Abstract

Background

Additional treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (GnRHa) before IVF-ET (ultralong GnRHa therapy) has been reported to improve the outcome of IVF-ET in endometriosis patients. However, the mechanism of ultralong GnRHa therapy is unclear. It is suggested that inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress contribute to infertility in endometriosis patients. Therefore, in order to search a possible mechanism of ultralong GnRHa therapy, we investigated the effect of ultralong GnRHa therapy on intrafollicular concentrations of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), oxidative stress markers, and antioxidants in patients with endometriosis.

Methods

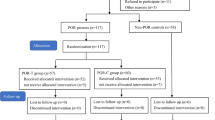

Twenty-three infertile women with Stage III or IV endometriosis were recruited for this study. Eleven patients received three courses of GnRHa (1.8 mg s.c. every 28 days), followed by a standard controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) for IVF-ET (ultralong group). The other 12 patients received a standard COH with mid-luteal phase GnRHa down-regulation (control group). The numbers of matured follicles and retrieved oocytes, fertilization rates, implantation rates, clinical pregnancy rate, and intrafollicular concentrations of TNFα, 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and hexanoyl-lysine adduct (HEL) as oxidative stress markers, and melatonin and Cu,Zu-superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD) as antioxidants were compared between the two groups.

Results

The numbers of mature follicles and retrieved oocytes, and fertilization rates did not differ between the two groups. Implantation rates and pregnancy rates tended to be higher in the ultralong group (21.4% and 27.3%, respectively) compared with the control group (8.3% and 8.3%, respectively). TNFα concentrations in the follicular fluid were significantly lower in the ultralong group (5.8 ± 3.2 pg/ml) than those in the control group (10.6 ± 3.2 pg/ml). Follicular concentrations of 8-OHdG concentrations were significantly lower in the ultralong group (5.7 ± 1.6 ng/ml) than those in the control group (6.6 ± 1.5 ng/ml), while melatonin concentrations were significantly higher in the ultralong group (139 ± 46 pg/ml) compared with the control group (86 ± 27 pg/ml).

Conclusions

Ultralong GnRHa therapy reduces the detrimental effects of cytotoxic cytokines and oxidative stress in the ovary in patients with endometriosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Endometriosis is considered to be the most intractable cause of female infertility [1],[2]. Possible causes of the infertility include poor quality of oocytes and embryos [3], impaired fertilization [4],[5], and impaired implantation [6], each of which can be induced by inflammation and oxidative stress in the pelvic cavity [7]-[9]. In fact, increased levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) have been observed in the peritoneal fluid in patients with endometriosis [10]. TNFα, which is produced by activated macrophages and NK cells, is a key molecule in endometriosis. TNFα in the peritoneal cavity impairs oocytes and embryos by its cytotoxicity [11],[12]. TNFα also increases prostaglandin production by endometrial epithelial cells, which in turn initiates a surge of other inflammatory cytokines in the endometrium [13],[14]. This surge of inflammatory cytokines has been proposed as a cause of endometriosis-related implantation failure [13],[14]. In addition, endometriosis patients showed high concentrations of TNFα in ovarian follicular fluids, which is associated with poor oocyte quality or impaired fertilization [11].

Chronic inflammation in the pelvic cavity of endometriosis patients also induces oxidative stress in both the pelvic cavity and reproductive organs. Increased and activated macrophages and polymorphonuclear leucocytes in the peritoneal fluid produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in patients with endometriosis [15]. Oxidative stress levels in the ovarian follicular fluid are higher in patients with endometriosis than in other infertility patients without endometriosis [16]. ROS production by endometrium is increased in endometriosis patients [17]. Oxidative stress causes detrimental effects on cells through lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage. Oxidative stress in the peritoneal cavity is one of the causes of endometriosis-associated infertility [8]. Oxidative stress reduces oocyte quality [18]-[20] and impairs endometrial receptivity [21]. Together, these findings strongly suggest that oxidative stress contributes to infertility in endometriosis patients.

