Abstract

Background

Despite the licensure of the world’s first dengue vaccine and the current development of additional vaccine candidates, successful Aedes control remains critical to the reduction of dengue virus transmission. To date, there is still limited literature that attempts to explain the spatio-temporal population dynamics of Aedes mosquitoes within a single city, which hinders the development of more effective citywide vector control strategies. Narrowing this knowledge gap requires consistent and longitudinal measurement of Aedes abundance across the city as well as examination of relationships between variables on a much finer scale.

Methods

We utilized a high-resolution longitudinal dataset generated from Singapore’s islandwide Gravitrap surveillance system over a 2-year period and built a Bayesian hierarchical model to explain the spatio-temporal dynamics of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in relation to a wide range of environmental and anthropogenic variables. We also created a baseline during our model assessment to serve as a benchmark to be compared with the model’s out-of-sample prediction/forecast accuracy as measured by the mean absolute error.

Results

For both Aedes species, building age and nearby managed vegetation cover were found to have a significant positive association with the mean mosquito abundance, with the former being the strongest predictor. We also observed substantial evidence of a nonlinear effect of weekly maximum temperature on the Aedes abundance. Our models generally yielded modest but statistically significant reductions in the out-of-sample prediction/forecast error relative to the baseline.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that public residential estates with older buildings and more nearby managed vegetation should be prioritized for vector control inspections and community advocacy to reduce the abundance of Aedes mosquitoes and the risk of dengue transmission.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dengue fever is a rapidly emerging vector-borne disease mainly transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus [1], causing an estimated number of 390 million infections per year worldwide [2]. Clinical manifestations of dengue infection range from mild fever to potentially lethal complications such as dengue shock syndrome [1]. Despite the licensure of the world’s first dengue vaccine and the current development of additional vaccine candidates [3], successful vector control remains critical to the reduction of dengue virus transmission [4]. Moreover, the benefits of Aedes population control extend beyond dengue infection prevention alone, given the multiple diseases that can be transmitted by these mosquito species, such as Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever.

Previous work has yielded important insights into the behaviors and ecology of the main dengue vectors. Both Aedes species can easily disperse throughout areas with ~ 300 m radius to seek oviposition sites [5]. The Ae. aegypti mosquitoes in particular have become a highly efficient vector for dengue transmission owing to their skip oviposition behavior (i.e. deposit eggs from the same batch in multiple sites), desiccation-resistant eggs, preference for human biting, multiple feeds per gonotrophic cycle, and adaptation to reside and breed in human habitats, among other factors [6]. The Ae. albopictus mosquitoes were found to have a relatively lower contribution to the reported dengue cases overall despite their high competence for dengue transmission, which is primarily attributed to aspects of their ecology [7]. Both environmental and anthropogenic factors can exert an important influence on the distribution of Aedes mosquitoes [8,9,10,11,12], and modeling studies have been carried out to map the suitability and distribution of the main dengue vectors at a global scale [10,11,12]. However, there is still very limited literature that attempts to explain the spatio-temporal population dynamics of Aedes mosquitoes within a single city [13], which hinders the development of more effective citywide vector control strategies. To bridge this knowledge gap requires consistent and longitudinal measurement of Aedes abundance across the city [13] as well as examination of relationships between variables at a much finer scale.

As an island city-state lying 1° north of the equator, Singapore faces regular dengue outbreaks with the four dengue virus serotypes co-circulating all year round [14]. The low herd immunity [15], coupled with the tropical climate and highly urbanized environment, poses challenges to the nation’s dengue control program [16]. As part of Singapore’s vector control program, the National Environment Agency has conducted regular inspections of homes and surrounding areas all year round to remove mosquito-breeding habitats and mobilized the community and stakeholders to minimize instances of stagnant water [17]. Vector control activities were also ramped up in dengue cluster areas, with space sprays used for adulticiding. To monitor the spatio-temporal trend of the adult Aedes abundance in Singapore, the National Environment Agency also established an islandwide Gravitrap surveillance system in 2017, with over 50,000 Gravitraps deployed in the public housing estates across the island [18, 19], which accommodate ~ 80% of the resident population [20]. The weekly mean catch per trap for each species provides an indication of the Aedes abundance around each specific residential location and each time point, which is presumed to be closely associated with an individual’s risk of exposure to mosquito bites inside or around homes and also much less susceptible to the measurement bias encountered in non-systematic breeding sites inspection [21]. To facilitate resource planning for Singapore’s vector control, we used the longitudinal dataset generated from the islandwide Gravitrap surveillance system during 2017–2018 as well as a wide range of environmental and anthropogenic variables acquired from various sources to (1) explain the spatio-temporal dynamics of the Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus population in Singapore’s high-rise residential zones and (2) assess our model’s ability to predict Aedes abundance across space and generate forecasts up to 3 weeks ahead.

