Abstract

Background

The prevalence of foot osteoarthritis (OA) is much less understood than hip, knee and hand OA. The foot is anatomically complex and different researchers have investigated different joints with lack of methodological standardisation across studies. The La Trobe Foot Atlas (LFA) is the first to address these issues in providing quantitative assessment of radiographic foot OA, but has not been tested externally. The aim of this study was to evaluate three different interpretive approaches to using the LFA for grading OA when scoring is difficult due to indistinct views of interosseous space and joint contour.

Methods

Foot radiographs of all remaining participants (n = 218) assessed in the Chingford Women Study 23 year visit (mean (SD) for age: 75.5 years (5.1)) were scored using the LFA defined protocol (Technique 1). Two revised scoring strategies were applied to the radiographs in addition to the standard LFA analyses. Technique 2 categorised joints that were difficult to grade as ‘missing’. Technique 3 included joints that were difficult to grade as an over estimated score. Radiographic OA prevalence was defined for the foot both collectively and separately for individual joints.

Results

When radiographs were scored using the LFA (Technique 1), radiographic foot OA was present in 89.9%. For Technique 2 the presence of radiographic foot OA was 83.5% and for Technique 3 it was 97.2%. At the individual joint level, using Technique 1, the presence of radiographic foot OA was higher with a wider range (18.3–74.3%) than Technique 2 (17.9–46.3%) and lower with a wider range (18.3–74.3%) than Technique 3 (39.9–79.4%).

Conclusion

The three different ways of interpreting the LFA scoring system when grading of individual joints is technically difficult and result in very different estimates of foot OA prevalence at both the individual joint and global foot level. Agreement on the best strategy is required to improve comparability between studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is an important cause of global disability, with adult prevalence rates reported between 8.5–22.0% for symptomatic radiographic knee OA [1,2,3], 3.4–8.9% for symptomatic radiographic hip OA [2, 4, 5]. The prevalence of radiographic hand OA has been reported to range from 27.0 to 83.0% [2, 6]. Hand OA is said to consist of several phenotypes that make it more complex to study [7]. Whilst investigation of foot joints may be more aligned to those of the hand as a peripheral joint site with multiple small bones and joints, the prevalence of radiographic foot OA is much less understood.

Foot pain is often linked to foot OA and is highly prevalent in the general population, with estimates that range between 15.0–63.0% [8,9,10,11]. Although conventional radiographs have been used traditionally to assess OA there is discordance in how radiographic and symptomatic OA are defined [12,13,14] and a lack of methodological standardisation across studies [9]. For investigations of foot OA, issues such as the considerable variation in study populations, the radiographic views taken, which foot joints are examined, the grading systems applied and definitions for prevalence of radiographic foot OA are highlighted as potential reasons for the lack of conclusive data regarding radiographic and symptomatic foot OA [15]. Of these factors the lack of standardisation in the methods used to assess radiographic foot OA [15], the number of foot joints included to define foot OA [16] and the disparity between radiographic OA and symptomatic OA [17, 18] appear to be key issues to address. Recently, the UK population prevalence of symptomatic radiographic foot OA has been estimated as 16.7% in adults aged over 50 years [19] and in the US prevalence estimates of pain at specific foot locations range between 7 and 13% in adults (30–100 years) [20].

Experts agree that the separate grading of osteophytes (OPs) and joint space narrowing (JSN) using standardised and validated atlases is an important way forward [21, 22]. In an attempt to address this, Menz et al. [23] developed a radiographic atlas specifically for standardising the documentation and interpretation of foot OA. The atlas uses an ordinal scale to score the presence of OP and JSN at five joints within the foot on dorsoplantar and lateral views [23]. Previously investigators largely relied on the Kellgren and Lawrence classification system [24] to define OA in individual foot joints, which was often limited just to the first metatarsophalangeal joint (1stMTPJ) [12, 15, 25].

