Abstract

Background

Across most of sub-Saharan Africa, malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes from the Anopheles gambiae complex, comprising seven morphologically indistinguishable but behaviourally-diverse sibling species with ecologically-distinct environmental niches. Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis are the mostly widely distributed major malaria vectors within the complex, while An. quadriannulatus is sparsely distributed.

Methods

Indoor residual spraying (IRS) with the organophosphate pirimiphos-methyl (PM) was conducted four times between 2011 and 2017 in the Luangwa Valley, south-east Zambia. Anopheles mosquitoes were repeatedly collected indoors by several experiments with various objectives conducted in this study area from 2010 onwards. Indoor mosquito collection methods included human landing catches, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention miniature light traps and back pack aspirators. Anopheles gambiae complex mosquitoes were morphologically identified to species level using taxonomic keys, and to molecular level by polymerase chain reaction. These multi-study data were collated so that time trends in the species composition of this complex could be assessed.

Results

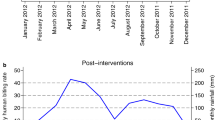

The proportion of indoor An. gambiae complex accounted for by An. quadriannulatus declined from 95.1% to 69.7% following two application PM-IRS rounds with an emulsifiable concentrate formulation from 2011 to 2013, while insecticidal net utilisation remained consistently high throughout that period. This trend continued after two further rounds of PM-IRS with a longer-lasting capsule suspension formulation in 2015 and 2016/2017, following which An. quadriannulatus accounted for only 4.5% of the complex. During the same time interval there was a correspondingly steady rise in the proportional contribution of An. arabiensis to the complex, from 3.9 to 95.1%, while the contribution of nominate An. gambiae remained stable at ≤ 0.9%.

Conclusion

It seems likely that An. arabiensis is not only more behaviourally resilient against IRS than An. gambiae, but also than An. quadriannulatus populations exhibiting indoor-feeding, human-feeding and nocturnal behaviours that are unusual for this species. Routine, programmatic entomological monitoring of dynamic vector population guilds will be critical to guide effective selection and deployment of vector control interventions, including supplementary measures to tackle persisting vectors of residual malaria transmission like An. arabiensis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

World malaria cases have fallen from 271 million in 2000 to 212 million in 2015, a reduction of 22% and within the same time period the number of deaths has equally reduced from an estimated 830,000 in 2000 to 429,000 [1]. Vector control interventions such as long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) are responsible for most of these gains [1,2,3].

Malaria transmission in most parts of Africa is primarily sustained by mosquitoes from the An. gambiae complex and the An. funestus group. The An. gambiae complex is composed of seven cryptic sibling species, with An. gambiae and An. arabiensis being amongst the most efficient and broadly distributed malaria vectors [4,5,6,7,8,9]. The sibling species within this complex are morphologically indistinguishable, but reproductively isolated and behaviourally diverse, with ecologically distinct environmental niches distributed across sub-Saharan Africa [7, 10, 11]. For example, An. gambiae typically bites humans at night when they are sleeping and then rests indoors afterwards, so it is vulnerable to control with indoor interventions such as LLINs and IRS [12, 13]. An. arabiensis can also exhibit these same anthropophagic, endophagic behaviours, but is far more behaviourally plastic and can avoid such indoor interventions by feeding outdoors upon animals or upon people when they are unprotected [14]. Furthermore, An. arabiensis can also feed indoors but then rapidly escape from houses through various openings such as eaves, to rest safely outdoors without fatal exposure to insecticides [15,16,17,18,19]. In contrast, An. quadriannulatus is another sibling species from this complex that has a more limited distribution in arid areas, where it mediates little [20] or no transmission. This species is usually not considered to be a vector of malaria because it typically feeds upon animals [21, 22] which do not carry Plasmodium parasite species capable of infecting humans. However, in the Luangwa Valley, south-east of Zambia, it was found in sympatry with An. gambiae and An. arabiensis, where it predominantly attacked humans indoors at night in far greater numbers than the other two sibling species [22,23,24]. Since those original characterizations of this unusual vector guild in south-east Zambia [20], IRS with the organophosphate pirimiphos-methyl (PM) was introduced and repeated over several years [25]. Therefore, the overall goal of this retrospective observational study was to determine whether PM-IRS had any selective impact on the indoor species composition of the An. gambiae complex overtime.

