Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a complex type III secretion system to inject the toxins ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells. This system is regulated by the exoenzyme S regulon and includes the transcriptional activator ExsA. Of the four toxins, ExoU is characterized as the major virulence factor responsible for alveolar epithelial injury in patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Virulent strains of P. aeruginosa possess the exoU gene, whereas non-virulent strains lack this particular gene. The mechanism of virulence for the exoU + genotype relies on the presence of a pathogenic gene cluster (PAPI-2) encoding exoU and its chaperone, spcU. The ExoU toxin has a patatin-like phospholipase domain in its N-terminal, exhibits phospholipase A2 activity, and requires a eukaryotic cell factor for activation. The C-terminal of ExoU has a ubiquitinylation mechanism of activation. This probably induces a structural change in enzymatic active sites required for phospholipase A2 activity. In P. aeruginosa clinical isolates, the exoU + genotype correlates with a fluoroquinolone resistance phenotype. Additionally, poor clinical outcomes have been observed in patients with pneumonia caused by exoU +-fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates. Therefore, the potential exists to improve clinical outcomes in patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia by identifying virulent and antimicrobial drug-resistant strains through exoU genotyping or ExoU protein phenotyping or both.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been identified as a major cause of nosocomial infections [1],[2]. P. aeruginosa is the most frequent Gram-negative pathogen to cause mortality of patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in intensive care units [3]-[5]. Better understanding of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis, and subsequent mortality, has been acquired by recent advances in knowledge regarding virulence mechanisms that lead to acute lung injury, bacteremia, and sepsis [6]. In common with other pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa possesses a virulence mechanism known as the type III secretion system (TTSS). The TTSS allows the injection of toxins into the cytosol of target eukaryocytes [7],[8]. The type III secretory (TTS) toxin, ExoU, has been characterized as a major virulence factor in acute lung injury [9],[10]. The genomic organization of the ExoU gene, enzymatic activity of the ExoU protein, and mechanism of cell death induced by ExoU translocation have all been investigated. Among the various phenotypes of P. aeruginosa isolates, the ExoU-positive phenotype is a major risk factor for poor clinical outcomes. A correlation between the antimicrobial characteristics of the bacterium and an exoU-positive genotype has also been reported in recent clinical studies [11],[12].

This review summarizes progress with respect to basic research conducted on the TTS toxin, ExoU, to date. We have covered its genomic organization and biochemistry and its ability to cause acute lung injury in people. Additionally, we will discuss the findings of recent studies on the association between ExoU and poor clinical outcome in patients.

ExoU as a major virulence factor

Isolates of P. aeruginosa show cytotoxicity in cultured epithelial cells and cause a high degree of acute lung injury in animal models of pneumonia [13]-[15]. Clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa display various genotypic and phenotypic variations that can affect the severity of an infection and its clinical outcome [9]. P. aeruginosa produces various exoproducts, among which exoenzyme S and its co-regulated proteins are candidates for cytotoxicity and acute lung injury in patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia (Table 1) [16]-[18]. In the 1990s, based on genomic homology with its counterparts in other Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa exoenzyme S was identified as the effector protein that was injected into host cells via the TTSS (Figure 1) [19]. TTSSs, which are used by most pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria, including Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, and P. aeruginosa, function as molecular syringes, directly delivering toxins into the cytosol of eukaryotic cells [20]. The translocated toxins modulate eukaryotic cell signaling, a process that eventually causes disease [21],[22].

Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. P. aeruginosa injects its four type III secretory toxins ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY directly into the cytosol of target eukaryocytes through the type III secretory apparatus. Translocated toxins are activated by specific eukaryotic cell cofactors. Following activation, ExoS shows ADP-ribosyltransferase acitivity, whereas ExoT shows ADP-ribosyltransferase and GTPase activating protein (GAP) activity. Activated ExoU has phospholipase A2 activity, and ExoY exhibits adenylate cyclase activity.

PA103 lacks the exoenzyme S gene (exoS) encoding the 49-kDa form of the toxin but possesses the exoenzyme T gene (exoT), which encodes the 53-kDa form. An isogenic mutant missing exoT was found to be cytotoxic to cultured epithelial cells and caused acute lung injury; therefore, it was concluded that neither ExoT nor ExoS was a major virulence factor for lung injury [18]. PA103 was found to secrete a unique unknown 74-kDa protein, the production of which was decreased when a transposon mutation in exsA was present. The gene encoding this protein was cloned, and a mutant lacking this protein was created in PA103. The isogenic mutant lacking the 74-kDa protein failed to cause acute lung injury in animal models [9]. This protein, regulated by ExsA, a transcriptional activator of P. aeruginosa TTSS, was designated ExoU [9],[23]. Along with other TTS toxins, such as ExoS and ExoT, ExoU is secreted through the TTSS and injected directly into the cytosol of targeted eukaryocytes. Clinical isolates with cytotoxic phenotypes in vitro were found to possess exoU, whereas non-cytotoxic isolates lacked exoU [24]. Additionally, cytotoxic clinical isolates secreting ExoU caused severe and acute epithelial injury in animal models of P. aeruginosa pneumonia (Figure 2) [24]. It was postulated that the ability of P. aeruginosa to cause acute lung epithelial injury and sepsis is strongly linked to TTS secretion of ExoU [10].

Alveolar epithelial injury caused by the ExoU cytotoxin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Cytotoxic P. aeruginosa in the respiratory airspace injects the ExoU cytotoxin into alveolar epithelial cells, destroys the integrity of lung epithelium, and disseminates into the systemic circulation, causing bacteremia and sepsis.

