Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common gram-negative pathogen causing pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Acute lung injury induced by bacterial exoproducts is associated with a poor outcome in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. The major pathogenic toxins among the exoproducts of P. aeruginosa and the mechanism by which they cause acute lung injury have been investigated: exoenzyme S and co-regulated toxins were found to contribute to acute lung injury. P. aeruginosa secretes these toxins through the recently defined type III secretion system (TTSS), by which gram-negative bacteria directly translocate toxins into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells. TTSS comprises the secretion apparatus (termed the injectisome), translocators, secreted toxins, and regulatory components. In the P. aeruginosa genome, a pathogenic gene cluster, the exoenzyme S regulon, encodes genes underlying the regulation, secretion, and translocation of TTSS. Four type III secretory toxins, namely ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY, have been identified in P. aeruginosa. ExoS is a 49-kDa form of exoenzyme S, a bifunctional toxin that exerts ADP-ribosyltransferase and GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity to disrupt endocytosis, the actin cytoskeleton, and cell proliferation. ExoT, a 53-kDa form of exoenzyme S with 75% sequence homology to ExoS, also exerts GAP activity to interfere with cell morphology and motility. ExoY is a nucleotidal cyclase that increases the intracellular levels of cyclic adenosine and guanosine monophosphates, resulting in edema formation. ExoU, which exhibits phospholipase A2 activity activated by host cell ubiquitination after translocation, is a major pathogenic cytotoxin that causes alveolar epithelial injury and macrophage necrosis. Approximately 20% of clinical isolates also secrete ExoU, a gene encoded within an insertional pathogenic gene cluster named P. aeruginosa pathogenicity island-2. The ExoU secretory phenotype is associated with a poor clinical outcome in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Blockade of translocation by TTSS or inhibition of the enzymatic activity of translocated toxins has the potential to decrease acute lung injury and improve clinical outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most common gram-negative pathogens causing pneumonia in immunocompromised patients [1–4]. Ventilated patients are at particularly high risk of developing P. aeruginosa pneumonia [5, 6], and the mortality rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) due to P. aeruginosa is significantly higher than that due to other pathogens [7–9]. Some P. aeruginosa strains possess the ability to destroy the integrity of the alveolar epithelial barrier, causing rapid necrosis of the lung epithelium and bacterial dissemination into the circulation [10, 11]. Understanding the mechanism by which virulent strains of P. aeruginosa cause acute lung injury is critical for preventing subsequent sepsis and death. The present review summarizes the progress and explains the mechanisms causing acute lung injury and sepsis, focusing on the type III secretion system (TTSS) of P. aeruginosa.

Review

Acute lung epithelial injury caused by P. aeruginosa

Acute lung injury in animal models

P. aeruginosa secretes various toxic exoproducts (Table 1). Investigation of the toxic exoproducts of P. aeruginosa with major roles in acute lung injury began in the late 1980s. In animal models, acute lung epithelial injury was quantified through the measurement of bidirectional protein movement across the lung epithelial barrier [12–14]. In this model, the airspace instillation of live P. aeruginosa resulted in increased movement of the alveolar tracer into the vascular compartment, a twofold increase in the vascular tracer in the airspace, and a significant reduction in liquid clearance by the lung, while instillation of Escherichia coli endotoxin did not cause lung epithelial injury. These early animal experiments initiated the search for a major virulence factor responsible for acute lung epithelial injury among the exoproducts of P. aeruginosa[15, 16].

Discovery of a major cytotoxin: ExoU

The P. aeruginosa toxin exoenzyme S was identified in the late 1970s as an ADP-ribosyltransferase distinct from exotoxin A [17, 18]. Early studies revealed that the exoenzyme S-positive phenotype correlated with increased virulence in lung infections and burn wounds [19–24]. The protein transcriptional regulator ExsA was found to regulate the production of exoenzyme S and co-regulated proteins [25–27]. PAO-S21, an insertional mutant of transposon Tn501 in the exsA gene of P. aeruginosa, is exoenzyme S-deficient [15, 19]. PAO-S21 infection did not result in altered protein flux across the alveolar epithelial barrier [15]. Based on these findings, exoenzyme S, or an unknown exoenzyme S-related toxin regulated by ExsA, was determined to play a major role in acute lung injury. Exoenzyme S activity was later determined to be the result of two highly homologous toxins, ExoS (a 49-kDa form of exoenzyme S) and ExoT (a 53-kDa form of exoenzyme S), encoded by two separate regions of the P. aeruginosa genome [28–31].

The virulent P. aeruginosa strain PA103, lacking the 49-kDa form of the exoenzyme S gene (exoS) but possessing the 53-kDa form (exoT), causes a high degree of acute injury [16]. Because the isogenic mutant lacking the 49-kDa form of exoenzyme S remained capable of causing acute lung injury in a rabbit model, it was initially considered possible that ExoT is the major factor underlying acute lung injury [16]. However, an isogenic mutant lacking ExoT remained capable of causing alveolar epithelial injury in a mouse model [32]. Thus, neither ExoT nor ExoS was the major virulence factor. PA103 was found to secrete a unique unknown 74-kDa protein, the production of which decreased with a transposon mutation in exsA. The gene encoding this 74-kDa protein was cloned, and a mutant missing this protein was created in PA103. PA103 lacking this 74-kDa protein failed to cause acute lung injury in our mouse model [33, 34]. This protein, regulated by ExsA, was named ExoU. Clinical isolates with a cytotoxic phenotype in vitro were found to express ExoU and cause acute epithelial injury in a mouse model [33]. Cytotoxic P. aeruginosa isolates were identified to possess exoU, while noncytotoxic isolates lacked the gene [33]. High cytotoxicity, severity of lung epithelial injury, and bacterial dissemination into the circulation appeared to show a high correlation with the exoU genotype [35, 36]. Therefore, it was concluded that the ability of P. aeruginosa to cause acute lung epithelial injury and sepsis is highly linked to the expression of ExoU, regulated by the transcriptional activator ExsA [33, 34].

