Abstract

Background

Campylobacter species are the major food-borne pathogens which could cause bacterial gastroenteritis in humans. Contaminated chicken products have been recognized as the primary vehicles of Campylobacter transmission to human beings. In this study, the prevalence of Campylobacter in retail chicken meat in Central China was investigated, and the isolates were further characterized using molecular approaches and tested for antibiotic resistance.

Results

A total of 302 chicken samples purchased from April 2014 to April 2015 were tested. The level of Campylobacter contamination was enumerated by most probable number-PCR (MPN-PCR). The Campylobacter positive rate was 17.2% (52/302), with bacterial count varying from 3.6 to 360 MPN/g in positive samples. A total of 52 Campylobacter strains, including 40 Campylobacter jejuni and 12 Campylobacter coli, were isolated from the positive samples. To examine the genetic diversity of the isolates, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) technology was applied, which identified 23 sequence types (STs) belonging to seven clonal complexes (CCs) and unassigned. Among them, the dominant CCs of C. jejuni included CC-353 and CC-464, and the dominant CCs of C. coli were CC-828 and CC-1150. Antibiotic resistance analysis showed that all of the isolates were resistant to norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin. 23 virulence-associated genes were tested in the isolates, which showed that the number of virulence-associated genes detected in the C. jejuni isolates ranged from 16 to 21, while in most of the C. coli isolates ranged from 12 to 16. Virulence-associated genes, flaA, flgB, flgE2, fliM, fliY and cadF were detected in all isolates. VirB11, however, was not detected in any of the isolates.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the contamination level and molecular biological features of Campylobacter strains in retail chicken meat in Central China, which showed high genetic diversity and remarkable antibiotic resistance. This study provided scientific data for the risk assessment and evaluation of Campylobacter contamination in retail chicken products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thermophilic Campylobacter is the major food-borne pathogen that cause human bacterial gastroenteritis in both developed and developing countries [1]. Every year, approximately 1% of the human population in Europe are infected with Campylobacter [2], and the infection rate in the United States is equally high [3]. In North China in 2007, 36 cases of Guillain–Barre syndrome, which was triggered by Campylobacter jejuni infection, have been reported [4]. In addition, due to the prophylactic or therapeutic application of antimicrobials in animal husbandry, Campylobacter isolates have raised great concerns because of the spreading of the fluoroquinolone, erythromycin, and/or other drug-resistant strains [5], which limits treatment alternatives.

Campylobacter, mainly include C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli, are widely colonized in the intestinal tract of wild and domesticated animals and birds [6–8], even in water [9]. Chicken is one of the most popular animal-based foods worldwide, but is also an important reservoir of Campylobacter. The contaminated chicken products are recognized as the main source of infection [10], which highlights its potential public health threat. Several epidemiologic studies on Campylobacter have been carried out in parts of China. From 2008 to 2014, Wang et al. isolated large amounts of Campylobacter in chicken in five provinces of China, with positive rate of 18.1% for C. jejuni and 19.0% for C. coli [11]. Zhang et al. analyzed the genetic diversity of the C. jejuni isolates in Eastern China by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and defined 94 sequence types (STs) belonging to 18 clonal complexes (CCs) [12]. To my best knowledge, few data were reported on the prevalence and contamination level of Campylobacter in chicken products in Central China, so the risk assessments related to food safety are also hampered by the lack of basic data.

At the same time, a number of putative virulence and toxin genes have been identified using the molecular biology methods. However, virulence mechanisms in campylobacteriosis are not fully understood. Bacterial flagellum is one of the most important virulence factors, which is associated with motility, adhesion and invasion. Konkel et al. showed that flagellar mutants had significantly reduced invasion ability [13–15]. CheY is a response regulator needed for flagellar rotation [16]. CiaB is a Campylobacter-invasive antigen, which is secreted through the flagellar export apparatus [13]. Some other adhesion-associated proteins have also been identified, including CadF and PEB1 [17, 18]. Several toxins were also identified in Campylobacter, among them, cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), composed of three subunits, has been found to be lethal for host enterocytes [19]. In addition, virB11 gene encoded in a plasmid is a marker potentially associated with the virulence of Campylobacter species [20].

