Abstract

Background

The most potent malaria vectors rely heavily upon human blood so they are vulnerable to attack with insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) within houses. Mosquito taxa that can avoid feeding or resting indoors, or by obtaining blood from animals, mediate a growing proportion of the dwindling transmission that persists as ITNs and IRS are scaled up.

Presentation of the hypothesis

Increasing frequency of behavioural evasion traits within persisting residual vector systems usually reflect the successful suppression of the most potent and vulnerable vector taxa by IRS or ITNs, rather than their failure. Many of the commonly observed changes in mosquito behavioural patterns following intervention scale-up may well be explained by modified taxonomic composition and expression of phenotypically plastic behavioural preferences, rather than altered innate preferences of individuals or populations.

Testing the hypothesis

Detailed review of the contemporary evidence base does not yet provide any clear-cut example of true behavioural resistance and is, therefore, consistent with the hypothesis presented.

Implications of the hypothesis

Caution should be exercised before over-interpreting most existing reports of increased frequency of behavioural traits which enable mosquitoes to evade fatal contact with insecticides: this may simply be the result of suppressing the most behaviourally vulnerable of the vector taxa that constituted the original transmission system. Mosquito taxa which have always exhibited such evasive traits may be more accurately described as behaviourally resilient, rather than resistant. Ongoing national or regional entomological monitoring surveys of physiological susceptibility to insecticides should be supplemented with biologically and epidemiologically meaningfully estimates of malaria vector population dynamics and the behavioural phenotypes that determine intervention impact, in order to design, select, evaluate and optimize the implementation of vector control measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Existing front line tools for malaria vector control, namely insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS), have greatly reduced the malaria burden [1, 2] because the most important mosquito vectors feed predominantly upon people at times when they are inside their houses so that insecticidal contact is maximized [3–5]. These synanthropic vectors can be described as being behaviourally vulnerable to control with such indoor applications of insecticides because it is possible to achieve high coverage of the blood and resting site resources they need to survive. Both recent and historical reports from sub-Saharan Africa show that widespread use of ITNs or IRS change the species composition [6–13] of residual vector populations by progressively diminishing densities of each species in proportion to its physiological susceptibility to insecticides [14], their behavioural vulnerability to insecticide contact [15–17] arising from their propensity to feed (endophagic) or rest (endophilic) indoors [9, 18–20], and their preference for human blood (anthropophagic) [7]. For example, the widespread and exceptionally efficient African vector Anopheles funestus, which feeds almost exclusively upon human blood and predominantly feeds and rests indoors [6, 21], was eliminated from the Pare-Taveta study area in Tanzania during the 1960s following three years of IRS with dieldrin [10]. This species took six years to re-establish itself in the area, during which time it was replaced by Anopheles rivulorum and Anopheles parensis, two morphologically similar species from the same group that prefer to feed outdoors (exophagic) and are generally thought to be of secondary relevance to transmission because they prefer to obtain blood from animals (zoophagic) [6, 10]. In South Africa, An. funestus was eliminated from the entire country by IRS with DDT in the 1950s [22] and was successfully excluded for half a century when a switch to pyrethroids allowed re-invasion by physiologically resistant populations [23]. In the Solomon Islands, IRS and ITN have eliminated Anopheles koliensis, while Anopheles punctulatus is now increasingly uncommon with a patchy distribution, leaving only Anopheles farauti as the sole primary vector, another exophagic species which prefers to bite when most people are outdoors and unprotected [20, 24]. Anopheles darlingi, a domestic and entirely human-feeding vector, was also rapidly eliminated in Guyana by three years of IRS with DDT, leaving Anopheles triannulatus, Anopheles aquasalis and Anopheles albitarsis[25]. In nearby Suriname, both An. darlingi and Anopheles nuneztovari appear to have been eliminated by recent scale-up of ITNs [26].

Many mosquito taxa are remarkably robust to intervention scale-up because they exhibit impressive levels of phenotypic plasticity of the synanthropic behaviours that also make them efficient malaria vectors. The best examples of vulnerability to ITNs and IRS relate to vectors that inflexibly express behavioural phenotypes which expose them to insecticide contact, presumably because these traits are deeply “hard-wired” into their genomes through long association with human hosts [27, 28]. Historical studies of An. funestus in East Africa describe spectacular rigid and absolute preference for humans over animals, even ignoring cattle when they outnumber humans by ten-fold [29]. It is hardly surprising that they were so readily decimated by IRS in this region during the GMEP era [10]. However, most vectors exhibit far greater plasticity of host preference, can obtain blood from animals where they are available [30, 31], and are far less vulnerable to control with IRS and ITNs that only protect human blood sources [32]. Covering humans with nets, or any other personal protection measure, reduces the rate of feeding upon people so the proportion of blood meals obtained from humans inevitably drops if any acceptable alternative hosts are present. The resulting drop in the human blood index of blood-fed mosquito samples is greatest among vectors with the greatest preference for animals in settings where those preferred hosts abound, and is exacerbated by physical barriers and repellent pesticides that deter, rather than kill, mosquitoes [33, 34]. This phenomenon has been demonstrated dozens of times in the field [33, 35], and can occur instantaneously without necessarily requiring any genetic adaptation by the vector.