Type III secretion system

The secretion systems of gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria, which have inner and outer bacterial membranes, use dedicated secretion systems to transport proteins synthesized to the outside environment. The secretion systems of gram-negative bacteria can be classified into six subtypes [37]. The type I secretion system is relatively simple, consisting of only a few proteins. Unlike proteins secreted by the type II secretion system, proteins secreted by the type I secretion system contain no signal sequence at their amino termini; instead, they contain domains at their carboxyl termini necessary for recognition by the type I secretion complex. The type II system conducts so-called sec-dependent secretion [38]. Proteins secreted by the type II system possess amino-terminal signal sequences of 16–26 residues [38].

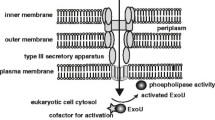

The type III and IV secretion systems have been more recently defined (Figure 1). Recently, a high degree of association has been reported to exist between the type III and IV secretion systems and the pathogenesis of gram-negative bacteria [37, 39]. In both the secretion systems, bacteria directly deliver proteins into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells [40]. Evolutionarily, TTSS is derived from flagella, while the type IV system is derived from a conjugational system [39, 41]. TTSS is utilized by most pathogenic gram-negative bacteria, including Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa (Table 2) [42]. TTSS functions as a molecular syringe, directly delivering toxins into the cytosol of cells [43]. The translocated toxins modulate eukaryotic cell signaling. All TTSSs studied till date share an important feature: the genes encoding this system are upregulated by direct contact between bacteria and host cells, with consequent direct delivery of bacterial virulence products (type III secretory toxins or effector molecules) into the host cell via the secretion and translocation apparatus [42]. In P. aeruginosa, exoenzyme S was initially thought to be secreted via the type II secretion pathway. However, based on the genomic homology to other gram-negative bacteria, this toxin and co-regulated toxins (ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY) were ultimately determined to be translocated as effector proteins into host cells via TTSS [44].

Gram-negative bacterial protein secretion system. In the type I and II secretion systems, bacteria secrete toxins into the extracellular space (upper image). In the type III and IV secretion systems, bacteria directly secrete toxins into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells through the secretion apparatus (lower image).

Genomic organization of P. aeruginosa TTSS

TTSS of P. aeruginosa is highly homologous to the prototypical Yersinia TTSS [45, 46]. The whole genome of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was sequenced by the Pseudomonas Genome Project and published in 2000 (Figure 2) [47]. It was found that the 25.6-kb genomic region, named the exoenzyme S regulon, encodes genes underlying the regulation, secretion, and translocation of TTSS [48]. Expression of these genes is under the regulation of the transcriptional activator protein ExsA, and ExsA itself is encoded by the exsCBA operon in the exoenzyme S regulon [28, 48].

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome and type III secretion regulon and toxin genes. The genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was completely sequenced by the Pseudomonas Genome Project in 2000. Within the 6.3-Mb region, 5,570 open reading frames were found. The type III secretion regulatory region (25.5 kb) was found as a gene cluster and named the exoenzyme S regulon. It comprised five operons, including 36 genes for transcription (exsA-exsD), secretion apparatus (pscB-pscU), and translocation (pcrGVHpopBD). The genes of the type III secretory toxins exoS, exoT, and exoY, but not exoU, were scattered throughout the genome. The exoU gene was found to be located in an insertional pathogenic gene cluster named P. aeruginosa pathogenicity island-2 (PAPI-2) discovered in the virulent clinical strain PA14.

In the genome of P. aeruginosa PAO1, three type III secretory toxins (excluding ExoU), co-regulated with the exoenzyme S regulon by ExsA, have been identified (Figure 2). These are ExoS (a 49-kDa form of exoenzyme S), ExoT (a 53-kDa form of exoenzyme S, also known as exoenzyme T), and ExoY [31, 49]. The genes encoding these type III secretory toxins (exoS, exoT, and exoY) are distributed in regions of the genome separate from the exoenzyme S regulon [47, 48]. Later, two distinct P. aeruginosa pathogenicity islands, PAPI-1 (108 kb) and PAPI-2 (11 kb), which are absent from the less virulent strain PAO1, were found in the highly virulent clinical strain PA14, and exoU was discovered in the PAPI-2 region of this strain [50, 51]. Approximately 20% of clinical isolates are more virulent; they possess exoU, but not exoS[52].

The exoenzyme S regulon

Transcriptional activator ExsA

ExsA, encoded by the exsCBA operon (the trans-regulatory locus for exoenzyme S secretion) in the exoenzyme S regulon, is a transcriptional activator of the P. aeruginosa TTSS [48]. In the exoenzyme S regulon, ExsA regulates the transcription of five operons (exsD-pscL, exsCBA, pscG-popD, popN-pcrR, and pscN-pscU) encoding TTSS and the translocation machinery (Figure 2) [48]. Another four or five ExsA-binding sites have been found in the genome for the regulation of effector molecules (type III secretory toxins) and their chaperones [47].

Secretion apparatus

In TTSS, secretion describes the process by which toxins are transferred from the bacterial cytosol to the surrounding medium across the inner and outer bacterial membranes [43]. This process seems to require secretion apparatus involving many protein components (Figure 3). All known TTSSs in animals and pathogenic bacteria share a number of highly conserved core structural components. The TTSS-specific export apparatus is termed the needle complex in Salmonella[53, 54], Shigella[55], and E. coli[56]. This structure spans both the inner and outer membranes of the bacterial envelope and closely resembles the flagella basal body, further supporting the evolutionary relationship between the flagella and TTSS [41, 57].

In Yersinia, ysc genes in the Yop virulon largely encode components of TTSS, and P. aeruginosa possesses homologous psc genes in its exoenzyme regulon [45, 48]. Ysc proteins from Yersinia ysc genes and Psc proteins from P. aeruginosa psc genes are considered as components of their respective needle complexes because of their sequence homology to Salmonella Spa, Prg, and Inv; Shigella Spa and Mxi; and E. coli Esc proteins.

