Abstract

Background

Arcobacter species, particularly A. butzleri, but also A. cryaerophilus constitute emerging pathogens causing gastroenteritis in humans. However, isolation of Arcobacter may often fail during routine diagnostic procedures due to the lack of standard protocols. Furthermore, defined breakpoints for the interpretation of antimicrobial susceptibilities of Arcobacter are missing. Hence, reliable epidemiological data of human Arcobacter infections are scarce and lacking for Germany. We therefore performed a 13-month prospective Arcobacter prevalence study in German patients.

Results

A total of 4636 human stool samples was included and Arcobacter spp. were identified from 0.85% of specimens in 3884 outpatients and from 0.40% of specimens in 752 hospitalized patients. Overall, A. butzleri was the most prevalent species (n = 24; 67%), followed by A. cryaerophilus (n = 10; 28%) and A. lanthieri (n = 2; 6%). Whereas A. butzleri, A. cryaerophilus and A. lanthieri were identified in outpatients, only A. butzleri could be isolated from samples of hospitalized patients. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter isolates revealed high susceptibilities to ciprofloxacin, whereas bimodal distributions of MICs were observed for azithromycin and ampicillin.

Conclusions

In summary, Arcobacter including A. butzleri, A. cryaerophilus and A. lanthieri could be isolated in 0.85% of German outpatients and ciprofloxacin rather than other antibiotics might be appropriate for antibiotic treatment of infections. Further epidemiological studies are needed, however, to provide a sufficient risk assessment of Arcobacter infections in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Arcobacter belongs to the family of Campylobactereaceae as initially proposed by Vandamme et al. [1]. To date, 29 Arcobacter species have been identified [2, 3]. The Gram-negative, motile bacteria are aerotolerant and able to grow at temperatures below 30 °C. Arcobacter have been isolated from various sources, such as animals, food products of animal origin, vegetables and environmental waters [4,5,6]. In animals, Arcobacter infections sometimes result in reproductive disorders, mastitis, and diarrhea, whereas the bacteria can also be isolated from healthy carriers [4]. In humans, severe cases following Arcobacter infection have been reported including prolonged watery gastroenteritis with abdominal cramps, bacteremia, endocarditis and peritonitis [5, 7, 8]. A. butzleri followed by A. cryaerophilus are the predominant species isolated from human specimens, while human infections with A. skirrowii or A. thereius have only been rarely reported [9,10,11]. Nevertheless, the clinical relevance of human Arcobacter infections is still under debate. Given that the isolation and identification of Arcobacter may fail in routine diagnostic settings, robust epidemiological data on Arcobacter-induced morbidities are limited. Thus far, Arcobacter prevalences of 0.2–3.6% have been reported for humans [4, 12]. In a recent Belgian study, Arcobacter was the fourth most common pathogenic agent in diarrheal outpatients [10]. To date, there are no Arcobacter prevalence data for Germany, although since 2002, Arcobacter species such as A. butzleri and A. cryaerophilus have been classified as serious hazards to human health by the International Commission on Microbiological Specification for Foods [13].

Most infections with Arcobacter appear to be self-limiting and do not require antimicrobial treatment; nevertheless, in cases of severe and persistent symptoms antibiotic treatment may be indicated [14]. Several classes of antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines and aminoglycosides have been considered for treatment of Arcobacter infections [5]. However, a recent meta-regression analysis revealed an emerging resistance of Arcobacter species against various antibiotics including fluoroquinolones [15]. Therefore, the objective of the present prospective study was (i) to determine the prevalence of Arcobacter spp. in human stool samples in Germany and (ii) to assess the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the isolates.

