Abstract

Background

Piroplasmosis are among the most relevant diseases of domestic animals. Babesia is emerging as cause of tick-borne zoonosis worldwide and free-living animals are reservoir hosts of several zoonotic Babesia species. We investigated the epidemiology of Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. in wild ungulates and carnivores from Northern Italy to determine which of these apicomplexan species circulate in wildlife and their prevalence of infection.

Methods

PCR amplification of the V4 hyper-variable region of the 18S rDNA of Babesia sp./Theileria sp was carried out on spleen samples of 1036 wild animals: Roe deer Capreolus capreolus (n = 462), Red deer Cervus elaphus (n = 52), Alpine Chamois Rupicapra rupicapra (n = 36), Fallow deer Dama dama (n = 17), Wild boar Sus scrofa (n = 257), Red fox Vulpes vulpes (n = 205) and Wolf Canis lupus (n = 7). Selected positive samples were sequenced to determine the species of amplified Babesia/Theileria DNA.

Results

Babesia/Theileria DNA was found with a mean prevalence of 9.94% (IC95% 8.27-11.91). The only piroplasms found in carnivores was Theileria annae, which was detected in two foxes (0.98%; IC95% 0.27-3.49). Red deer showed the highest prevalence of infection (44.23%; IC95% 31.6-57.66), followed by Alpine chamois (22.22%; IC95% 11.71-38.08), Roe deer (12.55%; IC95% 9.84-15.89), and Wild boar (4.67%; IC95% 2.69-7.98). Genetic analysis identified Babesia capreoli as the most prevalent piroplasmid found in Alpine chamois, Roe deer and Red deer, followed by Babesia bigemina (found in Roe deer, Red deer and Wild boar), and the zoonotic Babesia venatorum (formerly Babesia sp. EU1) isolated from 2 Roe deer. Piroplasmids of the genus Theileria were identified in Wild boar and Red deer.

