Abstract

Background

Since 1985, amoebic liver abscess (ALA) has been a public health problem in northern Sri Lanka. Clinicians arrive at a diagnosis based on clinical and ultrasonographic findings, which cannot differentiate pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) from ALA. As the treatment and outcome of the ALA and PLA differs, determining the etiological agent is crucial.

Methods

All clinically diagnosed ALA patients admitted to the Teaching Hospital (TH) in Jaffna during the study period were included and the clinical features, haematological parameters, and ultrasound scanning findings were obtained. Aspirated pus, blood, and faecal samples from patients were also collected. Pus and faeces were examined microscopically for amoebae. Pus was cultured in Robinson’s medium for amoebae, and MacConkey and blood agar for bacterial growth. ELISA kits were used for immunodiagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection. DNA was extracted from selected pus samples and amplified using nested PCR and the purified product was sequenced.

Results

From July 2012 to July 2015, 346 of 367 clinically diagnosed ALA patients admitted to Jaffna Teaching Hospital were enrolled in this study. Almost all patients (98.6%) were males with a history of heavy alcohol consumption (100%). The main clinical features were fever (100%), right hypochodric pain (100%), tender hepatomegaly (90%) and intercostal tenderness (60%). Most patients had leukocytosis (86.7%), elevated ESR (85.8%) and elevated alkaline phosphatase (72.3%). Most of the abscesses were in the right lobe (85.3%) and solitary (76.3%) in nature. Among the 221 (63.87%) drained abscesses, 93.2% were chocolate brown in colour with the mean volume of 41.22 ± 1.16 ml. Only four pus samples (2%) were positive for amoeba by culture and the rest of the pus and faecal samples were negative microscopically and by culture. Furthermore, all pus samples were negative for bacterial growth. Antibody against E. histolytica (99.7%) and the E. histolytica antigen were detected in the pus samples (100%). Moreover, PCR and sequencing confirmed these results.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first report from Sri Lanka that provides immunological and molecular confirmation that Entamoeba histolytica is a common cause of liver abscesses in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amoebiasis caused by Entamoeba histolytica, is known to affect at least 50 million people around the world and is responsible for up to 100,000 deaths per annum [1, 2]. Amoebic liver abscess (ALA), the most common extra-intestinal manifestation of invasive amoebiasis, is associated with high morbidity and mortality if the condition is not diagnosed and treated promptly.

The first report of hepatic amoebiasis from Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, dates to 1821 [3]. Since then, reports describing cases from all over the island have been published [3–7]. After about 1975, while many cases of clinically diagnosed ALA have been reported from the northern part of Sri Lanka [8–11], no cases have yet been reported from the rest of the island. Since 1985, clinicians working at Jaffna Teaching Hospital have been treating suspected ALA patients who were usually referred either from private clinics or peripheral Government hospitals [8]. The diagnosis was mainly based on the patient’s history, clinical features and other investigations such as haematological parameters and ultrasonography.

However, it is well known that the clinical features of ALA (acute onset of fever, abdominal pain and hepatomegaly) are very similar to those of pyogenic liver abscess (PLA), as are the ultrasonographic features. Thus, it is difficult to differentiate ALA from PLA either clinically or by ultrasound imaging [12]. At the same time, differentiating between PLA and ALA is important because the treatment regimen is different.

Although antibody-based and molecular diagnostic assays are very sensitive and specific for the confirmation of ALA, the limited resources available at Jaffna Teaching Hospital has meant that none of the patients admitted there have had laboratory confirmation by a specific diagnostic assay. The need to confirm the aetiological agent causing clinically suspected ALA in Jaffna is further highlighted by the fact that most patients had no evidence of intestinal amoebiasis (dysentery).

Hence, this study was carried out to confirm the aetiological agent causing clinically suspected ALA as Entamoeba histolytica, with the aid of specific immunological and molecular tools, for the first time in Sri Lanka.

Methods

Study design

This study was carried out among all adult patients with suspected ALA admitted to the medical wards of Jaffna TH between July 2012 and July 2015.

Data collection

Information on the clinical features, haematological parameters such as full blood count, liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), co-morbid conditions, and ultrasound findings were collected from the bed head ticket (BHT) after obtaining permission from the respective clinicians.

