Abstract

Background

In a stepped wedge, cluster randomised trial, clusters receive the intervention at different time points, and the order in which they received it is randomised. Previous systematic reviews of stepped wedge trials have documented a steady rise in their use between 1987 and 2010, which was attributed to the design’s perceived logistical and analytical advantages. However, the interventions included in these systematic reviews were often poorly reported and did not adequately describe the analysis and/or methodology used. Since 2010, a number of additional stepped wedge trials have been published. This article aims to update previous systematic reviews, and consider what interventions were tested and the rationale given for using a stepped wedge design.

Methods

We searched PubMed, PsychINFO, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Web of Science, the Cochrane Library and the Current Controlled Trials Register for articles published between January 2010 and May 2014. We considered stepped wedge randomised controlled trials in all fields of research. We independently extracted data from retrieved articles and reviewed them. Interventions were then coded using the functions specified by the Behaviour Change Wheel, and for behaviour change techniques using a validated taxonomy.

Results

Our review identified 37 stepped wedge trials, reported in 10 articles presenting trial results, one conference abstract, 21 protocol or study design articles and five trial registrations. These were mostly conducted in developed countries (n = 30), and within healthcare organisations (n = 28). A total of 33 of the interventions were educationally based, with the most commonly used behaviour change techniques being ‘instruction on how to perform a behaviour’ (n = 32) and ‘persuasive source’ (n = 25). Authors gave a wide range of reasons for the use of the stepped wedge trial design, including ethical considerations, logistical, financial and methodological. The adequacy of reporting varied across studies: many did not provide sufficient detail regarding the methodology or calculation of the required sample size.

Conclusions

The popularity of stepped wedge trials has increased since 2010, predominantly in high-income countries. However, there is a need for further guidance on their reporting and analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

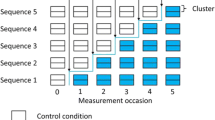

Methods for designing, analysing and reporting cluster randomised trials are now well established [1, 2]. A potential alternative to randomising clusters to a simple treatment or control condition is to randomly allocate the time at which clusters receive an intervention. This is termed a ‘stepped wedge’ trial design. Consequently, all clusters have received the intervention by the end of the trial. Other terms for this trial design found in the literature include experimentally staged introduction, delayed intervention and phased implementation trials. A stepped wedge trial based on randomising the time at which individuals, rather than clusters, receive the intervention is possible, but uncommon in the literature [3].

Two systematic reviews have been published on stepped wedge randomised controlled trials (SWTs). The first was conducted by Brown and Lilford [4] in March 2006 and identified 12 protocols or articles. They included both randomised and non-randomised studies, and those with allocations at individual and cluster level. However, they limited the review to the health sector. They concluded that there were regularities in the motivation for adopting the stepped wedge design, but that the methodological descriptions of studies, including the sample size calculations and analytical methods, were not always complete. Sample size calculations were reported in only five out of 12 studies, and there was considerable variation in the analytical methods applied.

Mdege et al. [5] updated Brown and Lilford’s review and expanded the search to include non-healthcare trials, but focussed only on randomised studies with cluster allocations. They retrieved 25 articles up to January 2010. Common reasons given for choosing a stepped wedge design were perceived methodological and logistical benefits, as well as improved social acceptability based on the premise that every cluster would eventually receive the intervention. Mdege et al. also identified problems with the clarity of reporting and analysis.

These systematic reviews concluded that the stepped wedge design was gaining in popularity, but that the studies were often poorly reported. The use of the stepped wedge design in randomised controlled trials is likely to have increased after the publication of articles by Hussey and Hughes [6] and Moulton et al. [7] in 2007, which described sample size calculations and analytical methods for SWTs involving dichotomous and/or continuous outcomes, and survival data. Poor reporting likely results from the lack of standardised Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines [8, 9].

