Abstract

Background

Dirofilaria repens is a filarioid nematode transmitted by mosquitoes. Adult D. repens are typically localized in the subcutaneous tissue of the host, but other, atypical localizations have also been reported. There have been several reports of clinical cases involving an association of parasites and hernias in both animals and humans. However, it is unclear if parasitic infection can act as a triggering factor in the development of hernias.

Methods

A 12-year-old dog was referred to a private veterinarian clinic in Satu Mare, northwestern Romania due to the presence of a swelling in the lateral side of the penis (inguinal area). The dog underwent hernia repair surgery during which four long nematodes were detected in the peritoneal serosa of the inguinal hernial sac. One female specimen was subjected to genomic DNA extraction to confirm species identification, based on amplification and sequencing of a 670-bp fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene. Treatment with a single dose of imidacloprid 10% + moxidectin 2.5% (Advocate, Bayer AG) was administered.

Results

The nematodes were morphologically identified as adult D. repens, and the BLAST analyses revealed a 100% nucleotide similarity to a D. repens sequence isolated from a human case in Czech Republic.

Conclusions

We report a case of an atypical localization of D. repens in the peritoneal cavity of a naturally infected pet dog with inguinal hernia and discuss the associations between hernia and parasitic infections.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Dirofilaria (Spirurida, Onchocercidae) includes vector-borne filarial nematodes with a worldwide distribution. Subcutaneous dirofilariasis is a common disease of both dogs and cats, but also of wild carnivores and humans [1]. Dirofilaria repens is transmitted by mosquitoes. Adult nematodes are typically localized in the subcutaneous tissues of the host where they freely move while microfilariae circulate in the blood stream where they are ingested by female mosquitoes [2,3,4,5]. Atypical localizations of the adult nematodes have also been reported [1, 6,7,8,9]. Infection with D. repens is associated with subcutaneous nodules, hyperpigmentation or, in most cases, no symptoms at all [10, 11]. Subclinically infected animals often remain undiagnosed due to the absence of any clinical signs, and they may represent important reservoirs for the spread of D. repens with zoonotic implications [12].

Several clinical cases involving an association of helminth parasites and hernias have been reported in both animals [6] and humans [13,14,15,16] (Table 1). However, it remains unclear whether parasitic infection can act as a triggering factor in the development of hernias. The authors of one study suggest that nematodes may act as an etiological agent of hernias [17], and several other studies have reported that certain nematodes can be responsible for hydrocele, which can in turn be complicated with inguinal hernia [18, 19].

The aim of this study was to describe a case of an atypical subclinical infection with D. repens in the peritoneal cavity of a naturally infected pet dog with inguinal hernia and to review and discuss the associations between hernia and parasitic helminth infections.

Methods

A 12-year-old male, mixed breed dog was referred to a private clinic (Sabados Vet) in the city of Satu Mare, north-western Romania, on 24 April 2020 due to the presence of a swelling in the postero-lateral side of the penis (inguinal area). The dog was housed indoors, with daily access to the outside environment. A complete clinical examination was performed, and no other health issues were detected, other than what proved to be an inguinal hernia when palpated. An abdominal ultrasound examination was carried out to elucidate the cause of the swelling and a blood sample was collected for a complete laboratory evaluation. The animal underwent hernia repair surgery the following day during which four long nematodes were detected on the surface of the peritoneal serosa of the inguinal hernial sac. Grossly, the affected tissue was diffusely and moderately congested and thickened and showed numerous, prominent and white nodules disseminated on the surface of the peritoneum, consisting of lymphoid cells aggregates (milky spots). The non-strangulated hernial sac contained portions of small intestine and greater omentum. No significant free fluid was observed at this level (Fig. 1).

The nematodes were collected and stored in absolute ethanol and sent together with a blood sample collected in EDTA tubes to the Department of Parasitology and Parasitic Diseases (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca) for morphological and molecular identification of the adult nematodes and for a modified Knott’s test, respectively. The collected nematodes were morphologically identified using descriptions provided in [20]. One female specimen was subjected to genomic DNA extraction in order to confirm species identification, based on amplification and sequencing of a 670-bp fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1), as previously described [21]. Genomic DNA was also isolated from 200 μl of whole blood and further processed by means of multiplex PCR [22] to exclude other species of blood-circulating microfilariae which are known to be present in Romania.

