Abstract

Introduction

Our aim was to investigate the impact of early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy (RRT) on clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury (AKI).

Methods

Systematic review and meta-analysis were used in this study. PUBMED, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Clinical Trials, and other sources were searched in July 2010. Eligible studies selected were cohort and randomised trials that assessed timing of initiation of RRT in critically ill adults with AKI.

Results

We identified 15 unique studies (2 randomised, 4 prospective cohort, 9 retrospective cohort) out of 1,494 citations. The overall methodological quality was low. Early, compared with late therapy, was associated with a significant improvement in 28-day mortality (odds ratio (OR) 0.45; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.28 to 0.72). There was significant heterogeneity among the 15 pooled studies (I2 = 78%). In subgroup analyses, stratifying by patient population (surgical, n = 8 vs. mixed, n = 7) or study design (prospective, n = 10 vs. retrospective, n = 5), there was no impact on the overall summary estimate for mortality. Meta-regression controlling for illness severity (Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II)), baseline creatinine and urea did not impact the overall summary estimate for mortality. Of studies reporting secondary outcomes, five studies (out of seven) reported greater renal recovery, seven (out of eight) studies showed decreased duration of RRT and five (out of six) studies showed decreased ICU length of stay in the early, compared with late, RRT group. Early RRT did not; however, significantly affect the odds of dialysis dependence beyond hospitalization (OR 0.62 0.34 to 1.13, I2 = 69.6%).

Conclusions

Earlier institution of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI may have a beneficial impact on survival. However, this conclusion is based on heterogeneous studies of variable quality and only two randomised trials. In the absence of new evidence from suitably-designed randomised trials, a definitive treatment recommendation cannot be made.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a serious complication of critical illness that is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [1–7]. Extracorporeal renal replacement therapy (RRT) has long been used as supportive treatment of AKI, and has traditionally focused on averting the life-threatening derangements associated with kidney failure (that is, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, uremia, and/or fluid overload) while allowing time for organ recovery. Observations from a large multinational, multicenter survey found the prevalence of severe AKI supported with RRT in critically ill patients was approximately 6% [7].

A critical decision in the support of critically ill patients with AKI is when to initiate RRT. Data have emerged to suggest that earlier RRT initiation may attenuate kidney-specific and non-kidney organ injury from acidemia, uremia, fluid overload, and systemic inflammation [8, 9]. This in turn, may potentially translate into improved survival and earlier recovery of kidney function [9]. Unfortunately, in the absence of refractory acidemia, toxic hyperkalemia and intravascular fluid overload contributing to respiratory failure, there is limited evidence to guide clinicians on when to initiate RRT in critically ill patients with AKI. The question of timing of initiation of RRT (that is, "early" versus "late") has seldom been the focus of high-quality or rigorous evaluation [10–23]. As a consequence, initiatives aimed at identifying the "optimal timing of initiation of RRT" in AKI have been given the highest priority for investigation by the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) [24, 25].

Accordingly, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine whether "early" versus "late" initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI is associated with a survival benefit or more favourable renal recovery.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted and reported according to PRISMA guidelines [26] (Additional File 1).

Search strategy

We performed a comprehensive search of MEDLINE (1985 to July 2010), PubMed, EMBASE (1985 to July 2010), the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, and Scopus to identify randomised trials and cohort studies that assessed the timing of initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI. We restricted our search to clinical studies performed in adult populations and published in the English language. We also excluded studies published prior to 1985 largely to reflect important advances in RRT technology and in critical care support not available in older studies.

We extended our search to include clinical trial registries (Controlled trials meta Register) and review of abstracts from selected scientific proceedings (Society of Critical Care Medicine, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and American Society of Nephrology). The bibliographies of all retrieved articles were also hand-searched.

Our search was based on four search themes using the Boolean operator 'OR' (Additional File 2). The first Boolean heading included keyword/MESH headings describing RRT and its different modalities. The second Boolean heading employed terms describing AKI. The third Boolean heading combined the keywords/MESH headings related to critical illness and its different populations. The fourth Boolean search included terms describing timing or initiation of therapy. The searches were combined by using the Boolean term "AND".

