Abstract

Background

Gout is associated with higher cardiovascular risk that increases with disease severity. The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between the extent of monosodium urate (MSU) crystal deposition, assessed with ultrasonography (US) and dual-energy computed tomography (DECT), and cardiovascular risk.

Methods

Gout patients were included in this cross-sectional study to undergo DECT scans for the assessment of total MSU volume deposition in the knees and feet, and US to evaluate the number of joints with the double contour (DC) sign. Participants were screened for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and levels of the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) 10-year risk for heart disease or stroke were calculated. The primary endpoint was the Spearman correlation coefficient ρ between DECT MSU volume and cardiovascular risk.

Results

A total of 42 patients were included; they were predominantly male (40/42) and aged 63.0 ± 13.2 years. Overall, 28/42 patients presented with the metabolic syndrome and the average 10-year coronary event or stroke risk according to the ACC/AHA (n = 33) was 21 ± 15%. Correlations between DECT volumes of MSU deposits in the knees, feet, and knees + feet and cardiovascular risk according to the ACC/AHA were very poor, with ρ = 0.18, −0.01, and 0.13, respectively. The was no correlation between the number of joints with the DC sign and cardiovascular risk (ρ = −0.07). DECT MSU deposit volume was similar in patients with and without metabolic syndrome (p = 0.29).

Conclusions

The extent of MSU burden does not increase the estimated risk of cardiovascular events in gout patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gout is the result of an inflammatory response to monosodium urate (MSU) crystal deposition following prolonged hyperuricemia [1]. The association of gout with increased cardiovascular risk is now fully recognized, but mechanisms linking the two remain unclear [2,3,4]. Cardiovascular risk in gout seems to increase with disease severity, the presence of clinical tophi, and serum urate (SU) levels [5]. It has been hypothesized that a greater urate load could explain this increased cardiovascular mortality [5]. Systematic evaluation of the cardiovascular risk of gout patients at the time of the diagnosis revealed that a majority of patients are classified as having a high cardiovascular risk [6]. In non-gout patients, SU levels may be associated with higher cardiovascular risk scores but causality of hyperuricemia on cardiovascular comorbidities and events, and the metabolic syndrome, remains uncertain [3, 7]. Furthermore, the association between MSU crystal burden and traditional cardiovascular risk factors needs to be studied. Were they to be correlated, quantifying MSU deposition could help identify gout patients at high cardiovascular risk.

Ultrasonography (US) and dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) are two imaging techniques that can visualize and provide a quantification of the MSU burden [8]. DECT uses two x-ray beams with two different energies allowing us to distinguish between urate and calcium in soft tissues surrounding bone when the volume of deposits exceeds 0.01 cm3 [9, 10]. US, on the other hand, can identify intra-articular cartilage MSU deposition appearing as a double contour (DC) sign which disappears during urate depletion [11]. Both techniques can quantify tophi volume but do not provide the same measurements [8].

The main objective of this study was to explore the relationship between the extent of MSU deposition, assessed with US and DECT, and cardiovascular risk assessment.

Methods

Patients

Consecutive patients with a diagnosis of gout according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2015 criteria [12] were prospectively recruited to undergo a quantification of urate deposition in the knees and feet using US and DECT [8], and an assessment of their cardiovascular risk. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Lille Catholic Hospitals and all participants provided informed consent before inclusion into the study.

At the initial clinical visit, the following were recorded: demographic details, comorbid disorders (particularly prior major cardiovascular events), gout history, medications, and physical examination (including measures of body mass index (BMI) and arterial blood pressure (BP)). Laboratory testing of SU levels, lipid levels, blood glucose, and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measured by CKD-EPI or MDRD was to be performed within the 2 weeks of US and DECT examinations.

