Abstract

Background/Objective

Death in intensive care units (ICUs) may increase bereaved family members’ risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, posttraumatic stress-related symptoms (hereafter as PTSD symptoms) and their precipitating factors were seldom examined among bereaved family members and primarily focused on associations between PTSD symptoms and patient/family characteristics. We aimed to investigate the course and predictors of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members of deceased ICU patients by focusing on modifiable quality indicators for end-of-life ICU care.

Method

In this longitudinal observational study, 319 family members of deceased ICU patients were consecutively recruited from medical ICUs from two Taiwanese medical centers. PTSD symptoms were assessed at 1, 3, 6, and 13 months post-loss using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R). Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in ICUs was assessed at 1 month post-loss. End-of-life care received in ICUs was documented over the patient’s ICU stay. Predictors for developing clinically significant PTSD symptoms (IES-R score ≥ 33) were identified by multivariate logistic regression with generalized estimating equation modeling.

Results

The prevalence of clinically significant PTSD symptoms decreased significantly over time (from 11.0% at 1 month to 1.6% at 13 months post-loss). Longer ICU stays (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval] = 1.036 [1.006, 1.066]), financial insufficiency (3.166 [1.159, 8.647]), and reported use of pain medications (3.408 [1.230, 9.441]) by family members were associated with a higher likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members during bereavement. Stronger perceived social support (0.937 [0.911, 0.965]) and having a Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order issued before the patient’s death (0.073 [0.011, 0.490]) were associated with a lower likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms. No significant association was observed for family members’ satisfaction with end-of-life care (0.988 [0.944, 1.034]) or decision-making in ICUs (0.980 [0.944, 1.018]).

Conclusions

The likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members decreased significantly over the first bereavement year and was lower when a DNR order was issued before death. Enhancing social support and facilitating a DNR order may reduce the trauma of ICU death of a beloved for family members at risk for developing clinically significant PTSD symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intensive care has grown substantially over the past decades worldwide [1,2,3] to be one of the most resource-intensive acute hospital services [4]. Heavy utilization of the intensive care unit (ICU) over the disease course contributes to high costs of health care [1] and raises concern over optimal use of ICU resources [5], especially for end-of-life (EOL) care, which has increased in the last decade [6]. Landmark studies highlighted the improving but still poor quality of EOL care in ICUs [7,8,9]. Thus, improving EOL-care quality in ICUs is essential [10] for improving the quality of death and dying [11], facilitating bereavement adjustment among family members [10], and counteracting unsustainable ICU care expenditures [10, 11].

Family members of ICU patients are an integral part of ICU care and a critical target for improving EOL-care quality in ICUs [12, 13]. The uncertain trajectory of critical illnesses, the frightening nature of aggressive life-prolonging treatments [14], and the beloved’s unexpected and eventual death are traumatic events for family members of ICU patients [15]. Therefore, family members are at increased risk for post-intensive care syndrome (PICS-F)—new or worsening impairments in physical, cognitive, or mental health status arising after a beloved’s critical illness and persisting beyond acute care hospitalization [16], including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [14]. PTSD takes a toll on physical [17, 18] and mental [17,18,19] health, personal relationship/social functioning [20] and poses a considerable economic burden for individuals, health care systems, and societies [21, 22]. These striking characteristics make PTSD a public mental health priority [19].

A better understanding of the modifiable risk factors for developing posttraumatic stress-related symptoms (hereafter as PTSD symptoms) may allow health care professionals to preemptively identify family members who are vulnerable to PTSD symptoms during bereavement and develop actionable high-quality, family-centered EOL care in ICUs. However, most studies [14] that examined potential predictors of PTSD symptoms among family members of ICU patients were done primarily on those of ICU survivors [9, 14, 23,24,25,26,27], while only a handful were done on those of deceased patients [7,8,9, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Furthermore, only a few of these studies found significant associations, and the majority of them focused on immutable family and patient characteristics [7, 9, 14, 23,24,25,26, 28, 29]. From the few [28, 29, 33] that examined process-based quality indicators of EOL care in ICUs, it was found that participation in early family meetings and presence at the time of patient’s death were associated with worse PTSD symptoms among family members [28], whereas withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (LSTs) had no association [29, 33]. The association between family’s perception/satisfaction of the quality of death in ICUs and PTSD was inconclusive [8, 9, 25, 26, 30].

