and fed with CO2 or a gas containing CO2. Gas streams rich in CO2 can be biogas, syngas, or industrial flue gas. The CO2 contained is often considered a waste component of these gas streams, and since it is also a greenhouse gas, the conversion of CO2 to more useful chemicals is desirable (Dürre and Eikmanns 2015; Geppert et al. 2016). The conversion of CO2 by methanogens takes place at the cathode of the system. Since anodic processes like oxygen generation or acid production could inhibit the methanogens, the process can be carried out in a two-chamber system, were anode and cathode chamber are separated by a proton-exchange membrane, which allows the transfer of protons from anode to cathode chamber; this is necessary to allow electrical current in the system and maintain the pH within the cathode chamber (Dykstra and Pavlostathis 2017; Cheng et al. 2009). In this system, it is possible to use a pure methanogenic culture (Beese-Vasbender et al. 2015) or an enriched methanogenic consortium (Dykstra and Pavlostathis 2017) at the cathode, while the anode chamber can be abiotic (water electrolysis) or biotic (degradation of organic matter) (Dykstra and Pavlostathis 2017).

As mentioned, the bioelectrochemical methanogensis is currently still a lab-scale application. To gain a economical technical process, concepts for process characterization and control, reactor balancing, and scale up of reactors have to be developed. To create further progress in this field and also in bioelectrochemical applications, genetic tools might be necessary to create methanogens with higher electron uptake rates, e.g. via the integration of (more) cytochromes into the membrane or the heterologeous secretion of electron shuttles.

Conclusions

Methanogens are interesting organisms, both from a biological, as well as for a technological, point of view. Research of the last years made it clear that this unique group of microbes is far from being fully understood. During the last years, several reviews on biological aspects of methanogens (Borrel et al. 2016; Goyal et al. 2016), on natural methanogenesis (e.g. Park and Liang 2016; Bao et al. 2016) or on single technical applications, eventually in combination with the very specific biology within the process (Biogas: Wang et al. 2017; Braguglia et al. 2017; Koo et al. 2017; Biogas upgrading and optimization: Neumann et al. 2016; Choong et al. 2016; Romero-Güiza et al. 2016; Bioelectromethanation: Blasco-Gómez et al. 2017; Geppert et al. 2016) have been published. All these review articles are rather specialized to one single aspect of methanogens. This review combines all these aspects, including a review of recently developed tools, to give an overview over the whole field of methanogenic research. Therefore, it makes it possible to understand challenges in industrial applications by giving the biological basics and helps to imagine applications for results from basic research in industry. Industry mainly focused on the production of biogas with methanogens, but other applications, especially when considering electroactivity of methanogens, seem feasible. Newly developed genetic tools for methanogens are useful to design a wider product spectrum, which raises the technical relevance of methanogens. However, most processes possible with methanogens are still not economically feasible, since their strict requirement for anaerobic conditions raises the investment costs and their slow growth leads to long process times. It would be desirable to have further comparable knowledge of the efficiency of different methanogenic strains in terms of space time yield and conversion rates under industrially relevant conditions, for example by performing pure culture studies with fluctuating substrate composition, fluctuating pH and under different substrate concentrations. A major problem here remains the comparability of published data about methanogenic performance in biogas plants as well as in electrochemical systems, since studies have been carried out under various conditions. For some applications, especially microbial electrosynthesis, more research of the methanogenic community and comparisons between pure and mixed cultures have to be done to increase methane yields. Still, process optimization, like the use of CO2-rich waste gas streams as substrates and intelligent process integration will favor methanogenic processes beyond waste treatment in the future. Scale-up of reactors, e.g., for electromethanogenesis or biogas-upgrading, are a major task for process engineers, while genetic engineering may pave the way to produce higher value products from waste CO2 employing methanogens.