Conclusions

The present study offers novel insights into the role of wildlife in Babesia/Theileria epidemiology, as well as relevant information on genetic variability of piroplasmids infecting wild ungulates and carnivores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. are protozoan parasites transmitted mainly by ticks and able to infect erythrocytes and/or leukocytes of a wide variety of domestic and wild animals [1] and Babesia is the second most common parasite found in the blood of mammals after trypanosomes [2]. Some species of the genus Theileria such as T. annulata and T. parva are highly pathogenic to cattle and cause significant mortality among susceptible animals [3, 4]. Other Theileria spp. are considered to be benign or less pathogenic probably because of a long evolutionary relationship between the parasite and the host. Nevertheless, clinical disease may occur in stressful situations related to translocation of wildlife or/and when the host is debilitated by other parasitic organisms or malnutrition [5–7]. Although piroplasmosis is among the most relevant diseases of domestic animals [8, 9], many unknowns remain concerning their epidemiology and life cycle in the Ixodid tick vector as well as in the vertebrate host, especially for factors involved in the role of wildlife as reservoirs of infection [2, 10]. Recently, white-tailed deer were indicated as being responsible for reintroducing the tick vector of Cattle Tick Fever in Central Texas and hence the piroplasms responsible for bovine babesiosis (Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina) [11]. Different Theileria and Babesia species were reported in wildlife with high prevalence of infection [5, 9, 12], some of which are recognized zoonotic pathogens, such as Babesia divergens[13], Babesia divergens-like [14, 15], Babesia venatorum (formerly Babesia sp. EU1) [16–18], Babesia microti[2, 19, 20] and B. microti-like [21, 22]. No Theileria species have to date been identified as causative agents of zoonotic infections [2]. The epidemiology of Babesia and Theileria in European wildlife is complex. Besides the variety of host species susceptible to infection (i.e. cervids: Roe deer Capreolus capreolus, Red deer Cervus elaphus, Fallow deer Dama dama; bovids: Alpine Chamois Rupicapra rupicapra, Spanish Ibex Capra pyrenaica; suids: wild boar Sus scrofa) [5, 23–25], different tick vectors contribute to piroplasmid transmission: Ixodes ricinus is the most common vector of Babesia species in Europe but recently, 5 species of ticks were found to be infected with piroplasmids in Central and Northern Italy [26], suggesting the need to investigate other potential vector species since novel tick/pathogen associations were detected in Hyalomma marginatum, Rhipicephalus sanguineus and I. ricinus[26]. In North America, I. scapularis is the primary vector responsible for transmission of B. microti to humans [2]. As for Babesia, the occurrence of Theileria depends on the simultaneous presence of appropriate vector ticks and host species. In the USA, the lone-star tick Ambloymma americanum is the only known vector of T. cervi, which mainly infects wild ruminants, particularly White-tailed deer [27, 28]. In Europe, little is known about tick species involved in the transmission of Theileria to cervids, and it is assumed that ticks of the genera Ixodes, Hyalomma and Rhiphicephalus might be involved [5, 7]. As biomolecular tools are easily available, in recent years many studies have investigated the epizootiology of piroplasmids circulating in wildlife, leading to the identification of several Babesia and Theileria species strictly related to wild animals or of strains shared with domestic animals [11, 29]. The novel B. venatorum is strictly related to Roe deer presence [24], while B. capreoli was detected in Red deer from Ireland, where Roe deer are absent [24]. C. capreolus was also identified as a possible source of fatal babesial infection for the Alpine chamois [30, 31]. The territorial expansion and population increase that involved Roe deer in several European countries including Italy [32], led to increased contacts and spatial overlap with R. rupicapra populations and hence to an increased possibility of infection of this species with piroplasms of cervids such as B. capreoli[23]. The zoonotic B. divergens is also reported to infect European wild ungulates and has probably one of the largest host ranges described to date for a Babesia species [33], although Malandrin et al. [13] recently reviewed previous identifications of this parasite attributing many of them to B. capreoli. In contrast to ungulates, information on the occurrence and prevalence of piroplasmids in wild canids is limited [34]. In Europe, a continent where the Red fox is present at high densities [35], B. microti-like piroplasms were molecularly confirmed in foxes from Central and Northern Spain [9, 36, 37], Croatia [38] and Portugal [34]. In Portugal, a single fox was also found infected with B. canis[34]. Considering the relevant insights into piroplasm-wildlife epidemiology [39, 40], the increasing importance of Babesia as an emerging zoonotic disease [2, 10] and the lack of information on piroplasm epidemiology in Northwestern Italy [23], we widely investigated Babesia/Theileria infection prevalence in wild ungulates and carnivores from the Piedmont region (Italy) and their biomolecular characteristics, by amplifying and sequencing part of the V4 hyper-variable region of the 18S rRNA gene.

Methods

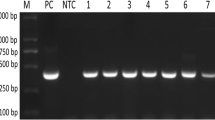

A total of 1036 free-ranging wild ungulates and carnivores were sampled during a period of 5 years (from 2008 to 2012), in a wide area of Northern Italy (2 million hectares), that includes a wide range of habitats and different ecological niches ranging from low altitude intensively cultivated farm land to Alpine forests and meadows. The animals included in the study were either culled by hunters, accidentally found dead, or culled within official programs for species demographic control. Ethical and institutional approval was given by the Department of Veterinary Sciences, University of Turin (Italy). Six species of ungulates were sampled: Roe deer Capreolus capreolus (n = 462), Red deer Cervus elaphus (n = 52), Alpine chamois Rupicapra rupicapra (n = 36), Fallow deer Dama dama (n = 17) and Wild boar Sus scrofa (n = 257). Two carnivore species, Red fox Vulpes vulpes (n = 205) and Wolf Canis lupus (n = 7) were also included in the study. All animals were promptly brought to the Turin Veterinary Faculty for necropsy where a portion of splenic tissue was collected from each animal and stored at -20°C until further processing. All standard precautions were taken to minimize the risk of cross-contamination (preparation of PCR and addition of DNA was carried out in separate laminar-flow cabinets using DNA-free disposable material. Positive and negative control samples were processed in parallel with all samples). Total genomic DNA was extracted from ≈ 10 mg of spleen using the commercial kit GenElute® Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Direct molecular detection of Babesia spp./Theileria spp. DNA was carried out using a semi-nested PCR protocol targeting the V4 hyper-variable region of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene. The primers used are highly conserved and can amplify a wide variety of Babesia and Theileria species [41, 42]. The first amplification was carried out using the primers RLB-F2 (5’-GACACAGGGAGGTAGTGACAAG-3’) and RLB-R2 (5’-CTAAGAATTTCACCTCTGACAGT-3’) [41]. The PCR reaction was carried out in a final volume of 25 μl, using Promega PCR Master Mix (Promega Corporation, WI, USA), 20pM of each primer, and ≈ 100 ng of DNA template. The amplification included a 5 min denaturation step at 95°C followed by 25 repeats of 30 s at 95°C, 45 s at 50°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplicons (1 μl) of the first PCR step were used as template for the second amplification which used RLB-FINT (5’-GACAAGAAATAACAATACRGGGC-3’) [43] as internal forward primer, together with RLB-R2. The reaction mixture and cycling program were identical to the direct RLB-F2/RLB-R2 amplification, but the cycle number was increased to 40, whereas the annealing temperature was 50°C in the first PCR and 55°C in the second PCR. A positive and a negative control sample were included in each amplification reaction. Amplicons were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%) and visualized by staining with Gel Red Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (VWR International Milano, Italy). Selected positive amplicons were purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit, QIAGEN) and both DNA strands were directly sequenced (Macrogen; http://www.macrogen.com). The resulting sequences were compared with the NCBI/Genbank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), and ClustalX software (http://www-igbmc.u-strasbg.fr/BioInfo) was used to construct multiple-sequence alignments. All statistical analysis was carried out using R software 3.0.1 (R Core Team 2012). Chi-square test was used to assess potential differences in Babesia/Theileria infection rate between groups (animals were grouped by species, age, sex, and year of sampling).