Methods

Sources of retrospective data

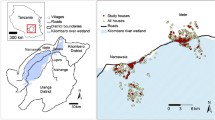

All the studies from which the sibling species composition data are presented here, were conducted and collated from Chisobe village, situated south-east of Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia. This area is characterised by having pyrethroid-resistant An. funestus as the major malaria vector responsible for malaria transmission [23, 25,26,27]. The Zambia National Malaria Elimination Programme initiated mass LLINs distribution campaigns in 2005 and this area was one of the first beneficiaries in 2005/2006 and again in 2008/2009 [23], as well as more recently through campaigns in 2013 and 2017. Additionally, IRS has been conducted in this setting from 2011 to 2013 with an emulsifiable concentrate formulation of pirimiphos-methyl (PM) (Actellic 50EC®, Syngenta AG, Cape Town, South Africa) that has relatively short-lived effectiveness [28, 29]. This was then followed by two IRS spray rounds with a longer lasting capsule suspension formulation of PM (Actellic 300CS®, Syngenta AG, Cape Town, South Africa) [30,31,32] in 2015 and 2016/2017.

The species composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex of sibling species was evaluated as part of various studies with different objectives, conducted intermittently between 2010 and 2017. The first experiments in 2010 involved a 3 × 3 Latin Square design evaluation of three different sets of trapping methods in local houses with two blocks of three houses, with one group having LLINs alone while the other had a combination of LLINs and IRS with deltamethrine (K-Othrine WG250 Bayer Environmental Science, Johannesburg, South Africa). The first set of trapping methods consisted of human landing catches both indoors and outdoors, while the second had a CDC light trap indoors and the third had resting boxes placed indoors and outdoors. Each of the trapping methods were rotated through the three households over three consecutive nights, and this rotation schemes was repeated over 10 rounds of replication [24, 33]. In the subsequent studies in 2014, 2016 and 2017, four experimental huts of the Ifakara design [34, 35] were built in the same village and mosquitoes were collected indoors during evaluations of various IRS formulations, which were deployed as either their intended IRS format [34, 35] or treatments for window screens and eave baffles [36]. Eight adult men were recruited to sleep in the huts overnight from 19:00 to 07:00 h and the two sleepers were assigned to a single specified hut for the duration of the experiments. All the sleepers slept under an intact LLIN (Permanet.2.0, Vestergaard Frandsen, Nairobi, Kenya without any holes. Every morning at 07:00 h, indoor resting mosquitoes were retrieved using back pack aspirators [36].

In order to mitigate against sampling inconsistencies between the different collection methods used, only mosquitoes caught indoors were considered for this analysis of temporal trends in sibling species composition. All mosquitoes of the An. gambiae complex were initially morphologically identified to species level using various taxonomic keys [4] and recorded as unfed, partly fed, fed and gravid. Mosquitoes were then further processed to classify them to sibling species level by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [37]. In order to avoid any introduction of any sampling bias by selective impact of insecticidal active ingredients of the LLINs, IRS or treated window screens and eave baffles, data for all PCR-amplified specimens from the An. gambiae complex were included, regardless of whether they were alive or dead when collected, or which collections method they were obtained with. Additionally, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect sporozoites in the heads and thoraces of the 2016 samples only.

Data analysis

The data was analysed using the open-source statistical software package R (3.2.1) to fit generalised linear models (GLMs) with a logistic link function and binomial error distribution. Fitted GLMs assessed the effect of time (continuous predictor) on the proportion of the An. gambiae complex accounted for by each of the three sibling species.

Results

From the 2010 indoor household experiments, a total of 1112 specimens of the An. gambiae complex were identified to species level by PCR. The proportional composition of these samples was dominated by An. quadriannulatus (95.2%) when compared to An. arabiensis (3.9%) and An. gambiae (0.9%). From the 2014 experiments, 218 specimens of the An. gambiae complex were identified to sibling species level. Anopheles quadriannulatus (69.7%) was still the most proportionally dominant species, but a much greater share was accounted for by An. arabiensis (30.3%). Out of 897 An. gambiae specimens identified to sibling species level in 2016, An. arabiensis (85.7%) was proportionally the most abundant, while An. quadriannulatus only accounted for a minor fraction of the complex (14.2%) and nominate An. gambiae remained very sparse (0.2%). In 2017, out of 285 specimens identified to species level, almost all were An. arabiensis (95.1%), with An. quadriannulatus (4.5%) and An. gambiae (0.4%) contributing only very minor fractions. The overall steady downward trend in the proportional contribution of An. quadriannulatus over the course of the study (Z = -21.1 P < 0.0001), and the corresponding upward trend for An. arabiensis (Z = -28.9, P < 0.0001), is presented graphically in the context of IRS rounds in Fig. 1. Only one sporozoite-positive An. arabiensis was identified out of 769 tested specimens from An. gambiae complex samples collected in 2016.