Across Africa, the timing of biting activity to coincide with human sleeping patterns appears to be a far more important determinant of vector population vulnerability to ITNs than actual preference for feeding indoors or outdoors per se[3, 5]. Correspondingly, substantial changes in observed biting times of An. funestus have been observed following recent scale-up of ITNs in west Africa [36]. The inability of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto to cope with low humidity [37], most probably limits the plasticity with which it can adjust its nocturnal biting activity patterns to avoid ITNs. By comparison, desiccation-tolerant Anopheles arabiensis[37] commonly evades contact with IRS and ITNs by feeding in the early evenings when humans are outdoors [9, 38, 39] and the air remains relatively warm and dry. Within these two species, genetic variability in climatic adaptability may also drive differential vulnerability to IRS [40, 41]. Such heritable phenotypic plasticity allows individual mosquitoes to flexibly adapt their behaviour according to the fine-scale environmental conditions they encounter on a day-to-day basis. As a result, the observed behavioural outcomes may well change in response to intervention scale-up without necessarily reflecting any change in the innate preferences of the vector population through genetic selection [42, 43]. For example, large proportions of mosquitoes that approach houses, with the intention of entering and feeding upon the occupants, are either killed or deterred by IRS and ITNs. Those that survive obviously persist in their search for blood over more extended periods [44] so that a greater proportion of the remaining vector population may exhibit host-seeking behaviours outside of their normal, preferred peak hours of activity.

Presentation of the hypothesis

Many of the recently observed reductions in the frequencies of physiological susceptibility [14, 45, 46] and behavioural vulnerability phenotypes [9, 20, 47] within residual transmission systems, can therefore be readily explained without assuming any selection for physiological or behavioural resistance traits within the distinct taxa that comprise them. This hypothesis is illustrated numerically through simulations of an African malaria transmission system facing increasing ITN coverage, using an established mathematical model with fixed parameters for the behavioural vulnerability and physiological susceptibility traits of the contributing vector species.

All simulations were executed as previously described [34] with equal baseline emergence rates (E0 = 2 × 107 mosquitoes per year) and individual attack availability rates of unprotected humans (ah,u = 1.2 × 10-3 attacks per person per host-seeking mosquito per night) for the two vector species and equal numbers of cattle and humans (Nc = Nh = 1000). All ITN-induced mortality was assumed to occur before feeding so the excess proportion of mosquitoes which are killed after feeding upon a protected human was assumed to be negligible (θμ,post = 0). The simulated An. gambiae and An. arabiensis populations differed only in their parameter values for the proportion of human exposure to bites that occurs indoors (πi = 0.9 versus 0.4, respectively [9, 38]), the attack availability rates of cattle (ac = 2.5 × 10-5 versus 1.9 × 10-3 attacks per person per host-seeking mosquito per night [34] and the excess proportions of mosquitoes which are diverted (θΔ = 0.2 versus 0.6, respectively) or killed before feeding (θμ,pre = 0.8 versus 0.6 while attempting to attack a human while using an ITN [18, 48].

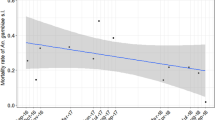

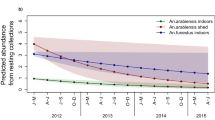

Figure 1 illustrates a simulated baseline scenario with an equal mixture of An. gambiae and An. arabiensis as an example of a typical historical scenario in the east African settings we are familiar with. An. gambiae dominates human exposure to both mosquito bites and malaria transmission before the introduction of ITNs, simply because it feeds almost exclusively upon humans whereas the latter is at least equally likely to feed upon cattle [29, 49]. The lower behavioural vulnerability of An. arabiensis means it is less likely to make fatal contact with nets and causes its proportional contribution to human biting exposure to grow, from a minority of the human-biting vector population in the absence of ITNs, to the majority following successful scale up (Figures 1 and 2A). This is consistent with recent field observations [11, 50] showing that the proportional contribution of An. arabiensis to transmission dramatically increases as ITNs are extensively used.

The impact of high ITN use on the behavioural characteristics and population composition of a transmission systems comprised of a mixed population of An. gambiae and An. arabiensis . The relevant summary outcomes presented reflect the means weighted by relative population size or the relative contributions of these two vector species: A; Sibling species composition, B; Proportion of blood meals taken from humans, and, C; Proportion of human exposure to mosquito bites and malaria transmission occurring indoors.

As a result of the increased relative (but reduced absolute) abundance of An. arabiensis (Figure 2A), the overall proportion of vector blood meals which is obtained from humans are reduced [51] to approximate the lower values often observed for this species (Figure 2B) [29]. The altered species composition of the residual vector population also influences where and when human exposure to mosquito bites occurs (Figure 2C). Consistent with recent field observations, the impact of ITNs upon the proportion of all bites which occurs indoors is relatively modest [9, 38], but it should be noted that the predicted impact upon the proportion of infectious bites occurring indoors is more dramatic, approximating to that of An. arabiensis.

These simulations illustrate how reduced frequencies of vulnerable traits among vector mosquitoes in residual transmission systems may, counter-intuitively, reflect intervention success rather than failure (Figures 1 and 2). By definition, the mosquitoes that are most effectively controlled with a given intervention will always be least represented in surveys of the residual populations that persist following scale up.

Consistent with several other contemporary theoretical studies [52, 53], all the predicted changes in host-seeking outcomes (Figures 1 and 2) are attributable to the phenotypic plasticity of An. arabiensis in particular, and none of these models assume any genetic adaptation of the vector population through heritable alterations of host preference.

Testing the hypothesis

In order to test this hypothesis, the existing evidence base was reviewed to identify any unambiguous examples of altered frequency of innate behavioural preferences of taxonomically homogenous wild malaria vector populations following IRS or ITN scale-up.