Translocators and V-antigen

In TTSS, translocation, which describes the process of direct toxin transfer into the eukaryotic cytosol across the eukaryotic plasma membrane, has been thoroughly investigated in Yersinia[45, 58–60]. In P. aeruginosa, the pcrGVHpopBD operon, under regulation by ExsA, encodes five proteins, namely PcrG, PcrV, PcrH, PopB, and PopD, homologous to Yersinia LcrG, LcrV, LcrH, YopB, and YopD, respectively (Table 3) [61, 62]. Translocation in the P. aeruginosa TTSS is mediated by PcrV, PopB, and PopD. In fact, in P. aeruginosa, isogenic mutants lacking pcrV or popD were unable to intoxicate eukaryotic cells [63, 64]. Historically, Yersinia LcrV was designated Yersinia V-antigen and thought to protect mice from lethal infections with yersiniae strains [65, 66]. PcrV (P. aeruginosa V-antigen) corresponds to the Yersinia V-antigen LcrV. Antibodies against LcrV and PcrV are likely to block type III protein translocation by interfering with pore formation by LcrV/YopB/YopD and PcrV/PopB/PopD, respectively [63, 64].

Four type III secretory toxins of P. aeruginosa

Till date, P. aeruginosa is known to secrete at least four effector molecules (type III secretory toxins) via TTSS: ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY (Table 4, Figure 4). The virulence of each strain differs depending on the genotypes and phenotypes of the type III secretory toxins [32, 33, 52].

Contact-dependent toxin translocation during type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . P. aeruginosa translocates toxins after direct contact with the surface of the target eukaryotic cell. ExoS and ExoT modulate the cytoskeleton and endocytosis through interaction with Ras and/or Rho GTPases; ExoU disrupts the integrity of the lipid membrane by targeting phospholipids; and ExoY causes edema formation by increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

ExoS

P. aeruginosa exoenzyme S was originally characterized as a toxin distinct from exotoxin A exhibiting ADP-ribosyltransferase activity [17]. Exoenzyme S ADP-ribosylates vimentins and several Ras-related GTP-binding proteins, including Rab3, Rab4, Ral, Rap1A, and Rap2 [67, 68]. The enzymatic reaction requires a soluble eukaryotic protein, termed factor-activating exoenzyme S (FAS), to ADP-ribosylate all substrates [69, 70]. Analysis of several deletion peptides showed that 222 amino acids at the carboxyl terminal of exoenzyme S possessed FAS-dependent ADP-ribosyltransferase activity [69, 70]. Expression of the ADP-ribosyltransferase domain of exoenzyme S is cytotoxic to eukaryotic cells [71].

The amino-terminal domain of exoenzyme S has been characterized as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for Rho GTPases [72], suggesting that exoenzyme S is a bifunctional type III secreted cytotoxin [71]. In vivo data indicate that the Rho GAP activity of ExoS stimulates the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton by inhibiting Rac and Cdc42 and stimulates actin stress fiber formation by inhibiting Rho [73].

ExoT

Two immunologically undistinguishable proteins, with apparent molecular sizes of 53- and 49-kDa, co-fractionated with exoenzyme S activity [18]. Later, these two exoenzymes were found to be the products of two different genes [31]. ExoT was found to encode a protein of 457 amino acids, with 75% amino acid homology to ExoS. However, ExoT possessed approximately 0.2% of its ADP-ribosyltransferase activity [74]. ExoT diminishes macrophage motility and phagocytosis, at least in part through disruption of the actin cytoskeleton of eukaryotic cells, and blocks wound healing [75, 76]. Biochemical studies have shown that ExoT is a GAP for RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 [77, 78]. These data show that ExoT interferes with the Rho signal transduction pathways, which regulate actin organization, exocytosis, cell cycle progression, and phagocytosis [77, 79].

ExoU

In 1997, a novel cytotoxin, ExoU (termed PepA by Hauser et al. [34]), was found to be a major contributory factor to lung injury, and the gene exoU was cloned from the cytotoxic PA103 strain. A region downstream of exoU was found to encode a specific Pseudomonas chaperone for ExoU (SpcU) [80]. In P. aeruginosa, ExoU and SpcU are coordinately expressed as an operon controlled at the transcriptional level by ExsA [80]. Acquisition of the expression of P. aeruginosa ExoU caused increased bacterial virulence and systemic spread in a mouse model of acute pneumonia [33]. Hauser et al. determined the type III secretion genotypes and phenotypes of isolates cultured from patients with VAP: in vitro assays indicated that ExoU most closely linked to mortality in animal models was secreted in detectable amounts in vitro by 10 (29%) of the 35 isolates examined [34].

ExoU has a potato patatin-like phospholipase (PLA) domain (pfam01734 in the Conserved Domain Database of BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA); Figure 5). Patatin is a member of a multigene family of vacuolar storage glycoproteins with lipid acyl hydrolase and acyltransferase activities; it represents 40% of the total soluble protein in potato tubers [81]. Sequence alignment of ExoU, potato patatin, and human PLA2 revealed three highly conserved regions in the amino acid sequence of ExoU [82]. In the alignment, Ser-142 and Asp-344 of ExoU corresponded to the catalytic serine and aspartate of PLA2, respectively [82]. Subsequently, using in vitro models, it was shown that ExoU exhibits Ser-142- and Asp-344-dependent catalytic PLA2 activity, which requires eukaryotic cell factors for its activation [82, 83]. Then, it was finally concluded that virulent P. aeruginosa causes acute lung injury, thereby causing sepsis and mortality, through cytotoxic activity derived from the patatin-like phospholipase domain of ExoU [84]. The cells targeted by ExoU injection through TTSS comprise not only epithelial cells but also macrophages [85]. Through TTSS, ExoU is activated after its translocation into the eukaryotic cell cytosol. It has been recently reported that ubiquitin and ubiquitin-modified proteins are associated with ExoU activation [86, 87].

