Abstract

Background

Previous studies have suggested that the prevalence of BRCA1 and 2 mutations in the Lebanese population is low despite the observation that the median age of breast cancer diagnosis is significantly lower than European and North American populations. We aimed at reviewing the rates and patterns of BRCA1/2 mutations found in individuals referred to the medical genetics unit at the American University of Beirut. We also evaluated the performance of clinical prediction tools.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of all individuals undergoing BRCA mutation testing from April 2011 to May 2016. To put our findings in to context, we conducted a literature review of the most recently published data from the region.

Results

Two-hundred eighty one individuals were referred for testing. The prevalence of mutated BRCA1 or 2 genes were 6 and 1.4% respectively. Three mutations accounted for 54% of the pathogenic mutations found. The BRCA1 c.131G > T mutation was found among 5/17 (29%) unrelated subjects with BRCA1 mutation and is unique to the Lebanese and Palestinian populations. For patients tested between 2014 and 2016, all patients positive for mutations fit the NCCN guidelines for BRCA mutation screening. The Manchester Score failed to predict pathogenic mutations.

Conclusion

The BRCA1 c.131G > T mutation can be considered a founder mutation in the Lebanese population detected among 5/17 (29%) of individuals diagnosed with a mutation in BRCA1 and among 7/269 families in this cohort. On review of recently published data regarding the landscape of BRCA mutations in the Middle East and North Africa, each region appears to have a unique spectrum of mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have important implications for treatment of patients diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancers as well as unaffected carriers of these mutations. Various guidelines have been established to guide physicians as to which patients should be referred for germline genetic testing. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines which are developed in the United Sates are freely available to practitioners worldwide and include broad guidelines for mutation testing based on clinical criteria without a calculation of expected mutation frequency.

A number of on-line calculators for risk of mutation assessment, based on clinical data are also available and largely used by clinical genetics specialists. The Manchester Score is a simple scoring system using basic clinical data that has been validated in several European populations to estimate an individual’s mutation risk and determine eligibility for genetic screening.

Patients with breast cancer in the Middle East, particularly in Lebanon, tend to present at a younger age with a median of 50 years compared with the median age at diagnosis of 63 years in Europe and North America [1]. In Lebanon, the prevalence of BRCA mutation were reported to be 5.7% among a cohort of patients with breast cancer meeting high-risk criteria [2]. In another study, it was found that 12.5% of referred subjects had deleterious BRCA mutation in a cohort of high risk individuals referred for genetic testing [3].

In order to further explore the landscape of BRCA mutations in the Lebanese population, we have reviewed all cases referred for BRCA mutation testing at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC), the largest tertiary referral center in the country. We also aimed at addressing the practice of referral for genetic testing and establishing whether clinician-friendly risk prediction models or guidelines could be helpful in identifying individuals meeting high-risk criteria in our population lacking access to genetic counselors [4], specifically the Manchester Score and NCCN guidelines.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of all individuals referred for BRCA mutation testing at the Medical Genetics Unit of AUBMC from April 2011 to May 2016. Data regarding family history and the frequency and characteristics of BRCA variants were collected from medical charts in order to calculate the Manchester score for this cohort (Table 1) [5]. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis was used to determine the predictive performance of the scoring system to identify those at risk of harboring a pathogenic mutation. Criteria for genetic risk evaluation according to NCCN guidelines were taken from NCCN guidelines version 1.2017 (www.nccn.org).

To put our findings in the context of the landscape of BRCA mutations in the wider Middle East, we conducted a literature review of the most recently published data from the region.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 analysis

Blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes, DNA extraction was performed using QiaAmp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen). Amplification of the target genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers designed through Primer 3 [6]. Amplified sequences were visualized on agarose gel 2% to check the efficiency of the PCR. The amplicons were then purified, sequenced and loaded on the Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystem ABI 3500). Obtained sequences were analyzed using Seqscape® v2.7 software and compared to the corresponding reference sequences (BRCA1: ncbi RefSeq NM_007294; BRCA2: ncbi RefSeq NM_000059.3). The significance of each variant found was determined referring to Clinvar database [7].