Several reports of apparent change in mosquito behaviour can readily be explained by changes in species composition of the vector population, rather than any heritable modifications of the handful the taxa that contribute to persisting transmission. For example [9], the change in distribution of human exposure to a mixture of members of An. gambiae complex reported from Tanzania can probably be attributed to the apparent selective suppression of An. gambiae by ITNs, leaving a transmission system dominated by An. arabiensis. Similarly, the An. gambiae population in Bioko Island [47], was originally composed of two distinct M and S molecular forms that appear to have been differentially affected by IRS [54] and then ITNs so that only the M form remains [47]. Looking further back to the dawn of cytogenetics at the end of the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (GMEP), it was clearly established that the impact of IRS with propoxur upon vector densities varied at village-level geographic scales and was very much dependent upon pre-spray baseline proportions of samples from the An. gambiae complex which were caught resting or feeding indoors, as well as their mean biting time [55]. These behaviours were subsequently proven to differ between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis, making the latter less vulnerable to control with IRS [41]. Recent observations from East Africa indicate that An. arabiensis can also adeptly enter and leave houses without exposing themselves to IRS or ITN formulations of pesticides to which they are fully physiologically susceptible [18, 48]. This form of behavioural plasticity, avoiding contact with ITNs or IRS wherever they are encountered indoors, pre-dates community-wide scale up of these interventions [18] and so cannot be accurately classified as behavioural resistance in the strict sense [14, 56]. It is particularly notable that similar pre-existing traits, specifically short resting times within houses, were identified as the primary obstacle to elimination of malaria transmission by An. nuneztovari, An. darlingi and Anopheles punctimacula in the Americas during the GMEP [16]. The only report of changes in the distribution of biting across the night for a single taxon proven to lack detectable genetic differentiation [42] relates to An. farauti in the Solomon Islands [43]. However, it remains to be proven whether this truly reflects alterations in heritable vector behaviours or simply their altered phenotypic expression in an environment with widespread coverage of vector control measures.

A worrying recent study in Benin reported apparently negligible impact upon malaria transmission by universal coverage schemes for pyrethroid-based ITNs, as well as their supplementation with carbamate-based IRS and insecticide-treated wall linings (ITWL) relative to a reference group of villages receiving only targeted coverage with ITNs [57]. Although these vector populations exhibit high levels of physiological resistance to pyrethroids, they are completely susceptible to carbamates and exhibited slightly increased preference for feeding outdoors where ITNs were supplemented with either IRS or ITWL [57]. As detailed quantitative surveys of feeding and resting behaviours by locally important vectors have not yet been reported, the underlying reasons for lack of incremental impact remain unclear [58]. While it is plausible that gaps in biological coverage [32] arose from behavioural avoidance traits such as those discussed in details above [15, 17, 32], more impressive impacts of supplementary IRS with bendiocarb are apparent elsewhere in Benin [59] and alternative explanations include poor persistence and surface coverage [58]. In the case of the contrast between targeted and universal coverage with ITNs, it must be noted that the improvements in usage achieved by the latter were quite modest [57] and may well offer the most parsimonious explanation for lack of incremental impact upon malaria transmission.

A more worrying recent report from Senegal does raise strong, substantive concerns about the weak impact of vector control, and even rebounding mosquito populations, associated with behavioural and physiological resistance [45]. While it is plausible that epidemiologically relevant behavioural resistance traits have genuinely been selected for in this setting following ITN scale up, significant ambiguity remains because the most relevant vector behaviours have only been partially characterized and all the above interpretational caveats arising from taxonomically selective population suppression and behavioural plasticity may well apply. The extent to which growing frequencies of behavioural and physiological resistance contribute to the observed rebound of transmission remains, therefore, to be determined in this setting.

To conclude, it is clear that intervention-mediated selection for behavioural resistance in the strict sense, meaning an increase in the frequency of heritable behaviour traits in taxonomically homogenous populations which enable them to evade fatal contact with insecticides [14, 56], is of great concern but has yet to be conclusively demonstrated in wild vector populations. The contemporary evidence base does not yet provide any clear-cut example of true behavioural resistance and is therefore consistent with the hypothesis presented.

Implications of the hypothesis

No entomological survey can measure the physiological or behavioural characteristics of dead mosquitoes that have been removed by successful intervention programmes Caution should therefore be exercised before over-interpreting most existing reports of increased frequency of behavioural and physiological resistance traits: this may simply be the result of suppressing the most physiologically susceptible and behaviourally vulnerable of the vector taxa that constituted the original transmission system. Furthermore, none of these field studies can unambiguously attribute these observations to altered frequencies of heritable behavioural preference traits, rather than altered expression of phenotypically plastic behavioural traits in an environment that has been changed by intervention coverage. The importance of plasticity in anthropophagic, endophagic and endophilic behavioural preferences in stabilizing malaria transmission against intervention efforts has long been appreciated [15, 17, 33, 60] and the succinct conclusions of Elliot towards the end of the GMEP appear to be as relevant today as they were four decades ago:

Delays in malaria eradication programmes are caused more by non-response of fully susceptible vectors to attack measures than by physiological resistance, though the latter receives more attention[16].

Greater terminological caution is therefore warranted in relation to use of the terms modification, adapt, shift and resistance in relation to reports of apparent changes in mosquito behaviours. The term resilience, as applied to humans [61–63] and ecosystems [64] may, therefore, be more appropriate for describing pre-existing behaviours that result in evasion of insecticide contact, rather than resistance which infers increasingly ability to do so [14, 56].