Genomic organization of ExoU

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was the first strain whose genome was completely sequenced in 2001 by the Pseudomonas Genome Project. A pathogenic gene cluster, the exoenzyme S regulon, encodes genes underlying the regulation, secretion, and translocation of the TTSS. In the exoenzyme S regulon, five operons (exsD–pscL, exsCBA, pscG–popD, popN–pcrR, and pscN–pscU) encode TTSS and translocation machinery. The exsCBA operon encodes the transcriptional activator protein ExsA, which regulates expression of exoenzyme S and co-regulated proteins. The PAO1 strain lacks exoU, whereas approximately 20% of clinical isolates possess exoU (Figure 3) [25]. The exoU gene was initially cloned from the PA103 strain, along with its cognate chaperone gene spcU [9]. The genomic organization of the ExoU-secreting clinical isolate PA14 was analyzed, and two insertional genomic islands, termed pathogenicity islands PAPI-1 and PAPI-2 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity island), were discovered (Figure 3) [26]. The 10.7-kb PAPI-2 region, which is probably derived via horizontal gene transfer, lies within the tRNA-Lys (PA0976.1) region (Figure 3); it encodes 14 open reading frames, including exoU, spcU, four transposases, one integrase, one acetyltransferase, and six hypothetical proteins. The exoU gene itself is 2,074 base pairs and encodes the 682 amino acid protein, ExoU [27] (Figure 3). Four nucleotides at the 3′ end, including the stop codon in exoU, overlap the start codon of the 324-base pair spcU gene, which encodes SpcU (137 amino acids). The promoter region of exoU has a binding motif (TXAAAAXA) for the transcriptional activator, ExsA [28],[29].

Genomic organization of PAPI-2 and exoU . Genomic organization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain, PAO1, is shown (upper left). PAO1 contains 5,570 open reading frames (ORFs) in its 6.3-Mb genome. The type III secretion regulatory region (25.5 kb), known as the exoenzyme S regulon, contains 36 genes in the five operons. Genes encoding the type III secretory toxins exoS, exoT, and exoY, but not exoU, are scattered throughout the genome. exoU is located in an insertional pathogenic gene cluster known as PAPI-2 [26],[30]. PAPI-2 has 14 ORFs, including exoU and spcU, in a 10.7-Kb region (upper right). exoU has an ORF of 2,074 base pairs and a promoter region with an ExsA binding motif (TAAAAAA) at -74 (lower middle). The primary sequence of ExoU is 682 amino acids and contains an N-terminal secretory leader sequence, which shares similarity with ExoS and ExoT, and a patatin-like phospholipase domain with a catalytic dyad (Ser142 and Asp344), and a C-terminal DUF885 domain associated with a proposed ubiquitin binding domain. The patatin-like domain of ExoU has a structure similar to cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), and patatin from plants. Red letters with highlighted backgrounds indicate a perfect match. Blue letters indicate a partial match for amino acid sequences among four PLA2 proteins. PAPI, Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity island.

Enzymatic action of ExoU

The N-terminal of ExoU starts at the secretory leader (MHIQS), the sequence of which is the same as the starter sequence for ExoS and ExoT. When ExoU was identified as a major virulence factor causing acute lung injury in 1997, little was known about its enzymatic mechanisms that were responsible for acute cell death. Analysis of the conserved domain of ExoU revealed a patatin-like domain, containing a glycine-rich nucleotide binding loop motif and a lipase motif with catalytically active serine and aspartate within its N-terminal primary sequence [31]. Patatin, a storage protein in potatoes, exhibits lipase activity and shares a catalytic dyad structure with mammalian phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Figures 3 and 4) [32]-[35]. The catalytic domains of ExoU align with those of patatin, human calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) and cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2) [36]. The predicted active sites for ExoU PLA2 activity are serine 142 (S142) and aspartate 344 (D344). Site-directional mutagenesis of the predicted catalytic residues (ExoUS142A or ExoUD344A) eliminated the cytotoxicity of PA103 [36],[37]. Inhibitors of iPLA2 and cPLA2, including bromoenol lactone (BEL), methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphate (MAFP), and arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3), reduced the cytotoxicity of PA103 in vitro. In the presence of a eukaryotic cell extract, recombinant ExoU displayed PLA2 and lysophospholipase (lysoPLA) activities (Figure 5); these activities were inhibited by cPLA2 or iPLA2 inhibitors [31],[38]. The site-directional PA103 mutants lacking PLA2 activity were tested by using an animal model of pneumonia. In PA103, either of the ExoUS142A or ExoUD344A mutations abolished virulence associated with acute lung injury and death. It was concluded that acute lung injury from cytotoxic P. aeruginosa is caused by the cytotoxic activity of the patatin-like phospholipase domain of ExoU.

Phylogenetic analysis of lipase domains in patatin-like phospholipases. The conserved domain of ExoU contains a patatin-like phospholipase motif. Patatin, a storage protein in potato tubers, cucumbers, and rubber latex, exhibits lipase activity and shares a catalytic dyad structure with mammalian phospholipase A2 (PLA2). The catalytic domains of ExoU align with those of patatin, human calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) and cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted by using ClustalW [39].

Phospholipase A 2 and lysopholipase A activity of activated ExoU. ExoU that is activated by eukaryotic cell cofactors after translocation into the eukaryotic cell cytosol demonstrates hydrolytic activity toward phospholipids via its phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and lysophospholipase (lysoPLA) activities.

ExoU displays serine acylhydrolase activity via a Ser/Asp catalytic dyad and can be classified as a group IV PLA2 member. A major characteristic of serine acylhydrolases, such as PLA2, PLA1, and lysoPLA, is their ability to perform multiple lipase reactions [40]. Recently, more patatin-like PLA2 proteins have been detected in various bacterial species [41]. It seems likely that bacteria use PLA2 as a defense mechanism against predatory eukaryocytes such as phagocytes and environmental amoeba. Its presence allows them to attack a target cell to obtain nutrition, thereby increasing their population [40]. ExoU can kill eukaryotic predators, such as the amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii [42],[43]. Intracellular expression of ExoU is cytotoxic to yeast, suggesting that fungi could be one of its potential targets [44]. In humans, P. aeruginosa targets phagocytic cells in the lungs and injects them with ExoU [45]-[47]. In an animal model of pneumonia, ExoU is produced during the early phase of infection; delaying exoU expression by as little as 3 hours enhanced bacterial clearance and survival of infected mice [48]. ExoU-mediated impairment of phagocytes probably allows P. aeruginosa to persist within the lungs, causing localized immunosuppression and facilitating superinfection with less pathogenic bacteria. This would explain not only why ExoU-secreting P. aeruginosa is associated with more severe pulmonary infections but also the tendency of hospital-acquired pneumonia to be polymicrobial [47].

