Abstract

Background

Primary care practices provide a gate-keeping function in many health care systems. Since depressive disorders are highly prevalent in primary care settings, reliable detection and diagnoses are a first step to enhance depression care for patients. Provider training is a self-evident approach to enhance detection, diagnoses and treatment options and might even lead to improved patient outcomes.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted reviewing research studies providing training of general practitioners, published from 1999 until May 2011, available on the electronic databases Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library as well as national guidelines and health technology assessments (HTA).

Results

108 articles were fully assessed and 11 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included. Training of providers alone (even in a specific interventional method) did not result in improved patient outcomes. The additional implementation of guidelines and the use of more complex interventions in primary care yield a significant reduction in depressive symptomatology. The number of studies examining sole provider training is limited, and studies include different patient samples (new on-set cases vs. chronically depressed patients), which reduce comparability.

Conclusions

This is the first overview of randomized controlled trials introducing GP training for depression care. Provider training by itself does not seem to improve depression care; however, if combined with additional guidelines implementation, results are promising for new-onset depression patient samples. Additional organizational structure changes in form of collaborative care models are more likely to show effects on depression care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depressive disorders are highly prevalent in the general public. The 12-month prevalence of Major Depression among Europeans has shown to be approximately 6.9% while conservative estimates of the lifetime prevalence range up to 14% [1, 2]. Depression is associated with significant functional impairment and reduced quality of life [3, 4], excess mortality rates [5] and particularly high costs for society and health care systems [6–9]. Considering the large effects of the disease on individuals and society, it seems clear that early detection and treatment is a desirable goal in order to promote remission and reduce negative consequences [10].

While 50 to 70 per cent of all depressed patients consult their primary care physician during an episode, therefore making them the profession most likely to be seen [11, 12], depression in primary care remains under-recognised and under-treated [13]. As Bijl and colleagues (2004) summarise, the elements of detection, diagnosis and treatment determine successful depression management in health care. Previous trials showed that approximately 50 per cent of all depressed patients in primary care were not diagnosed as such [14–16]. This is a major downfall in depression care, since even subthreshold depression episodes may be clinically significant [17]. Obviously part of this is due to reluctance to seek treatment among patients themselves, resulting from concerns on effectiveness of treatment and perceived absence of treatment necessity [18].

To objectify diagnoses, the use of screening instruments has been promoted by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, when adequate treatment and care possibilities are available [19]. Reviews showed that screening alone does not improve depression outcomes for patients [20], but needs further organizational changes [21]. These structural interventions, including collaborative care approaches as well as provider training, represent an attempt to increase detection and diagnosis of depressed patients and therefore promote enhanced treatment. Several treatment options that support primary care physicians in treatment and that are also directly delivered by general practitioners (such as PST- problem solving therapy) have been found to be effective for depression [22, 23].

Primary care practices play a central role in many health care systems- this kind of gate-keeping is even associated with improved coordination and outcomes [24]. This circumstance makes general practitioners ideal as a base for first steps in treatment, also referred to as a "stepped care" approach [25]. "Watchful waiting" and low intense interventions such as self-help approaches have to be encouraged as useful strategies [26]. In order to make full use of this opportunity, improvement of detection rates and diagnosis is inevitable. Improving skills of primary care providers can be achieved by different strategies. Consultation-liaison involves a persistent educational supervision of the general practitioner by a mental health specialist. This approach has not been shown to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms [27]. As indicated by Cape et al. (2010), another point of intervention can be to train primary care providers in diagnosis and treatment strategies without the inclusion of mental health specialists (such as collaborative care), considering limited financial resources of health care systems [27]. Moderated by higher detection rates and better knowledge on treatment options, improvement on this level could subsequently lead to higher remission rates in less time and improved depression outcomes.

In the past, these programmes of provider education have been evaluated, yielding unclear results on effectiveness of the intervention regarding health gain outcomes [21]. This study therefore reviews current literature for an updated overview. It is the first overview of randomized controlled trials that exclusively investigates interventions that apply practitioner training.

Methods

Literature Search

This review was prepared according to the systematic literature review guidelines of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [28] and follows PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) suggestions [29]. A systematic literature search was conducted reviewing research studies, published from 1999 until May 2011, available on the electronic databases Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library as well as national guidelines and health technology assessments (HTA). In addition, the bibliographies of the selected articles were searched. Grey literature was not searched. 1999 as a starting point of the search was chosen to include at least the last 10 years of publications. The latest review on this topic, including studies from 1999 onward, was conducted in 2003, and we meant to include those studies as well [21]. The aim was to evaluate if newer, more recent studies would show clearer effects of the intervention than previous overviews.