Studies on PTSD among family members of ICU patients [7,8,9, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] also remain limited by methodological insufficiencies. First, most studies were cross-sectional [7,8,9, 23, 25, 27,28,29, 32], with PTSD symptoms measured across a wide range of time (1–9 months post-loss), which makes it difficult to compare prevalence of PTSD across studies and precludes the possibility of establishing temporal associations with predictors. Second, while most of the six longitudinal studies [24, 26, 30, 31, 33, 34] assessed PTSD symptoms at 3 [30, 31, 33, 34] and 6 [26, 30, 31, 33, 34] months post-loss, only few studies had data at 1–2 [24, 26] and 12 [30, 31, 33] months post-loss. Third, sample sizes tended to be small (N = 30–475 and five [8, 23, 25, 26, 29] out of 15 studies had < 100 subjects), limiting the power to detect potential predictors of PTSD symptoms. Finally, none were from Asian countries which may have different cultural reactions toward grief and only one study accounted for family members’ preexisting mental health and medical conditions [7]. Thus, this study aimed to comprehensively examine the course and predictors of PTSD over the first bereavement year among a large cohort of Taiwanese family members whose beloved died in the ICU. This study specifically focused on investigating the modifiable factors that contribute to EOL-care quality in ICUs.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

In this prospective, longitudinal observational study, we extended our previous studies that assessed process-based quality of EOL care in ICUs [35] and associations between the quality indicators of EOL care in ICUs and bereaved family members’ anxiety and depressive symptoms [36] to a larger sample size and examined associations of EOL-care quality in ICUs with development of PTSD symptoms among bereaved family members. Patients and their primary family members were consecutively recruited from January 2018 to January 2020 and followed through December 2020 from two academically affiliated level III medical ICUs in Taiwan (223 and 201 beds, respectively). All study ICUs were staffed by intensivists, had a 1:2 nurse-to-patient ratio per shift, and implemented an open visiting policy. Palliative care, a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, and formal family meetings for dying patients were not mandated but were promoted by the Taiwanese government. Bed-side physician-family prognostic and EOL-care discussions were commonly conducted.

Sampling strategy and study participants

Eligible ICU patients were identified as those at high risk of death, i.e., had an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score ≥ 20. Patients who died within 3 days of ICU admission were excluded, as time did not allow for the implementation of high-quality EOL care [8, 9, 25, 30]. Eligible adult family members were those who self-identified as having legal authority to act as a surrogate for their beloved’s medical decisions. This study was approved (201700343B0). Each patient’s legal family surrogate signed informed consent for their participation and for reviewing the patient’s medical record.

Measures

Outcome variable

Posttraumatic stress-related symptoms (PTSD symptoms) of bereaved family members were measured by the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), a 22-item questionnaire with established test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and concurrent validity for ICU patients’ family members [37, 38]. The IES-R cannot diagnose PTSD but acts as a screening instrument for PTSD symptoms and is most widely used with ICU family members [8, 9, 23,24,25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33,34] as indicated by a systematic review [39]. The IES-R has three subscales: intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Each item is rated for its distress level during the past week on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). IES-R scores ≥ 33 indicate clinically significant likelihood of PTSD, with a sensitivity of 0.91 and specificity of 0.82 [37]. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) and test–retest reliability of the IES-R ranged 0.925–0.953 and 0.693–0.868, respectively, over the first bereavement year.

Independent variables

Chart-derived, process-based indicators of high-quality EOL care in ICUs [13] were selected to focus on communication with and psychosocial support for family members in order to facilitate informed EOL-care decision-making and limit potentially inappropriate LSTs. These indicators included physician-family prognostic communication, family meetings conducted, palliative care provided, social worker involvement, a DNR issued prior to death, death without cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), withdrawal of any LSTs, and family presence at death [13, 35].

Family satisfaction with EOL care in ICUs was evaluated by the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire (FS-ICU) [40, 41]. The FS-ICU Care subscale (14 items) assesses (1) satisfaction with information access, (2) care quality, continuity, and accessibility, and (3) ICU and waiting room atmosphere. The FS-ICU Decision-Making subscale (10 items) measures family satisfaction with the content, completeness, and consistency of information received, as well as the amount and quality of support received during the decision-making process. Item responses were rescaled from the original 1–5 Likert scale to a scale from 0 (least satisfied) to 100 (most satisfied). Two items were removed from the total FS-ICU Care score as they were rated as “not applicable” by > 20% of family participants [41] (agitation management, 31.29% and waiting room atmosphere, 56.32%).

