Abstract

Background

Engineered strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae have significantly improved the prospects of biorefinery by improving the bioconversion yields in lignocellulosic bioethanol production and expanding the product profiles to include advanced biofuels and chemicals. However, the lignocellulosic biorefinery concept has not been fully applied using engineered strains in which either xylose utilization or advanced biofuel/chemical production pathways have been upgraded separately. Specifically, high-performance xylose-fermenting strains have rarely been employed as advanced biofuel and chemical production platforms and require further engineering to expand their product profiles.

Results

In this study, we refactored a high-performance xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae that could potentially serve as a platform strain for advanced biofuels and biochemical production. Through combinatorial CRISPR–Cas9-mediated rational and evolutionary engineering, we obtained a newly refactored isomerase-based xylose-fermenting strain, XUSE, that demonstrated efficient conversion of xylose into ethanol with a high yield of 0.43 g/g. In addition, XUSE exhibited the simultaneous fermentation of glucose and xylose with negligible glucose inhibition, indicating the potential of this isomerase-based xylose-utilizing strain for lignocellulosic biorefinery. The genomic and transcriptomic analysis of XUSE revealed beneficial mutations and changes in gene expression that are responsible for the enhanced xylose fermentation performance of XUSE.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a high-performance xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain, XUSE, with high ethanol yield and negligible glucose inhibition. Understanding the genomic and transcriptomic characteristics of XUSE revealed isomerase-based engineering strategies for improved xylose fermentation in S. cerevisiae. With high xylose fermentation performance and room for further engineering, XUSE could serve as a promising platform strain for lignocellulosic biorefinery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The development of xylose-utilizing strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae has improved the prospects of lignocellulosic biorefinery, enabling the creation of full-scale second-generation bioethanol production plants worldwide [1]. However, the main product of xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strains is generally limited to bioethanol, and further strain engineering is required to expand the product profiles of lignocellulosic biorefinery to include advanced biofuels and chemicals [2]. The primary advantage of using xylose-fermenting strains in lignocellulosic biorefinery is the improvement in the overall bioconversion efficiency [3]. In addition, the unique metabolic characteristics during xylose fermentation, different from those of glucose fermentation, could also place xylose-fermenting strains in a more favorable position for the shift in products from ethanol to advanced biofuels and chemicals. Specifically, the limited accessibility of acetyl-CoA, a central branch point in biosynthetic pathways for advanced biofuels and chemicals, could be resolved in xylose-fermenting strains [2]. Among the engineered strains of S. cerevisiae, strains harboring a redox-neutral xylose isomerase-based pathway seem to have a particular advantage over oxidoreductase-based strains, since they introduce no burden in terms of intensive cofactor requirements in the biosynthetic pathways for advanced biofuels and chemicals [4, 5]. Expanding the product profiles of xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae, however, has not been fully explored until recently, since strain engineering has mainly focused on the improvement of xylose fermentation and glucose/xylose cofermentation efficiency [6]. Only a few xylose-fermenting strains have been reported to produce advanced biofuels and chemicals, such as 1-hexadecanol, lactic acid, 2,3-butanediol, and isobutanol, with limited success obtained by introducing the respective synthetic pathways into ordinary xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strains [7,8,9,10,11]. With recent strain engineering efforts, the xylose fermentation and glucose/xylose cofermentation performance of engineered strains have been greatly improved [6]. However, these high-performance strains, generally developed through plasmid-based integration using auxotrophic markers followed by evolutionary engineering, have rarely been engineered as hosts for advanced biofuel and chemical production [12,13,14,15]. The recent development of a refactored oxidoreductase pathway-based xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain using the markerless genome-editing tool CRISPR–Cas9 has enabled the development of high-performance xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae producing advanced biofuels and chemicals [16].

In this study, we developed a high-performance xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain as a potential production host for advanced biofuels and biochemicals. The introduction of isomerase-based xylose catabolic pathway genes into the gre3 and pho13 loci using a markerless genome-editing tool, the CRISPR–Cas9 system, and subsequent evolutionary engineering generated a high-performance xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae, XUSE. The xylose fermentation performance of XUSE was comparable to that of SXA-R2P-E, a representative high-performance xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strain reported previously [15], and XUSE exhibited adequate cofermentation of glucose and xylose with negligible glucose inhibition. The genomic and transcriptomic analysis of XUSE revealed isomerase-based pathway-specific engineering strategies that could enable further improvement in xylose fermentation performance in terms of ethanol titer, yield and productivity. Consequently, this study provides a promising platform strain of S. cerevisiae for advanced biofuel and chemical production from lignocellulosic biomass and offers xylose isomerase pathway-specific engineering strategies for maximizing the xylose fermentation performance of S. cerevisiae.

