Abstract

Background

FBLN5-related cutis laxa (CL) is a rare disorder that involves elastic fiber-enriched tissues and is characterized by lax skin and variable systemic involvement such as pulmonary emphysema, arterial involvement, inguinal hernias, hollow viscus diverticula and pyloric stenosis. This type of CL follows mostly autosomal recessive (AR) and less commonly autosomal dominant patterns of inheritance.

Results

In this study, we detected a novel homozygous missense variant in exon 6 of FBLN5 gene (c.G544C, p.A182P) by using whole exome sequencing in a consanguineous Iranian family with two affected members. Our twin patients showed some of the clinical manifestation of FBLN5-related CL but they did not present pulmonary complications, gastrointestinal and genitourinary abnormalities. The notable thing about this monozygotic twin sisters is that only one of them showed ventricular septal defect, suggesting that this type of CL has intrafamilial variability. Co-segregation analysis showed the patients’ parents and relatives were heterozygous for detected variation suggesting AR form of the CL. In silico prediction tools showed that this mutation is pathogenic and 3D modeling of the normal and mutant protein revealed relative structural alteration of fibulin-5 suggesting that the A182P can contribute to the CL phenotype via the combined effect of lack of protein function and partly misfolding-associated toxicity.

Conclusion

We underlined the probable roles and functions of the involved domain of fibulin-5 and proposed some possible mechanisms involved in AR form of FBLN5-related CL. However, further functional studies and subsequent clinical and molecular investigations are needed to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cutis laxa (CL) as a hereditary disorder of skin and connective tissue which can display autosomal dominant (ADCL), autosomal recessive (ARCL), and X-linked recessive (XRCL) inheritance, and also can be acquired [1,2,3]. The inherited form of CL presents in the early months of life while acquired forms are associated with a late onset presentation, generally in adulthood. This disorder is highly heterogeneous and characterized by loose, redundant, wrinkled and hypoelastic skin as a result of errors in elastic fibers synthesis and structural deficiencies of proteins involved in the extracellular matrix [3, 4]. Since the disease is a connective tissue disorder, its features are associated with multisystem involvement but the precise patho-mechanism of this variable systemic involvement has not been clearly illustrated [5,6,7]. The prevalence of CL has not been estimated precisely, but the inherited forms of the disease have an incidence of approximately 1 to 2: 400,000 [4].

The ADCL is caused by mutations in structural genes coding for elastin (ELN), fibulin-5 (FBLN5) and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 18 Family Member A1 (ALDH18A1), and shows ranges of benign clinical variability [8, 9]. Patients are mostly diagnosed in early childhood with loose skin and some systemic involvements (gastrointestinal diverticula, hernias, cardiac and pulmonary complications such as emphysema and bronchiectasis). The manifestations can range from mild to severe but the patients generally have a normal life span in spite of experiencing serious systemic problems like aortic aneurysm [2, 8, 10] (Table 1).

The ARCL is the most common and variable form of CL which is subsequently divided into nine subtypes based on genetic and clinical characterizations. There are various ARCL-associated genes such as the FBLN5, EGF containing fibulin extracellular matrix protein 2 (EFEMP2 also known as FBLN4), latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 4 (LTBP4), ATPase H + transporting V0 subunit a2 (ATP6V0A2), pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 (PYCR1), ATPase H + transporting V1 subunit E1 (ATP6V1E1), ATPase H + transporting V1 subunit A (ATP6V1A), aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family member A1 (ALDH18A1) and PYCR1. This type of CL is often a life threatening, generalized neonatal disorder with severe systemic manifestation such as severe gastrointestinal, cardiopulmonary, and urinary abnormalities alongside with the skin manifestations which are presented in the whole body [2, 4, 11] (Table 2).

Patients with XRCL also known as Occipital horn syndrome show distinct phenotypic features at birth such as hyperextensible wrinkled skin with droopy faces, occipital horns, neurologic defects, urinary tract infections, bladder diverticulae, orthostatic hypotension, inguinal hernias and diarrhea [12, 13]. This form of CL is caused by mutation in ATPase copper transporting alpha (ATP7A) gene which is involved in copper secretion from nonhepatic tissues, copper absorption from the small intestine, and copper transport across the blood–brain barrier [5, 13, 14] (Table 1).

Here, we present a family with ARCL type-IA in their members as a result of a novel mutation in the FBLN5 gene. We also propose some explanations for phenotype heterogeneity and suggest some possible mechanisms of CL pathogenesis resulting from different mutations in the FBLN5 gene.

