Abstract

Background

This retrospective German and Italian multicenter analysis aimed to compare the role of normofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (nFSRT) to CyberKnife-based hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (CK-hFSRT) for skull base meningiomas.

Methods

Overall, 341 patients across three centers were treated with either nFSRT or CK-hFSRT for skull base meningioma. Treatment planning was based on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) following institutional guidelines. Most nFSRT patients received 33 × 1.8 Gy, and most CK-hFSRT patients received 5 × 5 Gy. The median follow-up time was 36 months (range: 1–232 months).

Results

In the CK-hFSRT group, the 1-, 3-, and 10-year local control (LC) rates were 99.4, 96.8, and 80.3%, respectively. In the nFSRT group, the 1-, 3-, and 10-year LC rates were 100, 99, and 79.1%, respectively. There were no significant differences in LC rates between the nFSRT and CK-hFSRT groups (p = 0.56, hazard ratio = 0.76, 95% confidence interval, 0.3–1.9). In the CK-hFSRT group, only one case (0.49%) of severe toxicity (CTCAE 4.0 ≥ 3) was observed. In the nFSRT group, three cases (2.1%) of grade III toxicity were observed.

Conclusion

This analysis of pooled data from three centers showed excellent LC and low side effect rates for patients treated with CK-hFSRT or nFSRT. The efficacy, safety, and convenience of a shortened treatment period provide a compelling case for the use of CK-hFSRT in patients with moderate size skull base meningioma and provided that OAR constraints are met.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Treating skull base meningioma using traditional surgical methods is difficult because of its close proximity to critical structures such as the cranial nerves, brainstem, and major blood vessels (including the cavernous sinus and carotid arteries). Historically, a surgical approach with the aim of gross total resection (GTR) was considered the gold standard in symptomatic patients. Arguments in favor of the surgical approach include instant reduction of the mass effect as well as risk of false diagnosis of tumor type and grade in patients without surgery where no tissues were obtained. However, complete surgical removal is often difficult to achieve without compromising the intricate neuroanatomic structure of the skull base and the risk of local relapse following incomplete resection without adjuvant treatment is high. Also, morbidity following surgery is high especially in the elderly patients where there is a significant rate of post-surgery mortality [1, 2].

Radiotherapy (RT) is a potential alternative for definitive treatment, and plays a role in the adjuvant situation after incomplete resection of grade I meningiomas as well as after complete or incomplete resection of grade II and III meningiomas. Traditional radiotherapeutic approaches consisted of normofractionated stereotactic RT (nFSRT) but recent availability of high-precision devices including the CyberKnife and Gamma Knife in first world have resulted in both hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (hFSRT) and radiosurgery (SRS) to become a fast, safe and convenient alternative approach [3,4,5,6,7].

Traditional nFSRT takes advantage of the differing cell repair potentials of tumor versus healthy tissue in an elegant fashion, by allowing for the healthy tissue to repair in the interval between two treatments it is possible to achieve a broad therapeutic window. On the other hand, in hFSRT and SRS treatment approaches higher single doses are applied, thus requirements for conformity and steepness of dose gradient are increased, especially if the treatment volume is in close proximity to organs at risk (OAR) [1, 8, 9].

This retrospective German and Italian multicenter pooled analysis aimed to evaluate the role of CyberKnife-based hFSRT in the treatment of skull base meningioma cases as compared to a normofractionated cheme of stereotactic irradiation.

Methods

Patient selection and tumor characteristics

We retrospectively reviewed our clinical databases, and collected data on patients treated between October 1995 and November 2018 across three institutions. Patients examined in this study were pooled from the Department of Radiation Oncology at [blinded], the CyberKnife Center at [blinded], and the CyberKnife Center at [blinded]. Patients were included if they had undergone radiotherapy of a skull base meningioma excluding those who received a single fraction stereotactic treatment. Diagnosis had to be made either histologically or through imaging-based approaches.

Ethics

The study was approved by our local ethics committees in Italy and Germany.

Stereotactic hypofractionated radiotherapy/radiosurgery at our centers in Germany and Italy

Treatments were delivered using the CyberKnife (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA), an image-guided, frameless, Linac-based, 6 MV radiosurgery system [5, 10, 11]. The patient’s head was immobilized with a thermoplastic mask during planning computed tomography (CT) and treatment. During treatment, patient positions were monitored with orthogonal x-ray images approximately every minute.