Discussion

The steady proportional decline of indoor biting An. quadriannulatus and corresponding rise of An. arabiensis may be attributed to PM-IRS, first with a short-lived formulation in 2011 and 2013, and then followed by a more effective, longer-lasting formulation which immediately achieved even greater impact on vector densities and human malaria infection burden [25]. These observations add further evidence to support supplementing pyrethroid-treated LLINs with IRS using an alternative insecticide with a different mode of action from another chemical class [38]. This can therefore effectively control indoor-feeding secondary vectors like this local An. quadriannulatus population which has been incriminated previously as a vector of residual transmission in this setting [20].

On the other hand, the proportion of the An. gambiae complex accounted for An. arabiensis correspondingly increased over the same time period. It is highly unlikely that between-species differences of insecticide susceptibility could explain these observed shifts in species complex composition, because no resistance to PM has been documented to date within the An. gambiae complex anywhere in Zambia (NMEC, personal comms). The increased relative abundance of An. arabiensis may therefore have arisen from the known behavioural resilience of this species, which evades contact with insecticides by feeding on animals (zoophagic), feeding outdoors (exophagic), resting outdoors (exophilic) and expressing early-exiting behaviours that make it less vulnerable to IRS or LLINs [14, 18].

In this particular case, zoophagy seems an unlikely contributor to the preferential survival and increasing dominance of An. arabiensis over time, because the previously dominant species was the even more zoophagic An. quadriannulatus, rather than anthropophagic An. gambiae. Furthermore, while behavioural characterizations in this study site in 2011 and 2012 confirm that the local An. quadriannulatus population is indeed strongly zoophagic, these same experiments reveal an unusually strong preference for humans amongst An. arabiensis, which completely ignored cattle and goats when offered a choice between these three different sources of blood [20].

However, some populations of An. arabiensis can feed early in the evening when many people are active outdoors, where they are not protected by either LLINs or IRS. Secondly, An. arabiensis consistently suffer much lower mortality than either An. gambiae or An. funestus inside huts containing LLINs or IRS, even with insecticides to which they are completely susceptible [13, 39, 40], apparently because they forage far more briefly and cautiously within houses and then exit before they are fatally exposed [41,42,43].

While IRS clearly must have reduced An. quadriannulatus population densities indoors, and could have reduced inter-specific competition within the taxon sufficiently to enable genuine species replacement in the strict sense [44, 45]. However, the data presented here only represent proportions from within samples of varying size collected with varying methods on an intermittent basis, so it is not possible to unambiguously conclude that the densities of An. arabiensis increased in absolute rather than relative terms.

The shifting proportional balance of these two species could be readily explained by a simple reduction in the number of An. quadriannulatus biting indoors, even without any corresponding increase in An. arabiensis densities. However, it is not possible to distinguish between simple selective suppression of some species more than others [18, 46] versus true population replacement [44] without consistent, year-round longitudinal density measurements using fixed trapping over the full course of the period in question. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge this is the first report demonstrating the proportional decline of indoor-biting An. quadriannulatus of probably modest vectorial capacity, specifically associated with a corresponding steady rise of An. arabiensis, which is known to be widely important vector of residual malaria transmission across many parts of Africa [19, 42, 43]. These observations are therefore potentially important from an epidemiological and vector control perspective, especially if An. arabiensis has replaced An. quadriannulatus in the strict sense, and does prove to be a more efficient malaria vector.

As many vector control programmes re-orient themselves from malaria control to elimination, improved and novel control tools that specifically target behaviourally-evasive vectors like An. arabiensis should be considered as potential supplements to IRS and LLINs [47]. Emerging new approaches, such as insecticide vapour emanators, attractive toxic sugar baits and mosquito-proofed housing [48] should be prioritised for evaluation as possible ways to tackle residual malaria transmission of behaviourally-resilient vectors like An. arabiensis.

