Abstract

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication in intensive care unit (ICU) patients and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. We compared long-term outcome and quality of life (QOL) in ICU patients with AKI treated with renal replacement therapy (RRT) with matched non-AKI-RRT patients.

Methods

Over 1 year, consecutive adult ICU patients were included in a prospective cohort study. AKI-RRT patients alive at 1 year and 4 years were matched with non-AKI-RRT survivors from the same cohort in a 1:2 (1 year) and 1:1 (4 years) ratio based on gender, age, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, and admission category. QOL was assessed by the EuroQoL-5D and the Short Form-36 survey before ICU admission and at 3 months, 1 and 4 years after ICU discharge.

Results

Of 1953 patients, 121 (6.2 %) had AKI-RRT. AKI-RRT hospital survivors (44.6 %; N = 54) had a 1-year and 4-year survival rate of 87.0 % (N = 47) and 64.8 % (N = 35), respectively. Forty-seven 1-year AKI-RRT patients were matched with 94 1-year non-AKI-RRT patients. Of 35 4-year survivors, three refused further cooperation, three were lost to follow-up, and one had no control. Finally, 28 4-year AKI-RRT patients were matched with 28 non-AKI-RRT patients. During ICU stay, 1-year and 4-year AKI-RRT patients had more organ dysfunction compared to their respective matches (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores 7 versus 5, P < 0.001, and 7 versus 4, P < 0.001). Long-term QOL was, however, comparable between both groups but lower than in the general population. QOL decreased at 3 months, improved after 1 and 4 years but remained under baseline level. One and 4 years after ICU discharge, 19.1 % and 28.6 % of AKI-RRT survivors remained RRT-dependent, respectively, and 81.8 % and 71 % of them were willing to undergo ICU admission again if needed.

Conclusion

In long-term critically ill AKI-RRT survivors, QOL was comparable to matched long-term critically ill non-AKI-RRT survivors, but lower than in the general population. The majority of AKI-RRT patients wanted to be readmitted to the ICU when needed, despite a higher severity of illness compared to matched non-AKI-RRT patients, and despite the fact that one quarter had persistent dialysis dependency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) treated with renal replacement therapy (RRT) affects approximately 5–10 % of intensive care unit (ICU) patients [1]. These patients are amongst the most severely ill patients in the ICU, as illustrated by the 50 % in-hospital mortality [2–4]. AKI-RRT patients who survive may develop chronic kidney disease, including end-stage renal disease, and experience decreased long-term survival [4–8]. Therefore, to fully appreciate outcomes of critically ill AKI-RRT survivors, indices regarding long-term morbidity and quality of life (QOL) should also be taken into account [9, 10].

Major reductions in long-term QOL in critically ill patients are seen in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, prolonged mechanical ventilation, severe sepsis, and after major trauma, all conditions frequently associated with AKI-RRT [11]. Data regarding QOL in AKI-RRT patients show that these patients have a decreased QOL compared to the general population but perceive QOL as good [12, 13]. However, these studies were either retrospective [14–17], evaluated QOL after a short term [12–15, 17–21], lacked baseline QOL assessment [12–15, 18, 22], or dated back more than a decade [14–16, 18, 23]. It is also unclear whether impairment in long-term QOL is the consequences of critical illness, AKI-RRT, pre-existing co-morbidities, or a combination of these.

The aim of the present study was to assess long-term outcomes and QOL of critically ill AKI-RRT patients at baseline, and at 3 months, 1 year and 4 years after ICU discharge and to compare QOL with a cohort of matched non-AKI-RRT patients [24].

Methods

Design, patients, and setting

The cohort described in this study is a subgroup of a prospective observational cohort. During one year (March 2008 to March 2009), all consecutively admitted adult patients at the 14-bed medical ICU (MICU), the 22-bed surgical ICU (SICU), and the 6-bed burns unit of the Ghent University Hospital, Belgium, were screened to study QOL and cost-effectiveness of intensive care [25]. Exclusion criteria were age <16 years and admission to the ICU after cardiac surgery. In case of multiple ICU admissions, only the first was considered.