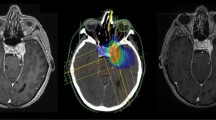

For planning purposes, a high-resolution contrast-enhanced thin-slice head CT was performed using a multi-slice CT scanner. Additionally, thin-section, contrast-enhanced, T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. Contouring of the tumor volume and the critical structures were performed on the co-registered MRI and CT dataset using the MultiPlan software (Accuray Inc., USA).

Manual contouring was done in the axial slices with simultaneous display of contours on reconstructed orthogonal images. The gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined as the tumor volume based on CT and MRI, and no safety margin was added. The selection of the marginal and maximal doses and the number of sessions were influenced by multiple factors including tumor volume, adjacency to organs at risk (optic nerve, chiasm, and brainstem) as well as the area that previously received irradiation. The ray-tracing algorithm was routinely used for nonisocentric beam delivery. The dose was prescribed to the median prescription isodose line covering the GTV was 75%. Dose constraints to organs at risk (OAR) for five fractions of CK-hFSRT were as follows: ≤0.2 cm3 of the optic pathway could receive 23.0 Gy with a maximum point dose of 25.0 Gy in ≤0.035 cm3 and ≤ 0.5 cm3 of the brainstem could receive 23.0 Gy with a maximum point dose of 31 Gy in ≤0.035 cm3 [12].

Stereotactic radiotherapy at our department in Germany

From 1995 to 2003, meningioma patients underwent “sharp” fixation using a stereotactic head ring and an oral bite plate. A 6-MV Linac (Varian Medical Systems, USA) with an add-on micro multi-leaf collimator (BrainLAB, Germany) was used. Coordinates for SRS were set by a laser-based stereotactic localizer. This setup allowed delivering shaped beams. In 2004, the department started using NovalisTx with beam shaping capability using built-in MLC and image guidance with ExacTrac (Varian Medical Systems, USA and BrainLAB, Germany). The image-guided frameless system enabled us to image the patient at any couch position using a frameless positioning array. A three-dimensional treatment planning based on CT and co-registered MRI was done with Brainscan (BrainLAB, Germany), which was later replaced by iplanRT (BrainLAB, Germany). The GTV was defined as the area of contrast enhancement on T1-weighted MR images and the planning target volume (PTV) included a 1–2 mm isotropic safety margin. The dose was prescribed to a reference point, representing 100%. Patients received 95% of the prescribed dose at the PTV margin. Dose constraints for OAR were as follows: optic nerves, chiasma, and brainstem could receive maximal 54 Gy according to Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC) [13].

Algorithms

Meningioma localization was classified according to the new CLASS algorithmic scale: In their publication Lee et al. classified tumor location based on the experience of the senior author. “Low-risk” locations included convexity and lateral skull base (lateral and middle sphenoid wing, posterior petrous). Olfactory groove, planum sphenoidale, tentorial (lateral/paramedian), parasagittal, intraventricular, cerebellopontine angle, falcine, posterior/lateral foramen magnum as well as para-sigmoid and para-transverse sinus locations constituted the “moderate risk” group. The “high-risk” locations included clinoidal, cavernous sinus, tuberculum sellae, tentorial (medial/incisural), ventral petrous, petroclival and anterior/anterolateral foramen magnum [14].. Meningiomas of the optical nerve sheath were not included in the original CLASS algorithmic scale, in the presented work they were classified as high-risk.

Calculation of doses equivalence

Calculations of equivalent doses of radiation to normofractionation (EQD2) and biologically effective dose (BED) were based on a radiobiological model previously described [5]. In brief, we analyzed the clinical data available in the literature on meningioma irradiation. We then selected two different dose/fraction schemes that resulted in similar tumor control rates. According to our evaluations, 13 Gy in single fraction provides LC rates that are similar to 54 Gy in 30 fractions for meningiomas. Using the LQ model, it is then possible to calculate the α/β of meningiomas. Actually, if the BED of these two schedules of irradiation are equivalent, we can infer that the α/β of meningiomas is equal to 2 [5].

Follow-up and data collection

All patients underwent serial radiological evaluations and, in selected cases, endocrinological and ophthalmological examinations. The first follow-up examination usually occurred 6 months after treatment. Radiological assessment consisted of contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI in all cases.

