Abstract

Background

The appropriate treatment in mild slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) should not only prevent further slipping of the epiphysis but also address potential femoroacetabular impingement by restoring the anatomy of the proximal femur. The aim of this study was to quantify length of the remodeling phase mediated by growth of the femoral neck, after treatment of SCFE with a screw designed to prevent premature closure of the physis and provide stability.

Methods

Between 2001 and 2011, 38 patients with unilateral mild SCFE were treated by fixation in situ using a modified screw which does not cause premature physeal arrest. Twenty-four patients were investigated for clinical and radiological evidence of femoroacetabular impingement immediately after surgery, at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Statistical analysis was performed comparing measurements of neck length and the α angle of the affected and contralateral side.

Results

Mean α angle immediately after pinning was 56.2 ± 10.6° on the anteroposterior view and 91.4 ± 8.2° on the lateral view. These measurements significantly improved at 6 months post-op to 48.9 ± 5.4° on the anteroposterior view and 51.2 ± 6.5° on the lateral view (p < 0.0001). At 12 months from surgery, AP view α angle was 43.0 ± 2.8° (p < 0.0001) and lateral view was 44.2 ± 4.1° (p < 0.0001). We observed a similar growth rate and speed of the femoral neck of both the affected and unaffected sides during the first year of treatment. The clinical results in all patients were rated as excellent.

Conclusion

Our data supports the use of a surgical technique that allows residual growth of the femoral neck following mild SCFE and permits restoration of the anatomy of the proximal femur while avoiding development of femoroacetabular impingement following mild SCFE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a possible cause of femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) and subsequent premature osteoarthritis of the hip [1,2,3]. Surgical treatment of SCFE depends on the severity of the slip. For mild slips, with angulation < 30°, fixation of the epiphysis in situ by smooth pins or screws is recommended [4,5,6,7]. Ward et al. (1992) [8] found that the more central the fixation, the earlier the physeodesis, especially using trans-physeal screw stabilization. Two studies suggest that after slippage of the epiphysis, changes occur at the acetabular labrum and adjacent cartilage which act as precursors of osteoarthritis of the affected hip joint [9, 10].

These two studies, which also analyzed moderate and severe SCFE, demonstrated articular erosions and scars and/or tears of the labrum, with damage to the articular cartilage ranging from superficial abrasions to full-thickness loss caused by a prominent femoral metaphysis protruding beyond or at least level with the physis.

Due to such findings, these studies recommended an osteochondroplasty at the femoral head-neck junction in addition to stabilization of the epiphysis in situ, in an attempt to reduce risk of developing secondary osteoarthritis [11].

As described by Menelaus (1991) [12], the femoral neck grows at an estimated rate of 4.0 mm/year. In younger patients, premature closure of the physis risks development of a short femoral neck, producing a short lever arm and a high-riding trochanter with progressive deformity of the epiphyseal–metaphyseal complex of the proximal femur, leading to premature osteoarthritis [13, 14]. A standard screw fixation associated with an osteochondroplasty may then cause a premature closure of the physis and consequent deformity of the head-neck junction associated with an overgrowth of the great trochanter. This might lead to intra- and extra-articular impingements [14], making the additional osteochondroplasty useless.

Our hypothesis is then to avoid an osteochondroplasty trusting in a biological remodeling due to growth. To reach this target, an ideal method in SCFE should stabilize the epiphysis without causing unwanted premature closure of the physis. Histologic, ultrastructural, and clinical studies post stabilization reported remodeling with normalization of the physis [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Remodeling due to the growth of the neck can reduce or eliminate head/neck incongruities.

Guzzanti et al. (2004) [19] reported the results obtained with a modified screw to stabilize the slip in younger patients with SCFE. This method avoided leg-length discrepancy and maintained articular trochanteric distance and growth of the epiphyseal–metaphyseal complex. Since some authors [11] recommended osteochondroplasty in addition to traditional in situ fixation to avoid the progression of the labrum and articular lesions, we decided to review the results provided by our method.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the remodeling speed of the deformity in all the patients with monolateral mild SCFE treated by in situ fixation using Guzzanti’s modified screw [19].

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù in Rome, Italy. Informed consent was obtained from all patients examined. Clinical and radiological records of all patients treated for a SCFE between 2001 and 2011 were reviewed.

Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Patients with unilateral stable or unstable SCFE with posterior slippage < 35°. We accepted 5° greater than 30° to account for the possibility of error when measuring. (2) Surgical treatment using in situ fixation with a modified cannulated screw [19]. (3) Complete clinical and radiological records for review from presentation to at least 1-year follow-up. Data was collected immediately post-surgery, at 6 months and at 1 year.

