Abstract

Background

Gout treatment remains suboptimal. Identifying populations at risk of developing gout may provide opportunities for prevention. Our aim was to assess the risk of incident gout associated with obesity, hypertension and diuretic use.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies in adults (age ≥ 18 years) from primary care or the general population, exposed to obesity, hypertension or diuretic use and with incident gout as their outcome.

Results

A total of 9923 articles were identified: 14 met the inclusion criteria, 11 of which contained data suitable for pooling in the meta-analysis. Four articles were identified for obesity, 10 for hypertension and six for diuretic use, with four, nine and three articles included respectively for each meta-analysis. Gout was 2.24 times more likely to occur in individuals with body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 (adjusted relative risk 2.24 (95% confidence interval) 1.76–2.86). Hypertensive individuals were 1.64 (1.34–2.01) and 2.11 (1.64–2.72) times more likely to develop gout as normotensive individuals (adjusted hazard ratio and relative risk respectively). Diuretic use was associated with almost 2.5 times the risk of developing gout compared to no diuretic use (adjusted relative risk 2.39 (1.57–3.65)).

Conclusions

Obesity, hypertension and diuretic use are risk factors for incident gout, each more than doubling the risk compared to those without these risk factors. Patients with these risk factors should be recognised by clinicians as being at greater risk of developing gout and provided with appropriate management and treatment options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gout affects 2.5% of adults in the UK, with prevalence and incidence continuing to rise [1, 2]. The primary risk factor for gout is an elevated serum urate level (hyperuricaemia), leading to monosodium urate crystal deposition in and around joints, acute attacks of crystal synovitis and progressive joint damage [3]. Long-term treatment of gout involves using urate-lowering therapies (ULT), typically allopurinol [4] to inhibit xanthine oxidase, resulting in improved long-term outcomes. Despite this, treatment use remains suboptimal [5] and, therefore, identifying populations at risk of developing gout, especially those in primary care where the majority of patients with gout are managed, may provide opportunities for primary prevention.

Body mass index (BMI) and hypertension have been identified as risk factors for incident gout in a number of large epidemiological studies [6], yet the magnitude of risk varies between studies. Obesity promotes insulin resistance which in turn reduces renal urate excretion resulting in hyperuricaemia [7]. Hypertension predisposes to gout by reducing renal urate excretion due to glomerular arteriolar damage and glomerulosclerosis. Diuretics are perhaps the most well-known medications to be associated with gout; they raise serum uric acid levels by increasing uric acid reabsorption and decreasing uric acid secretion in the kidneys. However, it has also been proposed that diuretic use alone does not increase the risk of gout and that the observed associated risk is due to the presence of co-morbidities which they are used to treat; commonly hypertension, heart failure and renal failure [8]. Studying obesity, hypertension and diuretic use and their association with incident gout to elucidate the true nature and magnitude is important because all three are common and can be modified. We performed a systematic review of cohort studies with the aim of deriving pooled estimates of the risk of incident gout associated with obesity, hypertension and diuretic use.

Methods

Literature search

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library from their inception to March 2017. A combination of free-text and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, or database-specific equivalents, were used (Appendix 1). Reference lists of included articles were searched for additional eligible articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were developed using the PICOS framework [9]. The population of interest was adults aged 18 years or older. Studies which included participants under the age of 18 years at cohort entry, but in whom outcome was assessed in adulthood, were deemed to meet this inclusion criterion. Articles were required to have examined at least one of: obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), hypertension (self-reported, physician-diagnosed or study-defined mmHg value) or diuretic use (self-reported or reported in records) and their association with incident gout, defined as the first recorded episode (i.e. a subsequent new diagnosis of gout). Articles which studied the incidence of gout in specific hyperuricaemic populations were excluded. Included articles had to be cohort studies, prospective or retrospective and undertaken in primary care or the general population.

No restrictions were imposed on language or the time periods for publication, with medical literature databases searched from inception. Where full articles could not be obtained, these were requested from the corresponding author.