Results

Prevalence of Arcobacter spp. in human stool samples

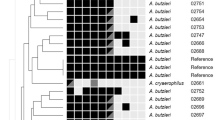

In the present study, a total of 4636 human stool samples were included. By using Arcobacter-specific isolation procedures, Arcobacter spp. were detected in 33 samples (0.85%) obtained from 3884 outpatients and in 3 specimens (0.40%) from 752 hospitalized patients (Table 1). Of the 33 isolates, 21 were identified as A. butzleri and 10 as A. cryaerophilus by multiplex PCR, while rpoB sequencing revealed that two of the putative A. butzleri isolates belong to the species A. lanthieri. All three Arcobacter species were isolated from outpatients samples, whereas only A. butzleri was isolated from hospitalized specimens. Overall, A. butzleri was the most prevalent species, followed by A. cryaerophilus and A. lanthieri.

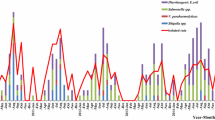

For a subgroup of the outpatients study population (n = 2257), data on other bacterial pathogens were available. While an enrichment step was used for the isolation of Yersinia and Salmonella, the isolation of Campylobacter was performed without enrichment. Within this subgroup Campylobacter spp. (4.39%) were the most frequently detected bacterial pathogens, followed by Salmonella enterica (0.75%), and Yersinia enterocolitica (0.09%) (Fig. 1). Notably in this subgroup, a twofold higher (0.97%) Arcobacter prevalence was determined by specific Arcobacter enrichment procedures compared to the prevalence determined by the routine diagnostic method for Campylobacter without enrichment (0.49%).

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Arcobacter isolates

For antimicrobial susceptibility testing of human Arcobacter isolates, six antibiotics were selected. Overall, our results revealed normally distributed minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) among Arcobacter spp. for erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and tetracycline, while a bimodal distribution for azithromycin and ampicillin was apparent (Fig. 2). For erythromycin, MICs (ranging from 0.5 to 32.0 µg/ml; Table 2) were distributed around the epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF) for C. jejuni (4 µg/ml; Fig. 2), while MICs for azithromycin were distributed above the ECOFF of C. jejuni (0.25 µg/ml; Fig. 2), ranging from 0.5 to 64.0 µg/ml (Table 2). Elevated MICs for azithromycin (> 8 µg/ml; Fig. 2) were determined for 50% of A. butzleri and 10% of A. cryaerophilus isolates (Table 2). The majority of all isolates (86%; Table 2) displayed high susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC ≤ 1 µg/ml; Fig. 2), whereas MIC ≥ 4 µg/ml were determined for 2/24 (8%) of A. butzleri and 3/10 (30%) of A. cryaerophilus isolates (Table 2). Only MICs below the ECOFF for C. jejuni (2 µg/ml) were determined for gentamicin, with no species differences (Fig. 2, Table 2). The MICs for ampicillin were bimodally distributed around the ECOFF of C. jejuni (8 µg/ml; Fig. 2) and 10/24 (42%) of A. butzleri and 2/10 (20%) of A. cryaerophilus isolates displayed elevated MICs (> 8 µg/ml; Fig. 2, Table 2). For tetracycline, MICs of all Arcobacter spp. isolates were distributed around the ECOFF for C. jejuni (1 µg/ml; Fig. 2), whereas the MICs determined for both A. lanthieri isolates were distributed within the ranges described for the other two species (Table 2).

Discussion

Arcobacter prevalence in human stool samples

This is the first prospective study addressing the prevalence of Arcobacter in stool samples from outpatients and hospitalized patients in Germany by applying an Arcobacter-specific detection method. Overall, Arcobacter spp. were isolated from 36 out of a total of 4636 (0.77%) examined specimens. This isolation rate is in concordance with studies from New Zealand and Belgium, where Arcobacter spp. were detected in 0.9% (12/1380) and 1.31% (89/6774) of human diarrheal fecal samples respectively [10, 20], whereas slightly different prevelances (as low as 0.2 or up to 3.6%) were found in other studies from Belgium, Turkey, Portugal, India and Chile [12, 21,22,23,24]. These differences could be attributed to various factors, such as patient populations, geographical aspects, examined sample sizes, and in particular, to the different microbiological methods applied. The impact of the detection method has been demonstrated in several studies [25,26,27,28]. The authors each compared different cultural isolation strategies with varying incubation and medium conditions revealing differences in Arcobacter isolation frequency ranging from 7% to 36%. Notably, our study revealed a higher Arcobacter prevalence in an analyzed subgroup by using Arcobacter-specific enrichment (0.97%) than determined by non-specific methods used in the three routine laboratories (0.49%). Future studies should address whether patients with Arcobacter spp. at low quantities that can only be detected by applying specific enrichment methods differ clinically from those patients in whom the pathogen is easily detected within the routine culture-based procedures.