ExoU cytotoxicity and its various effects

Non-cytotoxic P. aeruginosa strains transformed with pUCP19exoUspcU, a plasmid that carries exoU and spcU, became cytotoxic to cultured epithelial cells in vitro and lethal in a mouse model of pneumonia [49]. Isogenic mutants, generated to secrete ExoU, ExoS, or ExoT, were evaluated for their relative contributions to pathogenesis in a mouse model of acute pneumonia [50]. In this study, measurements of mortality, bacterial persistence in the lungs, and dissemination of the bacteria indicated that ExoU secretion had the greatest impact on virulence but that secretion of ExoS had a moderate effect and ExoT a relatively minor effect.

ExoU translocation induces cell death by destroying cell membranes via PLA2 activity. ExoU might also contribute to the induction of an eicosanoid-mediated inflammatory response in host organisms, as airway epithelial cells exposed to P. aeruginosa overproduce prostaglandin E2 in an ExoU-dependent manner [51],[52]. A deleterious effect on phospholipid metabolism, in concert with caspase activation, was also reported to occur in an ExoU-dependent manner [53]. Another study reported that arachidonic acid-induced oxidative stress might cause cell damage during the course of an ExoU-producing P. aeruginosa infection. This is because endothelial cell death in cytotoxic PA103 infections was significantly attenuated by alpha-tocopherol [54]. ExoU could also contribute to the pathogenesis of lung injury as it induces a tissue factor-dependent procoagulant activity in airway epithelial cells [55], vascular hyperpermeability, platelet activation, and thrombus formation during P. aeruginosa pneumonia and sepsis [56].

Activation mechanism of ExoU

TTS toxins use a unique mechanism for activating their enzymatic activities. These toxins are initially produced in the bacterial cytosol as inactive forms and, immediately after being injected into the cytosol of a target eukaryotic cell by the bacterial secretion apparatus, are activated by specific eukaryotic cell cofactors. As an example, ExoS ADP-ribosyltransferase activity is activated by the eukaryotic protein factor FAS (factor activating exoenzyme S), which is a member of the 14-3-3 protein family [57],[58]. In contrast, P. aeruginosa adenylate cyclase ExoY requires an unknown eukaryotic cell factor for its activation [59]. The PLA2 activity of ExoU cleaves plasma membrane phospholipids and causes the rapid lysis of targeted eukaryotic cells. Similar to ExoS and ExoY, ExoU requires eukaryotic cell cofactors for its activation, whereas in vitro PLA2 assays with recombinant ExoU require the addition of eukaryotic cell lysates. The patatin-like PLA2 domain is located at the N-terminal region of ExoU; the C-terminal region, which includes a sequence corresponding to a conserved DUF885 domain, was reported to be important for the activation process and membrane localization of the protein [60]-[62]. In 2006, Sato and colleagues [63] reported that Cu2+, Zn2+-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) was a cofactor that activated the PLA2 activity of ExoU. By this time, however, it had also been reported that ExoU localizes to the plasma membrane, where it undergoes modification in the cell by the addition of two ubiquitin molecules at lysine 178; five C-terminal residues (679 to 683) control membrane localization and ubiquitination [64]. Site-directed spin-labeling electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy revealed that the addition of SOD1 induced conformational changes in ExoU [65]. PLA2 activity of ExoU was demonstrated by using ubiquitinated yeast SOD1 and other ubiquitinated mammalian proteins [66]. Therefore, it seems that ubiquitinated SOD1 works as a ubiquitin donor and that ubiquitination of the ExoU C-terminal activates the PLA2 activity of ExoU.

The three-dimensional crystallographic structure of ExoU combined with its cognate chaperone SpcU was recently elucidated by two research groups [67],[68] (Figure 6). In one of these studies, the C-terminal membrane-binding domain of ExoU displayed specificity for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5P2); ubiquitination of ExoU resulted in its co-localization with endosomal markers [67]. The ubiquitin-binding domain was mapped to a C-terminal four-helix bundle in ExoU [69], with PI4,5P2 synergistically enhancing the PLA2 activity of ExoU via a ubiquitin-related mechanism [70] (Figure 6). The Rickettsia prowazekii RP534 protein, a homologue of ExoU, possesses PLA2 and lysoPLA activities and PLA1 activity in the absence of any eukaryotic cofactors [71]. A structural comparison between ExoU and RP534 protein would help clarify the ubiquitin-associated mechanism of ExoU activation. Research into the mechanisms of ExoU activation has provided new insights into how bacteria manipulate eukaryotic cell signaling to facilitate their growth and pathogenesis.

Three-dimensional structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU. Left: position at 0; right: position horizontally rotated −180°. The phospholipase A2 catalytic dyad comprises S142 and D344. Loop structures such as the K178 area, S329-D344, G439-F444, and Y619-R682 seem to affect the structure of the catalytic dyad. The proposed ubiquitin-binding domain at the C-terminal of ExoU might comprise a pocket structure from these loops. Images of three-dimensional structures were generated by using the protein structure prediction server RaptorX [72].

Clinical epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosatype III secretory-associated genotypes

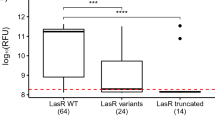

Early studies on P. aeruginosa TTSS revealed an association between a cytotoxic or invasive phenotype and genotype of a strain. The invasive PAO1 strain and the cytotoxic PA103 strain harbor the exoS +exoT +exoU − and exoS −exoT +exoU + genotypes, respectively [9],[18]. This genetic variation in TTS toxin genes implies the presence of similar genotypic and phenotypic variations among clinical and environmental isolates [73]. Consequently, isolates from the respiratory tract or blood cultures of 108 patients were analyzed, and the relative risk of mortality was reported to be sixfold greater when expression of ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, or PcrV occurred (Table 2). The prevalence of the TTS-positive phenotype was significantly higher in acutely infected patients than in chronically infected cystic fibrosis (CF) patients [24]. When Schulert and colleagues [74] analyzed the virulence profiles of 35 P. aeruginosa isolates from patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia by using a cytolytic cell-death assay, an apoptosis assay, and a mouse model of pneumonia, they found that increased virulence was associated with the secretion of ExoU but not ExoS or ExoY secretion. These studies suggest that P. aeruginosa TTSS is present in nearly all clinical and environmental isolates. ExoU secretion could be used as a marker for highly virulent strains and could have some association with poor clinical outcome. It appears that isolates from acutely infected patients are genotypically different from those from chronically infected CF patients [73]. Other researchers have reported the presence of different P. aeruginosa genotypes in isolates from CF patients. The exoS +exoU − genotype is associated with chronic infection in CF patients, whereas the exoS −exoU + genotype is associated with bacterial strains isolated from blood [75]-[79].