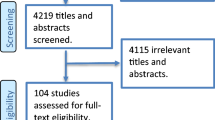

Screening process

After duplicates had been removed from the initial search, the titles and abstracts of all of the remaining articles were screened by two authors (PLE and CH). Two authors (PLE/CH and JAP) then independently reviewed the full text of the remaining articles to decide on inclusion. Any articles where there was disagreement about inclusion were subsequently arbitrated over by a third author (ER).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted from the full set of eligible articles by a single author (PLE/CH) and also extracted independently from a subset (50%) of the eligible articles by a second author (JAP). If risk estimates were not reported in the original articles, these were requested from the corresponding author. Extracted variables included author, year and title of publication, country in which the study took place, the number of years of follow-up, baseline demographics of participants which included age, gender and ethnicity, the number of cases of incident gout, the study setting (primary care or general population), exposure of interest and method of definition used, the method of gout diagnosis and the risk estimate of incident gout associated with that particular exposure, and both unadjusted and adjusted values were extracted if available. The methodological quality of all eligible articles was assessed independently by two authors (PLE/CH and JAP) using the cohort study template of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Funnel plots were produced from the adjusted data points for each meta-analysis to examine the extent of any publication bias.

Statistical analysis

Narrative synthesis was used to summarise the characteristics of studies included in the systematic review. Estimates were pooled for an individual risk factor if there were a minimum of three values which met the criteria; the exposure was measured in a similar manner and used the same risk estimate (e.g. odds ratio (OR), relative risk (RR), hazards ratio (HR)). Firstly, unadjusted or minimal adjusted risk estimates were pooled for each individual risk factor, and then the maximal multivariate-adjusted risk estimates.

Pooled risk estimates were calculated using random-effects meta-analysis. A random-effects model is considered more appropriate for meta-analyses with the potential for substantial heterogeneity. Quantifying the inconsistency across studies was assessed using Cochran Q and I2 statistics. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models were then used to calculate the pooled risk together with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). The meta-analysis was performed using STATA 13.

Results

Search results

The search yielded a total of 9923 articles. Of these 3606 were duplicates and hence removed, leaving 6317 individual publications to be screened by title and abstract. Forty-nine articles could not be excluded by title and abstract and had their full text reviewed. Thirty-five articles were excluded (Appendix 2), 14 articles met the inclusion criteria [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], no additional articles were identified in their reference lists and a final 11 articles contained data suitable for pooling in the meta-analysis [11, 13,14,15,16,17,18, 22,23,24,25] (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included articles

Thirteen of the 14 articles included in the systematic review used general populations, with one from primary care [13] (Table 1). The majority were from the USA, with the remaining four articles from the UK, Singapore [22], Taiwan [18] and Tokelau (South Pacific island) [10]. Sample sizes for the included articles ranged from 923 to 60,181, with the number of incident cases of gout ranging from 43 to 1341. Two studies included only male participants—one using a cohort of male health professionals [14] and the other a sample of male medical students [12]—and one study included an all-female sample from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study [17]. The remaining 11 studies included both men and women, although the sample in one study was predominantly male (91%) [11]. There was a majority of white participants (ranging from 62 to 100%) in the nine articles which reported the ethnic composition of their samples, with the exception of Prior et al. [10] which examined 100% Tokelauan. Two studies included participants who were aged under 18 years at study entry [10, 16], two studies included those in their mid-twenties (university students) [11, 12], seven studies included participants in middle-older age [14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 22, 25], one study included participants in older age [23] and two studies included wide age ranges (18–89 years) [13, 21]. The length of follow-up of participants ranged from 8 to 52 years.

From the 14 articles included in this review, 11 were used within the meta-analysis. Seven articles were pooled as each had recorded a risk estimate for at least one of the risk factors of interest using RR (95% CI) and four articles were pooled based on their use of HRs (95% CI). The risk estimates from the remaining three articles were not sufficient to pool risk estimates (Table 2).

The covariates which each article included in its maximal adjustment model are described in detail in Table 2; however, the majority of articles adjusted for age, gender, co-morbidities, alcohol intake and food/energy intake. Several adjustment models included specific covariates; however, each of the three risk factors of interest was typically adjusted for both of the other two risk factors. Therefore, of the four obesity articles, all adjusted for hypertension and three adjusted for diuretic use; of the six hypertension articles, five adjusted for BMI and two adjusted for diuretic use; and finally, all three of the articles examining diuretic use as a risk factor for gout adjusted for hypertension and BMI.