Material and methods

Patients

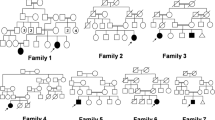

Two-year-old monozygotic twin sisters whose parents were consanguineous and had experienced about a 10-year infertility, were referred to GMG center for genetic analysis (Fig. 1). These twins have been conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF). When they were 7 months, old wrinkled, loose and sagging skin appeared on their whole body specifically on groins, necks, armpits and faces. Additionally, physical examination indicated excessive growth of facial and body hair, sparse eyebrows, big eyes, dysplastic ears and premature aging appearance (Fig. 2). Extra investigations for systemic involvements did not reveal any pulmonary complications, gastrointestinal and genitourinary abnormalities, but one of them was diagnosed with ventricular septal defect (VSD). The study protocol was approved by Ethical Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed written consent forms were obtained from study participants.

The patients’ parents and relatives were phenotypically normal and did not have symptoms of connective tissue disorders or multiple congenital anomalies in their children with the exception of the probands' cousin who had albinism.

Molecular genetic studies

We got written informed consent from the parents and their relatives for genetic analysis and publication of the patients’ photos. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Genomic DNA of patients and their family members was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes using DNA extraction kit (GeneAll Exgene Blood SV Mini). Initially, whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed in one of twin sisters to identify genetic bases of CL in this family. Once the variant has been detected, specific primers including 5′-AGAAGAATCCTGGGCAGTGG-3′ as forward primer and 5′-CGCATAGCAAGGTTCAGGTC-3′ as reverse primer were designed for subsequent co-segregation analysis of the other sister and family members.

Results

Molecular genetics results

Clinical diagnosis of affected individuals was on the basis of characteristic features, and they were suspected with different forms of CL at initial clinical evaluation. To diagnose a specific type of CL and identify inheritance pattern of the disease, the proband was analyzed through WES. A novel homozygous missense variant in exon 6 of FBLN5 gene (c.G544C, p.A182P, reference sequence: NM_006329.3) was detected, suggesting the diagnosis of FBLN5-associated CL form. The variant is classified as "likely pathogenic" according to the ACMG guidelines (PM1, PM2, PP1, PP3) [15]. The nucleotide 544 in exon 6 and its corresponding amino acid Alanine is evolutionarily conserved across species from Homo sapience to Callorhinus ursinus (Fig. 3). This variant has not been reported in previous studies and gene variant public databases such as gnomAD, ClinVar, dbSNP, NCBI, EXOME variant databases, 1000 genome and HGMD. Based on most predictors including Mutation Taster, Ensembl variant effect predictor, and HANSA, this variant is pathogenic with SIFT and PolyPhen scores of 0.01 and 0.99, respectively. Protein structure predictors have shown that with substitution of Alanine with Proline in 182 position of FBLN5, the 3D structure of the protein has not changed significantly (Fig. 4).

FBLN5-associated CL shows both autosomal dominant and recessive patterns of inheritance [16, 17]. Since none of consanguineous parents and also their relatives showed sign and symptoms of CL according to the pedigree, autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance was strongly suggested. To rule out any possibility of autosomal dominant inheritance especially in case of de novo mutation, co-segregation analysis of the variants was done. Our analysis showed that both parents and their mothers were heterozygous for this variation, stating the autosomal recessive mode of inheritance (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The inherited form of CL can be caused by variations in diverse genes, which disrupt elastogenesis. In this study we assessed the clinical signs of monozygotic twin sisters and identified a novel homozygous missense variant in exon 6 of FBLN5 gene through molecular analysis. Although the phenotype of FBLN5-related CL is broad, our patients did not show any pulmonary complications, gastrointestinal and genitourinary abnormalities. An interesting point about our patients is that only one of them showed VSD, suggesting that this type of CL has intrafamilial variability. Fibulin-5 is one of the integrin-binding members of the class II fibulin subfamily that is mostly found in the elastic-fibre-rich tissues such as skin, aorta, lung, and uterus [18, 19]. This glycoprotein is 66-kDa in size, contains 448 amino acids, including a signal sequence of 23 amino acids at the N-terminal, six calcium-binding EGF (cbEGF)-like motifs, and a C-terminal globular domain of 134 residues. An unusual long linker sequence with about 28 amino acids is present between the 4th and 5th cysteine residues of the first cbEGF motif. This domain also encompasses an RGD (arginine-glycine-asparatic acid) sequence that is evolutionally conserved [17, 20, 21].