Cardiovascular risk assessment and the metabolic syndrome

Traditional cardiovascular risk factors were systematically assessed: BP, BMI, blood glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, calculated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and smoking status. Cardiovascular risk was then calculated using the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines [13], the Framingham general 10-year cardiovascular risk factors [14], and the Framingham 10-year risk of coronary disease [15]. These scores could not be calculated for patients whose age was outside the respective range of applicability and for participants with a prior history of coronary heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, and stroke. The metabolic syndrome was defined by the presence of three out of five items among the following: obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2 in the absence of available waist circumference measurements), elevated BP (systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mmHg or on-going antihypertensive therapy), elevated triglycerides (≥ 15 mg/dL or on-going treatment), low HDL cholesterol (≤ 40 mg/dL in men and ≤ 50 mg/dL in women or on-going treatment), and hyperglycemia (≥ 100 mg/dL or drug treatment for elevated blood glucose) [16].

US examination

Examinations were performed by one of four trained musculoskeletal radiologists (JFB, NN, BC, or JL) on an Applio 400 US machine (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tochigi, Japan). High-frequency probes were used: a 12-Mhz probe for knee examination and an 18-MHz probe for ankle and foot examination. US examination for the DC sign was performed on the femoro-patellar joints, talo-crural joints, and first metatarsophalangeal joints [17].

CT data acquisition and image reconstruction

All scans were performed using a single-source CT (Somatom Definition Edge; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The patients were positioned feet first in a supine position. Knees and feet were scanned axially in two separate acquisitions performed consecutively on the same day. All scans were performed with the same image protocol, acquisition at 128 × 0.6 mm, and pitch of 0.7. For each body part, two scans were acquired with tube potentials of 80 kV and 140 kV. Depending on the scanned body region, quality reference tube currents ranged between 62 and 260 mAs. Automated attenuation-based tube current modulation was used in all examinations.

Axial images with soft (B30f) and bone (B70f) convolution kernels were reconstructed with a 1-mm slice thickness and an increment of 1 mm. DECT postprocessing was performed by the radiologists with dedicated software (syngo.via VB10B, syngo Dual Energy Gout; Siemens), following the parameters described elsewhere [18]: UH threshold, 150; iodine ratio, 1.4; material definition ratio, 1.25; resolution, 4; air distance, 5; bone distance, 10. Two kinds of images were reconstructed for each body part. First, volume-rendered three-dimensional (3D) images in which urate crystal deposits coded in green were reconstructed with a bone tissue convolution kernel (B70f). These images allowed a straightforward overview of MSU deposits. Second, multiplanar reformations associating images reconstructed with a soft tissue kernel (B30f) and colored images were reconstructed. The aspect of the final fusion images could be changed by modulating the relative percentages of the morphological and colored images from 0 to 100% with a slider.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the R software (version 3.4.2). Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation, and qualitative variables as number and percentage.

Two-by-two correlations of quantitative variables were assessed by the Spearman correlation coefficient given the absence of normal distribution of values. Tests for nullity of coefficients were performed.

DECT volumes of urate deposition, the number of joints with the DC, and SU levels were compared between the groups of patients presenting with and without the metabolic syndrome using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test as data were not normal.

The significance level was set at 5%.

The primary endpoint was the Spearman correlation coefficient ρ between DECT MSU volume deposited on the feet and cardiovascular risk.

Results

0f the 50 patients included, eight were excluded since lipid and glucose levels were not collected. The remaining 42 patients included were predominantly male (40/42) and aged 63.0 ± 13.2 years. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Of these 42 patients, 33 had no prior coronary heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, or stroke, and therefore could have their cardiovascular risk scores calculated.

Overall, 29/42 had at least one US tophus of 1.1 ± 1.4 cm3. Patients presented with 2.2 ± 1.0 joints with the DC sign out of 6 (median 2, interquartile range (IQR) 2–3). The volume of MSU deposits with DECT was 2.7 ± 6.7 cm3 for the feet (median 0.7 cm3, IQR 0.1–2.2) and 1.9 ± 4.6 cm3 for the knees (median 0.2 cm3, range 0–1.2) (Fig. 1). Correlations between SU levels and DECT volumes of MSU deposits of the knees, feet, and knees + feet were weak (ρ = 0.28, 0.20, and 0.23, respectively). Overall, 28/42 patients presented with the metabolic syndrome and the average 10-year coronary event or stroke risk according to the ACC/AHA (n = 33) was high (21 ± 15%).