In this study, only AKI-RRT patients of the larger cohort were included. Chronic hemodialysis patients were excluded. The attending critical care physician and consulting nephrologist assessed indication for RRT and modality.

To study the impact of RRT on long-term outcome and QOL, we performed a matched cohort study, according to the STROBE guidelines [26]. Included AKI-RRT patients alive at 1 year after hospital discharge were defined as exposed patients and individually matched with 1-year non-AKI-RRT survivors (defined as nonexposed patients) from the same cohort. Being a patient in the non-AKI-RRT group did not imply normal kidney function: it implied no treatment with RRT. To correct for possible bias, we excluded patients who needed RRT but who did not receive RRT due to therapeutic restrictions. Equally, AKI-RRT patients alive at time of this study (average 4 years later) were individually matched with 4-year non-AKI-RRT survivors. The exposed to nonexposed ratio was aimed at 1:2 to reduce risk of selection bias. When there were more than two nonexposed patients for an exposed patient, only the nonexposed patient with the best overall match was selected. If an exposed patient could only be properly matched to one nonexposed patient, we accepted matching in a 1:1 ratio for the respective cohort in order to avoid an imbalance of characteristics and to retain the best possible matching. Matching was based on gender, age (±5 years), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (±5), and admission category.

Data collection and definitions

Variables collected within the first 24 hours of ICU admission included age, gender, body mass index, personal, proxy, and family practitioner contact data, living situation, activity of daily living, co-morbidity as measured by the Charlson co-morbidity index [27], hospitalization in the last 6 months, main reason for ICU admission, APACHE II score [28], Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [29], need for mechanical ventilation, use of any vasopressors, and need for RRT. During ICU stay, SOFA scores, need for mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, RRT, and do-not-resuscitate codes were collected on a daily base. ICU length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and vital status at ICU and hospital discharge, and at 3 months, 1 year and 4 years following ICU discharge, were collected for each patient.

Values of serum creatinine for AKI-RRT patients were extracted from the STARRT database, which includes all relevant renal and RRT data of ICU patients with AKI-RRT treated in our hospital, and from laboratory data in control patients. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula [30]. Renal recovery was defined as independence from RRT.

The study was approved by the local ethical committee (Ethisch Comité Ghent University Hospital; amendment project 2007/423 approved 19 February 2013; B67020072805), and conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. A signed informed consent was obtained from every included patient.

Quality of life

QOL was assessed by means of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36v2®) and the EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D). The SF-36 questionnaire contains 36 items measuring eight health domains: physical (PF) and social functioning (SF), role limitations due to physical (RP) or emotional problems (RE), mental health (MH), vitality (VT), bodily pain (BP), and general perception of health (GH) [31]. Two component scores, a physical (PCS) and a mental (MCS), are calculated summary scores where, respectively, the physical domains (PF, RP, BP, GH) or the mental domains (VT, SF, RE, MH) will account more in the score. We assessed SF-36 as norm-based scores to be able to compare them directly with the general healthy population, with a group level range of 47–53 considered as average or normal [31]. Group scores less than 47 indicate impaired functioning within that health domain; group scores greater than or equal to 53 should be considered average or above the normative sample.

The 36th item, health transition, provides information about perceived changes in health status. The validity and reliability of the SF-36 has been confirmed in critically ill patients, and its use is validated in face-to-face interviews, telephone interview, and questionnaire by regular mail [32].

The EQ-5D is a generic QOL questionnaire that measures health in five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression [33]. Each dimension has three levels: no problems, moderate problems, or severe problems. On a visual analogue scale (VAS), patients can rate their perceived overall health between 0 and 100. The EQ-5D is suitable for measuring QOL in critical care [34, 35].

