Abstract

We formulate a stochastic impulse control model for animal population management and a candidate of exact solutions to a Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality. This model has a qualitatively different functional form of the performance index from the existing monotone ones. So far, optimality and unique solvability of the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality has not been investigated, which are thus addressed in this paper. We present a candidate of exact solutions to the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality and prove its optimality and unique solvability within a certain class of solutions in a viscosity sense. We also present and examine a dynamical system-based numerical method for computing coefficients in the exact solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper focuses on mathematical analysis of an exact viscosity solution to Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality arising in an animal population management problem. Our problem, despite it is relatively simple, is important from mathematical, environmental and ecological engineering standpoints since many management problems can be described and/or analyzed with mathematical tools focused on in our paper. Our results are mathematical ones but providing a background of the problem is important for understanding it. Hence, we firstly describe the problem background in this section.

Management of animal population, such as fishery resources and their predators, is an important ecological problem. Such examples include aquaculture of Plecoglossus altivelis (P. altivelis, Ayu) in Japan [1], extermination of its predator bird Phalacrocorax carbo (P. carbo, Great cormorant) [2, 3], agricultural crops damage by a wild boar Sus scrofa in Europe [4], and feeding damage from many insects to soybean seeds [5]. Recently, fish-eating bird P. carbo population has been increasing worldwide, such as in Japan [6], Europe [7], North America [8], and Greenland [9]. The increase of the population causes several problems. In Japan, feeding damage from fish-eating birds, such as P. carbo, to inland fishery resources, has been increasing and is currently one of the most severe problems to be solved [6]. Cost-effective and ecologically-sound bird population management policy is required for effective reduction of the feeding damage.

Stochastic optimal control theory [10] has been applied to population and resource management problems [1, 11,12,13,14]. In reality, there are fixed costs besides proportional costs when some interventions are performed for management of animal population. Stochastic impulse control theory serves as an effective mathematical tool for dealing with this issue [14,15,16,17] and has been applied to many problems, such as finance and economics [18,19,20], and animal population management by the authors [21].

Finding an optimal control policy in the context of stochastic impulse control reduces to solving a Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality (HJBQVI), a degenerate elliptic or parabolic differential inequality. Many researchers have investigated mathematical properties of HJBQVIs. In Cadenillas [17], the performance index is quadratic monomial (convex). He proposed a candidate of the exact solution to the HJBQVI and proved a verification theorem and that the exact solution satisfies the HJBQVI. Existence and uniqueness of exact solutions has not been proved. In Ohnishi and Tsujimura [15] and Øksendal [21], the performance index is quadratic monomial (convex). They proposed a candidate of the exact solution to the HJBQVI and proved a verification theorem, existence and uniqueness of the exact solution, and that it satisfies the HJBQVI. Note that in Ohnishi and Tsujimura [15], the cost function is quadratic unlike those of Cadenillas [17], Øksendal [21], and this paper. In addition, viscosity solutions are appropriate weak solutions for degenerate elliptic and parabolic equations [22,23,24], and are appropriate solutions to HJBQVIs.

Recently, Yaegashi et al. [3] proposed an optimal control model for cost-effective and sustainable management of P. carbo and a candidate of its exact viscosity solution to a HJBQVI. This model has a different performance index from those in the above-mentioned literature. However, existence and uniqueness of the solution, and its optimality namely the verification, have not been discussed so far. If we could give an answer on the above-mentioned problems about the exact solution, the solution and the associated optimal policy can establish a firm position as a reasonable mathematical tool. This is the motivation of this paper.

The objectives of this paper are thus to formulate the stochastic impulse control model of an animal population management, to present a candidate of the exact solutions to a HJBQVI, and to prove its optimality and unique solvability within a certain class of solutions from a viscosity viewpoint. The novelty of this paper against the previous studies from Cadenillas [17], Ohnishi and Tsujimura [15], and Øksendal [21] is the point that our performance index is based on a concave polynomial as a sum of two monomials. Our performance index is therefore not based on monotone functions as in the above-mentioned models. We also propose and examine a numerical method to compute the coefficients of the exact solution.

The rest of this paper consists of 4 Sections and 3 Appendices. Section 2 introduces our model. Section 3 provides the exact solution. Section 4 concerns mathematical analysis of the exact solution. Section 5 presents and examines the numerical method. Section 6 concludes this paper. Appendix A contains the proofs of lemmas in Sects. 2 and 4. Appendix B contains the proofs of Theorems 4.2 and 4.3. Finally, Appendix C presents the proof of Theorem 5.1.

2 Mathematical model: our method

Our aim is mathematical and numerical analysis on a recent population management problem with an emphasis of viscosity solutions. This section presents our mathematical approach and derives basic properties of the present mathematical model.

2.1 Population dynamics

An infinite-horizon management problem of an animal population in a habitat is considered [21]. We assume that the decision-maker, the manager of the animal population, can reduce the animal population through intervention, and also assume that they are carried out in a much shorter timescale than that of the animal population dynamics, so that the impulsive control formalism is justified. The population in the habitat at the time t is denoted as \(X_{t}\), which is governed by a stochastic differential equation (SDE) with the fluctuation term defined in the Itô’s sense:

where \(\mu > 0\) is the intrinsic growth rate, \(\sigma > 0\) is the magnitude of stochastic fluctuation involved in the population dynamics, \(B_{t}\) is the 1-D standard Brownian motion defined on a usual complete probability space [25], \(\tau_{i}\) (\(i = 0,1,2, \ldots\) , \(\tau_{0} = 0\)) is the time when the intervention is performed to reduce the population and \(\zeta_{i} > 0\) represents the magnitude of the intervention, the total population of the killed animal, at the time \(\tau_{i}\). Whenever the intervention is performed, we assume the cost

where \(k_{1} > 0\) is the cost proportional to \(\zeta_{i}\) and \(k_{0} > 0\) is the fixed cost incurred regardless of \(\zeta_{i}\). In this model, both the timing \(\tau_{i}\) and the magnitude of the intervention \(\zeta_{i}\) are the control variables to be optimized.