The RGD motif is found in several matricellular and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such asosteopontin, fibronectin, thrombospondins, and vitronectin, and participates in cellular functions by binding with a subset of cell surface heteromeric integrins [20, 22]. The RGD sequence is the binding motif of fibulin-5 to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [23]. This motif and the flanking domains in the N-terminal half of fibulin-5 act as mediators of cell attachment through interactions with αvβ3, αvβ5 and α9β1 integrin. Furthermore, the N-terminal half of fibulin-5 mediates attachment and spreading of primary aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) via binding to α5β1 and α4β1 fibronectin receptors but not to αvβ3 [24, 25]. However, after unmasking the RGD motif by reduction and alkylation in a direct protein interaction study, it has been shown that fibulin-5 could bind to αvβ3 [26]. Also, truncated protein with only the first cbEGF domain was not able to bind and spread SMCs, suggesting that other domains of fibulin-5 in the middle and C-terminus may be involved in this process. It is interesting that fibulin-5 after binding to α5β1 and α4β1 integrins is not able to activate downstream signaling. This protein has been proposed to be an inhibitor for fibronectin receptor-mediated signaling in a dominant-negative manner because of its dose-dependent antagonized role for fibronectin-induced stress fiber formation and focal adhesions in SMCs [20]. Considering the significance of the RGD domain in the assembly of elastic fibers, generating a D56E variation which known as a disrupting factor of the ECM to RGD-dependent integrins binding, showed completely normal elastic fibers assembly, suggesting that it is not necessary for formation of elastic fibers cell-surface binding of fibulin-5 [20, 26].

The cbEGF domains are found in most trans-membrane and ECM proteins and facilitate protein–protein interactions [27]. Through these domains, fibulin-5 binds to multiple ECM proteins including tropoelastin, latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP)-2, lysyl oxidase like 1 (Loxl-1), Loxl-2, and 4, which are critical for elastic fiber assembly [28, 29]. For elastogenesis, a series of highly regulated steps including secretion and aggregation of the tropoelastin which is called coactivation, appropriate assembly and cross-linking of the tropoelastin, and then insoluble elastin organization into functional fibers are essential [30]. Fibulin-5 via binding to tropoelastin accelerates coacervation and also limits the maturation of elastin fragments which were coacervated [31, 32]. Another study has shown that in the skin of Fibulin5-null mice, the typical size of elastin aggregates was increased in comparison with wild-type mice [33]. According to these data, in the formation and maturation steps of coacervation process, fibulin-5 plays an important role in efficient control of coacervation and regulation of elastin aggregation optimal size for achieving accurate assembly and cross-linking of tropoealstin [20].

The identified novel homozygous missense variant in the current study leads to substitution of alanine 182 to proline in the third cbEGF. As mentioned above, the cbEGF motifs have critical role in elastic fiber assembly and variation of these domains can result in elastic fiber defects [34, 35]. Up to now, three different mutations namely I169T, R173H and G202R have been reported in the third cbEGF domain. The I169T variation decreases the secretion of the protein which compromises elastic fibre formation. The G202R that had been initially reported as a CL-related mutation was also detected in control groups in other study suggesting that this variant might not be pathogenic [35, 36]. The R173H variation has been detected in a Turkish family with affected child but the pathogenicity of the variant is obscure [16]. Other mutations in the adjacent domains such as V126M, C217R and S227P have been designated as pathogenic. The V126M not only causes hyperelasticity of the skin but also is associated with other diseases such as age-related macular degeneration and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1 [37]. Solid-phase binding and immunostaining studies in RFL-6 cells and patient-derived skin fibroblasts have shown that C217R and S227P are associated with reduction of fibulin-5-tropoelastin interaction. The second mutation was detected in two ethnically different families and results in a severe form of CL with internal organ involvement [38]. Considering the importance of the cbEGF motifs, it is obvious that pathogenic mutations in these motifs interfere with the fibulin-5 secretion and its matrix deposition which subsequently leads to diminished elastin polymerization. Considering that all the available variants predictors showed pathogenicity of A182P, we propose that this mutation may cause CL through disrupting of fibulin-5–tropoelastin interaction. Based on our 3D structure models both for wild and mutant fibulin-5 it seems that the A182P can contribute to the CL phenotype via the combined effect of lack of protein function and partly misfolding-associated toxicity. However, in a broader context, functional study of this variation is essential to uncover its pathogenicity and function of the cbEGF-3 domain.

Approximately all reported mutations of FBLN5, similar to the detected variation in this study follow autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, and only one alteration, a tandem duplication of cbEGF 2–5 motifs, has showed autosomal dominant inheritance in a patient with mild form of CL [17]. Since point mutations such as S227P result in endoplasmic reticulum stress related to the recruitment of folding chaperones and increase patient-derived cells apoptosis, it appears that the recessive CL mechanisms are not only associated with a loss of fibulin-5 functional but also involve decreased cell survival [38]. Considering this, the large mutant protein can act in a dominant negative fashion and in case of homozygosity might result in severe form of CL.