Clinical epidemiology associated with ExoU and antibiotic resistance

Another important topic in P. aeruginosa biology that has recently emerged is the association of antibiotic resistance with TTSS virulence genotypes (Table 2). Mitov and colleagues [85] analyzed the antimicrobial resistance profiles and genotypes of 202 isolates from CF patients (n = 42) and non-CF in-patients (n = 160). The authors found that the prevalences of exoS and exoU were 62.4 and 30.2%, respectively, and that exoU was more prevalent among MDR than in non-MDR strains (40.2% versus 17.7%). Garey and colleagues [81] reported that 97.5% of bloodstream isolates harbored exoS or exoU genes and that exoS was the most prevalent (70.5%; n = 86). The prevalence of exoU was 25.4% (n = 31), and these isolates were significantly more likely to be resistant to multiple antibiotics, including cephems, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and gentamicin. Consistent with this, an analysis of 45 clinical isolates found that exoU + isolates were more likely to be fluoroquinolone-resistant than exoS + isolates (92% versus 61%, P <0.05). These isolates possessed a mutation in the gyrA gene and exhibited an efflux pump overexpression phenotype [12]. Agnello and Wong-Beringer [82] examined the relationship between the TTSS effector genotype and fluoroquinolone resistance mechanisms in 270 respiratory isolates and found that a higher proportion of exoU + strains was fluoroquinolone-resistant compared with exoS + strains (63% versus 49%) despite their lower prevalence (38% exoU + versus 56% exoS +) [82]. Of epidemiological importance, Tran and colleagues [86] showed that 20 isolates (eight unique pulsed-field gel electrophoresis clusters) recovered from imported frozen raw shrimp sold in the US harbored TTS toxin genes and were resistant to quinolone with mutations in gyrA. These findings indicate co-evolution of resistance and virulence traits favoring a more virulent genotype in a quinolone-rich clinical environment [80].

There have been several studies in which associations between TTSS-associated virulence and poor clinical outcome for P. aeruginosa-infected patients have been observed. An analysis of TTS genotypes and phenotypes of isolates cultured from 35 mechanically ventilated patients with bronchoscopically confirmed P. aeruginosa-VAP showed a correlation between TTS phenotype, especially the ExoU phenotype, and severity of pneumonia [80]. More recently, El-Solh and colleagues [83] performed a retrospective analysis of 85 cases of P. aeruginosa bacteremia. Bacteremic patients with TTSS-positive isolates developed septic shock with high probability of death more frequently than patients with TTSS-negative isolates. The authors found that none of the TTSS-positive patients who survived the first 30 days of infection had a P. aeruginosa isolate that exhibited the ExoU phenotype; a higher frequency of antibiotic resistance was detected in TTSS-positive isolates. Jabalameli and colleagues [84] analyzed TTSS genotypes and antimicrobial resistance in 96 isolates collected from wound infections of burn patients. More than 90% of the isolates were MDR, and 64.5% of them carried exoU whereas 29% carried exoS. Their findings suggest that these genes, particularly exoU, are commonly disseminated among P. aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients. Sullivan and colleagues [11] recently reported their analysis of antimicrobial resistance and TTSS virulence in P. aeruginosa isolates from hospitalized adult patients with respiratory syndromes. The authors studied 218 consecutive adult patients whose respiratory cultures were positive for P. aeruginosa, and reported that fluoroquinolone-resistant and MDR strains were more likely to cause pneumonia than bronchitis or colonization. The combination of fluoroquinolone resistance and the gene encoding the TTSS ExoU effector in P. aeruginosa was the strongest predictor of pneumonia development. Further investigations suggest that the fluoroquinolone-resistant phenotype and the exoU + genotype of P. aeruginosa might cause poor clinical outcomes in patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia [87]. Although there is no clear genetic explanation and a less than convincing association between ExoU-associated virulence and antibiotic resistance, there is no doubt that bacterial strains possessing both virulent and MDR characteristics are more dangerous, especially for immunocompromised patients. Therefore, improved genotyping or phenotyping methods (or both) for analyzing TTS toxins of clinical isolates will enhance our understanding of this area.

Potential therapeutic strategies against ExoU-derived cytotoxicity

Several prophylactic or therapeutic experimental strategies against the cytotoxic effects of TTS ExoU have been reported over the last decade. The P. aeruginosa V-antigen PcrV, a homolog of the Yersinia V-antigen LcrV, contributes to TTS toxin translocation [88]. In prophylactic strategies, active immunization against PcrV ensures the survival of challenged mice and decreases lung inflammation and injury [89]. DNA vaccination with pIRES-toxAm-pcrV has been proposed as a potential immunotherapy [90]. In passive immunization, the rabbit polyclonal anti-PcrV antibody and murine monoclonal anti-PcrV antibody mAb166 inhibit TTS toxin translocation [91]-[95]. For clinical use, the mAb166 was humanized [96], and the IgG antigen-binding (Fab′) fragment, KB001, is currently in use in phase II clinical trials for treating VAP in France and chronic pneumonia in CF patients in the US [97],[98].

In vitro experiments have shown that specific inhibitors against iPLA2, such as BEL, AACOCF3, and MAFP, decrease the cytotoxicity of ExoU. Several researchers have reported that small molecules, such as pseudolipasin A and arylsulfonamides, specifically inhibit the phospholipase activity of ExoU [99],[100]. More details regarding the activation mechanisms of ExoU have been recently reported; however, there is more potential in using small chemicals for the prevention of acute lung injury induced by P. aeruginosa.