Results

Patients and disease characteristics

We reviewed the results of 281 individuals from 269 families of whom 12 subjects were known to carry a specific mutation diagnosed in an outside laboratory. 97.5% were females and 2.5% were males. The mean age of the cohort was 47.9 years (range 15–86), 208 (74.02%) patients were diagnosed to have breast (194) or ovarian (12) cancer with 2 patients presenting with both simultaneously. The mean age of patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer was 47.7 years (Table 2). Of the families referred because of a known mutation six out of twenty five (24%) of subjects were found to be positive for the specific mutation (Tables 3 and 4).

Mutations

In this cohort of 281 patients referred for BRCA testing at AUBMC, we found 17 patients with BRCA1 mutations and 4 patients with BRCA2 mutations, as seen in Table 3 and Table 4. Three common mutations (two BRCA1 and one BRCA2) accounted for 54% of the pathogenic mutations found in this cohort.

The most common BRCA1 mutation, c.131G > T was found in 5 patients and is carried by 7 Lebanese families (2 patients with family history positive of the c.131G > T mutation were found to be negative for the mutation). BRCA1 3555del4 mutation was also common, found in 4 patients and carried by 5 families. BRCA1 E720X (c.2158G > T), ranked third in frequency and was present in 2 patient and found in 3 families (Table 3). In the BRCA2 gene, the mutation IVS24-1G > A, was found in 2 patients and carried by 3 families (Table 4.) A number of Variant of Undetermined Significance (VUS) were identified in BRCA1 and 2 (Tables 3 and 4).

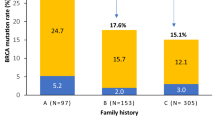

NCCN guidelines and Manchester scores

For the cohort of patients tested between 2014 and 2016 detailed family history was available. All patients positive for BRCA1 or 2 mutations fit the NCCN guidelines for BRCA mutation screening. The Manchester Score for all tested individuals was calculated, it did not discriminate between positive and negative BRCA mutation test results in this cohort with the area under the ROC curve of 0.494 (95% CI 0.349–0.639). Mean Manchester Score in patients negative for a BRCA mutation was 12.15 and that of patients positive for BRCA 1/2 mutations was 11.63 (Fig. 1).

Literature review of BRCA mutations in the MENA region

In order to put our data in to context, we reviewed the spectrum of mutations reported in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, updating a previous review published in 2015 [8].

Studies conducted in the MENA region in the past 3 years have reported a number of new mutations especially in Moroccan, Tunisian, Jordanian and Lebanese families. The most common mutations found in the MENA region are included in the Tables 5 and 6 below.

In Saudi Arabia, the BRCA1 c.4136_4137delCT and c.4524G > A were identified as the two most common mutations each found in 5 patients out of 310 enrolled in the study, accounting for 30.4% of the total BRCA mutations found in the cohort tested [9]. In Jordan, the BRCA2 c.2254_2257delGACT and Dup exon 5–11 were the 2 most common mutations each found in 4 patients out of 100 females enrolled in the study, accounting for 40% of patients presenting with the BRCA mutation [10, 11]. In Tunisia, the c.211dupA was the most common mutation found in 8 patients out of 92 from unrelated families, 29.6% of all the BRCA mutations found in this study [11]. In Morocco, several mutations were found, the most common being the c.7235insG in 2 different patients out of 40 study participants, 18.2% of the BRCA mutation carriers [12] . The BRCA1 c.798_799delTT was a common mutation in North Africa [13], however this has not been identified in studies conducted in the Middle East, namely Lebanon, Jordan or Palestine. This mutation is the only one found in several countries in the MENA region, all the other new mutations were exclusive to one country with the exception of the c.131G > T found in Lebanon and in one Palestinian patient [14] (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In a population of high-risk individuals referred for genetic testing at our institution, the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutation was 7.8%. A c.131G > T mutation was detected among 5/17 (28%) of individuals found to have a mutation in BRCA1 and among 7/28 (25%) families. The c.131G > T mutation has only recently been classified as pathogenic [7] and can be considered as a founder mutation in the Lebanese population. It is present in a relatively large number of families in our study and has previously identified in other studies conducted in Lebanon [2, 3, 15], and in a study conducted in Palestinians [14]. All individuals referred for genetic testing fit the broad NCCN guidelines however in a resource-limited health-care system where genetic testing is not usually covered by third-party payers, as is the situation in Lebanon and many other countries, identifying the individuals at highest risk for priority testing is desirable. The BRCA1 c.131G > T and c.3436_3439delTGTT along with the BRCA2 mutations account for 54% of the total BRCA mutations found in our cohort. In a resource limited environment, if the frequency of these mutations is validated in larger studies we could consider a cost-effective targeted screening test for these 3 common mutations as had been proposed in an Italian population harboring a founder mutation [16].