Sample collection

Collection of pus from the abscess

A pus sample was collected while ultrasound guided aspiration was carried out as part of the treatment and management procedure. The total volume and colour of the pus were recorded. The last portion of the pus was collected into a sterile bottle and immediately transported to the Laboratory at the Division of Parasitology, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna for the direct microscopic examination of the smear and culture. An aliquot of pus was stored at -40 °C for further immunological and molecular investigations.

Collection of blood from patients and controls

A sample of 3 ml venous blood was collected from all patients under sterile conditions, before treatment commenced. Control samples were collected from 100 randomly selected, healthy individuals (university students) who had been living for more than 5 years in northern Sri Lanka. Serum was separated from the clotted blood sample by centrifugation at 3500× rpm /10 min and stored at -20 °C for further serological investigations.

Collection of faecal samples

Faecal samples were collected from each patient in sterile, dry containers and transported to the laboratory on the same day. This procedure was repeated for three consecutive days from each patient.

Basic laboratory diagnosis of ALA

Microscopic demonstration of the parasite

Both wet smears and permanent smears stained with trichrome were examined for trophozoites or cysts of E. histolytica in the pus, faecal sample, and in cultures.

Culture of Entamoeba spp.

Parasite culture was performed as per the method described by Robinson [13]. Briefly, freshly collected pus and faecal samples were inoculated separately in Robinson medium and incubated at 37 °C for 48–72 h.

Culture of bacteria

A loop of fresh pus sample was inoculated directly onto the surface of pre-warmed MacConkey and blood agar plates and streaked. The inoculated plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C. Plates were examined after 18–24 h of incubation for the presence of bacterial growth.

Serological investigations

Entamoeba histolytica IgG ELISA

Serum samples stored at -20 °C were thawed and examined for circulating IgG antibody against E. histolytica using an AccuDiag™ E. histolytica IgG (Amoebiasis) ELISA kit (California, USA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Entamoeba histolytica antigen detection ELISA

Pus and serum samples were examined for E. histolytica antigen using an E. histolytica/E. dispar antigen detection ELISA kit from Diagnostic Automation/Cortez Diagnostics, Inc. (California, USA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Molecular diagnosis

DNA was extracted from each pus sample using a QIAGEN stool mini kit (Maryland, USA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

A nested PCR was performed based on the serine-rich E. histolytica protein (SREHP) coding gene of the parasite [14]. Briefly, 2 μl of extracted genomic DNA was used in the primary PCR in a 25 μl reaction using the PCR master mix (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) and the primers, SREHP-5 (5′-GCT AGT CCT GAA AAG CTT GAA GAA GCT G-3′) and SREHP-3 (5′-GGA CTT GAT GCA GCA TCA AGG T-3′). For the secondary reaction, the same 25 μl reaction was prepared though 2 μl of a 1:50 dilution of the initial PCR product was used as template. Also, a second set of nested primers; nSREHP-5 (5′-TAT TAT TAT CGT TAT CTG AAC TAC TTC CTG-3′) and nSREHP-3 (5′-GAA GAT AAT GAA GAT GAT GAA GAT G-3′) was used.

The temperature cycling conditions for the primary PCR amplification included an initial denaturing step, carried out at 94 °C for 15 min. This was followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 1.5 min and 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min. The secondary PCR used the same temperature cycling conditions, with one modification; an annealing temperature of 55 °C [14]. One representative PCR product was purified using commercially purchased QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN), according to the protocol of the manufacturer. The purified PCR product was sequenced bi-directionally using the ABI 3500 Dx capillary instrument (Life Technologies, California, USA) at the Institute of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (IBMBB), University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Analysis of data

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (Version 16). Sequences generated were subjected to BLAST searches against AmoebaDB (http://amoebadb.org/amoeba/).

