Abstract

Background

Wildlife species carry a remarkable diversity of trypanosomes. The detection of trypanosome infection in native Australian fauna is central to understanding their diversity and host-parasite associations. The implementation of total RNA sequencing (meta-transcriptomics) in trypanosome surveillance and diagnosis provides a powerful methodological approach to better understand the host species distribution of this important group of parasites.

Methods

We implemented a meta-transcriptomic approach to detect trypanosomes in a variety of tissues (brain, liver, lung, skin, gonads) sampled from native Australian wildlife, comprising four marsupials (koala, Phascolarctos cinereus; southern brown bandicoot, Isoodon obesulus; swamp wallaby, Wallabia bicolor; bare-nosed wombat, Vombatus ursinus), one bird (regent honeyeater, Anthochaera phrygia) and one amphibian (eastern dwarf tree frog, Litoria fallax). Samples corresponded to both clinically healthy and diseased individuals. Sequencing reads were de novo assembled into contigs and annotated. The evolutionary relationships among the trypanosomatid sequences identified were determined through phylogenetic analysis of 18S rRNA sequences.

Results

We detected trypanosome sequences in all six species of vertebrates sampled, with positive samples in multiple organs and tissues confirmed by PCR. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the trypanosomes infecting marsupials were related to those previously detected in placental and marsupial mammals, while the trypanosome in the regent honeyeater grouped with avian trypanosomes. In contrast, we provide the first evidence for a trypanosome in the eastern dwarf tree frog that was phylogenetically distinct from those described in other amphibians.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-transcriptomic analysis of trypanosomes in native Australian wildlife, expanding the known genetic diversity of these important parasites. We demonstrated that RNA sequencing is sufficiently sensitive to detect low numbers of Trypanosoma transcripts and from diverse hosts and tissues types, thereby representing an effective means to detect trypanosomes that are divergent in genome sequence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Trypanosomes are haemoprotozoan parasites that infect a wide range of animal taxa [1,2,3]. Endemic Australian fauna is a susceptible target for trypanosome infection, and several studies have revealed a remarkable diversity of trypanosomes in Australian wildlife [3,4,5,6,7]. This includes more than 15 species of exotic and endemic trypanosomes as well as several unclassified species [7, 8]. While some Trypanosoma species are associated with serious disease [9, 10], others play an undetermined role in the health of their hosts. For instance, the native trypanosomes Trypanosoma copemani and T. vegrandis have been associated with population declines of woylies (Bettongia penicillata) in Western Australia (WA) [9, 10]. It is likely that a similar phenomenon extends to other marsupial species, highlighting the need for continued surveillance [8, 11].

To date, most trypanosome surveillance has been directed toward screening Australian mammals (i.e. bats, marsupials, monotremes, and rodents). Marsupials, in particular, have been widely screened, allowing the identification of several trypanosome species (e.g. T. copemani, T. irwini and T. gilletti) [7, 11,12,13]. However, trypanosome infection has also been detected in other Australian vertebrate wildlife such as amphibians, birds, fish and reptiles [8, 14, 15]. Moreover, trypanosomes have been detected in hematophagous invertebrates that become infected while feeding on infected vertebrate hosts and which may act as parasite vectors [16, 17]. For example, in Australia, trypanosomes have been found in both aquatic leeches and ticks [5, 18, 19]. Other invertebrates such as lice, culicid mosquitoes, sand-flies, and tabanid flies are also believed to be potential trypanosome vectors [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. However, because incidental infection during feeding is not necessarily associated with vector competence, further research is needed to determine the role of these hematophagous invertebrates in trypanosome transmission [8, 18].

Multiple trypanosome species have been documented in Australian wildlife. For example, surveillance in marsupials recorded up to five species (T. irwini, T. gilletti, T. copemani, T. vegrandis and T. noyesi) in koalas [4], with similar results in woylies and the southern brown bandicoot [9, 12]. In addition, the monitoring of Australian mammals has shown that Trypanosoma spp. are present in animals sampled on the east and west coasts of Australia, as well as Tasmania [7]. Despite this, there are clear gaps in sampling, and it is likely that trypanosomes are widespread across the Australian continent and in mammalian species [7].

Diagnosis of trypanosome infection largely relies on microscopy and a variety of molecular techniques [27]. PCR-based Sanger sequencing of genetic markers constitutes the gold standard for molecular diagnosis, including the 18S rRNA gene in the small subunit rRNA (SSU), and the region encoding the glycosomal glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (gGAPDH), an enzyme involved in the glycolytic pathway [28]. In recent years, a number of studies have implemented amplicon-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) to reveal the genetic diversity of trypanosomes in Australian marsupials [4, 6]. In comparison with conventional methods, NGS enables detection of trypanosome sequences at low copy number and target multiple genes with both high-throughput and accuracy. In addition, the development of meta-transcriptomics (i.e. bulk RNA sequencing) has enabled the detection and quantification of the transcripts expressed in the intra- and extracellular environments, including those derived from trypanosomes and other pathogens [29], and hence represents an increasingly valuable diagnostic tool [30,31,32].