Methods

Data

Aedes mosquito data were collected fortnightly for each of the 552 sites from 2017–2018 [19], with odd-numbered blocks inspected 1 week and even-numbered blocks the next. Fortnightly collections were then halved to obtain the weekly numbers of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus caught at each site respectively, which contained roughly equal numbers of odd- and even-numbered blocks. We created a 300-m buffer around each block based on Liew et al. [5], and for each site, all buffers were merged into a single polygon to be used for deriving zonal statistics for the environmental and anthropogenic variables.

The Singapore land classification map was generated at a resolution of 10 m using seven separate images from the Sentinel-2 satellite of the European Space Agency [22]. The collected images were taken on different dates to ensure the existence of cloud-free pixels for the whole of mainland Singapore based on a cloud cover classification algorithm [22]. With 309 labeled data points obtained manually using Google Earth, a random forest algorithm was used to produce seven land cover maps, excluding cloudy areas for each of the collected images [22]. The final classified land cover for each pixel was set to be the majority vote out of all the predictions, with an out-of-bag classification accuracy of 81% [22]. For each site, we derived the percentage of the buffer area covered by water, grass, forest, and managed vegetation (i.e. trees and shrubs with structure dominated by human management), respectively, setting “urban” as the reference level.

Data on waterbodies were extracted from OpenStreetMap [23]. We measured the distance to the nearest waterway from each block using ArcMap 10.6, which was then averaged within each site (similarly to the distance to the nearest water area). We also obtained Singapore’s drain line map from the Public Utilities Board. The total drain line density for each site was defined to be the total length of the drain lines falling within the corresponding buffer divided by the buffer area. In addition, the average age of buildings for each site was computed using lease commencement year data collected from the Singapore Land Authority [24].

Weekly mean, maximum, and minimum temperature and mean relative humidity were obtained from a total of 21 weather stations installed by the National Environment Agency. For each climatic variable and each week, we fitted a thin plate spline surface to produce an interpolated value for each site. Weekly raster maps of total precipitation were obtained from the Meteorological Service Singapore at ~ 500 m × 500 m resolution, and for each site and each week, all the pixel values within the corresponding buffer were averaged. All the aforementioned explanatory variables were standardized to zero mean and unit variance, and a quadratic term for each of the standardized temperature variables was created to examine nonlinear effects [25].

Statistical analyses

To understand the direction and strength of associations between Aedes abundance and different environmental and anthropogenic variables, we first computed the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients for the full set of covariates and removed redundant variables using a threshold of ± 0.6 to avoid collinearity. A Bayesian spatio-temporal model was created, where we assumed that the number of Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus caught at site \(i\) during week \(t\) (\(y_{it}\)) followed a negative binomial distribution with mean \(\mu_{it}\) and dispersion parameter \(r\), namely:

where

In the equation above, \(E_{it}\) denotes the number of Gravitraps present at site \(i\) during week \(t\), \(b_{0}\) the intercept, \(x_{ij}\) the spatial variables of site \(i\), and \(w_{itk}\) all the weekly weather measurements of site \(i\) between 1 and 3 weeks prior to week \(t\). We included an unstructured spatial effect \(u_{i}\) for each site and an extra term \(v_{{PA_{i} }}\) for the corresponding planning area (each containing 20 sites on average, with an interquartile range of 8–26) to account for additional spatial dependence. The temporally structured effect \(\phi_{t}\) was assumed to follow a random walk with a maximum order of two. Throughout this article, we used \(t = 1\) to denote the first epidemiological week of 2017 and \(t = 104\) the last epidemiological week of 2018. All the model parameters were assigned a minimally informative prior (refer to Table 2 caption), and parameter estimation was performed using Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation [26, 27], with 95% credible intervals (CrI) computed to summarize the uncertainty in each model parameter.