QOL was assessed at different time points: baseline QOL and strictly at 3 months and 1 year after ICU discharge. QOL was also assessed in August 2013, a median of 4.1 years (3.9–4.3 years) after ICU discharge. Following ICU admission and study inclusion, a face-to-face interview to assess baseline QOL (defined as QOL 2 weeks before ICU admission) was performed as soon as possible. This interview was preferably taken from the patient, or when impossible, from the proxy. Three months, 1 year, and 4 years after ICU discharge, patients were sent the EQ-5D and SF-36 surveys by regular mail; at 1 and 4 years, questions concerning living situation, memories, sleep quality, and willingness to be readmitted to an ICU department were added. If the questionnaires were not returned within 1 month, patients or relatives were contacted by phone to assess QOL after 1 year and after 4 years. Eventually, the family practitioner was contacted.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as median (interquartile range; IQR) for continuous variables and as number (%) for categorical variables. QOL at the different time points and characteristics between both groups (AKI-RRT versus non-AKI-RRT patients) were compared by the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and by the Chi-square test for categorical variables. For long-term analysis of QOL, differences between QOL at baseline (only hospital survivors), at 3 months and at 1 and 4 years after ICU discharge were assessed by Chi-square (EQ-5D) or Friedman test (SF-36). P values were two-sided and statistical significance was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were done using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 21 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

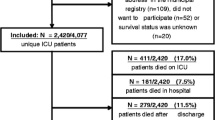

During the 1-year study period 1953 patients were included (Fig. 1). Of these, 147 patients (7.5 %) developed AKI with need for RRT. Of these, 121 patients (6.2 %) received RRT. ICU (46.3 %), hospital (55.4 %), 3-month (57.9 %), 1-year (61.1 %) and 4-year (71.1 %) mortality rates in these patients were high. Twenty-six AKI patients (1.3 %) did not receive RRT due to therapeutic restrictions and were excluded from further analysis.

AKI-RRT hospital survivors (44.6 %) had a 1-year and 4-year survival rate of 87.0 % and 64.8 %, respectively. Forty-seven 1-year AKI-RRT survivors were individually matched with 94 1-year non-AKI-RRT survivors (two matches for all AKI-RRT patients). Of 35 4-year survivors, three refused further cooperation, three were lost-to-follow-up, and one had a double match. In 13 of the 28 included 4-year AKI-RRT survivors, only one good match could be found, so matching occurred in a 1:1 ratio. Finally, 28 4-year AKI-RRT survivors were individually matched with 28 non-AKI-RRT patients. AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients had similar gender, age, APACHE II score, and admission category at 1 year and 4 years (Table 1).

During ICU stay, 1-year and 4-year AKI-RRT patients had higher SOFA scores compared to their respective matches, and more needed mechanical ventilation or vasopressors for a longer time (Table 1).

Renal characteristics and renal outcomes

One-year AKI-RRT patients had higher baseline serum creatinine concentrations and lower eGFR compared to their matches. These measurements did not significantly differ between 4-year AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients (Table 1).

Respectively, 12 1-year (25.5 %) and 10 4-year AKI-RRT patients (35.7 %) were RRT-dependent at hospital discharge. Nine (19.1 %) of the 1-year and 8 (28.6 %) of the 4-year AKI-RRT patients remained RRT dependent over time.

Quality of life

An overview of the persons who rated QOL, how QOL was assessed, and the number of completed QOL surveys is given in Table 2. Most patients rated their own QOL at the different time points, except at baseline in 1-year AKI-RRT patients.

