Abstract

Background

Theileria annae is a tick-transmitted small piroplasmid that infects dogs and foxes in North America and Europe. Due to disagreement on its placement in the Theileria or Babesia genera, several synonyms have been used for this parasite, including Babesia Spanish dog isolate, Babesia microti-like, Babesia (Theileria) annae, and Babesia cf. microti. Infections by this parasite cause anemia, thrombocytopenia, and azotemia in dogs but are mostly subclinical in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Furthermore, high infection rates have been detected among red fox populations in distant regions strongly suggesting that these canines act as the parasite’s natural host. This study aims to reassess and harmonize the phylogenetic placement and binomen of T. annae within the order Piroplasmida.

Methods

Four molecular phylogenetic trees were constructed using a maximum likelihood algorithm based on DNA alignments of: (i) near-complete 18S rRNA gene sequences (n = 76 and n = 93), (ii) near-complete and incomplete 18S rRNA gene sequences (n = 92), and (iii) tubulin-beta gene sequences (n = 32) from B. microti and B. microti-related parasites including those detected in dogs and foxes.

Results

All phylogenetic trees demonstrate that T. annae and its synonyms are not Theileria parasites but are most closely related with B. microti. The phylogenetic tree based on the 18S rRNA gene forms two separate branches with high bootstrap value, of which one branch corresponds to Babesia species infecting rodents, humans, and macaques, while the other corresponds to species exclusively infecting carnivores. Within the carnivore group, T. annae and its synonyms from distant regions segregate into a single clade with a highly significant bootstrap value corroborating their separate species identity.

Conclusion

Phylogenetic analysis clearly shows that T. annae and its synonyms do not pertain to Theileria and can be clearly defined as a separate species. Based on the facts that T. annae and its synonyms have not been shown to have a leukocyte stage, as expected in Theileria, do not infect humans and rodents as B. microti, and cluster phylogenetically as a separate species, this study proposes to name this parasite Babesia vulpes sp. nov., after its natural host, the red fox V. vulpes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

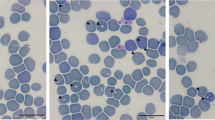

Babesia and Theileria are tick-borne intracellular parasites that infect a variety of vertebrate hosts. Both, Babesia and Theileria, belong to the phylum Apicomplexa, class Piroplasmea, and order Piroplasmida. Despite their morphological resemblances and their similar intraerythrocytic life stage in the vertebrate host, they differ by a main characteristic feature of a pre-erythrocytic life stage in leukocytes found in Theileria but not in Babesia. Several species of piroplasmids infect domestic dogs and wild canines [1]. A relatively recent addition to the species of these genera was a small piroplasmid initially reported in a sick dog from Spain and shown to be most closely related with Babesia microti by phylogenetic analysis, for which it was first referred to as Babesia microti-like species [2]. Based on the observation that this pathogen did not segregate with Babesia parasites belonging to the Babesia sensu stricto group (reviewed in Schnittger et al. [3]), Zahler et al. [2] concluded that it belongs to the genus Theileria and proposed it to be named Theileria annae after the name of the corresponding author’s dog [2,4]. Shortly after its description, this pathogen was shown to cause severe disease with anemia, thrombocytopenia, and azotemia in 157 dogs from the Galicia region in northwestern Spain [5] and has since then been identified as a cause of infection and/or disease in dogs in other areas of northern Spain, Portugal, Croatia, Sweden, and USA [6-10].

Infection of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) by T. annae was first recorded in Spain in 2003 [11] and subsequently in Italy, Croatia, Canada, USA, Portugal, Germany, and Austria [12-18]. Additionally, grey foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) from the USA were also reported to be infected with T. annae [15]. The prevalence of infection found in red fox populations was often high with positive detection in 39% (50/127), 46% (121/261), 50% (18/26), and 69% (63/91) of foxes sampled in North America, Germany, Austria, and Portugal, respectively [15-18]. This is in contrast to the sporadic nature of domestic dog infection where only low prevalence rates comprising of single dogs were found in population surveys [7,10]. The observed high prevalence of T. annae infections of red foxes from different regions, with one exception from northern Italy [19], as well as the fact that they do not seem to cause severe disease in these animals have prompted scientists to suggest that red foxes are the natural reservoirs of this pathogen and a source for domestic dog infection [16-18,20]. DNA sequences of T. annae from foxes published to date or deposited in GenBank and as yet unpublished, are included in Additional file 1: Table S1.