There have been additional publications on the reporting, analysis and/or sample size calculations for SWTs [10–12] since Mdege et al.’s review [5]. At the same time, controversy around the use of this design has increased in the literature. Some authors have raised objections to the reasons given for conducting SWTs. For example, Kotz et al. [13] argued that the ability to roll out an intervention to all clusters for ethical reasons is not an inherent property of SWTs, and should not form the basis of choice over a traditional parallel cluster randomised controlled trials: it is possible to have a wait-list control group in a cluster randomised controlled trial, or to implement the intervention in the control group if beneficial effects are found. Other concerns raised by researchers include the often longer duration of SWTs, the possibility of increased drop-out rates due to repeated measurements and a concern that an intervention may be implemented in all clusters, which has not yet been proven to be effective. There is also an active debate in the literature about the conditions under which SWTs may have greater or less statistical power than parallel trials [9, 14, 15]. Mdege et al. have subsequently agreed with many of these arguments, however, they have also pointed out that although they may hold for the evaluation of healthcare treatments, they do not generally hold for policy-type trials, for which the alternative is often no randomised trial at all [16]. These issues are discussed in more detail in the other papers which make up this special issue of trials [17–19].

As part of this collection of articles on SWTs, we updated previous systematic reviews to:

-

1.

Determine how many protocols and articles have subsequently been recorded,

-

2.

Describe the areas of study and countries in which the design was most commonly used,

-

3.

Identify the types of intervention which have been evaluated using SWTs,

-

4.

Examine the stated reasons for conducting SWTs,

-

5.

Identify the main design features, and

-

6.

Describe the methods used to calculate sample sizes and to analyse data.

The current paper focuses on objectives one to three (Additional file 1 sections: 1.1-1.3, 2.1-2.3, 2.6-2.8, 3.1, 3.2, 3.5-3.9, 3.12-3.14, 5.1-5.3). Objectives four to six are considered in more detail in the other articles in this issue of Trials.

Methods

Literature search

We searched the following sources: PubMed, PsycINFO, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Web of Science, the Cochrane Library and the Current Controlled Trials Register. The search was conducted on 14 May 2014, and was limited to studies published or registered since 1 January 2010 and written in English. The search terms were any of the following in the abstract: ‘stepped wedge’, ‘step wedge’, ‘experimentally staged introduction’, ‘delayed intervention’ or ‘one directional cross over design’. All articles, conference abstracts, protocols and trial registrations of original randomised research studies that used or planned to use a stepped wedge design, from any field of research, were eligible. We excluded studies retrospectively analysed as a stepped wedge design when the study was not originally designed as a stepped wedge. Where original articles for studies included in the Mdege review as protocols had been published, the published articles were considered for inclusion. We also reviewed methodological and design articles on SWTs published since Mdege et al. [5] in order to understand current methodological debates. Some of these articles were identified through the formal literature search detailed above, and others by checking the reference lists of identified articles. These are reviewed in the other publications of this special issue of Trials [17–19].

Review of studies

One author (AP) reviewed the titles and abstracts of all identified research articles, conference abstracts, protocols and trial registrations to decide on eligibility for full review. Another author (EB) then re-ran the search to double check that all eligible papers had been identified between 1 January 2010 and 14 May 2014. Pairs of authors then reviewed the full texts of selected articles. Studies subsequently identified as non-randomised or not a SWT, regardless of how they were described by study authors, were then removed. Any additional studies known to the authors of this article that met the eligibility criteria above were also included.

Data extraction and analysis

Pairs of authors reviewed the full texts of articles screened by AP and used a standardised data extraction form to extract key information on each study (see Additional file 1). Relevant sections of these forms were then collated for this article by two authors (EB and JL). Additional, sections were collated by authors of the other papers in this special issue of Trials [17, 19, 18]. For conference abstracts or trial registrations, a number of these sections were not relevant and were coded as ‘not applicable’. Discrepancies between pairs of completed forms were resolved through discussions between EB and co-authors.

In order to characterise the types of interventions tested through SWTs, we categorised all interventions using the functions described by the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework [20]. Although many frameworks are available to categorise interventions (for example, MINDSPACE [21]), these have been criticised for their lack of comprehensibility and their conceptual incoherence [20]. The BCW stipulates nine types of intervention functions, which can be applied to various policy categories including regulation, fiscal measures, guidelines, environmental and social planning, communication and marketing, legislation and service provision. These nine functions are as follows: 1) education (increasing knowledge or understanding, for example, providing information to promote healthy eating), 2) persuasion (using communication to produce feelings that stimulate action, for example, using imagery to motivate increases in physical activity), 3) incentivisation (creating expectation of a reward, for example, using prize draws to increase medication adherence), 4) training (imparting skills, for example, training to increase safe cycling), 5) restriction (using rules to reduce the opportunity to engage in the behaviour of interest, for example, prohibiting the sale of solvents to those under 18-years-old), 6) environmental restructuring (changing the physical or social context, for example, providing free at-home gym equipment), 7) modelling (providing an example for people to imitate, for example, using television drama scenes to promote safe sex), 8) enablement (reducing barriers to an individual’s capability or opportunity, for example, medication for cognitive deficits) and 9) coercion (creating expectation of punishment or increasing cost, for example, raising the cost of cigarettes to reduce consumption). EB coded all interventions using these nine functions. A subset of papers was also coded by a researcher familiar with the BCW, until 90 % agreement was obtained. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions. For interventions using the education function, we specified whether this was for the client or healthcare professional.