The molecular structure and functional targets of ExoU. P. aeruginosa ExoU, a major factor causing cytotoxicity and epithelial injury in the lung, contains a patatin domain that catalyzes membrane phospholipids through phospholipase A2 activity. Homology in the amino acid sequence, with a catalytic dyad in the primary structure, was found between patatin, mammalian phospholipase A2 (cPLA2-α and iPLA2), and ExoU. FFA free fatty acid.

ExoY

ExoY is the fourth type III secretion effector protein controlled by ExoS regulon. ExoY is homologous to the extracellular adenylate cyclases of Bortedella pertussis (CyaA), Bacillus anthracis (EF), and Yersinia pestis (insecticidal toxin) [49]. In assays for adenylate cyclase activity, recombinant ExoY (rExoY) catalyzed the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). In contrast to CyaA and EF, rExoY activity was not stimulated or activated by calmodulin. Infection of eukaryotic cells with P. aeruginosa producing catalytically active ExoY resulted in the elevation of intracellular cAMP levels and changes in cell morphology [88, 89]. It is more recently reported that ExoY is likely to be a promiscuous nucleotidal cyclase that increases the intracellular levels of cyclic adenosine and guanosine monophosphates, resulting in edema formation [90].

Epidemiology of the P. aeruginosa TTSS

Analysis of type III secretory protein phenotypes was performed in 108 isolates derived from patients with P. aeruginosa infections [52]. The mortality rate in patients with P. aeruginosa isolates expressing at least one of the type III secretory proteins was 21% compared with the rate of 3% in patients with isolates expressing no type III secretory protein. In another study, infection with isolates secreting TTSS proteins, particularly isolates with an ExoU-positive phenotype, correlated with severe disease [91]. Recently, additional reports have demonstrated an association between the ExoU genotype or phenotype and a poor clinical outcome of P. aeruginosa pneumonia. exoU-positive isolates were more likely to be fluoroquinolone resistant and exhibit both a gyrA mutation and efflux pump overexpression [92]. Clinical isolates containing the exoU gene were more likely to be resistant to cefepime, ceftazidime, piperacillin tazobactam, carbapenems, and gentamicin [93]. A fluoroquinolone-resistant phenotype in an ExoU-positive strain contributes to the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa in pneumonia [94]. However, the expression of TTSS exoenzymes in P. aeruginosa isolates from bacteremic patients confers a poor clinical outcome, independent of antibiotic susceptibility [95]. Severity of the illness and expression of type III secretory proteins were the strongest predictors of 30-day mortality from P. aeruginosa bacteremia [96].

Update the clinical approach against P. aeruginosa pneumonia

P. aeruginosa expresses a variety of factors that confer resistance to a broad array of antibacterial agents. Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa (MDRP) is defined as the resistance to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones. The current increase in the incidence of lethal outbreaks of MDRP is especially a serious concern. Multiple genetic rearrangements, such as chromosomal mutations or horizontal gene transfers (plasmids, integrons, phages), are associated with the acquisition of multidrug resistance in these bacteria. The various mechanisms, such as β-lactamases, carbapenemases or aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, and mutations in antibiotic targets, efflux pumps, impermeability, are associated in these multidrug resistances. In the management of P. aeruginosa pneumonia, the increasing resistance level of these bacteria to most classes of antibacterial agents frequently leads to failure of effective treatment, which is associated with high mortality of the infected patients. Therefore, choosing adequate antibiotics is crucial to increase the survival rate, especially in patients infected with MDRP. Therefore, surveillance in antibiotic resistance must be important to reduce the risk of inadequate antibacterial therapy. In addition, surveillance in TTSSgenotype- and phenotype-associated acute lung injury and sepsis may help to predict the higher risk of lethal outbreaks.

Polymyxin E (colistin) remains the most consistently effective agent against MDPR, while colistin-resistant P. aeruginosa has been already reported as a caution of the emergence of pan-resistant strains in the near future [97]. Different strategies against the different targets must be required before the spread of super-resistant strains. Among various experimental therapeutic approaches, the anti-TTSS therapy is reasonable because acute lung injury due to P. aeruginosa is highly depending on its TTSS-associated virulence as described above. PcrV has a critical role in the TTS-associated virulence of P. aeruginosa as follows [63]. In a series of these studies, active and passive immunization against PcrV in animal models of P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury greatly increased survival [63]. Virulent P. aeruginosa strains expressing PcrV disabled macrophage phagocytosis. However, antibodies against PcrV blocked this critical antiphagocytic effect [63]. Passive protection with anti-PcrV reduced the inflammatory response, minimized bacteremia, and prevented septic shock in mice and rabbits [98]. The protective capacity of the antibody was Fc-independent as F(ab′)2 fragments of polyclonal anti-PcrV were also effective [98]. A murine monoclonal anti-PcrV antibody mAb166 was developed, and its protective effects on acute lung injury were demonstrated when co-instilled with the bacterial challenge or passively transferred to infected animals [99]. The administration of either mAb166 or Fab of mAb166 showed comparable therapeutic effects to rabbit polyclonal anti-PcrV IgG [100]. Based on mAb166, humanized anti-PcrV antibody that was developed by molecular engineering has recently entered phase I/II clinical trials in the USA and Europe for prophylactic and therapeutic uses against P. aeruginosa pneumonia in artificially ventilated patients and cystic fibrosis patients [101–103].

Conclusions

Summary and future implications

P. aeruginosa possesses a sophisticated toxin secretion system to directly inject toxins into the cytosol of target eukaryotic cells. This system, called TTSS, is regulated by the exoenzyme S regulon of P. aeruginosa. Through TTSS, P. aeruginosa translocates the type III secretory toxins ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY. By injecting these toxins into the cytosol of eukaryotic cells, P. aeruginosa exploits mammalian enzyme functions to modulate eukaryotic cell signaling.