Study selection

Two reviewers (CK and MF/IS/SM) independently performed an initial eligibility screen of all retrieved titles and abstracts (when available). Those studies reporting original data that specifically mentioned the application of RRT in patients with AKI were selected for further review. Full-text review was independently performed by two reviewers (as above) for the following specific eligibility criteria: 1) observational cohort and/or randomised/quasi-randomised clinical trial (RCT) design; 2) adult critically ill population; 3) diagnosis of AKI; 4) description of factors related to timing of initiation of RRT; and 5) description of mortality and/or clinically relevant secondary outcomes (that is, kidney recovery and/or dialysis independence, duration of RRT, and ICU length of stay).

Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer or by discussion and consensus.

Data extraction

All data were extracted independently with standardised forms with subsequent discussion of any discrepancies. Data were collected on study characteristics and quality, demographics and baseline characteristics (that is, clinical/biochemical parameters at initiation of RRT), and details of RRT modality (that is, continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH), continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD), continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF), and intermittent hemodialysis (IHD)). The primary outcome measure was mortality. Secondary outcomes included: kidney recovery and/or dialysis independence, duration of RRT and ICU length of stay.

Assessment of methodological quality

Randomised studies were appraised using a modified version of the Jadad score [27]. Evaluation of cohort studies was done in a descriptive fashion similar to previous studies [28], incorporating the reported criteria for RRT initiation, assembly of control groups, comparability of intervention/control arms (that is, baseline characteristics, severity of illness, dialysis modality), and a description of dropouts.

Data analysis and assessment for bias

Data were analysed by STATA version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX. USA) and Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 2 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA) [29]. We assessed and quantified statistical heterogeneity for each pooled summary estimate using Cochran's Q statistic and the I2statistic, respectively [30]. Pooled analysis was performed using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model and reported as OR with 95% CIs. Meta-regression analysis was performed to assess for possible sources of heterogeneity according to the following pre-defined variables: criteria used to initiate RRT (that is, creatinine, urea, or other), severity of illness (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health (APACHE II) score), type of critical care unit (mixed medical/surgical vs. surgical alone), and study design (observational vs. RCT). Publication bias was assessed using Egger's regression model, and visualised with a funnel plot [31].

Results

Trial selection

A total of 1,494 citations were identified (Figure 1). After primary and secondary screen, 15 studies fulfilled all criteria for final analysis (13 articles and 2 abstracts).

Trial characteristics

We found two randomised trials [10, 32], four prospective cohort studies [21, 33–35], and nine retrospective cohort studies [13, 15, 36–42]. Of these, 13 were published as articles in peer-reviewed journals and 2 studies were published as abstracts only [33, 35]. Eight studies examined only patients with surgical diagnoses (that is, cardiac, abdominal, and trauma) while the remaining seven studies were from mixed medical/surgical ICUs.

Assessment of trial quality

Of the two included RCTs, one fulfilled all quality indicators [10] (Table 1), whereas the other did not describe the methods of randomisation or perform analysis by intention to treat [32]. Of the 13 cohort studies, none fulfilled all quality indicators (Table 2). Only five had a prospectively assembled control group [21, 33–35, 41], four had comparable modes of RRT between the early and late initiation groups [15, 38, 39, 41], and only three studies accounted for withdrawals/loss to follow-up [34, 35, 38].

Type of renal replacement therapy and criteria used for

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was used as the principle modality for RRT in eight studies [10, 13, 15, 32, 33, 38, 39, 41], while a combination of IHD and CRRT were used in the remaining studies [21, 34–37, 40, 42] (Table 3). Six studies defined timing of initiation of RRT based on cut-offs in serum urea [15, 21, 34, 35, 37, 42], two studies based on cut-offs in serum creatinine [33, 41], one study based on the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-stage (RIFLE) criteria [3], and four based on urine output [10, 32, 38, 40]. Three other studies used a composite of factors to designate early initiation [13, 36, 39]. Eight studies reported duration of RRT [10, 13, 15, 33, 34, 38–40] (range 1 to 20 days). Seven studies described recovery of kidney function (RRT independence) [10, 15, 32, 34, 35, 39, 41].

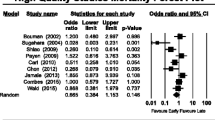

Mortality

The OR for 28-day mortality is shown in Figure 2. Overall 28-day mortality across the 15 trials was 53.3% (1,431/2,684). Early RRT initiation was associated with reduced mortality compared to late initiation (pooled OR 0.45; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.72, P < 0.001). However, there was significant statistical heterogeneity (I2= 78%, Q 63.7).