After the identification of the nematodes, the dog was treated with a single dose of imidacloprid 10% + moxidectin 2.5% (Advocate; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany) in the clinic and the owner was advised to repeat the treatment monthly. Unfortunately, the dog had not been a regular patient of the clinic, with the present case being the first time it had been examined at the clinic; no information on past routine deworming and ectocide treatments was available.

Six months after the initial worm treatment, the dog was referred to the clinic for a control examination, and a second blood sample was collected to evaluate the efficacy of the treatment using Knott’s test. The owner was advised to use insect repellents at monthly intervals as prophylactic treatment.

Results

The abdominal ultrasound performed at the first visit did not reveal any specific abnormalities, with the exception of an inguinal hernia. Blood analyses showed a total white blood cell count of 15.15 thousands/mm3 (reference interval [RI] 6–17), lymphocytosis (38.0%; RI 10.0–30.0%), monocytosis (14.9%; RI 2–10%), eosinophilia (11.2%; RI 1.6–7.5%) and neutropenia (35.6%; RI 50.0–80.0%). The results of all biochemical tests were within normal values, except for moderate hypokalemia (3.1 mmol/l; RI 3.5–5.6 mmol/L).

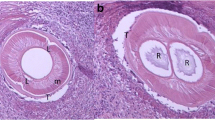

All nematodes were morphologically identified as D. repens adults (two males and two females). The specimens presented a striated cuticle with longitudinal ridges on the surface. The female nematodes were 4.9–6.1 mm wide and 15.3–17.1 cm long; the males were 3.9–4.2 mm wide and 6.4–7.2 cm long. The Knott’s test revealed the presence of microfilariae morphologically identified as D. repens (Fig. 2). The microfilariae were 5.8–7.8 µm wide and 330–374 µm long and had a rounded anterior extremity and well-developed sub-cephalic space; the caudal extremity was generally curved. No co-infection with D. immitis or Acanthocheilonema reconditum was observed microscopically, nor detected by multiplex PCR. The BLAST analyses revealed a 100% nucleotide similarity to a D. repens sequence isolated from a human case in Czech Republic (Accession number KR998257). Our sequence was deposited in GenBank under the accession number MW065790. After 6 months, the dog had no visible cutaneous nodules, but the second blood sample collected at the same time was still positive for D. repens because the owner had neglected to follow the clinic’s recommendation to repeat the treatment monthly.

Discussion

Inguinal hernias in mammals are very common and may be produced by traumatic factors, intense effort, or in association with a congenital background. The presence of parasitic infections associated with hernias has been reported previously. Among the parasites associated with hernias, filarial parasites are the most common. In Africa and the Americas, the nematode most frequently associated with hernias is Wuchereria bancrofti, while in Europe, most of the parasite–hernias associations reported have involved Dirofilaria spp. (Table 1). There has also been a recent report of an extra-gastrointestinal anisakidosis caused by Pseudoterranova azarasi that manifested as strangulated inguinal hernia: the presence of nematodes within peritoneal serosa of the inguinal hernia sac was associated with severe granulomatous inflammation and numerous eosinophils [23]. In our case, during surgery we macroscopically detected a localized serosal inflammatory reaction with severe edema, possibly suggesting a role of filarial-induced peritoneal inflammation in the development of inguinal hernia. The edematous changes with disruption of the collagen fibers in the submesothelium can be caused by the direct effect of the parasites and/or by an impairment and dysfunction of lymphatic drainage. Evidence of numerous and prominent “milky spots” on the surface of the affected peritoneal serosa is another sign of peritoneal inflammation [24]. Enlargement of the inguinal and subinguinal lymph nodes, lymphangitis, lymphangiectasia and scrotal edema are common signs of the presence of filarial parasites in human patients [17]. However, we did not observe any changes to the lymphatic system in our canine patient. Visceral infections with protozoan organisms, including Leishmania donovani [25] and Toxoplasma gondii [26], have been reported to be associated with hernias in humans. In these cases, the abdominal hernia was likely caused by (i) protozoan infection-related hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, resulting in increased abdominal pressure; (ii) alterations to the skeletal muscles (e.g. degeneration and disruption) of the abdominal wall; or (iii) changes to the peritoneal serosa. Dirofilaria immitis is a well-known parasite and is responsible for severe symptoms in dogs, while D. repens is occasionally produces mild dermatological lesions [27]. Humans can be accidental hosts when they are infected by D. repens, but these nematodes do not usually reach maturity in humans and they erratically migrate through the body to form subcutaneous nodules [28,29,30,31]. However, on occasion D. repens can produce atypical and severe lesions, as described in a case from a human patient in Romania [32].