Significant differences in QOL between AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT survivors at each different time point were small. Figures 2 and 3 show that the 1-year AKI-RRT versus 1-year non-AKI-RRT patients had comparable baseline QOL. The 1-year AKI-RRT patients were poorer emotionally at 3 months (RE 28.7 versus 38.4; P = 0.035), but had a better mental score (MCS 53.3 versus 47.8; P = 0.039) and less bodily pain (BP 46.5 versus 41.6; P = 0.041) at 1 year (Fig. 3). Figures 4 and 5 show that the 4-year AKI-RRT versus 4-year non-AKI-RRT patients were emotionally better at baseline (RE 55.9 versus 40.3; P = 0.030) (Fig. 5), but had more problems with usual activities (81.0 % versus 47.8 %; P = 0.023), pain (71.4 % versus 26.1 %; P = 0.003) and anxiety (61.9 % versus 17.4 %; P = 0.002) at 3 months (Fig. 4). QOL after 1 and 4 years showed no differences (Figs. 4 and 5).

EQ-5D assessments in the 1-year cohort. Percentages of patients with some or severe problems per dimension at the three different time points. The X-axis represents the different dimensions of the EQ-5D. The Y-axis represents the percentages (%) of patients with some or severe problems in a respective dimension. Only significant P values (Chi-Square test) are shown above the respective dimensions. AKI acute kidney injury, QOL quality of life, RRT renal replacement therapy

SF-36 assessments in the 1-year cohort. Norm-based median scores per domain at the three different time points. The X-axis represents the different domains of the SF-36. The Y-axis represents the norm-based median scores in a respective domain of the SF-36. A norm-based median score between 47 and 53 in a group of patients is considered as normal or average. Norm-based median scores below 47 indicate impaired functioning or below average; norm-based median scores above 53 indicate better functioning or above average. Only significant P values (Mann–Whitney U analysis) are shown above the respective domains. AKI acute kidney injury, BP bodily pain, GH general health, MCS mental component score, MH mental health, PCS physical component score, PF physical functioning, QOL quality of life, RE role emotional, RP role physical, RRT renal replacement therapy, SF social functioning, VT vitality

EQ-5D assessments in the 4-year cohort. Percentages of patients with some or severe problems per dimension at the four different time points. The X-axis represents the different dimensions of the EQ-5D. The Y-axis represents the percentages (%) of patients with some or severe problems in a respective dimension. Only significant P values (Chi Square test) are shown above the respective dimensions. AKI acute kidney injury, QOL quality of life, RRT renal replacement therapy

SF-36 assessments in the 4-year cohort. Norm-based median scores per domain at the four different time points. The X-axis represents the different domains of the SF-36. The Y-axis represents the norm-based median scores in a respective domain of the SF-36. A norm-based median score between 47 and 53 in a group of patients is considered as normal or average. Norm-based median scores below 47 indicate impaired functioning or below average; norm-based median scores above 53 indicate better functioning or above average. Only significant P values (Mann–Whitney U analysis) are shown above the respective domains. AKI acute kidney injury, BP bodily pain, GH general health, MCS mental component score, MH mental health, PCS physical component score, PF physical functioning, QOL quality of life, RE role emotional, RP role physical, RRT renal replacement therapy, SF social functioning, VT vitality

Comparing QOL within each group between the different time points revealed that QOL particularly decreased after 3 months.

Evolution in QOL over time: 1-year cohort

All 1-year AKI-RRT patients reported more problems on the EQ-5D after 3 months compared to baseline. After 1 year, they experienced fewer problems but still more than before ICU admission. The EQ-5D showed the same evolution for 1-year non-AKI-RRT patients (Additional file 1A and B).

The SF-36 showed significant evolutions in QOL over time for 1-year AKI-RRT patients in nearly all dimensions. QOL decreased after 3 months and improved after 1 year, but without return to the baseline level. QOL also remained under the level of the average population. The same pattern, although less pronounced, was seen in 1-year non-AKI-RRT patients (Additional file 2A and B).

For 1-year AKI-RRT patients the median VAS scores ranged from 70 (baseline), to 60 (3 months) and 70 (1 year) (P = 0.048). In non-AKI-RRT patients the VAS remained the same: 68, 65 and 65 at baseline, 3 months and 1 year after ICU discharge, respectively (P = 0.917).