Conclusion

To sum up, we described clinical features of FBLN5-related CL and identified a novel variation in the cbEGF-3 domain. We also underlined the probable role and function of cbEGF motifs and proposed some possible mechanisms for recessive form of FBLN5-related CL. However, further functional studies are needed to confirm the pathogenicity of the variation and additional clinical and molecular investigations are indispensable to provide firm genotype–phenotype correlation and identify exact mechanisms which are involved in different types of this disorder.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CL:

-

Cutis laxa

- AR:

-

Autosomal recessive

- VSD:

-

Ventricular septal defect

- ADCL:

-

Autosomal dominant

- ARCL:

-

Autosomal recessive

- XRCL:

-

X-linked recessive

- ALDH18A1:

-

Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 18 Family Member A1

- ELN:

-

Elastin

- FBLN5:

-

Fibulin-5

- ATP7A:

-

ATPase copper transporting alpha

- IVF:

-

Vitro fertilization

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

- SMCs:

-

Aortic smooth muscle cells

- LTBP:

-

Latent TGF-β binding protein

References

Gara S, Litaiem N. Cutis Laxa (Elastolysis). StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2019.

Mohamed M, Kouwenberg D, Gardeitchik T, Kornak U, Wevers RA, Morava E. Metabolic cutis laxa syndromes. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34(4):907–16.

Mohamed M, Voet M, Gardeitchik T, Morava E. Cutis laxa Progress in heritable soft connective tissue diseases. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 161–84.

Morava E, Guillard M, Lefeber DJ, Wevers RA. Autosomal recessive cutis laxa syndrome revisited. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(9):1099–110.

Lin DS, Yeung CY, Liu HL, Ho CS, Shu CH, Chuang CK, et al. A novel mutation in PYCR1 causes an autosomal recessive cutis laxa with premature aging features in a family. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155(6):1285–9.

Kantaputra PN, Kaewgahya M, Wiwatwongwana A, Wiwatwongwana D, Sittiwangkul R, Iamaroon A, et al. Cutis laxa with pulmonary emphysema, conjunctivochalasis, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, abnormal hair, and a novel FBLN5 mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164(9):2370–7.

Gardeitchik T, Mohamed M, Fischer B, Lammens M, Lefeber D, Lace B, et al. Clinical and biochemical features guiding the diagnostics in neurometabolic cutis laxa. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(7):888–95.

Berk DR, Bentley DD, Bayliss SJ, Lind A, Urban Z. Cutis laxa: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(5):842-e1-842-e17.

Callewaert B, Renard M, Hucthagowder V, Albrecht B, Hausser I, Blair E, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of autosomal-dominant cutis laxa with report of five ELN mutations. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(4):445–55.

Graul-Neumann LM, Hausser I, Essayie M, Rauch A, Kraus C. Highly variable cutis laxa resulting from a dominant splicing mutation of the elastin gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146(8):977–83.

Elahi E, Kalhor R, Banihosseini SS, Torabi N, Pour-Jafari H, Houshmand M, et al. Homozygous missense mutation in fibulin-5 in an Iranian autosomal recessive cutis laxa pedigree and associated haplotype. J Investig Dermatol. 2006;126(7):1506–9.

Dagenais SL, Adam AN, Innis JW, Glover TW. A novel frameshift mutation in exon 23 of ATP7A (MNK) results in occipital horn syndrome and not in Menkes disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(2):420–7.

Tümer Z, Møller LB. Menkes disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(5):511–8.

Herman T, McAlister W, Boniface A, Whyte M. Occipital horn syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22(5):363–5.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–24.

Tekedereli I, Demiral E, Gokce IK, Esener Z, Camtosun E, Akinci A. Autosomal recessive cutis laxa: a novel mutation in the FBLN5 gene in a family. Clin Dysmorphol. 2019;28(2):63–5.

Markova D, Zou Y, Ringpfeil F, Sasaki T, Kostka G, Timpl R, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of cutis laxa: a heterozygous tandem duplication within the fibulin-5 (FBLN5) gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(4):998–1004.

Tsuda T. Extracellular interactions between fibulins and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β in physiological and pathological conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9):2787.

Kowal RC, Richardson JA, Miano JM, Olson EN. EVEC, a novel epidermal growth factor-like repeat-containing protein upregulated in embryonic and diseased adult vasculature. Circ Res. 1999;84(10):1166–76.

Yanagisawa H, Schluterman MK, Brekken RA. Fibulin-5, an integrin-binding matricellular protein: its function in development and disease. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3(3–4):337–47.

