Abstract

Background

Body Image is a major factor affecting health in a range of age groups, but has particular significance for adolescents. The aim of this research is to evaluate the efficacy of the “Girls on the Go!” program delivered outside of the school environment by health professionals to girls at risk of developing poor self-esteem on the outcomes of self-esteem, impairment induced by eating disorders, body satisfaction, self-efficacy, and dieting behaviour.

Method

A stepped wedge, cluster randomised controlled trial that was conducted in two phases on the basis of student population (Study 1 = secondary school age participants; Study 2 = primary school age participants). The waiting list for the “Girls on the Go!” program was used to generate the control periods. A total of 12 schools that requested the program were separated into study 1 or 2 on the basis of student population (Study 1 = secondary, Study 2 = primary). Schools were matched on the basis of number of students and were allocated to receiving the intervention immediately or having a waiting list period. Study 1 had one waiting list period of one school term, creating two steps in the stepped-wedge design (i.e. 3 schools were provided with “Girls on the Go!” each term over 2 terms). Study 2 had two waiting list periods of one and two school terms, creating three steps in the stepped-wedge design (i.e. 2 schools were provided with “Girls on the Go!” each term over 3 terms). Primary outcome measures were self-esteem and impairment inducted by eating disorders.

Discussion

There is a lack of preventative interventions currently available that address low self-esteem, low self-efficacy and body dissatisfaction in young women. This project will be the first group-based, professional-led, targeted program conducted outside the school environment amongst school age young women to be evaluated via a randomised control trial. These findings will indicate if the “Girls on the Go!” program may be successfully used and applied in a culturally diverse environment and with young women of all shapes and sizes.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Body image is the “mental picture” we form of our physical body and encompasses how we feel and think about our physical appearance (Bak-Sosnowska, 2008). Poor body image is common amongst both young men and women, but particularly so amongst young women (Paxton, 2000). Self-esteem is the overall evaluation of our worth, including how we like, respect, and accept ourselves (Mann et al., 2004). Another related self-concept, self-efficacy refers to the confidence we place in ourselves that we possess the ability and skills necessary to exercise control over our daily lives (Bandura, 1986). Due to society’s strong emphasis on appearance, many young people are confused about what self-esteem is and many tend to measure and value their self-worth by their shape, weight, appearance and material assets (O’Dea, 2004; Mann et al., 2004).

Positive relationships have been identified between poor body image and low self-esteem and health problems such as eating disorders (Chisuwa and O’Dea, 2010; Ata, 2003; Breines et al., 2008; O’Dea and Abraham, 2000; Paxton et al., 2006; Stice, 2002; Graber et al., 1994), depression and other mental health issues (Ambresin et al., 2012), obesity (Bak-Sosnowska, 2008), and being physically inactive (Huang et al., 2007). Also, poor body image has been associated with unhealthy weight loss practices such as engaging in extreme dieting behaviours like purging, and also binge eating (Heinicke et al., 2007; Paxton, 2000; Paxton, 1993). Links have been reported between weight loss practices and further weight gain (Stice et al., 1999) and this vicious cycle is believed to contribute to the child obesity epidemic (O’Dea, 2004). Some recent research now supports the notion that weight loss is only achieved short-term and food restriction leads to more weight gain, poorer self-esteem, eating disorders and overall poor health outcomes (Bacon and Aphramor, 2011; Bacon et al., 2005; Stice et al., 1999). Thus, the relationships between self-esteem, body image and dietary behaviours are complex and multi-faced. Indeed previous authors have described the effects of poor body image on emotional well-being and self-esteem as a ‘ripple effect’ that impacts on health (Healey, 2003, p.5).

Health education programs which enhance protective self-concepts such as self-esteem, self-efficacy are needed, in particular for young women. It is possible that incorporating health promoting activities within intervention programs designed to build self-esteem can be critical in addressing these inter-related problems as high self-esteem has been found to be a protective factor against body dissatisfaction and disordered eating (McVey et al., 2003, 2002; Wade et al., 2003; Button et al., 1996; O’Dea and Abraham, 2000; Smolak, 2009; O’Dea, 2004; Albee, 1996; Bayer, 1984; Thompson and Smolak, 2001; Shisslak et al., 2001). An approach focussed on addressing low self-esteem has been used by previous programs that aimed to improve body image and reduce eating problems amongst young children and adolescents (Steese et al., 2006; O’Dea, 2000, 2004; Steiner-Adair et al., 2002; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2000; Wade et al., 2003; McVey et al., 2004; O’Dea and Abraham, 2000; McVey, 2002; Richardson et al., 2009; Phelps et al., 2000; Kater et al., 2002; Smolak and Levine, 2001). These programs have generated promising though mixed results in improving a range of health amongst young women. Programs that promote improved self-esteem, self-efficacy and body image, reduced the thin idealisation while mitigating risk factors for eating disorders achieved short term effects (O’Dea, 2004; Steese et al., 2006; O’Dea and Abraham, 2000), though some similar programs did not demonstrate sustained benefits in the long term (McVey et al., 2004; Stewart et al., 2001), and others did not demonstrate any desired benefits (Wade et al., 2003; Paxton, 1993).