EB then used a taxonomy of 93 Behaviour Change Techniques (BCT Taxonomy v1) [22], to describe the components of each intervention. Guidelines from Michie et al. [22, 23] were followed, including only coding BCTs when there was unequivocal evidence of their inclusion in a given intervention. The taxonomy includes a standard definition of, and detailed coding instructions for each BCT, including examples of instances in which each BCT should or should not be coded.

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 describes the selection of studies included in this systematic review. Of the 2,948 records retrieved from the database search, we reviewed 47 full texts, and 36 studies were eligible for this review. In addition, the authors of this paper identified one more paper not found in the database search (as it is an SWT, but also refers to ‘stepped expansion’ in the abstract). Four of the published papers had previously been included as published protocols in the Mdege et al. review [5].

These 37 studies consisted of 10 articles presenting trial results, one conference abstract, 21 protocol or design articles and five trial registrations (Table 1) [24–62]. It is clear from Fig. 2 that the rate of publications on SWTs has increased between 2010 and 2014.

Study characteristics

Randomisation was at the cluster level in 36 of 37 trials, with one being individually randomised in a two-step SWT [50]. There were 11 studies based in the United Kingdom, five in Australia, four in the Netherlands, three in Canada, two in Brazil, two in France and 10 based in other countries (Denmark, Germany, India, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Syria, United States and Zambia). A total of 28 studies were conducted within healthcare organisations (for example, general practices and hospitals), four were based in the community, two within schools, one within the prison-service, one in the workplace and one within supermarkets. The median length of the trials was 18 months (range 4 to 96 months) and the median number of clusters was 17 (range: 4 to 128 clusters; one trial did not state the number of clusters).

Design

There were 13 trials that used a continuous recruitment short exposure design, which involves the continuous recruitment of participants as they become available and exposure to either the control or intervention condition (but usually not both) for a short period, typically common to all participants. Generally, measures were taken on a one-off basis for each participant.

There were 11 studies that used a closed cohort design, whereby all participants are identified at baseline and most or all experience both the control and the intervention. Generally, measures were either time-to-event or taken repeatedly at regular intervals. Another 11 studies adopted an open cohort design. These were most often community-based interventions. Many participants are exposed from the start of the study using this design, but some will leave the study, while others may join. Thus, although many experience both the control and the intervention, some will only experience one. Generally, these studies used cross-sectional surveys at the beginning and end of each step.

Two studies had different designs to the three types outlined above. For further details see the design paper in this collection [18]. Simple randomisation for the order of intervention roll-out was the most common randomisation method (n = 17), followed by stratified (n = 13) and restricted (n = 1) randomisation. Six trials did not report the randomisation method clearly.

Intervention features

Numerous behaviours were targeted, including academic achievement and attendance, blood pressure, depression and hand hygiene (see Additional file 2). Using the functions of the BCW [15], thirty-three of the interventions included educational based components, four used persuasion, four used incentivisation, twenty used training (that is, imparted skills), eight used environmental restructuring, six used enablement, three used modelling and one used coercion. None were based on the function restriction. In 20 of the 33 trials with education components, the education was applied to healthcare professionals, in 12 trials it was applied to the client (for example, the patient) and in one trial the education component was applied to a mixture of people. The most commonly used BCTs were ‘instruction on how to perform a behaviour’ (n = 32), ‘persuasive source’ (n = 25), ‘adding objects to the environment’ (n = 14) and ‘restructuring the physical environment’ (n = 13).