Results and discussion

Development of an efficient xylose-fermenting strain of XUSE

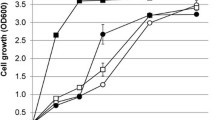

To develop a high-performance xylose-utilizing strain, we sought to refactor one of the best xylose-utilizing strains, SXA-R2P-E [15], using the CRISPR–Cas9 system. To this end, a rationally engineered strain of S. cerevisiae was constructed based on the genetic background of SXA-R2P-E (Δgre3, Δpho13, URA::GPDp-xylA*3-CYC1t-TEFp-XKS1-CYC1t, Leu::GPDp-xylA*3-RPM1t-TEFp-tal1-CYC1t) [15]. Specifically, xylose isomerase mutant (xylA*3) and xylulokinase (XKS1) genes were integrated into the gre3 loci, and then, an additional copy of the xylose isomerase mutant and transaldolase (TAL1) genes was integrated into pho13 loci to simultaneously integrate and delete the chosen target genes. The rationally engineered strain was then further improved by evolutionary engineering, generating an efficient xylose-fermenting strain of S. cerevisiae, XUSE, through combinatorial engineering. XUSE efficiently converted xylose to ethanol, demonstrating comparable xylose fermentation performance to that of SXA-R2P-E (Fig. 1). During 72 h of fermentation, XUSE completely utilized 20 g/L xylose and produced ethanol with a yield of 0.43 g ethanol/g xylose. Interestingly, XUSE generated less cell biomass and produced more ethanol than SXA-R2P-E during low-cell-density fermentation with an initial OD of 0.2, resulting in a slightly higher ethanol yield (0.43 g/g vs 0.4 g/g). This result suggests that the XUSE strain distributes its carbon source more efficiently to ethanol production rather than to cell growth, which would be a beneficial feature in a production host. Similar to SXA-R2P-E, XUSE demonstrated xylose-fermenting performance competitive with that of previously reported strains (Table 1), suggesting successful refactoring to produce a representative xylose-fermenting strain that can be easily engineered for advanced biofuel and biochemical production.

Micro-aerobic fermentation of xylose with XUSE and SXA-R2PE, one of the best xylose-fermenting strains, with an initial OD of a–c 0.2 and d–f 10. a, d Cell growth, b, e xylose utilization, c, f ethanol production. Strain identifications (XUSE: ●, SXA-R2PE: ○) are described in the text. Error bars represents standard deviation of biological triplicates

Evaluation of the glucose/xylose cofermentation performance of XUSE

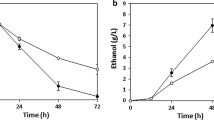

In addition to xylose fermentation performance, the efficient cofermentation of glucose and xylose is also important in developing production hosts for lignocellulosic biorefinery. To evaluate the cofermentation performance of XUSE, we conducted mixed-sugar fermentation of glucose and xylose with varying concentrations of glucose (Fig. 2). When 20 g/L glucose and 20 g/L xylose were supplied, XUSE produced 18.65 g/L ethanol with a yield of 0.46. XUSE exhibited a similar xylose consumption rate during cofermentation to that of SXA-R2P-E (0.2 g/L/h for XUSE vs 0.21 g/L/h for SXA-R2P-E). The total sugar and xylose consumption rates were 0.23 and 0.11 g/L/h, respectively. Interestingly, the xylose consumption rates of XUSE were not significantly affected by the presence of glucose when the glucose concentration was in the range of 0–20 g/L (Fig. 3). Moreover, XUSE simultaneously consumed both xylose and glucose throughout the fermentation process, indicating efficient cofermentation performance (Figs. 2, 3). The xylose consumption rate of XUSE was 0.22, 0.22, and 0.2 g/L/h in the presence of 0, 10, and 20 g/L glucose, respectively. Simultaneous cofermentation has rarely been reported in representative xylose-utilizing S. cerevisiae strains. Most xylose-utilizing strains, especially strains with an oxidoreductase pathway, tend to start utilizing xylose only after the complete utilization of glucose (Table 2). The simultaneous cofermentation of glucose and xylose by XUSE indicates the potential of isomerase-based xylose-utilizing strains for lignocellulosic biorefinery, in which the main challenge in cofermentation would not be simultaneous sugar utilization but further improvement of the xylose fermentation efficiency. Although simultaneous coutilization was still observed, the xylose utilization of XUSE was markedly inhibited when the glucose concentration was greater than 30 g/L, suggesting that glucose inhibition should also be relieved, especially at high glucose concentrations.

Micro-aerobic cofermentation of glucose and xylose with XUSE strain. Cofermentation was conducted with 20 g/L xylose and varying concentration of glucose (a 0 g/L, b 10 g/L, c 20 g/L, d 30 g/L, and e 40 g/L). Ethanol production (○, dash line) and xylose (●, solid line), glucose (

, solid line), and utilization profiles were measured during fermentation. Error bars represents standard deviation of biological triplicates

, solid line), and utilization profiles were measured during fermentation. Error bars represents standard deviation of biological triplicates

Significant nucleotide changes derived from evolutionary engineering improved the xylose fermentation performance of the XUSE strain