Programs designed to improve self-esteem, self-efficacy and body satisfaction, among young women can be categorised in many ways. This includes categorising according to the target population (e.g. Universal versus targeted program delivery), the setting of delivery (e.g. within or outside the school/classroom setting vs. community setting), whether the program is a group or individual (counselling) program, and the facilitation method of the program (health professional, peer or teacher led) (Stice and Shaw, 2004; Paxton, 2002, 2011; Levine and Smolak, 2009). There are potential advantages and disadvantages of each of these delivery methods. Delivering eating disorder prevention programs within the school environment allows large numbers of students to be readily provided with the program. However, previous research has generated mixed results as to whether programs delivered by trained peer leaders and teachers in the school environment produce positive outcomes (Becker et al., 2006; Marchand et al., 2011; Stice et al., 2009) as compared to negative outcomes (Carter et al., 1997; O’Dea, 2002, 2000b). One delivery issue that may be an important factor here is whether programs have been delivered to entire school populations or to selected sub-groups of students who are identified as being at higher-risk for developing poor self-esteem and other related negative outcomes. Delivery to only those at high risk may be a more cost-effective approach as resources are not being wasted on those who do not need them, while delivery of programs outside of the school environment permit privacy and allow students to be taken outside the setting which may be contributing to these problems. Further to this, programs led by peers or teachers may not facilitate open and honest discourse due to pre-existing relationships with the participants. Several meta-analyses (Stice and Shaw, 2004; Stice et al., 2007; Cororve Fingeret et al., 2006) have reported that for those at ‘high risk’ end of the spectrum interventions provided by trained professionals rather than teachers were more effective in obtaining long lasting and positive outcomes.

Much of the previous research that has been conducted has not targeted girls at higher risk of developing poor self-esteem and related health outcomes amongst those under the age of 15, and it is less certain whether programs such as those previously investigated are beneficial when delivered to these younger women. This research aims to determine the efficacy of a community-based, health professional-run program to improve self-esteem and related health outcomes amongst girls who have been identified as being at risk of developing eating disorders, body dissatisfaction, or extreme dieting behaviour. The hypothesis to be tested is that participants exposed to this program will experience improvement in self-esteem, mental health self-efficacy, physical health self-efficacy, body satisfaction, dieting behaviour and they will experience less impairment induced by eating disorders relative to those exposed to the waiting-list control condition. Age is a salient factor for prevention interventions designed to minimise future ‘risk’, for example early intervention and skill training are recommended for resilience building (Gillham and Reivich, 2010) (Zolkoski and Bullock, 2012). Therefore, this larger project incorporated two separate studies. Study one investigates the efficacy of the program with high school age participants. Study two investigates the efficacy of the program with primary school age participants.

Design

This study comprised a stepped wedge, cluster randomised controlled trial that was conducted in two phases on the basis of student population (Study 1 = secondary school age participants; Study 2 = primary school age participants). Stepped wedge designs are similar to cross-over trials, however only involve uni-directional cross-over resulting in all participants receiving the intervention by the conclusion of the trial. The waiting list for the “Girls on the Go!” program was used to generate the control period. The intervention program was designed to be delivered to a group of participants from the same school at the same time, thus randomising students in clusters (school) was seen as an appropriate unit of randomisation.

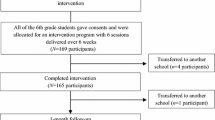

A total of 12 schools that requested the program were separated into Study 1 or 2. Within each study, schools were matched on the basis of number of students (into triplets for Study 1 and pairs for Study 2) and then randomly allocated (computer generated sequence developed by investigator blinded to school identity) to receiving the intervention immediately or having a waiting list period. Study 1 had one waiting list period of one school term, creating two steps in the stepped-wedge design (i.e. 3 schools were provided with “Girls on the Go!” each term over 2 terms–see Figure 1). Study 2 had two waiting list periods of one and two school terms, creating three steps in the stepped-wedge design (i.e. 2 schools were provided with “Girls on the Go!” each term over 3 terms–see Figure 2).

Participants and setting

Participants in this study were either high school or primary school students who were referred to the Greater Dandenong Community Health Centre to receive the intervention program. The intervention was a program being run prior to the conduct of this trial and schools in the City of Greater Dandenong municipality had been routinely referring students to this program for the previous 8 years. Each school group consisted of between 8–12 participants.

Inclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria of young women to be referred to the program and also to be included in the study were: poor or negative body image, low self-esteem, inactivity in sports and exercise, poor diet, or being overweight or underweight. Participants were between 10 and 17 years of age. These students needed to be identified and referred by their school welfare officer or teacher.

Local contextual considerations

The City of Greater Dandenong is the most culturally diverse locality in Victoria, Australia, with residents from 156 different birthplaces, over half (56%) of its population born overseas, and 51% from nations where English is not the main spoken language. An influx of approximately 2300 newly arrived settlers per year since 2006 has sustained this diversity. The City of Greater Dandenong has also been described as one of the lowest socio-economic indexes for (SIEFA) Melbourne (SIEFA indices allow ranking of regions/areas by providing a method of identifying the level of social and economic well-being in each region) (ABS, 2011).