The modes of transmission and tick vectors of T. annae have not been determined. It has been suggested that the hedgehog tick Ixodes hexagonus is a vector of this parasite, based on a survey of tick infestation of infected and uninfected dogs in northwestern Spain [21]. However, no transmission studies to corroborate this suspicion have been published. Furthermore, T. annae infection has been detected in areas where this tick species has not been reported [15]. T. annae DNA has been detected in several tick species including I. hexagonus, I. ricinus [17,22], I. canisuga [17], and Rhipicephalus sanguineus [23]. However, these findings do not provide positive proof for the capacity of these ticks to act as competent vectors for the parasite. On the other hand, they might suggest that the parasite can be transmitted by different tick species, as has been observed for other piroplasmids [3,24]. It has been suggested that other non-vectorial modes of natural transmission described for canine Babesia species, including transplacental transmission and direct infection by dog bites, as in the case of Babesia gibsoni [1,25], can also be valid for T. annae [15].

Since there is disagreement on the placement of T. annae within the Theileria genus [26], it has been named in different ways in a variety of publications. Synonyms of T. annae include Babesia Spanish dog isolate [10], Babesia-microti-like [2,15], Babesia annae [27,28], Babesia (Theileria) annae [14], and Babesia cf. microti [29]. In order to avoid ongoing confusion associated with the use of multiple names, the aim of this study was to: (i) reevaluate the placement of T. annae in the order Piroplasmida, and to (ii) rename it as to reflect its independent species status.

Methods

A BLASTn search was carried out to identify and subsequently download all B. microti and B. microti-related 18S rRNA gene sequences available in Genbank. Over 130 sequences were identified from which those that showed indications of sequence mistakes, or found to be too short to result in a relevant phylogenetic signal as judged by low bootstrap values during a preliminary analysis, were discarded. The remaining sequences were subjected to alignment using MUSCLE [30]. The analysis involved 76 18S rRNA nucleotide sequences of which all positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated resulting in a total of 1,522 positions in the final dataset. After estimation of the shape parameter [31], the T92 + G + I model was applied to infer the tree. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the MEGA6 software [32].

Results

Figure 1 shows a phylogenetic tree based on all available near-complete sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of T. annae and its synonyms, B. microti-related parasites, and all other related piroplasmid species of Clade I as defined in Schnittger et al. [3]. The tree branches into a group of Babesia sp. infecting rodents, macaque, and humans (often referred to as B. microti) and Babesia spp. that infect carnivores (often referred to as B. microti-related). Within the latter group, T. annae and related sequences derived from canines in Asia (Israel), Europe (Spain), and the USA, segregate with a highly significant bootstrap value into a single clade that defines the species Babesia vulpes sp. nov.

Phylogenetic tree of near-complete 18S rRNA gene sequences of T. annae , B. microti , and B. microti -related parasites using maximum likelihood. The sequence of each isolate is labeled with its gene accession number, isolate designation, host, and geographic origin of isolation. The bootstrap values based on 1,000 replicates are displayed next to the branches. The tree is rooted using closely related Babesia parasites infecting rodents and carnivores of Clade I as defined in Schnittger et al. [3]. Wherever applicable, the number of pooled sequences is given. Accession number of pooled sequences are Babesia rodhaini: M87565, DQ641423, AB049999; Babesia sp. leopard [50]: JQ861967, JQ861965, JQ861972; Babesia leo: AY452708, AF244911; Babesia felis: AY452698, AY452699, AY452700, AY452700, AY452701, AY452702, AY452703, AY452704, AY452705, AY452706, AY452707. Babesia sp. baboon: GQ225744 [51] and Babesia sp. caracal AF244913, AF244914 [52]. Clades marked by brackets display a highly significant bootstrap value (≥85). The evolutionary distance is shown in the units of the number of base substitutions per site.