To investigate whether beneficial mutations contributed to the improved xylose fermentation performance of XUSE, we conducted whole-genome sequencing analysis and identified two mutations in YGL167C (PMR1G681A) and YMR116C (ASC1Q237*). The mutation and deletion of PMR1, encoding a Golgi Ca2+/Mg2+ ATPase [17], have previously been reported to improve xylose isomerase activity and anaerobic growth on xylose [18, 19]. ASC1, which encodes the G-protein beta subunit and guanine dissociation inhibitor for Gpa2p, has been reported to be involved in the glucose-mediated signaling pathway and invasive growth in response to glucose limitation [20], but little is known about its effect on xylose fermentation. The beneficial effects of the identified mutations on xylose fermentation were then confirmed through complementation experiments (Figs. 4, 5). When the mutated genes were expressed in the respective knockout strains (P11 and P12 strains; Additional file 1: Table S1), xylose consumption and ethanol production were significantly improved, indicating that the evolutionary engineering-derived point mutations in PMR1 and ASC1 contributed to the improved xylose utilization in XUSE. The strains expressing Pmr1G681A and Asc1Q237* consumed 114.8% and 59.6% more xylose and produced 195.9% and 104.4% more ethanol than the strain with the respective wild-type genes (Figs. 4, 5). Interestingly, PMR1 and ASC1 knockout strains exhibited similar fermentation performance to the strains harboring the respective genes with identified mutations, suggesting that the given mutations lead to loss of gene function. A single amino acid change (Pmr1G249V) or the deletion of PMR1 was previously reported to improve xylose utilization in S. cerevisiae [19]. Although the newly identified mutation in PMR1 (Pmr1G681A) is different from the one identified in the previous study, the beneficial impact is still correlative. Although little is known about the effects of the deletion or malfunction of ASC1 on xylose metabolism in S. cerevisiae, inactivation of ASC1 was previously reported to be beneficial for the cell growth of S. cerevisiae under oxygen-depletion conditions [21]. In addition, Asc1p is known as a negative regulator of various metabolic and signal transduction pathways [22] and specifically represses Gcn4p. Gcn4p has been reported to be a representative transcription factor regulating the genes involved in xylose metabolism in efficient xylose-fermenting strains [23]. Therefore, ASC1 malfunction seems to potentially improve cell growth under microaerobic fermentation conditions and enhance the expression of genes involved in xylose metabolism.

The gene expression landscape of XUSE revealed engineering strategies for enhanced xylose metabolism in S. cerevisiae

To understand the mechanisms of the enhanced xylose metabolism of XUSE, the global transcript profiles of XUS (rationally engineered strain) and XUSE (evolved XUS strain) grown on xylose were analyzed. Compared with XUS, XUSE showed a significantly different gene expression landscapes, with 463 upregulated and 675 downregulated genes (> 2-fold). The transcriptional changes in genes involved in the central carbon metabolism are presented on the respective metabolic pathway map (Fig. 6).

Comparison of transcription levels of the genes involved in xylose metabolic pathways and central carbon metabolism of XUSE and XUS strains. The cells were cultured in minimal medium containing 20 g/L xylose under microaerobic conditions and then collected after 20 h of cultivation. The values in the boxes indicate the fold changes of transcription levels in XUSE compared with those in XUS (p < 0.05). The gene names follow those in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD; http://www.yeastgenome.org)

Upon profiling of the differentially expressed genes, we noted a general pattern: the genes involved in the nonoxidative pentose phosphate pathway, such as TKL1, TKL2, and TAL1, were downregulated in XUSE (Fig. 6 and Table 3). This result suggests that evolutionary engineering fine-tuned the xylose metabolic flux by repressing PP pathway enzymes and that the overexpression of PP pathway genes is not a prerequisite for improved xylose fermentation performance in S. cerevisiae. This result partially explains the high performance of the minimally engineered XUSE, in which the PP pathway genes are not overexpressed. Of the PP pathway genes, the TKL2 gene was most strongly downregulated in XUSE, by 3.3-fold (Table 3), and its disruption was previously verified to have a positive effect on xylose fermentation [24].

The genes involved in the regulation of cellular metal ion concentrations, such as PMR1, PHO84, and ISU1, showed significantly changed expression levels in XUSE (Table 3 and Additional file 2: Table S2). The downregulation of PMR1 expression, impeding manganese ion export from the cell through the secretory pathway, corresponds to loss-of-function mutations (Fig. 4). In contrast, PHO84, which encodes an inorganic phosphate transporter with a major role in manganese homeostasis [25], was upregulated by 3.7-fold in XUSE (Additional file 2: Table S2). Therefore, manganese ions accumulated in the cells via this transporter could be more easily incorporated into manganese-requiring enzymes such as xylose isomerase [25]. In addition to manganese ions, the increased cellular iron cation concentration resulting from ISU1 downregulation (0.34-fold, p < 0.05) could also increase xylose isomerase activity and other cellular processes beneficial for xylose metabolism [26]. Although iron cations are not preferred by xylose isomerase, they play essential roles as cofactors for several cellular processes and have been reported to boost xylA activity [26, 27]. Specifically, Santos et al. [26] found that inactivation of the ISU1 gene, which encodes a scaffold protein involved in the assembly of iron–sulfur clusters, occurred during adaptive evolution and improved xylose fermentation efficiency. Therefore, the fine-tuned cellular metal ion concentrations in XUSE could have led to improved xylose fermentation performance by boosting xylA activity and other cellular processes (Table 3).