2.2 Performance index

The performance index J is the expected net profit of the decision-maker subject to a discount:

with

where \(\delta > 0\) is the discount rate, and R, r, M and m are the positive constants. In the right-hand side of (3), the term \(RX_{s}^{M}\) represents the ecological utility provided by the existence of the animal, the term \(- rX_{s}^{m}\) represents the disutility by the existence of the animal, and the last summation term is the cost of the intervention. The net profit \(RX_{s}^{M} - rX_{s}^{m}\) is not monotone but concave with respect to \(X_{s}\). The relationship (4) means that the increase rate of the disutility by the existence of the animal is higher than that of the utility by the existence of the animal, and the condition \(0 < M < 1\) in (4) intrinsically means that the ecological services drastically change between the states where the population exists and where the population does not exist. This consideration is represented by the divergence of the derivative of \(RX_{s}^{M}\) with respect to \(X_{s}\) at the origin \(X_{s} = 0\).

Here, η represents the management policy defined by the timing and magnitude of the intervention

and is called an admissible control if it satisfies the conditions stated in Definition 2.1 in Onishi and Tsujimura [15], which are listed up in what follows:

and

2.3 Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality

Let \(\mathfrak{A}\) be the set of the admissible controls. The objective of the decision-maker is to find the optimal control \(\eta^{ *} \) such that

where \(V = V ( x )\) is the maximized performance index referred to as the value function. The dynamic programming principle [10] leads to a HJBQVI [14,15,16,17], which is hereafter simply referred to as the HJBQVI, as

with the differential operator \(\mathcal{L}\) and the intervention operator \(\mathcal {M}\) defined as

and

respectively, for generic sufficiently smooth \(W = W ( x )\). The boundary condition for the HJBQVI is \(V ( 0 ) = 0\), which means that no problem arises when there is no population. The left part in “min” operator in the HJBQVI (12) corresponds to the situation where no intervention should be performed, while the right part corresponds to the situation where the intervention should be performed immediately. The following lemma gives the upper and lower bound of V. The lemma shows that the value function is locally bounded.

Lemma 2.1

Proofs of all lemmas and theorems in the paper are in Appendices for the sake of brevity of the main body. In what follows, solutions to the HJBQVI complying with the condition (15) are explored.

2.4 Optimal control

Under the QVI controls (Definition 3.2 in Cadenillas [17])

and

the following threshold-type management policy with the threshold values x̄ and \(\underline{x}\) (\(\bar{x} > \underline{x}\)) is found to be optimal (Verification theorem, Theorem 3.1 in Cadenillas [17]):

-

(A)

If \(X_{t -} < \bar{x}\), then no intervention is performed. If \(X_{t -} = \bar{x}\), the intervention is immediately performed and \(X_{t -} \) is reduced to \(\underline{x}\) (\(X_{t} = \underline{x}\)).

-

(B)

If \(X_{0 -} > \bar{x}\), then \(X_{0 -} \) is immediately reduced to \(\underline{x}\) (\(X_{0} = \underline{x}\)) by the intervention, and follows (A).

With the thresholds x̄ and \(\underline{x}\), the optimal amount of the intervention \(\zeta^{ *} \) is

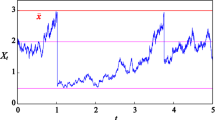

A sample path of the process \(X_{t}\) following the above-mentioned policy is plotted in Fig. 1. Note that Cadenillas [17] proved the verification theorem (Theorem 3.1 in the literature), which states that the solution to HJBQVI (12) under the QVI control (16) through (18) is in fact the value function (11) and the QVI control is the optimal impulse control. Thus, if we could solve the HJBQVI (12), then we are able to obtain the optimal impulse control.

3 Results and discussion on an exact solution

In this section, we present a candidate of the solution to the HJBQVI (12), which later turns out to be a viscosity solution. We assume the following conditions to derive a non-trivial exact viscosity solution [10]:

and

The inequality (20) means that the animal population does not become extinct without interventions. The relationship (21) and (22) means that the decision-maker manages the animal population from the sufficiently long-term perspectives.

Here, a formal exact solution to the HJBQVI (12) is presented, which is inspired from the impulse control models in the literature [15, 17, 21]. Let V̄ be a candidate of the solution to the HJBQVI (12). At first, we consider the situation with \(x < \bar{x}\), under which no intervention should be performed. In the HJBQVI (12), the equality [26]

has a solution

where

and

In (24), \(a_{1}x^{\beta_{ +}} + a_{2}x^{\beta_{ -}} \) is the general solution to \(\mathcal{L}\bar{V} = 0\) and \(A_{1}x^{M} + A_{2}x^{m}\) is a particular solution to (23). Assume \(a_{2} \ne 0\), then we have \(\lim_{x \to + 0}a_{2}x^{\beta_{ -}} = \pm \infty\) since \(\beta_{ -} < 0\). However, this contradicts the boundary condition \(\bar{V} ( 0 ) = 0\). Hence, \(a_{2} = 0\) holds. At last, the solution (24) becomes

where the notations \(a_{1} = a\) and \(\beta_{ +} = \beta\) are used.

For \(x \ge \bar{x}\) where the intervention should be performed immediately, by the HJBQVI (12), the condition

has to be satisfied. Consequently, a candidate of solutions to HJBQVI (12) is found as

where a, x̄ and \(\underline{x}\) are unknown at this stage.

Assume the following condition in the solution \(\bar{V} ( x )\) to determine its unknown coefficients [15, 16]:

-

(a)

Continuity of \(\bar{V} ( x )\) at \(x = \bar{x}\) (Value matching),

-

(b)

Continuity of \(\bar{V}' ( x )\) at \(x = \bar{x}\) (Smooth pasting),

-

(c)

Optimality of the thresholds x̄ and \(\underline{x}\) in (14).