Reasons for use

A variety of reasons were given for adopting the SWT design, including ethical, logistical and methodological and/or analytic reasons (see Table 1). In 21 studies, authors felt that the logistical barriers to simultaneously implementing the intervention in many clusters were too high, and so opted for a stepped wedge design. In 16 studies, authors described a lack of equipoise for the intervention based on positive pilot study results or prior literature, and felt it would be unethical to deny the intervention to some groups. Another reason cited in eight trials was to avoid the ‘disappointment effects’ possible in a parallel trial, that is, to avoid some clusters dropping out of the study when randomised to the control arm. Since all clusters would receive the intervention at some point, this was thought by some to increase the motivation of health staff to participate. Two trials stated that the intervention was going to be rolled out to all clusters anyway.

Seven studies reported that the stepped wedge design would have higher statistical power, with five explicitly stating that this was because clusters would act as their own controls. Seven studies also reported that the ability to adjust for time trends in outcomes was an advantage. Six trials gave no explanation for adopting a stepped wedge design (including the one conference abstract and three trial registrations).

Sample size calculations

Six of the studies did not report sample size calculations, or it was unclear whether they had been performed (including the one conference abstract and four trial registrations). Of those that did report sample size calculations, nine used a design effect for parallel or cluster randomised controlled trials. Those accounting for the stepped wedge design most commonly used the approach recommended by Hussey and Hughes [6]. One study used the design effect defined by Woertman et al. [10], and one used the method proposed by Moulton et al. [7]. Three trials used simulations to compute the sample size. The sample size calculations need to take the proposed analysis method into account, and these are complicated for stepped wedge trials; for further details see the sample size and analysis articles in this collection [17, 19].

Discussion

The number of trials using stepped wedge designs appears to be increasing over time, with 37 new trials published or planned since the 25 identified in a previous review [5]. The trials identified in this latest review were mostly conducted in developed countries, in the health sector, and offered ethical, logistical and methodological reasons for adopting the design. Most interventions tested involved increasing knowledge through education or training, whether among staff providing a service or among clients, an effect which could be difficult to ‘remove’ in a two-way cross-over design (a design which randomises half the clusters to intervention and half to control for the first half of the trial, at which point they switch condition until the end of the trial [63]). However, the reporting of trial design and sample size calculations was generally poor.

There are some limitations to our review: we only included articles published in English and used only one trial register. We also did not search the reference lists of included studies. Another possible limitation is that we only focussed on studies published or registered since 1 January 2010. However, we wanted the review to reflect current practice and feel this choice is justified. In addition, we excluded studies (both implicitly through our search criteria and explicitly during full-text review) that did not use common terminology, and so may have missed some SWTs.

The rise in the number of studies adopting a stepped wedge design since 2010 could be a consequence of the publication of a handful of pivotal articles on sample size calculations and/or analysis of SWTs [6, 7, 10–12]. However, in line with the conclusions of Mdege et al. [5], some poor reporting remains. Clear descriptions were not always given for the rationale for using the stepped wedge design, the details of the design (including method of randomisation) or sample size calculations. This may partly be due to the lack of coherent recommendations for stepped wedge designs, with authors relying on those published previously for cluster randomised controlled trials. Although CONSORT type guidelines are being produced, these are not due for publication until 2017 [9]. Recommendations for this are beyond the scope of this article, but are discussed further in this collection [18, 19].

The reasons for using a stepped wedge design largely coincide with those reported previously: ethical, logistical and methodological [5, 4]. The potential impact of disappointment effects, whereby individuals not randomised to the treatment of choice fail to adhere or drop out, was given by several studies as a reason for choosing the SWT design (Table 1). However, some authors argue that this is not an inherent feature of SWTs, and that cluster randomised controlled trials can be extended to include a wait-list control group [13]. Thus the ethical argument that one should not withhold a potentially effective intervention from a group of individuals cannot form the sole justification for this trial design. It is possible that under certain circumstances, including the roll out of public health interventions, that a SWT would reduce required resources. One could easily envisage the situation of an intervention conducted by GPs, which would require one intervention trainer for an SWT (each GP is visited consecutively) and multiple for a cluster randomised controlled trial (each GP is trained concurrently). SWTs may also be suitable for optimising interventions, with the ability to modify content and delivery over time. However, the excess expense of this over factorial designs should be considered [64]. Finally, although it is possible under certain circumstances that the SWT design is optimal in terms of power, due partly to the within- and between-cluster data, this is not always the case [17, 14].