Results

History and clinical presentation

A total of 346 suspected ALA patients were enrolled in this study from July 2012 to July 2015. Among these patients, almost all (98.6%) were males with a history of consumption of alcohol (100%), especially a local drink, consisting of the fermented sap of the Palmyrah palm (toddy). The predominant clinical features observed were fever, right hypochodric pain with or without abdominal pain (Table 1). All the patients had high swinging fever with the average temperature of 38.9 ± 0.5 °C and the majority (98.26%) complained of fever for more than 5 days. Further, all the patients complained of right hypochodric pain, and a small number of patients (10%) had pain at the right shoulder tip, whereas roughly half of them reported abdominal pain (46.8%). A few of them (27.5%) reported nausea and vomiting. A few reported (7.8%) diarrhoea within the last 6 months, but the diarrhoea they described was of the watery type. Other than 24 patients (6.9%) who identified themselves as diabetic, there was no other significant co-morbidity (Table 1).

Haematological parameters

Most patients had leucocytosis (86.7%), elevated ESR (85.8%) and elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (72.3%). Elevated aspartate transaminase (AST/SGOT) was observed in some patients (37.8%) and slightly elevated in very few (13.6%) (Table 1).

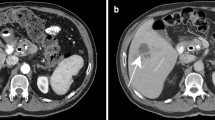

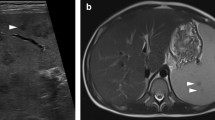

Ultrasound findings

Most of the abscesses (85.3%) were found in the right lobe of the liver whereas 51 were found in the left lobe (Table 1). Most patients (76.3%) had a solitary abscess.

Details of abscess fluid

A total of 221 (63.87%) abscesses were drained within this 3-year period. The pus drained from almost all patients (93.2%) was chocolate brown in colour. The volume of pus varied, but more than 50 ml was drained from 133 abscesses. The average volume of pus drained from all abscesses was 41.22 ± 1.16 ml.

Microscopic examination and the culture of pus samples

Trophozoites of E. histolytica were not observed in any of 221 saline smears prepared from aspirated pus. However, four pus samples (2%) cultured in Robinson’s media were positive for E. histolytica. In addition, all 221 samples were negative for bacterial growth on MacConkey and blood agar.

Microscopic examination and the culture of faecal samples

Only 207 (59.8%) faecal samples were obtained from the patients. Among them, 30% provided three faecal samples, 40% provided two, and remainder gave only one sample. All 207 faecal samples were negative for Entamoeba spp. by microscopic examination and culture in Robinson’s media.

Immunological diagnosis

Of 346 serum samples tested for E. histolytica circulating antigen, 344 were positive (99.4%). All 221 pus samples (100%) collected from patients who were sero-positive for E. histolytica, were positive for E. histolytica antigen (Table 2).

Among the 346 serum samples investigated, 345 were positive (99.7%) for IgG antibody against E. histolytica. Although the one sample which was negative for IgG antibody was positive for circulating Entamoeba antigen.

Moreover, E. histolytica IgG antibodies were negative in 100 serum samples collected from healthy individuals, suggesting that the sensitivity of the test is 100% (345/345) and the specificity is 99.01% (100/101). Further, the positive and negative predictive values of the test were 99.7% (345/346) and 100% (100/100), respectively (Table 3).

PCR diagnosis

Nested PCR was performed on selected DNA samples extracted individually from the pus aspirated from 50 ALA patients. The targeted Entamoeba species DNA sequence was detected in all 50 pus samples (Fig. 1). The 450 bp sequence obtained from the PCR amplicon was subjected to NCBI BLASTn analysis (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; GenBank KX377525) and comparison to sequences available on the Amoeba DB web site (http://amoebadb.org/amoeba/). The sequences generated in this study were 99% similar to corresponding gene sequences of serine-rich E. histolytica protein [SREHP].

Discussion

This is the first report utilising immunological and molecular testing to confirm that E. histolytica is the aetiological agent of liver abscesses in northern Sri Lanka. Currently at the Jaffna TH, ALA is mainly diagnosed based on clinical findings (fever with right hypochondric and/or abdominal pain), history of heavy consumption of alcohol, followed by ultrasonography. This diagnosis is also supported based on a positive response to treatment with metronidazole.

In this study we examine 346 clinically diagnosed cases of ALA admitted to Jaffna TH. All patients complained of fever on admission. In addition, all had right hypochodric pain with or without abdominal pain. Similar presenting features have been reported from many other studies, conducted in Sri Lanka and elsewhere [3, 8–12, 15–24].