Of these four toxins, ExoU is the major virulence factor responsible for alveolar epithelial injury in P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Virulent strains of P. aeruginosa possess the exoU gene, whereas nonvirulent strains lack the same. The major pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa-induced acute epithelial lung injury and subsequent bacteremia and sepsis is highly dependent on the ExoU phenotype of the strain, while the type III secretory toxins ExoS, ExoT, and ExoY modulate host immunity and cause lung edema (Figure 6). Progress in the field of translational research is now anticipated to prevent the acute lung injury and improve the poor clinical outcome of P. aeruginosa pneumonia. What we have learned from our attempts to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying acute lung injury over the last 30 years is how well pathogenic bacteria utilize our cell signaling to cause diseases: bacteria know our cell signaling better than we do.

Acute lung injury caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . P. aeruginosa secretes and injects type III secretory toxins (ExoS, ExoT, ExoU, and ExoY) into alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells, blocking macrophage phagocytosis, inducing epithelial disruption, and causing the dissemination of bacterial and inflammatory mediators from the airspace into the systemic circulation, which eventually results in bacteremia and sepsis. AMΦ alveolar macrophages, IL-1 interleukin-1, IL-8 interleukin-8, TNF tumor necrosis factor.

Authors’ information

TS is a professor in Anesthesiology at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Japan.

Abbreviations

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- cGMP:

-

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- ExsA:

-

Transcriptional regulator ExsA

- FAS:

-

Factor-activating exoenzyme S

- GAP:

-

GTPase-activating protein

- PAPI:

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity island

- TTSS:

-

Type III secretion system

- PLA:

-

Patatin-like phospholipase

- PLA2:

-

Phospholipase A2

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia.

References

Quartin AA, Scerpella EG, Puttagunta S, Kett DH: A comparison of microbiology and demographics among patients with healthcare-associated, hospital-acquired, and ventilator-associated pneumonia: a retrospective analysis of 1,184 patients from a large, international study. Int J Infect Dis 2011, 15: e545-e550. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.04.005

Restrepo MI, Anzueto A: The role of gram-negative bacteria in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 30: 61-66. 10.1055/s-0028-1119810

Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF: Epidemiology of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP). Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 30: 10-15. 10.1055/s-0028-1119804

Di Pasquale M, Ferrer M, Esperatti M, Crisafulli E, Giunta V, Bassi GL, Rinaudo M, Blasi F, Niederman M, Torres A: Assessment of severity of ICU-acquired pneumonia and association with etiology. Crit Care Med 2014,42(2):303-312. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a272a2

Arabi Y, Al-Shirawi N, Memish Z, Anzueto A: Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults in developing countries: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis 2008, 12: 505-512. 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.02.010

Suk Lee M, Walker V, Chen LF, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ: The epidemiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a network of community hospitals: a prospective multicenter study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013, 34: 657-662. 10.1086/670991

Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J, Dellamonica P, Gouin F, Lepoutre A, Mercier JC, Offenstadt G, Regnier B: Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. JAMA 1995, 274: 968-974. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530120060042

Vidal F, Mensa J, Almela M, Martinez JA, Marco F, Casals C, Gatell JM, Soriano E, de Anta MTJ: Epidemiology and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia, with special emphasis on the influence of antibiotic treatment. Analysis of 189 episodes. Arch Intern Med 1996, 156: 2121-2126. 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440170139015

Tumbarello M, De Pascale G, Trecarichi EM, Spanu T, Antonicelli F, Maviglia R, Pennisi MA, Bello G, Antonelli M: Clinical outcomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 2013, 39: 682-692. 10.1007/s00134-013-2828-9

Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T, Kurahashi K, Ohara M, Gropper MA: Pulmonary edema associated with bacterial pneumonia. In Pulmonary Edema. Edited by: Matthay M, Matthay M, Ingbar D. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1998:247-267.

Wiener-Kronish JP, Frank DW, Sawa T: Mechanisms of acute lung epithelial cell injury by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . In Molecular and Cellular Biology of Critical Care Medicine Volume 1 Molecular Biology of Acute Lung Injury. Edited by: Wong HR, Shanley TP. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001:149-161.

Wiener-Kronish JP, Broaddus VC, Albertine KH, Gropper MA, Matthay MA, Staub NC: Relationship of pleural effusions to increased permeability pulmonary edema in anesthetized sheep. J Clin Invest 1988, 2: 1422-1429.

Wiener-Kronish JP, Albertine KH, Matthay MA: Differential responses of the endothelial and epithelial barriers of the lung in sheep to Escherichia coli endotoxin. J Clin Invest 1991, 88: 864-875. 10.1172/JCI115388

Pittet JF, Matthay MA, Pier G, Grady M, Wiener-Kronish JP: Pseudomonas aeruginosa -induced lung and pleural injury in sheep. Differential protective effect of circulating versus alveolar immunoglobulin G antibody. J Clin Invest 1993, 92: 1221-1228. 10.1172/JCI116693

Wiener-Kronish JP, Sakuma T, Kudoh I, Pittet JF, Frank D, Dobbs L, Vasil ML, Matthay MA: Alveolar epithelial injury and pleural empyema in acute P. aeruginosa pneumonia in anesthetized rabbits. J Appl Physiol 1993, 75: 1661-1669.

Kudoh I, Wiener-Kronish JP, Hashimoto S, Pittet JF, Frank D: Exoproduct secretions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains influence severity of alveolar epithelial injury. Am J Physiol 1994, 267: L551-L556.

Iglewski BH, Sadoff J, Bjorn MJ, Maxwell ES: Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S: an adenosine diphosphate ribosyltransferase distinct from toxin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1978, 75: 3211-3215. 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3211

Sokol PA, Iglewski BH, Hager TA, Sadoff JC, Cross AS, McManus A, Farber BF, Iglewski WJ: Production of exoenzyme S by clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Infect Immun 1981, 34: 147-153.

Nicas TI, Iglewski BH: Isolation and characterization of transposon-induced mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa deficient in production of exoenzyme S. Infect Immun 1984, 45: 470-474.

Nicas TI, Iglewski BH: The contribution of exoproducts to virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Can J Microbiol 1985, 31: 387-392. 10.1139/m85-074

Nicas TI, Iglewski BH: Contribution of exoenzyme S to the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Antibiot Chemother (1971) 1985, 36: 40-48.