In line with the conclusions of Mdege et al. [5], the majority of SWTs we found were conducted in developed countries. However, there was an expansion beyond the earlier focus on nutrition and communicable diseases to a broad range of outcomes, including adverse drug event reporting, carer support and depression. The finding that the majority of interventions involved the functions of education and training is consistent with a previous review of 338 articles reporting on health-behaviour interventions [65]. The reliance on these likely reflects the adoption of common sense models of human behaviour during intervention development, that is, the long-held belief that improving knowledge and skills is sufficient to induce behaviour change in most circumstances [20]. There may also be a belief that education and training can do no harm, making them particularly appropriate to the stepped wedge design, with a lower requirement for equipoise than for a parallel design. However, if this is the case, we feel this may be simplistic, as training and education both come with opportunity costs for the time used to implement, as well as the potential to confuse or overburden participants. In addition, as explained in the third article of this collection (which is concerned with the logistics, ethics and politics of SWTs), we think that equipoise is still required for such trials [66].

All but one of the trials randomised the order of roll-out at the cluster level rather than the individual level. This may reflect the same logistical needs that lay behind the decision to opt for a stepped wedge rather than parallel design. SWTs used multiple designs, with important implications for analysis and sample size. These issues are discussed further in the relevant articles in this collection, but we note that there are several types of SWT and reporting the type of SWT used is important.

It is interesting that the first example of an SWT, the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study [63], was evaluating a new vaccine, yet none of the studies in this review were trialling a new medical intervention. Two studies investigated provision of isoniazid preventive therapy and HIV testing, but both of these were supported by current recommendations. Currently, questions related to equipoise, logistic benefits and increased social acceptability are leading to debates about the possible role of stepped wedge designs in the evaluation of new Ebola vaccines and treatments. In such circumstances, an important distinction may be drawn between vaccines and treatments, whereby vaccines may eventually be delivered to all participants, but treatments may come too late for those in the control condition. Clearly, the use of SWTs is increasing, and with this comes greater variety in trial contexts and designs, requiring further methodological work and guidance for researchers.

Conclusions

This article aims to update previous systematic reviews on SWTs, consider what interventions were tested and the rationale given for using an SWT. The popularity of stepped wedge trials was found to have increased since 2010, predominantly in high-income countries. However, many were poorly reported and thus there is a need for further guidance on the conduction and reporting of SWTs.

Abbreviations

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated standards of reporting trials

- SWT:

-

Stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- BCT:

-

Behaviour change techniques

References

Hayes R, Moulton L. Cluster randomised trials. Pharmaceut Statist. 2009;11:88.

Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328(7441):702–8.

Grant AD, Charalambous S, Fielding KL, Day JH, Corbett EL, Chaisson RE, et al. Effect of routine isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence among HIV-infected men in South Africa: a novel randomized incremental recruitment study. JAMA. 2005;293(22):2719–25.

Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):54.

Mdege ND, Man M-S, Taylor CA, Torgerson DJ. Systematic review of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials shows that design is particularly used to evaluate interventions during routine implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(9):936–48.

Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):182–91.

Moulton LH, Golub JE, Durovni B, Cavalcante SC, Pacheco AG, Saraceni V, et al. Statistical design of THRio: a phased implementation clinic-randomized study of a tuberculosis preventive therapy intervention. Clin Trials. 2007;4(2):190–9.

Ivers N, Taljaard M, Dixon S, Bennett C, McRae A, Taleban J, et al. Impact of CONSORT extension for cluster randomised trials on quality of reporting and study methodology: review of random sample of 300 trials, 2000–8. BMJ. 2011;343:d5886.

Hemming K, Girling A, Haines T, Lilford R. Protocol: Consort extension to stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014. doi:10.1136/bmj.h391.

Woertman W, de Hoop E, Moerbeek M, Zuidema SU, Gerritsen DL, Teerenstra S. Stepped wedge designs could reduce the required sample size in cluster randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):752–8.

Dimairo M, Bradburn M, Walters SJ. Sample size determination through power simulation; practical lessons from a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial (SW CRT). Trials. 2011;12(1):1.

Scott JM, Juraska M, Fay MP, Gilbert PB. Finite-sample corrected generalized estimating equation of population average treatment effects in stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2014. doi:10.1177/0962280214552092.