Exclusion criteria included hip trauma during the follow-up period, associated metabolic or endocrine disease, involvement of the contralateral hip during follow-up, and/or incomplete medical and imaging records. Medical charts and radiographs were reviewed to determine age at presentation, sex, laterality, postoperative complications, and outpatient follow-ups.

Operative technique

Surgery was carried out under fluoroscopic control. Spontaneous reduction occurred in the unstable slips when positioning the patient. A modified cannulated screw 90–120-mm long was used. The modified AO cannulated screw (HIT-MEDICA, Rimini, Italy) had a distal segment, with the original six threads reduced to three and were 9-mm long and 6.4 mm in diameter. The screw was inserted over a guide wire after pre-drilling. The threaded portion of the screw was placed entirely within the epiphysis with the smooth shank crossing the physis, femoral neck, and lateral femoral cortex. The screw head was allowed to remain about 1.5–2 cm to the side of the lateral femoral cortex (always under the iliotibial band to avoid disturbance to the patients) to provide for neck growth. This distance was based on the predicted growth of the proximal femur, plus a few additional millimeters, to facilitate removal using a guide wire if necessary. The position of the screw in the central quadrant of the femoral epiphysis was confirmed by multiple fluoroscopic views. The screw tip was positioned more than 2.5 mm from the epiphyseal subchondral bone. After insertion of the screw, the hip was taken through a full range of movement with multiple fluoroscopic views to check the final hardware position. Post-operation, patients with a stable SCFE were allowed to weight-bear as tolerated. Those with an unstable SCFE used crutches with partial weight-bearing for 4 weeks.

Pre-operative assessment included clinical and radiological classification of the SCFE in terms of severity and type (stable/unstable). The pre- and post-operative head-neck slip angles were measured on anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs (with the leg held in a device at 90° of flexion and 45° of abduction. This is a modified abduction of the 90° Dunn view position [22]) taken at a standard 100-cm beam distance [23]. Any change of 5° or more was considered significant. A negative value was considered a decrease and a positive value an increase in slip angle. Radiographic measurements were made digitally using the CARESTREAM DRX-Evolution system. Slip severity was measured on pre-operative lateral radiographs with the posterior sloping angle (PSA) [23].

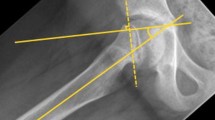

PSA is the angle between the plane of the physis and the line perpendicular to the femoral neck axis. To assess cam deformity, two measurements were performed: alpha (α) angle in AP and lateral view radiographs in the affected and unaffected hips (Fig. 1).

SCFE of the left hip in an 11.2-year-old boy. a, b AP view radiograms: a post-operative α angle and b α angle at 12 months FU. c, d Lateral view radiograms: c post-operative α angle and d α angle at 12 months FU: observe the normalization of the angle and the absence of head/neck deformity (case 23 in Tables 1 and 2)

Measurements were performed immediately after pinning, at 6 months and at 12 months post-operatively. The α angle was measured on AP and lateral view radiograms following the methodology of Clohisy et al. (2008) [22]. It is calculated by measuring the angle between two lines: (1) a line drawn connecting the center of the femoral head to the point on the anterolateral and lateral view aspect of the head-neck junction, where the radius of the femoral head is found in the acetabulum (i.e., where a prominence starts), and (2) a line drawn through the center of the femoral neck, connecting to the center of the femoral head. An α angle greater than 50° is suggestive of cam deformity [24]. Concurrently, neck length was measured on a line drawn from the lateral femoral cortex to the physis on the AP view, as shown in Fig. 2.

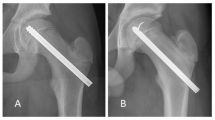

SCFE of the right hip in a 13.7-year-old boy. a, b AP view radiograms: a post-operative and b at 12 months FU: neck length (O-L) was measured from the lateral femoral cortex drawing a line perpendicular to the physis plane; the neck grew in the same way on the affected and unaffected sides, as growth of the femoral neck progressed, the screw advanced into the femoral neck from the lateral femoral cortex closing the gap between the lateral femoral cortex and the screw head. c, d Lateral view radiograms: c post-operative α angle and d α angle at 12 months FU: observe the normalization of the angle and the absence of head/neck deformity. Remodeling, due to the growth, eliminated the bump of the neck evident in the postoperative radiogram (c) (case 16 in Tables 1 and 2)

Post-operation and at the 12-month follow-up, limb length discrepancy was clinically measured (from anterior iliac superior spine to tibial malleolus) and differences between the affected and unaffected sides noted.