Firstly, by (a), we have

By (b), we have

Finally, by (c)

namely, we have

holds. Substituting (28) into (31), (32), and (34), the following system of nonlinear equations governing the coefficients is derived:

where a, x̄ and \(\underline{x}\) are unknown. According to the conditions (a) and (b), the solution (30) is \(\bar{V} ( x ) \in C^{1} ( 0,\infty )\) and is twice differentiable except at \(x = \bar{x}\); namely, we have \(\bar{V} ( x ) \in C^{2} ( ( 0,\bar{x} ) \cup ( \bar{x},\infty ) )\). Thus, the solution \(\bar{V} ( x )\) is not a classical solution but a solution a.e.

For a, we have the following lemma, which immediately follows from the functional form of the exact solution (30) and Lemma 2.1. The following lemma is useful for determining the sign of the unknown coefficient involved in V̄.

Lemma 3.1

For a in (30), we have \(a \ge 0\).

4 Discussion on the system of nonlinear equations

4.1 Existence and uniqueness

In this subsection, we prove unique solvability of the system of nonlinear Eqs. (35) based on an analytical approach, which is inspired from the arguments in the literatures [15, 21]. Because our performance index contains a sum of two monomials of X, which is different from those in the literature, their procedure cannot be directly applied to our problem. The main objective of this section is to prove the following theorem that guarantees unique existence of the triplet of the unknown coefficients, with which we can completely determine V̄.

Theorem 4.1

There exists a unique triplet \(( a,\bar{x},\underline{x} )\) to the system of nonlinear equations (35).

Theorem 4.1 is proved in a step by step approach using a series of lemmas. Lemma 4.1 sharpens the result of Lemma 3.1.

Lemma 4.1

For a in (30), we have \(a \ne 0\).

According to Lemmas 3.1 and 4.1, we can assume \(a > 0\). With a fixed a, define the function g as

whose first derivative is

Lemma 4.2 presents a technical result on qualitative shape of \(g'\).

Lemma 4.2

\(g' ( x ) = 0\) has a unique zero \(x = \hat{x}\) such that \(0 < \hat{x} < \infty\).

Hereafter, we denote the unique x̂ in Lemma 4.2 as \(\hat{x} = \hat{x} ( a )\) to indicate its dependence on a. We show dependence of \(\hat{x} ( a )\) on a in the next lemma. The lemma indicates a monotone property of \(\hat{x} ( a )\).

Lemma 4.3

Next, we consider the profile of \(g ( x )\). The following lemma demonstrates that g is unimodal.

Lemma 4.4

\(g ( x )\) monotonically decreases for \(0 < x < \hat{x}\), takes its extremum at x̂, and monotonically increases for \(\hat{x} < x < \infty\). In addition, \(\lim_{x \to 0}g' ( x ) = - \infty\) and \(\lim_{x \to \infty} g' ( x ) = \infty\). See also Table 1.

The proof is omitted since it is by a direct calculation. In fact, by \(g' ( \hat{x} ) = 0\), we have

Thus, for a such that

there are two solutions to \(g ( x ) = 0\), \(x = \underline{x} ( a )\) and \(x = \bar{x} ( a )\). Note that \(\underline{x}\), x̂, and x̄ have to satisfy

It will turn out later that the inequality (40) is satisfied under without any additional conditions. Thus, hereafter, we assume (40).

In the next lemma, we show dependence of \(\underline{x} ( a )\) and \(\bar{x} ( a )\) on a. They are monotone with respect to a.

Lemma 4.5

Next, we consider the upper bound of a with which the above-mentioned \(\underline{x}\) and x̄ exist. Such an upper bound is denoted as â.

The next lemma shows that this upper bound in fact exists.

Lemma 4.6

There exists an upper bound of a with which \(\underline{x}\) and x̄ exist.

Hereafter, we represent the range of a as \(0 < a < \hat{a} ( k_{1} )\) to indicate its dependence on \(k_{1}\). Now, we prove that the pended inequality (40) is satisfied without any additional conditions.

Lemma 4.7

The inequality (40) is satisfied without any additional conditions to \(k_{1}\). Thus, there exist unique x̄ and \(\underline{x}\) which solve the system of nonlinear equations (35).

Now, we can prove uniqueness and existence of a.

Lemma 4.8

There exists a unique coefficient a solving the system of nonlinear equations (35) at least if \(k_{0}\) is sufficiently small.

We prove that the uniqueness and existence hold true also for not small \(k_{0}\).

Lemma 4.9

There exists a unique \(a^{ *} \) such that \(F ( a^{ *} ) = 0\) and \(0 < a^{ *} < \hat{a}\) solving (35). Here, \(F ( a )\) is the left hand side of (98).

Finally, from Lemmas 4.7 and 4.9, Theorem 4.1 immediately follows.

4.2 Optimality of the exact solution

Uniqueness of the exact solutions of the form (30) was proved in the previous sub-section. In this subsection, we show that the candidate of the solutions satisfies the HJBQVI (12). Let \(ax^{\beta} + A_{1}x^{M} + A_{2}x^{m}\) be \(\bar{V}_{l} ( x )\) and \(- k_{1} ( x - \underline{x} ) - k_{0} + a\underline{x}^{\beta} + A_{1}\underline{x}^{M} + A_{2}\underline{x}^{m}\) be \(\bar{V}_{r} ( x )\). By

the exact solution (30) is rewritten as

The following technical lemma is on the profile of V̄, necessary to consider property of V̄.

Lemma 4.10

With the help of Lemma 4.10, we show that the candidate solution actually satisfies the HJBQVI (12).

Theorem 4.2

The exact solution (30) satisfies the HJBQVI (12) a.e. for \(x \ge 0\).

According to Theorem 4.2, hereafter, we do not distinguish the candidate of the solutions to HJBQVI (30) and the value function (11). Namely, we have

Next, we prove a mathematical property of the exact solution (30). We prove that the exact solution (30) is a viscosity solution [10], which is an appropriate weak solution to degenerate elliptic and parabolic differential equations. The definition of viscosity solution is as follows.