Evolution in QOL over time: 4-year cohort

Changes in QOL over time assessed by the EQ-5D were significant in AKI-RRT patients for mobility (P = 0.040), usual activities (P < 0.001), and anxiety (P = 0.040) (Additional file 1C) and in 4-year non-AKI-RRT patients for mobility (P = 0.017), and usual activities (P = 0.014), with most problems at 3 months after ICU discharge followed by an improvement in QOL after 1 year (Additional file 1D). QOL never returned to baseline level.

The SF-36 showed that, in both groups, QOL decreased after 3 months compared to baseline (Additional file 2C and D). For the 4-year AKI-RRT patients, QOL improved after 1 year, especially in the mental domains. At 4 years, QOL significantly decreased physically but improved or remained the same in the mental components (Additional file 2C). Changes in long-term QOL in the 4-year non-AKI-RRT patients were less pronounced (Additional file 2D).

The 4-year AKI-RRT patients showed a decrease in VAS after 3 months (63), and improvements after 1 (70) and 4 years (68), but without regain of the baseline level (70) (P = 0.044). The 4-year non-AKI-RRT patients had the same evolution but without significance (P = 0.327).

Additional file 3 and Additional file 4 illustrate in more detail the variability in EQ-5D and SF-36 over time.

Overall, long-term QOL remained under the baseline level for AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients, and under the QOL of the average population.

Additional questions after 1 year and 4 years

One and 4 years after ICU discharge, most survivors lived independently, and only a minority stayed in a special care facility (Table 1). There were no major sleeping problems. One year and 4 years after ICU discharge, AKI-RRT patients had more bad memories than non-AKI-RRT patients (after 1 year, 17.4 % versus 4.3 %, P = 0.010; after 4 years, 21.4 % versus 3.8 %, P = 0.055). Of the 1-year AKI-RRT patients 81.8 % preferred to be readmitted to an ICU department in case of deterioration versus 83.0 % of their 1-year matches (P = 0.867). This number decreased to 71.4 % for the 4-year AKI-RRT patients versus 84.6 % for the 4-year non-AKI-RRT patients (P = 0.244).

Discussion

In this prospective, single-center matched cohort study concerning long-term outcomes and QOL of AKI-RRT patients, we found high mortality rates and lower QOL levels compared to the general population.

Similar to others, we found high hospital mortality (55 %) in this cohort of critically ill AKI-RRT patients, with only moderate increases in mortality at longer follow-up (58 % at 3 months, 61 % at 1 year, 71 % at 4 years) [4, 14, 15, 20, 36].

At hospital discharge and at long term, a quarter of AKI-RRT hospital survivors were RRT-dependent. These findings are similar to those reported in the literature [37].

Long-term survival data would be meaningless without considering QOL. Remarkably, there was no difference in QOL at different time points between AKI-RRT patients and matched non-AKI-RRT patients, although changes in QOL over time were less pronounced in the latter group. QOL decreased 3 months after ICU discharge compared to baseline, improved after 1 year, and stayed the same or improved slightly after 4 years, but still remained under baseline level.

The fact that long-term QOL had the same evolution over time in AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients was quite surprising suggesting that the AKI-RRT component during critical illness did not have an important impact on long-term QOL. Others reported very similar findings; however, these studies reported only on QOL after 6 months, and in one study not all AKI patients received RRT, and some patients received RRT without AKI [20, 21].

The fact that AKI-RRT patients were more severely ill during their ICU stay compared to matched patients had no influence on QOL over the years. This is in accordance with the findings of Orwelius et al. [38]. In a multicenter study they found that, 6 months after ICU discharge, perceived QOL in sepsis patients did not differ from ICU survivors with other diagnoses, even though these sepsis patients were more severely ill, and had a longer ICU stay. Another study by Orwelius suggested that long-term QOL was mainly affected by co-morbidity [39]. In our study AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients had a very comparable co-morbidity and medical history, which may explain the comparable long-term QOL between groups in our study.