All measurements were independently determined by two observers (FF and AGA), and inter-observer correlations were evaluated by chi-square test.

Outcome criteria

Clinical follow-up assessment of the hip was made using the modification by Zahrawi et al. (1983) [25] of the classification of Heyman and Herndon (1954) [26] in which an excellent result has a normal range of hip movement, no limp, no pain, and leg shortening of < 1 cm. A good result had slight limitation of internal rotation, occasional pain, and leg shortening of < 1 cm. A fair result had persistent mild pain, loss of internal rotation, abduction, and leg shortening of > 1 cm. A poor result did not meet any of the above criteria. (We preferred this classification to the Harris Hip Score because it included leg shortening. We believe this is one parameter that must be considered and compared with traditional screw fixation in other papers.)

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used for the variables of our cohort. The paired Student’s t test was used to analyze the differences between a normal hip and a pathologic hip when the data was parametric, and the Pearson correlation was used to correlate the results with the collected data. Outcome data for each group are presented as the mean and standard deviation. The mean difference between groups and a 95% confidence interval are provided. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 computer software.

Results

Between 2000 and 2011, we treated 38 patients with a unilateral mild SCFE by fixation in situ using Guzzanti’s method [19]. Twenty-four patients, 7 females and 17 males, with a mean age of 12.7 years (min 11–max 14.8) met the inclusion criteria (Table 1).

There were 20 stable and 4 unstable hips. No SCFE was noted on the contralateral side in this group during the 12 months post operation. There was no evidence of avascular necrosis or chondrolysis. There were no cases of hardware failure. There was no evidence of slip progression in any patient. The time from presentation to surgery for those with an unstable slip was from 12 to 24 h. Spontaneous reduction of the slip in all 4 unstable cases followed positioning the patient with the hip in extension and neutral rotation.

All measurements were independently determined by two observers (FF and AGA). Inter-observer correlations (using chi-square tests) were evaluated and no significant statistical differences were observed. The data tables reported are the mean value between the two observers.

The mean α angle immediately after pinning on the AP view was 56.2 ± 10.6° and on the lateral view 91.4 ± 8.2°.

At the 6-month follow-up, the α angle of the affected hip compared with the control (contralateral unaffected hip) was statistically significantly different with a p = 0.0001. The mean differences of 6° on the AP and 10° on lateral radiograms had an improvement of about 10° and 40°, respectively (Table 1).

At 12 months, the α angle compared with control was statistically significantly different (p = 0.002), the difference being 2.5° on the lateral radiogram.

On AP radiograms, there was no statistically significant difference observed between the involved and uninvolved sides (p = 0.1). (Table 1) (Figs. 1 and 2).

No closure of the growth plate was observed at 12 months in these cases.

A limb length discrepancy of ≤ 1 cm (the affected limb was shorter) was recorded after operation and confirmed at the follow-up in nine cases (numbers 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15), and in two cases, the affected limb was longer (numbers 19 and 22). There were no statistically significant differences between groups (p = 0.08) (Table 2).

As growth of the femoral neck progressed, the screw advanced into the femoral neck from the lateral femoral cortex, closing the gap between the lateral femoral cortex and the screw head (Figs. 1 and 2).

Neck length after operation showed statistically significant differences between the affected and unaffected sides (p = 0.001) with a mean difference of 0.7 mm, a coefficient of correlation of 0.99, and a p value < 0.0001. At the 12-month follow-up, neck length showed statistically significant differences between the affected and non-affected sides (p = 0.02) with a mean difference of 0.5 mm, a coefficient of correlation of 0.99, and a p value < 0.0001. Note the statistically significant differences between T = 0 and T = 12 months (p < 0.001). This data indicates that the neck grew in the same way on the affected and unaffected sides during the first-year post-treatment (Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2).

Clinical outcome

The clinical results in all patients were rated as excellent and all had resumed full activity at the 6th- and 12th-month post-operation. Limb length discrepancy of ≤ 1 cm (the affected limb was shorter) was recorded post operation and confirmed at follow-up in nine cases (numbers 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15), and in two cases, the affected limb was longer (numbers 19, 22). There were no statistically significant differences between groups (p = 0.08) (Table 2).

No statistically significant differences were observed between affected and unaffected hips in flexion (p = 0.3), extension (p = 0.3), internal rotation (p = 0.3), and external rotation (p = 0.4) and no clinical signs of impingement were detected (Table 2).