Definition 4.1

Viscosity super-solution

A function \(V \in C [ 0,\infty )\) such that \(V ( 0 ) \ge 0\) satisfying (15) is a viscosity super-solution to the HJBQVI (12) if

for all \(x \in ( 0,\infty )\) and for all \(v \in C^{2} ( [ 0,\infty ) )\) such that \(v ( x ) = V ( x )\) and locally \(v \le V\) near x.

Viscosity sub-solution

A function \(V \in C [ 0,\infty )\) such that \(V ( 0 ) \le 0\) satisfying (15) is a viscosity sub-solution to the HJBQVI (12) if

for all \(x \in ( 0,\infty )\) and for all \(v \in C^{2} ( [ 0,\infty ) )\) such that \(v ( x ) = V ( x )\) and locally \(v \ge V\) near x.

Viscosity solution

A function \(V \in C [ 0,\infty )\) such that \(V ( 0 ) = 0\) satisfying (15) is a viscosity solution to the HJBQVI (12) if it is a viscosity super-solution as well as a viscosity sub-solution.

Viscosity property of the constructed exact solution is checked through Definition 4.1.

Theorem 4.3

The exact solution (30) is a viscosity solution to the HJBQVI (12).

From Theorems 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3, we can prove the following theorem, the most important theorem in this paper.

Theorem 4.4

The value function is the exact viscosity solution (30) to the HJBQVI (12) whose coefficients are uniquely determined from (35). Therefore, the solution of the form (30) is unique.

5 Numerical method for computing the coefficients

In the previous section, we showed that the coefficients \(( a,\underline{x},\bar{x} )\) are found uniquely; however, their exact values cannot be calculated analytically. We found that a dynamical system-based approach can be used for approximating the coefficients in a stable manner. The numerical method is presented and its convergence is analyzed, and its performance is examined in this section.

5.1 Dynamical system

Subtracting the middle equation in (35) from the below equation in (35) and solving for a yields

Substituting (49) into the middle equation of (35) leads to

and substituting (49) into the above equation of (35) then yields

By numerically solving the nonlinear Eqs. (50) and (51), x̄ and \(\underline{x}\) would be found. In this paper, the nonlinear Eqs. (50) and (51) with an artificial temporal term are proposed as the system of ODEs, a dynamical system, as

where

and

Let \(\bar{x} = \bar{x}^{ *} \) and \(\underline{x} = \underline{x}^{ *} \) satisfy (35). Then, we have

The system (52) is numerically integrated until the quasi-steady state is attained with the forward Euler method. The coefficient a can be calculated with (54) using the obtained \(\bar{x}^{ *} \) and \(\underline{x}^{ *} \). Thus, \(V ( x )\) (30) can be obtained. Note that there is a unique equilibrium point in the system (52) by Theorem 4.1 under the assumptions (20) through (22).

5.2 Stability of the equilibrium point

Based on the following easy but pivotal lemma, local stability of the equilibrium point \(( \bar{x}^{ *},\underline{x}^{ *} )\) is investigated.

Lemma 5.1

A \(2 \times 2\) matrix A is locally asymptotically stable if and only if

Let the Jacobian at \(( \bar{x},\underline{x} )\) be

By Lemma 5.1, the following theorem shows local stability of our dynamical system, supporting our approach to find the unknown coefficients through solving the dynamical system.

Theorem 5.1

The equilibrium point \(( \bar{x}^{ *},\underline{x}^{ *} )\) in (52) is locally asymptotically stable.

5.3 Numerical experiment

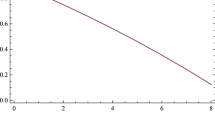

Finally, the system (52) is discretized with the conventional forward Euler method. The parameters are set as \(\mu = 1.7 \times 10^{ - 1}\) (1/year), \(\sigma = 5.3 \times 10^{ - 1}\) (1/year\(^{1/2}\)), \(m = 1.8\) (-), \(M = 0.5\) (-), \(\delta = 1.0\) (1/year), \(r = 5.0 \times 10^{ - 4}\) (-), \(R = 1.0 \times 10^{ - 1}\) (-), \(k_{0} = 1.0 \times 10^{1}\) (-) and \(k_{1} = 1.0 \times 10^{0}\) (-) [2]. These parameters satisfy the assumptions (20) through (22). The increment for the time integration is set as \(\Delta t = 0.01\) for stable temporal evolution of the system. The time integration marches until the error is under the error tolerance as

where n represents the time step and \(\varepsilon = 10^{ - 10}\) is the error tolerance. With the computed x̄ and \(\underline{x}\), a is calculated by (54). The initial estimations for the thresholds are set as \(\bar{x} = 7500\) and \(\underline{x} = 5500\). The computed thresholds are \(\bar{x}^{ *} = 7352.93\) and \(\underline{x}^{ *} = 5757.82\). The computed \(a^{ *} \) is \(a^{ *} = 4.39 \times 10^{ - 7} > 0\), which is consistent with Lemma 3.1. The same steady solution can be obtained for different initial estimations. Table 2 shows time evolution of the error, the residuals for each nonlinear Eqs. (35) as

and

during the computational period, and the computed thresholds. According to Table 2, the errors and the residuals monotonically decreases as the time marches and the computation ends at \(t = 5.5 \times 10^{7}\), indicating that the nonlinear Eqs. (35) are correctly solved; each residual is less than \(1.0 \times 10^{ - 8}\). In addition, we numerically confirmed that \(\operatorname{tr} A < 0\) and \(\det A > 0\), verifying the theoretical result.

6 Conclusions

This paper formulated the impulse control model of an animal population management, presented a candidate of the exact solutions of the HJBQVI, and proved its optimality and unique solvability within a certain class of solutions from a viscosity viewpoint. A numerical method to compute the coefficients for the exact solution to the HJBQVI was also presented and examined. Our future research will address analysis of time-dependent counterpart of the presented impulse control model. Such an extension would be necessary for dealing with seasonal population dynamics.