Conclusions

P. aeruginosa ExoU, a toxin injected into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells such as phagocytes and epithelial cells, is a major virulence factor in the cause of alveolar lung injury in patients with P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Virulent strains of P. aeruginosa possess the PAPI-2 pathogenic gene cluster region, which includes exoU. The PLA2 activity exhibited by ExoU requires a ubiquitination-associated activation mechanism to operate in a eukaryotic cell factor-dependent manner. A combination of the exoU + genotype and fluoroquinolone-resistant phenotype in isolates was shown to correlate with poor clinical outcome. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial-resistant P. aeruginosa is a serious concern, especially for immunocompromised patients. Therefore, rapid diagnostic determination of isolate genotype and phenotype is important. Surveillance to determine the prevalence of cytotoxic and antibiotic-resistant isolates is needed if we are to reduce the risk of lethal P. aeruginosa outbreaks. Opportunities exist for improving the clinical outcome of patients infected with P. aeruginosa by identifying virulent and antimicrobial-resistant isolates that cause acute lung injury, sepsis, and mortality. Exploration of P. aeruginosa virulence apparatuses as potential antimicrobial targets is vital if we are to avoid the spread of dangerous super-resistant P. aeruginosa strains.

Authors’ information

TS is a Professor of Anesthesiology. MS is a student in the Graduate School of Medicine at the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine in Japan. KM is an Associate Professor in the Anesthesia Department at Korin University in Japan. JWK is the Anesthetist-in-Chief (Henry Isaiah Dorr Professor of Anesthesia) at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA, USA).

Abbreviations

- AACOCF3:

-

Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone

- BEL:

-

Bromoenol lactone

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- cPLA2:

-

Cytosolic phospholipase A2

- iPLA2:

-

Calcium-independent phospholipase A2

- lysoPLA:

-

Lysophospholipase

- MAFP:

-

Methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphate

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- PAPI:

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity island

- PLA2:

-

Phospholipase A2

- SOD1:

-

Superoxide dismutase 1

- TTS:

-

Type III secretory

- TTSS:

-

Type III secretion system

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

References

Quartin AA, Scerpella EG, Puttagunta S, Kett DH: A comparison of microbiology and demographics among patients with healthcare-associated, hospital-acquired, and ventilator-associated pneumonia: a retrospective analysis of 1184 patients from a large, international study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013, 13: 561-10.1186/1471-2334-13-561.

Grgurich PE, Hudcova J, Lei Y, Sarwar A, Craven DE: Management and prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012, 6: 533-555. 10.1586/ers.12.45.

Barbier F, Andremont A, Wolff M, Bouadma L: Hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: recent advances in epidemiology and management. Curr Opinion Pulm Med. 2013, 19: 216-228. 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835f27be.

Bassetti M, Taramasso L, Giacobbe DR, Pelosi P: Management of ventilator-associated pneumonia: epidemiology, diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy. Expert Rev Anti-infective Ther. 2012, 10: 585-596. 10.1586/eri.12.36.

Sandiumenge A, Rello J: Ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by ESKAPE organisms: cause, clinical features, and management. Curr Opinion Pulm Med. 2012, 18: 187-193. 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328351f974.

Sawa T: The molecular mechanism of acute lung injury caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: from bacterial pathogenesis to host response. J Intensive Care. 2014, 2: 10-10.1186/2052-0492-2-10.

Engel J, Balachandran P: Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III effectors in disease. Curr Opinion Microbiol. 2009, 12: 61-66. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.12.007.

Hauser AR: The type III secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: infection by injection. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2009, 7: 654-665. 10.1038/nrmicro2199.

Finck-Barbancon V, Goranson J, Zhu L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Fleiszig SM, Wu C, Mende-Mueller L, Frank DW: ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Mol Microbiol. 1997, 25: 547-557. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4891851.x.

Kurahashi K, Kajikawa O, Sawa T, Ohara M, Gropper MA, Frank DW, Martin TR, Wiener-Kronish JP: Pathogenesis of septic shock in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Clin Invest. 1999, 104: 743-750. 10.1172/JCI7124.

Sullivan E, Bensman J, Lou M, Agnello M, Shriner K, Wong-Beringer A: Risk of developing pneumonia is enhanced by the combined traits of fluoroquinolone resistance and type III secretion virulence in respiratory isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Crit Care Med. 2014, 42: 48-56. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a86f.

Wong-Beringer A, Wiener-Kronish J, Lynch S, Flanagan J: Comparison of type III secretion system virulence among fluoroquinolone-susceptible and -resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008, 14: 330-336. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01939.x.

Wiener-Kronish JP, Sakuma T, Kudoh I, Pittet JF, Frank D, Dobbs L, Vasil ML, Matthay MA: Alveolar epithelial injury and pleural empyema in acute P. aeruginosa pneumonia in anesthetized rabbits. J Appl Physiol. 1993, 75: 1661-1669.

Kudoh I, Wiener-Kronish JP, Hashimoto S, Pittet JF, Frank D: Exoproduct secretions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains influence severity of alveolar epithelial injury. Am J Physiol. 1994, 267: L551-L556.

Wiener-Kronish JP, Broaddus VC, Albertine KH, Gropper MA, Matthay MA, Staub NC: Relationship of pleural effusions to increased permeability pulmonary edema in anesthetized sheep. J Clin Invest. 1988, 82: 1422-1429. 10.1172/JCI113747.

Nicas TI, Iglewski BH: Contribution of exoenzyme S to the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Antibiot Chemother. 1985, 36: 40-48.

Nicas TI, Iglewski BH: The contribution of exoproducts to virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Can J Microbiol. 1985, 31: 387-392. 10.1139/m85-074.

Fleiszig SM, Wiener-Kronish JP, Miyazaki H, Vallas V, Mostov KE, Kanada D, Sawa T, Yen TS, Frank DW: Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated cytotoxicity and invasion correlate with distinct genotypes at the loci encoding exoenzyme S. Infect Immun. 1997, 65: 579-586.

Yahr TL, Goranson J, Frank DW: Exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is secreted by a type III pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1996, 22: 991-1003. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01554.x.

Hueck CJ: Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998, 62: 379-433.