Intervention

The community-based, health professional led program that formed the intervention for this research is called the “Girls on the Go!” program.

“Girls on the Go!” program development

A Youth Community Health Team in Melbourne, Australia, developed the “Girls on the Go!” in response to an identified need and demand by local schools and communities for a program designed to address body dissatisfaction and promote healthier lifestyles. The program developers were unable to model elements of this program on what was known to be successful in 2001 due to a paucity of evidence from experimental studies investigating the efficacy of programs to improve self-esteem in young women. Indeed the concept of using programs to enhance self-esteem in order to minimise disordered eating was only proposed in the late 1990s (O’Dea and Abraham, 2000).

Following a successful pilot program, a forum was held which included local schools and youth agencies which resulted in further promotion of the existence of the program through word of mouth. It was intended “Girls on the Go!” target young women who have been identified to be at high risk of a variety of eating and body image difficulties, poor self-esteem, low self-efficacy, negative self-image and physical inactivity at an early stage so they do not develop a serious mental illness e.g. anorexia/bulimia nervosa, or physical illness e.g. diabetes, heart conditions, later in life.

The program was initially developed by a multidisciplinary team of health practitioners including a Social Worker, Sport and Recreational Worker, and a Community Health Nurse. These workers had specific skills pertaining to their discipline and their area of expertise was used to contribute to separate components of the program. For example, the Social Worker contributed counselling specific skills to the program in general but also contributed more specific information to the session “A healthy mind” and “Body Image and Self Esteem” as well as providing the initial link with the young person as someone they know and could contact later should they require additional one on one support. The Sports and Recreational worker provided their expertise into designing the physical exercise components of the program as well as linking into their networks and contacts from the Sports and Recreational Industry. Previously these workers had been independently running programs to address health and wellbeing issues such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, body image, mental health, stress and relaxation, healthy lifestyles, healthy eating and being physically active. However, they sought to integrate a combined program of activities that could be conducted in a group context.

Theoretical approach underpinning the development of “Girls on the Go!”

The initial stages of the “Girls on the Go!” program development were driven more from practical experience. However the founders of the program came from various disciplines (i.e. sport and recreational work, social work, youth work, and nursing) that can be placed within the allied health spectrum and the program was set up within a primary health setting. Hence similarities existed in their approach to working with young people. The program was developed therefore, with an overarching theme of engaging young women in a holistic manner within an early intervention bio/psycho/social health model (Engel, 1977).

The bio-psycho-social model of health is a theoretical model used for considering individual and population health and wellbeing. It operates under the presumption that improved health and well-being may be achieved by targeting the determinants of health including social and environmental as well as the biological and medical factors. Working within the social model of health is advantageous because it permits not only individuals but entire communities to define health according to their understanding of it (Keleher and Marshall, 2002). Therefore, it empowers them to identify important factors that influence their own health depending on their specific context. The social model of health proposes that physical, mental and social health is interlinked and play an equal role in wellbeing. This is especially relevant when considering the multiple influences and risk factors of disordered eating. The individuals’ self-concept is greatly impacted by each of these determinants and the social model of health gives a holistic and well balanced framework to develop an effective program.

Program description–content

“Girls of the Go!” provides a structured, community-based, half-day, 10 week health promotion program for a group of up to 10 young women that uses self-esteem enhancement, to improve body satisfaction, self-efficacy, and promote healthy lifestyles including healthy eating and reduce dieting behaviour and promote positive attitudes towards sport and exercise. The intervention encourages information sharing and providing support to one another which leads to strong relationships forming amongst members of the group. Participants share their similar experiences and this draws them closer to one another.

Positive mental and physical health is promoted via education about healthy lifestyle choices, building self-esteem and self-efficacy, improving body dissatisfaction via media literacy, participating in fun activities and developing community linkages for participants. Youth Workers deliver the program with other health professional such as dieticians and physiotherapists supporting the program as needed.

Active participant involvement in planning program activities is incorporated to empower participants to make decisions about their own health to make the continuation of positive practices more likely at the completion of the group. Participants engage in activities and discussion designed to address a particular topic. Elements of the program and duration may be modified according to the needs of the target group, skills, experience, equipment and facility availability. The program was initially developed for a community health setting but has since been expanded to youth agencies, neighbourhood houses, local hospital as well as main stream and non-mainstream schools. To ensure fidelity of the program delivered, all facilitators must undergo formal training and also observe one full program before being able to lead a program on their own. The program has always been delivered from a community health centre setting and outside the school classroom environment.

The “Girls on the Go!” program is delivered over a ten week period with a total of 26 contact hours over the life of the program consisting of interactive discussion and activities (See Table 1).