Even though it is still only a hypothesis that parasites may play a role in the pathophysiology of hernias, our case involves the detections of a D. repens infection during surgery for a non-strangulated inguinal hernia. Knott [17] suggested that filarial hydrocele can produce an inguinal hernia due to the weight of the sac, impaired lymph circulation and lengthening of the cord, which can dilate the inguinal canal and drag down the peritoneal serosa [17]. Another theory is that a parasitic infection could induce granulomatous or muscular pathological reactions in the host [33] and that these may be responsible for collagen degeneration, resulting in an inguinal hernia [34]. Rodhain [35] considered that hanging groins are produced by allergic reactions to microfilariae of O. volvulus, a condition that is responsible for producing complications such as a hernia [35, 36].

In the case of our canine patient, we recommended prophylactic treatment, even though the locality is not considered to be a risk area for infection with heartworms, although this may be due to the absence of studies in this field in northwestern Romania [26, 36]. Both veterinarians and medical doctors should consider dirofilariasis as a diagnostic option, especially in endemic areas. It should be noted that the clinical aspect of this disease is not always typical and may lead to severe complications, even in dog owners [8, 32, 37, 38].

Conclusions

This is the first report of a parasite-associated inguinal hernia in a dog. The relatively numerous publications on helminth-associated hernias, as well as other pathophysiological effects, suggest a possible involvement of parasites in this surgical condition in humans and dogs. The present case also extends the known geographical distribution of D. repens in Romania and highlights the importance of promoting control and prophylactic measures by reducing the mosquito’s populations and treating infected dogs which can serve as reservoir hosts. These measures are highly important in order to minimize the transmission to other hosts, given the zoonotic potential of D. repens.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Pierantozzi M, Di Giulio G, Traversa D, Aste G, Di Cesare A. Aberrant peritoneal localization of Dirofilaria repens in a dog. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2017;10:62–4.

Genchi C, Venco L, Magnino S, Di Sacco B, Perera L, Bandi C, et al. Aggiornamento epidemiologico sulla filariosi del cane e del gatto. Veterinaria. 1993;2:5–11. (In Italian).

Tarello W. La dirofilariose sous-cutanée à Dirofilaria (Noochtiella) repens chez le chien. Revue bibliographique et cas clinique. Rev Med Vet. 1999;150:8–9. (In Italian).

Anderson RC. Nematode parasites of vertebrates. Their development and transmission. Wallingford: CABI; 2000.

Otranto D, Brianti E, Latrofa MS, et al. On a Cercopithifilaria sp. transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus: a neglected, but widespread filarioid of dogs. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:1.

Sim C, Kim HC, Son HY, Jung JY, Ryu SY, Park BK. Description of peritoneal cavity dirofilariosis caused by Dirofilaria immitis (Filarioidea: Onchocercidae) in a dog: a case report. Vet Med. 2013;58(2):105–8.

Petry G, Genchi M, Schmidt H, Schaper R, Lawrenz B, Genchi C. Evaluation of the adulticidal efficacy of imidacloprid 10%/moxidectin 2.5%(w/v) spot-on (Advocate®, Advantage® Multi) against Dirofilaria repens in experimentally infected dogs. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(1):131–44.

Mircean M, Ionică AM, Mircean V, Györke A, Codea AR, Tăbăran FA, et al. Clinical and pathological effects of Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis in a dog with a natural co-infection. Parasitol Int. 2017;66(3):331–4.

Napoli E, Bono V, Gaglio G, Giannetto S, Zanghì A, Otranto D, et al. Unusual localization of Dirofilaria repens (Spirurida: Onchocercidae) infection in the testicle of a dog. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;66:101326.

Kamalu BP. Canine filariasis caused by Dirofilaria repens in southeastern Nigeria. Vet Parasitol. 1991;40(3–4):335–8.