Galan JE, Collmer A: Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science. 1999, 284: 1322-1328. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322.

Lee CA: Type III secretion systems: machines to deliver bacterial proteins into eukaryotic cells?. Trends Microbiol. 1997, 5: 148-156. 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01029-9.

Frank DW: The exoenzyme S regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Mol Microbiol. 1997, 26: 621-629. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6251991.x.

Roy-Burman A, Savel RH, Racine S, Swanson BL, Revadigar NS, Fujimoto J, Sawa T, Frank DW, Wiener-Kronish JP: Type III protein secretion is associated with death in lower respiratory and systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Infect Dis. 2001, 183: 1767-1774. 10.1086/320737.

Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV: Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000, 406: 959-964. 10.1038/35023079.

He J, Baldini RL, Deziel E, Saucier M, Zhang Q, Liberati NT, Lee D, Urbach J, Goodman HM, Rahme LG: The broad host range pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 carries two pathogenicity islands harboring plant and animal virulence genes. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2004, 101: 2530-2535. 10.1073/pnas.0304622101.

Groisman EA, Ochman H: Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell. 1996, 87: 791-794. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81985-6.

Hovey AK, Frank DW: Analyses of the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation properties of ExsA, the transcriptional activator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J Bacteriol. 1995, 177: 4427-4436.

Goranson J, Frank DW: Genetic analysis of exoenzyme S expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996, 135: 149-155. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07981.x.

Kulasekara BR, Kulasekara HD, Wolfgang MC, Stevens L, Frank DW, Lory S: Acquisition and evolution of the exoU locus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol. 2006, 188: 4037-4050. 10.1128/JB.02000-05.

Sato H, Feix JB, Hillard CJ, Frank DW: Characterization of phospholipase activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III cytotoxin, ExoU. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187: 1192-1195. 10.1128/JB.187.3.1192-1195.2005.

Racusen D: Lipid acyl hydrolase of patatin. Can J Bot. 1984, 62: 1640-10.1139/b84-220.

Andrews DL, Beames B, Summers MD, Park WD: Characterization of the lipid acyl hydrolase activity of the major potato (Solanum tuberosum) tuber protein, patatin, by cloning and abundant expression in a baculovirus vector. Biochem J. 1988, 252: 199-206.

Senda K, Yoshioka H, Doke N, Kawakita K: A cytosolic phospholipase A 2from potato tissues appears to be patatin. Plant Cell Physiol 1996, 37:347–353.,

Hirschberg HJ, Simons JW, Dekker N, Egmond MR: Cloning, expression, purification and characterization of patatin, a novel phospholipase A. Eur J Biochem. 2001, 268: 5037-5044. 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02411.x.

Sato H, Frank DW, Hillard CJ, Feix JB, Pankhaniya RR, Moriyama K, Finck-Barbancon V, Buchaklian A, Lei M, Long RM, Wiener-Kronish J, Sawa T: The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. EMBO J. 2003, 22: 2959-2969. 10.1093/emboj/cdg290.

Phillips RM, Six DA, Dennis EA, Ghosh P: In vivo phospholipase activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU and protection of mammalian cells with phospholipase A 2inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:41326–41332.,

Tamura M, Ajayi T, Allmond LR, Moriyama K, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T: Lysophospholipase A activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretory toxin ExoU. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2004, 316: 323-331. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.050.

Multiple Sequence Alignment by CLUSTALW , [http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/]

Ghosh M, Tucker DE, Burchett SA, Leslie CC: Properties of the Group IV phospholipase A 2 family. Prog Lipid Res 2006, 45:487–510.,

Banerji S, Flieger A: Patatin-like proteins: a new family of lipolytic enzymes present in bacteria?. Microbiol. 2004, 150: 522-525. 10.1099/mic.0.26957-0.

Abd H, Wretlind B, Saeed A, Idsund E, Hultenby K, Sandstrom G: Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilises its type III secretion system to kill the free-living amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii . J Eukaryotic Microbiol. 2008, 55: 235-243. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00311.x.

Matz C, Moreno AM, Alhede M, Manefield M, Hauser AR, Givskov M, Kjelleberg S: Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses type III secretion system to kill biofilm-associated amoebae. ISME J. 2008, 2: 843-852. 10.1038/ismej.2008.47.

Rabin SD, Hauser AR: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU, a toxin transported by the type III secretion system, kills Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Infect Immun. 2003, 71: 4144-4150. 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4144-4150.2003.

Hauser AR, Engel JN: Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces type-III-secretion-mediated apoptosis of macrophages and epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999, 67: 5530-5537.

Diaz MH, Shaver CM, King JD, Musunuri S, Kazzaz JA, Hauser AR: Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces localized immunosuppression during pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2008, 76: 4414-4421. 10.1128/IAI.00012-08.

Diaz MH, Hauser AR: Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU is injected into phagocytic cells during acute pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2010, 78: 1447-1456. 10.1128/IAI.01134-09.

Howell HA, Logan LK, Hauser AR: Type III secretion of ExoU is critical during early Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. MBio. 2013, 4: e00032-00013. 10.1128/mBio.00032-13.

Allewelt M, Coleman FT, Grout M, Priebe GP, Pier GB: Acquisition of expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU cytotoxin leads to increased bacterial virulence in a murine model of acute pneumonia and systemic spread. Infect Immun. 2000, 68: 3998-4004. 10.1128/IAI.68.7.3998-4004.2000.

Shaver CM, Hauser AR: Relative contributions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU, ExoS, and ExoT to virulence in the lung. Infect Immun. 2004, 72: 6969-6977. 10.1128/IAI.72.12.6969-6977.2004.

Saliba AM, Nascimento DO, Silva MC, Assis MC, Gayer CR, Raymond B, Coelho MG, Marques EA, Touqui L, Albano RM, Lopes UG, Paiva DD, Bozza PT, Plotkowskiet MC: Eicosanoid-mediated proinflammatory activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU. Cellular Microbiol. 2005, 7: 1811-1822. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00635.x.

Plotkowski MC, Brandao BA, de Assis MC, Feliciano LF, Raymond B, Freitas C, Saliba AM, Zahm JM, Touqui L, Bozza PT: Lipid body mobilization in the ExoU-induced release of inflammatory mediators by airway epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. 2008, 45: 30-37. 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.01.008.