Abbreviations

- HJBQVI:

-

Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Quasi-Variational Inequality

- ODE:

-

Ordinary Differential Equation

References

Yoshioka H, Yaegashi Y. Stochastic optimization model of aquacultured fish for sale and ecological education. J Math Ind. 2017;7:8.

Yaegashi Y, Yoshioka H, Unami K, Fujihara M. A singular stochastic control model for sustainable population management of the fish-eating waterfowl Phalacrocorax carbo. J Environ Manag. 2018;219:18–27.

Yaegashi Y, Yoshioka H, Unami K, Fujihara M. Impulse and singular stochastic control approaches for management of fish-eating bird population. In: New trends in emerging complex real life problems. Berlin: Springer; 2018. p. 493–500.

Schley L, Dufrêne M, Krier A, Frantz AC. Patterns of crop damage by wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Luxembourg over a 10-year period. European Journal of Wildlife Research. 2008;54:589.

Turnipseed SG, Kogan M. Soybean entomology. Annu Rev Entomol. 1976;21:247–82.

Kameda K. Population increase of the Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo and measures to reduce its damage to the fisheries and forests of Lake Biwa. In: Kawanabe H, Nishino M, Maehata M, editors. Lake Biwa: interactions between nature and people. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 491–6.

van Eerden M, van Rijn S, Volponi S, Paquet JY, Carss D. Cormorants and the European environment: exploring cormorant status and distribution on a continental scale. In: INTERCAFE COST action 635 final report I. NERC/centre for ecology & hydrology on behalf of COST. 2012.

Doucette JL, Wissel B, Somers CM. Cormorant–fisheries conflicts: stable isotopes reveal a consistent niche for avian piscivores in diverse food webs. Ecol Appl. 2011;21:2987–3001.

White CR, Boertmann D, Gremillet D, Butler PJ, Green JA, Martin GR. The relationship between sea surface temperature and population change of great cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo breeding near disko bay. Greenland Ibis. 2011;153:170–4.

Pham H. Continuous-time stochastic control and optimization with financial applications. Berlin: Springer; 2009.

Insley MC. On the timing of non-renewable resource extraction with regime switching prices: an optimal stochastic control approach. 2015.

Lechuga GP. Optimal logistics strategy to distribute medicines in clinics and hospitals. J Math Ind. 2017;7:8.

Marheineke N, Cibis TM, Schiessl S, Pielmeier U. Optimal control of glucose balance in ICU patients based on GlucoSafe model. J Math Ind. 2014;4:3.

Øksendal B, Sulem A. Applied stochastic control of jump diffusions. Berlin: Springer; 2005.

Ohnishi M, Tsujimura M. An impulse control of a geometric Brownian motion with quadratic costs. Eur J Oper Res. 2006;168:311–21.

Tsujimura M, Maeda A. Stochastic control: theory and applications. Asakura Shoten. 2016. (in Japanese).

Cadenillas A. Optimal central bank intervention in the foreign exchange market. J Econ Theory. 1999;87:218–42.

Bensoussan A, Long H, Perera S, Sethi S. Impulse control with random reaction periods: a central bank intervention problem. Oper Res Lett. 2012;40:425–30.

Korn R. Portfolio optimisation with strictly positive transaction costs and impulse control. Finance Stoch. 1998;2:85–114.

Øksendal B, Sulem A. Optimal consumption and portfolio with both fixed and proportional transaction costs. SIAM J Control Optim. 2002;40:1765–90.

Øksendal B. Stochastic control problems where small intervention costs have big effects. Appl Math Optim. 1999;40:355–75.

Crandall MG, Ishii H, Lions PL. User’s guide to viscosity solutions of second order partial differential equations. Bull Am Math Soc. 1992;27:1–67.

Pham H. Optimal stopping of controlled jump diffusion processes: a viscosity solution approach. J Math Syst Estim Control. 1998;8:1–27.

Zhang S, Almost PD. Periodic viscosity solutions of nonlinear parabolic equations. Bound Value Probl. 2009;2009:873526.

Øksendal B. Stochastic differential equations. Berlin: Springer; 2003.

Kreyszig E. Advanced engineering mathematics. New York: Wiley; 2010. p. 69–72.

Chong E, Zak SH. An introduction to optimization. Algorithms. 1996;419:75–83.

Acknowledgements

JSPS Research Grant No. 17K15345 and No. 17J09125 support this research.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

JSPS Research Grant No. 17K15345 and No. 17J09125 support this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY and HY carried out the mathematical analysis. YY carried out the numerical computation. YY, HY, and KT wrote the paper. MF supervised and improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Proof of Lemma 2.1

If no intervention is performed (\(\tau_{1} = \infty\)), from the definition of the value function (11),

holds true. Since we have

by the property of geometric Brownian motion,

holds true. This is the lower bound of \(V ( x )\). Since for any \(X_{s}\), we have

and thus

Therefore, we have

Taking the expectation in both sides of (67) yields

Taking “sup” in the left hand side of (68) leads to

which is the upper bound of \(V ( x )\). □

Proof of Lemma 4.1

Assume \(a = 0\). From the middle and lower lines of (35), we have

The left hand side of (70) takes ∞ at \(x = 0\), monotonically decreases with respect to x and takes 0 at \(x = \infty\), while the right hand side of (70) takes \(- k_{1} < 0\) at \(x = 0\), monotonically increases with respect to x and takes −∞ at \(x = \infty\). According to the intermediate value theorem, (70) has a unique solution \(\stackrel{\frown}{x}\) such that \(0 < \stackrel{\frown}{x} < \infty\). Thus, when \(a = 0\), \(\stackrel{\frown}{x} = \bar{x} = \underline{x}\) and it is a contradiction. □

