Abstract

Ovarian cancer remains the most fatal gynecologic malignancy worldwide due to delayed diagnosis as well as recurrence and drug resistance. Thus, the development of new tumor-related molecules with high sensitivity and specificity to replace or supplement existing tools is urgently needed. Cancer-testis antigens (CTAs) are exclusively expressed in normal testis tissues but abundantly found in several types of cancers, including ovarian cancer. Numerous novel CTAs have been identified by high-throughput sequencing techniques, and some aberrantly expressed CTAs are associated with ovarian cancer initiation, clinical outcomes and chemotherapy resistance. More importantly, CTAs are immunogenic and may be novel targets for antigen-specific immunotherapy in ovarian cancer. In this review, we attempt to characterize the expression of candidate CTAs in ovarian cancer and their clinical significance as biomarkers, activation mechanisms, function in malignant phenotypes and applications in immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most fatal gynecologic malignancies worldwide, with an estimated incidence of 239,000 cases and 152,000 deaths each year [1]. According to the latest data from the National Central Cancer Registry of China and The American Cancer Statistics, the ratios of new cases and deaths were 2.93% and 2.24%, respectively, in China and 2.6% and 5.06%, respectively, in America [2]. During the past decade, an increasing trend in mortality has been observed for ovarian carcinoma in China [3]. Due to delayed diagnosis, tumor recurrence and chemotherapy resistance, the 5-year survival rate of patients with advanced disease was approximately 30% [2]. Hence, there is an urgent need to explore new avenues for early diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic targets for ovarian cancer.

With the development of genome-wide sequencing in the last decade, the genomic landscape of ovarian cancer has been gradually unveiled [4, 5]. Large-scale genomic projects, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), have identified driver mutations in ovarian carcinogenesis and have provided new strategies for specific targeted therapies [4,5,6]. However, only a few mutations in these mutation-driver (mut-driver) genes are able to induce tumorigenesis [7, 8]; most of these mutations are present at low population frequencies and in a small proportion of patients [4, 8]. Notably, Vogelstein et al proposed that driver genes include not only mut-driver genes but also epi-driver genes, which are aberrantly expressed in tumors but not frequently mutated; they are altered through changes in DNA methylation or chromatin modification that persist as the tumor cell divides [8]. Among these genes, cancer-testis antigens (CTAs) or cancer-testis (CT) genes have attracted particular attention due to their restricted expression patterns and immunogenicity [9, 10].

CTAs consist of a cluster of genes exclusively expressed in normal testis tissues, yet abundant levels are found in several types of tumor tissues. The role of CT genes in spermatogenesis and tumorigenesis is an interesting issue. Reactivation of normally silent CT gene expression in cancer cells may confer some of the central characteristics of tumor formation and progression, including demethylation, angiogenesis induction, major histocompatibility complex downregulation (immune evasion), and chorionic gonadotropin expression [10]. The similarity between gametogenesis and tumorigenesis includes the following: immortalization of primordial germ cells and transformation of tumor cells; ploidy cycles in meiosis and aneuploidy in tumor cells; migration of primordial germ cells and metastasis of tumor cells. Emerging studies have suggested that aberrant expression of CTAs may drive soma-to-germline transformation and result in tumorigenesis and tumor progression [11, 12]. Owing to their immunogenic properties, these germ-line genes may represent novel targets for cancer immunotherapy [13]. Indeed, several CTAs have become a major focus for the development of vaccine-based clinical trials in recent years. For example, combined analysis of NY-ESO-1-based trials revealed that patients with NY-ESO-1-positive tumors who received immunotherapy exhibited a 2-year overall survival (OS) advantage compared with those with NY-ESO-1-positive tumors who did not receive vaccination [14]. Given the increasing number of identified CT genes and the recent research advances in ovarian cancer, we herein summarize the characteristics, clinical applications, potential activation mechanisms and function of CTAs in ovarian cancer.

Expression of CT genes in ovarian cancer

CTAs are classified into two categories: CT-X antigens located on the X chromosome and non-X CTAs located on autosomes [15]. The first cancer antigen MAGE-A1 was recognized by autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a melanoma patient [16, 17]. Subsequent advances in biotechnology have enabled scientists to explore more cancer antigen subgroups expressed in gametogenic tissues and a variety of tumors, including multiple myeloma [18] and ovarian cancer [19]. The list of identified CT genes has expanded to approximately 250 genes in the CT database (http://www.cta.lncc.br) [20]. Based on multiple independent large databases, including Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx), and human proteomic and TCGA data, our group recently systematically explored the molecular landscape of CT genes in 19 cancer types [9]. CTA family members in ovarian cancer reported to date include MAGE genes, NY-ESO-1, SSX, and CT45, which are categorized as CT-X antigens, and BORIS, PRAME, PIWIL, and AKAP3/4, which are categorized as non-X CTAs. A growing number of studies have focused on the identification of CTAs in ovarian cancer. The characteristics of CTAs are summarized in Table 1.

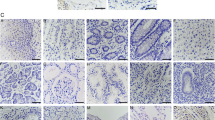

As one classical type of CT gene, the expression levels of MAGE genes in ovarian cancer have been widely investigated, e.g., the frequency of MAGE-A1 mRNA expression was found to be 20.7% among 58 ovarian cancer tissues [19]. Moreover, Daudi et al examined MAGE expression in 400 epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) tissues by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) and found that at least one of five MAGE antigens (MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3, MAGE-A4, MAGE-A10 and MAGE-C1) was expressed in approximately 78% of EOC patients [21]. Another study further demonstrated that MAGE-A4 serum levels were significantly increased in ovarian cancer patients compared with those with benign diseases, and the MAGE-A4 protein was expressed in 22% of primary ovarian cancer patients [22]. One interesting finding is that MAGE-A3/6 protein was found to be present on plasma-derived exosomes from all ovarian cancer patients assessed but not on those from benign tumors or healthy controls [23]. Coincidentally, Hofmann and colleagues detected BAGE, MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3 and GAGE1/-2 mRNAs in peritoneal fluid from ovarian cancer patients using multiplex RT-PCR analysis, with the combination of the four markers exhibiting increased diagnostic sensitivity of 94% compared with cytomorphology alone [24].