Patients were followed up after treatment at the three departments in 3–6-month intervals for the first year. From the second year on, follow-up intervals were extended to 6–12 months, or as required clinically. We included the latest available follow-up in this analysis. Progression-free survival (PFS as local control [LC]) was determined based on the respective radiologist’s judgement. Treatment of progressing tumors was discussed in multidisciplinary tumor boards.

Statistical analysis

The patient and tumor characteristics were compared between the two treatment groups using the chi-squared test (categorical variables) or Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the PFS probabilities from the last day of RT. Univariate analyses was performed using Cox regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant for this study.

Results

Patient cohort

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 341 patients were enrolled in this study, 49 patients enrolled from [blinded], 136 patients enrolled from [blinded], and 156 patients enrolled from [blinded]. Median follow-up time to last contact or progress on MRI was 36 months (range 1–232 months). Two hundred and five patients received CK-hFSRT and 136 patients received nFSRT treatments. Compared with 41.9% of nFSRT patients, approximately two-thirds of CK-hFSRT patients received definitive radiotherapy at primary diagnosis (65.9%).

Radiation doses and schedules

Radiotherapy parameters for the two groups are shown in Table 2. Several fractionation regimens were used in both groups, the most common being 5 × 5 Gy in the CK-hFSRT group and 33 × 1.8 Gy in the nFSRT group. The mean GTV was significantly lower in the CK-hFSRT group than in the nFSRT group (10.1 ± 11.9 ccm vs. 25.1 ± 31.2 ccm, p < 0.001). In the CK-hFSRT group, the mean single dose was 5.2 ± 0.9 Gy, median dose per fraction was 5 Gy, mean prescribed total dose was 24.6 ± 4.9 Gy, and median prescribed total dose was 25 Gy (Fig. 1).

In the nFSRT group, the mean single dose was 1.8 ± 0.1 Gy, median dose per fraction was 1.8 Gy, mean total dose was 56.9 ± 4.2 Gy, and median total dose was 59.4 Gy. The mean BED2 was significantly lower in the CK-hFSRT group (88.1 ± 16.3 vs. 108.5 ± 7.5, p < 0.001). The mean EQD22 was also significantly lower in the CK-hFRST group (44.1 ± 8.1 Gy vs. 54. 2 ± 3.8 Gy, p < 0.001).

LC

In the overall cohort, the 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year LC rates were 99.6, 97.3, 91.6, and 78.4%, respectively. There were no significant differences in LC rates between the nFSRT and CK-hFSRT groups (p = 0.56, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3–1.9, Fig. 2). In the CK-hFSRT group, the 1-, 3-, and 10-year LC rates were 99.4, 96.8, and 80.3%, respectively. In the nFSRT group, the 1-, 3-, and 10-year LC rates were 100, 99, and 79.1%, respectively.

The largest volume treated in the CK-hFSRT group was 76.2 ccm. When only examining patients with a GTV ≤76.2 ccm in the nFSRT group (n = 92), there was still no significant difference with regard to LC-rates compared to the CK-hFSRT group (p = 0.17, HR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.13–1.42).

Interestingly no relapse was seen in the cohort of patients treated with definitive nFSRT (Fig. 3). Due to the relatively small number of patients with long term follow-up in the subgroups no significant differences were seen between the CK-hFSRT with definitive treatment and the nFSRT with definitive treatment groups (p = 0.32, HR = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.0–40.2).

No relapses were seen in the cohort of patients treated with definitive nFSRT. However, due to the small number of patients with long term follow-up no significant differences were observed between the CK-hFSRT with definitive treatment and the nFSRT group with definitive treatment (p = 0.32, HR = 0.02, 95% CI, 0.0–40.2)

Atypical meningioma were excluded from this analysis, even though a large group of patients the histological diagnosis was only supposed on the base of clinical behavior and imaging. Nevertheless, we did not find any correlation between patients for whom histology was available vs. no-histology group in terms of LC or progression free survival.

Toxicity

Toxicity following RT was very low in both treatment groups. After CK-hFSRT a total of 16 patients (7.8%) had new mild (CTCAE I°) or moderate (CTCAE II°) cranial neuropathy. CTCAE II° trigeminal neuralgia was the most common cranial neuropathy (6.3%). Besides trigeminal neuralgia, cranial deficits in the CK-hFSRT group included one case (0.49%) of mild (CTCAE I°) visual disturbance in a patient with a clival lesion and one mild (CTCAE I°) case of third and sixth cranial nerve deficits in a patient with a spheno-petro-clival meningioma. One case (0.49%) of therapy-associated carotid artery occlusion was reported in a patient with a large spheno-petro-clival meningioma encasing the carotid artery, which resulted in a transient facial nerve (CTCAE III°) deficit. No new seizure onset was reported. in all patients who presented major complications the side effect was attributed to encasement of cranial nerves or vascular structures.