QOL was perceived as acceptable and both AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients reported low dependence in daily life later on. The number of AKI-RRT and non-AKI-RRT patients who agreed to undergo life-sustaining interventions again in case of deterioration remained high. However, QOL was lower compared to that of the average population in both groups specifically in the more physical domains. This is in accordance with the findings of others [12–16, 20, 21].

Our study has several strengths. First, the matched cohort design demonstrates the real impact of AKI-RRT upon long-term QOL. This has not been evaluated thus far. Second, QOL was assessed with validated questionnaires at baseline, which allows for the only reliable evaluation of QOL over time without recall or selection bias [11, 40]. Third, the additional questions and VAS score allowed evaluation of the patients’ perception of the ICU admission and the consequences of severe illness. Finally, most studies report QOL in AKI survivors as a short-term endpoint, while this study also provides data for a longer follow-up period. Strict time intervals of 3 months and 1 year after ICU discharge were respected in all patients. For long-term assessment of QOL, an arbitrary time point was chosen (August 2013) which was between 47 and 52 months after ICU discharge for all patients. Response rate was very high and only three patients were lost to follow-up.

Some limitations should also be mentioned. First, single-center data from a university hospital may not reflect general practice and may limit external validity of the data. Second, although 1-year and 4-year AKI-RRT patients were matched to non-AKI-RRT patients based on four criteria, we cannot exclude that matched patients had a different profile compared to AKI-RRT patients. Third, the study cohort is relatively small and may lack statistical power to detect differences among the QOL domains in our study patients. Fourth, medical decisions leading to ICU referral may have selected for patients with better prospects. Fifth, long-term QOL may also be modified by events happening to the patient after hospital discharge. These were not recorded in the present study.

Conclusions

We found high mortality rates in AKI-RRT patients. However, in long-term critically ill AKI-RRT survivors, QOL was comparable to matched long-term critically ill survivors without AKI-RRT, but lower than in the general population. The majority of AKI-RRT patients wanted to be readmitted to the ICU when needed, despite a higher severity of illness compared to matched non-AKI-RRT patients, and despite the fact that one quarter had persistent dialysis dependency.

Key messages

-

Long-term critically ill AKI-RRT survivors have comparable QOL to matched long-term critically ill survivors without RRT.

-

QOL in long-term AKI-RRT survivors is lower than in the general population.

-

AKI-RRT patients are more severely ill during their ICU stay compared to matched non-AKI-RRT patients.

-

The majority of long-term AKI-RRT survivors prefer to be readmitted to the ICU department in case of deterioration.

-

One quarter of long-term AKI-RRT survivors have persistent dialysis dependency.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- BP:

-

Bodily pain

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQoL-5D

- GH:

-

General health

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- MCS:

-

Mental component score

- MH:

-

Mental health

- MICU:

-

Medical intensive care unit

- PCS:

-

Physical component score

- PF:

-

Physical functioning

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RE:

-

Role emotional

- RP:

-

Role physical

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- SF:

-

Social functioning

- SF-36:

-

Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey

- SICU:

-

Surgical intensive care unit

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- VT:

-

Vitality

References

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig S, Morimatsu H, Schetz M, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2005;294:813–8.

Hoste EA, Schurgers M. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury: how big is the problem? Crit Care Med. 2008;36:146–51.

Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, O’Connor TZ, Chertow GM, Crowley ST, Choudhury D, et al. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:7–20.

Bellomo R, Cass A, Norton R, Gallagher M, Lo S, Su S, et al. Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1627–38.

Amdur RL, Chawla LS, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. Outcomes following diagnosis of acute renal failure in U.S. veterans: focus on acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int. 2009;76:1089–97.