Odunsi et al reported that either NY-ESO-1 or LAGE-1 was expressed in approximately 50% of 107 EOC specimens [25], and subsequent CTA analysis in a large cohort of ovarian cancer patients (n=1002) revealed NY-ESO-1 expression by any method in 41% of tumors [14]. In addition, aberrant expression of SSX-1, SSX-2, or SSX-4 was identified in 26% of ovarian tumor specimens, and SSX-1, SSX-2, and SSX-4 expression was detected in 2.5%, 10%, and 16% of 120 EOC specimens, respectively [26]. Among 219 ovarian cancer cases included in a tissue microarray, CT45 was expressed in 82 samples (37%), with the majority of cases showing moderate (++) to strong (+++) expression [27]. Furthermore, high AKAP3 mRNA expression was observed in 43/74 (58%) of ovarian cancer specimens [28]. Although AKAP4 mRNA and protein were not expressed in 21 matched adjacent non-cancerous tissues, they were detected in 89% (34/38) of ovarian carcinoma tissues [29]. One study reported extensive distribution of SPAG9 mRNA and protein in 90% (18/20) of EOC tissue specimens [30]. CT45 is reportedly not expressed in normal ovary samples but is activated in a significant proportion of EOC specimens (25%), with marked expression in serous EOC but not in non-serous EOC [31]. It has also been reported that sperm protein antigen 17 (Sp17) is expressed in adenocarcinoma cells of all epithelial ovarian cancer subtypes and in 43% (30/70) of EOC cases [32]. Recently, findings from Garcia-Soto et al suggest that CT genes (a panel of 20 CT genes) are expressed in 95% of EOC tumor specimens, with a mean number of 4.5 [33].

Notably, emerging evidence indicates that CT genes are preferentially expressed in a cluster, indicating that these genes may share common regulatory elements and possible functional relevance. One study suggested that NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1 are dually expressed in 11% of epithelial ovarian tumor specimens as well as the SKOV3 cell line [25]. MAGE-A4 exhibits a relatively high expression frequency and plays a central role in the co-expression of other MAGE antigens [21]. MAGE-C1 expression and co-expression of CT genes are significantly correlated with the grade of endometrioid ovarian cancer and the histological subtype [34], and analysis of Oncomine datasets has confirmed that CT45 is co-expressed with other CT genes in EOC, including MAGE and GAGE genes [31]. Importantly, a subset of CT genes shows distinct expression in specific pathological subtypes or different stages of ovarian cancer; some CT genes are likely expressed in serous histologic subtypes. The majority of MAGE-mRNA-positive ovarian tumors are histologically classified as surface-epithelial-stromal tumors, particularly serous adenocarcinomas [19]. One study found that AKAP4 was expressed in serous adenocarcinoma and serous papillary carcinoma but not in endometrioid adenocarcinoma or adenofibroma [29]. Patients with late-stage or high-grade EOC often express increased CT45 levels [31]. Expression of TRAG3 is also increased after the initiation of chemotherapy following initial surgery [36]. Taken together, because of their unique characteristics, CT genes are promising biomarkers for diagnosing ovarian cancer and assessing tumor aggressiveness.

Tumor progression and prognosis

An increasing number of studies have reported correlations between CT genes and tumor progression and prognosis. Regarding MAGE members, expression of MAGE-A1 and MAGE-A3 correlates with tumor differentiation and clinical stage in ovarian cancer [37]; MAGE-A1 and MAGE-A10 expression is also significantly associated with poor progression-free survival (PFS) in EOC [21]. MAGE-A4 is a reliable prognostic factor for serous carcinoma patients [38]. MAGE-A9 expression was also found to be significantly associated with high histological grade, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, CA-125 level and metastasis. In addition, patients with MAGE-A9 expression exhibited poor OS [39]. Consistently, one study examined the prognostic significance of MAGE-A family expression in EOC patients and showed MAGE-A expression to be associated with pathological type, FIGO stage, and pre-operative serum CA125 level. Furthermore, the OS of EOC patients with MAGE-A family expression was significantly reduced compared with patients negative for MAGE-A expression [40]. In addition, the expression levels of MAGE-As and each individual MAGE-A gene in peripheral blood were associated with low OS in ovarian cancer patients [41]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results for serum MAGE antigen-specific antibodies revealed that the presence of a humoral immune response to any MAGE antigen predicted poor OS [21].

Recently, Szender et al first demonstrated the association between NY-ESO-1 expression and an aggressive ovarian cancer phenotype, reporting that NY-ESO-1+ patients had more serous histotypes and grade 3 tumors, exhibited a higher stage and were less likely to have a complete response to initial therapy. A trend toward reduced PFS and significantly reduced OS has been noted among NY-ESO-1+ patients [14]. Similarly, patients expressing AKAP-3 mRNA exhibit a significantly poorer OS than patients lacking AKAP-3 expression [28]. Consistently, AKAP-3 is primarily expressed in advanced-stage and poorly differentiated cancers [42]. Furthermore, PIWI proteins are upregulated in EOC tissues and associated with tumor metastasis [43]. Zhang et al found CT45 to be activated only in late-stage and high-grade disease, and increased CT45 expression was correlated with reduced OS and DFS in EOC [31]. Taken together, these findings indicate that CT genes have the potential to serve as prognostic markers for ovarian cancer patients.

Molecular mechanisms of CT gene expression

Based on the tendency of co-expression noted in cancers, CT genes are thought to share a common mechanism of regulation at the transcriptional level [44]. A body of work indicates that epigenetic regulation is a key mechanism in the transcriptional regulation of CT genes [45]. According to the literature, the mechanism of CTA activation includes the following several categories.