Retail broiler chicken meat is the last part of a broiler production chain. Therefore, the prevalence of Campylobacter in retail chicken meat is a clear reflection of consumer exposure. In this study, the prevalence of Campylobacter in retail chicken meat in Central China was investigated, and then the Campylobacter strains were isolated and characterized to assess their genetic relation, potential virulence factors and antibiotic resistance profiles.

Methods

Sampling and MPN-PCR analysis

A total of 302 samples including frozen chicken meat (n = 130) and fresh chicken meat (n = 172) were purchased from 20 supermarkets and wet markets every 3 months from April 2014 to April 2015. Each sample was homogenized, and the number of Campylobacter in 10 g sample homogenate was enumerated using a three-tube MPN combining with PCR method [21]. In brief, a ten-fold serial dilution series of each homogenates were prepared. Then 1 ml of each original homogenate or the diluted homogenate was transferred into each of the three tubes containing 9 ml of Bolton Enrichment Broth (OXOID, Basingstoke, England) and incubated at 42 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic condition. After incubation, total bacterial DNA was extracted and PCR amplification of 16s rDNA was performed to detect Campylobacter positive tubes. For statistical analysis, the differences in frequencies were analyzed by Chi square test.

Isolation of Campylobacter

Campylobacter strains were isolated from the positive samples and further confirmed by PCR test as previously described [22]. Isolation of the strains was performed in accordance with the International Standards Organization [ISO] 10272-1 (2006) guidelines [23].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Campylobacter isolates were tested for susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs using a disk diffusion assay as described previously [24], with modifications. In brief, subcultures of isolates were resuspended in Mueller–Hinton broth (OXOID, Basingstoke, UK) to obtain a turbidity equivalent to a 1.0 McFarland standard, and the suspensions were spread onto Mueller–Hinton II agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood. The disks containing each antibiotic were placed on the surfaces of the inoculated Mueller–Hinton II agar plates. These antimicrobial disks (OXOID, Basingstoke, UK) included ampicillin (Amp 10 μg), cefoperazone (Cef 75 μg), streptomycin (Str 10 μg), amikacin (Ami 30 μg), tetracycline (Tet 10 μg), sulfamethoxazole (Sul 300 μg), ciprofloxacin (Cip 5 μg), norfloxacin (Nor 10 μg), clindamycin (Cli 10 μg) and erythromycin (Ery 10 μg). Inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h in a microaerobic environment. Diameters of the inhibition zone were measured and interpreted following the disk manufacturer’s instructions and compared against the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute standard guidelines for aerobic gram-negative bacilli to interpret the results as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant. E. coli ATCC 25922 strain was included in the test for quality control.

MLST analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using MiniBEST Universal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Seven housekeeping genes, aspA, glnA, gltA, glyA, pgm, tkt and uncA, were amplified and sequenced based on the MLST protocol described by Dingle et al. [25]. The obtained sequences were analyzed using Campylobacter MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter), and the allele numbers, sequence types (STs) and clonal complexes (CCs) were assigned. Based on the seven housekeeping gene sequences, consensus tree was constructed by using the UPGMA cluster analysis.

Detection of virulence-associated genes

Twenty three virulence-associated genes were detected by PCR tests. The primers and amplification conditions were used as previously described [26, 27]. PCR was performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). The PCR products were subject to agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA bands were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized using a GelDoc XR System (Bio-Rad, Shanghai, China).

Results

Contamination of Campylobacter in chicken meat

The presence of Campylobacter in the chicken meat was shown in Table 1. A total of 52 Campylobacter positives were found in the 302 collected samples of chicken meat and the contamination rate of Campylobacter was 17.2% in all tested samples. Hereinto, the Campylobacter positive rate in fresh chicken meat (22.1%) was higher than in frozen chicken meat (10.8%) in our study (p < 0.01). On average, 45.1 MPN/g of Campylobacter was detected in the positive samples, and no significant difference in contamination level was found between fresh and frozen chicken meat samples (p = 0.208). Campylobacter strains were isolated from the positive samples and species were further identified by biochemical identification and PCR tests as previously described [22]. A total of 52 Campylobacter strains were isolated, including 40 C. jejuni and 12 C. coli.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