For each species, both the optimal order of the random walk for the temporally structured effect and the time lag of the weather variables were selected based on the deviance information criterion. Further variable subset selection was not implemented at this stage to avoid biased parameter estimates resulting from sequential comparisons, since the primary aim of our Bayesian spatio-temporal model was to infer the associations between Aedes abundance and all the different environmental and anthropogenic variables considered in this study.

Next, we used cross-validation to assess how accurately one can predict Aedes abundance across space. Here we treated the total number of Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus caught at each site during 2017–2018 as the response variable, with the log transformation of the total number of trap-week units as an offset. Only spatial fixed effects and the planning area random effect were included in the model, and a backwards elimination procedure was implemented for fixed effects variable selection using the Akaike information criterion during model training. Two forms of cross-validations were performed, namely, leave-one-site-out and leave-one-planning-area-out, where in each case a baseline prediction of the mean catch per trap per week was generated for each site, to be used as a benchmark to assess whether the model can indeed yield a higher prediction accuracy. In the former case, each time a site \(i\) was left out for testing, its baseline prediction was defined as the observed mean catch per trap per week of the site that was geographically the closest to site \(i\). In the latter case, the baseline prediction for each site \(i\) was defined as the observed mean catch per trap per week averaged across all the sites within the planning area that was geographically the closest to site \(i\) but did not contain site \(i\).

Finally, we evaluated the contribution of weather variables to the improvement of the weekly Aedes abundance forecast accuracy up to 3 weeks ahead. Using \(t_{C}\) to denote the current time point, we treated the mean catch per trap of each site at week \(\left( {t_{C} + \Delta t} \right) \left( {\Delta t = 1,2, {\text{or }} 3} \right)\) as the response variable, and each was regressed upon all the weather and/or entomological (i.e. Aedes abundance) covariates at weeks \(t_{C}\), \(\left( {t_{C} - 1} \right)\) and \(\left( {t_{C} - 2} \right)\). Here, the entomological covariates were always included as autoregressive terms, with the additional inclusion of weather covariates in an alternative model to assess the resulting change in the out-of-sample forecast errors. Due to the large number of lagged weather variables included in the alternative model, we used the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator to perform variable selection during model training. For each site and each species, we derived the out-of-sample Aedes abundance forecast accuracy at week \(\left( {t^{*} + \Delta t} \right)\) for all combinations of \(t^{*} \in \left\{ {55, 60, \ldots , 95, 100} \right\}\) and \(\Delta t \in \left\{ {1,2,3} \right\}\), respectively, with the model being trained on all the historical data points of that site with \(t_{C} < t^{*}\). The corresponding baseline forecast was defined as the observed Aedes abundance of that site at week \(t^{*}\), and hence we will also refer to \(t^{*}\) as the baseline time point.

Results

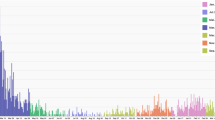

In total, 4,923,456 trap-week units of observation were obtained, with 495,638 Ae. aegypti and 132,533 Ae. albopictus caught during the entire study period. For both species, we observed a marked difference in the Aedes abundance across space, with the mean catch per trap per week at some sites exceeding fivefold that at some other sites (Fig. 1). For example, only an average of 0.05 Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were caught per trap per week at a site within the Clementi area during the study period, in contrast to 0.28 at a site in Tampines. Operationally, these data are updated on a weekly basis to provide policy makers with an indication of which areas may require more vector control to mitigate the risk of dengue transmission. The mean and standard deviation of the site-level mean catch per trap per week were 0.102 and 0.074 for Ae. aegypti and 0.027 and 0.019 for Ae. albopictus (Table 1 contains the summary statistics of all the variables in this study, and visualizations of selected variables across space or time can be found in Additional file 1: Supporting information).