Results

Prevalence of Babesia/Theileria spp. DNA in wildlife

Piroplasm DNA was detected with an overall prevalence of 9.94% (IC95% 8.27-11.91). Detailed prevalence data for each species are reported in Table 1. Herbivores (P = 15.7%; IC95% 12.93-18.92) were significantly more infected (χ2 = 32.55, p < 0.0000; OR = 19.55, 4.77-80.14) than carnivores (P = 0.94%; IC95% 0.26-3.37) as Babesia/Theileria DNA was amplified from two foxes, while all the results from the wolves examined were negative by PCR. Among herbivores, the highest prevalence of infection was reported in Red deer (P = 44.23%; IC95% 31.6-57.66). This species was significantly more infected than the other examined ungulates (χ2 = 51.06, p < 0.0000; OR = 6.88, 3.8-12.48). On the other hand, Wild boar results showed significantly less infection than herbivore species (χ2 = 20.00, p < 0.0000; OR = 0.2631, 0.14-0.49). Sex and age did not significantly influence the infection status of any of the species tested (data not shown), nor any statistically significant difference between sampling years was recorded (data not shown).

Sequencing and molecular classification

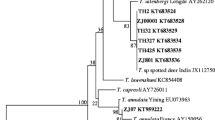

A total of 28 positive samples were sequenced and deposited in GenBank under accession numbers from KF773715 to KF773741 (Table 2). B. capreoli was the most prevalent species (P = 46.43%; CI95% 29.53-64.19), it was found in Alpine chamois (n = 4), Roe deer (n = 4), and Red deer (n = 5). All four B. capreoli isolates from Alpine chamois [GenBank: from KF773728 to KF773730] showed 100% identity with the B. capreoli described by Hoby et al., [30] in fatal cases of babesiosis in chamois from Switzerland [GenBank:EF545558 to EF545562], while a Red deer isolate [Genbank: KF773718] showed 100% homology with B. capreoli [GenBank: FJ944827- FJ944828] identified in Roe deer in France [13]. B. bigemina was the second most prevalent Babesia species. It was identified in Roe deer (n = 4), Red deer (n = 1) and Wild boar (n = 2). All isolates showed 99% identity with B. bigemina [Genbank: HQ264116], infecting White-tailed deer in Southern Texas [11]. Roe deer (n = 2) were also infected with the zoonotic B. venatorum. Both isolates showed 100% identity with the B. venatorum [GenBank: AY046575] described in two human cases in Italy and Austria [16]. Piroplasms of the genus Theileria were detected in Wild boar (n = 2) and Red deer (n = 2). Wild boar isolates showed 100% identity with Theileria sp. CS-2012 [Genbank: JQ751279] described in Wild boars and Sambar deer in Thailand. An isolate from Red deer [Genbank: KF773724] showed 100% identity with Theileria sp. 3185/02 described in a Red deer imported from Germany to Spain [Genbank: AY421708] [7], while another Red deer isolate [GenBank: KF773725] showed 100% identity with Theileria sp. OT3 described in chamois, deer and sheep from Spain [GenBank: DQ866840] [44, 45]. T. annae (syn. B. microti-like) was detected in the two PCR positive foxes. One isolate [GenBank: KF773740] showed 100% identity with T. annae amplified from Croatian foxes [GenBank: HM212628] [38], while the second isolate [Genbank: KF773741], although very similar, has CT instead of AA at 268–269 pb. The phylogenetic relationships among the sequenced samples are reported in Figure 1.