Menz et al. reported good intra-rater reliability (percentage agreement from 86.0 to 99.0% and weighted κ from 0.45 to 0.95), of the La Trobe Foot Atlas (LFA) and construct validity relative to foot symptoms [16, 23]. The LFA has since been used to determine the prevalence of radiographic OA at the global foot level in relation to foot pain [19] and effects of intervention at an individual joint level [26]. Studies using the LFA that did not include a member of the original team that developed the atlas are scarce [25] or do not discuss the use of the atlas [27] such that the interpretation of the LFA scoring has yet to be evaluated.

The presentation of radiographic features varies quite widely. As radiographic atlases use semi-quantitative or ordinal grading systems to classify individuals, often into 4 or 5 categories, a degree of interpretation is required in order to categorise OA features [28,29,30,31]. We postulated that, as with other radiographic atlases, the LFA ordinal technique for scoring introduces an interpretative approach, that may potentially lead to an over or under-estimation in the prevalence of OA [31]. This is particularly likely when an unclear view of a joint is being assessed, which happens often for views of the midfoot and certain hind-foot joints [16, 23, 32]. The authors of the original LFA themselves do suggest from their inter-rater reliability results that “there is some degree of inherent variability in the interpretation of some aspects of the atlas” [23]. We wished to evaluate how much this variation in interpretation can affect the prevalence of radiographic foot OA.

Methods

Study participants

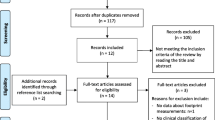

Foot radiographs were sourced from a well-established population-based cohort of middle aged women - ‘The Chingford 1000 Women Study’ (http://www.chingfordstudy.org.uk) (see Fig. 1 recruitment flow chart). This prospective cohort originally comprised 1003 women aged 45–64 years from a general practice in Chingford, North-East London, UK. Participants have been followed annually since 1989 and are representative of women in the UK general population with respect to weight, height, and smoking characteristics, the details of which have been previously published [33,34,35,36]. The ‘Chingford 1000 Women Study’ has focussed on the natural history of OA and osteoporosis and has followed strict well-established protocols.

Full ethical approval was granted by Waltham Forest and Redbridge Local Research Ethics Committee (reference number: LREC R & WF 96). The study was sponsored by Whipps Cross Hospital Research and Development Unit. An amendment application was approved for the year 23 clinical foot assessment study by NRES Committee South Central – Oxford A (May 2013; REC number: 84,131). All participants gave fully informed written consent.

Foot radiographs

A sample of foot radiographs taken at year 23 (collected between 2013 and 2014), were used to evaluate prevalence of radiographic foot OA between different scoring techniques. The sample included all women who returned for the 23 year visit and had foot radiographs taken (n = 218) with mean (SD) age: 75.5 years (5.1); weight: 69.2 kg (12.6); height: 158.4 cm (6.1); BMI: 27.6 (4.8). The participants at the year 23 visit were therefore older with a higher BMI than at the baseline year 0 visit, mean (SD) age: 54.1 (6.4) and BMI: 25.3 (4.3). There was no significant difference in age or BMI between those who attended for foot x-ray and those who did not at year 23.

All radiographs at this time point were taken weight bearing in two views (dorsoplantar and lateral) of each foot according to the LFA defined protocol [23, 37] and stored on disc.

Radiographic scoring of foot osteoarthritis

The LFA focuses on 5 of the 32 joints of each foot, specifically: the 1st MTPJ; the first cuneiform-metatarsal joint (1stCMJ); the second cuneiform-metatarsal joint (2ndCMJ); the navicular-first cuneiform joint (N1stCJ); and the talo-navicular joint (TNJ). A four-point scale of 0, 1, 2 and 3 is used to score OPs (0 = absent; 1 = small; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe) and JSN (0 = none; 1 = definite; 2 = severe; 3 = bone-on-bone at least one point) in both feet in both the dorsoplantar and lateral view. Although the scale description proposed in the LFA publication [23] describes JSN grade 3 as “joint fusion” we have interpreted this more precisely as “bone-on-bone”. Foot OA is considered to be present if a score of 2 or more is documented for either OP or JSN on either of the two views [23].