DNA hypomethylation in CT gene activation

It is reported that DNA methylation plays a dominant role in the epigenetic hierarchy governing CT gene expression. DNA hypomethylation coordinately affects CT gene promoters in EOC and correlates with advanced-stage disease. One study provided initial evidence that activation of MAGE-A1 in cancer cells is caused by promoter DNA hypomethylation [46]. After exposure to the DNA demethylating agent 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (DAC), human ovarian cancer cell lines display an pattern of upregulated for many CT genes [47, 48]. CT genes are coordinately expressed in EOC, and this expression pattern is associated with promoter DNA hypomethylation [49]. Additionally, Yao et al utilized sodium bisulfite sequencing of genomic DNA to provide direct evidence that methylation of TRAG-3 exon 2 and the promoter suppresses its transcription [50]. Intriguingly, several studies have suggested that expression levels of CT genes correlate with global genomic DNA hypomethylation in cancers [51, 52]. For example, Woloszynska-Read and co-workers reported that in ovarian cancer, DNA hypomethylation drives expression of BORIS, which is partly determined by the global DNA methylation status [51]. Similar interconnections have been observed for NY-ESO-1, MAGE genes and some other CT genes. Woloszynska-Read et al reported that both intertumor and intratumor NY-ESO-1 expression heterogeneity is associated with promoter methylation and global DNA methylation in EOC [52]. MAGEA11 expression is also associated with promoter and global DNA hypomethylation and activation of other CT genes [53]. And a link between promoter DNA methylation alterations and CT45 expression was validated in EOC in clinical samples and EOC cell models [31]. CT45 hypomethylation shows a strong correlation with LINE-1 hypomethylation, which is a good indicator of the level of global DNA methylation [31]. All evidence to date suggests that expression of these genes in tumors is dependent on aberrant DNA hypomethylation. Moreover, Ahluwalia et al identified DNA methyltransferase genes as a key component of the DNA methylation process; these genes are upregulated in cancers and maintain the state of methylation [54]. In addition, DNA methylation regulates nucleosome occupancy and participates in CT gene activation. Indeed, DNA methylation regulates nucleosome occupancy at the -1 position of MAGEA11, which was correlated with methylation of a Ets site and involved in the repression of MAGEA11 activity [53]. Thus, it appears that DNA methylation may cooperate with sequence-specific transcription factors to regulate gene expression.

Histone modification and modulation of CT gene expression

Demethylation and re-expression of CT genes in tumors is generally correlated with losses in repressive histone marks and gains in activating histone marks [55, 56]. Treatment of A2780/cp70 with DAC and a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor resulted in a marked increase in expression of epigenetically silenced MAGE-A1 both in vitro and in vivo [57]. Woloszynska-Read et al observed that genetic disruption of DNA methylation in human cancer cells induces BORIS expression and an altered histone H3 modification pattern at the BORIS promoter [51]. Consistently, multiple BORIS isoforms are activated synergistically by DAC + trichostatin A (TSA) treatment, indicating that both DNA hypomethylation and histone acetylation are sufficient for BORIS isoform expression in EOC cells [58]. Regardless, studies on the effect of histone modification on CT gene expression are limited, and most studies thus far have typically applied a pharmacological approach. Evidence based on direct detection of specific histone modifications in ovarian cancer tissues is not currently available. Further studies are needed to provide clarity on this topic.

Effect of copy number alteration (CNA) on activation of CT genes

Copy number aberrations are identified as remarkable molecular alterations in EOC and have the ability to alter gene expression [5]. Based on cBioPortal analysis of TCGA data [59], one recent study demonstrated that CNA was correlated with PRAME expression in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). Notably, the proportion of PRAME amplification was low compared with the high prevalence of increased PRAME expression [60]. Another study reported that among TCGA HGSOC data, CT45 expression did not correlate with copy number status [31]. Therefore, CNA may have a minor contribution to the observed increased expression of CT genes in ovarian cancer.

Effect of TP53 mutation on CT gene expression

TP53 mutations are present in almost all HGSOCs [5, 7], a finding that has prompted investigation into whether a relationship exists between CT gene expression and TP53 mutation status in serous ovarian cancer. Devor et al presented evidence that PLAC1 transcriptional repression occurs in serous ovarian carcinomas only in the presence of wild-type TP53, whereas mutant or absent TP53 protein de-represses PLAC1 transcription [61]. These authors proposed that the inability of mutant TP53 to occupy the TP53 binding site in the PLAC1 P1 promoter allowed transcription to occur [61]. By directly binding to the promoter or interacting with the transcription factor Sp1, expression of wild-type TP53 protein represses the activity of all BORIS promoters [62]. Therefore, as a gatekeeper of genome instability, TP53 mutations may contribute to activation of CT genes. Another comprehensive study demonstrated CT genes to be mutually exclusively correlated with somatic mutations in significantly mutated genes (SMG) in cancers, indicating that these CT genes may function as novel drivers that complement known mut-driver genes [9].

CT gene function in ovarian cancer

Based on a multidimensional functional genomics approach, Maxfield et al uncovered that multiple CT genes play an obligatory role in multiple hallmarks of cancer and function as pathological drivers of major pathways, including HIF, WNT and TGFb signaling [63]. Cellular switching from a specific somatic designation to acquisition of a germline cell-like state (soma-to-germline transition) is the key feature of oncogenesis, and CT genes play a functional role in initiating and maintaining oncogenesis [64].

Although the function of many CT genes in ovarian cancer remains unclear, it appears that these genes may exert oncogenic functions in tumorigenesis and progression. Heat shock protein 70-2 (HSP70-2) is required for the formation of an active CDC2/Cyclin B complex in meiosis I division during spermatogenesis [65]. Moreover, HSP70-2 knock-out mice fail to complete meiosis [65]. Several reports have demonstrated that HSP70-2 is involved in cellular proliferation and the early spread of various malignancies, including breast cancer [66] and ovarian cancer [67]. Using in vitro and in vivo human ovarian xenograft mouse models, one recent study demonstrated that ablation of HSP70-2 resulted in cell cycle arrest, onset of senescence and apoptosis and inhibited cell proliferation, cell viability and colony formation in EOC [67]. In addition, HSP70-2-depleted EOC cells exhibit downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins and increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes, subsequently leading to upregulation of cytochrome-C, caspase 3, caspase 7 and caspase 9 [67]. Therefore, HSP70-2 may promote malignancy in EOC cells.