Kotz D, Spigt M, Arts IC, Crutzen R, Viechtbauer W. Use of the stepped wedge design cannot be recommended: a critical appraisal and comparison with the classic cluster randomized controlled trial design. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(12):1249–52.

Hemming K, Girling A, Martin J, Bond SJ. Stepped wedge cluster randomized trials are efficient and provide a method of evaluation without which some interventions would not be evaluated. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(9):1058–9.

Hemming K, Girling A. The efficiency of stepped wedge vs. cluster randomized trials: stepped wedge studies do not always require a smaller sample size. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(12):1427–8.

Mdege ND, Man M-S, Taylor CA, Torgerson DJ. There are some circumstances where the stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial is preferable to the alternative: no randomized trial at all. Response to the commentary by Kotz and colleagues. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(12):1253–4.

Baio G, Copas A, Ambler G, King M, Beard E, RZ O. Sample size calculation for a stepped wedge trial. Trials.

Copas AJ, Lewis JJ, Thompson, JA, Davey C, Baio G, Hargreaves J. Designing a stepped wedge trial: three main designs, carry-over effects and randomisation approaches. Trials.

Davey C, Hargreaves J, Thompson JA, Copas AJ, Beard E, Lewis JJ, et al. Analysis and reporting of stepped-wedge randomised-controlled trials: synthesis and critical appraisal of published studies. Trials.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, King D, Vlaev D. MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy. London: Cabinet Office and Institute for Government; 2010.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):379.

Bacchieri G, Barros AJ, dos Santos JV, Gonçalves H, Gigante DP. A community intervention to prevent traffic accidents among bicycle commuters. Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44(5):867–75.

Bashour HN, Kanaan M, Kharouf MH, Abdulsalam AA, Tabbaa MA, Cheikha SA. The effect of training doctors in communication skills on women’s satisfaction with doctor–woman relationship during labour and delivery: a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial in Damascus. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e002674.

Durovni B, Saraceni V, Moulton LH, Pacheco AG, Cavalcante SC, King BS, et al. Effect of improved tuberculosis screening and isoniazid preventive therapy on incidence of tuberculosis and death in patients with HIV in clinics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a stepped wedge, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(10):852–8.

Fuller C, Michie S, Savage J, McAteer J, Besser S, Charlett A, et al. The Feedback Intervention Trial (FIT)—improving hand-hygiene compliance in UK healthcare workers: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e41617.

Gruber JS, Reygadas F, Arnold BF, Ray I, Nelson K, Colford JM. A stepped wedge, cluster-randomized trial of a household UV-disinfection and safe storage drinking water intervention in rural Baja California Sur, Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(2):238–45.

Horner C, Wilcox M, Barr B, Hall D, Hodgson G, Parnell P, et al. The longitudinal prevalence of MRSA in care home residents and the effectiveness of improving infection prevention knowledge and practice on colonisation using a stepped wedge study design. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000423.

Mhurchu CN, Gorton D, Turley M, Jiang Y, Michie J, Maddison R, et al. Effects of a free school breakfast programme on children’s attendance, academic achievement and short-term hunger: results from a stepped-wedge, cluster randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(3):257–64.

Kitson AL, Schultz TJ, Long L, Shanks A, Wiechula R, Chapman I, et al. The prevention and reduction of weight loss in an acute tertiary care setting: protocol for a pragmatic stepped wedge randomised cluster trial (the PRoWL project). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):299.

Schultz TJ, Kitson AL, Soenen S, Long L, Shanks A, Wiechula R, et al. Does a multidisciplinary nutritional intervention prevent nutritional decline in hospital patients? A stepped wedge randomised cluster trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2014;9(2):e84–90.

Roy A, Anaraki S, Hardelid P, Catchpole M, Rodrigues LC, Lipman M, et al. Universal HIV testing in London tuberculosis clinics: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(3):627–34.

Stern A, Mitsakakis N, Paulden M, Alibhai S, Wong J, Tomlinson G, et al. Pressure ulcer multidisciplinary teams via telemedicine: a pragmatic cluster randomized stepped wedge trial in long term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):83.