Subgroup analysis was performed according to type of ICU (mixed vs. surgery only; Figure 3). The overall effect estimate of the surgical group (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.58, n = 8) was not statistically different than that of the mixed group (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.24, n = 7) with a P-value of 0.06. There was also no statistical difference in the overall effect estimates between prospective and retrospective studies. There was also no statistically significant effect on the pooled OR for mortality when analysed according to baseline APACHE II scores, creatinine, and urea levels. Therefore, meta-regression analyses with these variables could not account for the large amounts of heterogeneity observed.

Secondary outcomes

Five studies [15, 32, 34, 39, 41] (of seven reporting data) described a higher rate of kidney recovery to dialysis independence at hospital discharge for patients receiving early RRT (Table 4). Pooled analysis of these seven studies showed a non-significant summary estimate favouring early RRT (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.13, I2 = 69.6%; Figure 4).

Due to the variability in the reporting of the remaining secondary outcomes of interest and evidence of significant statistical heterogeneity, we did not perform a pooled analysis for RRT duration or ICU length of stay. Rather, we present the data on these secondary outcomes descriptively (Table 4). Seven studies [10, 13, 15, 33, 34, 39, 40] (of eight reported data) described shorter duration of RRT in those receiving early RRT. Five studies [13, 35, 37–39] (of six reported data) described a reduction in ICU length of stay in those receiving early RRT.

Publication bias

We assessed for publication bias using Egger's linear regression test and found statistical evidence of bias (beta-coefficient of the bias estimate = -3.19, 95% CI = -4.58 to -1.81, P = 0.0003). There appears to be publication bias towards smaller studies reporting positive results (that is, mortality benefit associated with early initiation of RRT) (Figure 5).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 unique studies compared "early" versus "late" initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI and suggests that earlier initiation is associated with improved survival. There is insufficient evidence to conclude that kidney recovery to dialysis independence is influenced by the timing of RRT initiation.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to address the question of whether timing of RRT initiation has an important impact on survival and kidney recovery in the critically ill. Previous work on this issue was not specifically focused on critically ill patients supported in an ICU environment [43]. Moreover, in contrast to previous work [43], we intentionally excluded older studies (that is, published before 1985) due to the considerable advances in available technology for providing RRT, the marked demographic transition critically ill populations (that is, older, more comorbid illness, receiving more complex procedures/interventions), and the evolution in general of interventions and technology available to support the critically ill. Accordingly, our systematic review is uniquely focused on how the timing of initiation of RRT impacts survival and kidney recovery in modern ICU practice. Despite these strengths, inferences from our study are limited for two important reasons. First, we found significant statistical heterogeneity. As such, we were unable to calculate effect sizes for all secondary outcomes of interest. We attribute the observed heterogeneity to marked variability between published studies in study design and quality, which we were unable to account for in sensitivity analyses. Second, we found evidence of publication bias towards smaller studies where early initiation of RRT was associated with a survival benefit. As a consequence, the magnitude of the pooled effect estimate may overstate the `true` benefit, if any, of early compared with late RRT initiation.

Our findings are broadly consistent with those reported previously [43]. However, our study more specifically focused on the critically ill and benefited from the recent publication of several additional studies. In a previous meta-analysis [43], Seabra and colleagues explored heterogeneity but found no association between effect estimate and date of publication, RRT modality, sample size, duration of study follow-up, and study quality. Likewise, we could not account for the observed heterogeneity by meta-regression according to patient and population characteristics including type of ICU, severity of illness (baseline APACHE II scores), and metabolic derangements (baseline creatinine and urea levels). Accordingly, the heterogeneity observed is most likely explained by differences in study design (that is, clinical trial vs. cohort study), operational definitions for RRT timing (that is, clinical vs. biochemical criteria) and the inability to account for heterogeneity in clinical practice patterns. Our study has several notable strengths compared to earlier work. First, we have included eight additional clinical studies [32–35, 37, 39–41]. Second, we excluded studies for which there was no comparable control group [44–46], as well as older studies that have no applicability to current ICU practice [11, 16, 22]. Third, we have found evidence of publication bias and explain how older reports from smaller studies favouring early RRT may have influenced our summary estimates.