Quality appraisal of articles included in the meta-analysis

Three of the 11 studies (27%) included a specific sample (male healthcare professionals (n = 1), medical students (n = 2)) [11, 12, 14]. Six articles (55%) ascertained exposure using a secure record or structured interview, ranking as the highest quality approach [11, 13, 15, 17, 22, 23]. Eight articles (73%) specifically mentioned that they had excluded participants with prevalent gout at the beginning of the study [14,15,16,17,18, 22, 23, 25]. No studies required the diagnosis of gout to be crystal proven, two studies (18%) defined gout through clinical diagnosis [13, 15] and, although the remaining nine studies had defined a new gout diagnosis through self-report, four of these additionally used the ACR criteria [14] or a review of the medical records [11, 12, 22] to support the definition. Three articles (27%) provided unadjusted risk estimates only [11, 13, 23], with the remaining articles providing results with adjustment for at least two confounding factors. Eight articles (73%) provided a description of those lost to follow-up [11, 12, 14,15,16,17, 22, 23] (Appendix 3). Funnel plots for each meta-analysis did not demonstrate any discernible asymmetry (Appendix 4).

Obesity

For obesity, four articles met the inclusion criteria, all of which were suitable for pooling as all had defined obesity as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and provided the RR for incident gout. All articles conducted multivariate analysis; two risk estimates were included from the article by Bhole et al. [15] which reported RRs separately for men and women.

The pooled unadjusted/age-adjusted RR of incident gout in obese individuals compared with non-obese individuals was 2.84 (95% CI 2.15–3.76). The corresponding pooled multivariate-adjusted RR was 2.24 (1.76–2.86). There was no evidence of any statistically significant heterogeneity between the risk estimates as reflected by the low I2 values and non-significant p value (I2 = 21.4%, p = 0.278) (Fig. 2).

Hypertension

For hypertension, 10 articles met the inclusion criteria; of these, five provided RRs and four provided HRs which were suitable for pooling. For the RR meta-analysis, all five articles provided unadjusted/age-adjusted RRs, but only three articles provided multivariate-adjusted RRs. The pooled unadjusted/age-adjusted RR for incident gout in hypertensive individuals was almost three times higher than that in normotensive individuals (RR 2.98 (95% CI 2.63–3.37)). On pooling multivariate RRs, this risk was reduced, but remained significant (2.11 (1.64–2.72)). There was no evidence of any statistically significant heterogeneity between the risk estimates (I2 = 48.3%, p = 0.122) (Fig. 3). For the HR meta-analysis, three articles provided unadjusted/age-adjusted HRs [18, 23, 25] and three provided multivariate-adjusted HRs [18, 22, 25]. The pooled unadjusted/age-adjusted HR for incident gout in hypertensive individuals was almost two times higher than that in normotensive individuals (RR 1.93 (95% CI 1.52–2.46)). On pooling multivariate HRs, this risk was reduced, but remained significant (1.64 (1.34–2.01)). However, heterogeneity was reported as statistically significant (I2 = 78.6%, p = 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Diuretic use

Three of the six articles which met the inclusion criteria for diuretic use were suitable for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Only two studies provided multivariate-adjusted RRs suitable for pooling; however, these studies provided three relevant adjusted risk estimates. The pooled unadjusted/age-adjusted RR of incident gout in people taking diuretics compared to those not taking diuretics was 3.59 (95% CI 3.06–4.21). The corresponding pooled adjusted RR was 2.39 (1.57–3.65). Evidence for statistically significant heterogeneity was identified for the pooled multivariate-adjusted RRs (I2 = 79.1%, p = 0.008), but not for the unadjusted/age-adjusted RRs (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.397) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies has shown that in primary care and general populations, obesity, hypertension and diuretic use are all independent risk factors for incident gout. Each of these more than doubled the risk of developing gout.

Although this is the first meta-analysis of hypertension as a risk factor for gout, our findings for the other risk factors of obesity and diuretic use are supported by previous reviews. Our findings concerning obesity are consistent with those of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis which found that increasing BMI was a risk factor for the development of gout [26]. However, in contrast to our research, this meta-analysis included case–control studies as well as cohort studies, and included some studies of populations with hyperuricaemia, who are at greater risk of gout than the general population, perhaps explaining higher relative risks than those seen in our study. Hueskes et al. [8] published a systematic review examining the risk of gout associated with diuretics. They concluded that there was a trend that patients using either loop or thiazide diuretics were at an increased risk of gout; however, they reported that the magnitude and independence of this association in different studies was inconsistent and that evidence to support stopping diuretics in those with gout was lacking [8]. An important consideration is that their outcome was specifically defined as ‘acute gouty arthritis’ or ‘chronic tophaceous gout’, which is in contrast to the more inclusive outcome used in this study which was incident gout. This previous study did not attempt to pool risk estimates from different studies and was therefore unable to quantify the risk incurred by diuretic use. This systematic review also included randomised controlled trials, cohort studies and case–control studies, whereas our review included only cohort studies.