Of course, a retrospective observational study such as this has many limitations, notably the inconsistent and intermittent way in which mosquitoes were captured. Also, the houses and experimental huts in which they were captured varied in terms of whether their occupants used pyrethroid-treated LLINs, and whether they had been sprayed with PM. Unfortunately, it was not possible to link the molecular species identity results back to structure identity and records for the presence of LLINs or IRS treatments, so the repellent, irritant and insecticidal properties of these insecticidal measures may have affected species composition by differentially influencing the behaviour and survival of distinct sibling species. Other limitations include non-availability of data on of blood meal sources, while sporozoite rates were only assessed for the 2016 samples, with only one infected An. arabiensis specimen identified, so this collation of retrospective data cannot be used to infer any temporal change in sporozoite prevalence or malaria transmission. These kinds of inconsistencies are typical of such opportunistic secondary analyses of data collected with project-based research funding, because the diversity of experiments from which data were collated were originally designed to address a range of very different, loosely-related questions [18]. Also, these observations come from only one village in the Luangwa valley and cannot be considered representative of national or even provincial-level trends. Programmatically-funded and managed surveillance platforms are clearly required in Zambia and most other tropical countries for sustained, consistent longitudinal monitoring of mosquito population dynamics [49], as well as the behavioural and insecticide resistance traits that drive these trends [18, 47]. Furthermore, it will be important to quantify how much An. arabiensis and other persisting vectors contribute to residual malaria transmission, and to unambiguously determine whether genuine population replacement [44] of previously abundant vectors like An. quadriannulatus has actually occurred.

Conclusions

Despite these study limitations, this study yields insights that further reinforces the case for establishing continuous and rigorous entomological surveillance, so as to monitor vector species abundance and composition indefinitely over time. Additionally, surveillance will be critical in order identify which vectors are contributing to residual transmission in areas with high coverage of LLINs and IRS. This will enable malaria vector control programmes to rationally deploy improved and/or novel vector control tools to specifically target vectors like An. arabiensis which respond poorly to control with LLINs or IRS.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centre for disease control

- HLC:

-

Human landing catches

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- LLINs:

-

Long lasting insecticidal nets

- PM:

-

Pirimiphos-methyl

References

WHO. World Malaria Report. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015;526:207–11.

Gething PW, Casey DC, Weiss DJ, Bisanzio D, Bhatt S, Cameron E, et al. Mapping Plasmodium falciparum mortality in Africa between 1990 and 2015. New Engl J Med. 2016;375:2435–45.

Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara (Afrotropical region). Johannesburg: South African Medical Research Institute; 1987.

Temu EA, Minjas JN, Coetzee M, Hunt RH, Shift CJ. The role of four anopheline species (Diptera: Culicidae) in malaria transmission in coastal Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:152–8.

Coetzee M, Fontenille D. Advances in the study of Anopheles funestus, a major vector of malaria in Africa. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:599–605.

Coetzee M. Distribution of the African malaria vectors of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:103–4.

Gillies MT, De Meillon B. A suppliment to the anophilinae South of the Sahara. Johannesburg: South African Medical Research Institute; 1968.

Kaindoa EW, Matowo NS, Ngowo HS, Mkandawile G, Mmbando A, Finda M, et al. Interventions that effectively target Anopheles funestus mosquitoes could significantly improve control of persistent malaria transmission in south-eastern Tanzania. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177807.

Coetzee M, Craig M, le Sueur D. Distribution of African malaria mosquitoes belonging to the Anopheles gambiae complex. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:74–7.

Coluzzi M. Malaria vector analysis and control. Parasitol Today. 1992;8:113–8.

Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Orindi BO, Muturi EJ, Midega JT, Nzovu J, et al. Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013;12:13.

Kitau J, Oxborough RM, Tungu PK, Matowo J, Malima RC, Magesa SM, et al. Species shifts in the Anopheles gambiae complex: do LLINs successfully control Anopheles arabiensis? PLoS One. 2012;7:e31481.

Govella NJ, Chaki PP, Killeen GF. Entomological surveillance of behavioural resilience and resistance in residual malaria vector populations. Malar J. 2013;12:124.

Githeko AK, Adungo NI, Karanja DM, Hawley WA, Vulule JM, Seroney IK, et al. Some observations on the biting behavior of Anopheles gambiae s.s., Anopheles arabiensis, and Anopheles funestus and their implications for malaria control. Exp Parasitol. 1996;82:306–15.