Herein, we employed, for the first-time, a meta-transcriptomics approach as a method for the identification and surveillance of Trypanosoma in wildlife, screening different tissues from a variety of native Australian species. From this, we identified trypanosomes in several vertebrate groups from New South Wales (NSW) and Tasmania (TAS), including the identification of a divergent species of Trypanosoma in an amphibian species.

Methods

Sample collection

Most samples in this study were collected by the Australian Registry for Wildlife Health (ARWH) during monitoring surveys of wildlife, as well as from road-kill cases in NSW. The bare-nosed wombats were derived from road-kill in southern Tasmania. Following dissection, all tissue samples were stored at -80 °C until molecular analysis (Table 1). In total, we analysed 17 samples from different Australian native animal species, including four marsupials (koala, Phascolarctos cinereus; southern brown bandicoot, Isoodon obesulus; swamp wallaby, Wallabia bicolor; bare-nosed wombat, Vombatus ursinus), one bird (regent honeyeater, Anthochaera phrygia) and one amphibian (eastern dwarf tree frog, Litoria fallax). The amphibian specimen corresponded to a male diagnosed with severe, multisystemic, chronic trypanosomiasis (Additional file 1: Figure S1) and presumptive testicular Myxobolus-like infection. All individuals were identified to the lowest taxonomic level. Our sample set contained both healthy and diseased individuals (Table 1).

Sample processing

In brief, total RNA was extracted from a variety of sample tissues (Table 1) using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing libraries were generated using the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Preparation protocol (Illumina) with host ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion (RiboZero Gold – Epidemiology). Subsequently, paired-end (100 bp) sequencing of the cDNA libraries was performed using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 system targeting at least 20M paired reads per library. All library preparation and sequencing were carried out by the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF).

Meta-transcriptomic analysis

Sequence reads were trimmed for quality using the Trimmomatic tool [33] and assembled de novo into contigs using Trinity v. 2.5.1 [34] with default parameter settings. The relative abundance of transcripts was quantified as the number of transcripts per kilobase million (TPM). In short, this metric normalizes transcript abundance by transcript length and sequencing depth. For sequence identification, particularly of trypanosomes, the assembled contigs were compared against the NCBI GenBank nucleotide (nt) and non-redundant protein (nr) databases using BLASTN and DIAMOND v.0.9.32 [35] (Additional file 2: Table S1). Those contigs that exhibited matches to known trypanosome sequences with an e-value > 1 × 10−70 were retained for downstream analyses. Further, contigs corresponding to the stably expressed host mitochondrial marker, cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1), were identified based on sequence alignments using DIAMOND. All contigs were aligned to reference sequences using BBMap v.37.98 and cross-validated to DIAMOND results to verify that the matches correspond to the vertebrate host. Abundance was quantified as the sum of relative abundances of contigs for the marker. Sequence contigs were annotated as follows: (i) to find conserved domains and classify protein families, sequences were compared against the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) [36] and InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/); (ii) for gene assignment, all putative trypanosome contigs were aligned against a custom reference sequence database (genome assembly ASM21029v1) using DIAMOND [35].

Confirmatory PCR

All samples included in this study were screened for Trypanosoma infection via PCR assays using primers targeting 2136-bp (outer) and 320-bp (nested) fragments of the 18S rRNA (Additional file 3: Table S2). In general, the cDNA was synthesised from up to 100 ng of total RNA using random hexamers and SuperScript™ VILO™ (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The RT-PCR reactions proceeded as follows: 10 min of random priming at 25 °C, 20 min of extension at 50 °C, and 5 min of RT denaturation at 85 °C. Similarly, the PCR reactions with Platinum™ SuperFi™ (Invitrogen) were performed as follows: 1 min of hot start at 98 °C, followed by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, primer annealing for 10 s, and then extension at 72 °C according to conditions described in Additional file 3: Table S2. A final elongation step was run at 72 °C for 1 min. PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Controls were included to identify potential cross-contamination in reagents.

Phylogenetic analysis

The trypanosome contigs obtained here were compared with homologous sequences retrieved from GenBank, using 18S rRNA as a key phylogenetic marker (Additional file 4: Table S3). Multiple sequence alignment (n = 81) was conducted using the E-INS-i algorithm in MAFFT v7.450. The best-fit model of nucleotide substitution (i.e. GTR+F+I+Γ4) was determined by using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) in the ModelFinder program [37] implemented in IQ-TREE v1.6.7 [38]. Phylogenetic relationships were then inferred using the maximum likelihood method [39] available in IQ-TREE v1.6.7 [38]. Nodal support values were also assessed by using a SH-like approximate Likelihood Ratio Test (SH-aLRT) and 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot) replicates [40].