Findings on clinical examination were similar to those described previously in Sri Lanka and other Asian countries [15–17]. Haematological findings such as leukocytosis, elevated ESR and ALP were also comparable to those described previously [16–19, 22–27]. To facilitate the diagnosis, laboratory investigations play a major role. In our study, only 2% (4/221) of pus samples were positive in Robinson’s culture media. All pus samples and faecal samples were negative for the presence of E. histolytica microscopically (wet smears in saline as well as trichrome stained smears). Furthermore, all pus samples were negative for bacterial growth indicating that they were sterile and unlikely to be PLA. As the parasite resides in the periphery of the abscess wall, the probability of obtaining the amoeba in pus is very unlikely [28, 29]. Also, ALA may occur many months after the original intestinal infection is cleared. Hence, detecting the parasite in the faecal sample is also unlikely in the absence of concurrent dysentery [28]. Haque et al. reported that the sensitivity of microscopy for detecting amoebae in the pus of ALA as < 20% [29]. Other investigators report similar findings [12, 21, 23, 30].

Since the microscopic and culture methods available for detecting E. histolytica are less sensitive, immunological and molecular techniques are widely used. In Sri Lanka, these techniques have not been used so far to determine the causative agent of liver abscesses in northern Sri Lanka.

Although the detection of specific antibodies to E. histolytica in serum is thought to be highly sensitive for the diagnosis of ALA [31, 32], people with amoebic infection in endemic areas may have been repeatedly exposed to E. histolytica and remain asymptomatic. This situation makes the definitive diagnosis by antibody detection difficult because of the inability to distinguish a previous infection from a current infection. Combining clinical presentation and antigen detection with antibody detection will provide a definitive diagnosis of current infections.

In our study, 99.7% of serum samples were positive for IgG antibody against E. histolytica. These findings are comparable to those of others [33, 34]. Antigen detection ELISA has several significant advantages compared with other methods currently used for the diagnosis of amoebiasis such as microscopy, culture and even antibody detection tests [31]. The presence of detectable antigen in serum and pus indicates an ongoing infection [31]. In our study, 99.4% of serum and 100% of pus samples were positive for E. histolytica antigen. This provides immunological confirmation for the first time, that the clinical diagnosis of ALA by clinicians at Jaffna TH is well supported.

Many laboratories experience difficulties in diagnosing ALA using microscopy, faecal concentrates or culture-based methods and even using antibody detection in the serum in endemic areas. Hence, more sensitive and specific DNA-based detection methods have become popular as a solution to overcome these constraints [31, 35, 36]. Though successful use of PCR for the diagnosis of E. histolytica has been reported in many countries [37–40] no report has been published to date from Sri Lanka.

In our study, we targeted the serine-rich protein-coding gene which has been widely used elsewhere [14, 41–43]. By applying PCR and sequencing PCR amplicons in this study, we confirm Entamoeba histolytica as a common cause of liver abscesses in northern Sri Lanka.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study from Sri Lanka that provides immunological and molecular confirmation that Entamoeba histolytica is a common cause of clinically diagnosed liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka.

Abbreviations

- ALA:

-

Amoebic liver abscess

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- BHT:

-

Bed head ticket

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- PLA:

-

Pyogenic liver abscess

- SREHP:

-

Serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein

References

World Health Organization. World Health Organization/Pan American Health Organization/UNESCO report of a Consultation of Expert on Amoebiasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1997;72:97–9.

Ximenez C, Moran P, Rojas L, Valadez A, Gomez A. Reassessment of the epidemiology of amebiasis: state of the art. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1023–32.

Rajasuriya K, Nagaratnam N. Hepatic amoebiasis in Ceylon. J Trop Med Hyg. 1962;65(7):165–78.

Ramachandran S, Sivalingam S, Perumal JRA. Hepatic amoebiais in Ceylon. J Trop Med Hyg. 1972;75:23–33.

Jayewardene L, Wijaratnam Y. The serological diagnosis of amoebiasis in Ceylon. Pt I. The indirect haemagglutination test (IHAT). Ceylon J Med Sci. 1973;22(1):1–5.

Canagaretna C. Amoebic liver abscess - a clinical study. Ceylon Med J. 1974;19:18–27.