The utilization of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI is relatively common [7, 47]. Importantly, the incidence is increasing [48]. These critically ill patients have a risk of death approaching 60% [2, 7]. The decision to initiate RRT is a modifiable intervention for these patients; however, it also represents a significant escalation in the complexity and cost of their support. The current uncertainty over the optimal time to initiate RRT is a critical knowledge gap in evidence that has almost certainly contributed to the wide variation in clinical practice. Moreover, this has been further compounded by a lack of consensus and a standardised definition for "early" RRT [24]. There are currently numerous clinical, biochemical, and physiological factors that are considered when deciding to initiate RRT; however, there remains no consensus guidelines or rigorous evidence to guide clinicians on this important issue [24]. This is analogous to the uncertainty regarding the optimal dose-intensity of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI that was largely settled by the recent publication of two large randomised trials [49, 50]. A future randomised trial will ideally require broad-based consensus on eligibility criteria and operational definitions for 'early' and 'standard' initiation of RRT in critically ill patients to ensure feasibility and adequate separation of treatment arms. In addition, such a study may benefit from the integration of novel kidney-injury specific biomarkers to aid in the prediction of those who will develop worsening AKI. Understanding methods to further optimise the delivery of acute RRT for critically ill patients with AKI is of utmost importance to improve patient outcomes, guide resource utilization, and rationally deliver standardised care.

Conclusions

In summary, our systematic review suggests that early institution of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI may have a measurable benefit on survival. However, existing evidence is based on mostly smaller studies with important differences in design and quality, and only two randomised trials. In the absence of novel evidence from a multi-centric suitably-designed randomised trial, conclusive treatment recommendations on the optimal time to initiate RRT remain uncertain. Future investigation must be targeted at defining acceptable "early" RRT criteria and determining whether "early" initiation of RRT, compared with the current standard-of-care, has an important modifying influence on short- and long-term survival and kidney recovery.

Key messages

-

The overall design and quality of studies comparing early versus late initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI is low.

-

Earlier initiation of RRT in critically ill patients with AKI may have a beneficial impact on survival.

-

A well-designed randomised trial targeting acceptable 'early' compared with "standard" criteria for RRT initiation in homogenous patient populations is needed to definitively determine the effect of RRT timing on patient outcomes.

Authors' information

Sean Bagshaw is supported by a Clinical Investigator Award from the Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions (formerly Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research). Alexander Leung is supported by the Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions Clinical Fellowship, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Fellowship, and the John A. Buchanan Research Chair at the University of Calgary.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

acute kidney injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CRRT:

-

continuous renal replacement therapy

- CVVH:

-

continuous venovenous hemofiltration

- CVVHD:

-

continuous venovenous hemodialysis

- CVVHDF:

-

continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration

- IHD:

-

intermittent hemodialysis

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- RCT:

-

randomised control trial

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy.

References

Ahlstrom A, Tallgren M, Peltonen S, Rasanen P, Pettila V: Survival and quality of life of patients requiring acute renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med 2005, 31: 1222-1228. 10.1007/s00134-005-2681-6

Bagshaw SM, Laupland KB, Doig CJ, Mortis G, Fick GH, Mucenski M, Godinez-Luna T, Svenson LW, Rosenal T: Prognosis for long-term survival and renal recovery in critically ill patients with severe acute renal failure: a population-based study. Crit Care 2005, 9: R700-709. 10.1186/cc3879

Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, Venkataraman R, Angus DC, De Bacquer D, Kellum JA: RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care 2006, 10: R73. 10.1186/cc4915

Korkeila M, Ruokonen E, Takala J: Costs of care, long-term prognosis and quality of life in patients requiring renal replacement therapy during intensive care. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26: 1824-1831. 10.1007/s001340000726

Manns B, Doig CJ, Lee H, Dean S, Tonelli M, Johnson D, Donaldson C: Cost of acute renal failure requiring dialysis in the intensive care unit: clinical and resource implications of renal recovery. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: 449-455. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000045182.90302.B3

Morgera S, Kraft AK, Siebert G, Luft FC, Neumayer HH: Long-term outcomes in acute renal failure patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapies. Am J Kidney Dis 2002, 40: 275-279. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34505

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C: Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005, 294: 813-818. 10.1001/jama.294.7.813

Clark WR, Letteri JJ, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Ronco C: Recent clinical advances in the management of critically ill patients with acute renal failure. Blood Purif 2006, 24: 487-498. 10.1159/000095929

Matson J, Zydney A, Honore PM: Blood filtration: new opportunities and the implications of systems biology. Crit Care Resusc 2004, 6: 209-217.

Bouman CS, Oudemans-Van Straaten HM, Tijssen JG, Zandstra DF, Kesecioglu J: Effects of early high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration on survival and recovery of renal function in intensive care patients with acute renal failure: a prospective, randomized trial. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 2205-2211. 10.1097/00003246-200210000-00005

Conger JD: A controlled evaluation of prophylactic dialysis in post-traumatic acute renal failure. J Trauma 1975, 15: 1056-1063. 10.1097/00005373-197512000-00003

Cosentino F, Chaff C, Piedmonte M: Risk factors influencing survival in ICU acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994, 9 Suppl 4: 179-182.