Although the contributions of behavioural and physiological resistance to apparent vector population rebound in Senegal remain unclear, there is no reason to doubt the evidence [45] that this has genuinely occurred. There is clearly no room for complacency but there are also good reasons to be optimistic that well-monitored vector populations can be managed, even to the point of local extinction [10, 22, 24, 25] so long as appropriate tools are available that are well matched to their physiological and behavioural characteristics [14, 15, 32, 65]. For example, the rebound of both An. funestus and malaria transmission in South Africa was clearly associated with emergence of physiological resistance to pyrethroids [23], but was effectively tackled by re-introducing DDT [66]. Both examples of vector population and malaria transmission rebound clearly illustrate that such events can only be conclusively documented by longitudinal monitoring of vector population size, the inoculation rates they mediate, and the resulting infection burden among humans. Consistently, continuously and intensively monitored entomological surveillance sites are therefore critical to monitoring, evaluation and planning effective malaria control now and in the future. A particularly important additional reason to monitor and account for behavioural phenotypic plasticity is that it allows organisms to not only cope with population stress in the short-term, but also to evolve more robust adaptive traits in the longer term [67–69]. In the specific case of malaria vectors, recent modelling studies [70] have illustrated how gaps in ITN coverage, including those generated by outdoor feeding behavioural resilience traits [32], can accelerate the equilibration or fixation of physiological resistance alleles. Regardless of whether evasive behaviours observed represent pre-existing resilience or emerging resistance, these will need to be quantified and then targeted with appropriately designed novel interventions that take vector control outside of houses [15, 32, 65].

Ongoing national or regional entomological monitoring surveys of physiological susceptibility [14, 71] should, therefore, be supplemented with biologically and epidemiologically meaningfully [32] estimates of behavioural resilience and resistance phenotypes [9, 18, 20, 29, 36, 47, 49, 72], to design, select and optimize the implementation of vector control measures [3–5, 15, 24, 32]. Beyond standardized physiological susceptibility assays of mosquitoes trapped within small artificial containers [14, 71], experimental hut surveys [18, 73, 74] are required to more realistically estimate entry, exit, resting, host attack, and mortality parameters within houses under near-natural conditions [18, 73, 74]. Furthermore, measurements of human biting rates both indoors and outdoors throughout the night need to be combined with surveys of human behaviour to estimate the proportion of human-vector contact which occurs indoors [4, 38]. While alternative methods for quantifying mosquito-human interactions indoors and outdoors are not yet ready to replace human landing catches [75], recent evidence suggests that participants protected with drug prophylaxis are actually safer from malaria than they would be asleep at home [76]. Feeding upon non-human hosts limits malaria transmission [31] but also, creates large gaps in biological coverage of human-targeted interventions like ITNs and IRS [32]. The human blood index remains as important today as it was during the GMEP and can be measured as the proportion of blood meals which are of human origin among samples of resting mosquitoes [30] or inferred using simple models of mosquito host-seeking behaviours parameterized with competitive host choice assays [29, 49] and host census data [29]. Recent advances in the application of quality-assured, community-based (CB) trapping schemes greatly improve the scalability, practicality and affordability of continuous survey [77], so it may now be feasible to continually monitor the influence of behavioural and physiological resistance phenotypes upon malaria vectors and transmission on programmatic scales.

While such entomological parameters can be monitored prospectively, they can only be used to infer the suppression or rebound of malaria vectors and transmission where appropriate retrospective baseline data are also available [4, 32]. Such legacy data are needed to not only allow the frequency of these phenotypes to be compared, but also the population size of each vector taxon which was historically important [8, 9, 11, 20, 25, 45]. Settings with little or no coverage with ITNs or IRS are now becoming increasingly rare and misrepresentative so it has never been more urgent to establish sentinel sites for longitudinal, integrated monitoring of vectors populations and the epidemiological events they mediate. While historical literature and data have significant limitations of scope and methodology, they may nevertheless represent the only representative retrospective view of baseline conditions before the recent roll out of ITNs and IRS in many contexts [5].

A suggested generic plan for strengthening national or regional malaria vector monitoring platforms to incorporate assessment of essential behavioural phenotypes and their influence upon vector control impact, mosquito population dynamics and epidemiological outcomes.

-

1.

Expand and consolidate any existing national network of sentinel surveillance sites for physiological resistance of malaria vector mosquitoes to insecticides, ideally integrating with similar platforms for other common mosquito-borne diseases, such as lymphatic filariasis. Such sites should also overlap both with existing historical entomological study sites for which baseline legacy data is available, and with national platforms for assessing malaria burden through cross-sectional malaria indicator surveys or quality-assured facility-based surveillance.

-

2.

Establish an affordable, practical longitudinal community-based (CB) mosquito trapping scheme [77] with a single sampling cluster [78, 79] at each of sites for physiological resistance surveillance so that the range of seasonal trends in malaria transmission and contributing vectors (including dry-season minima[56, 80]) as well as the impact of national vector control strategies upon these trends can be assessed. Given the diversity of vector species and behaviours across the tropics, this may require initial pilot evaluations to select and calibrate suitable trapping methods or to validate calibrations from elsewhere. Even in Africa, trapping methodologies are poorly standardized [81] and Centers for Disease Control light traps placed beside occupied bednets indoors appear to be the only widely-evaluated exposure-free trapping method with reasonably high relative sensitivity in a diversity of settings [82, 83]. However, even this widely accepted method does not function with satisfactory efficacy in some locations [78] and the only trapping tool that has been successfully applied through affordable, quality-assured CB trapping schemes is the relatively new Ifakara Tent Trap [77] which has only been evaluated in two countries [78, 79].

-

3.