We have shown that obesity, hypertension and diuretic use are all important risk factors for incident gout. The prevalence of obesity is rising within the UK as well as globally and it has been linked to co-morbidities and mortality; as a result, the obesity epidemic has become a major public health concern. Previous research has demonstrated the benefits of weight reduction interventions in preventing gout [27] and our study has added further evidence to the need to tackle obesity due to its strong association with gout. Hypertension is primarily managed in primary care; careful selection of therapeutic agents can help to reduce the risk of future gout. This study also suggests that diuretics should be avoided in those at risk of developing gout, where possible, and alternatives considered.

Our study had a number of strengths including the comprehensive search strategy and literature review process, with no restrictions on language. By considering only primary care and population-based cohort studies for inclusion, we ensured that the results would be generalisable to most patients with gout, who are managed exclusively in primary care. We only included cohort studies in our review, reducing the effect of recall bias frequently encountered in case–control studies and allowing certainty of any temporal relationships between exposure and outcome [28]. Finally, as the risk estimates included in the meta-analyses were adjusted for the other risk factors of interest (i.e. obesity estimates were adjusted for hypertension, hypertension estimates were adjusted for diuretic use, etc.), we are confident these risk estimates are independent. As a result, it appears that hypertension is a risk factor for gout independent of diuretic use, but none of the included studies adjusted for other anti-hypertensive drugs which can cause hyperuricaemia. Therefore, we were unable to investigate whether the effect of hypertension was also independent of these.

Limitations in our work include that some studies had used specific samples (e.g. health professionals, university students), meaning their sampling frames with lower social deprivation are likely to underestimate the risk of incident gout. Other limitations include, firstly, that one-quarter of the articles did not specifically indicate that they had excluded individuals with a previous diagnosis of gout and, secondly, that variation may exist between pooled multivariate relative risks due to adjustments for different factors within different studies. However, regarding this latter point, several factors were the same (e.g. age, gender) and the majority of articles adjusted for the most important factors (in the case of this review, BMI, hypertension and/or diuretic use). In relation to this, although we are confident on the role of risk for each of these three variables, we are unable to address risk through different interactions of these, which would be clinically useful. Finally, diagnosis of gout was predominantly determined through self-report as no study required gout to be defined using the gold standard of crystal visualisation in the synovial fluid. This raises the possibility of misclassification; however, this approach is not unusual in large population/primary care-based epidemiological studies.

Conclusion

Obesity, hypertension and diuretic use are all risk factors for incident gout, independent of one another and each more than doubling the risk of developing gout compared with those without these conditions. Such patients should be recognised by clinicians as being at greater risk of developing gout and provided with appropriate management and treatment options. Future research into interactions between these individual risk factors would expand our understanding of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of gout. As diuretic use in hypertensive patients is likely and a large proportion of such patients will be overweight, future research should consist of prospective studies which consider the interaction between co-morbidities and examine how certain clusters of co-morbidities influence the risk of developing gout, building on the work of Richette et al. [29].

Abbreviations

- ARIC:

-

Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- ULT:

-

Urate lowering therapies

References

Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1301–11.

Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, Gerster J, Jacobs J, Leeb B, Lioté F, McCarthy G, Netter P, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pignone A, Pimentão J, Punzi L, Roddy E, Uhlig T, Zimmermann-Gòrska I. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1312–24.

Roddy E, Mallen CD, Doherty M. Gout. BMJ. 2013;347:f5648.

Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, Zhang W, Doherty M, Seckl J, Hingorani A, Jaques R, Nuki G, British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group (SGAWG). British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1372–4.

Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, Zhang W, Doherty M. Eligibility for and prescription of urate-lowering treatment in patients with incident gout in England. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2684–6.

Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2014;40(2):155–75.