Henderson FC, Miakotina OL, Mallampalli RK: Proapoptotic effects of P. aeruginosa involve inhibition of surfactant phosphatidylcholine synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2006, 47: 2314-2324. 10.1194/jlr.M600284-JLR200.

Saliba AM, de Assis MC, Nishi R, Raymond B, Marques Ede A, Lopes UG, Touqui L, Plotkowski MC: Implications of oxidative stress in the cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8: 450-459. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.011.

Plotkowski MC, Feliciano LF, Machado GB, Cunha LG, Freitas C, Saliba AM, de Assis MC: ExoU-induced procoagulant activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected airway cells. Eur Respir J. 2008, 32: 1591-1598. 10.1183/09031936.00086708.

Machado GB, de Assis MC, Leao R, Saliba AM, Silva MC, Suassuna JH, de Oliveira AV, Plotkowski MC: ExoU-induced vascular hyperpermeability and platelet activation in the course of experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumosepsis. Shock. 2010, 33: 315-321. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b2b0f4.

Fu H, Coburn J, Collier RJ: The eukaryotic host factor that activates exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a member of the 14-3-3 protein family. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1993, 90: 2320-2324. 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2320.

Coburn J, Kane AV, Feig L, Gill DM: Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S requires a eukaryotic protein for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 1991, 266: 6438-6446.

Yahr TL, Vallis AJ, Hancock MK, Barbieri JT, Frank DW: ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95: 13899-13904. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13899.

Rabin SD, Hauser AR: Functional regions of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU. Infect Immun. 2005, 73: 573-582. 10.1128/IAI.73.1.573-582.2005.

Rabin SD, Veesenmeyer JL, Bieging KT, Hauser AR: A C-terminal domain targets the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU to the plasma membrane of host cells. Infect Immun. 2006, 74: 2552-2561. 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2552-2561.2006.

Veesenmeyer JL, Howell H, Halavaty AS, Ahrens S, Anderson WF, Hauser AR: Role of the membrane localization domain of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa effector protein ExoU in cytotoxicity. Infect Immun. 2010, 78: 3346-3357. 10.1128/IAI.00223-10.

Sato H, Feix JB, Frank DW: Identification of superoxide dismutase as a cofactor for the pseudomonas type III toxin, ExoU. Biochemistry. 2006, 45: 10368-10375. 10.1021/bi060788j.

Stirling FR, Cuzick A, Kelly SM, Oxley D, Evans TJ: Eukaryotic localization, activation and ubiquitinylation of a bacterial type III secreted toxin. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8: 1294-1309. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00710.x.

Benson MA, Komas SM, Schmalzer KM, Casey MS, Frank DW, Feix JB: Induced conformational changes in the activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III toxin, ExoU. Biophys J. 2011, 100: 1335-1343. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.056.

Anderson DM, Schmalzer KM, Sato H, Casey M, Terhune SS, Haas AL, Feix JB, Frank DW: Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-modified proteins activate the Pseudomonas aeruginosa T3SS cytotoxin, ExoU. Mol Microbiol. 2011, 82: 1454-1467. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07904.x.

Gendrin C, Contreras-Martel C, Bouillot S, Elsen S, Lemaire D, Skoufias DA, Huber P, Attree I, Dessen A: Structural basis of cytotoxicity mediated by the type III secretion toxin ExoU from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . PLoS Pathogens. 2012, 8: e1002637-10.1371/journal.ppat.1002637.

Halavaty AS, Borek D, Tyson GH, Veesenmeyer JL, Shuvalova L, Minasov G, Otwinowski Z, Hauser AR, Anderson WF: Structure of the type III secretion effector protein ExoU in complex with its chaperone SpcU. PloS One. 2012, 7: e49388-10.1371/journal.pone.0049388.

Anderson DM, Feix JB, Monroe AL, Peterson FC, Volkman BF, Haas AL, Frank DW: Identification of the major ubiquitin-binding domain of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU A 2 phospholipase. J Biol Chem 2013, 288:26741–26752.,

Tyson GH, Hauser AR: Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate is a novel coactivator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU. Infect Immun. 2013, 81: 2873-2881. 10.1128/IAI.00414-13.

Housley NA, Winkler HH, Audia JP: The Rickettsia prowazekii ExoU homologue possesses phospholipase A 1 (PLA 1 ), PLA 2 , and lyso-PLA 2 activities and can function in the absence of any eukaryotic cofactors in vitro. J Bacteriol 2011, 193:4634–4642.,

Xu Group: Protein structure and function prediction web service RaptorX , [http://raptorx.uchicago.edu]

Feltman H, Schulert G, Khan S, Jain M, Peterson L, Hauser AR: Prevalence of type III secretion genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Microbiol. 2001, 147: 2659-2669.

Schulert GS, Feltman H, Rabin SD, Martin CG, Battle SE, Rello J, Hauser AR: Secretion of the toxin ExoU is a marker for highly virulent Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates obtained from patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2003, 188: 1695-1706. 10.1086/379372.

Wareham DW, Curtis MA: A genotypic and phenotypic comparison of type III secretion profiles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis and bacteremia isolates. Int J Medl Microbiol. 2007, 297: 227-234. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.02.004.

Bradbury RS, Roddam LF, Merritt A, Reid DW, Champion AC: Virulence gene distribution in clinical, nosocomial and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59: 881-890. 10.1099/jmm.0.018283-0.

Tingpej P, Smith L, Rose B, Zhu H, Conibear T, Al Nassafi K, Manos J, Elkins M, Bye P, Willcox M, Bell S, Wainwright C, Harbour C: Phenotypic characterization of clonal and nonclonal Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from lungs of adults with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45: 1697-1704. 10.1128/JCM.02364-06.

Jain M, Ramirez D, Seshadri R, Cullina JF, Powers CA, Schulert GS, Bar-Meir M, Sullivan CL, McColley SA, Hauser AR: Type III secretion phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains change during infection of individuals with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 5229-5237. 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5229-5237.2004.