In order to explicitly demonstrate different placement of T. annae and Theileria sp., a phylogenetic tree was generated following the procedure above yet including 17 relevant Theileria sp. sequences that belong to Clade V (Theileria sensu strictu), Clade IV (Theileria equi), and Clade IIIa (Theileria youngi and Theileria bicornis) as defined in Schnittger et al. [3] (Figure 2). Importantly, all Theileria sequences were found to segregate with a highly significant bootstrap into a different clade from Babesia sequences of Clade I, which contained also Babesia vulpes sp. nov.

Phylogenetic tree of near-complete 18S rRNA gene sequences of T. annae , Theileria sp., B. microti , and B. microti -related parasites using maximum likelihood. The sequence of each isolate is labeled with its gene accession number, isolate designation, host, and geographic origin of isolation. The bootstrap values based on 1,000 replicates are displayed next to the branches. The tree is rooted using Cardiosporidium cionae as outgroup [3]. Wherever applicable, the number of pooled sequences is given. Accession number of pooled sequences are Babesia rodhaini: M87565, DQ641423, AB049999; Babesia sp. leopard [50]: JQ861967, JQ861965, JQ861972; Babesia leo: AY452708, AF244911; Babesia felis: AY452698, AY452699, AY452700, AY452700, AY452701, AY452702, AY452703, AY452704, AY452705, AY452706, AY452707. Babesia sp. baboon: GQ225744 [51] and Babesia sp. caracal AF244913, AF244914 [52]. Clades marked by brackets display a highly significant bootstrap value (≥85). The clade of Babesia sp. infecting rodents, macaque, and human has been collapsed. The evolutionary distance is shown in the units of the number of base substitutions per site.

To test the affiliation of additional incomplete T. annae-sequences present in the database with the above defined B. vulves sp. nov. clade, an additional phylogenetic analysis was carried out (Additional file 2: Figure S1). To this end, 18S rRNA gene sequences of the same samples were used to construct the tree, but in addition other available T. annae and T. annae-related incomplete gene sequences were included. Importantly, a similar tree topology was observed as in the tree presented in Figure 1. Although, the clade of T. annae and T. annae-related sequences and its sister clade of Babesia sp. 2 raccoon isolates could not be distinguished by significant bootstraps, all incomplete and near-complete T. annae and T. annae-related sequences joined again into a single clade strongly suggesting their species identity.

A phylogenetic tree of all available near-complete tubulin-beta gene sequences of piroplasmids including a single available T. annae sequence is displayed in Additional file 3: Figure S2. The tree demonstrates that the T. annae sequence is distinct from those of Theileria parasites as it clusters significantly separately and distantly from Theileria species such as Theileria orientalis and Theileria parva. Furthermore, T. annae does not cluster with B. microti infecting rodents and humans but clusters with a Babesia species infecting skunks in the clade of Babesia infecting carnivores.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to harmonize the phylogenetic placement of T. annae with its taxonomic nomenclature. In order to reevaluate the classification of T. annae into the genus Theileria, it is important to analyze the context that led to this notion in the original study describing this parasite. Zahler et al. [2] based their study assumption on a phylogenetic analysis consisting of 18S rRNA gene sequences of some Babesia parasites belonging to the Babesia sensu stricto group, of B. microti and Babesia rodhaini from the Babesia sensu lato group, and of Theileria equi, which was thought to be a Theileria parasite at that time [4,33-35]. However, it has only recently been demonstrated that T. equi belongs to an additional distinct group within the piroplasmid order (corresponding to Clade IV in Schnittger et al. [3]), a finding that has been subsequently confirmed based on the T. equi genome sequence [36]. Thus, Zahler et al. [2] did not include a sequence of a relevant Theileria parasite (corresponding to Clade V in Schnittger et al. [3]) in their analysis. Therefore, the 18S rRNA gene sequence of T. annae segregated as a relative of B. microti into a clade with T. equi, letting them assume that the parasite is related to the genus Theileria. Since then, in a considerable number of subsequent studies on Babesia and Theileria phylogeny, sequences of relevant Theileria parasites have been included, and it has been clearly demonstrated that T. annae sequences do not segregate with those of Theileria parasites but they are rather closely related to those of B. microti [3,26,37-42]. These studies, as well as our results, demonstrate that T. annae is not a Theileria parasite (defined as Clade V in Schnittger et al. [3]) but a parasite most closely related to B. microti [40] (Figure 2).