Furthermore, we determined a higher Arcobacter prevalence in stool samples of outpatients than of hospitalized patients (i.e., 0.85% (33/3884) and 0.40% (3/752), respectively). Thus, in most patients, Arcobacter spp. most likely do not cause serious infections requiring hospitalization. Likewise, in a previous German study, patients who were hospitalized for severe gastroenteritis (n = 104) were found to be positive mainly for norovirus or Campylobacter spp.; in contrast, no Arcobacter was isolated by using routine diagnostics [29].

Among the 36 Arcobacter isolates obtained in our study, A. butzleri was the most prevalent species (n = 24) followed by A. cryaerophilus (n = 10), which is in line with other studies [10, 21, 24]. In addition, to best of our knowledge, this is the first report of A. lanthieri isolation from human specimens (n = 2) which might point towards its role as gastrointestinal pathogen. However, the applied selective enrichment media as well as the multiplex PCR are validated for the detection of the three species A. butzleri, A. cryaerophilus and A. skirrowii only, and could therefore bias the result according to species diversity [16, 18].

Overall, in the analyzed subgroup Arcobacter spp. were the second most frequently isolated pathogens (0.97%) after Campylobacter spp. (4.39%), followed by Salmonella enterica (0.75%). Our results are supported by a previous study demonstrating Arcobacter spp. as fourth most commonly isolated pathogens from diarrheal patients (1.31%), after Campylobacter spp. (5.61%), Salmonella spp. (2.04%) and C. difficile (1.61%), albeit prevalences of the enteropathogens were higher than in our study [10].

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Data regarding antimicrobial susceptibilities of Arcobacter spp. are scarce, mainly due to missing standardized protocols and defined breakpoints, which makes it difficult to interpret results and to define antimicrobial resistance. In previous studies, MIC results have been compared with breakpoints for Enterobacteriaceae or Staphylococcus spp. as defined by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), with breakpoints for Campylobacter as defined by the U.S. National Resistance Monitoring System criteria or with EUCAST breakpoints for Enterobacteriaceae, Campylobacter or non-species related breakpoints [5, 30, 31]. In our study, we compared the MICs with ECOFFs defined by EUCAST for C. jejuni [32]. For ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and ampicillin the C. jejuni ECOFFs appear to apply for Arcobacter as well as previously proposed by Riesenberg et al. [33]. However, our data suggest that Arcobacter ECOFFs for erythromycin, tetracycline and azithromycin may be higher than those of C. jejuni. All of our isolates displayed MICs for azithromycin above the ECOFF of C. jejuni (0.25 µg/ml), which, however, is comparable with data from a Belgian study [34]. Although erythromycin and azithromycin are both macrolides, the bimodal distribution for azithromycin but not for erythromycin was remarkable. Van den Abeele et al. have also detected MICs > 8 µg/ml for azithromycin in 50% of A. butzleri isolates, which is in line with our results [34]. Likewise, other studies revealed elevated MICs for azithromycin in up to 95% of A. butzleri and in 20% of A. cryaerophilus strains isolated from poultry products [30, 35]. Similar to our results, other studies on antimicrobial susceptibility revealed also low MICs for Arcobacter spp. to erythromycin whereas some studies reported resistance rates up to 62% [5, 36, 37]. In contrast to our study, those studies used disc diffusion assays with 15 µg/disc and applied resistance criteria for Enterobacteriaceae according to CLSI 2010. In Campylobacter, there is usually cross-resistance between azithromycin and erythromycin. Single isolates, however, may display susceptibility to erythromycin and resistance to azithromycin, and whole genome sequencing analysis revealed an amino acid substitution in ribosomal protein L22 (leading to azithromycin resistance), but no mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, which explains the susceptibility to erythromycin [38]. Further analyses are needed to determine the genomic background being responsible for the divergent MIC distributions observed by us for Arcobacter spp.