Ter Maaten JC, Voorburg A, Heine RJ, Ter Wee PM, Donker AJ, Gans RO. Renal handling of urate and sodium during acute physiological hyperinsulinaemia in healthy subjects. Clin Sci (Lond). 1997;92(1):51–8.

Hueskes BAA, Roovers EA, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Janssens HJEM, van de Lisdonk EH, Janssen M. Use of diuretics and the risk of gouty arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(6):879–89.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Prior IA, Welby TJ, Ostbye T, Salmond CE, Stokes YM. Migration and gout: the Tokelau Island migrant study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295(6596):457–61.

Roubenoff R, Klag MJ, Mead LA, Liang KY, Seidler AJ, Hochberg MC. Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men. JAMA. 1991;266(21):3004–7.

Hochberg MC, Thomas J, Johniene Thomas D, Mead L, Levine DM, Klag MJ. Racial differences in the incidence of gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(5):628–32.

Grodzicki T, Palmer A, Bulpitt CJ. Incidence of diabetes and gout in hypertensive patients during 8 years of follow-up. The General Practice Hypertension Study Group. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11(9):583–5.

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):742–8.

Bhole V, de Vera M, Rahman MM, Krishnan E, Choi H. Epidemiology of gout in women: fifty-two-year followup of a prospective cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1069–76.

McAdams DeMarco MA, Maynard JW, Huizinga MM, Baer AN, Köttgen A, Gelber AC, Coresh J. Obesity and younger age at gout onset in a community-based cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(8):1108–14.

Maynard JW, McAdams DeMarco MA, Baer AN, Köttgen A, Folsom AR, Coresh J, Gelber AC. Incident gout in women and association with obesity in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Med. 2012;125(7):717. e9–717.e17.

Chen JH, Yeh WT, Chuang SY, Wu YY, Pan WH. Gender-specific risk factors for incident gout: a prospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(2):239–45.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Maynard JW, Baer AN, Coresh J. Hypertension and the risk of incident gout in a population-based study: the atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(10):675–9.

McAdams DeMarco MA, Maynard JW, Baer AN, Gelber AC, Young JH, Alonso A, Coresh J. Diuretic use, increased serum urate levels, and risk of incident gout in a population-based study of adults with hypertension: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(1):121–9.

Wilson L, Nair KV, Saseen JJ. Comparison of new-onset gout in adults prescribed chlorthalidone vs hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2014;16(12):864–8.

Pan A, Teng GG, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Bidirectional association between self-reported hypertension and gout: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141749.

Burke BT, Kottgen A, Law A, Grams M, Baer AN, Coresh J, McAdams-DeMarco MA. Gout in older adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(4):536–42.

Hochberg MC, Kasper J, Williamson J, Skinner A, Fried LP. The contribution of osteoarthritis to disability: preliminary data from the Women's Health and Aging Study. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1995;43:16–8.

McAdams-Demarco MA, Maynard JW, Baer AN, Coresh J. Hypertension and the risk of incident gout in a population-based study: the atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(10):675–9.

Aune D, Norat T, Vatten LJ. Body mass index and the risk of gout: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(8):1591–601.

Maglio C, Peltonen M, Neovius M, Jacobson P, Jacobsson L, Rudin A, Carlsson LM. Effects of bariatric surgery on gout incidence in the Swedish Obese Subjects study: a non-randomised, prospective, controlled intervention trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;76(4):688–93.

Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(1):54–60.

Richette P, Clerson P, Périssin L, Flipo R, Bardin T. Revisiting comorbidities in gout: a cluster analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):142–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Research Institute for Primary Care and Health Sciences, Keele University for support.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship awarded to CDM (Grant number NIHR-RP-2014-04-026). CDM is also supported by the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands and the NIHR School for Primary Care Research. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

The study sponsors had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR (UK). This article presents independent research which is part-funded by the CLAHRC West Midlands. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAP, CDM and ER are guarantors of overall study integrity. JAP, JB, CDM and ER contributed to study concept and design. PLE, JAP, JB, CDM, CAH and ER contributed to data collection and interpretation. PLE, JAP and JB contributed to statistical analysis. PLE, JAP, JB, CDM, CAH and ER contributed to manuscript preparation. PLE, JAP, JB, CDM, CAH and ER gave final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, P.L., Prior, J.A., Belcher, J. et al. Obesity, hypertension and diuretic use as risk factors for incident gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Arthritis Res Ther 20, 136 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1612-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1612-1