In the nFSRT treatment group, 12 patients (8.8%) had new mild or moderate (CTCAE ≤ II°) cranial neuropathy with four patients (2.9%) that developed mild (CTCAE I°) and one patient (0.7%) that developed moderate (CTCAE II°) optical pathway toxicity. Four patients (2.9%) had mild (CTCAE I°) and one patient (0.7%) had moderate (CTCAE II°) hearing impairment. One patient (0.7%) had mild and two patients (1.47%) had moderate (CTCAE II°) trigeminal neuralgia. Four patients (2.9%) developed mild (CTCAE I°) and one patient (0.7%) developed moderate (CTCAE II°) cranial nerve sensory deficits. One case (0.7%) of an acute grade III brain edema was seen and two cases (1.5%) of severe (CTCAE III°) vascular stenosis were seen both potentially linked to radiotherapy. Additionally, one patient (0.7%) developed new seizures (CTCAE II°).

Discussion

We collected a large cohort of patients with skull base meningioma and provided a unique comparison between conventionally fractionated and hypofractionated radiotherapy approaches. This was done in order to shed light on the therapeutic potential of hFSRT in meningiomas that are not suitable for single fraction radiosurgery and are generally treated by nFSRT. Our retrospective analysis did not find a significant difference in LC-rates between the two groups (p = 0.56, HR = 0.76, 95% CI, 0.3–1.9). In general LC rates were satisfactory and comparable to those of single-fraction SRS or surgical treatment approaches [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Indeed, 10-year survival rates were close to 80% in both groups. Toxicities were limited and comparable between the groups suggesting a beneficial risk-benefit profile for both techniques in these patients.

Single-fraction SRS has been widely used as a treatment alternative to surgical resection, for small-to-moderate volume skull base meningiomas without close proximity to radiosensitive structures while the use of conventionally fractionated RT is more common in larger meningiomas that are not suitable for surgery [15,16,17, 21, 22]. LC rates in fractionated regimens range between 80 and 100%, depending on the size of the lesions, location, dose applied, and length of follow-up [4, 8, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The results of several studies directly comparing the outcomes of nFSRT and SRS suggest that both are safe and effective techniques for treating skull base meningiomas and provide comparable satisfactory long-term tumor control [38,39,40,41]. In a multicenter pooled analysis of skull bases meningiomas Combs et al. compared 119 patients who received single fraction SRS to 808 patients who received nFSRT and showed significantly worse LC rates for the SRS treated patients using univariate analysis. This was also true when comparing only patients with smaller volumes (< 47.0 cc). However, these differences in LC were not seen after multivariate analysis [36]. The authors concluded that SRS is an alternative to nFSRT. However, following the Combs et al. study doubts remained in the neuro-oncology community regarding whether single fraction SRS is an adequate option for skull bases meningioma due to the lower LC rates for SRS in the univariate analysis.

According to current practice guidelines, the main criteria for selecting between FSRT and SRS are the average diameter of the meningioma, clearly recognizable tumor margins, and close proximity to radiation-sensitive structures. Effectiveness of SRS is seemingly reduced in larger tumors > 7.5 cc [42], and the risk-benefit ratio becomes unfavorable in these patients. Similarly, SRS is unfavorable in patients with tumors lying less than 3–5 mm away from radiosensitive structures, especially the anterior optic pathway. Some authors have therefore suggested the use of hFSRT for these cases, utilizing many of the same platforms used for SRS [10, 43,44,45,46,47,48]. In 2018, Meniai-Merzouki et al. revealed LC rates of 81% after 24 months in 96 patients who received CK-hFSRT as a primary treatment. This cohort included 57 patients who received definitive RT, ten patients who received adjuvant RT, and 29 patients who received RT after local progression after prior surgery alone [44]. These LC rates are a bit lower than the ones shown in the current study and reasons for this difference remains unclear.