In an early pioneering study, Goethert and Telford [43] evaluated piroplasms from a range of carnivores and rodents and demonstrated that B. microti is an entity that seems to comprise different species. Extending their work, a number of investigators have evaluated additional piroplasmids and corroborated the existence of at least five different species lineages in this group as based on molecular phylogeny, gene structure analysis, and tick-transmission studies [3,44-46]. In accordance with its tree placement that distinguishes it from zoonotic B. microti parasites, T. annae has never been implicated as cause of human infection.

The phylogenetic tree of near-complete 18S rRNA sequences from our study depicted in Figure 1 shows that T. annae segregates to form an independent and distinct clade. In several studies, relatively short amplicon fragments of the 18S rRNA gene have been sequenced to identify T. annae parasites and deposited in GenBank (Additional file 1: Table S1). In order to verify their tree placement, an additional tree was constructed based on a correspondingly shorter alignment (Additional file 2: Figure S1). This tree virtually confirms the findings shown in Figure 1 and also displays a clade that comprises all 18S rRNA genes of T. annae and synonyms demonstrating the species identity of these isolates. However, the T. annae clade cannot be significantly differentiated from that of Babesia sp. 2 raccoon, South Korean isolates, highlighting the importance of sequencing the complete 18S rRNA gene to enhance the phylogenetic signal, and thus ensure the differentiation into clades supported by a significant bootstrap in this group of parasites.

Most phylogenetic studies on T. annae were performed with the 18S rRNA gene, but the tubulin-beta gene likewise supports the evidence that T. annae is not related to Theileria parasites (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Furthermore, the tubulin-beta tree demonstrates that T. annae does not belong to B. microti which infects rodents and humans but to a separate group of Babesia infecting carnivores. In addition to the genetic evidence, no description has been made of a pre-erythrocytic leukocyte stage of T. annae, which is considered a prerequisite for inclusion in the genus Theileria [33,34].

Thus, phylogenetic analysis clearly shows that T. annae and its synonyms are a single and distinct species as demonstrated by the high genetic identity of 18S rRNA genes from isolates originating from widespread geographic regions (Figure 1, Additional file 2: Figure S1) [2-6,10-16,18-20,47-49]. Since the red fox has been considered as the natural host/reservoir of T. annae, we propose to name this parasite B. vulpes sp. nov., after the red fox species name V. vulpes.

Interestingly, piroplasmids isolated from raccoons from South Korea (Babesia sp. 1 raccoon, South Korea) represent a sister clade of B. vulpes sp. nov. Other Babesia isolates identified in wild raccoons from Japan clearly represent a different species (Babesia sp. 1 raccoon, Japan) from those that have been identified in wild raccoons from South Korea (Babesia sp. 2 raccoon, South Korea), suggesting that these species might have a mutually exclusive endemicity. Noteworthy, a Babesia sp. from a fox in Austria segregates with Babesia sp. 2 raccoon from South Korea, suggesting that there may be an additional Babesia species infecting foxes besides B. vulpes sp. nov.

Conclusions

This phylogenetic analysis confirms that T. annae does not belong to the genus Theileria and that it can be clearly distinguished from B. microti infecting rodents, macaques, and humans. These findings correspond with known biological characteristics as a pre-erythrocytic stage has not been demonstrated for T. annae and the parasite has been exclusively found to infect canines, namely foxes and dogs. Therefore, we conclude that it is a separate distinct species and propose it to be named B. vulpes sp. nov. The renaming of T. annae as B. vulpes sp. nov. should replace the use of synonyms like B. microti-like, Babesia cf. microti, B. annae, and Babesia Spanish dog isolate, prevent the current confusion to facilitate coherent scientific communication, and distinguish this parasite clearly from Theileria by giving it its deserved species status. In accordance with section 8.5 of the ICZN’s International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, details of the new species have been submitted to ZooBank with the life science identifier (LSID) zoobank.org:act:42884D09-A8A4-4679-BA5B-7643269C5FBF.

References

Solano-Gallego L, Baneth G. Babesiosis in dogs and cats – expanding parasitological and clinical spectra. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181:48–60.

Zahler M, Rinder H, Schein E, Gothe R. Detection of a new pathogenic Babesia microti-like species in dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2000;89:241–8.