The pregnancy outcomes of endometriosis patients who undergo in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) are generally poor [22], and there are no effective treatments for endometriosis-related infertility. Additional treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (GnRHa) before IVF-ET (ultralong GnRHa therapy) improved the outcome of IVF-ET in endometriosis patients, as shown by increased numbers of retrieved oocytes and transferred embryos, and higher implantation and pregnancy rates [23]-[25]. However, the mechanism of ultralong GnRHa therapy is unclear. Therefore, we investigated the concentrations of TNFα and oxidative stress in ovarian follicular fluids to see if they can shed light on the mechanism by which ultralong GnRHa therapy improves the IVF-ET outcome in endometriosis patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical study

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients in this study. Twenty-three infertile female patients with endometriosis were recruited for this study. The mean age ± S.D. of the patients was 34.0 ± 3.3 yr. with a range of 28–40 yr. Diagnosis of endometriosis was confirmed by laparoscopy, laparotomy, or transvaginal aspiration of the ovarian endometrial cyst. Severity of endometriosis was scored according to the four-stage classification of the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) score, and all patients had stage III or IV endometriosis. Patients were nonsmokers and free from major medical illness including hypertension; all were interested in becoming pregnant. Patients were excluded if they had myoma, adenomyosis, a congenital uterine anomaly, or if they used any kind of sex-steroidal agent including estrogens, progesterone, androgens, and OC.

Eleven patients received three courses of GnRHa (1.8 mg s.c. every 28 days) (buserelin acetate, Suprecur; Mochida Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), followed by a standard controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) for IVF-ET (ultralong group). Withdrawal bleeding was induced using estrogen (Premarin: conjugated estrogens tablets, Pfizer Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Japan) and progesterone (Duphaston: dydrogesterone tablets, Daiichi-Sankyo Co. Ltd., Japan) before COH. COH was initiated from the 2nd day of the IVF-ET cycle by injection of 225 IU FSH (Folyrmon P; Fuji Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for 3 days, followed by a daily injection of 150 IU HMG (HMG F; Fuji Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Nasal spray GnRHa (900 μg/day buserelin acetate, Suprecur; Mochida Pharmaceutical) was also given from the 2nd day of the IVF-ET cycle to continuously suppress pituitary gonadotropin secretion until the injection of HCG (HCG Mochida 10,000 IU; Mochida Pharmaceutical) for ovulation induction. Ultralong group included one case with a male factor.

Twelve patients received a standard COH with mid-luteal phase GnRHa down-regulation (control group). In the control group, nasal spray GnRHa (900 μg/day) was given from the mid-luteal phase in the previous cycle to the time of HCG injection for ovulation induction of the IVF-ET cycle. COH was given in a manner similar to the ultralong group described above.

When leading follicles reached 18 mm or more, HCG was injected for ovulation induction. Oocyte retrieval was carried out 35 h after HCG injection. Each mature follicle (more than 18 mm in diameter) was aspirated separately and the follicular fluid containing the oocyte was collected. Immediately after removal of the oocyte, each of the follicular fluids was centrifuged at 300 x g for 15 min to remove cellular components. The supernatant from each follicle was mixed in each patient and was kept at –80C until assayed. The numbers of matured follicles, retrieved oocytes and fertilized oocytes, and fertilization rates, implantation rates, and clinical pregnancy rates were compared between the two groups. Concentrations of TNFα, IL-6, and oxidative stress markers; 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a marker of DNA damage and hexanoyl-lysine adduct (HEL) as a marker of lipid peroxidation, and Cu,Zu-superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD) and melatonin, as antioxidants, in follicular fluids were measured using an ELISA kit or a radioimmunoassay described below.

Measurement of TNFα, IL-6, oxidative stress markers, and antioxidants in follicular fluids

Concentrations of TNFα and IL-6 were measured using a Human TNFα ELISA kit and Human IL-6 ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, USA), respectively. Each sample of follicular fluid (50 μl) was used for duplicate assay according to the assay protocol. The sensitivity of TNFα was 2 pg/ml, and the coefficients of variation (CV) for intra- and inter-assay were 4.5% and 5.2%, respectively. The sensitivity of IL-6 was 1 pg/ml, and the CV for intra- and inter-assay were <10%.

8-OHdG concentrations were measured using a New 8-OHdG Check ELISA (Japan Institute for the Control of Aging, Nikken SEIL Co. Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan) as we reported previously [26],[27]. Each sample of follicular fluid (50 μl) filtered using an ultrafilter (cut off molecular weight 10 kDa) was used for duplicate assay. The sensitivity of 8-OHdG was 0.5 ng/ml, and the CV for intra- and inter-assay were 5.5% and 6.1%, respectively.