Ramachandran S. The Marcus Fernando memorial oration 1974. Ceylon Med J. 1975;20:69–81.

Sreeharan NMD, Yogeswaran P, Puthrasingam S, Ranjadayalan K, Ganeshamoorthy J. Hepatic amoebiasis in Northern Sri Lanka: a retrospective study. Jaffna Med J. 1985;20(2):69–74.

Fernando K, Fernando R, Kandasami A, Jude R, Fernando N, Tennakoon S. SP6-3 Fermented sap of spiky Palmyra toddy (Borassus flabellifer) suggested as a vehicle of transportation of amoebiasis in the district of Mannar, Sri Lanka: 50 cases of amoebic liver abscess within 15 months. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2011;65(1):455.

Janani T, Pushpana P, Surenthirakumaran R, Kumanan T, Kannanthasan S. Amoebic liver abscess: An emerging threat in northern Sri Lanka. EMBO global lecture course and symposium on amoebiasis: Exploring the biology and pathogenesis of Entamoeba. Khajuraho, India; 2011. p 80.

Kannathasan S, Iddawala WMDR, De Silva NR, Haque R. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards liver abscess among patients admitted to the teaching hospitals, Jaffna. In: Proceedings of the Peradeniya Univ. International Research Sessions, Sri Lanka, vol. 18. 2014. p. 355.

Salles JM, Moraes LA, Salles MC. Hepatic amebiasis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2003;7(2):96–110.

Robinson GL. Laboratory diagnosis of some human parasitic amoeba. J Gen Microbiol. 1968;53:69–79.

Ayeh-Kumi PF, Ali IM, Lockhart LA, Gilchrist CA, Petri WA, Haque R. Entamoeba histolytica: genetic diversity of clinical isolates from Bangladesh as demonstrated by polymorphisms in the serine-rich gene. Exp Parasitol. 2001;99(2):80–8.

Alam F, Salam MA, Hassan P, Mahmood I, Kabir M, Haque R. Amebic liver abscess in northern region of Bangladesh: sociodemographic determinants and clinical outcomes. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):625.

Bhatti AB, Ali F, Satti SA, Satti TM. Clinical and pathological comparison of pyogenic and amoebic liver abscesses. Adv Infect Dis. 2014;4:117–23.

Chaudhary S, Noor MT, Jain S, Kumar R, Thakur BS. Amoebic liver abscess: a report from central India. Trop Doct. 2015. doi:10.1177/0049475515592283.

Siddiqui MA, Ahad MA, Ekram AS, Islam QT, Hoque MA, Masum QAAI. Clinico-pathological profile of liver abscess in a teaching hospital. TAJ: J Teachers Assoc. 2008;21(1):44–9.

Vallois D, Epelboin L, Touafek F, Magne D, Thellier M, Bricaire F, ALA-PCR Working Group. Amebic liver abscess diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction in 14 returning travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(6):1041–5.

Wuerz T, Kane JB, Boggild AK, Krajden S, Keystone JS, Fuksa M, Anderson J. A review of amoebic liver abscess for clinicians in a nonendemic setting. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;26(10):729–33.

van Hal SJ, Stark DJ, Fotedar R, Marriott D. Amoebiasis: current status in Australia. Med J Aust. 2007;186(8):412.

Cordel H, Prendki V, Madec Y, Houze S, Paris L, Caumes E, et al. Imported amoebic liver abscess in France. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(8):e2333.

Nari GA, Ceballos ER, Carrera LDGS, Preciado VJ, Cruz VJ, Briones RJ, Góngora OJ. Amebic liver abscess. Three years’ experience. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100(5):268–72.

Albenmousa A, Sanai FM, Singhal A, Babatin MA, AlZanbagi AA, Al-Otaibi MM, Bzeizi KI. Liver abscess presentation and management in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom. Ann of Saudi Med. 2011;31(5):528.

Cosme A, Ojeda E, Zamarreño I, Bujanda L, Garmendia G, Echeverría MJ, Benavente J. Pyogenic versus amoebic liver abscesses. A comparative clinical study in a series of 58 patients. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102(2):90–5.