Pictorial guidance for each grade of OP and JSN is provided for each view. The exception is the TNJ for OP grading on the dorsoplantar view, which was excluded from the LFA as the authors asserted that OP more commonly develops on the dorsal aspect of this joint which is difficult to visualize from a dorsoplantar projection [23]. Joints that could not be scored (e.g. Due to surgical removal or presence of other pathology) were excluded from the analyses.

All radiographs were scored by a single trained reader (PMc).

Scoring techniques

Two revised scoring methods were applied to the foot radiographs in addition to the standard LFA analyses to determine prevalence of radiographic foot OA between different interpretive approaches:

-

Technique 1 was employed as the LFA standard technique [23] whereby all joints that were difficult to interpret and score for OPs and/or JSN were given a score based on a conservative estimate. (For example, where an OP in a participant’s joint may have been ambiguous to score between a grading of 2 or 3, the lower grading of ‘2’ was accepted).

-

Technique 2 was a new approach not used previously. It was devised by our team of experts in the field of osteoarthritis (NKA, MD), radiography (MM) and foot and ankle research (CB) to understand how the prevalence estimate of foot OA changed when a scorer did not include an estimate for any joint they could not make a decision on.

All joints that were difficult to interpret and score for OPs and/or JSN were designated as missing values and excluded from the analyses (under-estimate).

-

Technique 3 was a revised version of Technique 1 whereby all joints that were difficult to interpret and score for OPs and/or JSN were given a score based on an over-estimate. (For example, where an OP in a participant’s joint may have been ambiguous to score between a grading of 2 or 3, the higher grading of ‘3’ was accepted).

Scorer reliability

The reader (PMc) had undergone training by an experienced radiographer (MM) who had used the LFA in a previous OA foot study [19, 37]. Using a sample (n = 20) of archived radiographs of both feet (Chingford year 6) and the LFA standard technique (Technique 1), for dorsoplantar views, intra-rater agreement was established for each LFA category at the individual joint level by overall percentage agreement and weighted kappa statistics (for categorical scoring) of OPs and JSN) based on value criteria by Landis and Koch [38]. For the five joints and both feet the range was fair to substantial for OPs and poor to substantial for JSN; percentage close agreement ranged from 47.6–85.7% for OPs and from 33.3–81.0% for JSN (Table 1).

Statistics

Data evaluation and statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). The distribution of data was initially examined using histograms and scatter plots. No ‘outliers’ were found that may have occurred due to data entry bias or normal biological outliers. Assessment of the different radiographic scoring techniques are described using frequency (%) of radiographic foot OA at person foot level and individual joint level. Differences between the techniques are reported as frequency range.

Results

When the foot radiographs (Chingford year 23) were scored using the LFA (Technique 1), the total (i.e. combined joints of left and right feet) prevalence of radiographic foot OA in any joint in the right and left foot was 81.2% using only the dorsoplantar view and 83.5% using only the lateral view. When scores were combined for both views and both feet radiographic foot OA was present in 89.9% of participants (Table 2). For Technique 2 (categorising joints that were difficult to grade as ‘missing’) the prevalence of radiographic foot OA was 83.5% (both feet, both views). For Technique 3 (attributing an over estimated score to joints that were difficult to grade) the prevalence of radiographic foot OA was 97.2% (Table 3).

At the individual joint level, Technique 2 elicited a lower presence of radiographic foot OA than Technique 1 (Table 2). With the exception of the 2nd CMJ (both feet and both views) that elicited a difference of 36.2% (both feet) between Techniques 1 and 2 joint scores, all other joint scores were within an acceptable range (left foot: 1.4–4.6%; right foot: 0.4–6.3%). Conversely, at the individual joint level Technique 3 elicited a higher presence of radiographic foot OA than Technique 1. With the exception of the N1stCJ (both feet, dorsoplantar view) that elicited a difference of 49.1% (left foot) and 52.3% (right foot) between Technique 1 and 3 scores, all other joint scores were within a less wide range (left foot: 5.1–19.3%; right foot: 4.2–21.6%).