Given the reliance of scalable CB trapping schemes upon essentially unsupervised field-

-

4.

based personnel, it is also essential establish a quality assurance system in which each of these sites is regularly and randomly re-surveyed by a centrally coordinated, specialist entomological team using the same trapping methods. It is essential that the CB personnel are unaware of the re-survey schedule so that the quality of CB sampling assessed is representative of that implemented all year round.

-

5.

Establish experimental hut capacity at one or two of these sentinel sites, chosen so that most nationally-relevant or regionally-relevant vector species are available at useful densities for as much of the year as possible, enabling the efficacy of vector control interventions to be assessed before and after their introduction [18].

-

6.

Incorporate surveys of vector feeding and resting behaviours, using human landing catch by participants protected with drug chemoprophylaxis [76] and backpack aspirator/screening barrier sampling tools [84, 85], respectively, into these quality assurance surveys to quantify the extent to which each important vector species feeds on humans, feeds indoors or rests indoors.

-

7.

Integrate questions relating to relevant human behaviours [5], vector control coverage and livestock ownership into overlapping malaria indicator surveys or, where these do not exist, establish a rolling system of rapid surveys of the human population so that the contributions of vector behaviours, human behaviours and intervention availability to gaps in biological coverage [32] can be quantified.

Abbreviations

- CB:

-

Community-based

- GMEP:

-

Global malaria eradication programme

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- ITN:

-

Insecticide-treated nets

- ITWL:

-

Insecticide-treated wall lining.

References

O’Meara WP, Mangeni JN, Steketee R, Greenwood B: Changes in the burden of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010, 10: 545-555. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70096-7.

Murray CJL, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD: Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2012, 379: 413-431. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8.

Lindblade KA: Does a mosquito bite when no one is around to hear it. Int J Epidemiol. 2013, 42: 247-249. 10.1093/ije/dyt004.

Seyoum A, Sikala C, Chanda J, Chinula D, Ntamatungiro AJ, Hawela M, Miller JM, Russell TL, Briet OJT, Killeen GF: Human exposure to Anopheline mosquitoes occurs primarily indoors, even for users of insecticide-treated nets in Luangwa valley, south-east Zambia. Parasit Vectors. 2012, 5: 101-10.1186/1756-3305-5-101.

Huho B, Briet OJT, Seyoum A, Sikala C, Bayoh N, Gimnig JE, Okumu FO, Diallo D, Abdulla S, Smith T, Killeen GF: Consistently high estimates for proportion of human exposure to malaria vector populations occuring indoors in rural Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2013, 42: 235-247. 10.1093/ije/dys214.

Lounibos P: Competitive displacement and reduction. AMCA Bulletin. 2007, 23: 276-282.

Gillies MT, Smith A: Effect of a residual house spraying campaign on species balance in Anopheles funestus group: the replacement of Anopheles funestus Giles with Anopheles rivulorum Leeson. Bull Entomol Res. 1960, 51: 248-252.

Bayoh MN, Mathias DK, Odiere MR, Mutuku FM, Kamau L, Gimnig JE, Vulule JM, Hawley WA, Hamel MJ, Walker ED: Anopheles gambiae: historical population decline associated with regional distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets in Western Nyanza Province. Kenya. Malar J. 2010, 9: 62-10.1186/1475-2875-9-62.

Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killeen GF: Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011, 10: 80-10.1186/1475-2875-10-80.

Smith A: Malaria in the Taveta region of Kenya and Tanganyika. III. Entomological findings three years after the spraying period. East Afr Med J. 1962, 39: 553-564.

Derua YA, Alifrangis M, Hosea KM, Meyrowitsch DW, Magessa SM, Pedersen EM, Simonsen PE: Change in composition of Anopheles gambiae complex and its possible implications for the transmission of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2012, 11: 188-10.1186/1475-2875-11-188.

Mutuku FM, King CH, Mungai P, Mbogo C, Mwangagi J, Muchiri EM, Walker ED, Kitron U: Impact of insecticide-treated bed nets on malaria transmission indices on the south coast of Kenya. Malar J. 2011, 10: 356-10.1186/1475-2875-10-356.

Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Orindi BO, Muturi EJ, Midega JT, Nzovu J, Gatakaa H, Githure J, Borgemeister C, Keating J, Beier J: Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013, 12: 13-10.1186/1475-2875-12-13.

Ranson H, Nguessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V: Pyrethroid resistance in African anopheline mosquitoes: what are the implications for malaria control?. Trends Parasitol. 2011, 27: 91-98. 10.1016/j.pt.2010.08.004.

Govella NJ, Ferguson H: Why use of interventions targeting outdoor biting mosquitoes will be necessary to achieve malaria elimination. Front Physiol. 2012, 3: 1-5.

Elliott R: The influence of vector behavior on malaria transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972, 21: 755-763.

Pates H, Curtis C: Mosquito behavior and vector control. Ann Rev Entomol. 2005, 50: 53-70. 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130439.

Kitau J, Oxborough RM, Tungu PK, Matowo J, Malima RC, Magessa SM, Bruce J, Mosha FW, Rowland MW: Species shift in Anopheles gambiae complex: do LLINs successful control Anopheles arabiensis?. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e31481-10.1371/journal.pone.0031481.

Molineaux L, Shidrawi GR, Clarke JL, Boulzaguet JR, Ashkar TS: Assessment of insecticidal impact on the malaria mosquito’s vectorial capacity, from data on the man-biting rate and age composition. Bull World Health Organ. 1979, 57: 265-274.