Through evolutionary engineering, the transcriptomic landscape of hexose transporters (HXT1–17 and GAL2) was changed to significantly increase HXT14 expression and to greatly decrease the expression of HXT2 and HXT4 (Fig. 7a). In accordance with HXT14, whose expression was increased exceptionally by 16-fold, the transcription of HXT10, GAL2, HXT8, HXT1, and HXT9 increased by 2.9-, 1.7-, 1.5-, 1.4-, and 1.1-fold, respectively. Interestingly, these hexose transporters have previously been shown to be more closely related to xylose-preferred sugar transporters based on evolutionary distances in terms of the G-G/F-XXXG motif among native sugar transporters of S. cerevisiae [28]. In contrast, the most downregulated HXT2 and HXT4 are known to be glucose-preferring hexose transporters with longer evolutionary distances in terms of the G-G/F-XXXG motif [28]. These changes in the transcriptomic profiles of sugar transporters could partially explain the improved xylose fermentation performance with the simultaneous cofermentation of glucose and xylose by XUSE. Until recently, studies have focused on the engineering of HXT1–HXT7 to boost the efficiency of xylose utilization [6, 29]. The transcriptome profiles of XUSE and recent reports on the beneficial roles of HXT11 [30] and HXT14 [31] in improving xylose fermentation performance, however, suggest the need to engineer underexplored sugar transporters to develop xylose-utilizing S. cerevisiae at more advanced levels.

Several genes, including COX5B, CYC7, AAC3, ANB1, and TIR3, which are predominantly induced during anaerobic/hypoxic growth [32, 33], were significantly upregulated in the evolved strain (Fig. 7b and Additional file 2: Table S2). ANB1 (YJR047C), which encodes the translation elongation factor eIF-5A [34], was expressed at a fourfold higher level in XUSE than in XUS. COX5B and CYC7, which are responsible for respiration under anaerobic/hypoxic conditions, were highly upregulated by tenfold (Fig. 7b and Additional file 2: Table S2), while most of the genes associated with the TCA cycle and aerobic respiration were repressed in XUSE (Fig. 6 and Additional file 2: Table S2). Moreover, several transcriptional repressors (ROX1, HAP2, and HAP4) of anaerobic respiratory genes were also decreased by 1.5–4-fold in XUSE (Fig. 7b) [35]. These results suggest that the XUSE strain seemed to have taken an evolutionary path toward enhanced anaerobic growth, thus improving anaerobic fermentation performance with an ethanol yield of 0.43 g/g.

In the ethanol fermentation pathway, enzyme transcripts for ethanol oxidation (encoded by ADH2) decreased significantly in the XUSE strain, while those of ADH4 and PDC5, encoding alcohol dehydrogenase and pyruvate decarboxylase, respectively, increased by 2.5–4-fold (Fig. 6). Among the aldehyde dehydrogenase genes involved in acetate formation, the expression levels of ALD4 and ALD6 were greatly decreased by 8–10-fold. The transcriptional changes in ethanol fermentation and acetate formation pathways could also contribute to the increased metabolic flux toward ethanol production in the XUSE strain.

Among the top 20 transcription factors affecting the highest numbers of genes involved in xylose regulation [23], the stress-responsive transcription factors MSN2 and MSN4 showed significantly changed expression levels. Specifically, MSN2 was observed to be downregulated by 2.8-fold, while its homolog MSN4 was upregulated in the evolved strain (2.4-fold, p < 0.05) [36] (Additional file 3: Table S3). This result is consistent with the report by Matsushika et al. [36], in which the expression of MSN4 was induced, while MSN2 transcription was comparable during xylose fermentation and glucose fermentation. In agreement with the increased transcription of MSN4, the transcription of known target genes of MSN2/4, such as DDR2, GSY2, ALD2, ALD3, and CTT1, was upregulated. Interestingly, however, some MSN2/4 target genes of SSA3 and TKL2 were repressed, suggesting a higher influence of MSN2 on the regulation of these genes. Although MSN2/4 is known to be functionally redundant, gene- and stress condition-specific regulatory contributions of MSN2/4 have been previously reported, supporting the downregulated gene expression of the MSN2/4-dependent genes of SSA3 and TKL2 (Additional file 3: Table S3) [37, 38]. Another stress response protein of HSP30, reported to be independent of MSN2/4 [39], was greatly induced (by 32-fold) in XUSE (Additional file 2: Table S2). Since HSP30 acts as a negative regulator of the H+-ATPase Pma1 pump, its induction could have led to the downregulation of the stress-stimulated H+-ATPase [40]. This result suggests that the adaptation of the XUSE strain to glucose limitation or other energy-demanding stresses may limit ATP usage by ATPase, thus decreasing the energy requirement for maintenance during xylose fermentation [40].