At the individual joint level, using Technique 1, the presence of radiographic foot OA for combined OP and JSN was higher with a wider range (18.3–74.3%) than Technique 2 (17.9–46.3%). At the individual joint level, using Technique 1, the presence of radiographic foot OA for combined OP and JSN was lower with a wider range (18.3–74.3%) than Technique 3 (39.9–79.4%).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to extend knowledge of radiographic foot OA by examining three different interpretive approaches to classifying foot OA using the LFA. The three different ways of interpreting the LFA scoring system when scoring individual joints that we used is technically difficult and each resulted in different estimates of foot OA prevalence at both the individual joint and global foot level.

Similar to other radiographic scoring methods, such as Kellgren and Lawrence [24, 39] and the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) atlas [40], there is potential ambiguity in the interpretation of the scoring for OPs and JSN within individual joints using the LFA. Scoring of foot joints on radiographs presents specific problems due to overlap of bones that makes it difficult to clearly see the joint line and OP on any one view in all joints of interest. Through comparison of the different techniques we showed the potential for the range of prevalence estimates of person level radiographic foot OA to be between 83.5% and 97.2%.

Menz et al. [16] reported the prevalence of radiographic foot OA in their elderly sample (as 93%, which is similar to our standard LFA assessment of 89.9% and within our range when utilising the two additional techniques. Menz et al. [16] also reported a joint-specific prevalence rate for individual joints that ranged between 23.0–60.0% which is similar to the range between 18.3–74.3% that we found. The sample size that Menz et al. [16] investigated and age was similar to ours (n = 197, mean age 75.9 years, [SD] 6.6), however they were drawn from a retirement village and a university health sciences clinic in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia with 64.0% women, whilst ours were all women drawn from a general population in the UK.

Other investigators have reported lower prevalence estimates for foot OA. For example, in an American population, the Clearwater Osteoarthritis Study, a prospective cohort consisting of 3463 participants (40–94 years), Wilder et al. [41] reported a prevalence of 20.0% of radiographic foot OA. Within that study, the focus was on one only foot joint only, the 1st MTPJ, so a lower prevalence of OA at the individual foot joint level is expected. Our findings were higher 35.8% (left) and 42.2% (right) for presence of OA in the 1st MTPJ. The lower estimate produced by Wilder et al. [41] may be due to the fact that their scoring was based on the traditional Kellgren and Lawrence scale which is not as sensitive to radiographic foot OA as the LFA [16].

It is not just the approach that is open to interpretation. Even using the different techniques, our estimates are much higher, than the most recent UK study that estimated the population prevalence of symptomatic radiographic foot OA as 16.7% [19]. The latter study used foot pain and foot OA (ie symptoms plus radiographs) to define their prevalence of symptomatic foot OA, whereas we only used foot OA (radiographs). This highlights the marked difference in prevalence estimates dependent on whether the focus of investigation is on symptomatic radiographic foot OA or just radiographic foot OA, the latter being distinctly much higher [2]. The difference in prevalence estimates due to the case definition has been noted in OA at other joints sites [2].

Each of these examples may go some way to explaining the variation in published prevalence estimates of radiographic foot OA, especially when different techniques are employed and different joints included. Other factors that may explain the differences in prevalence estimates of radiographic foot OA could be related to the subjectivity of the scoring method being ordinal as opposed to objective measurements such as joint space width. As a further example, we found that scoring may be confounded as the individual features of OP or JSN are not presented separately but are mixed and this may distract the scorer to judge the “best-fit” picture due to the overall appearance rather than to just the OP or JSN they are scoring.