Discussion

Piroplasmids are frequently found to infect free-living animals worldwide and are gaining increasing attention as emerging tick-borne zoonosis [16, 46, 47]. Increased wildlife-human interactions due to socio-economic changes have enhanced the risk of contracting zoonotic diseases [23]. This is especially true for vector-borne pathogens where the presence of the vector in the area has increased thanks to climatic changes and/or changes in the environment or in host species presence [48–50]. Babesia and Theileria are traditionally known for their relevant economic impact on the livestock industry and on human health. Several wild animals are known to be reservoirs of zoonotic Babesia species [2]. Although piroplasmosis in wildlife is mostly asymptomatic [46] recent cases of fatal babesiosis were recorded in Alpine chamois infected with B. capreoli[30, 31]. Malandrin et al., [13] clarified the ambiguous classification of B. divergens-like parasites isolated from cervids, revealing that most infections reported from wildlife can likely be ascribed to B. capreoli. Amplification and sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene was essential to correctly identify the two species (B. divergens and B. capreoli) as distinct. PCR protocols targeting the V4 hyper-variable region of 18S rDNA, like the one used in the present study, are able to identify a wide variety of Babesia/Theileria species and may also detect less closely related genotypes, such as the B. microti complex or species related to B. odocoilei[29]. In our study no B. divergens was identified in any of the sequenced samples, while the closely related B. capreoli was the most prevalent species, confirming that where Roe deer are abundant, B. capreoli is also widely present. B. venatorum was first identified in splenectomized human patients in Italy and Austria [16] and in Roe deer from Eastern Italy [23, 51], but to our knowledge this is the first report of B. venatorum from the Western Alps. The high homology found between the 18S rDNA sequences of B. venatorum deposited in Genbank suggests that the parasite widely circulates among wild ungulates across Europe. Over the past 30 years, reintroduction of both Red deer and Roe deer occurred for restocking purposes from Central Europe and from the Balkans to the studied area [52] and the founding effect of animal translocation could also be implied for the high homology of B. venatorum found across the Alps. In consideration of B. bigemina, in the current study, it was detected in Roe deer, Red deer and Wild boar. Even if B. bovis and B. bigemina infection have been already reported in White-tailed deer from North America [11], to our knowledge this is the first report of B. bigemina infecting wild ungulates in Europe, suggesting the existence of a common epidemiological cycle among wildlife and sympatric livestock, since cattle are the recognized reservoir of this parasite [11, 53]. The prevalence of infection recorded in our study differs greatly between the species considered. Red deer showed the highest prevalence of infection with 44% of sampled Red deer positive by PCR. Prevalences reported for the same species in Italy (12.5%) [23] as well as in other countries are significantly lower (in Ireland 26%) [24], in USA 12% [11]. Many Red deer populations present in Piedmont are characterized by high densities of animals [54]. In particular, 62.5% of Babesia-infected Red deer came from a low altitude fenced forest (Parco Regionale La Mandria; 3600 ha) mainly composed of broad-leaved trees and permanent meadows where the estimated Red deer population is very high (6–14 heads/km2) [55]. Tick-favorable conditions together with the high density population and gregarious habits of C. elaphus are possible causes of the high infection rate we found in Red deer. The Roe deer, even if less gregarious and territorial [56], is the second most infected species in Piedmont, confirming the high susceptibility of C. capreolus to piroplasmid infection. The prevalence of Babesia/Theileria DNA we found in Piedmont (12.55%) falls within the range reported for the species in Italy and in other European countries [17, 23, 29]. Our data also confirmed the low susceptibility of wild boar which were found infected at low prevalence (P = 4.67%), as reported also from Eastern Italy (2.6%) [23]. T. annae is the only piroplasmid we detected in Red foxes. Natural infection of V. vulpes with T. annae had already been documented with the prevalence of infection being higher than recorded in the Western Alps, in several European countries including Italy (50% [1/2]) [23], Northern Spain (20% [1/5]) [37], Portugal (69.2% [63/91] [34] and Croatia (5.2% [10/191]) [38].