The terms (depression OR depressive disorder) AND (general practitioner OR general practice OR primary care OR family practice) AND (training OR education) served as search criteria within titles and abstracts. All terms were also used as MeSH terms where applicable. Test searches were run preceding the actual search in order to determine the right search terms. Additional File 1 shows the Medline search strategy in detail. The search was limited to English and German language publications.

Inclusion criteria

Abstracts were screened by two authors using the following inclusion criteria: (i) randomized controlled trials (RCT) or review articles (ii) of the adult (≥ 18 years) general population, (iii) evaluating interventional programmes including general practitioner training, mentioned in the abstract and (iv) reporting effects on depressive symptomatology. All extracted review articles were scanned and hand-searched for further relevant publications from 1999 onward.

Studies examining effects in specific study samples (such as diabetic patients with co-morbid depression) were excluded. Research of those specific samples was thought to provide only limited evidence for primary health care patients in general. All articles where a clear decision could not be made based on title or abstract were retrieved for a more detailed analysis. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted and then a consensus decision was achieved.

Training and education of general practitioners was defined as a professional intervention [21] that involves the use of guidelines or short training classes with a focus on optimising diagnosis as well as treatment. Studies involving additional organisational interventions were excluded. Additional file 2 gives an overview on excluded studies.

Data extraction

Primarily, methodical data on sampling, study design, intervention procedure, and outcome criteria were extracted from all selected studies. Extraction of results focussed on assessing symptom alteration primarily. Only data related to a change in symptom severity (scale scores, remission rates) were extracted. Effect sizes were only calculated for the outcomes considered as relevant (symptom change). Secondly, the selection criteria described in the above section were then reapplied to ensure accurate study inclusion.

Study Quality

Study quality was also assessed by two independent raters using a modified scale based on work by Moncrieff and colleagues [30]. The scale was modified by leaving out irrelevant items such as medication side-effects. It consists of 21 items leading to a maximum score of 42 points (Table 1). Each item, if not specified otherwise, was scored as 2 (fully met the quality criterion), 1 (partially met the quality criterion) or as 0 (did not meet the quality criterion). After a first independent run-through of ratings, the two raters met with a third independent researcher in order to discuss disagreements in scoring until a consensus was reached. Study protocols were consulted where possible.

Effect Size and meta-analysis

Whenever applicable, standardized mean effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated from the data reported. At times, studies only reported scores that could not be used in effect size calculation and efforts to retrieve data directly from the authors were made. Data was entered to interpret negative standardized means in favour of the intervention. Results of cluster trials were used when the authors accounted for the effect of cluster randomization properly. According to Cohen (1988), effect sizes of 0.2 are considered small, while d = 0.5 represents a moderate effect and d = 0.8 is regarded a large effect [31]. A meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager Software [32]. Due to the diversity of GP training in the studies, standardized mean effects were pooled - firstly, for studies with GP training only, secondly, for studies introducing additional guidelines and lastly for studies including more complex interventions. Subgroup analysis (patient inclusion, age of patients) were not carried out due to the unavailability of sufficient data. Analysis of the heterogeneity of prevalence across studies was done through I2 statistic and Cochran Q. A fixed effect model was applied since heterogeneity was low.

Results

Search results

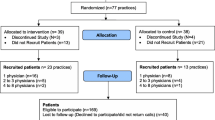

The results of the systematic literature search are shown in Figure 1. Interrater reliability showed substantial agreement (Kappa = 0.74). Overall, 108 potentially relevant articles were identified. After retrieving all full articles, 97 further articles were rejected as not fulfilling the selection criteria. Eleven articles were assessed and included for detailed analysis. Relevant study characteristics can be found in Table 2. Three articles are double publications of the same studies and will be subtracted for the following overview. The QuEST intervention is described in detail in a publication by Rost et al. (2000). Therefore, this reference will be used when referring to that study.

Study characteristics

All, but one, studies were conducted in anglophone countries, among them Great Britain (n = 4) and one study each in Canada, the United States and Australia. The sample sizes varied from 145 [33] to 733 [34, 35]. Three studies included patients with a categorical (e.g. diagnostic system based) diagnosis of depression [33, 36, 37], while the other five made use of symptom rating scales (self-report scales). Gask et al. (2004) and Worrall et al. (1999) both based their samples on referrals by the general practitioner (having the GP determine whether the patient was depressed) but applied dimensional instruments to ensure accuracy of diagnoses [38, 39]. All but one study used a cluster allocation design, randomising all included general practices to either intervention or control group. Only Llewellyn-Jones et al. (1999) conducted a serial designed survey, randomising each consecutive patient to the experimental groups [40]. Four research groups planned to train the control group practitioners after the end of the trial while the other four had them assigned to usual care groups with no further support provided. However, three study teams chose to provide the physicians of the control groups with depression specific guidelines [36, 39, 40]. In the Dutch study it is highlighted, that all practitioners are generally encouraged to adhere to guideline concordant treatment [33].