Results

Detection of Trypanosoma in screened samples

Using a meta-transcriptomic approach, we successfully identified trypanosome transcripts in six Australian species sampled in NSW and TAS, corresponding to the animal classes Amphibia, Aves and Mammalia. Trypanosome transcripts were detected in 60% (3 out of 5) of bare-nosed wombats, 71.43% (5 out of 7) of koalas, in both of the swamp wallaby samples, reagent honeyeater (n = 1), southern brown bandicoot tail (n = 1), and the eastern dwarf tree frog (n = 1). In total, trypanosomes were detected in 76.47% (13/17) of the individuals screened. With respect to target tissues, we detected trypanosome transcripts across a variety of tissues in infected individuals (Table 1), and positive samples were collected from both apparently healthy and diseased individual animals.

Despite the widespread presence of Trypanosoma in the samples characterized, we observed marked variation in the abundance and number of de novo assembled contigs among libraries. In general, the host cox1 transcripts were ~ 60% to ~ 99% more abundant than trypanosome transcripts (Table 2). Since samples showing high abundance of host cox1 also exhibited variable levels of abundance for trypanosome transcripts, these results suggest that the variation in abundance levels among samples was not due to biases in sampling processing. In addition, most transcripts were detected in the swamp wallaby #2 sample (n = 314, i.e. 0.05% of total transcripts per library) followed by the eastern dwarf tree frog (n = 149, i.e. 0.03% of total transcripts per library), whereas the lowest number of transcripts was identified in the regent honeyeater (n = 3, i.e. 0.0008% of total transcripts per library) (Table 3; Additional file 2: Table S1). Top BLAST hits ranged from 241 bp to 2258 bp, targeting regions corresponding to the transcribed spacers (ITS1, ITS2) and the 5.8S rRNA, 18S rRNA and 28S rRNA of the large subunit of the ribosome. Similarly, we recovered hits against uncharacterized proteins, the surface protease GP63, and the heat shock proteins (HSPs) of Trypanosoma.

To place trypanosome sequences into a phylogenetic context (see below), and hence achieve taxonomic assignment, we identified the contigs targeting the 18S rRNA of the SSU. Abundance levels of 18S rRNA contigs ranged from 0.64 to 743.40 TPM. The highest cumulative abundances were identified in the eastern dwarf tree frog (TPM = 46.71) and the swamp wallaby #2 (TPM = 802) (Table 2), while the Southern brown bandicoot showed the lowest values (TPM = 0.64). In comparison, the host reference gene cox1 was abundantly expressed across samples (TPM: 512.02–30,192.26), with the highest levels observed in the swamp wallaby #1 sample (TPM = 30,192.26).

To validate these results, we used PCR assays and generic primers targeting the 18S rRNA gene (Additional file 3: Table S2) to detect trypanosome infection in all samples analyzed. Samples comprised a number of organs and tissues, including brain (n = 1), ear (n = 1), liver (n = 14), lung (n = 1), tail (n = 1), and testes (n = 1). A 320-bp nested fragment corresponding to the 18S rRNA was amplified in all samples containing trypanosomes, as previously identified by meta-transcriptomics (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analysis of Trypanosoma-positive samples

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that trypanosomes infecting the Australian native species covered in our study were generally closely related to known trypanosome species (Fig. 1). We identified trypanosome sequences in the specimens of the swamp wallaby that fell into two separate clades associated with placental and marsupial mammals. However, most samples grouped with different trypanosomes identified from marsupials, forming a group that we term the “Marsupialia” clade (Fig. 1). This clade can be further divided into two groups: the first includes trypanosomes from the wallaby and the southern brown bandicoot, while the second group contained trypanosomes from the wallaby and bare-nosed wombat. Strikingly, the trypanosome from the koala fell into a different clade that is related to T. gennarii (nucleotide sequence similarity of 81.30%) and T. freitassi (82.04%) identified in South American marsupials (Monodelphis spp.), T. bennetti (92.56%) in birds (Falco sparverius) and T. irwini (98.75%) in koalas. Moreover, we identified a trypanosome species in the regent honeyeater that is closely related to the avian trypanosomes T. thomasbancrofti and T. avium that share ~100% and 97% sequence similarity, respectively. Sequence comparisons against avian genotypes 1–4 (classification sensu Šlapeta et al. (2016) [41]) showed a perfect match with genotype 1 of T. thomasbancrofti (Additional file 5: Table S4), indicating that the regent honeyeater trypanosome likely belongs to that species.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary relationships among trypanosomes sampled here (branch labels in bold) and background representative sequences. Branch tips are colored according to the host of sampling. Trypanosomes detected in fish and annelids are indicated by a star. Animal silhouettes represent the hosts that tested positive for trypanosome infection. Node support values (SH-aLRT > 80% and UFBoot > 95%) are indicated with white circle node shapes in the tree. Trypanosoma sp. ABF was also identified in a specimen from NSW

In addition to the trypanosomes related to mammals and birds, we identified a trypanosome species infecting the eastern dwarf tree frog that was divergent from other trypanosomes in amphibians (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Notably, this amphibian trypanosome was related to those present in other amphibians, reptile and insect species, although it fell in a phylogenetically divergent position in the clade (with relatively strong support; SH-aLRT 89.6%; UFBoot 76%) and hence represents a novel lineage. The position of the dwarf tree frog sequence remained unchanged following additional analyses including a broader range of fish, reptile and leech transcriptomes (data from ref. [16]), indicating that it is not an artefact due to biases in taxon sampling (Additional file 6: Figure S2).