Albanese F, Abramo F, Braglia C, Caporali C, Venco L, Vercelli A, et al. Nodular lesions due to infestation by Dirofilaria repens in dogs from Italy. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:255–6.

Genchi C, Kramer LH, Rivasi F. Dirofilarial infections in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11(10):1307–17.

Abbas KF, El-Monem SGA, Malik Z, Khan AM. Surgery still opens an unexpected bag of worms! An intraperitoneal live female Dirofilaria worm: case report and review of the literature. Surg Infect. 2006;7(3):323–5.

Theis JH, Gilson A, Simon GE, Bradshaw B, Clark D. Case report: unusual location of Dirofilaria immitis in a 28-year-old man necessitates orchiectomy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(5):317–22.

Matějů J, Chanová M, Modrý D, Mitková B, Hrazdilová K, Žampachová V, et al. Dirofilaria repens: emergence of autochthonous human infections in the Czech Republic. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):171.

Monnier S, Chevreau G, Bruneel E, Blanc C, Meckenstock R, Thereby A, et al. An unusual inguinal hernia. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;41:e1–2.

Knott J. Filariasis of the testicle due to Wuchereria bancrofti. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1939;33(3):335–47.

Dandapat MC, Mohapatro SK, Mohanty SS. The incidence of filaria as an aetiological factor for testicular hydrocele. Br J Surg. 1986;73(1):77–8.

Noroes J, Addiss D, Cedenho A, Figueredo-Silvan J, Lima G, Dreyer G. Pathogenesis of filarial hydrocele: risk associated with intrascrotal nodules caused by death of adult Wuchereria bancrofti. T Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97(5):561–6.

Demiaszkiewicz AW, Polanczyk G, Osinska B, Pyziel AM, Kuligowska I, Lachowicz J. Morphometric characteristics of Dirofilaria repens Railliet et Henry, 1911 parasite of dogs in Poland. Wiad Parazyt. 2011;57(4).

Casiraghi MT, Anderson JC, Bandi C, Bazzocchi C, Genchi C. A phylogenetic analysis of filarial nematodes: comparison with the phylogeny of Wolbachia endosymbionts. Parasitology. 2001;122(1):93–103.

Latrofa MS, Montarsi F, Ciocchetta S, Annoscia G, Dantas-Torres F, Ravagnan S, et al. Molecular xenomonitoring of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in mosquitoes from north-eastern Italy by real-time PCR coupled with melting curve analysis. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5(1):76.

Mitsuboshi A, Yamaguchi H, Ito Y, Mizuno T, Tokoro M, Kasai M. Extra-gastrointestinal anisakidosis caused by Pseudoterranova azarasi manifesting as strangulated inguinal hernia. Parasitol Int. 2017;66(6):810–2.

Michailova KN, Usunoff KG. The milky spots of the peritoneum and pleura: structure, development and pathology. Biomed Rev. 2004;15:47–66.

Zhang G, Zhong J, Wang T, Zhong L. A case of visceral leishmaniasis found by left oblique hernia: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(4):2697–701.

Alvarado-Esquivel C, Estrada-Martínez S. Toxoplasma gondii infection and abdominal hernia: evidence of a new association. Parasites Vectors. 2011;4(1):112.

Ionică AM, Matei IA, Mircean V, Dumitrache MO, D’Amico G, Győrke A, et al. Current surveys on the prevalence and distribution of Dirofilaria spp. and Acanthocheilonema reconditum infections in dogs in Romania. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(3):975–82.

Petrocheilou V, Theodorakis M, Williams J, Prifti H, Georgilis K, Apostolopoulou I, et al. Microfilaremia from a Dirofilaria-like parasite in Greece. Apmis. 1998;106(1–6):315–8.

Pampiglione S, Rivasi F. Dirofilariasis. In: Service MW, editor. The encyclopedia of arthropod-transmitted infections. Wallingford: CABI; 2001. p.143–150.

Mănescu R, Bărăscu D, Mocanu C, Pîrvănescu H, Mîndriă I, Bălăşoiu M, et al. Subconjunctival nodule with Dirofilaria repens. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2009;104(1):95–7. (In Romanian).