The advice given in the LFA indicates that use of both dorsoplantar and lateral views is ‘gold standard’ and should be applied where possible to ensure an appropriate level of sensitivity to OA [23]. Further evaluation of the LFA has shown that good sensitivity (94.6%) can be obtained in the 1st MTPJ when only a dorsoplantar view is available. However, substantially lower sensitivity was achieved for the other joints (between 31.0 and 60.7% of cases) [16]. The 1st MTPJ is the largest of the MTPJs and is not obscured by other joints when observed in radiographs and as such easier to assess the presence of OPs and JSN. Menz et al. [16] reported the combined view was 42.4% for the 1stMTPJ which is very similar to our estimate of combined view 1st MTPJ presence of OA as 35.8% for the left foot (dorsoplantar view: 27.1%; lateral view: 22.9%) and 42.2% for the right foot (dorsoplantar view: 33.0%; lateral view: 27.5%). Of note, the joints that showed most difference between our techniques were the 2nd CMJ and N1stCJ. These joints are also the ones noted to be difficult to score in the LFA atlas due to considerable amount of overlap of bones and joints [23].

There are limitations to this study. Firstly, it is possible that our estimates of prevalence may have been confounded by the lower reproducibility of the rater in this study than that of the original authors of the LFA [23]. There are a number of explanations for lower reliability scores in our preliminary work such as the foot positioning for the reliability study differed from that undertaken by the LFA, availability of only one view (non-weight-bearing dorso-plantar) and lower quality of foot radiographs versus higher quality of resolution of electronic images used in year 23. For the development and testing of the LFA, the same authors selected the radiographs for each LFA classification grade on which their reliability was calculated [23]. This may provide more stable predictions of reliability scores but may not be as readily applicable to new raters external to the original development team.

Secondly, the cohort used in the development of the LFA was a sample of the Australian population over the age of 65 years, whereas the foot radiographs used in this study were all from a sample of women of the UK population aged 69–93 years. There is currently no available foot radiographic data that compares different populations that may have different physiology, anatomy and genetics. Consequently, we do not know how representative the pictures used to explain the scoring method within the LFA are for global comparisons or how closely the Chingford 1000 Women’s study cohort foot radiographs may align to them. Of note, within the LFA there are not separate pictures for OPs or JSN for men and women. It is currently not known if factors such as joint width are smaller in foot joints of women than men which may affect interpretation and scoring for OA.

Thirdly, differences in prevalence estimates of foot OA could be related to study populations and the focus of the investigation. The focus of our investigation was radiographic features of foot OA only. We have not aligned this to symptoms of foot pain as our aim was to evaluate the scoring technique for foot OA using a validated radiographic atlas. Our findings are therefore not directly comparable with other investigators reporting on the prevalence of symptomatic foot OA. Whilst symptomatic foot OA may be more prevalent in women [19] we are aware that the prevalence of foot OA was very high in our study. We believe this could be due to a combination of the population being all women aged over 69 years in whom OA has generally been found to be more prevalent [42]. Additionally, in our study, OA was defined radiographically which has been shown to lead to higher estimates than other definitions such as ‘self-reported OA’ and ‘symptomatic OA’ (combined radiographic OA with symptoms) [2]. Estimates of the prevalence of OA of a similar order have been reported at other peripheral joints sites in other populations of older women [43].

Conclusion

This study supports the use of the La Trobe Foot Atlas to facilitate standardised scoring of foot OA in existing current and historical radiographs of established large population cohorts with the caveat that the interpretative scoring technique requires acknowledgment. We have evaluated three different ways of interpreting the scoring system when scoring of individual joints is technically difficult and results in different estimates of foot OA prevalence at both the individual joint and global foot level. This strengthens the case for further refinement of definitions for foot OA between investigators and improved comparability between studies. Future work should focus on agreement on the best strategy to improve comparability between studies to begin to identify the risk factors for foot OA. From that the field can move forward in developing best clinical strategies for prevention and management of foot OA.

Abbreviations

- LFA:

-

The La Trobe Foot Atlas

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

References

Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, Fang F, Schwartz TA, Abbate LM, Callahan LF, et al. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County osteoarthritis project. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:172–80.

Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araujo J, Branco J, Santos RA, Ramos E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2011;19:1270–85.

Turkiewicz A. Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Engstrom G, Nilsson PM, Mellstrom C, Lohmander LS, Englund M: prevalence of knee pain and knee OA in southern Sweden and the proportion that seeks medical care. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2015;54:827–35.

Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, Fang F, Schwartz TA, Nelson AE, Abbate LM, et al. Prevalence of hip symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County osteoarthritis project. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:809–15.

Kim C, Linsenmeyer KD, Vlad SC, Guermazi A, Clancy MM, Niu J, Felson DT. Prevalence of radiographic and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in an urban United States community: the Framingham osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:3013–7.

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35.

Zhang W, Doherty M, Leeb BF, Alekseeva L, Arden NK, Bijlsma JW, Dincer F, Dziedzic K, Hauselmann HJ, Kaklamanis P, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis: report of a task force of ESCISIT. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:8–17.

Hill CL, Gill TK, Menz HB, Taylor AW. Prevalence and correlates of foot pain in a population-based study: the north West Adelaide health study. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1:1–7.

Thomas MJ, Roddy E, Zhang W, Menz HB, Hannan MT, Peat GM. The population prevalence of foot and ankle pain in middle and old age: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152:2870–80.

Gill TK, Menz HB, Landorf KB, Arnold JB, Taylor AW, Hill CL. Predictors of foot pain in the community: the north West Adelaide health study. J Foot Ankle Res. 2016;9:1–8.

Garrow AP, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. The Cheshire foot pain and disability survey: a population survey assessing prevalence and associations. Pain. 2004;110:378–84.

Iagnocco A, Rizzo C, Gattamelata A, Vavala C, Ceccarelli F, Cravotto E, Valesini G. Osteoarthritis of the foot: a review of the current state of knowledge. Med Ultrason. 2013;15:35–40.

Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116.

Peat G, Croft P, Hay E. Clinical assessment of the osteoarthritis patient. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:527–44.

Trivedi B, Marshall M, Belcher J, Roddy E. A systematic review of radiographic definitions of foot osteoarthritis in population-based studies. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:1027–35.

Menz HB, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB, Zammit GV, Cicuttini FM. Radiographic evaluation of foot osteoarthritis: sensitivity of radiographic variables and relationship to symptoms. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17:298–303.

Hannan MT, Felson DT, Pincus T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1513–7.

Hart DJ, Spector TD, Brown P, Wilson P, Doyle DV, Silman AJ. Clinical signs of early osteoarthritis: reproducibility and relation to x ray changes in 541 women in the general population. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:467–70.

Roddy E, Thomas MJ, Marshall M, Rathod T, Myers H, Menz HB, Thomas E, Peat G. The population prevalence of symptomatic radiographic foot osteoarthritis in community-dwelling older adults: cross-sectional findings from the clinical assessment study of the foot. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:156–63.

Dufour AB, Broe KE, Nguyen US, Gagnon DR, Hillstrom HJ, Walker AH, Kivell E, Hannan MT. Foot pain: is current or past shoewear a factor? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1352–8.

Hart DJ, Spector TD. The classification and assessment of osteoarthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1995;9:407–32.

Spector TD, Hart DJ, Byrne J, Harris PA, Dacre JE, Doyle DV. Definition of osteoarthritis of the knee for epidemiological studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:790–4.

Menz HB, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB, Zammit GV, Cicuttini FM. Radiographic classification of osteoarthritis in commonly affected joints of the foot. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15:1333–8.

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502.

Kalichman L, Hernandez-Molina G. Midfoot and forefoot osteoarthritis. Foot (Edinb). 2014;24:128–34.

Munteanu SE, Zammit GV, Menz HB, Landorf KB, Handley CJ, Elzarka A, Deluca J. Effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronan (Synvisc, hylan G-F 20) for the treatment of first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1838–41.

Halstead J, Chapman GJ, Gray JC, Grainger AJ, Brown S, Wilkins RA, Roddy E, Helliwell PS, Keenan AM, Redmond AC. Foot orthoses in the treatment of symptomatic midfoot osteoarthritis using clinical and biomechanical outcomes: a randomised feasibility study. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:987–96.

Gossec L, Jordan JM, Lam MA, Fang F, Renner JB, Davis A, Hawker GA, Dougados M, Maillefert JF. OA O-Otftaraomi: comparative evaluation of three semi-quantitative radiographic grading techniques for hip osteoarthritis in terms of validity and reproducibility in 1404 radiographs: report of the OARSI-OMERACT task force. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17:182–7.