Ishani A, Xue JL, Himmelfarb J, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Molitoris BA, et al. Acute kidney injury increases risk of ESRD among elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:223–8.

Gammelager H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, Tonnesen E, Jespersen B, Sorensen HT. One-year mortality among Danish intensive care patients with acute kidney injury: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R124.

Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:58–66.

Mehlhron J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, Brunkhorst FM, Graf J, Troitzsch U, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintesive care unit syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1263–71.

Oeyen S, Vandijck D, Benoit D, Decruyenaere J, Annemans L, Hoste E. Long-term outcome after acute kidney injury in critically-ill patients. Acta Clin Belg. 2007;62:337–40.

Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, Annemans L, Decruynaere JM. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2386–400.

Ahlstrom A, Tallgren M, Peltonen S, Rasanen P, Pettila V. Survival and quality of life of patients requiring acute renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1222–8.

Delannoy B, Floccard B, Thiolliere F, Kaaki M, Badet M, Rosselli S, et al. Six-month outcome in acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy in the ICU: a multicentre prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1907–15.

Morgera S, Kraft AK, Siebert G, Luft FC, Neumayer HH. Long-term outcomes in acute renal failure patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:275–9.

Korkeila M, Ruokonen E, Takala J. Costs of care, long-term prognosis and quality of life in patients requiring renal replacement therapy during intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1824–31.

Gopal I, Bhonagiri S, Ronco C, Bellomo R. Out of hospital outcome and quality of life in survivors of combined acute multiple organ and renal failure treated with continuous venovenous hemofiltration/hemodiafiltration. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:766–72.

Abelha FJ, Botelho M, Fernandes V, Barros H. Outcome and quality of life of patients with acute kidney injury after major surgery. Nefrologia. 2009;29:404–14.

Maynard SE, Whittle J, Chelluri L, Arnold R. Quality of life and dialysis decisions in critically ill patients with acute renal failure. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1589–93.

Morsch C, Thome FS, Balbinotto A, Guimaraes JF, Barros EG. Health-related quality of life and dialysis dependence in critically ill patient survivors of acute kidney injury. Ren Fail. 2011;33:949–56.

Vaara ST, Pettila V, Reinikainen M, Kaukonen KM, Consortium FIC. Population-based incidence, mortality and quality of life in critically ill patients treated with renal replacement therapy: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Finnish intensive care units. Crit Care. 2012;16:R13.

Hofhuis JG, van Stel HF, Schrijvers AJ, Rommes JH, Spronk PE. The effect of acute kidney injury on long-term health-related quality of life: a prospective follow-up study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R17.

Noble JS, Simpson K, Allison ME. Long-term quality of life and hospital mortality in patients treated with intermittent or continuous hemodialysis for acute renal and respiratory failure. Ren Fail. 2006;28:323–30.

Hamel MB, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Desbiens N, Connors Jr AF, Teno JM, et al. Outcomes and cost-effectiveness of initiating dialysis and continuing aggressive care in seriously ill hospitalized adults. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:195–202.

De Corte W, Oeyen S, Annemans L, Benoit D, Dhondt A, Vanholder R, et al. Long-term outcome and quality of life in ICU patients with acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy: a case control study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40 (Suppl 1): 13.

Oeyen S, Benoit D, Annemans L, Decruyenaere J. Quality of life before, 3 months, and 1 year after ICU discharge. Crit Care Med. 2010;38 Suppl December:P587.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–35.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE, APACHE II. A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–10.

Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, Zhang YL, Beck GJ, Froissart M, et al. Comparative performance of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKI-EPI) and the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) study equations for estimating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:486–95.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B, Maruish ME. User’s Manual for the SF-36v2® Health Survey. Lincoln, Rhode Island: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007.

Chrispin PS, Scotton H, Rogers J, Lloyd D, Ridley SA. Short Form 36 in the intensive care unit: assessment of acceptability, reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:15–23.