Evolutionary paths toward the enhanced xylose fermentation of XI-based strains

To understand the evolutionary trajectories of isomerase-based xylose-fermenting strains, the transcriptional landscapes of evolved xylose-fermenting strains harboring redox-neutral xylose isomerase and cofactor-imbalanced oxidoreductase-based pathways (XI-based strains and XR/XDH-based strains, respectively) were compared (Additional file 4: Figure S1). The most pronounced difference between the XI- and XR/XDH-based strains was the transcription levels of the genes involved in the nonoxidative PP pathway. As shown in Additional file 4: Figure S1, nonoxidative PP pathway enzymes were downregulated (or rearranged) to reduce their transcriptional burdens in XI-based strains [24, 41]. Since the limited metabolic flux through the PP pathway is a known bottleneck for efficient xylose fermentation, strain engineering for enhanced xylose metabolism often involves overexpression of the genes in the nonoxidative PP pathway [15, 24]. Although XKS1 and TAL1 were rationally overexpressed in the XUS strain, evolutionary engineering led to the downregulation of their transcription to maintain the balance of the PP and glycolytic pathways (Table 3). In agreement with the results of this study, Qi et al. [24] reported that the evolutionary process repressed the transcription of TKL1 and TKL2 to optimize xylose metabolism in the XI-based recombinant strain. However, XR/XDH-based strains have evolved to increase the expression levels of XYL1, XYL2, XKS1, and both oxidative and nonoxidative PP pathway genes (TKL1, TAL1, SOL1, SOL3, and GND1) [42, 43]. The cellular responses distinctively support a newly introduced xylose assimilation pathway. Whereas XR/XDH-based strains differentially express the genes involved in redox metabolism, because the first two steps of xylose utilization impose an anaerobic redox imbalance [42], XI-based strains show genomic and transcriptomic changes associated with metal homeostasis to support maximal XI activity (Additional file 4: Figure S1b). Specifically, while the XR/XDH strains tend to show higher expression levels of redox balance-related genes (e.g., NDE1, ZWF1, and GND2) on xylose than on glucose [44, 45], significant changes in those genes were not observed in XI-based strains. As distinguishing characteristics that are seemingly necessary for microaerobic growth of the XI pathway-based strains on xylose, the decreased transcription of a number of genes encoding the TCA cycle and respiratory enzymes was observed only in XI-based strains (Fig. 6) (this study and [24]). The changes in the transcript levels of respiratory enzymes imply that the evolved strains exhibit anaerobic characteristics and require a lower level of maintenance energy during cell growth on xylose than the original strains [24, 45]. One suggestion is that reducing the maintenance energy requirement of the xylose-metabolizing strains is crucial for improving xylose-based ethanol production [23, 45].

Conclusions

In this study, we successfully developed a high-performance xylose-fermenting strain of S. cerevisiae, XUSE, through CRISPR–Cas9-mediated rational engineering and evolutionary engineering. XUSE exhibited comparable xylose fermentation performance to that of SXA-R2P-E, one of the best xylose-fermenting S. cerevisiae strains, with good cofermentation of glucose and xylose. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of XUSE uncovered a new engineering target, ASC1, and provided isomerase-based strain-specific engineering strategies to further improve xylose utilization in S. cerevisiae. With room for further engineering, XUSE could serve as a promising platform strain for lignocellulosic biorefinery.

Methods

Strains and culture conditions

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. S. cerevisiae strain BY4741 was used as a host strain and routinely cultivated at 30 °C in yeast synthetic complete (YSC) medium including 20 g/L glucose (or xylose), 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA), and CSM–His–Ura (complete synthetic medium without His and Ura) or CSM (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio, USA). E. coli strain D10β was used for cloning and plasmid harvest and cultured at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin. All cultivations were performed in orbital shakers at 200 rpm.

Analytical methods

Cell growth was analyzed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm using a Cary 60 Bio UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, USA). The concentration of glucose and xylose was quantified by a high-performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC 1260 Infinity, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) equipped with a refractive index detector (RID) and using a Hi-Plex H column (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) under the following conditions: 5 mM H2SO4 as the mobile phase, a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min, and a column temperature of 65 °C. The ethanol concentration was determined by a gas chromatography (GC) system equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) using an HP-INNOWax polyethylene glycol column (30 m × 0.25 µm × 0.25 µm) (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA).

Construction of xylose-utilizing strain using CRISPR–Cas9

To construct the rationally engineered S. cerevisiae strain, CRISPR–Cas9-based gene integration was performed using the plasmids listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The CRISPR–Cas9 system was slightly modified from that in a previous paper [46] as follows. (i) p413-Cas9 was constructed from the p414-TEF1p-Cas9-CYC1t plasmid (Addgene plasmid #43802). (ii) The gRNA expression plasmid (p426gGRE3 or p426gPHO13) targeting GRE3 (GCCCGGTACGTATCTATGAT) or PHO13 (TTCAATCATGGAGCCTGCAC) was modified by replacing the target sequence of the previous gRNA expression plasmid (Addgene #43803) [46] (Additional file 1: Table S1). The p413-Cas9 plasmid was first cotransformed with a p426PHO13 plasmid and donor DNA fragments containing an overexpression cassette of xylA3* [47] and XKS1 (GPDp-xylA3*-PRM9t-TEFp-XKS1-CYC1t) into the BY4741 strain using a Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation II Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Then, an additional copy of each of xylA3* and TAL1 (GPDp-xylA3*-PRM9t-TEFp-TAL1-CYC1t) was integrated into the gre3 locus by cotransforming p413-Cas9 and p426gGRE3, resulting in the XUS strain. The final strain (XUS) was subjected to subculture on CSM supplemented with 20 g/L glucose for plasmid rescue after integration was verified by PCR-based diagnosis.