AKAPs comprise a family of scaffolding proteins that anchor different proteins and tether protein kinase A (PKA) at specific locations to restrict enzymatic activities [68]. Some of the AKAPs considered to be CT genes in ovarian cancer include AKAP3 [42] and AKAP4 [29]. These proteins typically bind to the regulatory subunit RI or RII domain of PKA and cooperatively terminate cAMP signaling [68]. Notably, PKA activity and anchoring are required for ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion [69]. Kumar et al demonstrated that AKAP4 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation and viability, induces cell cycle arrest, and increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, DNA damage and apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells and reduces tumor growth in an ovarian cancer xenograft model [70]. Furthermore, AKAP4 knockdown inhibits wound healing and reduces metastatic markers in ovarian cancer cells [70].

The primary function of Sp17, a protein originally reported to be expressed exclusively in the testis, is binding to the zona pellucida [71]. One study reported that the metastatic ascitic fluid from eight EOC patients was positive for Sp17 [32], and two others consistently found that migration of ovarian cancer cells (HO-8910) was substantially enhanced after Sp17 overexpression [32, 72]. Several reports have demonstrated that Sp17 plays an important role in cell-cell adhesion and/or cell migration in transformed, lymphocytic, and hematopoietic cells, possibly through its interaction with extracellular heparin sulfate or binding to AKAP3 [73, 74]. Another study demonstrated that an Sp17-based vaccine induced an enduring defense response against ovarian cancer development in C57BL/6 mice with ID8 cells following prophylactic and therapeutic treatments [75].

HORMAD1, a meiosis I checkpoint protein that is expressed during gonadal development, is upstream of ATM kinase (a serine-threonine protein kinase) activation [76]. In ovarian cancer cells, HORMAD1 siRNA enhanced docetaxel-induced apoptosis and reduced invasive and migratory capacities. In addition, HORMAD1 targeting in vivo with siRNA-DOPC significantly reduced tumor weight and ascites production, in association with substantial reductions in angiogenesis and VEGF and NF-κB levels [77]. Collectively, re-expression of CT genes results in crucial biological activities in ovarian cancer.

Chemotherapy resistance

Chemotherapy is widely applied for the treatment of ovarian cancer, but drug resistance remains a major obstacle for success. Indeed, some evidence suggests that drug resistance is associated with increased expression of a variety of CT genes. One study demonstrated that MAGE gene families are overexpressed in some drug-resistant ovarian cell lines and that transfection of MAGE-A2 and MAGE-A6 into a sensitive cell line can facilitate cell growth and induce paclitaxel and doxorubicin resistance [78]. Another study indicated that overexpression of MAGE-A3 correlates with a doxorubicin-resistant phenotype [79]. In addition, MAGE-C1 expression was associated with platinum-sensitive disease and clinical response [21]. For other CT genes, high PLU-1 levels are significantly associated with chemotherapy resistance, and PLU-1 is an independent factor for chemotherapy resistance in patients with EOC [80]. TRAG-3, which was originally identified as a Taxol resistance-associated gene from an ovarian carcinoma cell line, is associated with the chemotherapy-resistant and neoplastic phenotype [81]. Notably, Sp17 overexpression was found to reduce the chemosensitivity of ovarian carcinoma cells to carboplatin and cisplatin [32, 36]. Importantly, PIWIL2 is required for maintaining the equilibrium between euchromatin and heterochromatin in response to cisplatin treatment in mammalian cells, and increased levels of PIWIL2 expression in human ovarian cancer cell lines (CDDP and 2008C13) facilitate cisplatin resistance, likely through enhanced repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage [82]. In a pan-genomic siRNA screen for modifiers of chemo-responsiveness, Whitehurst et al. identified that OY-TES-1, a specifier of paclitaxel resistance, is necessary and sufficient for paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cell lines and ovarian tumor explants [83]. Although the researchers hypothesized that overexpression of these genes contributes to the chemo-resistant phenotype via co-expression with multidrug resistance genes [50, 78, 80], the detailed mechanism by which CT genes induce drug resistance requires further investigation.

Application in immunotherapy

In addition to traditional operation or chemotherapy, a subset of burgeoning cure modalities, including target therapy and radiation therapy, aims to abrogate tumor cells, and CT genes may represent a class of potential targets for tumor immunotherapy due to their specific expression patterns and oncogenic function. These genes also respond to T-cells and subsequently stimulate the immune response. Some NY-ESO-1 clinical trials thus far have been carried out in ovarian cancer patients, and the indicated NY-ESO-1 targeted therapy has a potential clinical benefit [13]. For example, the antigen was able to induce cellular and humoral immune responses in a high proportion of patients with NY-ESO-1 expression. Odunsi et al reported that NY-ESO-1157–170 with dual HLA class I and II specificities should elicit integrated Ab, HLA-DP4-restricted CD4+ T cell and HLA-A2 and A24-restricted CD8+ T cell responses in ovarian cancer patients [84]. Seven years later, these researchers described an encouraging result that a combination of decitabine and the NY-ESO-1 vaccine resulted in disease stabilization or a partial clinical response in relapsed EOC patients [85] Decitabine may enhance the response to the NY-ESO-1 vaccine by promoting CTA promoter hypomethylation and immunity [86,87,88]. This regimen complements standard second-line chemotherapy. Another CT antigen vaccine undergoing assessment in clinical trials is MAGE-A3, which is frequently expressed in various cancers [89]. However, there are currently no ongoing clinical studies of MAGE-A3-directed anti-ovarian cancer immunotherapies. In addition, Chiriva-Internati et al demonstrated that HLA class I-restricted Sp17-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) enable autologous tumor killing through the perforin pathway [90, 91]. To date, two studies have confirmed the different formulations of the Sp17 vaccine in a murine ovarian cancer model. One vaccine was CpG-adjuvated Sp17, which inhibited tumor growth and prolonged the OS of vaccinated mice [92]. The other vaccine was the nanoparticle-based hSp17111–142 peptide, which induced mixed Th1/Th2 responses and subsequently stimulated B-cell production of IgG1 and IgG2a. This vaccine exhibited advantages leading to the promotion of immunogenicity and strong cross-reactivity of the antibody [93]. Nonetheless, clinical trials on ovarian cancer patients must be initiated to verify whether the Sp17 vaccine exhibits treatment efficacy in humans.