Interventions

As for interventional strategies, education and training of the participating general practitioners was the sole intervention in three studies [33, 38, 41]. These studies did not provide any other organisational support for the practices. King et al. (2002) pose an exception to the other studies, since physicians here are trained to provide a specific interventional method (brief cognitive behavioural therapy) [41], while in the remaining trial physicians were only provided with lectures on assessment and treatment of depression. Four studies made use of guideline implementation [35–37, 39]. These studies can be seen as providing a more intense intervention, as practitioners were trained and additionally received guidelines and guideline explanations. Rost et al. (2000) and Worrall et al. (1999) focussed the GP training on implementing guidelines [37, 39]. Thompson et al. (2000) also educated practitioners but additionally tried to implement guideline concordant treatment [35]. Baker et al. (2001) used a tailored application of practitioner training by firstly analysing possible obstacles for successful guidelines implementation and then delivering individualised help to the GPs [36].

Regarding more complex interventions, it can be concluded that provider education plays the central part in the programme conducted by Llewellyn-Jones et al. (1999).

The mean quality score of all studies was at 34.91 points and ranged from 26 to 39 (individual scores in table 2). Criteria such as random allocation as proposed by the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook were adequately addressed by all studies [42].

Effectiveness of provider training

Table 3 summarises all study results. The three studies solely providing physician education found no change in symptom severity. Neither lectures for more qualified assessment and treatment [33, 38], nor training in brief cognitive behavioural therapy [41] led to significant symptom change in patients of trained physicians. Introducing additional guidelines and using them during practitioner training, two studies showed a mid and long term significant change in symptom load [39, 43–45]. Both trials report small effect sizes (d = 0.22-0.29). Short term, one study was able to show an increases probability of reducing the depression score below a clinically relevant cut-point [36]. Yet, another study fails to show effects of the intervention introducing guidelines. Not only was there no effect of the practitioner training on diagnosis sensitivity and specificity, patient also do not profit symptom wise or regarding hospital admittance [34, 35].

As for the more complex interventional strategies, there is one study in which general practitioner and provider training plays a central role [40]. In a sample of elderly (65+) adults in a residential facility, Llewellyn-Jones and colleagues (1999) show a significant change in symptom quantity associated with a small effect size of Cohen's d = 0.17.

In studies that provided guidelines for the non-trained control group practitioners [36, 39, 40], additional training and interventions in the experimental groups led to positive outcome changes (see tables 2 and 3).

Meta-analysis

The forest-plot of the conducted meta-analysis can be found in Figure 2. Three studies with only provider training provided data for meta-analysis. They found a non-significant decrease in depressive symptom load (pooled effect size d=-0.07, 95% CI -0.24 to 0.10, I2 = 21%).

Two studies were categorized as implementing additional guidelines to primary care. They showed the highest pooled effect sizes and a significant decrease in depressive symptoms in the intervention groups (d=-0.26, 95% CI -0.48 to -0.04). The overall effect size, including a study with a more complex intervention was determined at d=-0.15 (95% CI -0.27 to -0.03]), favouring the experimental groups.

Discussion

It is apparent that there are only few trials evaluating the effect of primary care physician education on health outcomes of patients. Especially during the last six years no results of education based interventions have been published. It seems that the research focus has shifted to more complex interventions encompassing collaborative and stepped care approaches by introducing mental health specialists to the primary care setting [46–48]. Regarding the results of the reviewed studies, this approach seems more than justified - it has yet to be shown that training practitioners alone yields significant symptom changes; however, this conclusion is only based on three relevant studies that themselves are highly diverse. While the study by Gask et al. (2004) struggles with high attrition rates, King et al. (2002) used a rather high cut-off and included chronically depressed patients, possibly leading to a conservative bias and therefore underestimating the treatment effect [38, 41]. The authors argue that the applied kind of brief cognitive behavioural therapy might have been treatment approach not sufficiently intense for highly depressed patients. Bosmans et al. (2006) find that including less severely affected patients might have led to an underestimation of the efficacy of anti-depressant treatment [33].

Sample selection plays a major role in assessing treatment effects in general. One could assume that severely affected patients benefit more from treatment in clinical studies (as they can show a higher reduction in quantity of symptoms). In line with this, a categorical diagnostic approach for patient inclusion by applying diagnostic categories as provided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) might lead to a sample of more severely affected patients [33, 36, 37].