Abbreviations

- BES:

-

bioelectrochemical system

- CoA:

-

coenzyme A

- CoB:

-

coenzyme B

- CoM:

-

coenzyme M

- CODH:

-

CO dehydrogenase

- CSTRs:

-

continuously stirred tank reactors

- DET:

-

direct electron transfer

- DIET:

-

direct interspecies electron transfer

- Ech:

-

energy converting hydrogenase

- Fd:

-

ferredoxin

- Fdox :

-

oxidized ferredoxin

- Fdred :

-

reduced ferredoxin

- Fdh:

-

formate dehydrogenase

- Fpo:

-

F420H2 dehydrogenase

- Hbd:

-

3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase

- Hdr:

-

heterodisulfide reductase

- H4MTP:

-

tetrahydromethanopterin

- H4SPT:

-

tetrahydrosarcinapterin

- IET:

-

indirect electron transfer

- MES:

-

microbial electrosynthesis

- MET:

-

mediated electron transfer

- MFR:

-

methanofuran

- MPh:

-

methanophenazine

- MPhH2 :

-

reduced methanophenazine

- Mtr:

-

methyl-H4MPT:coenzyme M methyltransferase

- Mvh-Hdr:

-

(methyl viologen-reducing) hydrogenase and heterodisulfide reductase

- PHB:

-

polyhydroxybutyric acid

- SHE:

-

standard hydrogen electrode

- SLP:

-

substrate level phosphorylation

- UASB:

-

upflow anaerobic sludge blanket

- Vho:

-

(F420 non-reducing) hydrogenase

References

Abdelsalam E, Samer M, Attia YA, Abdel-Hadi MA, Hassan HE, Badr Y (2017) Influence of zero valent iron nanoparticles and magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on biogas and methane production from anaerobic digestion of manure. Energy 120:842–853

Amon T, Amon B, Kryvoruchko V, Bodiroza V, Pötsch E, Zollitsch W (2006) Optimising methane yield from anaerobic digestion of manure: effects of dairy systems and of glycerine supplementation. Int Congr Ser 1293:217–220

Andriani D, Wresta A, Atmaja TD, Saepudin A (2014) A review on optimization production and upgrading biogas through CO2 removal using various techniques. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 172:1909–1928

Argyle JL, Tumbula DL, Leigh JA (1996) Neomycin resistance as a selectable marker in Methanococcus maripaludis. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:4233–4237

Asakawa S, Akagawa-Matsushita M, Morii H, Koga Y, Hayano K (1995) Characterization of Methanosarcina mazeii TMA isolated from a paddy field soil. Curr Microbiol 31:34–38

Babanova S, Carpenter K, Phadke S, Suzuki S, Ishii S, Phan T, Grossi-Soyster E, Flynn M, Hogan J, Bretschger O (2017) The effect of membrane type on the performance of microbial electrosynthesis cells for methane production. J Electrochem Soc 164:H3015–H3023

Balch WE, Fox GE, Magrum LJ, Woese CR, Wolfe RS (1979) Methanogens: reevaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiol Rev 43:260–296

Bao Y, Huang H, He D, Ju Y, Qi Y (2016) Microbial enhancing coal-bed methane generation potential, constraints and mechanism - a mini-review. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 35:68–78

Bapteste E, Brochier C, Boucher Y (2005) Higher-level classification of the Archaea: evolution of methanogenesis and methanogens. Archaea 1:353–363

Bär K, Mörs F, Götz M, Graf F (2015) Vergleich der biologischen und katalytischen Methanisierung für den Einsatz bei PtG-Konzepten. gwf-Gas 7:1–8

Bassani I, Kougias PG, Treu L, Angelidaki I (2015) Biogas upgrading via hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in two-stage continuous stirred tank reactors at mesophilic and thermophilic conditions. Environ Sci Technol 49:12585–12593

Batlle-Vilanova P, Puig S, Gonzalez-Olmos R, Vilajeliu-Pons A, Balaguer MD, Colprim J (2015) Deciphering the electron transfer mechanisms for biogas upgrading to biomethane within a mixed culture biocathode. RSC Adv 5:52243–52251