Unger and colleagues reported on 173 patients with meningiomas where 56% underwent single fraction SRS with Gamma Knife, while the remaining patients received CK-hFSRT using two to five fractions [48]. The median dose for SRS was 15 Gy and the usual regimen was 25 Gy in five fractions for hFSRT. Two-year risk of symptomatic edema was 3.2% for multisession stereotactic radiation therapy, and 12.5% for SRS. Tumor size greater than 4.9 cc was also a significant predictor of symptomatic edema [48]. HFSRT has been typically adopted for the treatment of perioptic meningiomas. Midterm follow-up data on multisession radiosurgery of perioptic meningiomas have been reported [5, 45, 47, 49,50,51,52,53] with encouraging results showing tumor control rates > 90% with very limited toxicity to the anterior optic pathway. The authors were able to show that treatment of meningiomas in proximity or even encasing the optic nerve and chiasm by hFSRT is possible with a limited risk of radio-induced optic neuropathy that occurred only in 0–5% of cases [5, 47]. Nevertheless, especially in meningiomas in direct contact with the anterior optic pathway, the sensitivity of blood supply of the optical system must be considered; a vascular damage could lead to secondary late toxicity and thus loss of vision as result of high-dose fractions. On the other hand, a suboptimal dose can cause a visual function deterioration as a result of tumor progression [53]. If we look to our overall data, patients treated with hFSRT had mostly lesions with volumes ranging 8–25 cc or with a close relationship to critical structures, whereas nFSRT was adopted in larger tumors or in those encasing the optic apparatus. We can consider this a balanced indication for treatment strategy. Furthermore, in patients who presented major complications after hFSRT, these were attributed to encasement of or proximity to cranial nerves or vascular structures. Accordingly, due to the relative inhomogeneity of hFSRT as compared to nFSRT, encasement of critical structures, i.e. in optic nerve sheath meningiomas, should be considered as a factor in favor of nFSRT to avoid hot spots inside the GTV [54]. On the other hand, because of better conformal dose distribution, hFSRT would be a better choice in tumor adjacent to very sensitive OAR like perioptic meninigiomas.

A point deserving a comment is the difference of BED between nFSRT and hFSRT in this series. Indeed, nFSRT had a median BED of 113 Gy2 versus 87.5 Gy2 in hFSRT treatments. This can be explained on the base of a higher confidence with normofractionation about toxicity whereas a more conservative approach was adopted with a hypofractionated scheme. Notheworthy, the lower BED of hFSRT was sufficient to reach a similar level of LC suggesting that a similar BED is sufficient to warrant efficacy and confirming previous data [5, 45].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective approach is prone to bias, including potential cases where patients with relapse may seek treatment from a different healthcare provider, due to frustration with results of the previous treatment. Such instances may provide potential confounders that lead to the loss of follow-up data especially in patients that suffer from relapse. Second, the fractionation schedules and BEDs are heterogeneous within the two cohorts. Third, the cohorts are heterogeneous in such a way that they comprise patients who received radiotherapy in a definitive setting, both at primary diagnosis or at relapse and also in patients who received RT in an adjuvant setting.

Fourth, a significant subset of patients did not receive a histological verification of the diagnosis. Finally, some concerns remain about the very long-term toxicity of hFSRT – since these data are not available yet.

However, to our knowledge this is the first multicenter analysis comparing CK-hFSRT and nFSRT. We showed excellent LC and low side effects rates for patients treated with CK-hFSRT and nFSRT. The efficacy and safety, at least at the mid-term (i.e. 10 years), as well as convenience for patients is a strong argument for the use of CK-hFSRT in patients suffering from selected skull base meningioma.

Conclusion

In summary, this analysis of pooled data from three centers showed excellent LC and low side effect rates for patients treated with CK-hFSRT or nFSRT. The efficacy, safety, and convenience of a shortened treatment period provide a compelling case for the use of CK-hFSRT in patients with skull base meningioma of moderate size and provided that OAR constraints are met.

Availability of data and materials

Data in the manuscript are available by contacting the corresponding author.

Change history

14 December 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

References

Kaul D, Badakhshi H, Gevaert T, Pasemann D, Budach V, Tuleasca C, Gruen A, Prasad V, Levivier M, Kufeld M. Dosimetric comparison of different treatment modalities for stereotactic radiosurgery of meningioma. Acta Neurochir. 2015;157:559–63 discussion 563-554.

Grosu AL, Fennell JT. morbidity and mortality due to meningioma after cranial radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2018;194:67–9.