As show in Fig. 1, all the C. jejuni and C. coli isolates were resistant to norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin (100% in C. jejuni and C. coli), followed by resistance to tetracycline (90% in C. jejuni and 83.3% in C. coli) and ampicillin (82.5% in C. jejuni and 100% in C. coli). Only four C. jejuni (10%) and two C. coli (16.7%) isolates were resistant to amikacin, showing the lowest resistance rate (11.5% in total) in this study. In total, 24 antimicrobial resistance profiles were identified among 52 Campylobacter isolates, and all the isolates were resistant to at least three tested antimicrobial agents (Table 2). The most frequent multidrug resistance pattern was resistant to tetracycline, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin. Four isolates showed resistance to nine of ten tested antimicrobial agents. The results of drug resistance test have been showed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

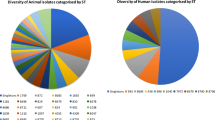

Diversity of Campylobacter MLST genotype

As shown in Table 3, 52 isolates contained a total of 23 different STs belonging to seven CCs and unassigned. Three STs including 15 isolates belonged to CC-464, accounting for 28.8% (15/52) of all isolates in this study. Nine strains belonged to ST-464, which is the most identified sequence type. The major clonal complexes also include CC-353 and CC-1150. All identified STs were further analyzed using the UPGMA cluster analysis (Fig. 2). 23 identified STs were classified into four clonal groups. All of the C. jejuni isolates belonged to Group 1 and 2, and all of the C. coli isolates belonged to Group 3 and 4. Group 1 had the largest number of STs, containing 37 strains belonging to 14 different STs (total of 71.2% isolates). Group 2, Group 3 and Group 4 included 2 STs belonging to CC-21, 4 STs belonging to CC-1150 and 3 STs belonging to CC-828 respectively.

Distribution of virulence-associated genes

A total of 23 virulence-associated genes were screened by PCR in this study (Table 3). FlaA, flgB, flgE2, fliM, fliY and cadF were detected in all Campylobacter isolates, while virB11 was not detected in any isolates. Various detection rates were observed for the rest of the virulence-associated genes. Among them, flaB (51/52, 98.1%), cdtA (51/52, 98.1%), cdtB (50/52, 96.2%), cdtC (50/52, 96.2%), ilpA (51/52, 98.1%), cheY (49/52, 94.2%) and flhA (49/52, 94.2%) were found in more than 90% isolated strains. In contrast, wlaN (7.7%, 4/52) and cgtB (7.7%, 4/52) were only detected in four strains, respectively. Strains with all tested virulence genes were not evenly distributed among C. jejuni and C. coli isolates (Fig. 3). The number of virulence-associated genes detected in C. jejuni (in Group 1 and Group 2) ranged from 16 to 21. Two strains belonged to CC-21 contained the most virulence-associated genes (n = 21). In contrast, less virulence-associated genes, ranging from 12 to 16, were detected in most of the C. coli isolates (in Group 3 and Group 4), except one strain belonging to CC-828 contained 18. Two strains with the fewest virulence-associated genes (n = 12) were in CC-1150 and CC-828 respectively.

Discussion

Chicken and their products are commonly consumed by human, but little detailed information is available about Campylobacter from retail chicken meat in China. In this study, we found that 17.2% of the retail chicken meat samples were contaminated with Campylobacter and the contamination levels ranged from 3.6 to 360 MPN/g in positive samples in Central China. Furthermore, the major MLST genotypes of Campylobacter were CC-353, CC-464 and CC-1150, meanwhile all the isolates were fluoroquinolone-resistant. To my best known, this is the first surveillance report of Campylobacter enumeration study of retail chicken meat in Central China.

Wong et al. study showed that the prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli was as high as 89.1% in chicken meat with a total bacterial count varying from 0 to 110 MPN/g in New Zealand [28]. In Beijing, China, 26.3% of the retail whole chicken carcasses were contaminated by Campylobacter [29]. Our data showed that, the contamination rate of Campylobacter was lower than some of the developed countries. The relatively low positive rate of Campylobacter was also reported in East China [30]. A risk assessment revealed that in an outbreak of C. jejuni infection, the infection rate and ingestion dose were 37.5% and 360 MPN [31]. In our study, the numbers of contaminated bacteria in 65.4% (34/52) of Campylobacter positive samples were more than 10 MPN/g, in other words, more than 104 MPN/kg. The high contamination levels of Campylobacter suggested that the buyers should take care of the food processing process [32].