Proof of Lemma 4.2

The second derivative of (36) is

Since \(a\beta ( \beta - 1 ) ( \beta - 2 ) \ge 0\), \(A_{1}M ( M - 1 ) ( M - 2 ) \ge 0\) and \(A_{2}m ( m - 1 ) ( m - 2 ) \ge 0\), we have

Then, (37) can be rewritten as

which gives \(g' ( 0 ) = - \infty\) since \(2 - M > 0\). Define \(x = \hat{x}\) such that \(g' ( x ) = 0\). Then, from (73), we have

By the classical intermediate value theorem, (74) has a unique x̂ such that \(0 < \hat{x} < \infty\). □

Proof of Lemma 4.3

By differentiating (74) with respect to a,

is obtained. By using (71), (75) can be rewritten as

Since \(g'' ( x ) > 0\), we obtain

□

Proof of Lemma 4.5

From the lower of the system of nonlinear Eqs. (35),

holds true. Differentiating (78) with respect to a leads to

By using (73), (79) can be rewritten as

which is equivalent to

According to Table 1, we have

and thus

We can calculate dependence of \(\bar{x} ( a )\) to a in the similar manner as

Again according to Table 1, we have

and thus

The results (84) and (86) indicate that \(\underline{x}\) monotonically increases with respect to a, while x̄ monotonically decreases with respect to a. □

Proof of Lemma 4.6

According to (41) with \(a = \hat{a}\), we have

By (35) we have

Since \(g' ( \hat{x} ) = 0\) and \(y = \hat{x}\), the equality

holds true. Multiplying \(\beta - 1 > 0\) by (88) and subtracting (89) from it gives

Equation (90) is written as

where \(C_{1} > 0\) and \(C_{2} > 0\), which are constant and not dependent of \(k_{1}\). According to the classical intermediate value theorem, (91) has a unique solution \(y = \hat{y} ( k_{1} )\) such that \(0 < \hat{y} ( k_{1} ) < \infty\) and is not dependent of \(k_{1} > 0\) and a. By using \(\hat{y} ( k_{1} )\), from (88), we can calculate unique \(a = \hat{a} ( k_{1} )\). This is the upper bound of a. If \(a > \hat{a} ( k_{1} )\), \(\underline{x} ( a ) > \bar{x} ( a )\) holds true since \(\underline{x} ( \hat{a} ) = \bar{x} ( \hat{a} )\) and Lemma 4.5. This contradicts (41). Therefore, \(\hat{a} ( k_{1} )\) is the upper bound of a with which \(\underline{x}\) and x̄ exist. □

Proof of Lemma 4.7

By \(g' ( \hat{x} ) = 0\), we have

We introduce the function s:

whose first derivative is

Since \(\hat{x} = \bar{x} = \underline{x} = \hat{y}\) when \(a = \hat{a}\), we have

By (90), (95) becomes \(s ( \hat{a} ) = 0\). Since the first derivative of s is larger than 0, we have

It is proved that the inequality (40) is satisfied under without any additional conditions to \(k_{1}\). Thus, there exist unique two solutions to \(g ( x ) = 0\), \(\underline{x} ( a )\) and \(\bar{x} ( a )\) under without any additional conditions to \(k_{1}\). □

Proof of Lemma 4.8

From the upper of the system of nonlinear Eqs. (35),

holds true. Manipulating (97) yields

We define \(F ( a )\) as the left hand side of (98). Since \(\bar{x} = \underline{x} = y\) when \(a = \hat{a}\), \(F ( \hat{a} ) = k_{0} > 0\). Then, we have

Here, we used the middle and lower lines of (35). The second derivative of \(F ( a )\) is calculated as

In addition, we have

Notice that \(F ( 0 ) < F ( \hat{a} ) = k_{0}\) and thus when \(k_{0} = 0\), we have \(F ( 0 ) < F ( \hat{a} ) = 0\). Therefore, if \(k_{0}\) is sufficiently small, then there is a unique \(a^{ *} \) such that \(F ( a^{ *} ) = 0\) and \(0 < a^{ *} < \hat{a}\). □

Proof of Lemma 4.9

We investigate \(F ( 0 )\). At first, we investigate \(\lim_{a \to + 0}\bar{x} ( a )\) and \(\lim_{a \to + 0}\underline{x} ( a )\). From Lemma 4.5,

holds true. From the Lemma 4.5, we have

Assume \(\bar{x} ( 0 ) < \infty\). Under the limit \(a \to + 0\), we have \(a\beta \bar{x}^{\beta - 1} \to 0\). From the middle line of (35),

holds true. In addition, from the lower line of (35),

holds true. We define the following function

According to the classical intermediate value theorem, \(N ( x ) = 0\) has a unique solution \(x = \stackrel{\smile}{x}\) such that \(0 < \stackrel{\smile}{x} < \infty\). This indicates \(\underline{x} ( 0 ) = \bar{x} ( 0 ) = \stackrel{\smile}{x} < \infty\). From the upper of the system of nonlinear Eqs. (35), since \(\underline{x} ( 0 ) = \bar{x} ( 0 ) < \infty\), when \(a = 0\), we have \(k_{0} = 0\). This result contradicts \(k_{0} > 0\). Therefore, \(\bar{x} ( 0 ) = \infty\) holds true. We calculate \(F ( 0 )\) as

where \(c < \infty\) is a constant independent of a. From the middle line of (35), we have

Substituting (108) into (107) yields

and thus

Again, by the classical intermediate value theorem, there exists a unique \(a^{ *} \) such that satisfies \(F ( a^{ *} ) = 0\) and \(0 < a^{ *} < \hat{a}\) for any \(k_{0} > 0\). □

Proof of Lemma 4.10

From the middle and lower lines (35), the middle line of (45) is obvious. Since \(\bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} ( x ) + k_{1} = g ( x )\), according to Table 1, we have

and

These results shows that the upper and lower in (45) are satisfied. □

Appendix 2

This appendix contains the proofs of Theorems 4.2 and 4.3.

Proof of Theorem 4.2

We divide the domain into \(( 0,\bar{x} )\) and \([ \bar{x},\infty )\).