Fearon P, Quinn T, Wright F, Fraser P, McAlpine C, Stott D, editors. Evaluation of a telephone hotline to enhance rapid outpatient assessment of minor stroke or TIA: a stepped wedge cluster randomised control trial, International Journal of Stroke. NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

Bennett PN, Daly RM, Fraser SF, Haines T, Barnard R, Ockerby C, et al. The impact of an exercise physiologist coordinated resistance exercise program on the physical function of people receiving hemodialysis: a stepped wedge randomised control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14(1):204.

Bernabe-Ortiz A, Diez-Canseco F, Gilman RH, Cárdenas MK, Sacksteder KA, Miranda JJ. Launching a salt substitute to reduce blood pressure at the population level: a cluster randomized stepped wedge trial in Peru. Trials. 2014;15(1):93.

Brimblecombe J, Ferguson M, Liberato SC, Ball K, Moodie ML, Magnus A, et al. Stores Healthy Options Project in Remote Indigenous Communities (SHOP@ RIC): a protocol of a randomised trial promoting healthy food and beverage purchases through price discounts and in-store nutrition education. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):744.

Dainty KN, Scales DC, Brooks SC, Needham DM, Dorian P, Ferguson N, et al. A knowledge translation collaborative to improve the use of therapeutic hypothermia in post-cardiac arrest patients: protocol for a stepped wedge randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2011;6:4.

Dreischulte T, Grant A, Donnan P, McCowan C, Davey P, Petrie D, et al. A cluster randomised stepped wedge trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a multifaceted information technology-based intervention in reducing high-risk prescribing of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antiplatelets in primary medical care: the DQIP study protocol. Implement Sci. 2012;7:24.

Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M, Teerenstra S, Leontjevas R, Adang EM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, et al. Act In case of Depression: the evaluation of a care program to improve the detection and treatment of depression in nursing homes, Study Protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):91.

Gucciardi E, Fortugno M, Horodezny S, Lou W, Sidani S, Espin S, et al. Will Mobile Diabetes Education Teams (MDETs) in primary care improve patient care processes and health outcomes? Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13(1):165.

Keriel-Gascou M, Buchet-Poyau K, Duclos A, Rabilloud M, Figon S, Dubois J-P, et al. Evaluation of an interactive program for preventing adverse drug events in primary care: study protocol of the InPAct cluster randomised stepped wedge trial. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):69.

Kjeken I, Berdal G, Bø I, Dager T, Dingsør A, Hagfors J, et al. Evaluation of a structured goal planning and tailored follow-up programme in rehabilitation for patients with rheumatic diseases: protocol for a pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15(1):153.

Marshall T, Caley M, Hemming K, Gill P, Gale N, Jolly K. Mixed methods evaluation of targeted case finding for cardiovascular disease prevention using a stepped wedged cluster RCT. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):908.

Mouchoux C, Rippert P, Duclos A, Fassier T, Bonnefoy M, Comte B, et al. Impact of a multifaceted program to prevent postoperative delirium in the elderly: the CONFUCIUS stepped wedge protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):25.

Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, Koffijberg H, Backus BE, Six AJ, Doevendans PA, et al. The impact of the HEART risk score in the early assessment of patients with acute chest pain: design of a stepped wedge, cluster randomised trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13(1):77.

Praveen D, Patel A, McMahon S, Prabhakaran D, Clifford GD, Maulik PK, et al. A multifaceted strategy using mobile technology to assist rural primary healthcare doctors and frontline health workers in cardiovascular disease risk management: protocol for the SMARTHealth India cluster randomised controlled trial. Communities. 2013;5:6.

Rasmussen CD, Holtermann A, Mortensen OS, Søgaard K, Jørgensen MB. Prevention of low back pain and its consequences among nurses’ aides in elderly care: a stepped-wedge multi-faceted cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1088.

Ratanawongsa N, Handley MA, Quan J, Sarkar U, Pfeifer K, Soria C, et al. Quasi-experimental trial of diabetes Self-Management Automated and Real-Time Telephonic Support (SMARTSteps) in a Medicaid managed care plan: study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):22.

Solomon E, Rees T, Ukoumunne OC, Hillsdon M. The Devon Active Villages Evaluation (DAVE) trial: study protocol of a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial of a community-level physical activity intervention in rural southwest England. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):581.

Stringer JS, Chisembele-Taylor A, Chibwesha CJ, Chi HF, Ayles H, Manda H, et al. Protocol-driven primary care and community linkages to improve population health in rural Zambia: the Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessment (BHOMA) project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S7.