Imaging of monosodium urate crystal deposition. a Double contour sign of intra-articular cartilage deposition of the femoro-patellar joint (arrows), (b) large (volume 5.39 cm3) and (c) small (volume 0.02 cm3) soft tissue volumes of deposits on the feet visualized with dual-energy computed tomography

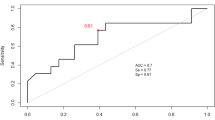

Correlations between DECT volumes of MSU deposits in the knees, feet, and knees + feet and cardiovascular risk according to the ACC/AHA were very poor, with ρ = 0.18, −0.01, and 0.13, respectively (Fig. 2), and did not differ significantly from zero (p > 0.05). The was no correlation between the number of joints with the DC sign and cardiovascular risk (ρ = −0.07) and the correlation was very poor with SU levels (ρ = 0.15). DECT MSU deposit volume was similar in patients with and without metabolic syndrome (p = 0.29) (Table 2). Correlations between the urate burden assessed by SU levels, the number of joints with the DC sign, and DECT volumes of MSU deposition and individual cardiovascular risk factors are weak to null, and are shown in Fig. 3.

Correlation between the dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) volumes of monosodium urate deposition and the assessment of the risk of coronary heart disease or stroke according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), and the assessment of the Framingham coronary heart disease and general cardiovascular disease risks

Discussion

This study found no, or only very weak, correlation between levels of overall cardiovascular risk and the extent of urate burden in the knees and feet measured using DECT and US. Urate burden was not associated with the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome. Some weak correlations were established between individual components of cardiovascular risk, notably serum triglyceride levels.

Correlations between urate burden and cardiovascular risk were particularly weak when considering measurements of the feet only. These results are in direct contrast with the conclusions recently made by Lee et al. from their retrospective study [19], considering that there was a correlation between total DECT urate volume of the feet and both the 10-year Framingham risk for cardiovascular disease and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome [19]. Explanations for these discrepancies include biases inherent to retrospective studies that may have affected the study from Lee et al., both the fact that no mention was made on the exclusion of patients with prior major cardiovascular factors for whom cardiovascular risk scores are not applicable, and also potential differences between gout and cardiovascular comorbidities across populations [20, 21], in this case of European and Asian origin. Furthermore, when looking directly at the numbers, the Spearman correlation coefficient for volumes of urate deposition of the feet and the 10-year Framingham risk score for general cardiovascular disease was −0.07 (very weakly negatively correlated to no correlation) in our study but only 0.22 (weak correlation) in the study by Lee et al. [19].

Despite a known higher prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the population of gout patients, it does not seem to be related to the extent of urate burden [22]. This result is consistent with previous results from the study by Lee et al. in which the metabolic syndrome was not associated with the volume of urate deposition in multivariate analysis [19]. Surprisingly, despite a known trend of increasing SU levels with BMI [23], all volumes of MSU deposits measured with DECT were negatively weakly correlated to the BMI. A technical explanation could be that it is known that visceral fat increases noise in the 80 kV images [24]; this remains to be shown for peripheral joints. A weak negative correlation of the prevalence of the DC sign with the BMI was also found, which could also be explained by the difficulty of observing joints with US with greater surrounding adipose tissue. However, so far, no study has reported difficulties in the search for the DC sign in peripheral joints of obese patients.