HEL concentrations were measured using an ELISA kit (Japan Institute for the Control of Aging) as we reported previously [26],[27]. Each sample of follicular fluid (50 μl) was pretreated with chymotrypsin to perform proteolysis, and filtered using an ultrafilter (cut off molecular weight 10 kDa) for duplicate assay. The minimal detectable concentration of HEL was estimated to be 2 nmol/L.

Cu,Zn-SOD concentrations were measured using a Human Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase ELISA kit (Northwest Life Science Specialties, LLC, USA) as we reported previously [26],[27]. Each sample of follicular fluid (20 μl) was used for duplicate assay according to assay protocol. The sensitivity of Cu,Zn-SOD was 0.04 ng/ml, and the CV for intra- and inter-assay were 5.1% and 5.8%, respectively.

Intrafollicular concentrations of melatonin were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) as we reported previously [28]. Each sample of follicular fluid (500 μl) was used for duplicate assay. The sensitivity of the assay was 4.2 pg/ml, and the CV for intra- and inter-assay were 6.3% and 4.9%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS for Windows 13.0. The Mann–Whitney U-test using the Bonferroni correction and Fisher's test were employed as appropriate. Correlations were analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. Differences were considered to be significant if P <0.05.

Results

There was no significant difference in the mean age of the patients between the two groups (Table 1). These treatments resulted in the ultralong group receiving a greater dose of gonadotropin and a longer duration of ovarian stimulation (Table 1). The numbers of mature follicles and retrieved oocytes, and fertilization rates were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1). Embryo transfer was carried out in 8 of 12 cases in the control group and in 8 of 11 cases in the ultralong group (Table 1). The implantation rate and pregnancy rate were higher in the ultralong group (21.4% and 27.3%, respectively) compared with the control group (8.3% and 8.3%, respectively), but the differences were not significant (Table 1).

TNFα concentrations in the follicular fluid were significantly lower in the ultralong group (5.8 ± 3.2 pg/ml) than in the control group (10.6 ± 3.2 pg/ml) (Figure 1). IL-6 was not detected in the follicular fluid in either group. 8-OHdG concentrations were slightly but significantly lower in the ultralong group (5.7 ± 1.6 ng/ml) than in the control group (6.6 ± 1.5 ng/ml), whereas the follicular HEL concentrations were not significantly different (Figure 2). Melatonin concentrations were significantly higher in the ultralong group (139.2 ± 45.7 pg/ml) than in the control group (85.6 ± 27.4 pg/ml), while Cu,Zn-SOD concentrations were not significantly different between the two groups (Figure 3).

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) concentrations in follicular fluids. Twenty-three infertile women with Stage III or IV endometriosis were recruited for this study. Eleven patients received three courses of GnRHa (1.8 mg s.c. every 28 days), followed by a standard controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) for IVF-ET (ultralong group). Twelve patients received a standard COH with mid-luteal phase GnRHa down-regulation (control group). TNFα concentrations were measured in the follicular fluid obtained at the time of oocyte retrieval. Values are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was employed with the Mann–Whitney U-test using the Bonferroni correction.

Concentrations of oxidative stress markers in follicular fluids. Twenty-three infertile women with Stage III or IV endometriosis were recruited for this study. Eleven patients received three courses of GnRHa (1.8 mg s.c. every 28 days), followed by a standard controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) for IVF-ET (ultralong group). Twelve patients received a standard COH with mid-luteal phase GnRHa down-regulation (control group). The levels of oxidative stress markers; 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a marker of DNA damage and hexanoyl-lysine adduct (HEL) as a marker of lipid peroxidation, were measured in the follicular fluid obtained at the time of oocyte retrieval. Values are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was employed with the Mann–Whitney U-test using the Bonferroni correction.

Concentrations of antioxidants in follicular fluids. Twenty-three infertile women with Stage III or IV endometriosis were recruited for this study. Eleven patients received three courses of GnRHa (1.8 mg s.c. every 28 days), followed by a standard controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) for IVF-ET (ultralong group). Twelve patients received a standard COH with mid-luteal phase GnRHa down-regulation (control group). The levels of Cu,Zu-superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD) and melatonin, as antioxidants, were measured in the follicular fluid obtained at the time of oocyte retrieval. Values are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was employed with the Mann–Whitney U-test using the Bonferroni correction.