Conclusions

In summary, our current understanding of the expression, mechanism and function of CT genes in ovarian cancer is still largely in the early stages. Given advances in whole-genome sequencing and shared large databases, such as Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and TCGA, further studies on the characteristic features of CT genes in testis and ovarian cancers are warranted to provide insight into similarities and differences. More importantly, the unique properties of CT genes, such as their inherent immunogenicity and heterogeneity in their expression patterns, indicate that they have great potential for clinical application. To better understand the immunological processes of CT genes in ovarian cancer, more clinical trials directed against CT antigens and the development of combination therapies are needed. Such efforts will contribute to targeted immunotherapies for ovarian cancer.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Cancer-testis

- CTAs:

-

Cancer-testis antigens

- DAC:

-

5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine

- EOC:

-

Epithelial ovarian cancer

- FIGO:

-

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus.

- GTEx:

-

The Genotype-Tissue Expression

- HDAC:

-

Histone deacetylase

- HGSOC:

-

High-grade serous ovarian cancer

- HSP70-2:

-

Heat shock protein 70-2

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- NER:

-

Nucleotide excision repair

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PKA:

-

Protein kinase A

- RT-PCR:

-

reverse transcription-PCR

- SMG:

-

Significantly mutated genes

- Sp17:

-

Sperm protein antigen 17

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30.

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32.

Zhao S, Bellone S, Lopez S, Thakral D, Schwab C, English DP, et al. Mutational landscape of uterine and ovarian carcinosarcomas implicates histone genes in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(43):12238–43.

Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011; 474(7353):609-15.

Dong F, Davineni PK, Howitt BE, Beck AH. A BRCA1/2 Mutational Signature and Survival in Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(11):1511–6.

Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–9.

Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–58.

Wang C, Gu Y, Zhang K, Xie K, Zhu M, Dai N, et al. Systematic identification of genes with a cancer-testis expression pattern in 19 cancer types. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10499.

Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. Cancer testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(8):615–25.

Feichtinger J, Larcombe L, McFarlane RJ. Meta-analysis of expression of l(3)mbt tumor-associated germline genes supports the model that a soma-to-germline transition is a hallmark of human cancers. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(10):2359–65.

McFarlane RJ, Feichtinger J, Larcombe L. Germline meiotic genes in cancer: new dimensions. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(6):791–2.

Odunsi K. Immunotherapy in ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_8):viii1–7.

Szender JB, Papanicolau-Sengos A, Eng KH, Miliotto AJ, Lugade AA, Gnjatic S, et al. NY-ESO-1 expression predicts an aggressive phenotype of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(3):420–5.

Odunsi K, Matsuzaki J, Karbach J, Neumann A, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Miller A, et al. Efficacy of vaccination with recombinant vaccinia and fowlpox vectors expressing NY-ESO-1 antigen in ovarian cancer and melanoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(15):5797–802.

Chaux P, Luiten R, Demotte N, Vantomme V, Stroobant V, Traversari C, et al. Identification of five MAGE-A1 epitopes recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes obtained by in vitro stimulation with dendritic cells transduced with MAGE-A1. J Immunol. 1999;163(5):2928–36.

van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991;254(5038):1643–7.

de Carvalho F, Vettore AL, Colleoni GW. Cancer/Testis Antigen MAGE-C1/CT7: new target for multiple myeloma therapy. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:257695.

Yamada A, Kataoka A, Shichijo S, Kamura T, Imai Y, Nishida T, et al. Expression of MAGE-1, MAGE-2, MAGE-3/-6 and MAGE-4a/-4b genes in ovarian tumors. Int J Cancer. 1995;64(6):388–93.

Almeida LG, Sakabe NJ, de Oliveira AR, Silva MC, Mundstein AS, Cohen T, et al. CTdatabase: a knowledge-base of high-throughput and curated data on cancer-testis antigens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D816–9.

Daudi S, Eng KH, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Morrison C, Miliotto A, Beck A, et al. Expression and immune responses to MAGE antigens predict survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104099.

Kawagoe H, Yamada A, Matsumoto H, Ito M, Ushijima K, Nishida T, et al. Serum MAGE-4 protein in ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;76(3):336–9.

Szajnik M, Derbis M, Lach M, Patalas P, Michalak M, Drzewiecka H, et al. Exosomes in Plasma of Patients with Ovarian Carcinoma: Potential Biomarkers of Tumor Progression and Response to Therapy. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale). 2013; Suppl 4:3.

Hofmann M, Ruschenburg I. mRNA detection of tumor-rejection genes BAGE, GAGE, and MAGE in peritoneal fluid from patients with ovarian carcinoma as a potential diagnostic tool. Cancer. 2002;96(3):187–93.

Odunsi K, Jungbluth AA, Stockert E, Qian F, Gnjatic S, Tammela J, et al. NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1 cancer-testis antigens are potential targets for immunotherapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):6076–83.

Valmori D, Qian F, Ayyoub M, Renner C, Merlo A, Gnjatic S, et al. Expression of synovial sarcoma X (SSX) antigens in epithelial ovarian cancer and identification of SSX-4 epitopes recognized by CD4+ T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(2):398–404.