Cholesterol abnormalities (increased LDL and decreased HDL cholesterol) are weakly associated with joint MSU deposition. Our study found a weak association of HDL levels with intra-articular MSU deposition assessed with the US DC sign, urate burden of the knees with DECT, and SU levels, and a weak association between LDL levels and the DC sign only. These weak or very weak correlations are consistent with the results from the third NHANES which showed an increased prevalence of low HDL in gout patients, but to a far lesser extent than the high prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia [22]. It is unclear whether these correlations are only due to the same correlations between LDL and HDL levels with SU that are similar.

An increase in triglyceride levels in gout is weakly associated with an increased MSU soft tissue deposition measured with DECT. Genetic associations showed that mutations in the apolipoprotein gene cluster play a causal role in gout, even after adjustment for lipid and SU levels [21]. Apolipoprotein plays a central role in lipid metabolism and, notably, in the transport of triglycerides. A study using Mendelian randomization has previously shown the causal role of triglycerides in raising SU levels in men, but the reverse was not true [25]. Elevations of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-triglycerides may be implicated in the transition between asymptomatic hyperuricemia and gout [20]. One of the explanations for the association between lipid modifications and gout would be that lipids are of importance in the coating of MSU crystals and that modifications of this coating has implications on the inflammatory response to the presence of these crystals [26]. The correlation between triglyceride levels and MSU burden found in our study suggests that not only do triglycerides increase circulating urate but are also possibly involved in MSU deposition itself.

We acknowledge that this study presents with some limitations. The first one is sample size, which limited our ability to establish the precise level of the correlations studied. Second, the fact that most gout patients had significant cardiovascular risk as shown in other studies made identifying factors able to discriminate between levels of risk difficult [6]. Nonetheless, given the fact that all correlations found were null to weak, it seems improbable that a strong correlation has been missed using our methodology. The third limitation is inherent to the cross-sectional nature of the study itself as it cannot establish a correlation between urate burden and prevalence of cardiovascular events. The present study can only establish whether there is a link between MSU burden and cardiovascular risk factors. A longitudinal study is necessary to explore if the MSU burden is an independent risk for cardiovascular events.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that, while the quantity of urate burden is involved in the association of gout with increased cardiovascular events, it does not seem to be through an overall increase in traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The extent of MSU burden does not increase the estimated risk of cardiovascular events and, thus, quantifying the MSU burden is not a surrogate marker for traditional cardiovascular risk assessment of gout patients naive of urate lowering therapy.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

American College of Cardiology

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- DC:

-

Double contour

- DECT:

-

Dual-energy computed tomography

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- MSU:

-

Monosodium urate

- SU :

-

Serum urate

- US :

-

Ultrasonography

References

Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet. 2016;388:2039–52.

Richette P, Perez-Ruiz F, Doherty M, Jansen TL, Nuki G, Pascual E, Punzi L, So AK, Bardin T. Improving cardiovascular and renal outcomes in gout: what should we target? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:654–61.

Bardin T, Richette P. Impact of comorbidities on gout and hyperuricaemia: an update on prevalence and treatment options. BMC Med. 2017;15:123.

Singh JA, Ramachandaran R, Yu S, Yang S, Xie F, Yun H, Zhang J, Curtis JR. Is gout a risk equivalent to diabetes for stroke and myocardial infarction? A retrospective claims database study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:228.

Perez-Ruiz F, Martinez-Indart L, Carmona L, Herrero-Beites AM, Pijoan JI, Krishnan E. Tophaceous gout and high level of hyperuricaemia are both associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:177–82.

Andres M, Bernal JA, Sivera F, Quilis N, Carmona L, Vela P, Pascual E. Cardiovascular risk of patients with gout seen at rheumatology clinics following a structured assessment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210357.

Borghi C, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, De Backer G, Dallongeville J, Medina J, Nuevo J, Guallar E, Perk J, Banegas JR, Tubach F, et al. Serum uric acid levels are associated with cardiovascular risk score: a post hoc analysis of the EURIKA study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;253:167–73.