Conclusions

The role of wildlife as reservoirs of zoonotic Babesia species, as well as the involvement of free-ranging ungulates in the epidemiology of piroplasmids of veterinary importance is well established [2, 39, 57]. Nevertheless, many gaps in host-piroplasmid and host-tick interactions remain. For many of the numerous Babesia/Theileria species, some relevant biological aspects (e.g. reservoir hosts(s), and vectors(s)) as well as molecular characteristics remain poorly investigated. Yabsley et al., [2] reported how PCR-based studies with sequence analysis of piroplasms circulating in wildlife are needed to identify the causative agents of novel cases of human babesiosis as well as for managing effective surveillance plans on potential reservoirs and vectors. The data presented in this study give valuable insights on the piroplasms circulating in free-ranging ungulates and carnivores in an extensive area where wildlife lives in sympatry with a high-density human and livestock population.

References

Duh D, Punda-Polić V, Trilar T, Avšič-Županc T: Molecular detection of Theileria sp. in ticks and naturally infected sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2008, 151 (2–4): 327-331.

Yabsley MJ, Shock BC: Natural history of Zoonotic Babesia: role of wildlife reservoirs. Int J Parasitol. 2013, 2: 18-31.

Tait A, Hall FR: Theileria annulata: control measures, diagnosis and the potential use of subunit vaccines. Rev Sci Tech. 1990, 9 (2): 387-403.

Gitau GK, Perry BD, McDermott JJ: The incidence, calf morbidity and mortality due to Theileria parva infections in smallholder dairy farms in Murang’a District, Kenya. Prev Vet Med. 1999, 39 (1): 65-79. 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00137-8.

Sawczuk M, Maciejewska A, Skotarczak B: Identification and molecular characterization of Theileria sp. infecting red deer (Cervus elaphus) in northwestern Poland. Eur J Wildl Res. 2008, 54: 225-230. 10.1007/s10344-007-0133-z.

Kocan AA, Kocan KM: Tick-transmitted protozoan diseases of wildlife in North America. Bull Soc Vector Ecol. 1991, 16: 94-108.

Höfle U, Vicente J, Nagore D, Hurtado A, Pena A, de la Fuente J, Gortazar C: The risks of translocating wildlife. Pathogenic infection with Theileria sp. and elaeophora elaphi in an imported red deer. Vet Parasitol. 2004, 126: 387-395.

Schnittger L, Yin H, Gubbels MJ, Beyen D, Niemann S, Jorgejan F, Ahmed JS: Phylogeny of sheep and goat Theileria and Babesia parasites. Parasitol Res. 2003, 91: 938-406.

Criado-Fornelio A, Martinez-Marcos A, Buling-Sarana A, Barba-Carretero JC: Molecular studies on Babesia, Theileria and Hepatozoon in southern Europe. Part I. Epizootiological aspects. Vet Parasitol. 2003, 113: 189-201. 10.1016/S0304-4017(03)00078-5.

Schnittger L, Rodriguez AE, Florin-Christensen M, Morrison DA: Babesia: a world emerging. Inf Gen Evol. 2012, 12: 1788-1809. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.07.004.

Holman PJ, Carroll JE, Pugh R, Davis DS: Molecular detection of Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianuns) from Tom Green County in Central Texas. Vet Par. 2011, 117: 298-304.

Galuppi R, Aureli S, Bonoli C, Caffara M, Tampieri MP: Detection and molecular characterization of Theileria sp. in fallow deer (Dama dama) and ticks from an Italian natural preserve. Res Vet Sci. 2011, 91: 110-115. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.029.