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics included gender, age, diagnosis (cancer vs. others), disease severity (APACHE II scores), and ICU length of stay (LOS). We explored comorbidity for patients by examining whether any of 21 common diseases (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular disease, congenital heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc.) other than the underlying primary disease were recorded in the medical chart. If any diseases other than the underlying primary disease were recorded, we coded the variable of comorbidity as “yes,” otherwise as “no.”

Family characteristics included gender, age, relationship to patient (spouse, child, or other), education level (≤ or > junior high school), financial sufficiency to make ends meet (yes or no), preexisting mental health or medical conditions, and social support. Preexisting conditions were evaluated by the 7-item Mental Health Questionnaire [7]. Items include the frequency of emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and pain or mood medication use the year before the patients’ critical illness. These questions were re-categorized into “yes” or “no.” Perceived social support was measured by the 19-item Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) [42], which assesses emotional, informational, tangible, and affectionate support, as well as positive social interaction. The total score was computed and transformed to range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better perceived support.

Data collection

Patients’ and family members’ demographics and preexisting comorbidities were recorded at enrollment. Patient disease severity (APACHE II scores) was assessed over the ICU stay. Data for patient-level process-based quality measures over the ICU stay were extracted from medical records by trained, experienced research assistants with adequate inter-rater reliability [35]. Family members’ PTSD symptoms and perceived social support were assessed in telephone interviews by trained, experienced research assistants at 1, 3, 6, and 13 months post-loss. The telephone interview is semi-structured—data collectors were instructed to interview study participants with example scripts but were free to modify the interview scripts based on participants’ needs. To ensure uniformity of data collection, prior to launch of this study, research assistants’ reliability in data collection was confirmed by comparing the data they collected with that recorded by the principal investigator on five pilot cases and among research assistants for inter-rater reliability on another five pilot cases with a minimum of 95% agreement required. To maintain 95% inter-rater reliability, the principal investigator intermittently checked agreement on reliability throughout the study. Phone calls were made during different periods over a week (e.g., morning and evening, different weekdays) if the first attempt failed to reach participants. Telephone interviews were conducted at 1 month post-loss because PTSD symptoms are those that persist ≥ 1 month after traumatic exposure [37], and at 13 months post-loss to avoid measuring the anniversary effect. Family satisfaction with EOL-care quality was assessed 1 month post-loss only.

Statistical analysis

A multivariate logistic regression analysis with the generalized estimating equation method was used to examine associations between the proposed predictors and clinically significant PTSD symptoms (IES-R score ≥ 33) among family members over their first bereavement year. APACHE II scores and process-based quality measures of EOL care last measured prior to the patient’s death were used for statistical analysis. The regression estimate for each independent variable in the logistic regression models was exponentiated to transform into adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Participant characteristics

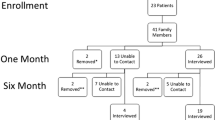

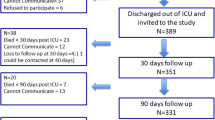

Among the 353 recruited patients (Fig. 1), 319 family members (90.37%) participated in bereavement surveys and constituted the study participants. Bereavement surveys at 1, 3, 6, and 13 months post-loss were completed by 309, 298, 274, and 248 family members, respectively (Fig. 1). Participants and non-participants of bereavement surveys (either declined at the beginning or withdrew participation) did not differ in patient (Additional file 1: Table S1) or family (Additional file 2: Table S2) demographics. Characteristics of the patient and family participants are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The top three underlying diseases among patient participants were cancer (50.2%), pulmonary diseases (6.9%), and cardiovascular diseases (4.7%). Few family participants had preexisting medical conditions. The process-based indicators of high-quality EOL care in ICUs are shown in Table 3. Family satisfaction with the care and decision-making process in ICUs was low (Table 3).

Predictors of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members in the first bereavement year

Clinically significant PTSD symptoms were found in 11.0%, 3.7%, 1.1%, and 1.6% of bereaved family members at 1, 3, 6, and 13 months post-loss, respectively. The likelihood of having clinically significant PTSD symptoms was lower at 3 months (AOR [95% CI] = 0.062 [0.016, 0.244]), 6 months (0.052 [0.018, 0.146]), and 13 months (0.214 [0.106. 0.431]) than at 1 month post-loss (Table 4).