Discussion

We have, to our knowledge for the first time, implemented a meta-transcriptomic approach for detecting Trypanosoma spp., investigating a variety of wildlife species indigenous to Australia. Unlike conventional methods for trypanosome diagnosis (cellular culture, PCR assays, and Sanger sequencing) [42], meta-transcriptomics represents an unbiased approach for the detection of parasite diversity within samples, only requiring sufficient levels of gene expression [29]. To date, only a few surveillance studies have applied NGS technologies for the detection of trypanosomes in wildlife, although this approach is able to identify mixed trypanosome infections in marsupials and effectively screen their ectoparasites [4, 6]. Using total RNA sequencing we identified trypanosomes in four marsupials, one bird and one amphibian species, highlighting the ability of this approach to detect parasites in a range of host species and target tissues (Table 1). Hence, meta-transcriptomics enables the detection of trypanosomes in a broad range of samples that might include symptomatic and subclinical infections, different stages of disease, as well as variable levels of parasitemia.

Most of the trypanosome transcripts identified in the hosts analyzed were associated with genes encoding ribosomal components, suggesting that ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis have a central role in the infection process (Tables 2, 3). In the case of the heat-shock protein 90 (Hsp90) identified in the eastern dwarf tree frog, the presence of this molecular chaperone has been associated with transitions across trypanosome life-cycle stages [43]. Hsp90 synthesis induction has also been related to stress responses in T. cruzi, reflecting the change in temperature when the parasite moves from the vector to the mammalian host [44, 45]. Hsp90 is also known to play an essential role in protein folding and degradation under normal conditions [46, 47]. The major surface protease GP63 identified in swamp wallaby #2 is a highly immunogenic antigen involved in macrophage-parasite interaction encoded by a multi-copy gene that also occurs in Leishmania [48, 49]. Differential expression of GP63 is associated with the parasite life-cycle, with genetic variation facilitating immune evasion and colonization [48, 50].

Previous studies have suggested that trypanosomes often have deleterious effects on the health of the infected hosts [9,10,11, 51, 52]. As the trypanosomes described here were detected in both healthy and diseased individuals, we are unable to make inferences on their capacity to cause disease (Table 1). Indeed, many of the health conditions manifest in the animals studied were unspecific or prone to be associated with other sort of infections. For instance, the pulmonary congestion and oedema in the swamp wallaby #1 sample may be consistent with orbivirus infection symptoms (family Reoviridae) [53], while the pox-like lesions in the southern brown bandicoot have been previously associated with infection by the Bandicoot papillomatosis and carcinomatosis virus (BPCV2) (Polyomaviridae) in the western barred bandicoot (Perameles bougainville) [54]. Similarly, although the ear lesions in the swamp wallaby #2 could be attributed to trypanosome infection, other causative pathogens could be associated with the lumpy jaw and emaciation [55, 56]. In addition, the eastern dwarf tree frog was co-infected with Trypanosoma and Myxobolus, confounding the association of disease with any etiological agent. Because our study was limited to vertebrates, it does not provide insights into the potential vector involved in parasite transmission. However, as suggested in previous studies, it is possible that both ticks and dipterans (i.e. flies and mosquitoes) are vectors of these parasites as they can feed on a large variety of hosts including mammals, birds and amphibians [4, 18,19,20, 22, 57, 58]. Some hemipterans might also play a vectorial role in the transmission of trypanosomes in sylvatic and peridomestic settings, as documented in the Americas [59,60,61]. Clearly, more research is needed to clarify the vectors and the mode of trypanosome transmission in Australian wildlife [8, 18, 19].

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the trypanosomes identified in native Australian fauna fell into different lineages that were largely concordant with that of the host species from which they were sampled, although we were unable to make taxonomic assignments to the species level. Notably, we identified three distinct clades of marsupial trypanosomes (Fig. 1). The trypanosome species detected in the swamp wallaby that fell outside the Marsupialia clade was closely related to Trypanosoma sp. ABF previously described in the swamp wallaby in NSW [8], and to T. cyclops, an exotic trypanosome isolated from the monkey Macaca nemestrina and related to T. theileri-related trypanosomes in ruminants and tabanids. The relatedness among these trypanosome species raises concerns over the potential susceptibility of Australian vectors and vertebrates to infection by exotic trypanosomes and hence the establishment of a zoonotic transmission cycle [7, 8]. In addition, although most marsupial trypanosomes analyzed fell into the Australian Marsupialia clade, trypanosome species infecting these mammals did not form a monophyletic group, indicative of a history of cross-species transmission [62].