Observed Aedes abundance (mean catch per trap per week) of each site during 2017–2018: (a) Ae. aegypti and (b) Ae. albopictus. We first created a 300 m buffer around each block, and all buffers for each site were merged into a single polygon, which was then colored according to the observed Aedes abundance value

Based on the spatio-temporal model estimates, both nearby managed vegetation cover and building age were found to have a direct association with the abundance of both species (Table 2 and Fig. 2). On average, we estimated that a 1-SD (10 years) increase in the average age of buildings was associated with a 52.3% (95% CrI: 42.0%–63.2%) increase in the Ae. aegypti abundance and a 38.1% (95% CrI: 31.0%–45.6%) increase in the Ae. albopictus abundance at the site level, when all the other variables were held constant (Fig. 2). For forest cover and distance to water area, the signs of the point estimates were found to be opposite between the two mosquito species, although the 95% credible interval may contain the null effect in some cases (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Even after controlling for all the fixed effects, substantial heterogeneity of Aedes abundance remained both between sites and between planning areas, as shown by the standard deviation estimates of the spatial random effects (Table 2).

Estimated percentage change in the expected value of Aedes abundance (weekly mean catch per trap) due to a 1-SD increase in each covariate when all the other variables were held constant. Filled circles denote the posterior median estimates, and the solid lines denote the 95% credible intervals. The standard deviation of each covariate can be found in Table 1, and the estimated effects of lagged temperature covariates on the predicted Aedes abundance were visualized in Fig. 3

For both species, inclusion of weather measurements in all the past 3 weeks together with a random walk model of order 2 for the temporally structured effect yielded the lowest deviance information criterion. However, compared with the spatial covariates, the weather covariates were estimated to have a relatively limited impact on the variation of adult Aedes abundance in the context of Singapore (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The 95% credible intervals of the quadratic term coefficients for the weekly maximum temperature were away from zero for both species and all time lags (Table 2), and the Aedes abundance was estimated to first increase and then decrease as we varied the lagged weekly maximum temperature from 28.0 °C to 36.6 °C while holding the other variables constant (Fig. 3). Specifically, with all other covariates held constant, the median estimate of Ae. aegypti abundance peaked at 30.3 °C, 30.0 °C, and 31.3 °C for weekly maximum temperature measured at 1, 2, and 3 weeks’ lag, respectively. Similarly, the turning points were 31.9 °C, 31.6 °C, and 31.9 °C for Ae. albopictus. Out of all the covariates collected in this study, only weekly mean and minimum temperatures were removed from the Bayesian spatio-temporal model during collinearity assessment.

In both leave-one-site-out and leave-one-planning-area-out cross validations, which were performed to assess predictive accuracy across space, there was an overall increasing trend in the observed site-level Aedes abundance as we moved from the lowest to the highest quintile based on the out-of-sample model predictions (Fig. 4). Except for the leave-one-site-out cross validation of the model for Ae. aegypti, there was a modest and statistically significant reduction in the mean absolute prediction error of the model compared with the baseline prediction (Table 3). Likewise, a modest and statistically significant reduction in the out-of-sample forecast error was observed for models forecasting 2- or 3-week ahead Aedes abundance, regardless of species or whether we included weather covariates as additional predictors (Table 4). Our model, however, did not outperform the 1-week ahead baseline forecast (Table 4), owing to the fortnightly mosquito collection and the subsequent conversion to weekly data (details described in Methods), which caused data points at adjacent weeks to share 50% of the information in common. Notably, we found that in all cases the additional inclusion of lagged weather covariates did not improve the out-of-sample forecast accuracy compared with a simple model that only included autoregressive terms as predictors (Table 4).

Box-plots of the observed site-level Aedes abundance (mean catch per trap per week) during 2017–2018 within each quintile based on the out-of-sample model predictions: (a), (b) leave-one-site-out cross validation and (c), (d) leave-one-planning-area-out cross validation. A small number of extreme values were omitted from the graph for clarity

Discussion

This study examined the spatial and temporal variation of the main dengue vectors in Singapore’s high-rise public residential zones in relation to a wide range of environmental and anthropogenic variables. The insights derived from this study further add to previous work that aimed to understand Aedes ecology in the local context and can facilitate the formulation of more effective vector control strategies in the future. Our model performance also suggests the potential use of spatio-temporal mapping as a tool to improve the understanding of the Aedes distribution in other cities or countries, where intensive entomological surveillance may be harder to achieve.