It is reported that antibiotics resistant strains of Campylobacter lead to more severe disease in humans [33]. High resistance rates were observed in our study. It is certain that the severe multi-drug resistance increases the threat to public safety. Fluoroquinolones and tetracycline are used as therapeutic drugs in severe cases of infection frequently [34]. However, all of the isolates were fluoroquinolone-resistance, while the tetracycline-resistance reached 88.5%. High fluoroquinolone and tetracycline-resistance rates were also reported in other studies in China and other countries [27, 29]. In contrast, in countries with strict antimicrobial controls, much lower resistance rates of ciprofloxacin were observed in Campylobacter [35, 36]. Erythromycin is the preferred drug for treatment of human campylobacteriosis in lots of countries [34]. The resistance rate to erythromycin was 19.2%, which was lower than most of the tested drugs in our study. Lower resistance rate to erythromycin was also reported in other countries [27, 36]. In our study, most of the isolates (82.7%) were sensitive to amikacin and streptomycin, and similar results were reported in several previous studies [37, 38].

Our study revealed a high diversity of genotypes among 52 Campylobacter isolates obtained from the supermarkets and wet markets in Central China, including CC-353, CC-464, CC-1150 and so on. It is noteworthy that all of the unassigned STs are clustering in Group one and most of them are clustering with CC-353 or CC-464, which suggesting their close genetic relationship with the dominant clonal complexes in Central China. CC-353 and CC-354 are also the most frequently reported C. jejuni genotypes in human disease, such as in Greece and Scotland [39, 40]. In retail chicken carcasses in Beijing, North China, the dominant clonal complexes of C. coli were CC-828 and CC-1150, which were the same as in our study, but the clonal complexes of C. jejuni were diverse [29]. In Zeng’s study, ST-21 was the major type in East China, accounting for 39.3% of the total strains [30]. In our study, however, only two C. jejuni strains belonging to ST-21 were isolated. These results suggested that the dominant clonal complexes of C. jejuni were discrepant in different regions of China, but the dominant clonal complexes of C. coli were similar. In our previous epizootic investigation of some chicken farm in Central China, we found that the positive rate of Campylobacter in cloacal swabs was 15.8%. Within seven observed CCs in this study, six CCs except CC-48 were also observed (unpublished), which revealed the high similarity between isolates from farms and markets. Initial meat contamination with Campylobacter may come from the destructive chicken intestine during processing [41]. This study provided supporting evidence and further indicated the importance of good biosecurity during the manufacturing process, especially for ensuring the integrity of intestine. Otherwise, in order to reduce Campylobacter contamination in chicken meat, we think the most important thing is to lower the bacterial count in chickens. Incorporating antibiotics into feed might help reduce the levels of colonization, but will produce resistant strains. Rational use of environment-friendly microbial feed additive seems to be a good way.

Potential virulence properties include motility, chemotaxis, colonization, adhesion and invasion of epithelial cell, intracellular survival, and formation of toxins. To understand better the virulence potential of our isolates, we characterized 23 virulence-associated genes in these processes [26, 42]. Flagellar is one of the most important factors associated with adhesion, invasion and colonization. High detection rates of flagellar genes were observed in both C. jejuni and C. coli. Among them, five genes (flaA, flgB, flgE2, fliM and fliY) were detected in all tested strains and another three (flaB, flhA and flhB) were detected in more than 88% of the strains. High detection rates of flagellar genes have been also reported in other studies [26, 43], except flab which was absent in 8 of 17 tested C. jejuni in Koolman’ study [44]. In contrast, flaB was only absent in one of our tested C. jejuni strains (1/40). A fibronectin-binding protein encoded by cadF was another virulence factor detected in all strains. wlaN and cgtB genes were detected in a few strains, in which their detection rates were both 7.7% (4/52). The low detection rate of these two genes may because that they are not essential for colonization and pathogenesis of Campylobacter. virB11 is located in the pVir plasmid [45]. We could not detect virB11, indicating that all of our isolates did not have the pVir plasmid.