As mentioned before, 86% of the investigated Arcobacter isolates showed low MICs for ciprofloxacin ranging from 0.032–0.50 µg/ml, which is further supported by a recent study reporting ciprofloxacin susceptibility for all tested Arcobacter butzleri isolates [36]. In contrast, clinical Campylobacter isolates displayed high resistance rates (MICs ≥ 4 µg/ml) ranging from 45 to 71.4% [39, 40]. Notably, we found elevated MICs for ciprofloxacin predominantly in A. cryaerophilus strains similar to a Belgian study [34]. Thus, ciprofloxacin might be the drug of choice, if antibiotic treatment of A. butzleri-infection is required.

In accordance with our data, only low resistance rates from 0–4% of Arcobacter spp. to gentamicin have been reported before [36]. Similarly, susceptibility to tetracycline might be common, although one recent study from retail food in Portugal demonstrated high resistance (95%) in A. butzleri [5, 41]. Furthermore, 42% of our A. butzleri isolates displayed high MICs for ampicillin (24–64 µg/ml), which is similar to previous studies where 50 to 100% isolates with high ampicillin MICs have been shown [20, 22, 31, 34].

Conclusions

In summary, Arcobacter spp. were not rare in our study and could be isolated more often from outpatients than from hospitalized patients. Furthermore, A. lanthieri was identified in fecal samples from human patients for the first time. Results from antimicrobial susceptibility testing indicate that Arcobacter spp. might be more susceptible to fluoroquinolones than to macrolides, particularly azithromycin. Future studies should provide reliable risk assessments of Arcobacter infections in humans.

Methods

Isolation of Arcobacter spp

During a 13-month survey (from October 2017 until October 2018) 4636 stool samples were collected at three microbiological diagnostic laboratories in Berlin, Germany. Only stool samples submitted for the detection of bacterial enteropathogens were included. Given that samples were pseudonymized before performance, no detailed patient information were available. Samples were stored up to 1 week at 4 °C by the diagnostic laboratories until Arcobacter specific isolation procedures were performed in our laboratories.

For detection of Arcobacter spp., isolation was carried out using selective enrichment media according to a study done by van Driessche et al. [16]. All incubation steps were performed at 30 °C under microaerobic conditions unless stated differently. Briefly, 1 g of stool samples was diluted at 1:10 with Arcobacter broth (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) (24 g/l) containing 5% lysed horse blood, 5´-fluorouracil (100 mg/l), amphotericin B (10 mg/L), novobiocin (32 mg/l), cefoperazone (16 mg/l) and trimethoprim (64 mg/l) (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). The samples were mixed thoroughly, and incubated for 72 h. Samples were then plated onto Arcobacter selective plates (as described above except lysed horse blood) and incubated for 48 h. Suspect colonies (i.e., small round white or grey colonies) were transferred onto Mueller–Hinton agar plates (Oxoid) supplemented with 5% sheep blood (MHB) and incubated for 48 h.