Pilot of the “Girls on the Go!” intervention

A retrospective program review of the data collected from participants between 2001 and 2009 was conducted. Ethical approval was received by the Southern Health’s Research Directorate (Research Project number: 09252Q, HREC09252). Questions examining self-esteem, self-efficacy (responses captured using 5 point visual analogue scale), and satisfaction with body image (responses captured using 4 point visual analogue scale) were compared between pre and post program assessments using ordered logit regression analysis with clustering by participant to account for dependency between pre and post assessments within participant.

Ordered logit regression calculates the increase or decrease in odds of moving up one level in the ordinal dependent variable associated with a one unit change in the independent variable. The location of the interquartile range for each of these items was located higher in the scale range in the post program assessment compared to the pre-program assessment indicating that the program was beneficial to these outcomes. The odds (95% CI), p-value of moving up one level for self-esteem with completing the program was 4.89 (3.47, 6.88), p < 0.001, for self-efficacy was 4.65 (3.42, 6.32), p < 0.001, and for satisfaction with body image was 3.68 (2.66, 5.11), p < 0.001. Despite these promising results, the limitations of the pre-post intervention research design dictated that further work using randomised trial methodology was necessary to establish the efficacy of the “Girls on the Go!” program.

Primary outcome measures

The Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965) was used to assess feelings of self-worth. This scale consists of ten items, each item is rated on a 4-point scale where 4 = “strongly agree”, 3 = “agree”, 2 = “disagree” and 1 = “strongly disagree”. An example of an item includes “I take a positive attitude towards myself”. Some items are negatively worded for instance “I certainly feel useless at times” and these have been reversed scored in final scoring process. Items were added up with possible scores for the scale ranged from 10 to 40 were higher scores are indicative of greater self-esteem. The Rosenberg self-esteem scale has been widely used and has been reported to have great internal consistency (Chronbach’s α = .88) and validity scores (Rosenberg, 1965; Rosenberg and Simmons, 1971; Simmons et al., 1973).

The eating disorders assessment [Clinical Interview Assessment, (CIA)] developed by Bohn and colleagues (Bohn et al., 2008) (16-items scale) was used to assess psycho-social impairment induced by eating disorders. Participants were asked to indicate over the past month, to what extent have their eating habits, exercising, or feelings about your eating, shape or weigh caused them impairment in three areas including cognitive “made you feel upset”, personal “Interfered with you doing things you used to enjoy” and social “made it difficult to eat out with others”. Each item is scored on a 4-point response format 0 = “not at all”, 1 = “slightly”, 2 = “moderately” and 3 = “a lot”. The scale scores ranged from 0 to 48, higher scores are indicative of greater impairment and eating disorders. This scale has demonstrated high internal consistency and test-retest reliability and good validity (Bohn et al., 2008).

Secondary outcome measures

Body satisfaction was measured by the body esteem scale developed by Katz-Mendelson and White (1982) which was found to be a reliable instrument with children as young as 7 years old. The 24 items in this scale encompass how a person values their appearance and body. There are equal numbers of positive and negative items and participants are asked to agree or disagree with each item. An example of a positive item is “I’m proud of my body” and a negative item is “I wish I was thinner”. The scale is scored by counting the number of responses indicating positive body esteem (maximum score is 24). A high score on the scale reflects higher body satisfaction.

Body Dissatisfaction was measured with a subscale of the Eating Disorders Inventory (Garner et al., 1983). The scale contained 9 items designed to measure dissatisfaction with specific body parts. Examples of items include “I think my hips are too big” and “I think that my stomach is just the right size”. Responses were rated on a 6 point scale where 1 = never and 6 = always. Scores ranged from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating higher dissatisfaction.

Self-efficacy was measured by a self-efficacy scale designed to assess individuals’ sense of competence in particular areas. We used Froman and Owen’s (1991) health self-efficacy measure designed for use with high school students. The 43 item scale has two subscales, physical health self-efficacy and mental health self-efficacy. Participants are asked to indicate their degree of confidence where 1 = “a little” and 5 = “a lot” in their ability to complete a number of tasks. An example of task from physical health self-efficacy scale include “treating a fever” and mental health self-efficacy scale “maintaining a positive attitude towards school”. This scale was slightly refined to suit the current study’s participants. For example some items such as “avoiding illegal drugs”, were removed to make the scale appropriate for younger age participants. The final scale used had 37 items, scores for the scale ranged from 37 to 185 were higher scores are indicative of greater physical health or mental health self-efficacy.

Dieting behavior was assessed by the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire for Children (van Strien and Oosterveld, 2008) comprised of three subscales including: restrained eating, emotional eating and external eating. The scale is designed to assess the degree of concern a participant has about dieting and restricting the amount of food they may otherwise eat. There are a total of 20 items. Participants are asked to circle either yes, no or sometimes to a statements such as restrained eating subscale: “If you have eaten too much do you eat less than usual the next day?”; emotional eating subscale, “if you feel depressed do you get a desire for food?” and external eating subscale “do you feel like eating whenever you see or smell food?”. Each item is scored on a 3-point response format no (0), sometimes (1), yes (2). The scores are then summed up and higher scores represent higher dieting behaviour. Scores range from 0–48. This scale has demonstrated excellent reliability, Cronbach’s α = 0.80 restrained eating, Cronbach’s α = 0.81 emotional eating, and Cronbach’s α = 0.74 external eating, (van Strien et al., 1986; van Strien and Oosterveld, 2008) and has been widely used (Higgins and Gray, 1998; Carter et al., 1997; Higgins and Altman, 2008).