Among the trypanosome species infecting marsupials, T. irwini, T. gilletti, T. copemani, T. vegrandis, T. noyesi and Trypanosoma sp. AB-2017 have been described in koalas [4, 7, 13]. Our results indicated that Trypanosoma sp. detected in the koala was closely related to T. irwini and the avian exotic trypanosome T. bennetti. Given than the former has been also identified in koalas, the trypanosome detected in the sampled koala likely corresponds to T. irwini. The close relationship between the T. irwini and T. bennetti has been previously documented [8, 13] and is compatible with the hypothesis that hosts sharing similar environments and vectors are susceptible to related parasites (i.e. “host-fitting”) [8, 63]. This provides an explanation for the relationship between trypanosomes infecting arboreal fauna inhabiting distant regions.

The trypanosome sequence we identified in the regent honeyeater likely belongs to T. thomasbancrofti (genotype 1), and T. thomasbancrofti was originally described in the regent honeyeater [41]. This trypanosome species has been suggested to be a culicid-vectored parasite and has been detected in healthy captive and wild regent honeyeaters [41]. In contrast, T. avium was identified in the rook (Corvus frugilegus) and associated with serious disease and death in birds, with suggestions that it is transmitted by blackflies (Simulium spp.) [64, 65] and phlebotomine sand flies [21]. Hence, our data corroborated the presence of T. thomasbancrofti in the regent honeyeater and highlight the importance of parasitological surveillance in the wild for this species classified as critically endangered (CR) (sensu IUCN).

Of particular interest was the case of the trypanosome detected in the eastern dwarf tree frog that was related to those identified in amphibians, reptile, and insect species. Since this amphibian trypanosome fell in a divergent and basal position within the clade it might represent a new trypanosome species and hence merits further characterization (Additional file 1: Figure S1; Additional file 6: Figure S2). Interestingly, considering the clinical diagnosis of the frog sampled (see Methods) as well as its transcript abundance (Table 3), it is possible that this trypanosome species or the synergistic infection by Trypanosoma with Myxobolus might have detrimental effects on amphibian health. This clearly merits further investigation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a trypanosome in the eastern dwarf tree frog (Additional file 1: Figure S1), although amphibians are known to be parasitized by different trypanosomes species [15, 16, 66,67,68] and some have been documented in Australian amphibians [15, 67, 69]. That the clade containing the eastern dwarf tree frog sequence also contains a trypanosome infecting sand flies tentatively suggests that dipterans or other invertebrates could play a role vectoring trypanosome transmission [58].

While our study was focused on samples collected from multiple organs and tissues, meta-transcriptomics has previously been shown to be an efficient approach for characterizing blood parasites, even at low abundance [29, 70]. In addition, the technique has been used to detect trypanosome sequences in the blood meals of Ixodes holocyclus ticks and Aedes camptorhynchus mosquitoes [19, 71]. Hence, when combined with more traditional approaches, meta-transcriptomics offers a promising way to shed new light on the ecology and epidemiological surveillance of parasites in nature, although the approach is costly, requires extensive computational resources and may be unable to detect genes that are not expressed to sufficient levels [70].

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-transcriptomic analysis of trypanosomes in native Australian wildlife, expanding the known genetic diversity of these important parasites. Our findings highlight the diversity of trypanosomes infecting an important spectrum of Australian native fauna. We also demonstrated that RNA sequencing is sufficiently sensitive to detect low levels of Trypanosoma transcripts from diverse hosts and tissues types, and hence represents an effective means to detect trypanosomes that are divergent in genome sequence.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional information files. The newly generated contig sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MT732373-MT732384. All new sequence reads are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject accession PRJNA626677 (BioSample accessions: SAMN15401543 - SAMN1540159). The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the figshare repository, https://figshare.com/s/d9c281ada61d8a8ed884.

Abbreviations

- BLAST:

-

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- BPCV2:

-

bandicoot papillomatosis carcinomatosis virus type 2

- cox1:

-

cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1

- CR:

-

critically endangered

- gGAPDH:

-

glycosomal glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- GP63:

-

major surface glycoprotein

- HSPs:

-

heat-shock proteins

- IUCN:

-

International Union for Conservation of Nature

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- nr:

-

non-redundant database

- nt:

-

nucleotide database

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- rRNA:

-

ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- RT-PCR:

-

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SSU:

-

small subunit

- TAS:

-

Tasmania

- Tryp:

-

trypanosome

- TPM:

-

transcripts per million

References

Pinto CM, Ocaña-Mayorga S, Lascano MS, Grijalva MJ. Infection by trypanosomes in marsupials and rodents associated with human dwellings in Ecuador. J Parasitol. 2006;92:1251–5.