Malandrin L, Jouglin M, Sun Y, Brisseau N, Chauvin A: Redescription of Babesia capreoli (Enigk and Friedhoff, 1962) from roe deer (Capreolus capreolus): isolation, cultivation, host specificity, molecular characterization and differentiation from Babesia divergens. Int J Parasitol. 2010, 40: 277-284. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.08.008.

Olmeda AS, Armstrong PM, Rosenthal BM, Valladares B, Del Castillo A, De Armas F, Miguelez M, González A, Rodríguez Rodríguez JA, Spielman A, Telford SR: A subtropical case of human babesiosis. Acta Trop. 1997, 67: 229-234. 10.1016/S0001-706X(97)00045-4.

Qi C, Zhou D, Liu J, Cheng Z, Zhang L, Wang L, Wang Z, Yang D, Wang S, Chai T: Detection of Babesia divergens using molecular methods in anemic patients in Shandong Province, China. Parasitol Res. 2011, 109: 241-245. 10.1007/s00436-011-2382-8.

Herwaldt BL, Cacciò S, Gherlinzoni F, Aspöck H, Slemenda SB, Piccaluga P, Martinelli G, Edelhofer R, Hollenstein U, Poletti G, Pampiglione S, Löschenberger K, Tura S, Pieniazek NJ: Molecular characterization of a non-Babesia divergens organism causing zoonotic babesiosis in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003, 9 (8): 942-948. 10.3201/eid0908.020748.

Duh D, Petrovec M, Bidovec A, Avis-Zupanc T: Cervids as Babesiae hosts, Slovenia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005, 11 (7): 1121-1123. 10.3201/eid1107.040724.

Bonnet S, Jouglin M, L’Hostis M, Chauvin A: Babesia sp. EU1 from roe deer and transmission within Ixodes ricinus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007, 13 (8): 1208-1210. 10.3201/eid1308.061560.

Anderson JF, Mintz ED, Gadbaw JJ, Magnarelli LA: Babesia microti, human babesiosis, and Borrelia bugdorferi in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1991, 29: 2779-2783.

Telford SR, Spielman A: Reservoir competence of white-footed mice for Babesia microti. J Med Entomol. 1993, 30: 223-227.

Matsui T, Inoue R, Kajimoto K, Tamekane A, Okamura A, Katayama Y, Shimoyama M, Chihara K, Saito-ito A, Tsuji M: First documentation of transfusion-associated babesiosis in Japan. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2000, 41: 628-634.

Wei Q, Tsuji M, Zamoto A, Kohsaki M, Matsui T, Shiota T, Telford SR, Ishiara C: Human babesiosis in Japan: isolation of Babesia microti-like parasites from an asymptomatic transfusion donor and from a rodent from an area where babesiosis is endemic. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 2178-2183. 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2178-2183.2001.

Tampieri MP, Galuppi R, Bonoli C, Cancrini G, Moretti A, Pietrobelli M: Wild ungulates as Babesia hosts in northern and central Italy. Vector-Borne Zoonot. 2008, 8 (5): 667-674. 10.1089/vbz.2008.0001.

Zintl A, Finnerty EJ, Murphy TM, de Waal T, Gray JS: Babesias of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland. Vet Res. 2011, 42: 7. 10.1186/1297-9716-42-7.

Ferrer D, Castellà J, Gutierrez JF, Lavin S, Ignasi M: Seroprevalence of Babesia ovis in Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica) in Catalonia, Northeastern Spain. Vet Parasitol. 1998, 75 (2–3): 93-98.

Iori A, Gabrielli S, Calderini P, Moretti A, Pietrobelli M, Tampieri MP, Galuppi R, Cancrini G: Tick reservoirs for Piroplasms in central and northern Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2010, 170: 291-296. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.02.027.

Laird JS, Kocan AA, Kocan KM, Presley SM, Hair JA: Susceptibility of Amblyomma americanum to natural and experimental infections with Theileria cervi. J Wildl Dis. 1988, 24 (4): 679-683. 10.7589/0090-3558-24.4.679.

Chae JS, Waghela SD, Craig TM, Kocan AA, Wagner GG, Holman PJ: Two Theileria cervi SSU RRNA gene sequence types found in isolates from white-tailed deer and elk in North America. J Wildl Dis. 1999, 35 (3): 458-465. 10.7589/0090-3558-35.3.458.