The correlations between TNFα, 8-OHdG and melatonin concentrations in the follicle were analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. There were slight positive correlations between TNFα and 8-OHdG (R = 0.1178, P = 0.5924), and negative correlations between TNFα and melatonin (R = –0.0893, P = 0.6852) and melatonin and 8-OHdG (R = –0.3976, P = 0.0602). However, the trends were not statistically significant because of a small sample size.

Discussion

The present result clearly showed that the concentrations of a cytotoxic cytokine (TNFα) and oxidative stress (8-OHdG) in follicular fluids were significantly lower in the ultralong GnRHa therapy group than in the control group, suggesting a potential mechanism that additional GnRHa treatment before IVF-ET improves the pregnancy outcome of IVF-ET by reducing the detrimental effects of cytotoxic cytokines and oxidative stress in the peritoneal environment or implantation environment in patients with endometriosis. TNFα and oxidative stress in ovarian follicles not only damage oocytes and embryos leading to the impaired fertilization, but also impair endometrial receptivity leading to implantation failure in patients with endometriosis [10]-[14].

Although ultralong GnRHa therapy reduced the concentrations of TNFα and oxidative stress markers in ovarian follicles, it is unclear whether it also reduced them in the peritoneal cavity and in the endometrium. Since it is reported that the cytokine levels were decreased by GnRHa treatment in the peritoneal cavity as well as in the ovary [29],[30], there is a possibility that the hostile environment of the peritoneal cavity and endometrial cavity was improved by ultralong GnRHa therapy in this study. Therefore, we hypothesize that the decrease in TNFα and oxidative stress by ultralong GnRHa therapy may have contributed to the improvement of implantation rate and pregnancy rate.

Interestingly, ultralong GnRHa therapy increased the melatonin concentrations in the follicular fluid (Figure 3). Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland, and regulates a variety of central and peripheral actions related to circadian rhythms and reproduction. Melatonin is a powerful free radical scavenger and a broad-spectrum antioxidant [31],[32]. We previously demonstrated that melatonin is present in human ovarian follicles and that its concentration increases during follicular growth [18]-[20]. We also reported that melatonin is taken up into the follicular fluid from the blood, and that it protects oocytes from ROS within the follicle during ovulation [18]-[20],[33]. Reduced oxidative stress and increased antioxidant activities by melatonin in follicular fluids by ultralong GnRHa therapy may also have contributed to the improvement of implantation rate and pregnancy rate. The mechanism by which ultralong GnRHa therapy increases the melatonin concentration in the follicle is unclear. We speculate that ultralong GnRHa therapy may have improved the function of the follicle by reducing inflammation of the ovary so that the follicle can effectively take up melatonin.

It is unclear how TNFα, oxidative stress, and melatonin interacts each other. There were slight positive correlations between TNFα and 8-OHdG, and negative correlations between TNFα and melatonin, and melatonin and 8-OHdG, although the trends were not statistically significant. These results may suggest that TNFα induces oxidative stress and decreases melatonin levels in the follicle. In other words, the reduced TNFα by ultralong GnRHa therapy may be responsible for the decrease in oxidative stress and the increase in melatonin in the follicle.

On the other hand, as a demerit of the ultralong GnRHa therapy, our results showed a need for greater gonadotropin doses and longer COH days than in patients who received a standard mid-luteal GnRHa down-regulation protocol, which is also consistent with previous reports [34].

Unfortunately, the present study did not clearly show that ultralong GnRHa therapy improves the fertility of patients with endometriosis. This may be due to the small sample size of this study. A large-scale randomized controlled trial will be necessary to evaluate the efficacy of ultralong GnRHa therapy on pregnancy outcome in patients with endometriosis. It is also interesting to investigate whether there are any differences in follicular levels of TNFα, 8-OHdG, and melatonin between the follicles containing fertilized and unfertilized, implanted and non-implanted, or pregnant and non-pregnant oocytes.