Batstone DJ, Keller J, Angelidaki I, Kalyuzhnyi SV, Pavlostathis SG, Rozzi A, Sanders WT, Siegrist H, Vavilin VA (2002) The IWA anaerobic digestion model no 1 (ADM1). Water Sci Technol 45:65–73

Bauer F, Persson T, Hulteberg C, Tamm D (2013) Biogas upgrading - technology overview, comparison and perspectives for the future. Biofuels, Bioprod Biorefin 7:499–511

Becher B, Müller V, Gottschalk G (1992) The methyl-tetrahydromethanopterin: coenzyme M methyltransferase of Methanosarcina strain Gö1 is a primary sodium pump. FEMS Microbiol Lett 91:239–243

Beese-Vasbender PF, Grote J-P, Garrelfs J, Stratmann M, Mayrhofer KJJ (2015) Selective microbial electrosynthesis of methane by a pure culture of a marine lithoautotrophic archaeon. Bioelectrochemistry 102:50–55

Belay N, Johnson R, Rajagopal BS, Conway de Macario E, Daniels L (1988) Methanogenic bacteria from human dental plaque. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:600–603

Beneke S, Bestgen H, Klein A (1995) Use of the Escherichia coli uidA gene as a reporter in Methanococcus voltae for the analysis of the regulatory function of the intergenic region between the operons encoding selenium-free hydrogenases. Mol Gen Genet 248:225–228

Blasco-Gómez R, Batlle-Vilanova P, Villano M, Balaguer M, Colprim J, Puig S (2017) On the edge of research and technological application: a critical review of electromethanogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 18:874

Bo T, Zhu X, Zhang L, Tao Y, He X, Li D, Yan Z (2014) A new upgraded biogas production process: coupling microbial electrolysis cell and anaerobic digestion in single-chamber, barrel-shape stainless steel reactor. Electrochem Commun 45:67–70

Boccazzi P, Zhang JK, Metcalf WW (2000) Generation of dominant selectable markers for resistance to pseudomonic acid by cloning and mutagenesis of the ileS gene from the archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri fusaro. J Bacteriol 182:2611–2618

Boe K, Angelidaki I (2009) Serial CSTR digester configuration for improving biogas production from manure. Water Res 43:166–172

Bond T, Templeton MR (2011) History and future of domestic biogas plants in the developing world. Energy Sustain Dev 15:347–354

Borrel G, Adam PS, Gribaldo S (2016) Methanogenesis and the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway: an ancient, versatile, and fragile association. Genome Biol Evol 8:1706–1711

Bougrier C, Battimelli A, Delgenes JP, Carrere H (2007) Combined ozone pretreatment and anaerobic digestion for the reduction of biological sludge production in wastewater treatment. Ozone Sci Eng 29:201–206

Braguglia CM, Gallipoli A, Gianico A, Pagliaccia P (2017) Anaerobic bioconversion of food waste into energy: a critical review. Bioresour Technol. 248(Pt A):37–56

Bräuer SL, Cadillo-Quiroz H, Yashiro E, Yavitt JB, Zinder SH (2006) Isolation of a novel acidiphilic methanogen from an acidic peat bog. Nature 442:192–194

Bräuer SL, Cadillo-Quiroz H, Ward RJ, Yavitt JB, Zinder SH (2011) Methanoregula boonei gen. nov., sp. nov., an acidiphilic methanogen isolated from an acidic peat bog. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:45–52

Bryant MP, Boone DR (1987) Emended description of strain MST (DSM 800T), the type strain of Methanosarcina barkeri. Int J Syst Bacteriol 37:169–170

Buckel W, Thauer RK (2013) Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na+ translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1827:94–113

Burke SA, Krzycki JA (1997) Reconstitution of monomethylamine: coenzyme M methyl transfer with a corrinoid protein and two methyltransferases purified from Methanosarcina barkeri. J Biol Chem 272:16570–16577