Bastian S, Jouglin M, Brisseau N, Malandrin L, Klegou G, L’Hostis M, Chauvin A: Antibody prevalence and molecular identification of Babesia spp. in Roe deer in France. J Wildl Dis. 2012, 48 (2): 416-424. 10.7589/0090-3558-48.2.416.

Hoby S, Robert N, Mathis A, Schmid N, Meli ML, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Lutz H, Deplazes P, Ryser-Degiorgis MP: Babesiosis in free-living chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) from Switzerland. Vet Par. 2007, 148: 341-345. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.06.035.

Hoby S, Mathis A, Doherr MG, Robert N, Ryser-Degiorgis MP: Babesia capreoli infections in Alpine chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus) from Switzerland. J Wildlife Dis. 2009, 45 (3): 748-753. 10.7589/0090-3558-45.3.748.

Focardi S, Pelliccioni E, Petrucco R, Toso S: Spatial patterns and density dependence in the dynamics of a roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) population in central Italy. Oecologia. 2002, 130 (3): 411-419. 10.1007/s00442-001-0825-0.

Zintl A, Mulcahy G, Skerrett HE, Taylor SM, Gray JS: Babesia divergens, a bovine blood parasite of veterinary and zoonotic importance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003, 16: 622-636. 10.1128/CMR.16.4.622-636.2003.

Cardoso L, Cortes HCE, Reis A, Rodrigues P, Simões M, Lopes AP, Vila-Viçosa MJ, Talmi-Frank D, Eyal O, Solano-Gallego L, Baneth G: Prevalence of Babesia microti-like infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Portugal. Vet Parasitol. 2013, 196 (1–2): 90-95.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.http://www.iucnredlist.org/,

Criado-Fornelio A, Rey-Valeiron C, Buling A, Barba-Carretero JC, Jefferies R, Irwin P: New advances in molecular epizootiology of canine hematic protozoa from Venezuela, Thailand and Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2007, 144: 261-269. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.09.042.

Gimenez C, Casado N, Criado-Fornelio A, de Miguel FA, Dominguez-Penafiel G: A molecular survey of Piroplasmida and Hepatozoon isolated from domestic and wild animals in Burgos (Northern Spain). Vet Parasitol. 2009, 26: 147-150.

Dezdek D, Vojta L, Curkovic S, Lipej Z, Mihaljevic Z, Cvetnic Z, Beck R: Molecular detection of Theileria annae and Hepatozoon canis in foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Croatia. Vet Parasitol. 2010, 172: 333-336. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.05.022.

Penzhorn BL: Babesiosis of wild carnivores and ungulates. Vet Parasitol. 2006, 138: 11-21. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.036.

Hunfeld KP, Hildebrandt A, Gray JS: Babesiosis: Recent insights into an ancient disease. Int J Parasitol. 2008, 38: 1219-1237. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.03.001.

Gubbels JM, de Vos AP, van der Weide M, Viseras J, Schouls LM, de Vries E, Jongejan F: Simultaneous detection of bovine Theileria and Babesia species by reverse line blot hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1999, 37 (6): 1782-1789.

Centeno-Lima S, Do Rosário V, Parreira R, Maia AJ, Freudenthal AM, Nijhof AM, Jongejan F: A fatal case of human babesiosis in Portugal: molecular and phylogenetic analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8 (8): 760-764. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01074.x.

Schnittger L, Yin H, Qi B, Gubbels MJ, Beyer D, Niemann S, Jongejan F, Ahmed JS: Simultaneous detection and differentiation of Theileria and Babesia parasites infecting small ruminants by reverse line blotting. Parasitol Res. 2004, 92 (3): 189-196. 10.1007/s00436-003-0980-9.

García-Sanmartín J, Aurtenetxe O, Barral M, Marco I, Lavin S, García-Pérez AL, Hurtado A: Molecular detection and characterization of piroplasms infecting cervids and chamois in Northern Spain. Parasitol. 2007, 134: 391-398. 10.1017/S0031182006001569.