The Lebanese population has limited access to clinical genetics specialists and information regarding genetic testing is usually delivered by other health-care professionals such as oncologists [4]. The Manchester Score is a simple and accessible scoring system that has been used in Europe to identify individuals at high risk of harboring a BRCA mutation but has not been validated in the Middle Eastern population were the median age of diagnosis of breast cancer is significantly lower. In this cohort the Manchester score failed to discriminate between positive and negative tests. One of the limitations of this study is the size of the cohort and low absolute number of individuals tested and mutations identified. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of the data collection, although patients were prospectively assessed by a clinical geneticist at the time of testing. The relatively low rate of mutations in the BRCA1 and 2 genes in this high-risk population with breast cancer diagnosed in the relatively young, suggests that mutations in other genes may be prevalent.

To give a broader perspective on our results, we reviewed the reported mutations in the MENA region (Tables 5 and 6, Fig. 2). The founder mutation identified in our cohort seems to be unique to the Lebanese/Palestinian populations. An interesting finding is the mutual exclusivity of reported founder mutations in each of the countries in the region, with the exception of the BRCA1 c.798_799delTT identified in several North African populations.

Conclusion

In a cohort of high-risk Lebanese individuals referred for genetic testing, pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations were detected in 7.8%. While all subjects fit current NCCN guidelines for testing, the Manchester score failed to discriminate between those with positive and negative test results in this study. The BRCA1 mutation c.131G > T was detected among 5/17 (29%) of individuals found to have a pathogenic BRCA1 mutation in the cohort and can be considered a founder mutation in the Lebanese population. On review of recently published data regarding the landscape of BRCA mutations in the MENA, each region appears to have a unique spectrum of mutations. Further investigation of other genes involved in young-onset and familial breast cancer in Lebanon are ongoing.

Abbreviations

- AUBMC:

-

American University of Beirut Medical Center

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

- NCCN:

-

National comprehensive cancer network

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- VUS:

-

Variant of undetermined significance

References

El Saghir NS, Khalil MK, Eid T, El Kinge AR, Charafeddine M, Geara F, Seoud M, Shamseddine AI. Trends in epidemiology and management of breast cancer in developing Arab countries: a literature and registry analysis. Int J Surg. 2007;5(4):225–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.06.015.

El Saghir NS, Zgheib NK, Assi HA, Khoury KE, Bidet Y, Jaber SM, Charara RN, Farhat RA, Kreidieh FY, Decousus S, Romero P, Nemer GM, Salem Z, Shamseddine A, Tfayli A, Abbas J, Jamali F, Seoud M, Armstrong DK, Bignon YJ, Uhrhammer N. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ethnic Lebanese Arab women with high hereditary risk breast cancer. Oncologist. 2015;20(4):357–64. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0364.

Jalkh N, Nassar-Slaba J, Chouery E, Salem N, Uhrchammer N, Golmard L, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Bignon YJ, Megarbane A. Prevalance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in familial breast cancer patients in Lebanon. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2012;10(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-10-7.

Saroufim R, Daouk S, Abou Dalle I, Kreidieh F, Bidet Y, El Saghir N. 1411P genetic counseling, screening and risk reducing practices in patients with BRCA mutations. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5). https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx383.007.

Evans DG, Eccles DM, Rahman N, Young K, Bulman M, Amir E, Shenton A, Howell A, Lalloo F. A new scoring system for the chances of identifying a BRCA1/2 mutation outperforms existing models including BRCAPRO. J Med Genet. 2004;41(6):474–80.

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG (2012) Primer3 - new capabilities and interfaces.

ClinVar. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/. Accessed spetember 2018.