Damle AS, Iravane JA, Khaparkhuntikar MN, Maher GT, Patil RV. Microfilaria in human subcutaneous dirofilariasis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(3):113.

Popescu I, Tudose I, Racz P, Muntau B, Giurcaneanu C, Poppert S. Human Dirofilaria repens infection in Romania: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:472976. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/472976.

Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Petersdorf RG, Wilson JD, Fauci AS, Martin JB, et al. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1988.

Wu CC, Liao WS, Kao MS, Huang SC, Shen BY. Inguinal hernia with incidental parasitic infection: a case report and literature review. Urol Sci. 2012;23(1):26–7.

Rodhain J. Adenolymphoceles in the Belgian Congo. Inst Roy Colonial Beige Sect des Sci Naturelles Med Mem. 1952;21:5.

Nelson GS. “Hanging groin” and hernia, complications of onchocerciasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1958;52(3):272–5.

Ciucă L, Musella V, Miron LD, Maurelli MP, Cringoli G, Bosco A, et al. Geographic distribution of canine heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in stray dogs of eastern Romania. Geospat Health. 2016;11(3). https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2016.499.

D’Amuri A, Floccari F, De Caro F, Filotico M. Histopathological diagnosis of human Dirofilaria repens infection: report on three cases with unusual sites of involvement. Int J Sci Res 2017; 6(12).

Coley BL, Lewis B. Filarial funiculitis: report of a case discovered at operation for inguinal hernia. Am J Surg. 1948;76(1):15–22.

Young AE, Kinmonth JB. Filariasis. J R Soc Med 1976;708–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591577606900927.

Ahorlu CK, Dunyo SK, Koram KA, Nkrumah FK, Aagaard-Hansen J, Simonsen PE. Lymphatic filariasis related perceptions and practices on the coast of Ghana: implications for prevention and control. Acta Trop. 1999;73(3):251–61.

Salahi-Moghadam A, Banihashemi H. Unusual location of Dirofilaria immitis in a 5-year-old boy’s hydrocele: a case report. Hormoz Med J. 2016;20(3):210–3.

Takekawa Y, Kimura M, Sakakibara M, Yoshii R, Yamashita Y, Kubo A, et al. Two cases of parasitic granuloma found incidentally in surgical specimens. Rinsho byori. Jpn J Clin Pathol. 2004;52(1):28–31.

Hajjar R, Chakravarti A, Malaekah H, Schwenter F, Lemieux C, Maietta A, et al. Anisakiasis in a Canadian patient with incarcerated epigastric hernia. IDCases. 20;2020:e00715.

Ludlow AI. Inguinal Hernia: ova of Schistosoma japonicum in hernial sac. Chin Med J. 1924;38(10).

Pawel BR, Osman J, Nance ML, McGowan KL. Schistosomiasis: an unexpected finding in an inguinal hernia sac. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008;11(5):402–4.

Hayashi K, Igari D. A case of nodules at bottom of hernia-sac in scrotum, caused by eggs of Paragonimus westermani. Taiwan Igakkai Zasshi. 1927;269.

Choy PD, Ludlow AI. Paragonimus westermanii encysted in the sac of inguinal hernia. Chin Med J 1931;45(6).

Singh NB, Chitale AM, Yadav VK. Parietal abdominal wall swelling turning out to be a parietal complication of hydatid cyst of liver—a case report. Int J Health Sci Res. 2014;4:246–51.

Malekpour-Alamdari N, Gholizadeh B, Kimia F. Inguinal canal hydatidosis presenting as irreducible inguinal hernia: a case report. Acad J Surg. 2017;4(3):87–9.

Potters I, Desaive C, Van Den Broucke S, Van Esbroeck M, Lynen L. Unexpected infection with Armillifer parasites. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(12):2116.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The first author was financially supported by Altius SRL Romania through a grant aimed to support and promote research in Romania.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GD identified the nematodes and wrote the manuscript, AMI performed the molecular biology diagnosis, IS performed the hernia surgery and detected the nematodes, MT provided useful information and references regarding the pathology, ADM coordinated the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Deak, G., Ionică, A.M., Szasz, I. et al. A case of inguinal hernia associated with atypical Dirofilaria repens infection in a dog. Parasites Vectors 14, 125 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04635-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04635-3