Evolutionary engineering of xylose-utilizing strain

To improve the xylose utilization of the rationally engineered strain (XUS), evolutionary engineering was applied by subculturing in 50 mL falcon tubes containing CSM medium supplemented with 20 g/L xylose with an initial OD600 of 0.2. To achieve the most effective and fastest growth selection, cells were serially transferred into fresh medium at the exponential phase (OD600 from 2 to 2.5) using 0.5% inoculum in biological triplicates [15]. After nine rounds of subcultures, the 100 largest colonies were isolated. The cell growth of the isolated variants was first evaluated using TECAN Infinite Pro 200 (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland), and they were then screened in 3 mL of CSM medium with 20 g/L xylose in a 14 mL culture tube. Finally, the fastest growing strain, XUSE, was selected in fermentation experiments using serum bottles under microaerobic conditions.

Phenotypic characterization of the XUSE strain

The XUSE strain was phenotypically characterized by its xylose fermentation and cofermentation performance. For fermentation, seed culture was prepared in YSC medium containing 20 g/L glucose by inoculation with a glycerol stock. Cells were then transferred to fresh YSC medium containing xylose or xylose/glucose as carbon sources and incubated aerobically at 30 °C for 1.5 days for preculture. The precultured cells were then transferred into YSC medium (pH 5.0) containing 100 mM phthalate buffer (pH 5.0). The microaerobic fermentations were conducted in 250 mL serum bottles with an initial OD600 of 0.2, 2, or 10 at 30 °C with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. The serum bottles containing 40 mL of media were capped with rubber stoppers, which were pierced with a needle.

Genotypic characterization of the XUSE strain

The genomic DNA of the XUS and XUSE strains was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, WI, USA). Whole-genome sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform by the service from Macrogen, Inc., South Korea. The whole-genome sequences of XUS and XUSE strains were compared to discover genetic changes in XUSE, and several genes of interest were selected and verified by Sanger sequencing. In the evolved strain, we identified the genes PMR1 and ASC1 those might be responsible for improved xylose utilization. For the functional analysis of the identified mutations in PMR1 and ASC1, the P11 (P1 ∆pmr1) and P12 (P1 ∆asc1) strains derived from the P1 strain (BY4741 ∆gre3 ∆pho13) by the CRISPR–Cas9 editing system were used to construct the P111, P112, P113, P121, P122, and P123 strains, as listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Transcriptomic characterization of the XUSE strain

RNA-sequencing analyses were performed using tools from the commercial RNA-Seq service Ebiogen, Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). After 20 h microaerobic fermentations with xylose as the sole carbon source, yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation at 500×g and 4 °C for 5 min. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol provided by Ebiogen, Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Each of the total RNA samples was evaluated for RNA quality control based on the 28S/18S ratio and RIN measured on the 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). The cDNA library was constructed using the Clontech SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). High-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The raw sequence data of XUS and XUSE have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series Accession Number GSE116076.

References

Jansen MLA, Bracher JM, Papapetridis I, Verhoeven MD, de Bruijn H, de Waal PP, van Maris AJA, Klaassen P, Pronk JT. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for second-generation ethanol production: from academic exploration to industrial implementation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017;17:fox044.

Kwak S, Jin YS. Production of fuels and chemicals from xylose by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a review and perspective. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:82.

Ko JK, Jung JH, Altpeter F, Kannan B, Kim HE, Kim KH, Alper HS, Um Y, Lee SM. Largely enhanced bioethanol production through the combined use of lignin-modified sugarcane and xylose fermenting yeast strain. Bioresour Technol. 2018;256:312–20.

Sheng J, Feng X. Metabolic engineering of yeast to produce fatty acid-derived biofuels: bottlenecks and solutions. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:554.

Wang M, Chen B, Fang Y, Tan T. Cofactor engineering for more efficient production of chemicals and biofuels. Biotechnol Adv. 2017;35:1032–9.

Ko JK, Lee SM. Advances in cellulosic conversion to fuels: engineering yeasts for cellulosic bioethanol and biodiesel production. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;50:72–80.

Brat D, Weber C, Lorenzen W, Bode HB, Boles E. Cytosolic re-localization and optimization of valine synthesis and catabolism enables increased isobutanol production with the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:65.

Ishida N, Saitoh S, Tokuhiro K, Nagamori E, Matsuyama T, Kitamoto K, Takahashi H. Efficient production of l-lactic acid by metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a genome-integrated l-lactate dehydrogenase gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1964–70.

Kim SJ, Seo SO, Jin YS, Seo JH. Production of 2,3-butanediol by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioresour Technol. 2013;146:274–81.

Turner TL, Zhang GC, Kim SR, Subramaniam V, Steffen D, Skory CD, Jang JY, Yu BJ, Jin YS. Lactic acid production from xylose by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae without PDC or ADH deletion. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:8023–33.

Guo W, Sheng J, Zhao H, Feng X. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to produce 1-hexadecanol from xylose. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:24.

Runquist D, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Bettiga M. Increased ethanol productivity in xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae via a randomly mutagenized xylose reductase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:7796–802.