Among patient characteristics, only ICU LOS was associated with clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members (AOR increased by 1.036 [95% CI = 1.006, 1.066] with each additional day in the ICU). Among the family member characteristics, only financial insufficiency and pain medication use within the past year was associated with increased likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms (AOR = 3.166 [1.159, 8.647] and 3.408 [1.230, 9.441], respectively). However, stronger perceived social support was negatively associated with clinically significant PTSD symptoms (AOR reduced by 0.937 [95% CI = 0.911, 0.965] with each unit increase in the MOS-SSS score).

Among the process-based indicators of high-quality EOL care in ICUs, only a DNR order issued before death was associated with a lower likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms (AOR = 0.073 [0.011, 0.490]) (Table 4). Having a higher level of satisfaction with the care or decision-making process in ICUs was associated with a lower likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms, but this was not significant (AOR = 0.988 [0.944, 1.034] and 0.980 [0.944, 1.018], respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, the prevalence of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members of deceased ICU patients decreased significantly over the first bereavement year (from 11.0% at 1 month to 1.6% at 13 months post-loss). Even though a similar trend was seen in prior studies [30, 31, 33], the observed prevalence of clinically significant PTSD symptoms in our study was substantially lower than that reported in other longitudinal (19–46.2% at 3–12 months post-loss) [30, 31, 33, 34] and cross-sectional studies (14–51% at 3–18 months post-loss) [7, 28, 29, 32]. Of note, the reported prevalence of clinically significant PTSD symptoms measured by self-reported screening instruments (including the IES-R) was 20.2% (95% CI 16.6–24.0%) among adult critical care survivors [43], 3.3–35.1% among burn survivors during hospitalization [44], 7.3% (4.5–11.7%)–13.8% (9.5–19.6%) among cancer survivors [45]. All these populations experience traumatizing diseases and treatments. Our observed prevalence of clinically significant PTSD symptoms was closer to other reports: 3–62% among family caregivers of ICU survivors [14] and 11.6% (9.6–11.6%) among parents of children with cancer [46].

The lower rates of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among the bereaved family caregivers in our study, as compared to those reported in studies from Western countries [7,8,9, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34], may be due to the cultural difference in grief reactions between Taiwanese and Western cultures. In Taiwanese culture, caring for an ill relative is viewed as a natural part of family life based on the concept of filial duty rooted in Confucian doctrines [47]. Family members in Asian cultures, which are more family-oriented, are willing to help each other adjust to the loss of a beloved by providing stronger financial and emotional support [48] than those from Western cultures, which are more individualistic. Thus, bereaved Taiwanese family members’ risk of significant PTSD symptoms may be lower.

The high rate (50.2%) of cancer patients in our study may be another reason for our low prevalence of significant PTSD symptoms. Azoulay et al. report cancer diagnosis as a factor predisposing family members to more severe PTSD symptoms [9]. However, this finding may be confounded by other factors, such as patient’s death in the ICU and the need for family to make EOL-care decisions, which were both associated with higher rates of PTSD [9]. The terminal-illness trajectory for cancer patients is commonly anticipated and predictable than the sudden and unexpected illness trajectory from cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases. In our study, family members of cancer patients had a lower likelihood of significant PTSD symptoms than those of patients with non-cancer diagnoses. However, this did not reach a statistical significance, likely due to the low prevalence of significant PTSD symptoms in our study. The specific characteristics of dying and death from cancer may reduce the overwhelming and uncontrollable trauma due to a beloved’s death.

We intended to focus on associations between quality indicators of EOL care in ICUs and clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members during the first bereavement year. We did not find many significant associations for either process-based indicators [28] of or family satisfaction with EOL care in ICUs [8, 25, 26], which is consistent with prior studies. We observed low family satisfaction with care (mean [SD] = 67.14 [16.30]) and decision-making process (72.60 [14.76]) in ICUs which may be attributable to different expectations of care in differing health care contexts as reported [49], but further cross-country and -cultural comparisons of SF-ICU are warranted.