PCR analyses

The genomic DNA of these isolates was extracted by using a modified chelex-based method described by Karadas et al. [17]. Briefly, a small amount of colony material was washed in 250 µl TE buffer (1 mM Tris/HCL, pH 8.0, 100 µM EDTA; Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000×g for 6 min. Pellets were resuspended in 250 µl 5% Chelex (BioRad, Munich, Germany) followed by incubation at 56 °C for 1 h and subsequently at 95 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation at 16,000xg for 5 min, 100 µl of the supernatant were stored at 4 °C or directly used to identify the isolates by multiplex PCR according to Houf et al. [18]. Briefly, PCR reaction mixture contained 1x PCR buffer (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands), 2.8 mM MgCl2 (Qiagen), 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), 0.75 U Taq polymerase (Qiagen), 1 µM of each primer ARCO R, BUTZ F, CRY 1, and CRY 2 and 0.5 µM of primer SKIR F, and 2 µl template DNA in a total reaction volume of 25 µl. PCR samples were subjected to an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 32 amplification cycles, consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 61 °C for 45 s and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s, and subsequently 5 min at 72 °C for final extension. DNA of A. butzleri (CCUG 30485), A. cryaerophilus (DSM 7289) and A. skirrowii (CCUG 10374) were used as control. Amplified products were separated using gel electrophoresis and visualized under UV light by GRgreen staining.

For verification at species level, all positive isolates were analyzed by rpoB sequencing according to a study done by Korczak et al. [19]. Briefly, a 50 µl PCR-mixture contained 4 µl template DNA, 1x PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1 U Taq polymerase and 0.4 µM of each primer CamrpoB-L and RpoB-R. PCR reaction conditions were 95 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s and subsequently a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplified products were separated using gel electrophoresis and visualized under UV light by GRgreen staining. Amplicons were purified using GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced by GATC (Eurofins GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany). Species were identified by comparing the rpoB sequences with BLAST database (NCBI).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Susceptibility testing of Arcobacter spp. isolates to azithromycin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, erythromycin and tetracycline was performed using the gradient strip diffusion method (E-testTM, bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany). Briefly, Arcobacter isolates grown on MHB agar plates (30 °C, microaerobic, 48 h) were precultured overnight in brucella broth (BB; 30 °C, microaerophilic) to receive an inoculum of approximately 1 x 108 colony forming units (CFU) per ml. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as control and cultured likewise, but at 37 °C and in aerobic atmosphere. For testing the slower growing A. cryaerophilus isolates, three overnight cultures per isolate were pooled (6 ml), centrifuged, and the pellets resuspended in 600 µl BB in order to receive similar inoculum concentrations. MHB agar plates were inoculated with 100 µl of preculture and incubated after application of gradient strips at 30 °C for 48 h under microaerobic conditions (37 °C and aerobic for E. coli).

Statistical analysis

For calculating significant differences in prevalences of Arcobacter in outpatients and hospitalized patients, the Chi squared test and the Fisher’s exact test were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.04; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, US). Differences were considered significant at values of P < 0.05.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Vandamme P, Falsen E, Rossau R, Hoste B, Segers P, Tytgat R, et al. Revision of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella taxonomy: emendation of generic descriptions and proposal of Arcobacter gen. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41(1):88–103.

Perez-Cataluna A, Collado L, Salgado O, Lefinanco V, Figueras MJ. A polyphasic and taxogenomic evaluation uncovers arcobacter cryaerophilus as a species complex that embraces four genomovars. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:805.

Perez-Cataluna A, Salas-Masso N, Figueras MJ. Arcobacter lacus sp. nov. and Arcobacter caeni sp. nov., two novel species isolated from reclaimed water. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;69(11):3326–31.

Collado L, Figueras MJ. Taxonomy, epidemiology, and clinical relevance of the genus Arcobacter. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(1):174–92.

Ferreira S, Queiroz JA, Oleastro M, Domingues FC. Insights in the pathogenesis and resistance of Arcobacter: a review. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42(3):364–83.

Ramees TP, Dhama K, Karthik K, Rathore RS, Kumar A, Saminathan M, et al. Arcobacter: an emerging food-borne zoonotic pathogen, its public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control—a comprehensive review. Vet Q. 2017;37(1):136–61.

Arguello E, Otto CC, Mead P, Babady NE. Bacteremia caused by arcobacter butzleri in an immunocompromised host. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(4):1448–51.