Conclusions

This study suggested a possible mechanism of ultralong GnRHa therapy to improve the pregnancy outcome of IVF-ET, which is the reduction of the detrimental effect of cytokines and oxidative stress in the peritoneal environment or implantation environment in patients with endometriosis.

Authors' contributions

HT and AT designed the study and wrote the manuscript. AT, YN and FN collected and analysed the data. NS coordinated and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

Akande VA, Hunt LP, Cahill DJ, Jenkins JM: Differences in time to natural conception between women with unexplained infertility and infertile women with minor endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2004, 19: 96–103. 10.1093/humrep/deh045

Collins JA, Burrows EA, Wilan AR: The prognosis for live birth among untreated infertile couples. Fertil Steril 1995, 64: 22–28.

Brizek CL, Schlaff S, Pellegrini VA, Frank JB, Worrilow KC: Increased incidence of aberrant morphological phenotypes in human embryogenesis–an association with endometriosis. J Assist Reprod Genet 1995, 12: 106–112. 10.1007/BF02211378

Azem F, Lessing JB, Geva E, Shahar A, Lerner-Geva L, Yovel I, Amit A: Patients with stages III and IV endometriosis have a poorer outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer than patients with tubal infertility. Fertil Steril 1999, 72: 1107–1109. 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00392-1

Simon C, Gutierrez A, Vidal A, Santos MJ D l, Tarin JJ, Remohi J, Pellicer A: Outcome of patients with endometriosis in assisted reproduction: results from in-vitro fertilization and oocyte donation. Hum Reprod 1994, 9: 725–729.

Garrido N, Navarro J, Garcia-Velasco J, Remoh J, Pellice A, Simon C: The endometrium versus embryonic quality in endometriosis-related infertility. Hum Reprod Update 2002, 8: 95–103. 10.1093/humupd/8.1.95

Augoulea A, Mastorakos G, Lambrinoudaki I, Christodoulakos G, Creatsas G: The role of the oxidative-stress in the endometriosis-related infertility. Gynecol Endocrinol 2009, 25: 75–81. 10.1080/09513590802485012

Gupta S, Agarwal A, Krajcir N, Alvarez JG: Role of oxidative stress in endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online 2006, 13: 126–134. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62026-3

Jackson LW, Schisterman EF, Dey-Rao R, Browne R, Armstrong D: Oxidative stress and endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005, 20: 2014–2020. 10.1093/humrep/dei001

Harada T, Yoshioka H, Yoshida S, Iwabe T, Onohara Y, Tanikawa M, Terakawa N: Increased interleukin-6 levels in peritoneal fluid of infertile patients with active endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997, 176: 593–597. 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70553-2

Falconer H, Sundqvist J, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Von Schoultz B, D'Hooghe TM, Fried G: IVF outcome in women with endometriosis in relation to tumour necrosis factor and anti-Mullerian hormone. Reprod Biomed Online 2009, 18: 582–588. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60138-1

Lee KS, Joo BS, Na YJ, Yoon MS, Choi OH, Kim WW: Relationships between concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and nitric oxide in follicular fluid and oocyte quality. J Assist Reprod Genet 2000, 17: 222–228. 10.1023/A:1009495913119

Iwabe T, Harada T, Tsudo T, Nagano Y, Yoshida S, Tanikawa M, Terakawa N: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells by inducing interleukin-8 gene and protein expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85: 824–829.

Yamauchi N, Harada T, Taniguchi F, Yoshida S, Iwabe T, Terakawa N: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced the release of interleukin-6 from endometriotic stromal cells by the nuclear factor-kappaB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Fertil Steril 2004,82(Suppl 3):1023–1028. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.02.134

Zeller JM, Henig I, Radwanska E, Dmowski WP: Enhancement of human monocyte and peritoneal macrophage chemiluminescence activities in women with endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol 1987, 13: 78–82.