Mackie J, Stenner R, Gillett A, Barbosa A, Ryan U, Irwin P. Trypanosomiasis in an Australian little red flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). Aust Vet J. 2017;95:259–61.

Jakes KA, O’Donoghue PJ, Adlard RD. Phylogenetic relationships of Trypanosoma chelodina and Trypanosoma binneyi from Australian tortoises and platypuses inferred from small subunit rRNA analyses. Parasitol. 2001;123:483–7.

Barbosa AD, Gofton AW, Paparini A, Codello A, Greay T, Gillett A, et al. Increased genetic diversity and prevalence of co-infection with Trypanosoma spp. in koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) and their ticks identified using next-generation sequencing (NGS). PLoS One. 2017;12:1–20.

Hamilton PB, Stevens JR, Gidley J, Holz P, Gibson WC. A new lineage of trypanosomes from Australian vertebrates and terrestrial bloodsucking leeches (Haemadipsidae). Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:431–43.

Cooper C, Keatley S, Northover A, Gofton AW, Brigg F, Lymbery AJ, et al. Next generation sequencing reveals widespread trypanosome diversity and polyparasitism in marsupials from Western Australia. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2018;7:58–67.

Thompson CK, Godfrey SS, Thompson RCA. Trypanosomes of Australian mammals: a review. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2014;3:57–66.

Cooper C, Clode PL, Peacock C, Thompson RCA. Host-parasite relationships and life histories of trypanosomes in Australia. Adv Parasitol. 2017;97:47–109.

Godfrey SS, Keatley S, Botero A, Thompson CK, Wayne AF, Lymbery AJ, et al. Trypanosome co-infections increase in a declining marsupial population. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2018;7:221–7.

Botero A, Thompson CK, Peacock CS, Clode PL, Nicholls PK, Wayne AF, et al. Trypanosomes genetic diversity, polyparasitism and the population decline of the critically endangered Australian marsupial, the brush tailed bettong or woylie (Bettongia penicillata). Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2013;2:77–89.

McInnes LM, GIillett A, Hanger J, Reid SA, Ryan UM. The potential impact of native Australian trypanosome infections on the health of koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Parasitology. 2011;138:873–83.

Paparini A, Irwin PJ, Warren K, McInnes LM, de Tores P, Ryan UM. Identification of novel trypanosome genotypes in native Australian marsupials. Vet Parasitol. 2011;183:21–30.

McInnes LM, Gillett A, Ryan UM, Austen J, Campbell RSF, Hanger J, et al. Trypanosoma irwini n. sp (Sarcomastigophora: Trypanosomatidae) from the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Parasitology. 2009;136:875–85.

Mackerras M, Mackerras I. The haematozoa of Australian frogs and fish. Aust J Zool. 1961;9:123.

O’Donoghue PJ, Adlard RD. Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Mem Queensland Mus. 2000;45:1–163.

Spodareva VV, Grybchuk-Ieremenko A, Losev A, Votýpka J, Lukeš J, Yurchenko V, et al. Diversity and evolution of anuran trypanosomes: insights from the study of European species. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:447.

Kreier JP. Parasitic Protozoa. 2nd ed. San Diego: Elsevier Science; 2013.

Krige A-S, Thompson RCA, Clode PL. Hang on a tick—are ticks really the vectors for Australian trypanosomes? Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:596–606.

Harvey E, Rose K, Eden JS, Lo N, Abeyasuriya T, Shi M, et al. Extensive diversity of RNA viruses in Australian ticks. J Virol. 2019;93:e01358–418.

Ferreira RC, De Souza AA, Freitas RA, Campaner M, Takata CSA, Barrett TV, et al. A phylogenetic lineage of closely related trypanosomes (Trypanosomatidae, Kinetoplastida) of anurans and sand flies (Psychodidae, Diptera) sharing the same ecotopes in Brazilian Amazonia. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2008;55:427–35.

Svobodová M, Rádrová J. Phlebotomine sandflies—potential vectors of avian trypanosome. Acta Protozool. 2018;57:53–9.

Svobodová M, Dolnik OV, Čepička I, Rádrová J. Biting midges (Ceratopogonidae) as vectors of avian trypanosomes. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:224.

Fermino BR, Paiva F, Viola LB, Rodrigues CMF, Garcia HA, Campaner M, et al. Shared species of crocodilian trypanosomes carried by tabanid flies in Africa and South America, including the description of a new species from caimans, Trypanosoma kaiowa n. sp. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:225.

Argañaraz ER, Hubbard GB, Ramos LA, Ford AL, Nitz N, Leland MM, et al. Blood-sucking lice may disseminate Trypanosoma cruzi infection in baboons. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001;43:271–6.