Chen YT, Hsu M, Lee P, Shin SJ, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Odunsi K, et al. Cancer/testis antigen CT45: analysis of mRNA and protein expression in human cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(12):2893–8.

Sharma S, Qian F, Keitz B, Driscoll D, Scanlan MJ, Skipper J, et al. A-kinase anchoring protein 3 messenger RNA expression correlates with poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(1):183–8.

Agarwal S, Saini S, Parashar D, Verma A, Sinha A, Jagadish N, et al. The novel cancer-testis antigen A-kinase anchor protein 4 (AKAP4) is a potential target for immunotherapy of ovarian serous carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(5):e24270.

Garg M, Chaurasiya D, Rana R, Jagadish N, Kanojia D, Dudha N, et al. Sperm-associated antigen 9, a novel cancer testis antigen, is a potential target for immunotherapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(5):1421–8.

Zhang W, Barger CJ, Link PA, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Miller A, Akers SN, et al. DNA hypomethylation-mediated activation of Cancer/Testis Antigen 45 (CT45) genes is associated with disease progression and reduced survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. Epigenetics. 2015;10(8):736–48.

Li FQ, Han YL, Liu Q, Wu B, Huang WB, Zeng SY. Overexpression of human sperm protein 17 increases migration and decreases the chemosensitivity of human epithelial ovarian cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:323.

Garcia-Soto AE, Schreiber T, Strbo N, Ganjei-Azar P, Miao F, Koru-Sengul T, et al. Cancer-testis antigen expression is shared between epithelial ovarian cancer tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(3):413–9.

Zimmermann AK, Imig J, Klar A, Renner C, Korol D, Fink D, et al. Expression of MAGE-C1/CT7 and selected cancer/testis antigens in ovarian borderline tumours and primary and recurrent ovarian carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2013;462(5):565–74.

Tammela J, Uenaka A, Ono T, Noguchi Y, Jungbluth AA, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, et al. OY-TES-1 expression and serum immunoreactivity in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2006;29(4):903–10.

Materna V, Surowiak P, Kaplenko I, Spaczynski M, Duan Z, Zabel M, et al. Taxol-resistance-associated gene-3 (TRAG-3/CSAG2) expression is predictive for clinical outcome in ovarian carcinoma patients. Virchows Arch. 2007;450(2):187–94.

Zhang S, Zhou X, Yu H, Yu Y. Expression of tumor-specific antigen MAGE. GAGE and BAGE in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:163.

Yakirevich E, Sabo E, Lavie O, Mazareb S, Spagnoli GC, Resnick MB. Expression of the MAGE-A4 and NY-ESO-1 cancer-testis antigens in serous ovarian neoplasms. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(17):6453–60.

Xu Y, Wang C, Zhang Y, Jia L, Huang J. Overexpression of MAGE-A9 Is Predictive of Poor Prognosis in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12104.

Sang M, Wu X, Fan X, Lian Y, Sang M. MAGE-A family serves as poor prognostic markers and potential therapeutic targets for epithelial ovarian cancer patients: a retrospective clinical study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(6):480–4.

Sang M, Wu X, Fan X, Sang M, Zhou X, Zhou N. Multiple MAGE-A genes as surveillance marker for the detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with ovarian cancer. Biomarkers. 2014;19(1):34–42.

Hasegawa K, Ono T, Matsushita H, Shimono M, Noguchi Y, Mizutani Y, et al. A-kinase anchoring protein 3 messenger RNA expression in ovarian cancer and its implication on prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(1):86–90.

Chen C, Liu J, Xu G. Overexpression of PIWI proteins in human stage III epithelial ovarian cancer with lymph node metastasis. Cancer Biomark. 2013;13(5):315–21.

De Smet C, Lurquin C, Lethe B, Martelange V, Boon T. DNA methylation is the primary silencing mechanism for a set of germ line- and tumor-specific genes with a CpG-rich promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(11):7327–35.

Karpf AR. A potential role for epigenetic modulatory drugs in the enhancement of cancer/germ-line antigen vaccine efficacy. Epigenetics. 2006;1(3):116–20.

De Smet C, De Backer O, Faraoni I, Lurquin C, Brasseur F, Boon T. The activation of human gene MAGE-1 in tumor cells is correlated with genome-wide demethylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(14):7149–53.

Adair SJ, Hogan KT. Treatment of ovarian cancer cell lines with 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine upregulates the expression of cancer-testis antigens and class I major histocompatibility complex-encoded molecules. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(4):589–601.

Siebenkas C, Chiappinelli KB, Guzzetta AA, Sharma A, Jeschke J, Vatapalli R, et al. Inhibiting DNA methylation activates cancer testis antigens and expression of the antigen processing and presentation machinery in colon and ovarian cancer cells. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179501.

Woloszynska-Read A, Zhang W, Yu J, Link PA, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Collamat G, et al. Coordinated cancer germline antigen promoter and global DNA hypomethylation in ovarian cancer: association with the BORIS/CTCF expression ratio and advanced stage. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2170–80.

Yao X, Hu JF, Li T, Yang Y, Sun Z, Ulaner GA, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the taxol resistance-associated gene TRAG-3 in human tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;151(1):1–13.

Woloszynska-Read A, James SR, Link PA, Yu J, Odunsi K, Karpf AR. DNA methylation-dependent regulation of BORIS/CTCFL expression in ovarian cancer. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:21.

Woloszynska-Read A, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Yu J, Odunsi K, Karpf AR. Intertumor and intratumor NY-ESO-1 expression heterogeneity is associated with promoter-specific and global DNA methylation status in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(11):3283–90.

James SR, Cedeno CD, Sharma A, Zhang W, Mohler JL, Odunsi K, et al. DNA methylation and nucleosome occupancy regulate the cancer germline antigen gene MAGEA11. Epigenetics. 2013;8(8):849–63.

Ahluwalia A, Hurteau JA, Bigsby RM, Nephew KP. DNA methylation in ovarian cancer. II. Expression of DNA methyltransferases in ovarian cancer cell lines and normal ovarian epithelial cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82(2):299–304.