Procedure

Ethics and trial registration

The randomised control trial was prospectively registered with the Australian and New Zealand Control Trial Registry (ACTR 12610000513011). The trial was conducted in two phases that comprised Study 1 and Study 2.

Study 1 was prospectively registered with the Australian and New Zealand Control Trial Registry (ACTRN12610000513011). We then received notification of further funding to conduct this and Study 2. We submitted an amendment to our ethics application (ethics approval 10119B) to conduct Study 2 with the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee as the population of Study 2 and study design only varied slightly from Study 1 (Study 1 involved high school students and had a stepped wedge design of 3 schools being provided with the intervention per term, while Study 2 involved primary school students and had a stepped wedge design of 2 schools being provided with the intervention per term). We then amended the Australian and New Zealand Control Trial Registry so that the sample size listed on the registry was increased from 60 to 120 participants.

Study 1

High schools that contacted the Greater Dandenong Community Health Service in 2010 to receive the “Girls on the Go!” program that year were notified of the research and that their school’s placement on the waiting list that year would be determined at random. School welfare officers and teachers forwarded to the Greater Dandenong Community Health Service the list of student names who they determined met the study and program inclusion criteria. An investigator (LT) gained consent from participant’s parents (with assent from the participant) to participate in the research from all referred students. This investigator administered the data collection surveys at baseline and follow-up assessments at the time points indicated (Figures 1 and 2). The program was provided to schools in the order determined by the matched, random allocation sequence.

Study 2

The same recruitment and data collection approaches were used for study 2, though with recruitment derived from primary schools, and the addition of one further follow-up assessment.

Analyses

The effect of being exposed to the “Girls on the Go!” program will be examined using a linear mixed model analysis approach, suitable for analysing longitudinal data where there is likelihood of missing data or loss to follow-up. The model that will be constructed to conduct this analysis will require construction of an independent variable, labelled “Girls on the Go”. This variable will be coded a 0 for observations where the group had not yet been exposed to the “Girls on the Go!” intervention (e.g. In study 1; at baseline for all schools and also at the first follow-up assessment but only for schools in the “Waiting List” period–see Figure 1), and 1 for observations where the participants had already received the “Girls on the Go!” intervention (e.g. In study 1; at the first follow-up assessment for schools in the first “Girls on the Go” period and also for all schools at the second follow-up assessment). Raw summative outcome measurement scores will be used as the dependent variables.

The mixed model analysis will involve investigating the effect of the “Girls on the Go” variable on the dependent variable, adjusting for assessment number (to account for the effect of time). The “Girls on the Go” variable will be entered into the model as a fixed factor, while assessment, student and school will be entered as random factors. Assessment will be nested within student which will be nested within school which will create a 3-level model that takes into account the longitudinal, clustered nature of data collected in this study. Maximum likelihood methods of estimation will be employed to address issues of missing data under the assumption of Missing At Random.

To investigate whether the effect of the “Girls on the Go!” program was sustained, a “Girls on the Go” by assessment interaction effect will be added to the same analysis models. A significant interaction effect in these models will indicate whether any changes brought about at the initial post-“Girls on the Go!” follow-up assessment were sustained. We will also examine the data from the group that received the “Girls on the Go!” program first and compare student results between the first and subsequent post-intervention follow-up assessments in isolation using linear regression clustering data by individual student.

Power analysis

Analysis of data from the pilot study indicated that the effect of the “Girls on the Go!” program on participant self-esteem was very strong (ie. Change in outcome is 1.5 times the width of the standard deviation). Assuming 80% power, only 10 participants per group will be required in a standard randomised trial with randomisation of individual participants. This study will be a cluster randomised trial however to account for a variance inflation factor (design effect) of 3 (where average size per cluster is n =10, and the ICC is assumed to equal 0.33) then a total of 120 participants in both the primary (n = 60) and secondary (n = 60) schools will be required.

Discussion

Low self-esteem and its associate health consequences such as body dissatisfaction and eating disorders are important societal, cultural, familial and individual matters. They demand urgent attention, greater resources and evidenced based approaches to both assist young people, and girls in particular with low self-esteem and body image concerns and to prevent others from its development. High self-esteem is known to be a protective factor against the development of body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating and therefore this project may have the potential to contribute to the field of prevention of disordered eating. “Girls on the Go!” was developed to deal with these particular issues. To our knowledge this is the first group-based, professional-led, targeted program conducted outside the school environment amongst school age young people with such culturally diverse backgrounds to be evaluated.