Bartlett-Healy K, Crans W, Gaugler R. Vertebrate hosts and phylogenetic relationships of amphibian trypanosomes from a potential invertebrate vector, Culex territans Walker (Diptera: Culicidae). J Parasitol. 2009;95:381–7.

Nuttall GHF. The transmission of Trypanosoma lewisi by fleas and lice. Parasitology. 1908;1:296–301.

Hutchinson R, Stevens JR. Barcoding in trypanosomes. Parasitology. 2018;145:563–73.

Hamilton PB, Stevens JR, Gaunt MW, Gidley J, Gibson WC. Trypanosomes are monophyletic: evidence from genes for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase and small subunit ribosomal RNA. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1393–404.

Galen SC, Borner J, Williamson JL, Witt CC, Perkins SL. Metatranscriptomics yields new genomic resources and sensitive detection of infections for diverse blood parasites. Mol Ecol Resour. 2020;20:14–28.

Shakya M, Lo C-C, Chain PSG. Advances and challenges in metatranscriptomic analysis. Front Genet. 2019;10:904.

Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63.

Stark R, Grzelak M, Hadfield J. RNA sequencing: the teenage years. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:631–56.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–52.

Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12:59–60.

Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, et al. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:222–6.

Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Meth. 2017;14:587–9.

Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:268–74.

Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol. 1981;17:368–76.

Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–21.

Šlapeta J, Morin-Adeline V, Thompson P, McDonell D, Shiels M, Gilchrist K, et al. Intercontinental distribution of a new trypanosome species from Australian endemic regent honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia). Parasitology. 2016;143:1012–25.

Noyes H, Stevens J, Teixeira M, Phelan J, Holz P. A nested PCR for the ssrRNA gene detects Trypanosoma binneyi in the platypus and Trypanosoma sp. in wombats and kangaroos in Australia. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29:331–9.

Pallavi R, Roy N, Nageshan RK, Talukdar P, Pavithra SR, Reddy R, et al. Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target against protozoan infections: biochemical characterization of HSP90 from plasmodium falciparum and Trypanosoma evansi and evaluation of its inhibitor as a candidate drug. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37964–75.

Palmer G, Louvion JF, Tibbetts RS, Engman DM, Picard D. Trypanosoma cruzi heat-shock protein 90 can functionally complement yeast. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;70:199–202.

Pérez-Morales D, Lanz-Mendoza H, Hurtado G, Martínez-Espinosa R, Espinoza B. Proteomic analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes subjected to heat shock. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;902803.

Hoter A, El-Sabban ME, Naim HY. The HSP90 family: structure, regulation, function, and implications in health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2560.

Dunn BM. Frontiers in protein and peptide sciences. Volume 1. Bentham Books. 2018.

Donelson JE, Hill KL, El-Sayed NMA. Multiple mechanisms of immune evasion by African trypanosomes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;91:51–66.

LaCount DJ, Gruszynski AE, Grandgenett PM, Bangs JD, Donelson JE. Expression and function of the Trypanosoma brucei major surface protease (GP63) genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24658–64.

Guerbouj S, Victoir K, Guizani I, Seridi N, Nuwayri-Salti N, Belkaid M, et al. Gp63 gene polymorphism and population structure of Leishmania donovani complex: Influence of the host selection pressure? Parasitology. 2001;122:25–35.

Thompson CK, Wayne AF, Godfrey SS, Thompson R. Temporal and spatial dynamics of trypanosomes infecting the brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata): a cautionary note of disease-induced population decline. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:169.

Barbosa A, Reiss A, Jackson B, Warren K, Paparini A, Gillespie G, et al. Prevalence, genetic diversity and potential clinical impact of blood-borne and enteric protozoan parasites in native mammals from northern Australia. Vet Parasitol. 2017;238:94–105.

Rose K, Kirkland P, Davis R, Cooper D, Blumstein D, Pritchard L, et al. Epizootics of sudden death in tammar wallabies (Macropus eugenii) associated with an orbivirus infection. Aust Vet J. 2012;90:505–9.

Woolford L, Rector A, Van Ranst M, Ducki A, Bennett MD, Nicholls PK, et al. A novel virus detected in papillomas and carcinomas of the endangered western barred bandicoot (Perameles bougainville) exhibits genomic features of both the Papillomaviridae and Polyomaviridae. J Virol. 2007;81:13280–90.

Keane C, Taylor MRH, Wilson P, Smith L, Cunningham B, Devine P, et al. Bacteroides ruminicola as a possible cause of “lumpy-jaw” in Bennett’s wallabies. Vet Microbiol. 1977;2:179–83.

McLelland D. Macropod progressive periodontal disease (“lumpy-jaw”). In: Vogelnest L, Portas T, editors. Current therapy in medicine of Australian mammals. Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2019. p. 451–62.

Muzari MO. Tabanid flies and potential transmission of Trypanosoma evansi in Queensland. Ph.D. Thesis, James Cook University, Queensland, Australia; 2010. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/19035/.