Nicas TI, Frank DW, Stenzel P, Lile JD, Iglewski BH: Role of exoenzyme S in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol 1985, 4: 175-179. 10.1007/BF02013593

Nicas TI, Bradley J, Lochner JE, Iglewski BH: The role of exoenzyme S in infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Infect Dis 1985, 152: 716-721. 10.1093/infdis/152.4.716

Bjorn MJ, Pavlovskis OR, Thompson MR, Iglewski BH: Production of exoenzyme S during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections of burned mice. Infect Immun 1997, 24: 837-842.

Frank DW, Iglewski BH: Cloning and sequence analysis of a trans-regulatory locus required for exoenzyme S synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol 1991, 173: 6460-6468.

Frank DW, Nair G, Schweizer HP: Construction and characterization of chromosomal insertional mutations of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S trans-regulatory locus. Infect Immun 1994, 62: 554-563.

Hovey AK, Frank DW: Analyses of the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation properties of ExsA, the transcriptional activator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J Bacteriol 1995, 177: 4427-4436.

Goranson J, Frank DW: Genetic analysis of exoenzyme S expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . FEMS Microbiol Lett 1996, 135: 149-155. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07981.x

Kulich SM, Frank DW, Barbieri JT: Purification and characterization of exoenzyme S from Pseudomonas aeruginosa 388. Infect Immun 1993, 61: 307-313.

Kulich SM, Yahr TL, Mende-Mueller LM, Barbieri JT, Frank DW: Cloning the structural gene for the 49-kDa form of exoenzyme S (exoS) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain 388. J Biol Chem 1994, 269: 10431-10437.

Yahr TL, Barbieri JT, Frank DW: Genetic relationship between the 53- and 49-kilodalton forms of exoenzyme S from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol 1996, 178: 1412-1419.

Fleiszig SM, Wiener-Kronish JP, Miyazaki H, Vallas V, Mostov KE, Kanada D, Sawa T, Yen TS, Frank DW: Pseudomonas aeruginosa -mediated cytotoxicity and invasion correlate with distinct genotypes at the loci encoding exoenzyme S. Infect Immun 1997, 65: 579-586.

Finck-Barbancon V, Goranson J, Zhu L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Fleiszig SM, Wu C, Mende-Mueller L, Frank DW: ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Mol Microbiol 1997, 25: 547-557. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4891851.x

Hauser AR, Kang PJ, Engel JN: PepA, a secreted protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa , is necessary for cytotoxicity and virulence. Mol Microbiol 1998, 27: 807-818. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00727.x

Kurahashi K, Kajikawa O, Sawa T, Ohara M, Gropper MA, Frank DW, Martin TR, Wiener-Kronish JP: Pathogenesis of septic shock in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Clin Invest 1999, 104: 743-750. 10.1172/JCI7124

Allewelt M, Coleman FT, Grout M, Priebe GP, Pier GB: Acquisition of expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU cytotoxin leads to increased bacterial virulence in a murine model of acute pneumonia and systemic spread. Infect Immun 2000, 68: 3998-4004. 10.1128/IAI.68.7.3998-4004.2000

Schesser K, Schesser K, Francis MS, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H: Type III secretion systems in animal- and plant interacting bacteria. In Cellular Microbiology. 1st edition. Edited by: Cossart P, Boquet P, Normark SR, Rappuoli R. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2000:239-264.

Sandkvist M: Biology of type II secretion. Mol Microbiol 2001, 40: 271-283. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02403.x

Christie PJ: Type IV secretion: intercellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol Microbiol 2001, 40: 294-305. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02302.x

Cheng LW, Schneewind O: Type III machines of Gram-negative bacteria: delivering the goods. Trends Microbiol 2000, 8: 214-220. 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01665-0

Aizawa SI: Bacterial flagella and type III secretion systems. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2001, 202: 157-164. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10797.x

Hueck CJ: Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1998, 62: 379-433.

Lee CA: Type III secretion systems: machines to deliver bacterial proteins into eukaryotic cells? Trends Microbiol 1997, 5: 148-156. 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01029-9

Yahr TL, Goranson J, Frank DW: Exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa i s secreted by a type III pathway. Mol Microbiol 1996, 22: 991-1003. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01554.x

Cornelis GR, Wolf-Watz H: The Yersinia Yop virulon: a bacterial system for subverting eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol 1997, 23: 861-867. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2731623.x

Yahr TL, Mende-Mueller LM, Friese MB, Frank DW: Identification of type III secreted products of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J Bacteriol 1997, 179: 7165-7168.

Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou , Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, et al.: Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 2000, 406: 959-964. 10.1038/35023079

Frank DW: The exoenzyme S regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Mol Microbiol 1997, 26: 621-629. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6251991.x

Yahr TL, Vallis AJ, Hancock MK, Barbieri JT, Frank DW: ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95: 13899-13904. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13899

Wolfgang MC, Kulasekara BR, Liang X, Boyd D, Wu K, Yang Q, Miyada CG, Lory S: Conservation of genome content and virulence determinants among clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100: 8484-8489. 10.1073/pnas.0832438100

He J, Baldini RL, Déziel E, Saucier M, Zhang Q, Liberati NT, Lee D, Urbach J, Goodman HM, Rahme LG: The broad host range pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 carries two pathogenicity islands harboring plant and animal virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101: 2530-2535. 10.1073/pnas.0304622101

Roy-Burman A, Savel RH, Racine S, Swanson BL, Revadigar NS, Fujimoto J, Sawa T, Frank DW, Wiener-Kronish JP: Type III protein secretion is associated with death in lower respiratory and systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Infect Dis 2001, 183: 1767-1774. 10.1086/320737

Kubori T, Matsushima Y, Nakamura D, Uralil J, Lara-Tejero M, Sukhan A, Galan JE, Aizawa SI: Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science 1998, 280: 602-605. 10.1126/science.280.5363.602

Galan JE, Collmer A: Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science 1999, 284: 1322-1328. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322