This research will enable clinicians to evaluate a new community preventative intervention and thus to apply research into clinical practice. Before the expansion of “Girls on the Go!” it should be subjected to evaluation to demonstrate that it does achieve its objectives. These findings will indicate if the “Girls on the Go!” program may be successfully used and applied in a culturally diverse community and with disadvantaged participants. The results of the two individual studies will allow for comparison of the intervention’s effect at various age groups (i.e. primary school vs secondary schools age young women). Furthermore, “Girls on the Go!” targets girls who have diverse body shapes and sizes and this control trial results will indicate if a holistic approach focused on self-esteem will lead to overall improved health and wellbeing. Therefore, these findings will support a relatively new paradigm shift where self-esteem enhancement and overall health and well-being are emphasized and used as a prevention strategy and it will potentially support the notion that improving self-esteem would lead to improved self-efficacy and body satisfaction in young women (O’Dea and Maloney, 2000; O’Dea, 2005, 2000b; Bacon and Aphramor, 2011).

Information collected by the present research, that documents the development of a preventative intervention originated from a health service delivery, and evaluation of these data, will contribute new information to the field of prevention of eating disorders and health promotion delivery.

References

ABS: Census of Population and Housing. Australia. Canberra: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA); 2011.

Albee GW: Revolutions and counterrevolutions in prevention. Am Psychol 1996, 51(11):1130-1133.

Ambresin A-E, Belanger RE, Chamay C, Berchtold A, Narring F: Body dissatisfaction on top of depressive mood among adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012, 25(1):19-22. 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.06.014

Ata G: Structural modeling analysis of prospective risk factors for eating disorder. Eat Behav 2003, 3(4):387-396. doi:10.1016/s1471-0153(02)00089-2 10.1016/S1471-0153(02)00089-2

Bacon L, Aphramor L: Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J 2011, 10(1):9. 10.1186/1475-2891-10-9

Bacon L, Stern J, Van Loan M, Keim N: Size acceptance and intuitive eating improve health for obese, female chronic dieters. J Am Diet Assoc 2005, 105: 929-936. 10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.011

Bak-Sosnowska M: Imaginary or real? The body image in obese people. In Life style and health research progress. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Biomedical Books; 2008:209-250.

Bandura A: The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 1986, 4(3):359-373. doi:10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Bayer AE: Eating out of control: anorexia and bulimia in adolescents. Child Today 1984, 13(6):7.

Becker CB, Smith LM, Ciao AC: Peer-facilitated eating disorder prevention: a randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive dissonance and media advocacy. J Couns Psychol 2006, 53(4):550-555.

Bohn K, Doll HA, Cooper Z, O’Connor M, Palmer RL, Fairburn CG: The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behav Res Ther 2008, 46(10):1105-1110. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.012 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.012

Breines JG, Crocker J, Garcia JA: Self-objectification and well-being in women’s daily lives. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2008, 34(5):583-598. doi:10.1177/0146167207313727 10.1177/0146167207313727

Button EJ, SonugaBarke EJS, Davies J, Thompson M: A prospective study of self-esteem in the prediction of eating problems in adolescent schoolgirls: questionnaire findings. Br J Clin Psychol 1996, 35: 193-203. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01176.x

Carter JC, Stewart DA, Dunn VJ, Fairburn CG: Primary prevention of eating disorders: might it do more harm than good? Int J Eat Disord 1997, 22(2):167-172. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199709)22:2<167::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-d 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199709)22:2<167::AID-EAT8>3.0.CO;2-D

Chisuwa N, O’Dea JA: Body image and eating disorders amongst Japanese adolescents. A review of the literature. Appetite 2010, 54(1):5-15. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.008 10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.008

Cororve Fingeret M, Warren CS, Cepeda-Benito A, Gleaves DH: Eating disorder prevention research: a meta-analysis. Eat Disord 2006, 14(3):191-213. doi:10.1080/10640260600638899 10.1080/10640260600638899

Engel G: The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196(4286):129-136. doi:10.1126/science.847460 10.1126/science.847460

Froman RD, Owen SV: High school students’ perceived self-efficacy in physical and mental health. J Adolesc Res 1991, 6(2):181-196. doi:10.1177/074355489162003 10.1177/074355489162003

Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J: Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983, 2(2):15-34. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:2<15::AID-EAT2260020203>3.0.CO;2-6 10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:2<15::AID-EAT2260020203>3.0.CO;2-6

Gillham J, Reivich K: Building resilience in youth: the Penn Resiliency Program. Communique 2010., 38:

Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff RL, Warren MP: Prediction of eating problems: an 8-year study of adolescent girls. Dev Psychol 1994, 30(6):823-834.

Healey J: Healthy body image. Rozelle: N.S.W: Spinney Press; 2003.