Schnittger L, Rodriguez AE, Florin-Christensen M, Morrison D. Babesia: A world emerging. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1788–809.

Mehlhorn H, Schein E. The piroplasms: life cycle and sexual stages. Adv Parasitol. 1984;23:37–103.

Camacho AT, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Guitián FJ, Olmeda AS, Goethert HK, et al. Infection of dogs in north-west Spain with a Babesia microti-like agent. Vet Rec. 2001;149:552–5.

Tabar MD, Francino O, Altet L, Sánchez A, Ferrer L, Roura X. PCR survey of vector borne pathogens in dogs living in and around Barcelona, an area endemic for leishmaniasis. Vet Rec. 2009;164:112–6.

Beck R, Vojta L, Mrljak V, Marinculić A, Beck A, Zivicnjak T, et al. Diversity of Babesia and Theileria species in symptomatic and asymptomatic dogs in Croatia. Int J Parasitol. 2009;9:843–8.

Simões PB, Cardoso L, Araújo M, Yisaschar-Mekuzas Y, Baneth G. Babesiosis due to the canine Babesia microti-like small piroplasm in dogs-first report from Portugal and possible vertical transmission. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:50.

Falkenö U, Tasker S, Osterman-Lind E, Tvedten HW. Theileria annae in a young Swedish dog. Acta Vet Scand. 2013;55:50.

Yeagley TJ, Reichard MV, Hempstead JE, Allen KE, Parsons LM, White MA, et al. Detection of Babesia gibsoni and the canine small Babesia ‘Spanish isolate’ in blood samples obtained from dogs confiscated from dog fighting operations. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235:535–9.

Criado-Fornelio A, Martinez-Marcos A, Buling-Saraña A, Barba-Carretero JC. Molecular studies on Babesia, Theileria and Hepatozoon in southern Europe. Part I. Epizootiological aspects. Vet Parasitol. 2003;113:189–201.

Tampieri MP, Galuppi R, Bonoli C, Cancrini G, Moretti A, Pietrobelli M. Wild ungulates as Babesia hosts in northern and central Italy. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:667–74.

Dezdek D, Vojta L, Curković S, Lipej Z, Mihaljević Z, Cvetnić Z, et al. Molecular detection of Theileria annae and Hepatozoon canis in foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Croatia. Vet Parasitol. 2010;172:333–6.

Clancey N, Horney B, Burton S, Birkenheuer A, McBurney S, Tefft K. Babesia (Theileria) annae in a red fox (Vulpes vulpes) from Prince Edward Island, Canada. J Wildl Dis. 2010;46:615–21.

Birkenheuer AJ, Horney B, Bailey M, Scott M, Sherbert B, Catto V, et al. Babesia microti-like infections are prevalent in North American foxes. Vet Parasitol. 2010;172:179–82.

Cardoso L, Cortes HC, Reis A, Rodrigues P, Simões M, Lopes AP, et al. Prevalence of Babesia microti-like infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Portugal. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:90–5.

Najm NA, Meyer-Kayser E, Hoffmann L, Herb I, Fensterer V, Pfister K, et al. A molecular survey of Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and their ticks from Thuringia, Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:386–91.

Duscher G, Fuehrer HP, Kübber-Heiss A. Fox on the run – molecular surveillance of fox blood and tissue for the occurrence of tick-borne pathogens in Austria. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:521.

Zanet S, Trisciuoglio A, Bottero E, de Mera IG, Gortazar C, Carpignano MG, et al. Piroplasmosis in wildlife: Babesia and Theileria affecting free-ranging ungulates and carnivores in the Italian Alps. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:70.

Farkas R, Takács N, Hornyák A, Nachum-Biala Y, Hornok S, Baneth G. First report on Babesia cf. microti infection of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Hungary. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:55.

Camacho AT, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Guitián FJ, Olmeda AS, Telford SR, et al. Ixodes hexagonus is the main candidate as vector of Theileria annae in northwest Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2003;112:157–63.

Lledó L, Giménez-Pardo C, Domínguez-Peñafiel G, Sousa R, Gegúndez MI, Casado N, et al. Molecular detection of hemoprotozoa and Rickettsia species in arthropods collected from wild animals in the Burgos Province, Spain. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:735–8.