Croft P. An introduction to the atlas of standard radiographs of arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2005;44(Suppl 4):iv42.

Hart DJ, Spector TD. Radiographic criteria for epidemiologic studies of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1995;43:46–8.

Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1886–93.

Wilder FV, Barrett JP Jr, Farina EJ. Effect of regular exercise on the radiographic progression of foot osteoarthritis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95:342–6.

Hart D, Spector T, Egger P, Coggon D, Cooper C. Defining osteoarthritis of the hand for epidemiological studies: the Chingford study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:220–3.

Hart DJ, Doyle DV, Spector TD. Incidence and risk factors for radiographic knee osteoarthritis in middle-aged women: the Chingford study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:17–24.

Hart DJ, Mootoosamy I, Doyle DV, Spector TD. The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis in the general population: the Chingford study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:158–62.

Hart DJ, Spector TD. The relationship of obesity, fat distribution and osteoarthritis in women in the general population: the Chingford study. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:331–5.

Roddy E, Myers H, Thomas MJ, Marshall M, D'Cruz D, Menz HB, Belcher J, Muller S, Peat G. The clinical assessment study of the foot (CASF): study protocol for a prospective observational study of foot pain and foot osteoarthritis in the general population. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4:22.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Kellgren JH. The epidemiology of chronic rheumatism; Volume II. Atlas of Standard Radiographs of Arthritis. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1963.

Altman RD, Gold GE. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(Suppl A):A1–56.

Wilder FV, Barrett JP, Farina EJ. The association of radiographic foot osteoarthritis and radiographic osteoarthritis at other sites. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2005;13:211–5.

van Saase JL, van Romunde LK, Cats A, Vandenbroucke JP, Valkenburg HA. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: Zoetermeer survey. Comparison of radiological osteoarthritis in a Dutch population with that in 10 other populations. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:271–80.

Yoshida S, Aoyagi K, Felson DT, Aliabadi P, Shindo H, Takemoto T. Comparison of the prevalence of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee and hand between Japan and the United States. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1454–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants of the Chingford Women Study, Professor Tim Spector, Dr. Deborah Hart, Dr. Alan Hakim, Maxine Daniels and Alison Turner for their time and dedication and the Oxford NIHR Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit for funding contributions.

Funding

The Chingford Women’s Study is supported by a project grant from Arthritis Research UK and the year 23 ft project was supported by a project grant from the Dr. W.M Scholl podiatric research and development fund. CB is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Institute for Health Research. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research, NHS or the Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The data from this study informs part of a larger programme of work study. Data related to the Chingford 1000 Women’s study are available from the ‘Access Committee’ upon reasonable request. A completed analysis plan for consideration by the committee review panel should be emailed to: Alison.Turner@ndorms.ox.ac.uk

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PM, CB, NA, LG, MM and MD conceived and designed the study. CB and PM acquired all x-rays, PM completed x ray scoring, PM, CB, LG, MM, NA, MD helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Full ethical approval was granted by Waltham Forest and Redbridge local research ethic committee (reference number: LREC R & WF 96); the study was sponsored by Whipps Cross Hospital Research and Development Unit. Approval for the year 25 clinical foot assessment study was granted by NRES Committee South Central – Oxford A which was received in May 2013 (REC number: 84,131).

Consent for publication

All participants gave informed consent.

Competing interests

Prof Catherine Bowen is the Deputy Editor of the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. It is journal policy that editors are removed from the peer review and editorial decision-making processes for papers they have co-authored. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this work. There were no benefits received nor will there be from commercial or business based organisations either directly or indirectly relating to this article to any persons involved in this research.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

McQueen, P., Gates, L., Marshall, M. et al. The effect of variation in interpretation of the La Trobe radiographic foot atlas on the prevalence of foot osteoarthritis in older women: the Chingford general population cohort. J Foot Ankle Res 10, 54 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-017-0239-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-017-0239-9