Rao M, Chinnasamy N, Hong JA, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Xi S, et al. Inhibition of histone lysine methylation enhances cancer-testis antigen expression in lung cancer cells: implications for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(12):4192–204.

Link PA, Gangisetty O, James SR, Woloszynska-Read A, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, et al. Distinct roles for histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP in cancer germ-line antigen gene regulation in human cancer cells and murine embryonic stem cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(6):851–62.

Steele N, Finn P, Brown R, Plumb JA. Combined inhibition of DNA methylation and histone acetylation enhances gene re-expression and drug sensitivity in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(5):758–63.

Link PA, Zhang W, Odunsi K, Karpf AR. BORIS/CTCFL mRNA isoform expression and epigenetic regulation in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Immun. 2013;13:6.

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–4.

Zhang W, Barger CJ, Eng KH, Klinkebiel D, Link PA, Omilian A, et al. PRAME expression and promoter hypomethylation in epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(29):45352–69.

Devor EJ, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Warrier A, Reyes HD, Ibik NV, Schickling BM, et al. p53 mutation status is a primary determinant of placenta-specific protein 1 expression in serous ovarian cancers. Int J Oncol. 2017;50(5):1721–8.

Renaud S, Pugacheva EM, Delgado MD, Braunschweig R, Abdullaev Z, Loukinov D, et al. Expression of the CTCF-paralogous cancer-testis gene, brother of the regulator of imprinted sites (BORIS), is regulated by three alternative promoters modulated by CpG methylation and by CTCF and p53 transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(21):7372–88.

Maxfield KE, Taus PJ, Corcoran K, Wooten J, Macion J, Zhou Y, et al. Comprehensive functional characterization of cancer-testis antigens defines obligate participation in multiple hallmarks of cancer. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8840.

McFarlane RJ, Wakeman JA. Meiosis-like Functions in Oncogenesis: A New View of Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):5712–6.

Zhu D, Dix DJ, Eddy EM. HSP70-2 is required for CDC2 kinase activity in meiosis I of mouse spermatocytes. Development. 1997;124(15):3007–14.

Jagadish N, Agarwal S, Gupta N, Fatima R, Devi S, Kumar V, et al. Heat shock protein 70-2 (HSP70-2) overexpression in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):150.

Gupta N, Jagadish N, Surolia A, Suri A. Heat shock protein 70-2 (HSP70-2) a novel cancer testis antigen that promotes growth of ovarian cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7(6):1252–69.

Skroblin P, Grossmann S, Schafer G, Rosenthal W, Klussmann E. Mechanisms of protein kinase A anchoring. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010;283:235–330.

McKenzie AJ, Campbell SL, Howe AK. Protein kinase A activity and anchoring are required for ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26552.

Kumar V, Jagadish N, Suri A. Role of A-Kinase anchor protein (AKAP4) in growth and survival of ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(32):53124–36.

Frayne J, Hall L. A re-evaluation of sperm protein 17 (Sp17) indicates a regulatory role in an A-kinase anchoring protein complex, rather than a unique role in sperm-zona pellucida binding. Reproduction. 2002;124(6):767–74.

Liu Q, Li FQ, Han YL, Wang LK, Hou YY. Aberrant expression of sperm protein 17 enhances migration of ovarian cancer cell line HO-8910. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2008;14(11):982–6.

Lacy HM, Sanderson RD. Sperm protein 17 is expressed on normal and malignant lymphocytes and promotes heparan sulfate-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Blood. 2001;98(7):2160–5.

Arnaboldi F, Menon A, Menegola E, Di Renzo F, Mirandola L, Grizzi F, et al. Sperm protein 17 is an oncofetal antigen: a lesson from a murine model. Int Rev Immunol. 2014;33(5):367–74.

Song JX, Cao WL, Li FQ, Shi LN, Jia X. Anti-Sp17 monoclonal antibody with antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity activities against human ovarian cancer cells. Med Oncol. 2012;29(4):2923–31.

Shin YH, Choi Y, Erdin SU, Yatsenko SA, Kloc M, Yang F, et al. Hormad1 mutation disrupts synaptonemal complex formation, recombination, and chromosome segregation in mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(11):e1001190.

Shahzad MM, Shin YH, Matsuo K, Lu C, Nishimura M, Shen DY, et al. Biological significance of HORMA domain containing protein 1 (HORMAD1) in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2013;330(2):123–9.

Duan Z, Duan Y, Lamendola DE, Yusuf RZ, Naeem R, Penson RT, et al. Overexpression of MAGE/GAGE genes in paclitaxel/doxorubicin-resistant human cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(7):2778–85.

Bertram J, Palfner K, Hiddemann W, Kneba M. Elevated expression of S100P, CAPL and MAGE 3 in doxorubicin-resistant cell lines: comparison of mRNA differential display reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and subtractive suppressive hybridization for the analysis of differential gene expression. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9(4):311–7.

Wang L, Mao Y, Du G, He C, Han S. Overexpression of JARID1B is associated with poor prognosis and chemotherapy resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(4):2465–72.

Duan Z, Feller AJ, Toh HC, Makastorsis T, Seiden MV. TRAG-3, a novel gene, isolated from a taxol-resistant ovarian carcinoma cell line. Gene. 1999;229(1-2):75–81.

Wang QE, Han C, Milum K, Wani AA. Stem cell protein Piwil2 modulates chromatin modifications upon cisplatin treatment. Mutat Res. 2011;708(1-2):59–68.

Whitehurst AW, Xie Y, Purinton SC, Cappell KM, Swanik JT, Larson B, et al. Tumor antigen acrosin binding protein normalizes mitotic spindle function to promote cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(19):7652–61.

Odunsi K, Qian F, Matsuzaki J, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Andrews C, Hoffman EW, et al. Vaccination with an NY-ESO-1 peptide of HLA class I/II specificities induces integrated humoral and T cell responses in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(31):12837–42.