-

(1)

\(x \in ( 0,\bar{x} )\)

By the way of constructing the solution (23),

$$ \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) + Rx^{M} - rx^{m} = 0\quad \mbox{in } ( 0,\bar{x} ) $$(113)holds true. Thus, we should prove

$$\begin{aligned} &\mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) \\ &\quad = \sup _{\zeta > 0} \bigl[ - k_{1}\zeta - k_{0} + \bar{V}_{l} ( x - \zeta ) \bigr] - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) \le 0\quad \mbox{in } ( 0,\bar{x} ). \end{aligned}$$(114)When \(\zeta^{ *} > 0\), from the first order optimality condition [27] in “sup” operator in (14), \(\bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} ( x - \zeta^{ *} ) = - k_{1}\) holds true. From Theorem 4.1, the system of nonlinear Eqs. (35) has unique solution and we have \(x - \zeta^{ *} = \bar{x}\) or \(x - \zeta^{ *} = \underline{x}\). If \(x - \zeta^{ *} = \bar{x}\), \(x > \bar{x}\) holds true and this is a contradiction. Thus, we have \(\zeta^{ *} = x - \underline{x}\). When formally \(\zeta^{ *} = 0\),

$$ \mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) = -k_{0} \leq 0 $$(115)holds true. We further divide the domain into three parts as follows.

-

(a)

\(0 < x < \underline{x}\)

Assume \(\zeta^{ *} > 0\). Then, \(\zeta^{ *} = x - \underline{x} < 0\) holds true and this is a contradiction. Thus, formally \(\zeta^{ *} = 0\) holds true. From (115),

$$ \mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) = -k_{0} \leq 0 $$(116)holds true. This result shows that the condition is satisfied in \(0 < x < \underline{x}\).

-

(b)

\(x = \underline{x}\)

Assume \(\zeta^{ *} > 0\). Then, \(\zeta^{ *} = \underline{x} - \underline{x} = 0\) holds true and this is a contradiction. Thus, formally \(\zeta^{ *} = 0\) holds true. From (115),

$$ \mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{l} ( \underline{x} ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( \underline{x} ) = -k_{0} \leq 0 $$(117)holds true. This result shows that the condition is satisfied at \(x = \underline{x}\).

-

(c)

\(\underline{x} < x < \bar{x}\)

Assume \(\zeta^{ *} > 0\). Then, we have \(\zeta^{ *} = x - \underline{x} > 0\) in this case and the assumption is in fact valid. We then obtain

$$ \begin{aligned}[b] \mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) &= \sup_{\zeta > 0} \bigl[ - k_{1}\zeta - k_{0} + \bar{V}_{l} ( x - \zeta ) \bigr] - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) \\ &= - k_{1} ( x - \underline{x} ) - k_{0} + \bar{V}_{l} ( \underline{x} ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ). \end{aligned} $$(118)We define the following function as

$$ T ( x ) = - k_{1} ( x - \underline{x} ) - k_{0} + \bar{V}_{l} ( \underline{x} ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ). $$(119)From (43),

$$ T ( \bar{x} ) = - k_{1} ( \bar{x} - \underline{x} ) - k_{0} + \bar{V}_{l} ( \underline{x} ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( \bar{x} ) = 0 $$(120)holds true and we have \(T' ( x ) = - k_{1} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} ( x )\). From (45),

$$ T' ( x ) = - k_{1} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} ( x ) > 0\quad \mbox{in } \underline{x} < x < \bar{x} $$(121)and thus

$$ \mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ) = T ( x ) < 0\quad \mbox{in } \underline{x} < x < \bar{x}. $$(122)

-

(a)

-

(2)

\(x \in [ \bar{x},\infty )\)

By the way of constructing the solution (29),

$$ \mathcal {M}\bar{V}_{r} - \bar{V}_{r} = 0\quad \mbox{in } [ \bar{x},\infty ) $$(123)holds true. Thus, we should prove

$$ \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{r} + Rx^{M} - rx^{m} \le 0 $$(124)in \(( 0,\bar{x} )\). For \(\bar{V}_{l} ( x )\),

$$ \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{l} ( x ) + Rx^{M} - rx^{m} = 0\quad \mbox{in } [ \bar{x},\infty ) $$(125)holds true. Substituting (125) into \(\mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{r} + Rx^{M} - rx^{m}\) yields

$$ \begin{aligned}[b] \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{r} + Rx^{M} - rx^{m} &= \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{r} - \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{l} \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\sigma^{2}x^{2} \bigl( \bar{V}_{r}^{\prime \prime} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime \prime} \bigr) + \mu x \bigl( \bar{V}'_{r} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} \bigr) - \delta ( \bar{V}_{r} - \bar{V}_{l} ) \end{aligned}. $$(126)Since \(\bar{V}_{r}^{\prime \prime} = 0\) and \(\bar{V}_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( x ) = g' ( x )\), by Table 1, we have \(\bar{V}_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( x ) = g' ( x ) > 0\) in \(x \ge \bar{x}\) and thus

$$ \bar{V}_{r}^{\prime \prime} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime \prime} < 0. $$(127)Since \(\bar{V}_{r}^{\prime} = - k_{1}\) and \(\bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} > - k_{1}\) from Lemma 4.10,

$$ \bar{V}_{r}^{\prime} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} < 0 $$(128)holds true. We define the following function as

$$ Q ( x ) = \bar{V}_{r} - \bar{V}_{l} = \bar{V}_{l} ( \bar{x} ) - k_{1} ( x - \bar{x} ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( x ), $$(129)and

$$ Q ( \bar{x} ) = \bar{V}_{l} ( \bar{x} ) - \bar{V}_{l} ( \bar{x} ) = 0 $$(130)at \(x = \bar{x}\). The first derivative of (129) is calculated as

$$ Q' ( x ) = - k_{1} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} ( x ). $$(131)Since \(\bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} \ge - k_{1}\) in \(x \ge \bar{x}\) from Lemma 4.10,

$$ Q' ( x ) = - k_{1} - \bar{V}_{l}^{\prime} ( x ) \le 0 $$(132)holds true. Thus,

$$ \bar{V}_{r} - \bar{V}_{l} = Q ( x ) \le 0\quad \mbox{in } x \ge \bar{x}. $$(133)Therefore, from (127), (128), and (133),

$$ \mathcal{L}\bar{V}_{r} + Rx^{M} - rx^{m} = \mathcal{L} ( \bar{V}_{r} - \bar{V}_{l} ) < 0\quad \mbox{in } x \ge \bar{x}, $$(134)leading to (124).