Iori A, Gabrielli S, Calderini P, Moretti A, Pietrobelli M, Tampieri MP, et al. Tick reservoirs for piroplasms in central and northern Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170:291–6.

Gou H, Guan G, Liu A, Ma M, Chen Z, Liu Z, et al. Coevolutionary analyses of the relationships between piroplasmids and their hard tick hosts. Ecol Evol. 2013;3:2985–93.

Jefferies R, Ryan UM, Jardine J, Broughton DK, Robertson ID, Irwin PJ. Blood, Bull Terriers and Babesiosis: further evidence for direct transmission of Babesia gibsoni in dogs. Aust Vet J. 2007;85:459–63.

Criado-Fornelio A, Martinez-Marcos A, Buling-Saraña A, Barba-Carretero JC. Molecular studies on Babesia, Theileria and Hepatozoon in southern Europe. Part II. Phylogenetic analysis and evolutionary history. Vet Parasitol. 2003;114:173–94.

Camacho AT, Guitian FJ, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Olmeda S, Goethert H, et al. Serum protein response and renal failure in canine Babesia annae infection. Vet Res. 2005;36:713–22.

Camacho AT. Do eosinophils have a role in the severity of Babesia annae infection? Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:281–2.

Karbowiak G, Majláthová V, Hapunik J, Pet’ko B, Wita I. Apicomplexan parasites of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in northeastern Poland. Acta Parasitol. 2010;55:210–4.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7.

Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G + C-content biases. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:678–87.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9.

Mehlhorn H, Schein E, Ahmed JS. Theileria. In: Kreier JP, editor. Parasitic protozoa, vol. 7. Sand Diego: Academic Press; 1994. p. 217–304.

Kakoma I, Mehlhorn M. Babesia of domestic animals. In: Kreier JP, editor. Parasitic Protozoa, vol. 7. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. p. 141–216.

Mehlhorn H, Schein E. Redescription of Babesia equi Laveran, 1901 as Theileria equi Mehlhorn, Schein 1998. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:467–75.

Kappmeyer LS, Thiagarajan M, Herndon DR, Ramsay JD, Caler E, Djikeng A, et al. Comparative genomic analysis and phylogenetic position of Theileria equi. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:603.

Criado-Fornelio A, Gónzalez-del-Río MA, Buling-Saraña A, Barba-Carretero JC. The “expanding universe” of piroplasms. Vet Parasitol. 2004;119:337–45.

Gray JS. Identity of the causal agents of human babesiosis in Europe. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296 Suppl 40:131–6.

Lack JB, Reichard MV, Van Den Bussche RA. Phylogeny and evolution of the Piroplasmida as inferred from 18S rRNA sequences. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:353–63.

Sivakumar T, Hayashida K, Sugimoto C, Yokoyama N. Evolution and genetic diversity of Theileria. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;27:250–63.

Reichard MV, Van Den Bussche RA, Meinkoth JH, Hoover JP, Kocan AA. A new species of Cytauxzoon from Pallas’ cats caught in Mongolia and comments on the systematics and taxonomy of piroplasmids. J Parasitol. 2005;91:420–6.

Birkenheuer AJ, Whittington J, Neel J, Large E, Barger A, Levy MG, et al. Molecular characterization of a Babesia species identified in a North American raccoon. J Wildl Dis. 2006;42:375–80.

Goethert HK, Telford 3rd SR. What is Babesia microti? Parasitology. 2003;127:301–9.

Nakajima R, Tsuji M, Oda K, Zamoto-Niikura A, Wei Q, Kawabuchi-Kurata T, et al. Babesia microti-group parasites compared phylogenetically by complete sequencing of the CCTeta gene in 36 isolates. J Vet Med Sci. 2009;71:55–68.

Fujisawa K, Nakajima R, Jinnai M, Hirata H, Zamoto-Niikura A, Kawabuchi-Kurata T, et al. Intron sequences from the CCT7 gene exhibit diverse evolutionary histories among the four lineages within the Babesia microti-group, a genetically related species complex that includes human pathogens. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011;64:403–10.

Zamoto-Niikura A, Tsuji M, Qiang W, Nakao M, Hirata H, Ishihara C. Detection of two zoonotic Babesia microti lineages, the Hobetsu and U.S. lineages, in two sympatric tick species, Ixodes ovatus and Ixodes persulcatus, respectively, in Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3424–30.