We found that the majority of our spatial covariates had an at least borderline significant association with the Aedes abundance (i.e. the 95% credible intervals did not/barely overlap zero). In particular, building age was shown to be the strongest predictor. This might be due to a combination of factors, including infrastructural degradation and the water storing practices associated with the sociodemographic profile of residents that result in more instances of water stagnation that can breed mosquitoes. For both species, we estimated that an increase in the managed vegetation cover within the buffer area was associated with a substantial rise in the mean vector abundance, likely owing to the increased availability of water in leaf axils, leaf litter, and discarded receptacles hidden in foliage and tree holes, which supports mosquito breeding. Unlike managed vegetation cover, both forest and grass covers were found to be negatively associated with the abundance of Ae. aegypti. This was not unexpected given that Ae. aegypti prefers highly urbanized areas where it can breed in artificial containers. On the other hand, there was a positive association between forest cover and Ae. albopictus abundance based on the point estimate, which is consistent with the existing knowledge of the vector’s ecology [28].

Our analysis showed a borderline significant negative association between drain line density and the abundance of Ae. aegypti in contrast to the positive correlation reported by Seidahmed et al. [29]. This discrepancy can be due to a number of reasons: for example, the study conducted by Seidahmed et al. was restricted to a small area of Singapore, and results may be confounded by the different housing types with different demography [29], whereas this study used 2-year data collected from the same type of housing areas across the island. Moreover, the number of Aedes mosquitoes caught inside the high-rise residential buildings and the number of outdoor breeding habitats can be impacted by drain line density in different ways. Since perimeter drains are known to be the most common breeding habitats of Aedes in Singapore’s public areas according to routine inspections [30], their abundance could simultaneously decrease the per-mosquito probability of looking for oviposition sites inside residential buildings and increase the total number of Aedes mosquitoes in the nearby public area. Thus, our estimate is likely to be a reflection of the resulting net effect and similarly for the estimated effects of other spatial covariates such as nearby managed vegetation cover.

Previous work has highlighted the challenges of mapping the spatial distribution of Aedes mosquitoes for operational dengue vector control [31]. In particular, predictors that can be informative across an entire continent or a sufficiently large country may lose predictive power within the confines of a single city [31]. While we did observe substantial evidence of a non-zero association between many spatial covariates and Aedes abundance in our analysis, the estimated standard deviations of the spatial random effects remained large, suggesting substantial unexplained heterogeneity across space. Hence, entomological surveillance remains critical to generating knowledge of Aedes abundance in the field to inform vector control. On the other hand, we found that in most cases the model performed significantly better than the baseline at predicting mosquito abundance at new locations, based on the spatial variables at those locations, suggesting that statistical modeling can still serve as a complementary tool to refine our understanding of the Aedes abundance at locations where entomological data are unavailable and hence to identify additional locations that may require enhanced vector control. It should be noted that the model’s improvement in prediction accuracy over the baseline was found to be smaller for Ae. aegypti than Ae. albopictus, despite the former being the most important dengue vector in Singapore. This finding may be explained by the ecology of Ae. aegypti, which is a container breeder that is subject to the vagaries of human behavior; adherence to household practices to prevent breeding is hard to measure and may vary spatially, rendering spatial modeling much more challenging.

There is abundant literature on how different weather variables regulate the population dynamics of Aedes via influencing mosquito habitat availability, development, survival, and reproduction [9]. In this study, however, we estimated the effects of all the lagged weather variables on the observed Aedes abundance to be very minimal, which can be owing to the restricted range of the weather variables in the context of Singapore as well as vector control activities that were typically ramped up during higher breeding seasons. The assessment of the out-of-sample forecast errors, too, shows that the additional inclusion of weather covariates did not improve the accuracy of the Aedes abundance forecasts, and a simple model with autoregressive terms alone could yield a modest and statistically significant improvement in the 2- and 3-week-ahead forecasts over the baseline. While these results may suggest that weather had a negligible impact on Aedes abundance in Singapore, it should be noted that this study was conducted in public housing estates and detected mosquitoes that may have hatched nearby, and the relationship between weather and outdoor breeding habitats may be more complex than was identified herein. A longitudinal entomological study in the Geylang neighborhood of Singapore found that the outdoor Aedes population was likely to be shaped by rainfall through a monsoon-driven sequence of flushing, drying and return of breeding habitats [32]. Taken together, these results suggest the differential impacts of weather on the Aedes population dynamics and hence the potential risk of exposure to mosquito bites in different settings, i.e. Aedes abundance inside and nearby public housing estates may be less sensitive to changes in weather compared with outdoor abundance.

