Abstract

Renal replacement therapy (RRT) is a key component in the management of severe acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill patients. Many cohort studies, meta-analyses, and two recent large randomized prospective trials which evaluated the relationship between the timing of RRT initiation and patient outcome remain inconclusive due to substantial differences in study design, patient population, AKI definition, and RRT indication. A cause-specific diagnosis of AKI based on current staging criteria plus a sensitive biomarker (panel) that allows creating a homogeneous study population is definitely needed to assess the impact of early versus late initiation of RRT on patient outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common yet highly devastating complication in critically ill patients [1]. AKI is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [2]. Renal replacement therapy (RRT) remains a cornerstone of AKI treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU). However, RRT is a double-edged “therapeutic” sword, in particular with regard to timing of intervention [3]. Early initiation may control fluid and electrolyte status more efficiently, more rapidly correct acid–base homeostasis, remove uremic toxins appropriately, and perhaps prevent subsequent complications attributable to AKI [4]. RRT initiated before the onset of severe AKI could potentially prevent the kidney-specific damage and remote organ injury resulting from fluid overload, electrolyte–metabolic imbalance, and systemic inflammation. However, early initiation of RRT may also unnecessarily expose patients, who might recover from AKI without RRT, to unwarranted complications associated with RRT use. These complications include hemodynamic instability, coagulation disorders, bloodstream infection, and even inflammatory or oxidative stress induced by bio-incompatibility reactions to dialyzer membranes [5]. Late initiation of RRT may provide time to stabilize the patient’s condition or more adequately treat underlying diseases so that unnecessary renal support is avoided [6]. However, acting too late holds a potential risk of delaying crucial therapy and may worsen prognosis.

The timing of RRT initiation and outcome: an elephant touched by blind men?

Seabra et al. analyzed 23 studies including five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and reported a significant survival benefit when RRT was started early. The observed benefit was predominantly found in cohort studies but was not confirmed in the RCTs [7]. Karvellas et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 13 observational studies and two small RCTs. They also demonstrated a significant benefit in 28-day survival in the early RRT group [8]. In contrast, an extensive evidence-based systematic review enrolling the most recently published studies concluded that early RRT did not improve patient survival or confer reductions in ICU or hospital length of stay [9]. These incongruous results are due to differences in study quality, publication bias, heterogeneous patient populations (e.g. medical vs surgical patients), various AKI definitions and subtypes, and different cutoff points at which clinicians decide to start RRT (e.g., urine output, metabolic variables, AKI severity, or temporal relationship with particular events) [8,9,10].

AKI definitions which are based essentially on the measurement of urinary output and serum creatinine levels have been refined progressively for diagnostic, prognostic, and research purposes. Expert panels have successively proposed the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage (RIFLE) renal disease criteria in 2004, [11] the AKI Network (AKIN) criteria in 2007 [12], and the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI criteria in 2012 [13]. Studies that applied these RIFLE, AKIN, or KDIGO criteria to evaluate patient outcomes related to the early or late timing of RRT initiation are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Observational studies demonstrate better outcome in patients receiving early RRT treatment but this is not confirmed in RCTs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Of note is that many studies are retrospective or prone to a type I error in hypothesis testing due to significant differences in preintervention study groups [9].

The AKIKI and ELAIN trials: any solace?

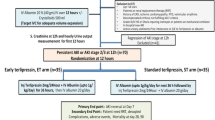

Two recently published large prospective RCTs, the Artificial Kidney Initiation in Kidney Injury (AKIKI) trial [23] and the Early versus Late Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury (ELAIN) trial [24], have assessed the impact of different RRT timing in severely ill ICU patients with AKI without potentially life-threatening complications. The AKIKI and ELAIN trial concepts are outlined in Table 3. The AKIKI trial [23] enrolled 620 ICU patients on mechanical ventilation and/or catecholamine infusion with KDIGO stage 3 AKI. No significant difference in 60-day mortality was found between early and delayed RRT. The ELAIN trial [24] included 231 ICU patients with KDIGO stage 2 AKI and exhibiting a plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) level above 150 ng/ml. Compared with delayed treatment, an early strategy resulted in lower 90-day mortality, more rapid recovery of renal function, and a significantly shorter duration of hospital stay.