However, having a DNR order documented before death was associated with a lower likelihood of clinically significant PTSD symptoms among family members (AOR [95% CI] = 0.073 [0.011, 0.490]). Taiwan’s government has launched multiple nationwide projects to facilitate dissemination of hospice philosophy and palliative care services over the past three decades with the help from non-governmental organizations. The goal of these efforts was to improve the quality of EOL care, with an emphasis on promoting DNR orders and avoidance of LSTs that do not benefit patients at EOL. The Taiwanese government promotes DNR orders by legislation and by educating health care professionals. This facilitates prognostic disclosure and respects patient’s and family’s wishes to forgo LSTs, minimizing suffering and allowing patients to die in peace. Therefore, having a DNR order may help prevent bereaved family members from experiencing a traumatized loss and developing significant PTSD symptoms.

However, despite the high prevalence of having a DNR order documented before death, Taiwanese patients dying in ICUs heavily used life support until death (79.31%) with few decisions to withdraw LSTs (20.69%). This paradox may be attributable to Taiwanese physician and family factors in withdrawing LSTs. ICU physicians in Asia, including in Taiwan, report being less likely than Western physicians to withdraw LSTs, but more likely to “do everything” for a patient with an irreversible condition like severe septic shock [50]. Most importantly, Taiwanese family members have a strong cultural obligation based on the Confucian doctrine of filial duty [47] to use every possible means to keep a beloved alive. Therefore, even if family members were fully informed of their beloved’s poor prognosis and were advised by physicians to withdraw LSTs, they might hesitate to initiate or accept the suggestion, especially for those whom withdrawal is interpreted as inducing immediate death, e.g., mechanical ventilation support or vasopressors. Such physician-family disagreement on the use of LSTs may partially contribute to our observed low satisfaction with care and decision-making in ICUs but warrants further cross-cultural investigation.

ICU length of stay was the only patient factor that was associated with bereaved family members’ likelihood of significant PTSD symptoms. This was contrary to the lack of association previously reported [24]. However, McGiffin and colleagues [15] suggested that if the ICU environment was itself a traumatic stressor, then incremental increases in ICU exposure (e.g., longer ICU stays) may be expected to approximate a dose–response relationship to worse psychological outcomes. Our study provides empirical support to this notion: spending more time in an ICU increased family members’ likelihood of significant PTSD symptoms during the first bereavement year.

We found that reported financial insufficiency increased family member’s risk of significant PTSD symptoms [14, 33], whereas stronger perceived social support decreased the risk. Furthermore, family members who reported receiving medical care in the year prior to the patient’s critical illness were generally more likely to develop significant PTSD symptoms, consistent with a prior study [7]. This trend reached significance in family members who reported using medications for pain, which is dissimilar from Gries and colleagues’ finding [7] that use of medication for mood is positively associated with PTSD symptoms. Our finding may be attributable to the fact that Asian people tend to somatize their emotional distress by reporting pain [51] to avoid stigmatization from psychiatric disorders [52]. Further investigation of PTSD symptoms across cultures and socioeconomic class is needed.

Our study has several limitations. Participants were sampled from only two hospitals in Taiwan, which may limit generalizability of our findings to national/international populations, especially considering cultural variations in grief reactions during bereavement in Western and Eastern countries [47]. Our findings need to be replicated in countries where cultural, societal, and health care characteristics are substantially different. Our results do not apply to family members of patients who died within 3 days of ICU admission, or to those who withdrew from post-loss surveys. PTSD symptoms were measured with the IES-R, which is not diagnostic of PTSD, thereby likely overestimating the prevalence of PTSD. However, this characteristic also helps prevent providers from overlooking the family’s need for psychological support. Our study cannot infer a causal relationship or exclude the possible impact of unmeasured factors, e.g., concordance between family members’ preferred and actual decision-making roles and physician-family agreement on appropriateness of treatment which may be more powerful than the current identified indicators of high-quality EOL care in ICUs in association with bereaved family members’ PTSD symptoms. We did not include anxiety or depressive symptoms as potential predictors but we will explore associations among these three types of psychological distress in a forthcoming study.

Conclusion and clinical implications

The prevalence of clinically significant PTSD symptoms experienced by family members of deceased ICU patients decreased significantly over the first bereavement year. The risk was lower with stronger perceived social support, when a DNR order was issued before the patient’s death. However, the risk was higher with longer ICU stays and if a family member reported financial insufficiencies or pain medication used the year prior to the patient's critical illness. During EOL care for ICU patients, special attention should be directed to family members at risk for significant PTSD symptoms, especially when ICU stays are longer, or when family members suffer from pain, face financial hardship, or have weak social support. Facilitating a DNR order before the patient’s death not only avoids unnecessary ICU patient suffering [48], but also decreases bereaved family members’ risk of significant PTSD symptoms, thus reducing tremendous costs to individuals [16,17,18,19,20], health care systems, and society [21, 22].