Nagore D, García-Sanmartín J, García-Pérez AL, Juste RA, Hurtado A: Identification, genetic diversity and prevalence of Theileria and Babesia species in a sheep population from Northern Spain. Int J Parasitol. 2004, 34 (9): 1059-1067. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.05.008.

Homer MJ, Aguilar-Delfin I, Telford SRI, Krause PJ, Persing DH: Babesiosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000, 13 (3): 451-469. 10.1128/CMR.13.3.451-469.2000.

Schorn S, Pfister K, Reulen H, Mahling M, Silagh C: Occurrence of Babesia spp., Rickettsia spp. and Bartonella spp. in Ixodes ricinus in Bavarian public parks, Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4: 135. 10.1186/1756-3305-4-135.

Semenza JC, Menne B: Climate change and infectious diseases in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009, 9: 365-375. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70104-5.

Gortazar C, Ferroglio E, Hofle U, Frolich K, Vicente J: Diseases shared between wildlife and livestock: a European perspective. Eur J Wildl Res. 2007, 53: 241-256. 10.1007/s10344-007-0098-y.

Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD: Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife: threats to biodiversity and human health. Science. 2000, 287 (5452): 443-449. 10.1126/science.287.5452.443.

Cassini R, Bonoli C, Montarsi F, Tessarin C, Marcer F, Galuppi R: Detection of Babesia EU1 in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Northern Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2010, 171 (1–2): 151-154.

Randi E: Management of wild ungulate populations in Italy: captive-breeding, hybridisation and genetic consequences of translocations. Vet Res Comm. 2005, 29 (Suppl 2): 71-75.

Cantu AC, Ortega AS, Garcia-Vasquez Z, Mosqueda J, Henke SE, George JE: Epizootiology of Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina in free-ranging white-tailed deer in northeastern Mexico. J Parasitol. 2009, 95: 536-542. 10.1645/GE-1648.1.

Mattioli S, Meneguz PG, Brugnoli A, Nicoloso S: Red deer in Italy: recent changes in range and numbers. Hystrix It J Mamm. 2001, 2 (1): 27-35.

Bergagna S, Zoppi S, Ferroglio E, Gobetto M, Dondo A, Di Giannatale E, Gennero MS, Grattarola C: Epidemiologic Survey for Brucella suis Biovar 2 in a Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) Population in Northwest Italy. J Wildl Dis. 2009, 45 (4): 1178-1181. 10.7589/0090-3558-45.4.1178.

Pandini W, Cesaris C: Homerange and habitat use of roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) reared in captivity and released in the wild. Hystrix It J Mamm. 1997, 9 (1–2): 45-50.

de León AA P, Strickman DA, Knowles DP, Fish D, Thacker E, de la Fuente J, Krause PJ, Wikel SK, Miller RS, Wagner GG, Almazán C, Hillman R, Messenger MT, Ugstad PO, Duhaime RA, Teel PD, Ortega-Santos A, Hewitt DG, Bowers EJ, Bent SJ, Cochran MH, McElwain TF, Scoles GA, Suarez CE, Davey R, Howell Freeman JM, Lohmeyer K, Li AY, Guerrero FD, Kammlah DM, Phillips P, Pound JM, Group for Emerging Babesioses and One Health Research and Development in the U.S: One Health approach to identify research needs in bovine and human babesioses: workshop report. Parasit Vectors. 2010, 3 (1): 36. 10.1186/1756-3305-3-36.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by funds from the Piedmont Regional Administration (“Convenzione tra la Regione Piemonte e la Facoltà di Medicina Veterinaria dell’Università degli Studi di Torino per la razionalizzazione ed integrazione delle attività di raccolta e smaltimento degli animali selvatici morti o oggetto di interventi di contenimento”). The authors would like to acknowledge the precious help of Drs. Davide Grande, Angelo Romano and Giulio Falzoni for the support given to the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SZ carried out the molecular studies with EB, participated in the sequence analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; AT participated and supervised the laboratory work, MGC directly provided many of the tested chamois samples and organized sample collection in the field, IGFDM and CG collaborated to PCR setup and sample sequencing, EF coordinated the investigation, and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanet, S., Trisciuoglio, A., Bottero, E. et al. Piroplasmosis in wildlife: Babesia and Theileria affecting free-ranging ungulates and carnivores in the Italian Alps. Parasites Vectors 7, 70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-70