Hu H, Harmer C, Anuj S, Wainwright CE, Manos J, Cheney J, Harbour C, Zablotska I, Turnbull L, Whitchurch CB, Grimwood K, Rose B: Type 3 secretion system effector genotype and secretion phenotype of longitudinally collected Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from young children diagnosed with cystic fibrosis following newborn screening. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013, 19: 266-272. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03770.x.

Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Valles J, Engel JN, Rello J: Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Crit Care Med. 2002, 30: 521-528. 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00005.

Garey KW, Vo QP, Larocco MT, Gentry LO, Tam VH: Prevalence of type III secretion protein exoenzymes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from bloodstream isolates of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. J Chemother. 2008, 20: 714-720. 10.1179/joc.2008.20.6.714.

Agnello M, Wong-Beringer A: Differentiation in quinolone resistance by virulence genotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . PloS One. 2012, 7: e42973-10.1371/journal.pone.0042973.

El-Solh AA, Hattemer A, Hauser AR, Alhajhusain A, Vora H: Clinical outcomes of type III Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40: 1157-1163. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182377906.

Jabalameli F, Mirsalehian A, Khoramian B, Aligholi M, Khoramrooz SS, Asadollahi P, Taherikalani M, Emaneini M: Evaluation of biofilm production and characterization of genes encoding type III secretion system among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from burn patients. Burns. 2012, 38: 1192-1197. 10.1016/j.burns.2012.07.030.

Mitov I, Strateva T, Markova B: Prevalence of virulence genes among Bulgarian nosocomial and cystic fibrosis isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010, 41: 588-595. 10.1590/S1517-83822010000300008.

Tran QT, Nawaz MS, Deck J, Foley S, Nguyen K, Cerniglia CE: Detection of type III secretion system virulence and mutations in gyrA and parC genes among quinolone-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from imported shrimp. Foodborne Pathogens Dis. 2011, 8: 451-453. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0687.

Cho HH, Kwon KC, Kim S, Koo SH: Correlation between virulence genotype and fluoroquinolone resistance in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Ann Lab Med. 2014, 34: 286-292. 10.3343/alm.2014.34.4.286.

Sawa T, Katoh H, Yasumoto H: V-antigen homologs in pathogenic gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Immunol. 2014, 58: 267-285. 10.1111/1348-0421.12147.

Sawa T, Yahr TL, Ohara M, Kurahashi K, Gropper MA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Frank DW: Active and passive immunization with the Pseudomonas V antigen protects against type III intoxication and lung injury. Nat Med. 1999, 5: 392-398. 10.1038/7391.

Jiang M, Yao J, Feng G: Protective effect of DNA vaccine encoding pseudomonas exotoxin A and PcrV against acute pulmonary P. aeruginosa infection. PLoS One. 2014, 9: e96609-10.1371/journal.pone.0096609.

Shime N, Sawa T, Fujimoto J, Faure K, Allmond LR, Karaca T, Swanson BL, Spack EG, Wiener-Kronish JP: Therapeutic administration of anti-PcrV F(ab')(2) in sepsis associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Immunol. 2001, 167: 5880-5886. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5880.

Imamura Y, Yanagihara K, Fukuda Y, Kaneko Y, Seki M, Izumikawa K, Miyazaki Y, Hirakata Y, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Kohno S: Effect of anti-PcrV antibody in a murine chronic airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection model. Eur Respir J. 2007, 29: 965-968. 10.1183/09031936.00147406.

Frank DW, Vallis A, Wiener-Kronish JP, Roy-Burman A, Spack EG, Mullaney BP, Megdoud M, Marks JD, Fritz R, Sawa T: Generation and characterization of a protective monoclonal antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV. J Infect Dis. 2002, 186: 64-73. 10.1086/341069.

Faure K, Fujimoto J, Shimabukuro DW, Ajayi T, Shime N, Moriyama K, Spack EG, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T: Effects of monoclonal anti-PcrV antibody on Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury in a rat model. J Immune Based Ther Vaccines. 2003, 1: 2-10.1186/1476-8518-1-2.

Song Y, Baer M, Srinivasan R, Lima J, Yarranton G, Bebbington C, Lynch SV: PcrV antibody-antibiotic combination improves survival in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected mice. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012, 31: 1837-1845. 10.1007/s10096-011-1509-2.

Baer M, Sawa T, Flynn P, Luehrsen K, Martinez D, Wiener-Kronish JP, Yarranton G, Bebbington C: An engineered human antibody Fab fragment specific for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV antigen has potent anti-bacterial activity. Infect Immun. 2008, 77: 1083-1090. 10.1128/IAI.00815-08.

François B, Luyt CE, Dugard A, Wolff M, Diehl JL, Jaber S, Forel JM, Garot D, Kipnis E, Mebazaa A, Misset B, Andremont A, Ploy MC, Jacobs A, Yarranton G, Pearce T, Fagon JY, Chastre J: Safety and pharmacokinetics of an anti-PcrV PEGylated monoclonal antibody fragment in mechanically ventilated patients colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40: 2320-2326. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825334f6.

Milla CE, Chmiel JF, Accurso FJ, Vandevanter DR, Konstan MW, Yarranton G, Geller DE: Anti-PcrV antibody in cystic fibrosis: a novel approach targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014, 49: 650-658. 10.1002/ppul.22890.

Lee VT, Pukatzki S, Sato H, Kikawada E, Kazimirova AA, Huang J, Li X, Arm JP, Frank DW, Lory S: Pseudolipasin A is a specific inhibitor for phospholipase A2 activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU. Infect Immun. 2007, 75: 1089-1098. 10.1128/IAI.01184-06.

Kim D, Baek J, Song J, Byeon H, Min H, Min KH: Identification of arylsulfonamides as ExoU inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014, S0960-894X: 00692-1-

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI #24390403) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Japan) to TS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JPWK and TS have a patent for immunization with PcrV from the Regent of the University of California (Berkeley, CA, USA).

Authors’ contributions

TS wrote the manuscript, figure legends, and tables. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawa, T., Shimizu, M., Moriyama, K. et al. Association between Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion, antibiotic resistance, and clinical outcome: a review. Crit Care 18, 668 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0668-9

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0668-9