Shililu J, Ghebremeskel T, Seulu F, Mengistu S, Fekadu H, Zerom M, et al. Seasonal abundance, vector behavior, and malaria parasite transmission in Eritrea. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2004;20:155–64.

Tirados I, Costantini C, Gibson G, Torr SJ. Blood-feeding behaviour of the malarial mosquito Anopheles arabiensis: implications for vector control. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:425–37.

Killeen GF. Characterizing, controlling and eliminating residual malaria transmission. Malar J. 2014;13:330.

Killeen GF, Kiware SS, Okumu FO, Sinka ME, Moyes CL, Massey NC, et al. Going beyond personal protection against mosquito bites to eliminate malaria transmission: population suppression of malaria vectors that exploit both human and animal blood. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2:e000198.

Lobo NF, St Laurent B, Sikaala CH, Hamainza B, Chanda J, Chinula D, et al. Unexpected diversity of Anopheles species in eastern Zambia: implications for evaluating vector behavior and interventions using molecular tools. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17952.

Prior A, Torr SJ. Host selection by Anopheles arabiensis and An. quadriannulatus feeding on cattle in Zimbabwe. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:207–13.

Pates HV, Takken W, Curtis CF, Huisman PW, Akinpelu O, Gill GS. Unexpected anthropophagic behaviour in Anopheles quadriannulatus. Med Vet Entomol. 2001;15:293–8.

Seyoum A, Sikaala CH, Chanda J, Chinula D, Ntamatungiro AJ, Hawela M, et al. Human exposure to anopheline mosquitoes occurs primarily indoors, even for users of insecticide-treated nets in Luangwa Valley, south-east Zambia. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:101.

Sikaala CH, Killeen GF, Chanda J, Chinula D, Miller JM, Russell TL, et al. Evaluation of alternative mosquito sampling methods for malaria vectors in lowland south-east Zambia. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:91.

Hamainza B, Sikaala CH, Moonga HB, Chanda J, Chinula D, Mwenda M, et al. Incremental impact upon malaria transmission of supplementing pyrethroid-impregnated long-lasting insecticidal nets with indoor residual spraying using pyrethroids or the organophosphate, pirimiphos methyl. Malar J. 2016;15:100.

PMI: Africa Indoor Residual Spraying definition of “structure” for IRS in Zambia. Accessed 10 Feb 2017.

Sikaala CH, Chinula D, Chanda J, Hamainza B, Mwenda M, Mukali I, et al. A cost-effective, community-based, mosquito-trapping scheme that captures spatial and temporal heterogeneities of malaria transmission in rural Zambia. Malar J. 2014;13:225.

Aïkpon R, Sèzonlin M, Tokponon F, Okè M, Oussou O, Oké-Agbo F, et al. Good performances but short lasting efficacy of Actellic 50 EC indoor residual spraying (IRS) on malaria transmission in Benin, West Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:256.

Fuseini G, Ebsworth P, Jones S, Knight D. The efficacy of ACTELLIC 50 EC, pirimiphos methyl, for indoor residual spraying in Ahafo, Ghana: area of high vector resistance to pyrethroids and organochlorines. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:437–40.

Dengela D, Seyoum A, Lucas B, Johns B, George K, Belemvire A, et al. Multi-country assessment of residual bio-efficacy of insecticides used for indoor residual spraying in malaria control on different surface types: results from program monitoring in 17 PMI/USAID-supported IRS countries. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:71.

Oxborough RM, Kitau J, Jones R, Feston E, Matowo J, Mosha FW, et al. Long-lasting control of Anopheles arabiensis by a single spray application of micro-encapsulated pirimiphos-methyl (Actellic(R) 300 CS). Malar J. 2014;13:37.

Chanda E, Chanda J, Kandyata A, Phiri FN, Muzia L, Haque U, et al. Efficacy of ACTELLIC 300 CS, pirimiphos methyl, for indoor residual spraying in areas of high vector resistance to pyrethroids and carbamates in Zambia. J Med Entomol. 2013;50:1275–81.

Seyoum A, Sikaala CH, Chanda J, Chinula D, Ntamatungiro AJ, Hawela M. Most exposure to Anopheles funestus and Anopheles quadriannulatus in Luangwa Valley, south-east Zambia occurs indoors, even for users of insecticidal nets. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:101.