Kaul D, Budach V, Misch M, Wiener E, Exner S, Badakhshi H. Meningioma of the skull base: long-term outcome after image-guided stereotactic radiotherapy. Cancer Radiother. 2014;18:730–5.

Kaul D, Budach V, Wurm R, Gruen A, Graaf L, Habbel P, Badakhshi H. Linac-based stereotactic radiotherapy and radiosurgery in patients with meningioma. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:78.

Conti A, Pontoriero A, Midili F, Iati G, Siragusa C, Tomasello C, La Torre D, Cardali SM, Pergolizzi S, De Renzis C. CyberKnife multisession stereotactic radiosurgery and hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for perioptic meningiomas: intermediate-term results and radiobiological considerations. Springerplus. 2015;4:37.

Nutting C, Brada M, Brazil L, Sibtain A, Saran F, Westbury C, Moore A, Thomas DG, Traish D, Ashley S. Radiotherapy in the treatment of benign meningioma of the skull base. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:823–7.

O’Steen L, Amdur RJ, Morris CG, Mendenhall WM. Challenging the concept that late recurrence and death from tumor are common after fractionated radiotherapy for benign meningioma. Radiother Oncol. 2019;137:55–60.

Combs SE, Ganswindt U, Foote RL, Kondziolka D, Tonn JC. State-of-the-art treatment alternatives for base of skull meningiomas: complementing and controversial indications for neurosurgery, stereotactic and robotic based radiosurgery or modern fractionated radiation techniques. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:226.

Moustakis C, Chan MKH, Kim J, Nilsson J, Bergman A, Bichay TJ, Palazon Cano I, Cilla S, Deodato F, Doro R, et al. Treatment planning for spinal radiosurgery : a competitive multiplatform benchmark challenge. Strahlenther Onkol. 2018;194:843–54.

Conti A, Pontoriero A, Siddi F, Iati G, Cardali S, Angileri FF, Granata F, Pergolizzi S, Germano A, Tomasello F. Post-treatment edema after meningioma radiosurgery is a predictable complication. Cureus. 2016;8:e605.

Conti A, Pontoriero A, Salamone I, Siragusa C, Midili F, La Torre D, Calisto A, Granata F, Romanelli P, De Renzis C, Tomasello F. Protecting venous structures during radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27:E11.

Benedict SH, Yenice KM, Followill D, Galvin JM, Hinson W, Kavanagh B, Keall P, Lovelock M, Meeks S, Papiez L, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy: the report of AAPM task group 101. Med Phys. 2010;37:4078–101.

Marks LB, Yorke ED, Jackson A, Ten Haken RK, Constine LS, Eisbruch A, Bentzen SM, Nam J, Deasy JO. Use of normal tissue complication probability models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S10–9.

Lee J, Sade B. The Novel “CLASS” Algorithmic Scale for Patient Selection in Meningioma Surgery. In Meningiomas. In: Lee J, editor. . London: Springer; 2009. p. 217–21.

Stafford SL, Pollock BE, Foote RL, Link MJ, Gorman DA, Schomberg PJ, Leavitt JA. Meningioma radiosurgery: tumor control, outcomes, and complications among 190 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1029–37 discussion 1037-1028.

Seo Y, Kim DG, Kim JW, Han JH, Chung HT, Paek SH. Long-term outcomes after gamma knife radiosurgery for benign meningioma: a single Institution's experience with 424 patients. Neurosurgery. 2018;83:1040–9.

Kim JW, Kim DG, Se YB, Kim SK, Chung HT, Paek SH, Jung HW. Gamma knife radiosurgery for Petroclival meningioma: long-term outcome and failure pattern. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2017;95:209–15.

Cohen-Inbar O, Tata A, Moosa S, Lee CC, Sheehan JP. Stereotactic radiosurgery in the treatment of parasellar meningiomas: long-term volumetric evaluation. J Neurosurg. 2018;128:362–72.

Cohen-Inbar O, Lee CC, Sheehan JP. The contemporary role of stereotactic radiosurgery in the treatment of Meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016;27:215–28.

Kondziolka D, Patel AD, Kano H, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Long-term outcomes after gamma knife radiosurgery for Meningiomas. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:453–7.

Faramand A, Kano H, Niranjan A, Johnson SA, Hassib M, Park KJ, Arai Y, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Cranial nerve outcomes after primary stereotactic radiosurgery for symptomatic skull base meningiomas. J Neuro-Oncol. 2018;139:341–8.