Few studies reported the distribution of virulence factors in C. coli. As shown in Fig. 3, we found that the distribution of virulence-associated factors in C. jejuni and C. coli were different. The results showed that the number of virulence-associated genes detected in C. jejuni isolates ranged from 16 to 21, while in most of the C. coli isolates, ranging from 12 to 16. Especially for invasion related genes, ciaB and iamA, and chemotaxis factors, docA and docB, the detection rates of these four genes in C. jejuni were much higher than in C. coli (ciaB, 90 vs 16.7%; iamA, 92.5 vs 33.3; docA, 100 vs 16.7%; docB, 100 vs 8.3%). In addition, chemotaxis factors cheY was present in all C. jejuni strains but was absent in 3 of the 12 C. coli strains. Some subunit of cytolethal distending toxins were also absent in a small part of C. coli. As reported, most of campylobacteriosis were caused by C. jejuni [46]. It may because that the prevalent strains of C. jejuni contained more virulence factors than C. coli. In this study, most virulence associated genes were found in two C. jejuni isolates belonging to ST-21. CC-21 shows a large overlap in genetic variation among reservoirs, including both animals (e.g. cattle, sheep, pig, wild bird) and environmental sources, more virulence associated genes may contribute to its adaptation to a variety of environment [47, 48]. Although CC-353 and CC-354 are frequently reported in human disease, the numbers of virulence associated genes were not more than others. We inferred that some of the detected virulence associated genes might not be essential for human infection. We think these results will provide useful information for further understanding the mechanisms of pathogenesis in C. jejuni and C. coli.

Conclusions

This study firstly provided the information about the contamination levels and genetic diversity of Campylobacter in retail chicken meat in Central China. We also showed antibiotic susceptibility profiles and distribution of virulence-associated genes. This study provided a basic data for risk assessment of food-borne transmission of Campylobacter. Further investigations are needed to improve our knowledge about the epidemiology of Campylobacter in human in Central China.

Abbreviations

- MPN:

-

most probable number

- MLST:

-

multilocus sequence typing

- STs:

-

sequence types

- CCs:

-

clonal complexes

References

Coker AO, Isokpehi RD, Thomas BN, Amisu KO, Obi CL. Human campylobacteriosis in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(3):237–44.

Epps SV, Harvey RB, Hume ME, Phillips TD, Anderson RC, Nisbet DJ. Foodborne Campylobacter: infections, metabolism, pathogenesis and reservoirs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(12):6292–304.

Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(5):607–25.

Ye Y, Zhu D, Wang K, Wu J, Feng J, Ma D, Xing Y, Jiang X. Clinical and electrophysiological features of the 2007 Guillain–Barre syndrome epidemic in northeast China. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(3):311–4.

Iovine NM. Resistance mechanisms in Campylobacter jejuni. Virulence. 2013;4(3):230–40.

Blaser MJ, LaForce FM, Wilson NA, Wang WL. Reservoirs for human campylobacteriosis. J Infect Dis. 1980;141(5):665–9.

Keller JI, Shriver WG. Prevalence of three campylobacter species, C. jejuni, C. coli, and C. lari, using multilocus sequence typing in wild birds of the Mid-Atlantic region, USA. J Wildl Dis. 2014;50(1):31–41.

Weis AM, Miller WA, Byrne BA, Chouicha N, Boyce WM, Townsend AK. Prevalence and pathogenic potential of campylobacter isolates from free-living, human-commensal american crows. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(5):1639–44.

Szewzyk U, Szewzyk R, Manz W, Schleifer KH. Microbiological safety of drinking water. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:81–127.

Horrocks SM, Anderson RC, Nisbet DJ, Ricke SC. Incidence and ecology of Campylobacter jejuni and coli in animals. Anaerobe. 2009;15(1–2):18–25.

Wang Y, Dong Y, Deng F, Liu D, Yao H, Zhang Q, Shen J, Liu Z, Gao Y, Wu C, et al. Species shift and multidrug resistance of Campylobacter from chicken and swine, China, 2008–14. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(3):666–9.