Kato H, Uezato H, Sato H, Bhutto AM, Soomro FR, Baloch JH, et al. Natural infection of the sand fly Phlebotomus kazeruni by Trypanosoma species in Pakistan. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:10.

Kjos SA, Marcet PL, Yabsley MJ, Kitron U, Snowden KF, Logan KS, et al. Identification of bloodmeal sources and Trypanosoma cruzi infection in triatomine bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) from residential settings in Texas, the United States. J Med Entomol. 2013;50:1126–39.

Buitrago R, Bosseno MF, Depickère S, Waleckx E, Salas R, Aliaga C, et al. Blood meal sources of wild and domestic Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Bolivia: connectivity between cycles of transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:214.

Cortez MR, Pinho AP, Cuervo P, Alfaro F, Solano M, Xavier SCC, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi (Kinetoplastida Trypanosomatidae): ecology of the transmission cycle in the wild environment of the Andean valley of Cochabamba, Bolivia. Exp Parasitol. 2006;114:305–13.

Hamilton PB, Gibson WC, Stevens JR. Patterns of co-evolution between trypanosomes and their hosts deduced from ribosomal RNA and protein-coding gene phylogenies. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;44:15–25.

Dario MA, Lisboa CV, Costa LM, Moratelli R, Nascimento MP, Costa LP, et al. High Trypanosoma spp. diversity is maintained by bats and triatomines in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188412.

Votýpka J, Oborník M, Volf P, Svobodová M, Lukeš J. Trypanosoma avium of raptors (Falconiformes): phylogeny and identification of vectors. Parasitology. 2002;125:253–63.

Tarello W. Trypanosoma avium incidence, pathogenicity and response to melarsomine in falcons from Kuwait. Parasite. 2005;12:85–7.

Werner JK, Walewski K. Amphibian trypanosomes from the McCormick forest, Michigan. J Parasitol. 1976;62:20.

Johnston TH. A census of the endoparasites recorded as occurring in Queensland, arranged under their hosts. Brisbane, Qld: Royal Society of Queensland; 1916.

Bardsley JE, Harmsen R. The trypanosomes of Anura. Adv Parasitol. 1973;11:1–73.

Cleland J, Johnston T. The haematozoa of Australian batrachians. J Proc R Soc New South Wales. 1910;44:252–61.

Cassin-Sackett L. Promising protocols for parasites: Metatranscriptomics improves detection of hyperdiverse but low abundance communities. Mol Ecol Resour. 2020;20:8–10.

Shi M, Neville P, Nicholson J, Eden J-S, Imrie A, Holmes EC. High-resolution metatranscriptomics reveals the ecological dynamics of mosquito-associated RNA viruses in Western Australia. J Virol. 2017;91:1–17.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the financial support and samples from Taronga Conservation Society Australia, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, and Parks Australia.

Funding

ECH is supported by an ARC Australian Laureate Fellowship (FL170100022). The funders had no role in study design, data analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ECH conceived the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Animal sampling was performed by EH, SC, AP and KR. Metagenomic sequencing and analysis of the sequence data generated, including phylogenetic analysis, was performed by ASOB, KC, J-SE, W-SC, EH and JHOP. The interpretation of the trypanosome data was performed by JŠ, while KR interpreted the pathological data. All authors contributed to writing the original draft of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Samples were collected during routine diagnostic procedures under the auspices of the Taronga Animal Ethics Committee’s Opportunistic Sample Collection Programme, and under scientific licence #SL100104 issued by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage and valid 2 May 2011 to 30 April 2021.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

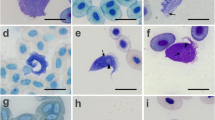

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Light microphotograph of the promastigote phase of Trypanosoma sp. in giemsa-stained blood film from Litoria fallax. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Additional file 2

: Table S1. Summary of contigs with hits against trypanosome sequences at the NCBI nucleotide (nt) database. Relative abundance was calculated for each contig as transcripts per million (TPM).

Additional file 3: Table S2.

List of PCR primers used in this study for confirmation of trypanosome infection.

Additional file 4: Table S3.

List of sequences used for phylogenetic analysis.

Additional file 5: Table S4.

Pairwise sequence identity among 18S rRNA sequences of avian trypanosomes belonging to genotypes 1–4 and the putative T. thomasbancrofti identified in this study. Genotype classification sensu Šlapeta et al. (2016) [41].

Additional file 6: Figure S2.

Maximum likelihood tree showing phylogenetic relationships among trypanosomes within the aquatic clade based on the 18S rRNA gene. The trypanosome identified in Litoria fallax is indicated in blue. The hosts of trypanosomes are indicated with colour-coded tips.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ortiz-Baez, A.S., Cousins, K., Eden, JS. et al. Meta-transcriptomic identification of Trypanosoma spp. in native wildlife species from Australia. Parasites Vectors 13, 447 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04325-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04325-6