Tirlea L, Truby H, Haines TP. Investigation of the effectiveness of the “Girls on the Go!” program for building self-esteem in young women: trial protocol. SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1):683.

Turner J, Kelly B, Clarke D, Yates P, Aranda S, Jolley D, et al. A randomised trial of a psychosocial intervention for cancer patients integrated into routine care: the PROMPT study (promoting optimal outcomes in mood through tailored psychosocial therapies). BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):48.

Van de Steeg L, Langelaan M, Ijkema R, Wagner C. The effect of a complementary e-learning course on implementation of a quality improvement project regarding care for elderly patients: a stepped wedge trial. Implement Sci. 2012;7:13.

van Holland BJ, de Boer MR, Brouwer S, Soer R, Reneman MF. Sustained employability of workers in a production environment: design of a stepped wedge trial to evaluate effectiveness and cost-benefit of the POSE program. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1003.

Craine N. Cluster randomised controlled trial of dried blood spot testing in UK prisons. 2011. http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN05628482.

Everingham K. Enhanced Peri-Operative Care for High-risk patients (EPOCH) Trial: A stepped wedge cluster randomised trial of a quality improvement intervention for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. 2014. http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN80682973.

Grande G. A randomised trial to evaluate the impact of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) intervention in hospice home care. 2012. http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN75541926.

Koeberlein-Neu J. Prospective, cluster-randomized, controlled trial of effectiveness and costs of a cross-professional and cross-organisational medication therapy management in multimorbid patients with polypharmacy. 2013. http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN41595373.

Viikari-Juntura E. Efficacy of temporary work modifications on disability related to musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms: a non-randomised controlled trial. 2013. ISRCTN74743666.

Williams A. The effect of work-based mentoring of physiotherapists on patient outcome. 2012. http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN79599220.

Arnup SJ, Forbes AB, Kahan BC, Morgan KE, McDonald S, McKenzie JE. The use of the cluster randomized crossover design in clinical trials: protocol for a systematic. Syst Rev. 2014;3:86.

Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):S112–8.

Beard E, Lorencatto F, Gardner B, Michie S, West R, Owen L, et al. The specification of cost-effective behaviour change interventions. PloS One. http://publications.nice.org.uk/behaviour-change-individual-approaches-ph49/about-this-guidance.

Prost A, Binik A, Abubakar I, Roy A, de Allegri M, Mouchoux C, et al. Uncertainty on a background of optimism: logistic, ethical and political dimensions of stepped wedge designs. Trials.

Acknowledgements

EB has received unrestricted research funding from Pfizer for the Smoking Toolkit Study (www.smokinginegland.info). EB’s post is funded by Cancer Research UK and the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR). The SPHR is a partnership between the Universities of Sheffield; Bristol; Cambridge; Exeter; University College London; The London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; the LiLaC collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool and Lancaster and Fuse; and The Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, a collaboration between Newcastle, Durham, Northumbria, Sunderland and Teesside Universities.

JL was supported by funding from both the African Health Initiative of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (grant number: 2009060) for the Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessment stepped wedge trial and from Terre des Hommes for the Integrated e-Diagnosis Assessment stepped wedge trial. D Osrin is funded by The Wellcome Trust (grant number: 091561/Z/10/Z). The views are those of the authors(s) and not necessarily those of their funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

Audrey Prost is an associate editor of Trials. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AP conducted the literature search and screened all retrieved articles, abstracts and registration forms to check their eligibility for inclusion into the review. EB, JJL, AJC, CD, DO, GB, JAT, KLF, RZO, SO, JH and AP all extracted data from the retrieved articles using a standardized data extraction form. EB and JL then collated these forms and synthesized their results, liaising with other co-authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Contributions from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine authors are part of their work for the Centre for Evaluation, which aims to improve the design and conduct of public health evaluations through the development, application and dissemination of rigorous methods, and to facilitate the use of robust evidence to inform policy and practice decisions.

Emma Beard and James J. Lewis contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Data extraction form. (DOCX 22 kb)

Additional file 2:

Further characteristics of studies that adopted a stepped wedge randomised controlled trial design included in the review. (DOCX 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Beard, E., Lewis, J.J., Copas, A. et al. Stepped wedge randomised controlled trials: systematic review of studies published between 2010 and 2014. Trials 16, 353 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0839-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0839-2