Availability of data and material

The sharing of anonymized data from this study is restricted due to ethical and legal constrictions. Data contain sensitive personal health information, which is protected under The Personal Data Protection Act, thus making all data requests subject to Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Per Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH) IRB, the data that support the findings of this study are restricted for transmission to those outside the primary investigative team. Data sharing with investigators outside the team requires IRB approval. All requests for anonymized data will be reviewed by the research team and then submitted to the CGMH IRB for approval.

Code availability

Specifications for data abstraction from the medical records and SAS codes for statistical analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CPR:

-

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- DNR:

-

do not resuscitate

- EOL:

-

end of life

- FS-ICU:

-

Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IES-R:

-

Impact of Event Scale-Revised scale

- LSTs:

-

life-sustaining treatments

- MOS-SSS:

-

Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey

- PTSD:

-

posttraumatic stress disorder

References

Weissman GE, Kerlin MP, Yuan Y, et al. Population trends in intensive care unit admissions in the United States among Medicare beneficiaries, 2006–2015. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(3):213–5.

Ewbank L, Thompson J, McKenna H, Anandaciva S. NHS hospital bed numbers: past, present, future. Available online March 2020: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-hospital-bed-numbers. Accessed 26 Dec 2021.

Lai CC, Ho CH, Chang CL, et al. Critical care medicine in Taiwan from 1997 to 2013 under National Health Insurance. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(8):4957–65.

Chen K, Wallace SK, Nates JL. ICU utilization: current trends in ICU beds, use, occupancy, and costs in the United States. Oncol Crit Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74698-2_5-1.

Weissman GE, Kerlin MP, Yuan Y, et al. Potentially preventable intensive care unit admissions in the United States, 2006–2015. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(1):81–8.

Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions among US Medicare beneficiaries, 2000–2015. JAMA. 2018;320(3):264–71.

Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–7.

Jensen HI, Gerritsen RT, Koopmans M, et al. Families’ experiences of intensive care unit quality of care: development and validation of a European questionnaire (euroQ2). J Crit Care. 2015;30(5):884–90.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–94.

Sprung CL, Truog RD, Curtis JR, et al. Seeking worldwide professional consensus on the principles of end-of-life care for the critically ill. The consensus for worldwide end-of-life practice for patients in intensive care units (WELPICUS) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(8):855–66.

Halpern SD, Becker D, Curtis JR, et al. The choosing Wisely® top 5 list in critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(7):818–26.

Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–22.

Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2255–62.

Johnson CC, Suchyta MR, Darowski ES, et al. Psychological sequelae in family caregivers of critically ill intensive care unit patients. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(7):894–909.

McGiffin JN, Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Is the intensive care unit traumatic? What we know and don’t know about the intensive care unit and posttraumatic stress responses. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(2):120–31.

Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(12):2518–26.

Gradus JL. Prevalence and prognosis of stress disorders: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:251.

Watson P. PTSD as a public mental health priority. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(7):61.

Weber FC, Norra C, Wetter TC. Sleep disturbances and suicidality in posttraumatic stress disorder: an overview of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:167.

Campbell SB, Renshaw KD. Posttraumatic stress disorder and relationship functioning: a comprehensive review and organizational framework. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;65:152–62.

Bothe T, Jacob J, Kröger C, Walker J. How expensive are post-traumatic stress disorders? Estimating incremental health care and economic costs on anonymised claims data. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(6):917–30.

von der Warth R, Dams J, Grochtdreis T, König HH. Economic evaluations and cost analyses in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1753940.

Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–6.

Pillai LV, Ambike D, Husainy S, et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in relatives of severe trauma patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2010;10:181–6.

Sundararajan K, Martin M, Rajagopala S, Chapman MJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in close relatives of intensive care unit patients’ evaluation (PRICE) study. Aust Crit Care. 2014;27(4):183–7.

Trevick SA, Lord AS. Post-traumatic stress disorder and complicated grief are common in caregivers of neuro-ICU patients. Neurocrit Care. 2017;26(3):436–43.

Wendlandt B, Ceppe A, Choudhury S, et al. Modifiable elements of ICU supportive care and communication are associated with surrogates’ PTSD symptoms. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(5):619–26.

Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, et al. ICU care associated with symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of patients who die in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(4):795–801.

Hartog CS, Schwarzkopf D, Riedemann NC, et al. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a patient-based questionnaire of intensive care unit staff perception and relatives’ psychological response. Palliat Med. 2015;29(4):336–45.

Kentish-Barnes N, Seegers V, Legriel S, et al. CAESAR: a new tool to assess relatives’ experience of dying and death in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(6):995–1002.

Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1341–52.

Probst DR, Gustin JL, Goodman LF, et al. ICU versus non-ICU hospital death: family member complicated grief, posttraumatic stress, and depressive symptoms. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(4):387–93.

Robert R, Le Gouge A, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Terminal weaning or immediate extubation for withdrawing mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients (the ARREVE observational study). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1793–807.

Downar J, Koo E, des Ordons AR, et al. Prevalence and predictors of severe grief reactions and desire for support following a death in the intensive care unit: a multicentre observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(4):521–2.

Lo ML, Huang CC, Hu TH, et al. Quality assessments of end-of-life care by medical record review for patients dying in intensive care units in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60(6):1092–9.

Tang ST, Huang CC, Hu TH, et al. End-of-life-care quality in intensive care units is associated with family surrogates’ severe anxiety- and depressive symptoms during their first 6 months of bereavement. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(1):27–37.

Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale—revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. p. 399–411.

Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–96.

Petrinec AB, Daly BJ. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-ICU family members: review and methodological challenges. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(1):57–78.

Heyland DK, Tranmer JE. Measuring family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: the development of a questionnaire and preliminary results. J Crit Care. 2001;16(4):142–9.

Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Heyland DK, Curtis JR. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):271–9.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sc Med. 1991;32(6):705–14.

Righy C, Rosa RG, da Silva RTA, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):213.

Giannoni-Pastor A, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Fidel Kinori SG, Arguello JM, Casas M. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress symptomatology among burn survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37(1):e79-89.

Cordova MJ, Riba MB, Spiegel D. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):330–8.

van Warmerdam J, Zabih V, Kurdyak P, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children with cancer: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(6):e27677.

Lee L. Filial duty as the moral foundation of caring for the elderly: its possibility and limitations. In: Fun RP, editor. Family-oriented informed consent: East Asian and American perspectives. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 137–47.

Chow AY, Chan CL, Ho SM. Social sharing of bereavement experience by Chinese bereaved persons in Hong Kong. Death Stud. 2007;31(7):601–18.

Morales LS, Elliott MN, Weech-Maldonado R, et al. Differences in CAHPS adult survey reports and ratings by race and ethnicity: an analysis of the National CAHPS benchmarking data 1.0. Health Serv Res. 2001;36:595–617.

Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):363–71.

Ahmad F, Maule C, Wang J, Fung WLA. Symptoms and experience of depression among Chinese communities in the west: a scoping review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2018;26(6):340–51.

Zhang Z, Sun K, Jatchavala C, et al. Overview of stigma against psychiatric illnesses and advancements of anti-sigma activities in six Asian societies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1):280.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX110-10704PI) with partial support from Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 108-2314-B-182-061-MY3) and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (BMRP888).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding author (Tang ST) takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, has full access to all of the data in the study, and is responsible for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. HCC, HTH, CWC, CLP, CMC, and TST contributed substantially to the study conception and design. HCC, HTH, CWC, CLP, CMC contributed by providing study patients. HCC, HTH, CWC, CLP, CMC, and TST contributed to collection and/or assembly of data. HCC, HTH, CWC, CLP, CMC, and TST contributed to data analysis and interpretation. HCC, HTH, CWC, CLP, CMC, and TST contributed to the writing and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The central Institutional Review Board of the study sites approved this study (201700343B0).

Consent to participate

Each patient’s legal family surrogate signed informed consent for reviewing the patient’s medical record and their own participation.

Consent for publication

All authors have read the manuscript and consented for this manuscript to be published by Intensive Care Medicine.

Competing interests

The authors declare no financial or other conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Comparisons of patient characteristics at enrollment.

Additional file 2

. Family caregiver characteristics at enrollment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, S.T., Huang, CC., Hu, TH. et al. Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress-related symptoms among family members of deceased ICU patients during the first year of bereavement. Crit Care 25, 282 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03719-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03719-x