Discussion

The data from this study confirm that the femoral neck in patients with mild SCFE can grow after epiphyseal stabilization by a modified screw which does not produce compression on the proximal femoral physis [19]. Premature proximal femoral physeal closure was prevented and potential complications of avascular necrosis and chondrolysis avoided. Screw fixation permitted continued growth of the femoral neck and epiphyseal/physeal complex and remodeling of the epiphysis and metaphysis. This resulted in improvement of the α angle during the first year after stabilization of the epiphysis with significant change noted at 6 months. The improvement observed in the α angle permits to obtain a normal value (that means less than 50°).

Femoral-acetabular impingement (FAI) has been recognized as a cause of hip pain, decreased range of movement, and labral and chondral abnormalities [1,2,3]. Reports of arthroscopic [27, 28] and open [9, 29] evaluation of hips after mild SCFE suggest rates of acetabular cartilage and labral damage between 75 and 100%. Two studies [30, 31] with intermediate follow-up periods of 6.1 to 14.4 years reported hip pain in one third of the patients with slip angles between 0° and 30°. To measure patient activity levels, Tegner and Lysholm knee assessment scores were used, and decreased scores were found in SCFE patients compared to similarly aged counterparts. In mild and moderate slips, computer models [30] demonstrated impaction-type impingement caused by the prominent metaphysis of the neck.

Leunig et al. (2010) [11] believe the ultimate goal of SCFE treatment should be to intervene before irreversible joint injury occurs and that for even mild SCFE, in situ pinning with immediate arthroscopic osteoplasty can reduce or even eliminate hip impingement.

The current standard treatment for mild to moderate SCFE is in situ pinning with stabilization of the slip and premature physeal closure being the primary goals [8]. The premature physeal closure leads to modifications of the epiphyseal–metaphyseal complex which itself becomes a cause of impingement [30, 32]. To avoid this complication, it is necessary to use a type of in situ fixation device which allows continued physeal growth [13, 18,19,20,21]. Immediate arthroscopic osteoplasty as Leunig et al. (2010) [11] proposed might not be necessary if the initial treatment is done using such a device.

In patients from our study, the single modified cannulated screw provided stability and allowed improvement of the pathological epiphyseal/physeal and metaphyseal morphology by allowing for continued physeal growth. Reviewing strictly unilaterally involved patients allowed us to compare proximal femoral growth and development in the affected and unaffected sides. At follow-up, radiological measurements demonstrated a statistically significant (p = 0.01) prolongation in longitudinal femoral neck growth on the involved side. The degree of alteration of the endochondral ossification that would allow for substantial growth and remodeling is unknown. In our series, once the epiphysis was stabilized by our modified screw fixation method, the physis grew in a similar way as the opposite side (Table 2). At the 12-month follow-up, no physeal closures were present.

The study limitations are as follows: (a) a comparison with standard screw fixation cohorts, as we considered only the results reported in other papers [8, 30, 32]; (b) short follow-up; and (c) the considered cohort only affected by mild slip.

Conclusions

The modified screw fixation device used in our study provided stability, neck growth, and physeal junction remodeling during treatment for mild SCFE in the first period (positive progress observed as early as the 6-month follow-up). By restoring the physiology of the proximal femoral anatomy, potential femoroacetabular impingement was prevented.

Abbreviations

- AP:

-

Anteroposterior

- FAI:

-

Femoro-acetabular impingement

- PSA:

-

Posterior sloping angle

- SCFE:

-

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

References

Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1012–8.

Ito K, Minka MA 2nd, Leunig M, Werlen S, Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement and the cam-effect: a MRI-based quantitative anatomical study of the femoral head-neck offset. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:171–6.

Philippon MJ, Maxwell RB, Johnston TL, Schenker M, Briggs KK. Clinical presentation of femoroacetabular impingement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1041–7.

Boyer DW, Mickelson MR, Ponseti IV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: long-term follow-up study of one hundred and twenty-one patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63-A:85–95.

Kulick RG, Denton JR. A retrospective study of 125 cases of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1982;162:87–90.

Carney BT, Weinstein SL, Noble J. Long-term follow-up of slipped femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73-A:667–73.

Seller K, Wild AT, Westhoff B, Raab P, Krauspe R. Radiological evaluation of unstable (acute) slipped capital femoral epiphysis treated by pinning with Kirschner wires. JPediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:328–34.

Ward WT, Stefko J, Wood KB, Stanitski CL. Fixation with a single screw for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74-A:799–809.