Massue DJ, Kisinza WN, Malongo BB, Mgaya CS, Bradley J, Moore JD, et al. Comparative performance of three experimental hut designs for measuring malaria vector responses to insecticides in Tanzania. Malar J. 2016;15:165.

Okumu FO, Moore J, Mbeyela E, Sherlock M, Sangusangu R, Ligamba G, et al. A modified experimental hut design for studying responses of disease-transmitting mosquitoes to indoor interventions: the Ifakara experimental huts. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30967.

Chinula D, Sikaala CH, Chanda-Kapata P, Hamainza B, Zulu R, Reimer L, et al. Wash-resistance of pirimiphos-methyl insecticide treatments of window screens and eave baffles for killing indoor-feeding malaria vector mosquitoes: an experimental hut trial, south-east of Zambia. Malar J. 2018;17:164.

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–9.

WHO. Global Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012.

Okumu FO, Kiware SS, Moore SJ, Killeen GF. Mathematical evaluation of community level impact of combining bed nets and indoor residual spraying upon malaria transmission in areas where the main vectors are Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:17.

Okumu FO, Mbeyela E, Ligamba G, Moore J, Ntamatungiro AJ, Kavishe DR, et al. Comparative evaluation of combinations of long-lasting insecticidal nets and indoor residual spraying, relative to either method alone, for malaria vector control in an area dominated by Anopheles arabiensis. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:46.

Killeen GF, Chitnis N. Potential causes and consequences of behavioural resilience and resistance in malaria vector populations: a mathematical modelling analysis. Malar J. 2014;13:97.

Killeen GF, Govella NJ, Lwetoijera DW, Okumu FO. Most outdoor malaria transmission by behaviourally-resistant Anopheles arabiensis is mediated by mosquitoes that have previously been inside houses. Malar J. 2016;15:225.

Shcherbacheva A, Haario H, Killeen GF. Modeling host-seeking behavior of African malaria vector mosquitoes in the presence of long-lasting insecticidal nets. Math Biosci. 2018;295:36–47.

Lounibos LP. Competitive displacement and reduction. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2007;23:276–82.

Ferguson HM, Dornhaus A, Beeche A, Borgemeister C, Gottlieb M, Mulla MS, et al. Ecology: a prerequisite for malaria elimination and eradication. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000303.

Killeen GF, Seyoum A, Sikaala C, Zomboko AS, Gimnig JE, Govella NJ, et al. Eliminating malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:172.

Killeen GF, Marshall JM, Kiware SS, South AB, Tusting LS, Chaki PP, et al. Measuring, manipulating and exploiting behaviours of adult mosquitoes to optimise malaria vector control impact. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2:e000212.

Killeen GF, Tatarsky A, Diabate A, Chaccour CJ, Marshall JM, Okumu FO, et al. Developing an expanded vector control toolbox for malaria elimination. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2:e000211.

Killeen GF, Chaki PP, Reed TE, Moyes CL, Govella NJ. Entomological surveillance as a cornerstone of malaria elimination: A critical appraisal. In: Dev V, Manguin S, editors. Towards Malaria Elimination - A Leap Forward. London: IntechOpen; 2018.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study volunteers in Chisobe village for having participated in all the experiments and the Luangwa District Health Management team for their support.

Funding

The 2016 and 2017 experimental hut studies were funded by a Wellcome Trust Masters Training Fellowship awarded to DC (Award number 103271/Z/13/Z). The 2010 and 2014 experiments were funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Malaria Transmission Consortium (Award number 45114).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the present study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DC, CHS, GFK conceived the idea and wrote the first draft manuscript, BH and EC contributed to the manuscript, DRK carried out all molecular analyses and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants in these studies were recruited through a documented informed consent process. For the 2010 indoor collection studies, ethical approval was granted by the National Ethics Committee of the University of Zambia (IRB00001131 of I0RG0000774) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Approval 09.60). All subsequent studies were approved by ERES Converge IRB Zambia (Reference 2015.003) and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Reference 15.044).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chinula, D., Hamainza, B., Chizema, E. et al. Proportional decline of Anopheles quadriannulatus and increased contribution of An. arabiensis to the An. gambiae complex following introduction of indoor residual spraying with pirimiphos-methyl: an observational, retrospective secondary analysis of pre-existing data from south-east Zambia. Parasites Vectors 11, 544 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3121-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3121-0