Zhou H, Cheng JS, Wang BL, Fink GR, Stephanopoulos G. Xylose isomerase overexpression along with engineering of the pentose phosphate pathway and evolutionary engineering enable rapid xylose utilization and ethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2012;14:611–22.

Kuyper M, Hartog MM, Toirkens MJ, Almering MJ, Winkler AA, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT. Metabolic engineering of a xylose-isomerase-expressing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain for rapid anaerobic xylose fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005;5:399–409.

Lee SM, Jellison T, Alper HS. Systematic and evolutionary engineering of a xylose isomerase- based pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for efficient conversion yields. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:122.

Tsai CS, Kong II, Lesmana A, Million G, Zhang GC, Kim SR, Jin YS. Rapid and marker-free refactoring of xylose-fermenting yeast strains with Cas9/CRISPR. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112(11):2406–11.

Mandal D, Woolf TB, Rao R. Manganese selectivity of pmr1, the yeast secretory pathway ion pump, is defined by residue gln783 in transmembrane segment 6. Residue Asp778 is essential for cation transport. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23933–8.

Verhoeven MD, Lee M, Kamoen L, van den Broek M, Janssen DB, Daran JG, van Maris AJ, Pronk JT. Mutations in PMR1 stimulate xylose isomerase activity and anaerobic growth on xylose of engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae by influencing manganese homeostasis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46155.

Lee M, Rozeboom HJ, de Waal PP, de Jong RM, Dudek HM, Janssen DB. Metal dependence of the xylose isomerase from Piromyces sp. E2 explored by activity profiling and protein crystallography. Biochemistry. 2017;56:5991–6005.

Zeller CE, Parnell SC, Dohlman HG. The RACK1 ortholog Asc1 functions as a G-protein β subunit coupled to glucose responsiveness in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25168–76.

Chantrel Y, Gaisne M, Lions C, Verdière J. The transcriptional regulator Hap1p (Cyp1p) is essential for anaerobic or heme-deficient growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: genetic and molecular characterization of an extragenic suppressor that encodes a WD repeat protein. Genetics. 1998;148(2):559–69.

Hoffmann B, Mösch HU, Sattlegger E, Barthelmess IB, Hinnebusch A, Braus GH. The WD protein Cpc2p is required for repression of Gcn4 protein activity in yeast in the absence of amino-acid starvation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:807–22.

Feng X, Zhao H. Investigating host dependence of xylose utilization in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains using RNA-seq analysis. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:96.

Qi X, Zha J, Liu GG, Zhang W, Li BZ, Yuan YJ. Heterologous xylose isomerase pathway and evolutionary engineering improve xylose utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1165.

Jensen LT, Ajua-Alemanji M, Culotta VC. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae high affinity phosphate transporter encoded by PHO84 also functions in manganese homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42036–40.

dos Santos LV, Carazzolle MF, Nagamatsu ST, Sampaio NMV, Almeida LD, Pirolla RAS, Borelli G, Corrêa TLR, Argueso JL, Pereira GAG. Unraveling the genetic basis of xylose consumption in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38676.

Rouault TA, Tong WH. Iron–sulphur cluster biogenesis and mitochondrial iron homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:345–51.

Young EM, Tong A, Bui H, Spofford C, Alper HS. Rewiring yeast sugar transporter preference through modifying a conserved protein motif. PNAS. 2014;111:131–6.

Apel AR, Ouellet M, Szmidt-Middleton H, Keasling JD, Mukhopadhyay A. Evolved hexose transporter enhances xylose uptake and glucose/xylose co-utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19512.

Shin HY, Nijland JG, de Waal PP, Driessen AJM. The amino-terminal tail of Hxt11 confers membrane stability to the Hxt2 sugar transporter and improves xylose fermentation in the presence of acetic acid. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114:1937–45.

Wang M, Li S, Zhao H. Design and engineering of intracellular-metabolite-sensing/regulation gene circuits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:206–15.

Kwast KE, Burke PV, Brown K, Poyton RO. REO1 and ROX1 are alleles of the same gene which encodes a transcriptional repressor of hypoxic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1997;32:377–83.

Burke PV, Raitt DC, Allen LA, Kellogg EA, Poyton RO. Effects of oxygen concentration on the expression of cytochrome c and cytochrome c oxidase genes in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14705–12.

Saini P, Eyler DE, Green R, Dever TE. Hypusine-containing protein eIF5A promotes translation elongation. Nature. 2009;459:118–21.

Zhang T, Bu P, Zeng J, Vancura A. Increased heme synthesis in yeast induces a metabolic switch from fermentation to respiration even under conditions of glucose repression. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:16942–54.

Matsushika A, Goshima T, Hoshino T. Transcription analysis of recombinant industrial and laboratory Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains reveals the molecular basis for fermentation of glucose and xylose. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:16.

Berry DB, Gasch AP. Stress-activated genomic expression changes serve a preparative role for impending stress in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4580–7.

AkhavanAghdam Z, Sinha J, Tabbaa OP, Hao N. Dynamic control of gene regulatory logic by seemingly redundant transcription factors. eLife. 2016;5:e18458.