Heinicke BE, Paxton SJ, McLean SA, Wertheim EH: Internet-delivered targeted group intervention for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2007, 35(3):379-391. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9097-9 10.1007/s10802-006-9097-9

Higgins JPT, Altman DG: Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008:187-241. doi:10.1002/9780470712184.ch8

Higgins L, Gray W: Changing the body image concern and eating behaviour of chronic dieters: the effects of a psychoeducational intervention. Psychol Health 1998, 13: 1045-1060. 10.1080/08870449808407449

Huang JS, Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Calfas K, Patrick K, Huang JS, Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Calfas K, Patrick K: Body image and self-esteem among adolescents undergoing an intervention targeting dietary and physical activity behaviors. J Adolesc Health 2007, 40(3):245-251. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.026

Kater KJ, Rohwer J, Londre K: Evaluation of an upper elementary school program to prevent body image, eating, and weight concerns. J Sch Health 2002, 72(5):199-204. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06546.x

Keleher H, Marshall B: A Framework for Strengthening Health Promotion in Community Health. Melbourne: Deakin University; 2002.

Levine MP, Smolak L: Recent developments and promising directions in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating in children and adolescents. In Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment. 2nd edition. Edited by: Smolak L, Thompson JK. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009:215-238. xiii, 389 pp

Mann M, Hosman CMH, Schaalma HP, de Vries NK: Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Educ Res 2004, 19(4):357-372. doi:10.1093/her/cyg041 10.1093/her/cyg041

Marchand E, Stice E, Rohde P, Becker CB: Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behav Res Ther 2011, 49(1):32-41. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008

McVey GL: A program to promote positive body image. J Early Adolesc 2002, 22(1):96. 10.1177/0272431602022001005

McVey GL, Pepler D, Davis R, Flett GL, Abdolell M: Risk and protective factors associated with disordered eating during early adolescence. J Early Adolesc 2002, 22(1):75-95. doi:10.1177/0272431602022001004 10.1177/0272431602022001004

McVey GL, Lieberman M, Voorberg N, Wardrope D, Blackmore E: School-based peer support groups: a new approach to the prevention of disordered eating. Eat Disord 2003, 11(3):169. 10.1080/10640260390218297

McVey GL, Davis R, Tweed S, Shaw BF: Evaluation of a school-based program designed to improve body image satisfaction, global self-esteem, and eating attitudes and behaviors: a replication study. Int J Eat Disord 2004, 36(1):1-11. doi:10.1002/eat.20006 10.1002/eat.20006

Mendelson BK, White DR: Relation between body-esteem and self-esteem of obese and normal children. Percept Mot Skills 1982, 54(3):899-905. 10.2466/pms.1982.54.3.899

Neumark-Sztainer D, Sherwood NE, Coller T, Hannan PJ: Primary prevention of disordered eating among preadolescent girls: feasibility and short-term effect of a community-based intervention. J Am Diet Assoc 2000, 100(12):1466-1473. doi:10.1016/s0002-8223(00)00410-7 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00410-7

O’Dea J: Preventing eating and body image problems in children and adolescents using the health promoting schools framework. J Sch Health 2000, 70(1):18-21. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06441.x

O’Dea J: School-based interventions to prevent eating problems: first do no harm. Eat Disord 2000, 8(2):123-130. doi:10.1080/10640260008251219 10.1080/10640260008251219

O’Dea J: Can body image education programs be harmful to adolescent females? Eat Disord 2002, 10(1):1-13. 10.1002/erv.453

O’Dea JA: Evidence for a self-esteem approach in the prevention of body image and eating problems among children and adolescents. Eat Disord 2004, 12(3):225-239. doi:10.1080/10640260490481438 10.1080/10640260490481438

O’Dea JA: Prevention of child obesity: ‘first, do no harm’. Health Educ Res 2005, 20(2):259-265. doi:10.1093/her/cyg116

O’Dea JA, Abraham S: Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: a new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. Int J Eat Disord 2000, 28(1):43-57. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200007)28:1<43::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-d 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200007)28:1<43::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-D

O’Dea J, Maloney D: Preventing eating and body image problems in children and adolescents using the health promoting schools framework. J Sch Health 2000, 70(1):18. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06441.x

Paxton SJ: A prevention program for disturbed eating and body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: a 1 year follow-up. Health Educ Res 1993, 8(1):43-51. doi:10.1093/her/8.1.43 10.1093/her/8.1.43

Paxton S: Body image dissatisfaction, extreme weight loss behaviours: suitable targets for public health concerns? Health Promot J Austr 2000, 10(1):15-19.

Paxton S: Research Review of Body Image Programs. An overview of Body Image Dissatisfaction Prevention Interventions. Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Human Services; 2002.

Paxton S: Psychological prevention and intervention strategies for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: [Paper in special issue: The Psychology of Eating Disturbances]. In-Psych 2011, 33(4):10-12.

Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME: Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2006, 35(4):539-549. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5

Phelps L, Sapia J, Nathanson D, Nelson L: An empirically supported eating disorder prevention program. Psychol Schools 2000, 37(5):443-452. doi:10.1002/1520-6807(200009)37:5<443::aid-pits4>3.0.co;2-8 10.1002/1520-6807(200009)37:5<443::AID-PITS4>3.0.CO;2-8

Richardson SM, Paxton SJ, Thomson JS: Is BodyThink an efficacious body image and self-esteem program? A controlled evaluation with adolescents. Body Image 2009, 6(2):75-82. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.11.001 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.11.001

Rosenberg M: Society and the adolescent self-image. Princenton NJ: University Press; 1965.