Demirkilic U, Kuralay E, Yenicesu M, Caglar K, Oz BS, Cingoz F, Gunay C, Yildirim V, Ceylan S, Arslan M, Vural A, Tatar H: Timing of replacement therapy for acute renal failure after cardiac surgery. J Card Surg 2004, 19: 17-20. 10.1111/j.0886-0440.2004.04004.x

Elahi M, Asopa S, Pflueger A, Hakim N, Matata B: Acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery: impact of early versus late haemofiltration on morbidity and mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009, 35: 854-863. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.12.019

Gettings LG, Reynolds HN, Scalea T: Outcome in post-traumatic acute renal failure when continuous renal replacement therapy is applied early vs. late. Intensive Care Med 1999, 25: 805-813. 10.1007/s001340050956

Kennedy AC, Luke RG, Linton AL, Eaton JC, Gray MJ: Results of haemodialysis in severe acute tubular necrosis. A report of fifty-seven cases. Scott Med J 1963, 8: 97-108.

Kleinknecht D, Jungers P, Chanard J, Barbanel C, Ganeval D: Uremic and non-uremic complications in acute renal failure: Evaluation of early and frequent dialysis on prognosis. Kidney Int 1972, 1: 190-196. 10.1038/ki.1972.26

Kornhall S: Acute renal failure in surgical disease with special regard to neglected complications. A retrospective study of 298 cases treated during the period 1960-1968. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1971, 419: 3-64.

Kresse S, Schlee H, Deuber HJ, Koall W, Osten B: Influence of renal replacement therapy on outcome of patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl 1999, S75-78. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.56.s72.7.x

Lange HW, Aeppli DM, Brown DC: Survival of patients with acute renal failure requiring dialysis after open heart surgery: early prognostic indicators. Am Heart J 1987, 113: 1138-1143. 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90925-2

Liu KD, Himmelfarb J, Paganini E, Ikizler TA, Soroko SH, Mehta RL, Chertow GM: Timing of initiation of dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 1: 915-919. 10.2215/CJN.01430406

Parsons FM, Hobson SM, Blagg CR, McCracken BH: Optimum time for dialysis in acute reversible renal failure. Description and value of an improved dialyser with large surface area. Lancet 1961, 1: 129-134. 10.1016/S0140-6736(61)91309-5

Splendiani G, Mazzarella V, Cipriani S, Pollicita S, Rodio F, Casciani CU: Dialytic treatment of rhabdomyolysis-induced acute renal failure: our experience. Ren Fail 2001, 23: 183-191. 10.1081/JDI-100103490

Gibney RT, Bagshaw SM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Johnston C: When should renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury be initiated and discontinued? Blood Purif 2008, 26: 473-484. 10.1159/000157325

Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Levin A, Molitoris BA, Warnock DG, Shah SV, Joannidis M, Ronco C: Development of a clinical research agenda for acute kidney injury using an international, interdisciplinary, three-step modified Delphi process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008, 3: 887-894. 10.2215/CJN.04891107

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D: The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009, 6: e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

Kellum JA, Angus DC, Johnson JP, Leblanc M, Griffin M, Ramakrishnan N, Linde-Zwirble WT: Continuous versus intermittent renal replacement therapy: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28: 29-37. 10.1007/s00134-001-1159-4

Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, Grey A, MacLennan GS, Gamble GD, Reid IR: Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 341: c3691. 10.1136/bmj.c3691

Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002, 21: 1539-1558. 10.1002/sim.1186

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315: 629-634.

Sugahara S, Suzuki H: Early start on continuous hemodialysis therapy improves survival rate in patients with acute renal failure following coronary bypass surgery. Hemodial Int 2004, 8: 320-325. 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2004.80404.x

Sabater J, Perez XL, Albertos R, Gutierrez D, Labad X: Acute renal failure in septic shock. Should we consider different continuous renal replacement therapies on each RIFLE score stage? Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: S239.

Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Ronco C, Kellum JA: Timing of renal replacement therapy and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury. J Crit Care 2009, 24: 129-140. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.12.017

Bagshaw SM, Wald R, Barton J, Burns K, Friedrich JO, House AA, James MT, Levin A, Moist L, Pannu N, Stollery DE, Walsh MW: Initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury - a prospective multi-centre observational study [abstract]. Submitted to the 2010 AKI Critical Care Nephrology Conference, Edmonton, Canada; 2010.