□

Proof of Theorem 4.3

Except at \(x = \bar{x}\), it is clear that the exact solution (30) is a viscosity solution since the exact solution (30) is of the \(C^{2}\)-class. Thus, we only have to investigate the viscosity property at the point \(x = \bar{x}\). We prove V is a sub and supersolution at \(x = \bar{x}\).

Since \(V_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( x ) = g' ( x )\) in \(x < \bar{x}\), by Table 1, we have

holds true. In addition, since the exact solution is linear in \(x > \bar{x}\), \(V_{r}^{\prime \prime} ( \bar{x} + 0 ) = 0\) holds true. From the HJBQVI (12),

holds true.

-

(a)

For viscosity sub-solution

Let v be a test function \(v ( \bar{x} ) = V ( \bar{x} )\) and \(v ( x ) \ge V ( x )\) near x̄. We should prove

$$ \min \bigl\{ - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m},v ( \bar{x} ) - \mathcal {M}v ( \bar{x} ) \bigr\} \le 0. $$(137)From the HJBQVI (12),

$$ \min \bigl\{ - \mathcal{L}V ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m},V ( \bar{x} ) - \mathcal {M}V ( \bar{x} ) \bigr\} = 0 $$(138)holds true. From the definition of the test function and \(V \in C^{1} ( 0, + \infty )\), \(v' ( x ) = V' ( x )\) holds true near x̄. This leads to

$$ V ( \bar{x} ) - \mathcal {M}V ( \bar{x} ) = v ( \bar{x} ) - \mathcal {M}v ( \bar{x} ) = 0, $$(139)showing that

$$\begin{aligned} &\min \bigl\{ - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m},v ( \bar{x} ) - \mathcal {M}v ( \bar{x} ) \bigr\} \\ &\quad = \min \bigl\{ - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m},0 \bigr\} \le 0. \end{aligned}$$(140) -

(b)

For viscosity super-solution

Let v be a test function such that \(v ( \bar{x} ) = V ( \bar{x} )\) and \(v ( x ) \le V ( x )\) near x̄. We have to prove

$$ \min \bigl\{ - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m},v ( \bar{x} ) - \mathcal {M}v ( \bar{x} ) \bigr\} \ge 0. $$(141)Since \(v ( x ) = V ( x )\) and \(v' ( x ) = V' ( x )\), we have

$$ \begin{aligned}[b] - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m} &= \delta v - \mu \bar{x}v' - \frac{\sigma^{2}\bar{x}^{2}}{2}v'' - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m} \\ &= \delta V - \mu \bar{x}V' - \frac{\sigma^{2}\bar{x}^{2}}{2}v'' - R\bar{x}^{M} + r\bar{x}^{m} \end{aligned}. $$(142)By (136), we also have

$$ \delta V - \mu \bar{x}V' - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m} = \frac{\sigma^{2}\bar{x}^{2}}{2}V_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( \bar{x} - 0 ). $$(143)Combining (142) and (143) gives

$$ \begin{aligned}[b] - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m} &= \delta V - \mu \bar{x}V' - \frac{\sigma^{2}\bar{x}^{2}}{2}v'' - R\bar{x}^{M} + r \bar{x}^{m} \\ &= \frac{\sigma^{2}\bar{x}^{2}}{2} \bigl\{ V_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( \bar{x} - 0 ) - v'' ( \bar{x} ) \bigr\} . \end{aligned} $$(144)Since \(V - v \ge 0\) near x̄ and \(V ( \bar{x} ) = v ( \bar{x} )\), we arrive at the inequality

$$ V_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( \bar{x} - 0 ) - v'' ( \bar{x} ) \ge 0, $$(145)leading to

$$ - \mathcal{L}v ( \bar{x} ) - R\bar{x}^{M} + r\bar{x}^{m} \ge 0. $$(146)Thus, the solution to the HJBQVI (12) is a viscosity solution at \(x = \bar{x}\). Therefore, the exact solution (30) is a viscosity solution.

□

Appendix 3

This appendix presents the proof of Theorem 5.1.

Proof of Theorem 5.1

The signs of trA and detA at \(( \bar{x}^{ *},\underline{x}^{ *} )\) are firstly analyzed. Since \(V_{l}^{\prime \prime} ( x ) = g' ( x )\) in \(x < \bar{x}\), Table 1 leads to

By differentiating (54) with respect to x̄, we have

which can be rewritten as

when \(( \bar{x},\underline{x} ) = ( \bar{x}^{ *},\underline{x}^{ *} )\) by (37). Then, we have

In the same way, by (147), differentiating (54) with respect to \(\underline{x}\) gives

The components of the Jacobian (57) are calculated as

and

By (150) and (151), the signs of the components at the equilibrium point are calculated as

and

Hence, we have (56). Therefore, by Lemma 5.1, the equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable. If the initial estimation of \(( \bar{x},\underline{x} )\) is sufficiently near the equilibrium point \(( \bar{x}^{ *},\underline{x}^{ *} )\), the solution of the system of the ODEs (52) converges to \(( \bar{x}^{ *},\underline{x}^{ *} )\). □

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaegashi, Y., Yoshioka, H., Tsugihashi, K. et al. An exact viscosity solution to a Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman quasi-variational inequality for animal population management. J.Math.Industry 9, 5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13362-019-0062-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13362-019-0062-y