Figueras MJ, Levican A, Pujol I, Ballester F, Rabada Quilez MJ, Gomez-Bertomeu F. A severe case of persistent diarrhoea associated with Arcobacter cryaerophilus but attributed to Campylobacter sp. and a review of the clinical incidence of Arcobacter spp. N Microbes N Infect. 2014;2(2):31–7.

Samie A, Obi CL, Barrett LJ, Powell SM, Guerrant RL. Prevalence of Campylobacter species, Helicobacter pylori and Arcobacter species in stool samples from the Venda region, Limpopo, South Africa: studies using molecular diagnostic methods. J Infect. 2007;54(6):558–66.

Van den Abeele AM, Vogelaers D, Van Hende J, Houf K. Prevalence of Arcobacter species among humans, Belgium, 2008–2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(10):1731–4.

Wybo I, Breynaert J, Lauwers S, Lindenburg F, Houf K. Isolation of Arcobacter skirrowii from a patient with chronic diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(4):1851–2.

Fernandez H, Villanueva MP, Mansilla I, Gonzalez M, Latif F. Arcobacter butzleri and A. cryaerophilus in human, animals and food sources, in southern Chile. Braz J Microbiol. 2015;46(1):145–7.

ICMSF ICoMSfF. p 171. In: Tompkin RB, editor. Microbiological testing in food safety management, vol. 7. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002.

Prouzet-Mauleon V, Labadi L, Bouges N, Menard A, Megraud F. Arcobacter butzleri: underestimated enteropathogen. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(2):307–9.

Ferreira S, Luis A, Oleastro M, Pereira L, Domingues FC. A meta-analytic perspective on Arcobacter spp. antibiotic resistance. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;16:130–9.

van Driessche E, Houf K, van Hoof J, De Zutter L, Vandamme P. Isolation of Arcobacter species from animal feces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229(2):243–8.

Karadas G, Sharbati S, Hanel I, Messelhausser U, Glocker E, Alter T, et al. Presence of virulence genes, adhesion and invasion of Arcobacter butzleri. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;115(2):583–90.

Houf K, Tutenel A, De Zutter L, Van Hoof J, Vandamme P. Development of a multiplex PCR assay for the simultaneous detection and identification of Arcobacter butzleri, Arcobacter cryaerophilus and Arcobacter skirrowii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;193(1):89–94.

Korczak BM, Stieber R, Emler S, Burnens AP, Frey J, Kuhnert P. Genetic relatedness within the genus Campylobacter inferred from rpoB sequences. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2006;56(5):937–45.

Mandisodza O, Burrows E, Nulsen M. Arcobacter species in diarrhoeal faeces from humans in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2012;125(1353):40–6.

Ferreira S, Julio C, Queiroz JA, Domingues FC, Oleastro M. Molecular diagnosis of Arcobacter and Campylobacter in diarrhoeal samples among Portuguese patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(3):220–5.

Kayman T, Abay S, Hizlisoy H, Atabay HI, Diker KS, Aydin F. Emerging pathogen Arcobacter spp. in acute gastroenteritis: molecular identification, antibiotic susceptibilities and genotyping of the isolated arcobacters. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1439–44.

Patyal A, Rathore RS, Mohan HV, Dhama K, Kumar A. Prevalence of Arcobacter spp. in humans, animals and foods of animal origin including sea food from India. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2011;58(5):402–10.

Vandenberg O, Dediste A, Houf K, Ibekwem S, Souayah H, Cadranel S, et al. Arcobacter species in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(10):1863–7.

Fallas-Padilla KL, Rodriguez-Rodriguez CE, Fernandez Jaramillo H, Arias Echandi ML. Arcobacter: comparison of isolation methods, diversity, and potential pathogenic factors in commercially retailed chicken breast meat from Costa Rica. J Food Prot. 2014;77(6):880–4.

Kim NH, Park SM, Kim HW, Cho TJ, Kim SH, Choi C, et al. Prevalence of pathogenic Arcobacter species in South Korea: comparison of two protocols for isolating the bacteria from foods and examination of nine putative virulence genes. Food Microbiol. 2019;78:18–24.