Argraves WS, Greene LM, Cooley MA, Gallagher WM. Fibulins: physiological and disease perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(12):1127–31.

Davis GE, Bayless KJ, Davis MJ, Meininger GA. Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(5):1489–98.

Nakamura T, Ruiz-Lozano P, Lindner V, Yabe D, Taniwaki M, Furukawa Y, et al. DANCE, a novel secreted RGD protein expressed in developing, atherosclerotic, and balloon-injured arteries. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(32):22476–83.

Nakamura T, Lozano PR, Ikeda Y, Iwanaga Y, Hinek A, Minamisawa S, et al. Fibulin-5/DANCE is essential for elastogenesis in vivo. Nature. 2002;415(6868):171–5.

Lomas AC, Mellody KT, Freeman LJ, Bax DV, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Fibulin-5 binds human smooth-muscle cells through α5β1 and α4β1 integrins, but does not support receptor activation. Biochem J. 2007;405(3):417–28.

Kobayashi N, Kostka G, Garbe JH, Keene DR, Bächinger HP, Hanisch F-G, et al. A comparative analysis of the fibulin protein family biochemical characterization, binding interactions, and tissue localization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):11805–16.

Maurer P, Hohenester E. Structural and functional aspects of calcium binding in extracellular matrix proteins. Matrix Biol. 1997;15(8–9):569–80.

Jones RP, Wang M-C, Jowitt TA, Ridley C, Mellody KT, Howard M, et al. Fibulin 5 forms a compact dimer in physiological solutions. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(38):25938–43.

Hirai M, Horiguchi M, Ohbayashi T, Kita T, Chien KR, Nakamura T. Latent TGF-β-binding protein 2 binds to DANCE/fibulin-5 and regulates elastic fiber assembly. EMBO J. 2007;26(14):3283–95.

Kelleher CM, McLean SE, Mecham RP. Vascular extracellular matrix and aortic development. Current topics in developmental biology, vol. 62. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. p. 153–88.

Wachi H, Nonaka R, Sato F, Shibata-Sato K, Ishida M, Iketani S, et al. Characterization of the molecular interaction between tropoelastin and DANCE/fibulin-5. J Biochem. 2008;143(5):633–9.

Cirulis JT, Bellingham CM, Davis EC, Hubmacher D, Reinhardt DP, Mecham RP, et al. Fibrillins, fibulins, and matrix-associated glycoprotein modulate the kinetics and morphology of in vitro self-assembly of a recombinant elastin-like polypeptide. Biochemistry. 2008;47(47):12601–13.

Choi J, Bergdahl A, Zheng Q, Starcher B, Yanagisawa H, Davis EC. Analysis of dermal elastic fibers in the absence of fibulin-5 reveals potential roles for fibulin-5 in elastic fiber assembly. Matrix Biol. 2009;28(4):211–20.

Claus S, Fischer J, Mégarbané H, Mégarbané A, Jobard F, Debret R, et al. A p. C217R mutation in fibulin-5 from cutis laxa patients is associated with incomplete extracellular matrix formation in a skin equivalent model. J Investig Dermatol. 2008;128(6):1442–50.

Jones RP, Ridley C, Jowitt TA, Wang M-C, Howard M, Bobola N, et al. Structural effects of fibulin 5 missense mutations associated with age-related macular degeneration and cutis laxa. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2356–62.

Lotery AJ, Baas D, Ridley C, Jones RP, Klaver CC, Stone E, et al. Reduced secretion of fibulin 5 in age-related macular degeneration and cutis laxa. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(6):568–74.

Auer-Grumbach M, Weger M, Fink-Puches R, Papić L, Fröhlich E, Auer-Grumbach P, et al. Fibulin-5 mutations link inherited neuropathies, age-related macular degeneration and hyperelastic skin. Brain. 2011;134(6):1839–52.

Hu Q, Loeys BL, Coucke PJ, De Paepe A, Mecham RP, Choi J, et al. Fibulin-5 mutations: mechanisms of impaired elastic fiber formation in recessive cutis laxa. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(23):3379–86.

Acknowledgements

The current study was supported by a grant from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT and SGF wrote the draft and revised it. JG and MR performed the experiment. AH and YJM analyzed the data. JAH and AHJR collected the data and supervised the study. All authors contributed equally and fully aware of submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participant

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent forms were obtained from all study participants. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1399.525). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent of publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gharesouran, J., Hosseinzadeh, H., Ghafouri-Fard, S. et al. New insight into clinical heterogeneity and inheritance diversity of FBLN5-related cutis laxa. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01696-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01696-6