Bugoro H, Iro’ofa C, Mackenzie DO, Apairamo A, Hevalao W, Corcoran S, Bobogare A, Beebe NW, Russell TL, Chen C, Cooper RD: Changes in vector species composition and current vector biology and behaviour will favour malaria elimination in Santa Isabel Province. Solomon Islands Malar J. 2011, 10: 287.

Gillies MT, DeMeillon B: The Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara (Ethiopian zoogeographical region). 1968, Johannesburg: South African Institute for Medical Research

Sharp BL, Le Sueur D: Malaria in South Africa-the past, the present, and selected implications for the future. S Afr Med J. 1996, 86: 83-89.

Hargreaves K, Koekemoer LL, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Mthembu J, Coetzee M: Anopheles funestus resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 14: 181-189. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00234.x.

Russell TL, Beebe NW, Cooper RD, Lobo NF, Burkot TR: Successful malaria elimination strategies require interventions that target changing vector behaviours. Malar J. 2013, 12: 56-10.1186/1475-2875-12-56.

Giglioli G: National-wide malaria eradication projects in the Americas. III. Eradication of Anopheles darlingi from the inhabited areas of British Guiana by DDT residual spraying. J Natl Malar Soc. 1951, 10: 142-161.

Hiwati H, Mitro S, Samjhawan A, Sardjoe P, Soekhoe T, Takken W: Collapse of Anopheles darlingi populations in Suriname after introduction of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs); malaria down to near elimination level. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012, 86: 649-655. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0414.

Crawford JE, Lazzaro BP: The demographic histories of the M and S molecular forms of Anopheles gambiae s.s. Mol Biol Evol. 2010, 27: 1739-1744. 10.1093/molbev/msq070.

Ambrose L, Riginos C, Cooper RD, Leow KS, Ong W, Beebe NW: Population structure, mitochondrial polyphly and the repeated loss of human biting ability in anopheline mosquitoes from the southwest pacific. Mol Ecol. 2012, 21: 4327-4343. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05690.x.

Killeen GF, McKenzie FE, Foy BD, Bogh C, Beier JC: The availability of potential hosts as a determinant of feeding behaviours and malaria transmission by mosquito populations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 95: 469-476. 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90005-7.

Garrett-Jones C: The human blood index of malarial vectors in relationship to epidemiological assessment. Bull World Health Organ. 1964, 30: 241-261.

Kiszewski A, Mellinger A, Spielman A, Malaney P, Sachs SE, Sachs J: A global index representing the stability of malaria transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004, 70: 486-498.

Kiware SS, Chitnis N, Devine GJ, Moore SJ, Majambere S, Killeen GF: Biologically meaningful coverage indicators for eliminating malaria transmission. Biol Lett. 2012, 8: 874-877. 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0352.

Muirhead-Thomson RC: The significance of irritability, behaviouristic avoidance and allied phenomena in malaria eradication. Bull World Health Organ. 1960, 22: 721-734.

Killeen GF, Chitnis N, Moore SJ, Okumu FO: Target product profile choices for intra-domiciliary malaria vector pesticide products: repel or kill. Malar J. 2011, 10: 207-10.1186/1475-2875-10-207.

Bogh C, Pedersen EM, Mukoko DA, Ouma JH: Permethrin-impregnated bed net effects on resting and feeding behaviour of lymphatic filariasis vector mosquitoes in Kenya. Med Vet Entomol. 1998, 12: 52-59. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1998.00091.x.

Moiroux N, Gomez MB, Pennetier C, Elanga E, Djenontin A, Chandre F, Djegbe I, Guis H, Corbel V: Changes in Anopheles funestus biting behavior following universal coverage of long-lasting insecticidal nets in Benin. J Infect Dis. 2012, 206: 1622-1629. 10.1093/infdis/jis565.

Lindsay SW, Parson L, Thomas CJ: Mapping the ranges and relative abundance of the two principle African malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto and An. arabiensis, using climate data. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1998, 265: 847-854. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0369.

Govella NJ, Okumu FO, Killeen GF: Insecticide-treated nets can reduce malaria transmission by mosquitoes which feed outdoors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 82: 415-419. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0579.

Yohannes M, Boelee E: Early biting rhythm in the Afro-tropical vector of malaria, Anopheles arabiensis and challenges for its control in Ethiopia. Med Vet Entomol. 2012, 26: 103-105. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2011.00955.x.

Coluzzi M, Sebatin A, Petrarca V, Di Deco MA: Chromosomal differentiation and adaptation to human environments in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979, 72: 483-498.

Coluzzi M, Sabatin A, Petrarca V, Di Deco MA: Behavioural divergences between mosquitoes with different inversion karyotypes in polymorphic populations of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Nature. 1977, 266: 832-833. 10.1038/266832a0.

Hasan A, Suguri S, Fujimoto C, Itaki RL, Harada M, Kawabata M, Bugoro H, Albino B, Tsukahara T, Hombhanje F, Masta A: Phylogeography and dispersion pattern of Anopheles farauti senso stricto mosquitoes in Melanesia. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008, 46: 792-800. 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.09.018.

Taylor B: Changes in feeding behaviour on malaria vector, Anopheles faraut i Lav., following use of DDT a residual spray in houses in the British Solomon Island Protectorate. Trans R Entomol Soc. 1975, 127: 277-292.

Charlwood JD, Graves PM: The effect of permethrin-impregnated bed nets on a population of Anopheles farauti in coastal Papua New Guinea. Med Vet Entomol. 1987, 1: 319-327. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1987.tb00361.x.