Butler CS, Lovley DR (2016) How to sustainably feed a microbe: strategies for biological production of carbon-based commodities with renewable electricity. Front Microbiol 7:1879

Cakir FY, Stenstrom MK (2005) Greenhouse gas production: a comparison between aerobic and anaerobic wastewater treatment technology. Water Res 39:4197–4203

Carpenter AW, Laughton SN, Wiesner MR (2015) Enhanced biogas production from nanoscale zero valent iron-amended anaerobic bioreactors. Environ Eng Sci 32:647–655

Cheng S, Xing D, Call DF, Logan BE (2009) Direct biological conversion of electrical current into methane by electromethanogenesis. Environ Sci Technol 43:3953–3958

Choi O, Sang B-I (2016) Extracellular electron transfer from cathode to microbes: application for biofuel production. Biotechnol Biofuels 9:11

Choong YY, Norli I, Abdullah AZ, Yhaya MF (2016) Impacts of trace element supplementation on the performance of anaerobic digestion process: a critical review. Bioresour Technol 209:369–379

Cohen-Kupiec R, Blank C, Leigh JA (1997) Transcriptional regulation in Archaea: in vivo demonstration of a repressor binding site in a methanogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:1316–1320

Cusick RD, Bryan B, Parker DS, Merrill MD, Mehanna M, Kiely PD, Liu G, Logan BE (2011) Performance of a pilot-scale continuous flow microbial electrolysis cell fed winery wastewater. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 89:2053–2063

Daniels L, Fuchs G, Thauer RK, Zeikus JG (1977) Carbon monoxide oxidation by methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 132:118–126

Demirel B, Scherer P (2008) Production of methane from sugar beet silage without manure addition by a single-stage anaerobic digestion process. Biomass Bioenergy 32:203–209

Demolli S, Geist MM, Weigand JE, Matschiavelli N, Suess B, Rother M (2014) Development of β-lactamase as a tool for monitoring conditional gene expression by a tetracycline-riboswitch in Methanosarcina acetivorans. Archaea 2014:1–10

Deutzmann JS, Spormann AM (2017) Enhanced microbial electrosynthesis by using defined co-cultures. ISME J 11:704–714

Deutzmann JS, Sahin M, Spormann AM (2015) Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis. mBio 6(2):e00496–15

Doudna JA, Charpentier E (2014) The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346:1258096

Dridi B, Henry M, El Khéchine A, Raoult D, Drancourt M (2009) High prevalence of Methanobrevibacter smithii and Methanosphaera stadtmanae detected in the human gut using an improved DNA detection protocol. PLoS ONE 4:e7063

Dridi B, Fardeau M-L, Ollivier B, Raoult D, Drancourt M (2012) Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 62:1902–1907

Dürre P, Eikmanns BJ (2015) C1-carbon sources for chemical and fuel production by microbial gas fermentation. Curr Opin Biotechnol 35:63–72

Dykstra CM, Pavlostathis SG (2017) Evaluation of gas and carbon transport in a methanogenic bioelectrochemical system (BES). Biotechnol Bioeng 114:961–969

Evans PN, Parks DH, Chadwick GL, Robbins SJ, Orphan VJ, Golding SD, Tyson GW (2015) Methane metabolism in the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota revealed by genome-centric metagenomics. Science 350:434–438

Fantozzi F, Buratti C (2009) Biogas production from different substrates in an experimental Continuously Stirred Tank Reactor anaerobic digester. Bioresour Technol 100:5783–5789

Feng Y, Zhang Y, Chen S, Quan X (2015) Enhanced production of methane from waste activated sludge by the combination of high-solid anaerobic digestion and microbial electrolysis cell with iron–graphite electrode. Chem Eng J 259:787–794