Zhang G, Zhang X, Hu Y, Jiao XA, Huang J. Multilocus sequence types of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from different sources in Eastern China. Curr Microbiol. 2015;71(3):341–6.

Konkel ME, Klena JD, Rivera-Amill V, Monteville MR, Biswas D, Raphael B, Mickelson J. Secretion of virulence proteins from Campylobacter jejuni is dependent on a functional flagellar export apparatus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(11):3296–303.

Sommerlad SM, Hendrixson DR. Analysis of the roles of FlgP and FlgQ in flagellar motility of Campylobacter jejuni. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(1):179–86.

Yao R, Burr DH, Doig P, Trust TJ, Niu H, Guerry P. Isolation of motile and non-motile insertional mutants of Campylobacter jejuni: the role of motility in adherence and invasion of eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14(5):883–93.

Yao R, Burr DH, Guerry P. CheY-mediated modulation of Campylobacter jejuni virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23(5):1021–31.

Konkel ME, Garvis SG, Tipton SL, Anderson DE Jr, Cieplak W Jr. Identification and molecular cloning of a gene encoding a fibronectin-binding protein (CadF) from Campylobacter jejuni. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24(5):953–63.

Pei Z, Blaser MJ. PEB1, the major cell-binding factor of Campylobacter jejuni, is a homolog of the binding component in gram-negative nutrient transport systems. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(25):18717–25.

Lee RB, Hassane DC, Cottle DL, Pickett CL. Interactions of Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin subunits CdtA and CdtC with HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71(9):4883–90.

Bacon DJ, Alm RA, Hu L, Hickey TE, Ewing CP, Batchelor RA, Trust TJ, Guerry P. DNA sequence and mutational analyses of the pVir plasmid of Campylobacter jejuni 81–176. Infect Immun. 2002;70(11):6242–50.

Tang JY, Nishibuchi M, Nakaguchi Y, Ghazali FM, Saleha AA, Son R. Transfer of Campylobacter jejuni from raw to cooked chicken via wood and plastic cutting boards. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2011;52(6):581–8.

Kos VN, Gibreel A, Keelan M, Taylor DE. Species identification of erythromycin-resistant Campylobacter isolates and optimization of a duplex PCR for rapid detection. Res Microbiol. 2006;157(6):503–7.

Moran L, Kelly C, Madden RH. Factors affecting the recovery of Campylobacter spp. from retail packs of raw, fresh chicken using ISO 10272-1:2006. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;48(5):628–32.

Serichantalergs O, Pootong P, Dalsgaard A, Bodhidatta L, Guerry P, Tribble DR, Anuras S, Mason CJ. PFGE, Lior serotype, and antimicrobial resistance patterns among Campylobacter jejuni isolated from travelers and US military personnel with acute diarrhea in Thailand, 1998–2003. Gut Pathog. 2010;2(1):15.

Dingle KE, Colles FM, Wareing DR, Ure R, Fox AJ, Bolton FE, Bootsma HJ, Willems RJ, Urwin R, Maiden MC. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(1):14–23.

Muller J, Schulze F, Muller W, Hanel I. PCR detection of virulence-associated genes in Campylobacter jejuni strains with differential ability to invade Caco-2 cells and to colonize the chick gut. Vet Microbiol. 2006;113(1–2):123–9.

Nguyen TN, Hotzel H, El-Adawy H, Tran HT, Le MT, Tomaso H, Neubauer H, Hafez HM. Genotyping and antibiotic resistance of thermophilic Campylobacter isolated from chicken and pig meat in Vietnam. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:19.

Wong TL, Hollis L, Cornelius A, Nicol C, Cook R, Hudson JA. Prevalence, numbers, and subtypes of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in uncooked retail meat samples. J Food Prot. 2007;70(3):566–73.

Bai Y, Cui S, Xu X, Li F. Enumeration and characterization of campylobacter species from retail chicken carcasses in Beijing, China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2014;11(11):861–7.

Zeng D, Zhang X, Xue F, Wang Y, Jiang L, Jiang Y. Phenotypic characters and molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni in East China. J Food Sci. 2016;81(1):M106–13.