Laraqui A, Uhrhammer N, Rhaffouli HE, Sekhsokh Y, Lahlou-Amine I, Bajjou T, Hilali F, El Baghdadi J, Al Bouzidi A, Bakri Y, Amzazi S, Bignon YJ. BRCA genetic screening in middle eastern and north African: mutational spectrum and founder BRCA1 mutation (c.798_799delTT) in north African. Dis Markers. 2015, 2015:194293. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/194293.

Abulkhair O, Al Balwi M, Makram O, Alsubaie L, Faris M, Shehata H, Hashim A, Arun B, Saadeddin A, Ibrahim E. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among high-risk Saudi patients with breast Cancer. J Glob Oncol. 2018;(4):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.18.00066.

Abdel-Razeq H, Al-Omari A, Zahran F, Arun B. Germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations among high risk breast cancer patients in Jordan. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4079-1.

Riahi A, Ghourabi ME, Fourati A, Chaabouni-Bouhamed H. Family history predictors of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status among Tunisian breast/ovarian cancer families. Breast Cancer. 2017;24(2):238–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-016-0693-4.

Jouhadi H, Tazzite A, Azeddoug H, Naim A, Nadifi S, Benider A. Clinical and pathological features of BRCA1/2 tumors in a sample of high-risk Moroccan breast cancer patients. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2057-8.

Jouali F, Laarabi FZ, Marchoudi N, Ratbi I, Elalaoui SC, Rhaissi H, Fekkak J, Sefiani A. First application of next-generation sequencing in Moroccan breast/ovarian cancer families and report of a novel frameshift mutation of the BRCA1 gene. Oncol Lett. 2016;12(2):1192–6. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.4739.

Lolas Hamameh S, Renbaum P, Kamal L, Dweik D, Salahat M, Jaraysa T, Abu Rayyan A, Casadei S, Mandell JB, Gulsuner S, Lee MK, Walsh T, King MC, Levy-Lahad E, Kanaan M. Genomic analysis of inherited breast cancer among Palestinian women: genetic heterogeneity and a founder mutation in TP53. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):750–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30771.

Jalkh N, Chouery E, Haidar Z, Khater C, Atallah D, Ali H, Marafie MJ, Al-Mulla MR, Al-Mulla F, Megarbane A. Next-generation sequencing in familial breast cancer patients from Lebanon. BMC Med Genet. 2017;10(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-017-0244-7.

De Bonis M, Minucci A, Scaglione GL, De Paolis E, Zannoni G, Scambia G, Capoluongo E (2018) Capillary electrophoresis as alternative method to detect tumor genetic mutations: the model built on the founder BRCA1 c.4964_4982del19 variant. Fam Cancer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-018-0094-2.

Alhuqail AJ, Alzahrani A, Almubarak H, Al-Qadheeb S, Alghofaili L, Almoghrabi N, Alhussaini H, Park BH, Colak D, Karakas B. High prevalence of deleterious BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Arab breast and ovarian cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168(3):695–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4635-4.

Hamdi Y, Boujemaa M, Ben Rekaya M, Ben Hamda C, Mighri N, El Benna H, Mejri N, Labidi S, Daoud N, Naouali C, Messaoud O, Chargui M, Ghedira K, Boubaker MS, Mrad R, Boussen H, Abdelhak S, Consortium PEC. Family specific genetic predisposition to breast cancer: results from Tunisian whole exome sequenced breast cancer cases. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-018-1504-9.

Bu R, Siraj AK, Al-Obaisi KA, Beg S, Al Hazmi M, Ajarim D, Tulbah A, Al-Dayel F, Al-Kuraya KS. Identification of novel BRCA founder mutations in middle eastern breast cancer patients using capture and sanger sequencing analysis. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(5):1091–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30143.

Laarabi FZ, Ratbi I, Elalaoui SC, Mezzouar L, Doubaj Y, Bouguenouch L, Ouldim K, Benjaafar N, Sefiani A. High frequency of the recurrent c.1310_1313delAAGA BRCA2 mutation in the north-east of Morocco and implication for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer prevention and control. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2511-2.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was required for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the American University of Beirut Medical Center has approved this research. Due to the retrospective nature of data collection, a waiver of written consent was granted.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Farra, C., Dagher, C., Badra, R. et al. BRCA mutation screening and patterns among high-risk Lebanese subjects. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 17, 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-019-0105-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-019-0105-9