Pascart T, Grandjean A, Norberciak L, Ducoulombier V, Motte M, Luraschi H, Vandecandelaere M, Godart C, Houvenagel E, Namane N, et al. Ultrasonography and dual-energy computed tomography provide different quantification of urate burden in gout: results from a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:171.

Choi HK, Al-Arfaj AM, Eftekhari A, Munk PL, Shojania K, Reid G, Nicolaou S. Dual energy computed tomography in tophaceous gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1609–12.

Bayat S, Aati O, Rech J, Sapsford M, Cavallaro A, Lell M, Araujo E, Petsch C, Stamp LK, Schett G, et al. Development of a dual-energy computed tomography scoring system for measurement of urate deposition in gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:769–75.

Ottaviani S, Gill G, Aubrun A, Palazzo E, Meyer O, Dieude P. Ultrasound in gout: a useful tool for following urate-lowering therapy. Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82:42–4.

Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, Fransen J, Schumacher HR, Berendsen D, Brown M, Choi H, Edwards NL, Janssens HJ, et al. Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;2015(74):1789–98.

Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;2014(129):S49–73.

D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–53.

Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–47.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC Jr, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Gutierrez M, Schmidt WA, Thiele RG, Keen HI, Kaeley GS, Naredo E, Iagnocco A, Bruyn GA, Balint PV, Filippucci E, et al. International consensus for ultrasound lesions in gout: results of Delphi process and web-reliability exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1797–805.

Finkenstaedt T, Manoliou A, Toniolo M, Higashigaito K, Andreisek G, Guggenberger R, Michel B, Alkadhi H. Gouty arthritis: the diagnostic and therapeutic impact of dual-energy CT. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3989–99.

Lee KA, Ryu SR, Park SJ, Kim HR, Lee SH. Assessment of cardiovascular risk profile based on measurement of tophus volume in patients with gout. Clin Rheumatol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3963-4.

Rasheed H, Hsu A, Dalbeth N, Stamp LK, McCormick S, Merriman TR. The relationship of apolipoprotein B and very low density lipoprotein triglyceride with hyperuricemia and gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:495.

Rasheed H, Phipps-Green AJ, Topless R, Smith MD, Hill C, Lester S, Rischmueller M, Janssen M, Jansen TL, Joosten LA, et al. Replication of association of the apolipoprotein A1-C3-A4 gene cluster with the risk of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1421–30.

Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:109–15.

Lyngdoh T, Vuistiner P, Marques-Vidal P, Rousson V, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Bochud M. Serum uric acid and adiposity: deciphering causality using a bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39321.

Karcaaltincaba M, Aktas A. Dual-energy CT revisited with multidetector CT: review of principles and clinical applications. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2011;17:181–94.

Rasheed H, Hughes K, Flynn TJ, Merriman TR. Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for a causal role of serum urate in increasing serum triglyceride levels. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:830–7.

Ortiz-Bravo E, Sieck MS, Schumacher HR Jr. Changes in the proteins coating monosodium urate crystals during active and subsiding inflammation. Immunogold studies of synovial fluid from patients with gout and of fluid obtained using the rat subcutaneous air pouch model. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1274–85.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TP designed the study, participated in clinical data collection, analyzed data, and participated in the writing of the manuscript. AG participated in clinical data collection and in the writing of the manuscript. LN performed the statistical analyses. VD, MM, HL, MV, CG, and EH contributed to patient recruitment and a critical review of the manuscript. NN, JL, and BC performed US examinations and read DECT scans. JFB designed the study, performed US examinations, read DECT scans, and participated in the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was received from the Institutional Medical Ethics Review Board of the Lille Catholic Hospitals (reference number 2016–04-06). All patients provided informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pascart, T., Capon, B., Grandjean, A. et al. The lack of association between the burden of monosodium urate crystals assessed with dual-energy computed tomography or ultrasonography with cardiovascular risk in the commonly high-risk gout patient. Arthritis Res Ther 20, 97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1602-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1602-3