Odunsi K, Matsuzaki J, James SR, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Tsuji T, Miller A, et al. Epigenetic potentiation of NY-ESO-1 vaccine therapy in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(1):37–49.

Samlowski WE, Leachman SA, Wade M, Cassidy P, Porter-Gill P, Busby L, et al. Evaluation of a 7-day continuous intravenous infusion of decitabine: inhibition of promoter-specific and global genomic DNA methylation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(17):3897–905.

Schrump DS, Fischette MR, Nguyen DM, Zhao M, Li X, Kunst TF, et al. Phase I study of decitabine-mediated gene expression in patients with cancers involving the lungs, esophagus, or pleura. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(19):5777–85.

Cruz CR, Gerdemann U, Leen AM, Shafer JA, Ku S, Tzou B, et al. Improving T-cell therapy for relapsed EBV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma by targeting upregulated MAGE-A4. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(22):7058–66.

Esfandiary A, Ghafouri-Fard S. MAGE-A3: an immunogenic target used in clinical practice. Immunotherapy. 2015;7(6):683–704.

Chiriva-Internati M, Wang Z, Xue Y, Bumm K, Hahn AB, Lim SH. Sperm protein 17 (Sp17) in multiple myeloma: opportunity for myeloma-specific donor T cell infusion to enhance graft-versus-myeloma effect without increasing graft-versus-host disease risk. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(8):2277–83.

Chiriva-Internati M, Wang Z, Salati E, Timmins P, Lim SH. Tumor vaccine for ovarian carcinoma targeting sperm protein 17. Cancer. 2002;94(9):2447–53.

Chiriva-Internati M, Yu Y, Mirandola L, Jenkins MR, Chapman C, Cannon M, et al. Cancer testis antigen vaccination affords long-term protection in a murine model of ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10471.

Xiang SD, Gao Q, Wilson KL, Heyerick A, Plebanski M. A Nanoparticle Based Sp17 Peptide Vaccine Exposes New Immuno-Dominant and Species Cross-reactive B Cell Epitopes. Vaccines (Basel). 2015;3(4):875–93.

Renaud S, Loukinov D, Alberti L, Vostrov A, Kwon YW, Bosman FT, et al. BORIS/CTCFL-mediated transcriptional regulation of the hTERT telomerase gene in testicular and ovarian tumor cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(3):862–73.

Tureci O, Sahin U, Koslowski M, Buss B, Bell C, Ballweber P, et al. A novel tumour associated leucine zipper protein targeting to sites of gene transcription and splicing. Oncogene. 2002;21(24):3879–88.

Zhao J, Wang Y, Mu C, Xu Y, Sang J. MAGEA1 interacts with FBXW7 and regulates ubiquitin ligase-mediated turnover of NICD1 in breast and ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36(35):5023–34.

Fan R, Huang W, Luo B, Zhang QM, Xiao SW, Xie XX. Cancer testis antigen OY-TES-1: analysis of protein expression in ovarian cancer with tissue microarrays. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36(3):298–303.

Brenne K, Nymoen DA, Reich R, Davidson B. PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma) is a novel marker for differentiating serous carcinoma from malignant mesothelioma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(2):240–7.

Khan G, Brooks SE, Mills KI, Guinn BA. Infrequent Expression of the Cancer-Testis Antigen, PASD1, in Ovarian Cancer. Biomark Cancer. 2015;7:31–8.

Li S, Meng L, Zhu C, Wu L, Bai X, Wei J, et al. The universal overexpression of a cancer testis antigen hiwi is associated with cancer angiogenesis. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(4):1063–8.

Lu L, Katsaros D, Risch HA, Canuto EM, Biglia N, Yu H. MicroRNA let-7a modifies the effect of self-renewal gene HIWI on patient survival of epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55(4):357–65.

Lim SL, Ricciardelli C, Oehler MK, Tan IM, Russell D, Grutzner F. Overexpression of piRNA pathway genes in epithelial ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99687.

Tchabo NE, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Caballero OL, Villella J, Beck AF, Miliotto AJ, et al. Expression and serum immunoreactivity of developmentally restricted differentiation antigens in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Immun. 2009;9:6.

Wang X, Baddoo MC, Yin Q. The placental specific gene, PLAC1, is induced by the Epstein-Barr virus and is expressed in human tumor cells. Virol J. 2014;11:107.

Ha JH, Yan M, Gomathinayagam R, Jayaraman M, Husain S, Liu J, et al. Aberrant expression of JNK-associated leucine-zipper protein, JLP, promotes accelerated growth of ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(45):72845–59.

Straughn JM Jr, Shaw DR, Guerrero A, Bhoola SM, Racelis A, Wang Z, et al. Expression of sperm protein 17 (Sp17) in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(6):805–11.

Tureci O, Chen YT, Sahin U, Gure AO, Zwick C, Villena C, et al. Expression of SSX genes in human tumors. Int J Cancer. 1998;77(1):19–23.

Adair SJ, Carr TM, Fink MJ, Slingluff CL Jr, Hogan KT. The TAG family of cancer/testis antigens is widely expressed in a variety of malignancies and gives rise to HLA-A2-restricted epitopes. J Immunother. 2008;31(1):7–17.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all investigators at the participating study sites.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81702569, 81801413), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20170151), Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Development Foundation (JQX18009), Jiangsu Provincial Women and Children Health Research Project (F201762), Jiangsu Province “six talent peak” personal training project (2016-WSW-086, 2015-WSW-043) and Science and Technology Development Foundation Item of Nanjing Medical University (2016NJMUZD065).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KX and CF wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the table. SW, HX, SL, YS, ZG, XW, BX, JH, JX and PX provided advice regarding the paper. XJ, JW and KX critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, K., Fu, C., Wang, S. et al. Cancer-testis antigens in ovarian cancer: implication for biomarkers and therapeutic targets. J Ovarian Res 12, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0475-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0475-z