Ferrari A, Brusa T, Rutili A, Canzi E, Biavati B (1994) Isolation and characterization of Methanobrevibacter oralis sp. nov. Curr Microbiol 29:7–12

Frimmer U, Widdel F (1989) Oxidation of ethanol by methanogenic bacteria. Arch Microbiol 152:479–483

Fu Q, Kuramochi Y, Fukushima N, Maeda H, Sato K, Kobayashi H (2015) Bioelectrochemical analyses of the development of a thermophilic biocathode catalyzing electromethanogenesis. Environ Sci Technol 49:1225–1232

Gajaraj S, Huang Y, Zheng P, Hu Z (2017) Methane production improvement and associated methanogenic assemblages in bioelectrochemically assisted anaerobic digestion. Biochem Eng J 117:105–112

Garcia J-L, Patel BK, Ollivier B (2000) Taxonomic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of methanogenic Archaea. Anaerobe 6:205–226

Gardner WL, Whitman WB (1999) Expression vectors for Methanococcus maripaludis: overexpression of acetohydroxyacid synthase and beta-galactosidase. Genetics 152:1439–1447

Ge X, Yang L, Sheets JP, Yu Z, Li Y (2014) Biological conversion of methane to liquid fuels: status and opportunities. Biotechnol Adv 32:1460–1475

Geppert F, Liu D, van Eerten-Jansen M, Weidner E, Buisman C, ter Heijne A (2016) Bioelectrochemical power-to-gas: state of the art and future perspectives. Trends Biotechnol 34:879–894

Gernhardt P, Possot O, Foglino M, Sibold L, Klein A (1990) Construction of an integration vector for use in the archaebacterium Methanococcus voltae and expression of a eubacterial resistance gene. Mol Gen Genet 221:273–279

Gieg LM, Duncan KE, Suflita JM (2008) Bioenergy production via microbial conversion of residual oil to natural gas. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3022–3029

Gorby YA, Yanina S, McLean JS, Rosso KM, Moyles D, Dohnalkova A, Beveridge TJ, Chang IS, Kim BH, Kim KS, Culley DE, Reed SB, Romine MF, Saffarini DA, Hill EA, Shi L, Elias DA, Kennedy DW, Pinchuk G, Watanabe K, Ishii S, Logan B, Nealson KH, Fredrickson JK (2006) Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:11358–11363

Gottschalk G, Thauer RK (2001) The Na(+)-translocating methyltransferase complex from methanogenic archaea. Biochim Biophys Acta 1505:28–36

Goyal N, Zhou Z, Karimi IA (2016) Metabolic processes of Methanococcus maripaludis and potential applications. Microb Cell Fact 15:107

Grüber G, Manimekalai MSS, Mayer F, Müller V (2014) ATP synthases from archaea: the beauty of a molecular motor. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1837:940–952

Guo X, Liu J, Xiao B (2013) Bioelectrochemical enhancement of hydrogen and methane production from the anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge in single-chamber membrane-free microbial electrolysis cells. Int J Hydrogen Energy 38:1342–1347

Guo Z, Thangavel S, Wang L, He Z, Cai W, Wang A, Liu W (2017) Efficient methane production from beer wastewater in a membraneless microbial electrolysis cell with a stacked cathode: the effect of the cathode/anode ratio on bioenergy recovery. Energy Fuels 31:615–620

Guss AM, Rother M, Zhang JK, Kulkarni G, Metcalf WW (2008) New methods for tightly regulated gene expression and highly efficient chromosomal integration of cloned genes for Methanosarcina species. Archaea 2:193–203

Hara M, Onaka Y, Kobayashi H, Fu Q, Kawaguchi H, Vilcaez J, Sato K (2013) Mechanism of electromethanogenic reduction of CO2 by a thermophilic methanogen. Energy Procedia 37:7021–7028

Harris JE, Pinn PA (1985) Bacitracin-resistant mutants of a mesophilic Methanobacterium species. Arch Microbiol 143:151–153