Tamano K, Aizawa S, Katayama E, Nonaka T, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Kuwae A, Nagai S, Sasakawa C: Supramolecular structure of the Shigella type III secretion machinery: the needle part is changeable in length and essential for delivery of effectors. EMBO J 2000, 19: 3876-3887. 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3876

Sekiya K, Ohishi M, Ogino T, Tamano K, Sasakawa C, Abe A: Supermolecular structure of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secretion system and its direct interaction with the EspA-sheath-like structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001, 98: 11638-11643. 10.1073/pnas.191378598

Schraidt O, Marlovits TC: Three-dimensional model of Salmonella ’s needle complex at subnanometer resolution. Science 2011, 331: 1192-1195. 10.1126/science.1199358

Hakansson S, Bergman T, Vanooteghem JC, Cornelis G, Wolf-Watz H: YopB and YopD constitute a novel class of Yersinia Yop proteins. Infect Immun 1993, 61: 71-80.

Hakansson S, Schesser K, Persson C, Galyov EE, Rosqvist R, Homble F, Wolf-Watz H: The YopB protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is essential for the translocation of Yop effector proteins across the target cell plasma membrane and displays a contact-dependent membrane disrupting activity. EMBO J 1996, 15: 5812-5823.

Nordfelth R, Wolf-Watz H: YopB of Yersinia enterocolitica is essential for YopE translocation. Infect Immun 2001, 69: 3516-3518. 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3516-3518.2001

Schoehn G, Di Guilmi AM, Lemaire D, Attree I, Weissenhorn W, Dessen A: Oligomerization of type III secretion proteins PopB and PopD precedes pore formation in Pseudomonas . EMBO J 2003, 22: 4957-4967. 10.1093/emboj/cdg499

Allmond LR, Karaca TJ, Nguyen VN, Nguyen T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T: Protein binding between PcrG-PcrV and PcrH-PopB/PopD encoded by the pcrGVH-popBD operon of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. Infect Immun 2003, 71: 2230-2233. 10.1128/IAI.71.4.2230-2233.2003

Sawa T, Yahr TL, Ohara M, Kurahashi K, Gropper MA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Frank DW: Active and passive immunization with the Pseudomonas V antigen protects against type III intoxication and lung injury. Nat Med 1999, 5: 392-398. 10.1038/7391

Pettersson J, Holmstrom A, Hill J, Leary S, Frithz-Lindsten E, von Euler-Matell A, Carlsson E, Titball R, Forsberg Å, Wolf-Watz H: The V-antigen of Yersinia is surface exposed before target cell contact and involved in virulence protein translocation. Mol Microbiol 1999, 32: 961-976. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01408.x

Burrows TW: An antigen determining virulence in Pasteurella pestis . Nature 1956, 177: 426-427.

Une T, Brubaker RR: Roles of V antigen in promoting virulence and immunity in yersiniae . J Immunol 1984, 133: 2226-2230.

Coburn J, Dillon ST, Iglewski BH, Gill DM: Exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ADP-ribosylates the intermediate filament protein vimentin. Infect Immun 1989, 57: 996-998.

Coburn J, Wyatt RT, Iglewski BH, Gill DM: Several GTP-binding proteins, including p21c-H-ras, are preferred substrates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S. J Biol Chem 1989, 264: 9004-9008.

Coburn J, Kane AV, Feig L, Gill DM: Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S requires a eukaryotic protein for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 1991, 266: 6438-6446.

Fu H, Coburn J, Collier RJ: The eukaryotic host factor that activates exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a member of the 14-3-3 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90: 2320-2324. 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2320

Barbieri JT: Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S, a bifunctional type-III secreted cytotoxin. Int J Med Microbiol 2000, 290: 381-387. 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80047-8

Goehring UM, Schmidt G, Pederson KJ, Aktories K, Barbieri JT: The N-terminal domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S is a GTPase-activating protein for Rho GTPases. J Biol Chem 1999, 274: 36369-36372. 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36369

Krall R, Sun J, Pederson KJ, Barbieri JT: In vivo rho GTPase-activating protein activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoS. Infect Immun 2002, 70: 360-367. 10.1128/IAI.70.1.360-367.2002

Liu S, Yahr TL, Frank DW, Barbieri JT: Biochemical relationships between the 53-kilodalton (Exo53) and 49-kilodalton (ExoS) forms of exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol 1997, 179: 1609-1613.

Cowell BA, Chen DY, Frank DW, Vallis AJ, Fleiszig SM: ExoT of cytotoxic Pseudomonas aeruginosa prevents uptake by corneal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 2000, 68: 403-406. 10.1128/IAI.68.1.403-406.2000

Geiser TK, Kazmierczak BI, Garrity-Ryan LK, Matthay MA, Engel JN: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT inhibits in vitro lung epithelial wound repair. Cell Microbiol 2001, 3: 223-236. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00107.x

Krall R, Schmidt G, Aktories K, Barbieri JT: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT is a Rho GTPase-activating protein. Infect Immun 2000, 68: 6066-6068. 10.1128/IAI.68.10.6066-6068.2000

Kazmierczak BI, Engel JN: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT acts in vivo as a GTPase-activating protein for RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42. Infect Immun 2002, 70: 2198-2205. 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2198-2205.2002

Garrity-Ryan L, Kazmierczak B, Kowal R, Comolli J, Hauser A, Engel JN: The arginine finger domain of ExoT contributes to actin cytoskeleton disruption and inhibition of internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by epithelial cells and macrophages. Infect Immun 2000, 68: 7100-7113. 10.1128/IAI.68.12.7100-7113.2000

Finck-Barbancon V, Yahr TL, Frank DW: Identification and characterization of SpcU, a chaperone required for efficient secretion of the ExoU cytotoxin. J Bacteriol 1998, 180: 6224-6231.