Andrade L, Cleto S, Seguro A: Door-to-dialysis time and daily hemodialysis in patients with leptospirosis: impact on mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 2: 739-744. 10.2215/CJN.00680207

Carl DE, Grossman C, Behnke M, Sessler CN, Gehr TW: Effect of timing of dialysis on mortality in critically ill, septic patients with acute renal failure. Hemodial Int 2010, 14: 11-17. 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00407.x

Elahi MM, Lim MY, Joseph RN, Dhannapuneni RR, Spyt TJ: Early hemofiltration improves survival in post-cardiotomy patients with acute renal failure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004, 26: 1027-1031. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.07.039

Iyem H, Tavli M, Akcicek F, Buket S: Importance of early dialysis for acute renal failure after an open-heart surgery. Hemodial Int 2009, 13: 55-61. 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00347.x

Manche A, Casha A, Rychter J, Farrugia E, Debono M: Early dialysis in acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008, 7: 829-832. 10.1510/icvts.2008.181909

Shiao CC, Wu VC, Li WY, Lin YF, Hu FC, Young GH, Kuo CC, Kao TW, Huang DM, Chen YM, Tsai PR, Lin SL, Chou NK, Lin TH, Yeh YC, Wang CH, Chou A, Ko WJ, Wu KD: Late initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with worse outcomes in acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery. Crit Care 2009, 13: R171. 10.1186/cc8147

Wu VC, Ko WJ, Chang HW, Chen YS, Chen YW, Chen YM, Hu FC, Lin YH, Tsai PR, Wu KD: Early renal replacement therapy in patients with postoperative acute liver failure associated with acute renal failure: effect on postoperative outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2007, 205: 266-276. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.04.006

Seabra VF, Balk EM, Liangos O, Sosa MA, Cendoroglo M, Jaber BL: Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation in acute renal failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2008, 52: 272-284. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.371

Durmaz I, Yagdi T, Calkavur T, Mahmudov R, Apaydin AZ, Posacioglu H, Atay Y, Engin C: Prophylactic dialysis in patients with renal dysfunction undergoing on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2003, 75: 859-864. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04635-0

Payen D, Mateo J, Cavaillon JM, Fraisse F, Floriot C, Vicaut E: Impact of continuous venovenous hemofiltration on organ failure during the early phase of severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 803-810. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181962316

Piccinni P, Dan M, Barbacini S, Carraro R, Lieta E, Marafon S, Zamperetti N, Brendolan A, D'Intini V, Tetta C, Bellomo R, Ronco C: Early isovolaemic haemofiltration in oliguric patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 80-86. 10.1007/s00134-005-2815-x

Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, Ray JG: Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA 2009, 302: 1179-1185. 10.1001/jama.2009.1322

Bagshaw SM, George C, Bellomo R: Changes in the incidence and outcome for early acute kidney injury in a cohort of Australian intensive care units. Crit Care 2007, 11: R68. 10.1186/cc5949

Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, Lo S, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Myburgh J, Norton R, Scheinkestel C, Su S: Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2009, 361: 1627-1638. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902413

Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, O'Connor TZ, Chertow GM, Crowley ST, Choudhury D, Finkel K, Kellum JA, Paganini E, Schein RM, Smith MW, Swanson KM, Thompson BT, Vijayan A, Watnick S, Star RA, Peduzzi P: Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med 2008, 359: 7-20. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802639

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Michael Stoto and Shenaz Alidina for advice on study design.

This work was performed at the University of Alberta and the Harvard School of Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CJK carried out primary study search, extracted data, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. MF carried out the primary study search, extracted data, performed statistical analysis and tabulated quality indicators of the studies. IS and SM carried out the primary study search and extracted data. AL carried out statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript. RW helped draft/revise the manuscript. SMB conceived the idea, participated in its design and coordination and drafted/revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2010_9338_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional File 1: The PRISMA checklist. Summary of the completed checklist of quality measures for reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. (DOC 59 KB)

13054_2010_9338_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional File 2: Summary of search strategy. Detailed summary of search terms and strategy used for systematic literature search. (DOC 24 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Karvellas, C.J., Farhat, M.R., Sajjad, I. et al. A comparison of early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 15, R72 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10061

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10061