The discrepant outcome result between both trials is confusing but can be explained by important methodological differences. First, the AKIKI trial was conducted in 31 ICUs screening 5528 predominantly medical patients for 25 months to finally randomize 620 (11%) subjects. The ELAIN trial was a single-center trial conducted over a similar time period but screening only 604 almost exclusively postsurgical and trauma patients to include 231 (38%) subjects. This suggests potential patient selection, inclusion, and treatment bias. Second, patients in the ELAIN trial received delayed RRT more “early” than their AKIKI counterparts (25.5 h vs 57 h). The modest difference in RRT initiation time in the ELAIN trial is also difficult to reconcile with the observed positive effects on outcome. Third, both trials included patients with different disease severity and AKI etiology. Patients with refractory pulmonary edema were excluded in the AKIKI trial but accounted for three-quarters of ELAIN inclusions. ELAIN patients had more nonrenal organ dysfunction (as shown by a higher baseline Sequential Organ failure Assessment score at enrollment). Also, septic AKI which was more prevalent in AKIKI patients and postoperative AKI have different pathophysiology and prognosis. Fourth, according to the applied AKI definition, patients entering the AKIKI trial all had at least “renal failure” (KDIGO stage 3 AKI) whereas this was only the case for the delayed ELAIN treatment group. Patients receiving early treatment in the ELAIN trial were thus included with “less severe” AKI, which could have beneficially influenced outcome. Fifth, initial RRT modalities were at the discretion of the enrolling AKIKI investigators which resulted in a mix of continuous and intermittent RRT techniques. In contrast, all patients in the ELAIN trial were started on continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration and the majority was transitioned to daily sustained low-efficiency dialysis. The latter technique was never employed in AKIKI patients. Differences in fluid and metabolic dynamics between various RRT modalities may have determined hemodynamic assessment, treatment, and outcome in a substantial number of patients. Finally, up to half of the patients allotted to late treatment in the AKIKI trial ultimately did not receive RRT. This cohort had the lowest mortality rate (37.1%) as compared with patients receiving either early (48.5%) or late (61.8%) RRT. Despite adjustment for baseline severity of illness, the impact of protocol-associated patient selection and protocol-mandated delay in RRT on outcome should be considered [25, 26].

STARRT-AKI trial: another touch of the elephant?

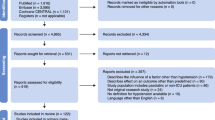

Besides the two aforementioned RCTs, another ongoing large multinational, multicenter RCT, the “STandard Versus Accelerated Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury (STARRT-AKI)” trial, deserves attention. The STARRT-AKI trial aims to enroll a large number of patients worldwide (2866 subjects in more than 60 sites across countries) and thus is expected to be more representative than the AKIKI and ELAIN trials. Moreover, the choice for early or delayed initiation of RRT in this trial will be determined by a “KDIGO stage 2” or by “specific clinical criteria” respectively, which more closely reflects current ICU practice [27]. Although plasma NGAL has low indicating power for estimating the possibility of AKI progression or the optimal timing for RRT initiation [27], the fact that no biomarker is selected for screening or risk stratification purposes might be a potential shortcoming of this trial.

Practical implications and prospects: we plea for a universal AKI definition!

AKI is a complex disorder with many potential (i.e., septic, ischemic, or toxic) triggers. Prerenal, intrarenal, and postrenal disorders may either alone or in combination contribute to AKI severity and progression [28]. All of these factors finally will determine patient outcome. On top of this, RRT is increasingly implemented in the treatment of AKI, even in the absence of life-threatening hemodynamic or metabolic conditions. Basing decisions on creatinine concentrations or urinary output is unreliable in critically ill ICU patients. Moreover, the prognosis may also vary in patients who are diagnosed with similar AKI stage at different time points (e.g., at admission or during hospitalization) [28, 29]. Thus, currently applied AKI criteria should be adapted and perhaps strengthened by adding sensitive functional and structural biomarkers [28, 29].

Several novel biomarkers have been introduced as an aid to identify patients with AKI earlier, to evaluate severity of kidney injury, to differentiate type and etiology of injury, and to assess the effect of interventions on renal recovery [30, 31]. Some biomarkers may even independently detect AKI progression regardless of glomerular filtration rate changes [32]. Actual biomarkers lack specificity for correctly assessing the time of AKI occurrence but are useful for risk stratification in severe AKI and for determining the need for RRT or mortality prediction [30, 33]. Furthermore, a clinical approach supported by biomarker assessment performed better than a pure clinical [34] or biomarker [35] model to predict relevant outcome variables such as AKI progression, recovery of renal function, need for RRT, and death.