Hara-Kudo Y, Takatori K. Contamination level and ingestion dose of foodborne pathogens associated with infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(10):1505–10.

van Asselt ED, de Jong AE, de Jonge R, Nauta MJ. Cross-contamination in the kitchen: estimation of transfer rates for cutting boards, hands and knives. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;105(5):1392–401.

Wieczorek K, Osek J. Antimicrobial resistance mechanisms among Campylobacter. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:340605.

Wirz SE, Overesch G, Kuhnert P, Korczak BM. Genotype and antibiotic resistance analyses of Campylobacter isolates from ceca and carcasses of slaughtered broiler flocks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(19):6377–86.

Zhao S, Young SR, Tong E, Abbott JW, Womack N, Friedman SL, McDermott PF. Antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter isolates from retail meat in the United States between 2002 and 2007. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(24):7949–56.

Miflin JK, Templeton JM, Blackall PJ. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from poultry in the South-East Queensland region. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(4):775–8.

Luber P, Bartelt E, Genschow E, Wagner J, Hahn H. Comparison of broth microdilution, E Test, and agar dilution methods for antibiotic susceptibility testing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(3):1062–8.

Gu W, Siletzky RM, Wright S, Islam M, Kathariou S. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and strain type diversity of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from turkeys in eastern North Carolina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(2):474–82.

Ioannidou V, Ioannidis A, Magiorkinis E, Bagos P, Nicolaou C, Legakis N, Chatzipanagiotou S. Multilocus sequence typing (and phylogenetic analysis) of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli strains isolated from clinical cases in Greece. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:359.

Sheppard SK, Dallas JF, Strachan NJ, MacRae M, McCarthy ND, Wilson DJ, Gormley FJ, Falush D, Ogden ID, Maiden MC, et al. Campylobacter genotyping to determine the source of human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(8):1072–8.

Normand V, Boulianne M, Quessy S. Evidence of cross-contamination by Campylobacter spp. of broiler carcasses using genetic characterization of isolates. Can J Vet Res. 2008;72(5):396–402.

Ketley JM. Pathogenesis of enteric infection by Campylobacter. Microbiology. 1997;143(Pt 1):5–21.

Krutkiewicz A, Klimuszko D. Genotyping and PCR detection of potential virulence genes in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from different sources in Poland. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2010;55(2):167–75.

Koolman L, Whyte P, Burgess C, Bolton D. Distribution of virulence-associated genes in a selection of Campylobacter isolates. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12(5):424–32.

Bacon DJ, Alm RA, Burr DH, Hu L, Kopecko DJ, Ewing CP, Trust TJ, Guerry P. Involvement of a plasmid in virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81–176. Infect Immun. 2000;68(8):4384–90.

Tam CC, O’Brien SJ, Tompkins DS, Bolton FJ, Berry L, Dodds J, Choudhury D, Halstead F, Iturriza-Gomara M, Mather K, et al. Changes in causes of acute gastroenteritis in the United Kingdom over 15 years: microbiologic findings from 2 prospective, population-based studies of infectious intestinal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(9):1275–86.

Manning G, Dowson CG, Bagnall MC, Ahmed IH, West M, Newell DG. Multilocus sequence typing for comparison of veterinary and human isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(11):6370–9.

Ragimbeau C, Schneider F, Losch S, Even J, Mossong J. Multilocus sequence typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and fla short variable region typing of clonal complexes of Campylobacter jejuni strains of human, bovine, and poultry origins in Luxembourg. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(24):7715–22.

Authors’ contributions

TZ, QL and HS participated in the conception and design of the study. TZ, YC, TL, RZ, LL, HW and QL performed the farm and laboratory work. TZ, YC, TL, GW and HS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. TZ, YC, QL, GW, DA and HS contributed to the analysis and helped in the manuscript discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Funding

This work was supported by Chinese Key Research and Development Plan (2016YFD0501305), Chinese Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303044) and China Agriculture Research System (CARS-42-G11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Luo, Q., Chen, Y. et al. Molecular epidemiology, virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spreading in retail chicken meat in Central China. Gut Pathog 8, 48 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-016-0132-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-016-0132-2