Lodhi S, Sarwari AR, Muzammil M, Salam A, Smego RA. Features distinguishing amoebic from pyogenic liver abscess: a review of 577 adult cases. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(6):718–23.

Ghosh S, Sharma S, Gadpayle AK, Gupta HK, Mahajan RK, Sahoo R, Kumar N. Clinical, laboratory, and management profile in patients of liver abscess from northern India. J Trop Med. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/142382.

Bruckner DA. Amebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5(4):356–69.

Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri Jr WA. Amebiasis. N Eng J Med. 2003;348(16):1565–73.

Blessmann J, Van Pham L, Anthon Nu P, Duong Thi H, Muller-Myhsok B, et al. Epidemiology of amoebiasis in a region of high incidence of amoebic liver abscess in central Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66(5):578–83.

Tanyuksel M, William Jr AP. Laboratory diagnosis of amoebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(4):713–29.

Knobloch J, Mannweiler E. Development and persistence of antibodies to Entamoeba histolytica in patients with amebic liver abscess: Analysis of 216 cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:727–32.

Kraoul LH, Adjmi V, Lavarde JF, Pays C, Tourte-Schaefer C, Hennequin C. Evaluation of a rapid enzyme immunoassay for diagnosis of hepatic amoebiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1530–2.

Mathur S, Gehlot RS, Mohta A, Bhargava N. Clinical profile of amoebic liver abscess. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2002;3:367–73.

Paul J, Srivastava S, Bhattacharya S. Molecular methods for diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica in a clinical setting: An overview. Exp Parasitol. 2007;116:35–43.

Stensvold CR, Lebbad M, Verweij JJ. The impact of genetic diversity in protozoa on molecular diagnostics. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27(2):53–8.

Acuna-Soto R, Samuelson J, De Girolami P, Zarate L, Millan-Velasco F, Schoolnick G, Wirth D. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to the epidemiology of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Entamoeba histolytica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48(1):58–70.

Britten D, Wilson SM, McNerney R, Moody AH, Chiodini PL, Ackers JP. An improved colorimetric PCR-based method for detection and differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in feces. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(5):1108–11.

Zaman S, Khoo J, Ahmed SW, Ng R, Khan MA, Hussain R, Zaman V. Direct amplification of Entamoeba histolytica DNA from amoebic liver abscess pus using polymerase chain reaction. Parasitol Res. 2000;86:724–8.

Khan U, Mirdha BR, Samantaray JC, Sharma MP. Detection of Entamoeba histolytica using polymerase chain reaction in pus samples from amoebic liver abscess. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25(2):55–7.

Fotedar R, Stark D, Beebe N, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for Entamoeba species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(3):511–32.

Haghighi A, Kobayashi S, Takeuchi T, Masuda G, Nozaki T. Remarkable genetic polymorphism among Entamoeba histolytica isolates from a limited geographic area. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(11):4081–90.

Simonishvili S, Tsanava S, Sanadze K, Chlikadze R, Miskalishvili A, Lomkatsi N, et al. Entamoeba histolytica: the serine-rich gene polymorphism-based genetic variability of clinical isolates from Georgia. Exp Parasitol. 2005;110(3):313–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants (patients and volunteers) of this study, the Director, all the consultants, clinicians, Medical Officers, and nursing staff attached to the Teaching hospital, Jaffna for their permission and assistance to carry out this study. Further, they wish to thank Dr. S. Ketheeswary and Dr. S. Pathmini, Radiologists, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna who provided the aspirated pus sample.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the HRD program of HETC project (JFN /O-Med/ N8) by the World Bank

Availability of data and material

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The sequence is submitted in the GenBank database under accession number KX377525.

Authors’ contribution

SK, AM, NRS, DI and RH conceived the study. SK and AM performed the laboratory investigations, SK and TK involved in the data and sample collection. NR did analysis. SK, AM and NRS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna. Permission to carry out this study was obtained from the Director, TH, Jaffna and written consent was obtained from the participants after explaining the purpose and the nature of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kannathasan, S., Murugananthan, A., Kumanan, T. et al. Amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka: first report of immunological and molecular confirmation of aetiology. Parasites Vectors 10, 14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1950-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1950-2