Group EQ. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Brazier J, Jones N, Kind P. Testing the validity of the Euroqol and comparing it with the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:169–80.

Angus DC, Carlet J, Brussels RP. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–77.

Palevsky PM. Renal support in acute kidney injury—how much is enough? N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1699–701.

Wald R, McArthur E, Adhikari NK, Bagshaw SM, Burns KE, Garg AX, et al. Changing incidence and outcomes following dialysis requiring acute kidney injury among critically ill adults: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:870–7.

Orwelius L, Lobo C, Teixeira Pinto A, Carneiro A, Costa-Pereira A, Granja C. Sepsis patients do not differ in health-related quality of life compared with other ICU patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:1201–5.

Orwelius L, Nordlund A, Nordlund P, Simonsson E, Backman C, Samuelsson A, et al. Pre-existing disease: the most important factor for health related quality of life long-term after critical illness: a prospective, longitudinal, multicentre trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R67.

Joyce VR, Smith MW, Johansen KL, Unruh ML, Siroka AM, O’Connor TZ, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality among survivors of AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1063–70.

Acknowledgements

The authors wishes to thank the study nurses Patrick De Baets, Patsy Priem, Jo Vandenbossche, and Daniella Van der Jeught for their tremendous help, motivation, and enthusiasm concerning inclusions, interviewing patients, and calling patients or relatives. The authors also thank Chris Danneels for his help in setting up the database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SO and WDC acquired, analyzed and interpreted data. They also performed statistical analyses. They both were involved in drafting the manuscript, and revised it several times critically. DB, LA, AD, and RV revised the manuscript critically and helped with correct interpretation of data. JDC made a major contribution to the design of the study and interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript critically. EH made a major contribution to the design of the study, helped and gave advice with the statistical analysis and with interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

DB and EH both have a Research Grant from the FWO, Brussels, Belgium (www.fwo.be).

Sandra Oeyen and Wouter De Corte are joint first authors.

Sandra Oeyen and Wouter De Corte contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

EQ-5D assessments over time. In this additional file, evolutions in EQ-5D assessments are described through figures in the 1-year cohort (47 AKI-RRT (A) and 94 non-AKI-RRT patients (B)) and in the 4-year cohort (28 AKI-RRT (C) patients and 28 non-AKI-RRT patients (D)). Percentages of patients with some or severe problems in the different dimensions of the EQ-5D are given over the different time points: baseline, 3 months and 1 year (1-year cohort) and baseline, 3 months, 1 year and 4 years (4-year cohort). (PDF 111 kb)

Additional file 2:

SF-36 assessments over time. In this additional file, evolutions in SF-36 assessments are described through figures in the 1-year cohort (47 AKI-RRT (A) and 94 non-AKI-RRT patients (B)) and in the 4-year cohort (28 AKI-RRT (C) patients and 28 non-AKI-RRT patients (D)). Percentages of patients with some or severe problems in the different domains of the SF-36 are given over the different time points: baseline, 3 months and 1 year (1-year cohort) and baseline, 3 months, 1 year and 4 years (4-year cohort). (PDF 126 kb)

Additional file 3:

Variability in EQ-5D. In this additional file, more detailed information is given regarding variability of the EQ-5D at the different time points in the 1-year cohort and 4-year cohort. Percentages and 95 % confidence intervals of patients with some or severe problems on the respective dimensions of the EQ-5D over time are given in a table. (PDF 60 kb)

Additional file 4:

Variability in SF-36. In this additional file, more detailed information is given regarding variability of the SF-36 at the different time points in the 1-year cohort and 4-year cohort. Median norm-based scores with interquartile ranges on the different domains of the SF-36 over time are given in a table. (PDF 81 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Oeyen, S., De Corte, W., Benoit, D. et al. Long-term quality of life in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury treated with renal replacement therapy: a matched cohort study. Crit Care 19, 289 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-1004-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-1004-8