Our results need to be interpreted in the light of the following limitations. First, we were unable to account for the effects of vector control programs on the observed Aedes abundance across space and time. Regulatory inspections and community efforts aimed at removing larval habitats, as well as chemical control to reduce adult mosquito populations, usually peak during higher vector breeding/dengue transmission seasons, and this could to some extent mask the true association between different weather variables and the Aedes abundance, with the confounding bias difficult to quantify or adjust for. Besides, there could be a residual spatial dependence structure in our data due to factors such as potential ongoing expansion of Aedes mosquitoes, which may have been coincidentally absorbed by certain spatial covariates because of confounding. Nonetheless, this issue was assessed via a leave-one-planning-area-out cross-validation framework with baseline predictions created to serve as a benchmark for model performance comparison, and results suggest that the spatial covariates could indeed enhance the out-of-sample predictive accuracy. In addition, our parameter estimates were derived based on mosquito data collected from Singapore’s high-rise public residential zones and thus should not be used for extrapolation to low-rise houses. Previous work has suggested that the risks of indoor breeding of Aedes mosquitoes could be highly dependent on the accommodation type in Singapore [29]. In early 2020, the National Environment Agency extended the deployment of Gravitraps to private landed residential estates [33], and as more data are being generated, this will shed further light on how Aedes abundance differs between high- and low-rise residential zones across the island.

Conclusions

Our study has demonstrated the potential and challenges of spatio-temporal modeling for improving the understanding of the main dengue vectors’ ecology and provided empirical evidence to guide the refinement of vector control strategies in the context of Singapore. Our findings suggest that public residential estates with older buildings and more nearby managed vegetation should be prioritized for vector control inspections and community advocacy to reduce the abundance of Aedes mosquitoes and the risk of dengue transmission. The insights obtained from this study could also be helpful to inspire future studies that attempt to understand the spatio-temporal dynamics of the dengue vector population at a city scale, particularly in settings where entomological surveillance data are less abundant and thus require modeling to further narrow the knowledge gap.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the National Environment Agency or Singapore-ETH Centre.

References

World Health Organization (2009) Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control. WHO/HTM/NTD/DEN/20091.

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–7.

World Health Organization (2018) Questions and Answers on Dengue Vaccines. In: Immunization, Vaccines Biol. https://www.who.int/immunization/research/development/dengue_q_and_a/en/. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

Fitzpatrick C, Haines A, Bangert M, Farlow A, Hemingway J, Velayudhan R. An economic evaluation of vector control in the age of a dengue vaccine. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:1–27.

Liew C, Curtis CF, Agency NE, Liew C, Curtis CF. Horizontal and vertical dispersal of dengue vector mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, in Singapore. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:351–60.

Brady OJ, Hay SI (2020) The Global Expansion of Dengue: How Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes Enabled the First Pandemic Arbovirus. Annu Rev Entomol 65:annurev-ento-011019-024918.

Brady OJ, Golding N, Pigott DM, Kraemer MUG, Messina JP, Reiner Jr RC, Scott TW, Smith DL, Gething PW, Hay SI (2014) Global temperature constraints on Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus persistence and competence for dengue virus transmission. Parasit Vectors 7:338.

Vanwambeke SO, Somboon P, Harbach RE, Isenstadt M, Lambin EF, Walton C, Butlin RK. Landscape and land cover factors influence the presence of Aedes and Anopheles Larvae. J Med Entomol. 2007;44:133–44.

Morin CW, Comrie AC, Ernst K. Climate and Dengue Transmission: evidence and Implications. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:1264–72.

Kraemer MUG, Sinka ME, Duda KA, et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. Albopictus. Elife. 2015;4:1–18.

Dickens BL, Sun H, Jit M, Cook AR, Carrasco LR (2018) Determining environmental and anthropogenic factors which explain the global distribution of Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. BMJ Glob Heal 3:e000801.

Kraemer MUG, Reiner RC, Brady OJ, et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:854–63.

Reiner RC, Stoddard ST, Vazquez-Prokopec GM, et al. Estimating the impact of city-wide Aedes aegypti population control: an observational study in Iquitos Peru. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007255.