Racusen D: Lipid acyl hydrolase of patatin. Can J Bot 1984, 62: 1640-1644. 10.1139/b84-220

Sato H, Frank DW, Hillard CJ, Feix JB, Pankhaniya RR, Moriyama K, Finck-Barbancon V, Buchaklian A, Lei M, Long RM, Wiener-Kronish J, Sawa T: The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa -encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. EMBO J 2003, 22: 2959-2969. 10.1093/emboj/cdg290

Tamura M, Ajayi T, Allmond LR, Moriyama K, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T: Lysophospholipase A activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretory toxin ExoU. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 316: 323-331. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.050

Pankhaniya RR, Tamura M, Allmond LR, Moriyama K, Ajayi T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T: Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes acute lung injury via the catalytic activity of the patatin-like phospholipase domain of ExoU. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 2293-2299.

Diaz MH, Hauser AR: Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU is injected into phagocytic cells during acute pneumonia. Infect Immun 2010, 78: 1447-1456. 10.1128/IAI.01134-09

Anderson DM, Schmalzer KM, Sato H, Casey M, Terhune SS, Haas AL, Feix JB, Frank DW: Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-modified proteins activate the Pseudomonas aeruginosa T3SS cytotoxin, ExoU. Mol Microbiol 2011, 82: 1454-1467. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07904.x

Anderson DM, Feix JB, Monroe AL, Peterson FC, Volkman BF, Haas AL, Frank DW: Identification of the major ubiquitin-binding domain of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU A2 phospholipase. J Biol Chem 2013, 288: 26741-26752. 10.1074/jbc.M113.478529

Sayner SL, Frank DW, King J, Chen H, VandeWaa J, Stevens T: Paradoxical cAMP-induced lung endothelial hyperpermeability revealed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoY. Circ Res 2004, 95: 196-203. 10.1161/01.RES.0000134922.25721.d9

Cowell BA, Evans DJ, Fleiszig SM: Actin cytoskeleton disruption by ExoY and its effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasion. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2005, 250: 71-76. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.044

Ochoa CD, Alexeyev M, Pastukh V, Balczon R, Stevens T: Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin Y is a promiscuous cyclase that increases endothelial tau phosphorylation and permeability. J Biol Chem 2012, 287: 25407-25418. 10.1074/jbc.M111.301440

Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Valles J, Engel JN, Rello J: Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 521-528. 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00005

Wong-Beringer A, Wiener-Kronish J, Lynch S, Flanagan J: Comparison of type III secretion system virulence among fluoroquinolone-susceptible and -resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Clin Microbiol Infect 2008, 14: 330-336. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01939.x

Garey KW, Vo QP, Larocco MT, Gentry LO, Tam VH: Prevalence of type III secretion protein exoenzymes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from bloodstream isolates of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. J Chemother 2008, 20: 714-720. 10.1179/joc.2008.20.6.714

Sullivan E, Bensman J, Lou M, Agnello M, Shriner K, Wong-Beringer A: Risk of developing pneumonia is enhanced by the combined traits of fluoroquinolone resistance and type III secretion virulence in respiratory isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Crit Care Med 2014,42(1):48-56. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a86f

Hattemer A, Hauser A, Diaz M, Scheetz M, Shah N, Allen JP, Porhomayon J, El-Solh AA: Bacterial and clinical characteristics of health care- and community-acquired bloodstream infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57: 3969-3975. 10.1128/AAC.02467-12

El-Solh AA, Hattemer A, Hauser AR, Alhajhusain A, Vora H: Clinical outcomes of type III Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Crit Care Med 2012, 40: 1157-1163. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182377906

Lee JY, Ko KS: Mutations and expression of PmrAB and PhoPQ related with colistin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.11.027

Shime N, Sawa T, Fujimoto J, Faure K, Allmond LR, Karaca T, Swanson BL, Spack EG, Wiener-Kronish JP: Therapeutic administration of anti-PcrV F(ab′)(2) in sepsis associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Immunol 2001, 167: 5880-5886.

Frank DW, Vallis A, Wiener-Kronish JP, Roy-Burman A, Spack EG, Mullaney BP, Megdoud M, Marks JD, Fritz R, Sawa T: Generation and characterization of a protective monoclonal antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV. J Infect Dis 2002, 186: 64-73. 10.1086/341069

Faure K, Fujimoto J, Shimabukuro DW, Ajayi T, Shime N, Moriyama K, Spack EG, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sawa T: Effects of monoclonal anti-PcrV antibody on Pseudomonas aeruginosa -induced acute lung injury in a rat model. J Immune Based Ther Vaccines 2003, 1: 2. 10.1186/1476-8518-1-2

Baer M, Sawa T, Flynn P, Luehrsen K, Martinez D, Wiener-Kronish JP, Yarranton G, Bebbington C: An engineered human antibody Fab fragment specific for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV antigen has potent anti-bacterial activity. Infect Immun 2008, 77: 1083-1090.

François B, Luyt CE, Dugard A, Wolff M, Diehl JL, Jaber S, Forel JM, Garot D, Kipnis E, Mebazaa A, Misset B, Andremont A, Ploy MC, Jacobs A, Yarranton G, Pearce T, Fagon JY, Chastre J: Safety and pharmacokinetics of an anti-PcrV PEGylated monoclonal antibody fragment in mechanically ventilated patients colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa : a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2012, 40: 2320-2326. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825334f6

Milla CE, Chmiel JF, Accurso FJ, Vandevanter DR, Konstan MW, Yarranton G, Geller DE, Milla CE, Chmiel JF, Accurso FJ, Vandevanter DR, Konstan MW, Yarranton G, Geller DE, for the KB001 Study Group: Anti-PcrV antibody in cystic fibrosis: a novel approach targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection. Pediatr Pulmonol doi:10.1002/ppul 22890

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Jeanine P. Wiener-Kronish, Anesthetist-in-Chief, Henry Isaiah Dorr Professor of Anesthesia, Harvard Medical School for her critical support of his research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Relating to the content of the manuscript, the author has a patent fee from the Regents of the University of California, CA, USA.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawa, T. The molecular mechanism of acute lung injury caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: from bacterial pathogenesis to host response. j intensive care 2, 10 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-0492-2-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-0492-2-10