Rosenberg M, Simmons RG: Black and White Self-Esteem: The Urban School Child. The Arnold and Caroline Rose Monograph Series in Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1971.

Shisslak CM, Crago M, Shisslak CM, Crago M: Risk and protective factors in the development of eating disorders. American Psychological Association 2001. doi:10.1037/10404-004

Simmons RG, Rosenberg F, Rosenberg M: Disturbance in the self-image at adolescence. Am Sociol Rev 1973, 38(5):553-568. 10.2307/2094407

Smolak L: Risk factors in the development of body image, eating problems, and obesity. In Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment. 2nd edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009:135-155. doi:10.1037/11860-007

Smolak L, Levine MP: A two-year follow-up of a primary prevention program for negative body image and unhealthy weight regulation. Eat Behav 2001, 9(4):313-325.

Steese S, Dollette M, Phillips W, Hossfeld E, Matthews G, Taormina G: Understanding girls’ circle as an intervention on perceived social support, body image, self-efficacy, locus of control, and self-esteem. Adolescence 2006, 41(161):55-74.

Steiner-Adair C, Sjostrom L, Franko DL, Pai S, Tucker R, Becker AE, Herzog DB: Primary prevention of risk factors for eating disorders in adolescent girls: learning from practice. Int J Eat Disord 2002, 32(4):401-411. doi:10.1002/eat.10089 10.1002/eat.10089

Stewart DA, Carter JC, Drinkwater J, Hainsworth J, Fairburn CG: Modification of eating attitudes and behavior in adolescent girls: a controlled study. Int J Eat Disord 2001, 29(2):107-118. doi:10.1002/1098-108x(200103)29:2<107::aid-eat1000>3.0.co;2-1 10.1002/1098-108X(200103)29:2<107::AID-EAT1000>3.0.CO;2-1

Stice E: Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 2002, 128(5):825-848. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.128.5.825

Stice E, Shaw H: Eating disorder prevention programs: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 2004, 130(2):206-227. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.206

Stice E, Cameron R, Killen J, Hayward C, Taylor C: Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999, 67: 967-974.

Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN: A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: encouraging findings. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2007, 3(1):207-231. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091447 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091447

Stice E, Rohde P, Gau J, Shaw H: An effectiveness trial of a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for high-risk adolescent girls. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009, 77(5):825-834.

Thompson JK, Smolak L: Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment. US: Taylor & Francis; 2001.

van Strien T, Oosterveld P: The children’s DEBQ for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating in 7- to 12-year-old children. Int J Eat Disord 2008, 41(1):72-81. doi:10.1002/eat.20424 10.1002/eat.20424

van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB: The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord 1986, 5(2):295-315. doi:10.1002/1098-108x(198602)5:2<295::aid-eat2260050209>3.0.co;2-t 10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T

Wade TD, Davidson S, O’Dea JA: A preliminary controlled evaluation of a school-based media literacy program and self-esteem program for reducing eating disorder risk factors. Int J Eat Disord 2003, 33(4):371-383. doi:10.1002/eat.10136 10.1002/eat.10136

Zolkoski SM, Bullock LM: Resilience in children and youth: a review. Child Youth Serv Rev 2012, 34(12):2295-2303. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009

Acknowledgements

This study was mainly funded by the Butterfly Foundation via the Butterfly Research Institute and Identification and Early Intervention Collaborative grants.

The study was also partly funded by Monash Health (formerly Southern Health) via the Emerging Researcher Fellowship to LT and Greater Dandenong Community Health Services.

Special thanks to all the students participants in this research, school staff and clinical staff who assisted at various stages with this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

LT is one of the Monash Health staff members co-founder of the “Girls on the Go!” program, but she has no financial interest in the program. HT and TH declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LT is the co-founder of the “Girls on the Go!” program and manual. She was involved in the delivery of the “Girls on the Go!” intervention to the participants, ethics application preparation, recruiting the participants, data collection, data entry, data cleaning, data analysing of the pilot and writing up the manuscript. LT is the recipient of the Southern Health Emerging Fellowship Grant. This author co-wrote with TH and HT the funding application grants for both the Emerging Researcher Fellowship and the Butterfly Grant that supported this project. HT has contributed insight into the use of appropriate scales to use to measure body image in children. HT has contributed to the ethics application and obtaining ethics clearance for the project. HT had input with the drafting of the manuscript. She initiated search for funding and contributed to the Butterfly grant preparation. TH was involved with the study design, research methodology, ethics application and ethics clearance for the project, registration of the clinical trial, data analysis, provided statistical expertise, interpreting the results of the pilot, drafting the manuscript and revising drafts. TH also co-wrote with LT and HT the funding application grant from both the Emerging Researcher Fellowship and the Butterfly Grant that supported this project. Both LT and TH took the lead into designing the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tirlea, L., Truby, H. & Haines, T.P. Investigation of the effectiveness of the “Girls on the Go!” program for building self-esteem in young women: trial protocol. SpringerPlus 2, 683 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-683

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-683