Trape J-F, Tall A, Diagne N, Ndiath O, Ly AB, Faye J, Diaye-Ba F, Roucher C, Bouganali C, Badiane A, Sarr FD, Mazenot C, Toure-Balde A, Raoult D, Druilhe P, Mercereau-puijalon O, Rogier C, Sokhna C: Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of insecticide-treated bednets and artemisinin-based combination therapies: a longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011, 11: 925-932. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70194-3.

Yewhalaw D, Wassie F, Steurbaut W, Spanoghe P, Van Bortel W, Denis L, Tessema DA, Getachew Y, Coosemans M, Duchateau L, Speybroeck : Multiple insecticide resistance: an impediment to insecticide-based malaria vector control program. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e16066-10.1371/journal.pone.0016066.

Reddy MR, Overgaard HJ, Abaga S, Reddy VP, Caccone A, Kiszewski AE, Slotman MA: Outdoor host seeking behaviour of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes following initiation of malaria vector control on Bioko Island. Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2011, 10: 184-10.1186/1475-2875-10-184.

Okumu FO, Mbeyela E, Lingamba G, Moore J, Ntamatungiro AJ, Kavishe DR, Kenward MG, Turner E, Lorenz LM, Moore SJ: Comparative field evaluation of combinations of long-lasting insecticide treated nets and indoor residual spraying, relative to either method alone, for malaria prevention in an area where the main vector is Anopheles arabiensis. Parasit Vectors. 2013, 6: 46-10.1186/1756-3305-6-46.

Torr SJ, Torre A, Calzetta M, Costantin C, Vale GA: Towards a fuller understanding of mosquito behaviour: use of electrocuting grids to compare the odour-oriented responses of Anopheles arabiensis and An.quadriannulatus in the field. Med Vet Entomol. 2008, 22: 93-108. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00723.x.

Russell TL, Lwetoijera DW, Maliti D, Chipwaza B, kihonda J, Charlwood JD, Smith TA, Lengeler C, Mwanyangala MA, Nathan R, Knols BGJ, Takken W, Killeen GF: Impact of promoting longer-lasting insecticide treatment of bed nets upon malaria transmission in a rural Tanzanian setting with pre-existing high coverage of untreated nets. Malar J. 2010, 9: 187-10.1186/1475-2875-9-187.

Curtis C, Mnzava AEP: Comparison of house spraying and insecticide-treated nets for malaria control. Bull World Health Organ. 2000, 78: 1389-1400.

Le Menach A, Takala S, McKenzie FE, Perisse A, Harris A, Flahault A, Smith DL: An elaborated feeding cycle model for reductions in vectorial capacity of night-biting mosquitoes by insecticide-treated nets. Malar J. 2007, 6: 10-10.1186/1475-2875-6-10.

Saul A: Zooprophylaxis or zoopotentiation: the outcome of introducing animals on vector transmission is highly dependent on the mosquito mortality while searching. Malar J. 2003, 2: 32-10.1186/1475-2875-2-32.

Sharp BL, Ridl FC, Govender D, Kuklinski J, Kleinschmidt I: Malaria vector control by indoor residual insecticide spraying on the tropical island of Bioko. Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2007, 6: 52-10.1186/1475-2875-6-52.

Molineaux L, Shidrawi GR, Clarke JL, Boulzaguet R, Ashkar T, Dietz K: The impact of propoxur on Anopheles gambiae s.l. and some other anopheline populations, and its relationship with some pre-spraying variables. Bull World Health Organ. 1976, 54: 379-389.

Killeen GF: A second chance to tackle African malaria vector mosquitoes that avoid houses and don’t take drugs. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013, 88: 809-816.

Corbel V, Akogbeto M, Damien GB, Djenontin A, Chandre F, Rogier C, Moiroux N, Chabi J, Banganna B, Padonou GG, Henry M: Combination of malaria vector control interventions in pyrethroid resistance area in Benin: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012, 12: 617-626. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70081-6.

N’Guessan R, Rowland MW: Indoor residual spraying for prevention of malaria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012, 12: 581-10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70139-1.

Osse R, Aikpon R, Padonou GG, Oussou O, Yadouleton A, Akogbeto M: Evaluation of efficacy of bendiocarb in indoor residual spraying against pyrethroid resistant malaria vectors in Benin: results of the third compaign. Parasit Vectors. 2012, 5: 163-10.1186/1756-3305-5-163.

Garrett-Jones C, Boreham PFL, Pant CP: Feeding habits of anopheline (Diptera:Culidae) in 1971–78, with reference to human blood index: a review. Bull Entomol Res. 1980, 70: 165-185. 10.1017/S0007485300007422.

de Fur PL, Evans GW, Hubal EAC, Kyle AD, Morello-Frosch RA, Williams DR: Vulnerability as a function of individual and group resources in cumulative risk assesment. Environ Health Perspect. 2007, 115: 817-824. 10.1289/ehp.9332.

Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B: The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guideline for future work. Child Develop. 2000, 71: 543-562. 10.1111/1467-8624.00164.

Luthar SS, Cicchetti D: The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Develop Psychopathol. 2000, 12: 857-885. 10.1017/S0954579400004156.

Holling CS: Resilience and stability of ecological system. Ann Rev Ecol Systematics. 1973, 4: 1-23. 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245.

Ferguson HM, Dornhaus A, Beeche A, Borgemeister C, Gottlieb M, Mulla MS, Gimnig JE, Fish D, Killeen GF: Ecology: a prerequisite for malaria elimination and eradication. PLoS Med. 2010, 7: e1000303-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000303.