Schüller C, Mamnun YM, Mollapour M, Krapf G, Schuster M, Bauer BE, Piper PW, Kuchler K. Global phenotypic analysis and transcriptional profiling defines the weak acid stress response regulon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:706–20.

Piper PW, Ortiz-Calderon C, Holyoak C, Coote P, Cole M. Hsp30, the integral plasma membrane heat shock protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is a stress-inducible regulator of plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1997;2:12–24.

Li YC, Zeng WY, Gou M, Sun ZY, Xia ZY, Tang YQ. Transcriptome changes in adaptive evolution of xylose-fermenting industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains with δ-integration of different xylA genes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:7741–53.

Wahlbom CF, Cordero Otero RR, van Zyl WH, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Jönsson LJ. Molecular analysis of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant with improved ability to utilize xylose shows enhanced expression of proteins involved in transport, initial xylose metabolism, and the pentose phosphate pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:740–6.

Sonderegger M, Jeppsson M, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Sauer U. Molecular basis for anaerobic growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on xylose, investigated by global gene expression and metabolic flux analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2307–17.

Zeng WY, Tang YQ, Gou M, Xia ZY, Kida K. Transcriptomes of a xylose-utilizing industrial flocculating Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain cultured in media containing different sugar sources. AMB Express. 2016;6:51.

Jin YS, Laplaza JM, Jeffries TW. Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered for xylose metabolism exhibits a respiratory response. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6816–25.

DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, Church GM. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR–Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4336–43.

Lee SM, Jellison T, Alper HS. Directed evolution of xylose isomerase for improved xylose catabolism and fermentation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5708–16.

Ko JK, Um Y, Woo HM, Kim KH, Lee SM. Ethanol production from lignocellulosic hydrolysates using engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae harboring xylose isomerase-based pathway. Bioresour Technol. 2016;209:290–6.

Casey E, Sedlak M, Ho NW, Mosier NS. Effect of acetic acid and pH on the cofermentation of glucose and xylose to ethanol by a genetically engineered strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:385–93.

Romaní A, Pereira F, Johansson B, Domingues L. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ethanol strains PE-2 and CAT-1 for efficient lignocellulosic fermentation. Bioresour Technol. 2015;179:150–8.

Walfridsson M, Hallborn J, Penttilä M, Keränen S, Hahn-Hägerdal B. Xylose-metabolizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains overexpressing the TKL1 and TAL1 genes encoding the pentose phosphate pathway enzymes transketolase and transaldolase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61(12):4184–90.

Kuyper M, Toirkens MJ, Diderich JA, Winkler AA, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT. Evolutionary engineering of mixed-sugar utilization by a xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005;5:925–34.

Nijland JG, Vos E, Shin HY, de Waal PP, Klaassen P, Driessen AJM. Improving pentose fermentation by preventing ubiquitination of hexose transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:158.

Kim B, Du J, Eriksen DT, Zhao H. Combinatorial design of a highly efficient xylose-utilizing pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of cellulosic biofuels. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:931–41.

Krahulec S, Petschacher B, Wallner M, Longus K, Klimacek M, Nidetzky B. Fermentation of mixed glucose–xylose substrates by engineered strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: role of the coenzyme specificity of xylose reductase, and effect of glucose on xylose utilization. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:16.

Matsushika A, Sawayama S. Effect of initial cell concentration on ethanol production by flocculent Saccharomyces cerevisiae with xylose-fermenting ability. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;162:1952–60.

Sonderegger M, Jeppsson M, Larsson C, Gorwa-Grauslund MF, Boles E, Olsson L, Spencer-Martins I, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Sauer U. Fermentation performance of engineered and evolved xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:90–8.

Xiong M, Chen G, Barford J. Alteration of xylose reductase coenzyme preference to improve ethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae from high xylose concentrations. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:9206–15.

Zaldivar J, Borges A, Johansson B, Smits HP, Villas-Bôas SG, Nielsen J, Olsson L. Fermentation performance and intracellular metabolite patterns in laboratory and industrial xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59:436–42.

Authors’ contributions

PTNH and JKK conducted the experimental work, and contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript. GG and YU reviewed and commented on the manuscript. SML conceived the study, interpreted the research results, and contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by a National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) under a grant from the government of Korea (MSIP) (No. CAP-11-04-KIST) and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. 2017R1A6A3A04009462). The authors also appreciate further support by the New & Renewable Energy Core Technology Program of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), granted financial resources by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy, Republic of Korea (No. 20153030091360).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Metabolism-related genes with significantly changed expression levels in XUSE relative to those in XUS.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Expression levels of known target genes dependent on Msn2/4p.

Additional file 4: Figure S1.

Comparison of the trends in the transcriptional changes in XI-based (a) and XR/XDH-based (b) strains during adaptive evolution on xylose.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran Nguyen Hoang, P., Ko, J.K., Gong, G. et al. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of a refactored xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain for lignocellulosic biofuel production. Biotechnol Biofuels 11, 268 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-018-1269-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-018-1269-7

), 20–20 (

), 20–20 (

), 20–30 (

), 20–30 (

), and 20–40 (

), and 20–40 (

). *p < 0.01 vs 20–0

). *p < 0.01 vs 20–0