Sheehan JP, Starke RM, Kano H, Kaufmann AM, Mathieu D, Zeiler FA, West M, Chao ST, Varma G, Chiang VL, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for sellar and parasellar meningiomas: a multicenter study. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:1268–77.

Combs SE, Adeberg S, Dittmar JO, Welzel T, Rieken S, Habermehl D, Huber PE, Debus J. Skull base meningiomas: long-term results and patient self-reported outcome in 507 patients treated with fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT) or intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Radiother Oncol. 2013;106:186–91.

Solda F, Wharram B, Gunapala R, Brada M. Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy for optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2012;24:e106–12.

Steinvorth S, Welzel G, Fuss M, Debus J, Wildermuth S, Wannenmacher M, Wenz F. Neuropsychological outcome after fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT) for base of skull meningiomas: a prospective 1-year follow-up. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69:177–82.

Fokas E, Henzel M, Surber G, Hamm K, Engenhart-Cabillic R. Stereotactic radiation therapy for benign meningioma: long-term outcome in 318 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:569–75.

Andrews DW, Faroozan R, Yang BP, Hudes RS, Werner-Wasik M, Kim SM, Sergott RC, Savino PJ, Shields J, Shields C, et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for the treatment of optic nerve sheath meningiomas: preliminary observations of 33 optic nerves in 30 patients with historical comparison to observation with or without prior surgery. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:890–902 discussion 903-894.

Astner ST, Theodorou M, Dobrei-Ciuchendea M, Auer F, Kopp C, Molls M, Grosu AL. Tumor shrinkage assessed by volumetric MRI in the long-term follow-up after stereotactic radiotherapy of meningiomas. Strahlenther Onkol. 2010;186:423–9.

Milker-Zabel S, Zabel-du Bois A, Henze M, Huber P, Schulz-Ertner D, Hoess A, Haberkorn U, Debus J. Improved target volume definition for fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy in patients with intracranial meningiomas by correlation of CT, MRI, and [68Ga]-DOTATOC-PET. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:222–7.

Jeremic B, Pitz S. Primary optic nerve sheath meningioma: stereotactic fractionated radiation therapy as an emerging treatment of choice. Cancer. 2007;110:714–22.

Pacelli R, Cella L, Conson M, Tranfa F, Strianese D, Liuzzi R, Solla R, Farella A, Salvatore M, Bonavolonta G. Fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy for orbital optic nerve sheath meningioma - a single institution experience and a short review of the literature. J Radiat Res. 2011;52:82–7.

Afshar-Oromieh A, Wolf MB, Kratochwil C, Giesel FL, Combs SE, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Gnirs R, Roethke MC, Schlemmer HP, Haberkorn U. Comparison of (6)(8)Ga-DOTATOC-PET/CT and PET/MRI hybrid systems in patients with cranial meningioma: initial results. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:312–9.

Farzin M, Molls M, Kampfer S, Astner S, Schneider R, Roth K, Dobrei M, Combs S, Straube C. Optic toxicity in radiation treatment of meningioma: a retrospective study in 213 patients. J Neuro-Oncol. 2016;127:597–606.

Mozes P, Dittmar JO, Habermehl D, Tonndorf-Martini E, Hideghety K, Dittmar A, Debus J, Combs SE. Volumetric response of intracranial meningioma after photon or particle irradiation. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:431–7.

Stade F, Dittmar JO, Jakel O, Kratochwil C, Haberkorn U, Debus J, Combs SE. Influence of (68) Ga-DOTATOC on sparing of normal tissue for radiation therapy of skull base meningioma: differential impact of photon and proton radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:58.

Combs SE, Farzin M, Boehmer J, Oehlke O, Molls M, Debus J, Grosu AL. Clinical outcome after high-precision radiotherapy for skull base meningiomas: pooled data from three large German centers for radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2018;127:274–9.

Kessel KA, Fischer H, Oechnser M, Zimmer C, Meyer B, Combs SE. High-precision radiotherapy for meningiomas : long-term results and patient-reported outcome (PRO). Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193:921–30.

Lo SS, Cho KH, Hall WA, Kossow RJ, Hernandez WL, McCollow KK, Gerbi BJ, Higgins PD, Lee CK, Dusenbery KE. Single dose versus fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for meningiomas. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29:240–8.