Lee KS, Lo S, Tan SSY, Chua R, Tan LK, Xu H, Ng LC. Dengue virus surveillance in Singapore reveals high viral diversity through multiple introductions and in situ evolution. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:77–85.

Tan LK, Low SL, Sun H, et al. Force of infection and true infection rate of dengue in singapore: implications for dengue control and management. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188:1529–38.

Lee C, Vythilingam I, Chong CS, Abdul Razak MA, Tan CH, Liew C, Pok KY, Ng LC. Gravitraps for management of dengue clusters in Singapore. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:888–92.

Sim S, Ng LC, Lindsay SW, Wilson AL. A greener vision for vector control: the example of the Singapore dengue control programme. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008428.

National Envronmental Agency (2019) NEA Urges Continued Vigilance In Fight Against Dengue. https://www.nea.gov.sg/media/news/news/index/nea-urges-continued-vigilance-in-fight-against-dengue-2019. Accessed 14 Oct 2019.

Ong J, Chong C-S, Yap G, Lee C, Abdul Razak MA, Chiang S, Ng L-C. Gravitrap Deployment for Adult Aedes aegypti Surveillance and its Impact on Dengue Cases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008528.

Govtech (2020) Data.gov.sg. https://data.gov.sg/. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

Ong J, Liu X, Rajarethinam J, Yap G, Ho D, Ng LC. A novel entomological index, Aedes aegypti Breeding Percentage, reveals the geographical spread of the dengue vector in Singapore and serves as a spatial risk indicator for dengue. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:17.

Richards DR, Tunçer B. Using image recognition to automate assessment of cultural ecosystem services from social media photographs. Ecosyst Serv. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOSER.2017.09.004.

OpenStreetMap. https://www.openstreetmap.org.

Housing & Development Board Resale Flat Prices. https://services2.hdb.gov.sg/webapp/BB33RTIS/BB33PReslTrans.jsp. Accessed 11 Sep 2017.

Brady OJ, Johansson MA, Guerra CA, et al. Modelling adult Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus survival at different temperatures in laboratory and field settings. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:351.

Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 2009;71:319–92.

The R-INLA project. www.r-inla.org.

World Health Organization Dengue control-The mosquito. https://www.who.int/denguecontrol/mosquito/en/. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

Seidahmed OME, Lu D, Chong CS, Ng LC, Eltahir EAB. Patterns of urban housing shape dengue distribution in singapore at neighborhood and country scales. GeoHealth. 2018;2:54–67.

National Environment Agency (2019) Know The Potential Aedes Breeding Sites. https://www.nea.gov.sg/dengue-zika/prevent-aedes-mosquito-breeding/know-the-potential-aedes-breeding-sites. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

Eisen L, Lozano-Fuentes S. Use of Mapping and Spatial and Space-Time Modeling Approaches in Operational Control of Aedes aegypti and Dengue. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e411.

Seidahmed OME, Eltahir EAB (2016) A Sequence of Flushing and Drying of Breeding Habitats of Aedes aegypti (L.) Prior to the Low Dengue Season in Singapore. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004842.

National Environment Agency (2020) NEA Vox. https://www.nea.gov.sg/media/nea-vox/index/why-is-nea-placing-mosquito-traps-outside-my-house-will-this-increase-my-chances-of-being-bitten-by-mosquitoes#.XPTELvi-F3o. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following people who have contributed to this study: Staff of Environmental Public Health Department involved in mosquito surveillance and operations, Dr. Chee-Seng Chong and team for their technical assistance, and Lynette Tay for her assistance in data acquisition.

Funding

ARC and BLD are supported by the National Medical Research Council through the Singapore Population Health Improvement Centre (NMRC/CG/C026/2017_NUHS). LRC is supported by the CDPHRG grant (CDPHRG14NOV007). The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LRC, ARC, LCN, BLD, and HS conceptualized and designed the study. HS, BLD, DR, JO, JR, and MH contributed to data collection/acquisition and processing. HS carried out the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BLD and JTL contributed to results visualization. All authors contributed to the results interpretation, revision of the manuscript, and approved it before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The permission to use the entomological data was approved by the National Environment Agency, Singapore.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, H., Dickens, B.L., Richards, D. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of the main dengue vector populations in Singapore. Parasites Vectors 14, 41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04554-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04554-9