Merga JY, Leatherbarrow AJ, Winstanley C, Bennett M, Hart CA, Miller WG, et al. Comparison of Arcobacter isolation methods, and diversity of Arcobacter spp. in Cheshire, United Kingdom. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(5):1646–50.

Scullion R, Harrington CS, Madden RH. A comparison of three methods for the isolation of Arcobacter spp. from retail raw poultry in Northern Ireland. J Food Prot. 2004;67(4):799–804.

Jansen A, Stark K, Kunkel J, Schreier E, Ignatius R, Liesenfeld O, et al. Aetiology of community-acquired, acute gastroenteritis in hospitalised adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:143.

Son I, Englen MD, Berrang ME, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Harrison MA. Antimicrobial resistance of Arcobacter and Campylobacter from broiler carcasses. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2007;29(4):451–5.

Vandenberg O, Houf K, Douat N, Vlaes L, Retore P, Butzler JP, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of non-jejuni/coli campylobacters and arcobacters from Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57(5):908–13.

EUCAST. (2019). “European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Data from the EUCAST MIC distribution website.” Retrieved 12 Aug, 2019, from http://www.eucast.org.

Riesenberg A, Fromke C, Stingl K, Fessler AT, Golz G, Glocker EO, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri: development and application of a new protocol for broth microdilution. J Antimicrob Chemoth. 2017;72(10):2769–74.

Van den Abeele AM, Vogelaers D, Vanlaere E, Houf K. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus strains isolated from Belgian patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(5):1241–4.

Rahimi E. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Arcobacter species isolated from poultry meat in Iran. Br Poult Sci. 2014;55(2):174–80.

Fanelli F, Di Pinto A, Mottola A, Mule G, Chieffi D, Baruzzi F, et al. Genomic characterization of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from shellfish: novel insight into antibiotic resistance and virulence determinants. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:670.

Zacharow I, Bystron J, Walecka-Zacharska E, Podkowik M, Bania J. Genetic diversity and incidence of virulence-associated genes of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus isolates from pork, beef, and chicken meat in Poland. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:956507.

Zhao S, Tyson GH, Chen Y, Li C, Mukherjee S, Young S, et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis accurately predicts antimicrobial resistance phenotypes in Campylobacter spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(2):459–66.

Sproston EL, Wimalarathna HML, Sheppard SK. Trends in fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter. Microbial Genomics. 2018;4(8):e000198.

Wagner J, Jabbusch M, Eisenblatter M, Hahn H, Wendt C, Ignatius R. Susceptibilities of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from Germany to ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and tetracycline. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(7):2358–61.

Vicente-Martins S, Oleastro M, Domingues FC, Ferreira S. Arcobacter spp. at retail food from Portugal: prevalence, genotyping and antibiotics resistance. Food Control. 2018;85:107–12.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Funding

This work was supported from the German Federal Ministries of Education and Research (BMBF) by Grant 01Kl1712 (Arco-Path). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VB performed experiments, analyzed data, wrote paper, UF performed experiments, analyzed data, co-edited paper, RI provided advice in study design, critically discussed results, co-edited paper, JF provided advice in study design, critically discussed results, co-edited paper, ME provided advice in study design, critically discussed results, co-edited paper, MH provided advice in study design, critically discussed results, co-edited paper, TA provided advice in study design, critically discussed results, co-edited paper, SB provided advice in study design, critically discussed results, co-edited paper, GG designed study, performed experiments, analyzed data, co-wrote paper, MMH designed study, co-wrote paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union. All stool samples were routinely submitted for isolation and identification of bacterial enteropathogens, and no examinations were performed other than requested. All samples were pseudonymized before performance of the Arcobacter-specific isolation procedures. Therefore no informed consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Brückner, V., Fiebiger, U., Ignatius, R. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Arcobacter species in human stool samples derived from out- and inpatients: the prospective German Arcobacter prevalence study Arcopath. Gut Pathog 12, 21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-020-00360-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-020-00360-x