Metellus P, Regis J, Muracciole X, Fuentes S, Dufour H, Nanni I, Chinot O, Martin PM, Grisoli F. Evaluation of fractionated radiotherapy and gamma knife radiosurgery in cavernous sinus meningiomas: treatment strategy. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:873–86 discussion 873-886.

Minniti G, Amichetti M, Enrici RM. Radiotherapy and radiosurgery for benign skull base meningiomas. Radiat Oncol. 2009;4:42.

Torres RC, Frighetto L, De Salles AA, Goss B, Medin P, Solberg T, Ford JM, Selch M. Radiosurgery and stereotactic radiotherapy for intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14:e5.

Pollock BE, Stafford SL, Utter A, Giannini C, Schreiner SA. Stereotactic radiosurgery provides equivalent tumor control to Simpson grade 1 resection for patients with small- to medium-size meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1000–5.

Minniti G, Clarke E, Cavallo L, Osti MF, Esposito V, Cantore G, Cappabianca P, Enrici RM. Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy for large benign skull base meningiomas. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:36.

Meniai-Merzouki F, Bernier-Chastagner V, Geffrelot J, Tresch E, Lacornerie T, Coche-Dequeant B, Lartigau E, Pasquier D. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for patients with intracranial Meningiomas: impact of radiotherapy regimen on local control. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13666.

Adler JR Jr, Gibbs IC, Puataweepong P, Chang SD. Visual field preservation after multisession cyberknife radiosurgery for perioptic lesions. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(Suppl 2):733–43.

Girvigian MR, Chen JC, Rahimian J, Miller MJ, Tome M. Comparison of early complications for patients with convexity and parasagittal meningiomas treated with either stereotactic radiosurgery or fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:A19–27 discussion A27–18.

Marchetti M, Bianchi S, Pinzi V, Tramacere I, Fumagalli ML, Milanesi IM, Ferroli P, Franzini A, Saini M, DiMeco F, Fariselli L. Multisession radiosurgery for Sellar and Parasellar benign Meningiomas: long-term tumor growth control and visual outcome. Neurosurgery. 2016;78:638–46.

Unger KR, Lominska CE, Chanyasulkit J, Randolph-Jackson P, White RL, Aulisi E, Jacobson J, Jean W, Gagnon GJ. Risk factors for posttreatment edema in patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery for meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:639–45.

Colombo F, Casentini L, Cavedon C, Scalchi P, Cora S, Francescon P. Cyberknife radiosurgery for benign meningiomas: short-term results in 199 patients. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:A7–13.

Marchetti M, Bianchi S, Milanesi I, Bergantin A, Bianchi L, Broggi G, Fariselli L. Multisession radiosurgery for optic nerve sheath meningiomas--an effective option: preliminary results of a single-center experience. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:1116–22 discussion 1122-1113.

Romanelli P, Bianchi L, Muacevic A, Beltramo G. Staged image guided robotic radiosurgery for optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Comput Aided Surg. 2011;16:257–66.

Romanelli P, Wowra B, Muacevic A. Multisession CyberKnife radiosurgery for optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E11.

Marchetti M, Conti A, Beltramo G, Pinzi V, Pontoriero A, Tramacere I, Senger C, Pergolizzi S, Fariselli L. Multisession radiosurgery for perioptic meningiomas: medium-to-long term results from a CyberKnife cooperative study. J Neuro-Oncol. 2019;143:597–604.

Adeberg S, Welzel T, Rieken S, Debus J, Combs SE. Prior surgical intervention and tumor size impact clinical outcome after precision radiotherapy for the treatment of optic nerve sheath meningiomas (ONSM). Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:117.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Acker is participant of the BIH-Charité Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC provided ideas, collected data and drafted part of the manuscript. DK provided ideas, collected data, performed the statistical analysis drafted part the manuscript and supervised the discussion of the manuscript CS and GA provided ideas, collected patient data and reviewed the manuscript. AK drafted part of the manuscript AP, AC, SP, AG, HB, FM and PM collected patient data and reviewed the manuscript. MK, FL, PV and VB reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DK received travel grants from Accuray. No other competing interest exist.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was acquired from all patients with respect to RT treatment and clinical data management for research purposes. The local ethics board approved the study.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Alfredo, C., Carolin, S., Güliz, A. et al. Normofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy versus CyberKnife-based hypofractionation in skull base meningioma: a German and Italian pooled cohort analysis. Radiat Oncol 14, 201 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1397-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1397-7