Criado-Fornelio A, Rey-Valeiron C, Buling A, Barba-Carretero JC, Jefferies R, Irwin P. New advances in molecular epizootiology of canine hematic protozoa from Venezuela, Thailand and Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2007;144:261–9.

Gimenez C, Casado N, Criado-Fornelio A, de Miguel FA, Dominguez-Peñafiel G. A molecular survey of Piroplasmida and Hepatozoon isolated from domestic and wild animals in Burgos (northern Spain). Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:147–50.

Hodžić A, Alić A, Fuehrer H-P, Harl J, Wille-Piazzai W, Duscher G. A molecular survey of vector-borne pathogens in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:88.

Githaka N, Konnai S, Kariuki E, Kanduma E, Murata S, Ohashi K. Molecular detection and characterization of potentially new Babesia and Theileria species/variants in wild felids from Kenya. Acta Trop. 2012;124:71–8.

Reichard MV, Gray KM, Van den Bussche RA, d’Offay JM, White GL, Simecka CM, et al. Detection and experimental transmission of a novel Babesia isolate in captive olive baboons (Papio cynocephalus anubis). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2011;50:500–6.

Penzhorn BL, Kjemtrup AM, López-Rebollar LM, Conrad PA. Babesia leo nov. sp. from lions in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, and its relation to other small piroplasms. J Parasitol. 2001;87:681–5.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bayer Health Care-Animal Health Division for kindly supporting the publication of this manuscript in the framework of the 10th CVBD World Forum symposium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GB and LS planned and conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. MFC participated in performing the phylogenetic analyses and writing the manuscript. LC participated in conceiving the study and in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Sequences of Theileria annae (synonyms Babesia cf. microti and Babesia microti-like) amplified from foxes and deposited in the GenBank database and/or published in peer-reviewed journals. The table contains information gathered to the author’s best ability.

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Phylogenetic tree of near-complete 18S rRNA and incomplete gene sequences of T. annae, B. microti, and B. microti-related parasites including incomplete sequences isolated from parasites infecting dogs and foxes using maximum likelihood. The sequence of each isolate is labeled with its gene accession number, isolate designation, host, and geographic origin of isolation. The bootstrap values based on 1,000 replicates are displayed next to the branches. The tree is rooted using closely related Babesia parasites infecting rodents and carnivores of Clade I as defined in Schnittger et al. [3]. Wherever applicable, the number of pooled sequences is given. Accession number of pooled sequences are Babesia rodhaini: M87565, DQ641423, AB049999; Babesia sp. leopard [50]: JQ861967, JQ861965, JQ861972; Babesia leo [52]: AY452708, AF244911; Babesia felis: AY452698, AY452699, AY452700, AY452700, AY452701, AY452702, AY452703, AY452704, AY452705, AY452706, AY452707. Babesia sp. baboon: GQ225744 [51] and Babesia sp. Caracal AF244913, AF244914 [52]. Clades marked by brackets display a highly significant bootstrap value (≥85). The evolutionary distance is shown in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 92 nucleotide sequences from which all positions with less than 80% site coverage were eliminated resulting in a total of 1281 positions in the final dataset. After estimation of the shape parameter [31], the T92 + G + I model was applied to infer the tree using the MEGA6 software [32].

Additional file 3: Figure S2.

Phylogenetic tree of tubulin beta gene sequences of T. annae, B. microti and B. microti-related parasites using maximum likelihood. The sequence of each isolate is labeled with its gene accession number, isolate designation, host, and geographic origin of isolation. The bootstrap values based on 1,000 replicates are displayed next to the branches. The tree is rooted using Theileria and Babesia parasites of Clade V and VI as defined in Schnittger et al. [3], respectively. Clades marked by brackets display a highly significant bootstrap value (≥85). The evolutionary distance is shown in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 32 nucleotide sequences of which all positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated resulting in a total of 879 positions in the final dataset. After estimation of the shape parameter [34], the T92 + G + I model was applied to infer the tree using the MEGA6 software [35].

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Baneth, G., Florin-Christensen, M., Cardoso, L. et al. Reclassification of Theileria annae as Babesia vulpes sp. nov.. Parasites Vectors 8, 207 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0830-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0830-5