Seino T, Saito H, Kaneko T, Takahashi T, Kawachiya S, Kurachi H: Eight-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine in granulosa cells is correlated with the quality of oocytes and embryos in an in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer program. Fertil Steril 2002, 77: 1184–1190. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03103-5

Ngo C, Chereau C, Nicco C, Weill B, Chapron C, Batteux F: Reactive oxygen species controls endometriosis progression. Am J Pathol 2009, 175: 225–234. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080804

Tamura H, Nakamura Y, Korkmaz A, Manchester LC, Tan DX, Sugino N, Reiter RJ: Melatonin and the ovary: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Fertil Steril 2009, 92: 328–343. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.016

Tamura H, Takasaki A, Taketani T, Tanabe M, Kizuka F, Lee L, Tamura I, Maekawa R, Aasada H, Yamagata Y, Sugino N: The role of melatonin as an antioxidant in the follicle. J Ovarian Res 2012, 5: 5. 10.1186/1757-2215-5-5

Tamura H, Takasaki A, Taketani T, Tanabe M, Kizuka F, Lee L, Tamura I, Maekawa R, Asada H, Yamagata Y, Sugino N: Melatonin as a free radical scavenger in the ovarian follicle. Endocr J 2013, 60: 1–13. 10.1507/endocrj.EJ12-0263

Sugino N: The role of oxygen radical-mediated signaling pathways in endometrial function. Placenta 2007,28(Suppl A):S133–136. 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.12.002

Barnhart K, Dunsmoor-Su R, Coutifaris C: Effect of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 2002, 77: 1148–1155. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03112-6

Surrey ES, Silverberg KM, Surrey MW, Schoolcraft WB: Effect of prolonged gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy on the outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2002, 78: 699–704. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03373-3

24. Sallam HN, Garcia-Velasco JA, Dias S, Arici A: Long-term pituitary down-regulation before in vitro fertilization (IVF) for women with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD004635

Rickes D, Nickel I, Kropf S, Kleinstein J: Increased pregnancy rates after ultralong postoperative therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2002, 78: 757–762. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03338-1

Taketani T, Tamura H, Takasaki A, Lee L, Kizuka F, Tamura I, Taniguchi K, Maekawa R, Asada H, Shimamura K, Reiter RJ, Sugino N: Protective role of melatonin in progesterone production by human luteal cells. J Pineal Res 2011, 51: 207–213. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00878.x

Tamura H, Nakamura Y, Takiguchi S, Kashida S, Yamagata Y, Sugino N, Kato H: Melatonin directly suppresses steroid production by preovulatory follicles in the cyclic hamster. J Pineal Res 1998, 25: 135–141. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1998.tb00551.x

Tamura H, Nakamura Y, Takiguchi S, Kashida S, Yamagata Y, Sugino N, Kato H: Pinealectomy of melatonin implantation does not affect prolactin surge or luteal function in pseudopregnant rats. Endocr J 1998, 45: 377–383. 10.1507/endocrj.45.377

Iwabe T, Harada T, Sakamoto Y, Iba Y, Horie S, Mitsunari M, Terakawa N: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment reduced serum interleukin-6 concentrations in patients with ovarian endometriomas. Fertil Steril 2003, 80: 300–304. 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00609-5

Kupker W, Schultze-Mosgau A, Diedrich K: Paracrine changes in the peritoneal environment of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 1998, 4: 719–723. 10.1093/humupd/4.5.719

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Fuentes-Broto L: Melatonin: a multitasking molecule. Prog Brain Res 2010, 181: 127–151. 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)81008-4

Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, Flores LJ, Reiter RJ: One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res 2007, 42: 28–42. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x

Tamura H, Takasaki A, Miwa I, Taniguchi K, Maekawa R, Asada H, Taketani T, Matsuoka A, Yamagata Y, Shimamura K, Morioka H, Ishikawa H, Reiter RJ, Sugino N: Oxidative stress impairs oocyte quality and melatonin protects oocytes from free radical damage and improves fertilization rate. J Pineal Res 2008, 44: 280–287. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00524.x

Cota AM, Oliveira JB, Petersen CG, Mauri AL, Massaro FC, Silva LF, Nicoletti A, Cavagna M, Baruffi RL, Franco JG Jr: GnRH agonist versus GnRH antagonist in assisted reproduction cycles: oocyte morphology. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012, 10: 33–40. 10.1186/1477-7827-10-33

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

NS has received financial support for research from Mochida Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, which is not directly related with this study.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tamura, H., Takasaki, A., Nakamura, Y. et al. A pilot study to search possible mechanisms of ultralong gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy in IVF-ET patients with endometriosis. J Ovarian Res 7, 100 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-014-0100-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-014-0100-8