We strongly believe that adding biomarker measurement to existing AKI classifications would more accurately confirm both the presence and severity of AKI and allow appropriate stratification and inclusion of patients in well-designed RCTs. This is imperative to correctly assess the real impact of early versus late RRT initiation on patient outcome. Maybe then we will behold the whole elephant!

Dose of RRT: another factor to take into account?

Theoretically, the prescribed and delivered RRT dose and the timing of RRT initiation must both be considered for controlling uremia in AKI patients [36]. In fact, the dose of RRT may be of prognostic importance if uremic waste product concentration and exposure time become significant. However, “more intensive” RRT has not been shown to improve outcome of critically ill patients with AKI [37]. Studies evaluating the association between RRT dose and outcome also remain difficult to interpret because heterogeneous patient populations were included and different RRT techniques applied [37,38,39,40]. Finally, the studies did not address “early vs late” initiation of RRT [36,37,38,39,40].

Consensus is accruing that the delivered RRT dose must be tailored to the needs of an individual patient suffering severe AKI [36]. In addition, investigators will need to carefully consider the RRT dose when evaluating timing of RRT. A paradigm shift in RRT management is evolving and may include an “early” (or delayed) start with a higher (or lower, or initial “higher” followed by “lower”) dose of RRT.In our opinion, RRT strategies should be adapted to particular patient populations. Designing future studies will definitely become more challenging, yet is the only way forward to provide valuable answers on crucial but still unsolved issues in critical care nephrology.

Conclusions

Because of the substantial differences in study design, patient population, AKI definition, and RRT indication, no conclusive consensus can be generated from existing prospective and retrospective cohort studies, meta-analyses, and the two recent large RCTs which evaluated the relationship between the timing of RRT initiation and patient outcome. There is an urgent need for a cause-specific diagnostic criterion of AKI. We suggest that implementing a sensitive biomarker (panel) on top of current staging classification may allow defining a homogeneous study population to assess the impact of early versus late initiation of RRT on patient outcome.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- AKIKI:

-

Artificial Kidney Initiation in Kidney Injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- ELAIN:

-

Early vs Late Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

- NGAL:

-

neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RIFLE:

-

Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

References

Li PK, Burdmann EA, Mehta RL. Acute kidney injury: global health alert. Kidney Int. 2013;83:372–6.

Pannu N, James M, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S. Association between AKI, recovery of renal function, and long-term outcomes after hospital discharge. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:194–202.

Schneider AG, Bellomo R, Bagshaw SM, Glassford NJ, Lo S, Jun M, et al. Choice of renal replacement therapy modality and dialysis dependence after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:987–97.

Wald R, Bagshaw SM. The timing of renal replacement therapy initiation in acute kidney injury: is earlier truly better? Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1933–4.

Shiao CC, Wu PC, Huang TM, Lai TS, Yang WS, Wu CH, et al. Long-term remote organ consequences following acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2015;19:438.

Shingarev R, Wille K, Tolwani A. Management of complications in renal replacement therapy. Semin Dial. 2011;24:164–8.

Seabra VF, Balk EM, Liangos O, Sosa MA, Cendoroglo M, Jaber BL. Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation in acute renal failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:272–84.

Karvellas CJ, Farhat MR, Sajjad I, Mogensen SS, Leung AA, Wald R, et al. A comparison of early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15:R72.

Wierstra BT, Kadri S, Alomar S, Burbano X, Barrisford GW, Kao RLC. The impact of "early" versus "late" initiation of renal replacement therapy in critical care patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and evidence synthesis. Crit Care. 2016;20:122.

Lai TS, Shiao CC, Wang JJ, Huang CT, Wu PC, Chueh E, et al. Earlier versus later initiation of renal replacement therapy among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:38.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–12.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31.

KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for acute kidney injury- Section 2: AKI definition. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2012;2:19–36.

Sabater JP, Albertos R, Gutierrez D, Labad X. Acute renal failure in septic shock: should we consider different continuous renal replacement therapies on each RIFLE score stage? Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:S239.

Shiao CC, Wu VC, Li WY, Lin YF, Hu FC, Young GH, et al. Late initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with worse outcomes in acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery. Crit Care. 2009;13:R171.

Chou YH, Huang TM, Wu VC, Wang CY, Shiao CC, Lai CF, et al. Impact of timing of renal replacement therapy initiation on outcome of septic acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2011;15:R134.