Leunig M, Casillas MM, Hamlet M, Hersche O, Notzli H, Slongo T, Ganz R. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: early mechanical damage to the acetabular cartilage by a prominent femoral metaphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:370–5.

Leunig M, Fraitzl CR, Ganz R. Early damage to the acetabular cartilage in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: therapeutic consequences. Orthopade. 2002;31:894–9. (in German)

Leunig M, Horowitz K, Manner H, Ganz R. In situ pinning with arthroscopic osteoplasty for mild SCFE. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:3160–7.

Menelaus M. The management of limb inequality. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.

Leblanc E, Bellemore JM, Cheng T, Little DG, Birke O. Biomechanical considerations in slipped capital femoral epiphysis and insights into prophylactic fixation. J Child Orthop. 2017;11:120–7.

Ricciardi BF, Fabricant PD, Fields KG, Poultsides L, Zaltz I, Sink EL. What are the demographic and radiographic characteristics of patients with symptomatic extraarticular femoroacetabular impingement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:1299–308.

Hansson G, Nathorst-Westfelt J. Management of the contralateral in patients with unilateral slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94-B:596–602.

Guzzanti V, Falciglia F, Stanitski CL, Stanitski DF. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: physeal histologic features before and after fixation. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):571–7.

Falciglia F, Aulisa AG, Giordano M, Boldrini R, Guzzanti V. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an ultrastructural study before and after osteosynthesis. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:331–6.

Hansson LI. Osteosynthesis with the hook-pin in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53:87–96.

Guzzanti V, Falciglia F, Stanitski CL. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86-B:731–6.

Wensaas A, Svenningsen S. Behandling av epiphysiolysis capitis femoris med spesialkonstruert collumskrue. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2005;125(20):2788–90.

Sailhan F, Courvoisier A, Brunet O, Chotel F, Berard J. Continued growth of the hip after fixation epiphysis using a single cannulated screw with a proximal threading. J Child Orthop. 2011;5:83–8.

Clohisy JC, Carlisle JC, Beaulé PE, Kim YJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ, Leunig M, Schoenecker PL, Millis MB. A systematic approach to the plain radiographic evaluation of the young adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg[Am]. 2008;90Suppl 4:47–66.

Guzzanti V, Falciglia F. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: comparison of a roentgenographic method and computed tomography in determining slip severity. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:6–12.

Pollard TC, Villar RN, Norton MR, Fern ED, Williams MR, Simpson DJ, Murray DW, Carr AJ. Femoroacetabular impingement and classification of the cam deformity: the reference interval in normal hips. Acta Orthop. 2010;1:134–41.

Zahrawi F, Stephens T, Spencer G, Clough J. Comparative study of pinning in situ and open epiphysiodesis in 105 patients with slipped femoral capital epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1983;177:160–8.

Heyman CH, Herndon CH. Epiphysiodesis for early slipping of the femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36-A:539–55.

Tannast M, Goricki D, Beck M, Murphy SB, Siebenrock KA. Hip damage occurs at the zone of femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:273–80.

Ilizaliturri VM Jr, Nossa-Barrera JM, Acosta-Rodriguez E, Camacho-Galindo J. Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement secondary to paediatric hip disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1025–30.

Sink EL, Zaltz I, Heare T, Dayton M. Acetabular cartilage and labral damage observed during surgical hip dislocation for stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;1:26–30.

Dodds MK, McCormack D, Mulhall KJ. Femoroacetabular impingement after slipped capital femoral epiphysis: does slip severity predict clinical symptoms? J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:535–9.

Fraitzl CR, Kafer W, Nelitz M, Reichel H. Radiological evidence of femoroacetabular impingement in mild slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a mean follow-up of 14.4 years after pinning in situ. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1592–6.

Mamisch TC, Kim YJ, Richolt JA, Millis MB, Kordelle J. Femoral morphology due to impingement influences the range of motion in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop RelatRes. 2009;467:692–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emeritus Professor, Carl Stanitski, MD for his suggestions. We thank Dr. Alessandro Martinelli for his collaboration in the review process of this article.

Funding

None of the authors have received any funding or economical support for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with respect to the Helsinki Declaration, and all the participants (parents) signed an informed consent to allow the use of clinical data for research purposes. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù in Rome, Italy. Approval reference 8902C85.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Falciglia, F., Aulisa, A.G., Giordano, M. et al. Fixation in slipped capital femoral epiphysis avoiding femoral-acetabular impingement. J Orthop Surg Res 12, 163 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0663-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0663-3