Sharp BL, Kleinschmidt I, Streat E, Maharaj R, Barnes KI, Durrheim DN, Ridl FC, Morris N, Seocharan I, Kunene S, JJ LAG, Mthembu JD, Maartens F, Martin CL, Barreto A: Seven years of regional malaria control collaboration–Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 76: 42-47.

Price TD, Qvarnstrom A, Irwin DE: The role of phenotypic plasticity in driving genetic evolution. Proc Biol Sci. 2003, 270: 1433-1440. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2372.

Badyaev AV: Stress-induced variation in evolution: from behavioural plasticity to genetic assimilation. Proc Biol Sci. 2005, 272: 877-886. 10.1098/rspb.2004.3045.

Agrawal AA: Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science. 2001, 294: 321-326. 10.1126/science.1060701.

Barbosa S, Hastings IM: The importance of modelling the spread of insecticide resistance in a heterogeneous environment: the example of adding synergists to bed nets. Malar J. 2012, 11: 258-10.1186/1475-2875-11-258.

Kabula B, Tungu PK, Matowo J, Kitau J, Mweya C, Emidi B, Masue D, Sindato C, Malima RC, Minja J, Msangi S, Njau R, Mosha FW, Magesa SM, Kisinza W: Susceptibility status of malaria vectors to insecticides commonly used for malaria control in Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2012, 17: 742-750. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02986.x.

Molineaux L, Gramiccia G: The Garki Project:research on the epidemiology and control of malaria in the Sudan savanna of West Africa. 1980, Geneva: World Health Organization, 311.

Okumu FO, Moore J, Mbeyela E, Sherlock M, Sangusangu R, Ligamba G, Russell TL, Moore SJ: A modified experimental hut design for studying responses of disease-transmitting mosquitoes to indoor interventions: the Ifakara experimental huts. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e30967-10.1371/journal.pone.0030967.

Service MW: Mosquito Ecology: Field Sampling Methods. 1993, London and New York: Elsevier applied Science, 2

Majambere S, Masue D, Mlacha Y, Govella NJ, Magesa SM, Killeen GF: Advantages and limitations of commercially available electrocuting grids for studying mosquito behaviour. Parasit Vectors. 2013, 6: 53-10.1186/1756-3305-6-53.

Gimnig JE, Walker ED, Otieno P, Kosgei J, Olang G, Omboki M, Williamson J, Marwanga D, Abong’o D, Desai M, Kariuki S, Hamel MJ, Lobo NF, Bayoh N: Incidence of malaria among mosquito collectors conducting human landing catches in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013, 88: 301-308. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0209.

Chaki PP, Mlacha Y, Msellem D, Muhili A, malishee AD, Mtema ZJ, Kiware SS, Zhou Y, Lobo NF, Russell TL, Dongus S, Govella NJ, Killeen GF: An affordable, quality-assured community-based system for high-resolution entomological surveillance of vector mosquitoes that reflects human malaria infection risk pattern. Malar J. 2012, 11: 172-10.1186/1475-2875-11-172.

Govella NJ, Chaki PP, Mpangile J, Killeen GF: Monitoring mosquitoes in urban Dar es Salaam: evaluation of resting boxes, window exit traps, CDC light traps, Ifakara tent traps and human landing catches. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4: 40-10.1186/1756-3305-4-40.

Sikala C, Killeen GF, Chanda J, Chinula D, Miller JM, Russell TL, Seyoum A: Evaluation of alternative mosquito sampling methods for malaria vectors in lowland south east Zambia. Parasit Vectors. 2013, in press

Eckhoff PA: Mathematical models of within-host and transmission dynamics to determine effects of malaria interventions in a variety of transmission settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013, 88: 817-827.

Kelly-Hope LA, McKenzie FE: The multiplicity of malaria transmission: a review of entomological inoculation rate measurements and methods across sub-Saharan africa. Malar J. 2009, 8: 19-10.1186/1475-2875-8-19.

Mboera LEG, Kihonda J, Braks MA, Knols BGJ, Braks MA, Knols BG: Short report: influence of centers for disease control light trap position, relative to a human-baited bed net, on catches of Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998, 59: 595-596.

Mboera LEG: Sampling techniques for adult Afrotropical malaria vectors and their reliability in the estimation of entomological inoculation rates. Tanzania Health Res Bull. 2005, 7: 117-124.

Maia MF, Robinson A, John A, Mgando J, Simfukwe E, Moore SJ: Comparison of the CDC Backpack aspirator and the Prokopack aspirator for sampling indoor-and outdoor-resting mosquitoes in southern Tanzania. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4: 124-10.1186/1756-3305-4-124.

Burkot TR, Russell TL, Reimer LJ, Bugoro H, Beebe NW, Cooper RD, Sukawati S, Collins FH, Lobo NF: Barrier screens: a methods to sample blood-fed and host-seeking exophilic mosquitoes. Malar J. 2013, 12: 49-10.1186/1475-2875-12-49.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Fredros Okumu and Dr Tanya Russell for valuable discussions and comments on the manuscript. The research leading to these results has received funding support from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 under grant agreement no 265660 and from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Malaria Transmission Consortium, award number 45114. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NJG and GFK conceived this analysis and review. NJG conducted literature search, drafted the manuscript and edited it based on comments from GFK. PPC and GFK contributed strategies for practical monitoring of mosquito population dynamics on national scales. GFK formulated and implemented the model simulations. All authors agreed to the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Govella, N.J., Chaki, P.P. & Killeen, G.F. Entomological surveillance of behavioural resilience and resistance in residual malaria vector populations. Malar J 12, 124 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-124

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-124