Wu SC, Fu CY, Lin HH, Chen RJ, Hsieh CH, Wang YC, et al. Late initiation of continuous veno-venous hemofiltration therapy is associated with a lower survival rate in surgical critically ill patients with postoperative acute kidney injury. Am Surg. 2012;78:235–42.

Boussekey N, Capron B, Delannoy PY, Devos P, Alfandari S, Chiche A, et al. Survival in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury treated with early hemodiafiltration. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35:1039–46.

Hu ZJ, Liu LX, Zhao CC. Influence of time of initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy on prognosis of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2013;25:415–9.

Shum HP, Chan KC, Kwan MC, Yeung AW, Cheung EW, Yan WW. Timing for initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy in patients with septic shock and acute kidney injury. Ther Apher Dial. 2013;17:305–10.

Leite TT, Macedo E, Pereira SM, Bandeira SRC, Pontes PHS, Garcia AS, et al. Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation by AKIN classification system. Crit Care. 2013;17:R62.

Suzuki J, Ohnuma T, Sanayama H, Ito K, Fujiwara T, Yamada H. Early initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy is associated with lower mortality in patients with acute kidney injury. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:S443.

Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, Martin-Lefevre L, Pons B, Boulet E, et al. Initiation strategies for renal-replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:122–33.

Zarbock A, Kellum JA, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Wempe C, Pavenstädt H, et al. Effect of early vs delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy on mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: the ELAIN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2190–9.

Bagshaw SM, Wald R. Acute kidney injury: timing of renal replacement therapy in AKI. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:445–6.

Wyatt CM, Coca SG. Timing is everything? Reconciling the results of recent trials in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2016;90:718–21.

Bagshaw SM, Lamontagne F, Joannidis M, Wald R. When to start renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: comment on AKIKI and ELAIN. Crit Care. 2016;20:245.

Parikh CR, Moledina DG, Coca SG, Thiessen-Philbrook HR, Garg AX. Application of new acute kidney injury biomarkers in human randomized controlled trials. Kidney Int. 2016;89:1372–9.

Thomas ME, Blaine C, Dawnay A, Devonald MA, Ftouh S, Laing C, et al. The definition of acute kidney injury and its use in practice. Kidney Int. 2015;87:62–73.

Kashani K, Cheungpasitporn W, Ronco C. Biomarkers of acute kidney injury: the pathway from discovery to clinical adoption. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017. Epub ahead of print.

Cruz DN, Bagshaw SM, Maisel A, Lewington A, Thadhani R, Chakravarthi R, et al. Use of biomarkers to assess prognosis and guide management of patients with acute kidney injury. Contrib Nephrol. 2013;182:45–64.

Ferguson MA, Vaidya VS, Waikar SS, Collings FB, Sunderland KE, Gioules CJ, et al. Urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein predicts adverse outcomes in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2010;77:708–14.

Schrezenmeier EV, Barasch J, Budde K, Westhoff T, Schmidt-Ott KM. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury—pathophysiological basis and clinical performance. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2017;219:554–72.

Pike F, Murugan R, Keener C, Palevsky PM, Vijayan A, Unruh M, et al. Biomarker enhanced risk prediction for adverse outcomes in critically ill patients receiving RRT. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1332–9.

Koyner JL, Davison DL, Brasha-Mitchell E, Chalikonda DM, Arthur JM, Shaw AD, et al. Furosemide stress test and biomarkers for the prediction of AKI severity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2023–31.

Joannidis M, Forni LG. Clinical review: timing of renal replacement therapy. Crit Care. 2011;15:223.

Li SY, Yang WC, Chuang CL. Effect of early and intensive continuous venovenous hemofiltration on patients with cardiogenic shock and acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1628–33.

Network VNARFT, Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, O'Connor TZ, Chertow GM, Crowley ST, et al. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:7–20.

Investigators RRTS, Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, et al. Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1627–38.

Fayad AI, Buamscha DG, Ciapponi A. Intensity of continuous renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10: CD010613.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the TR15, CAKS, National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals, Taiwan, ROC for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by the TR15, CAKS, National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals, Taiwan, ROC.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

C-CS, T-MH, and V-CW conceived the review topic and wrote the manuscript. HDS and PMH revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shiao, CC., Huang, TM., Spapen, H.D. et al. Optimal timing of renal replacement therapy initiation in acute kidney injury: the elephant felt by the blindmen?. Crit Care 21, 146 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1713-2

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1713-2