Furthermore, the kind of treatment has an effect. In the context of stepped care, this issue is addressed by providing more-intense treatment options to higher affected patients [25].

Both argumentations can provide explanations for the positive results found by studies implementing additional guideline usage by general practitioners. Small effect sizes were shown by those studies including patients with new-onset depression, rather than chronically depressed patients (as done by Kendrick et al., 2001 not resulting in positive symptom change). Obviously, the effect of mere attention to the trained practitioners as well as to the patients themselves (referred to as Hawthorne effect) has to be considered a possible moderating variable in study designs. This would lead to better outcomes and performances of the control groups even though they received no active intervention; thus, the differences found may possibly be even higher.

The justification for more complex interventions to improve primary care depression treatment is replicated in the analysis of included studies and basically goes in line with a previous review [21], however, we did find more evidence in newer studies that support guideline implementation to be effective in symptom reduction. One trial applying more complex strategies both yielded significant changes in symptom outcomes; however, it remains unclear how much of the effect can be attributed to the physicians' education. Bower et al. (2006) conducted a meta-regression to evaluate active ingredients of collaborative care interventions [49]. In this analysis, primary care physician training is not associated with a positive change in depressive symptoms nor with a change in antidepressant use even in univariate calculations. Rather than provider education, systematic identification of patients, professional background of staff and supervision proved to be significant predictors of symptom change. It becomes clear that researchers should not assume an additive effect of treatment modules; especially in view of economic considerations, collaborative care cannot mean implementing as many treatment options as possible. This analysis of one specific potentially effective part of collaborative care is leading the way to a more thorough understanding of complex interventions and has to be pursued without neglecting the fact that more simple interventions can also lead to significant changes in patient outcomes as shown in this review.

However, it may not be appropriate to solely focus on outcomes of symptomatology as enhanced primary care supply may not be directly associated with such. Even the included studies show a rise in adherence to medication treatment [39] and medication treatment in general [34, 44, 50]. It has been shown that effectiveness of antidepressant treatment increases with depression severity [51]; an effect of increased antidepressant treatment in a sample of mildly depressed patients will therefore be small [as seen in the studies by [33, 39]].

Strengths and Limitations

This review only included randomised controlled trials, and therefore neglected observational and non-randomised studies. RCTs often adhere to strict exclusion criteria, thus making generalisability to primary care patients difficult. This also applies to the current review since studies with specialised co-morbid patient groups were excluded; however, regarding the heterogeneity of primary care patients, an adequate representation of studies seems hard to achieve in any case. The reported studies differ substantially in content, duration, intensity and frequency of the intervention programmes, making comparisons difficult. However, we were able to conduct a meta-analysis, quantifying the results of the studies. Meta-regression that could help determine the influence of these factors was not applicable due to the limited number of studies.

This partly results from the relatively narrow search strategy; only when education or training efforts of GPs were mentioned within title and abstract, the article was found with the applied search strategy. Earlier publications (before 1999) were not searched. Gilbody et al. mention one previous trial that showed positive effects of provider training but equally emphasise methodological weakness of this trial [21, 52], so we did include relevant trials that live up to methodological requirements.".

Furthermore, a possible publication bias cannot be ruled out or determined with a qualitative review as this, especially under the regard of not searching grey literature. Regarding the fact that almost only studies from anglophone countries were found might be an indicator for unpublished studies with negative outcomes from other countries.

Conclusions

It seems that provider training, if combined with guideline implementation, contributes to enhanced care for depression in primary care even associated with possible positive symptom changes. Providing a guideline and training practitioners to adhere to guideline-concordant treatment might be a measure of intervention that endures even after the intervention ends.

References

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, de Girolamo G, Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, et al: Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004, 21-27.

Wittchen HU, Jacobi F: Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe--a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005, 15: 357-376. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.012.

Frei A, Ajdacic-Gross V, Rossler W, Eich-Hochli D: Effects of depressive disorders on objective life quality criteria. Psychiatr Prax. 2004, 31: 298-303. 10.1055/s-2003-814822.

Greer TL, Kurian BT, Trivedi MH: Defining and measuring functional recovery from depression. CNS Drugs. 2010, 24: 267-284. 10.2165/11530230-000000000-00000.

Cuijpers P, Smit F: Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies. J Affect Disord. 2002, 72: 227-236. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00413-X.

Luppa M, Heinrich S, Angermeyer MC, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG: Cost-of-illness studies of depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2007, 98: 29-43. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.017.

Gunther OH, Friemel S, Bernert S, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC, König HH: [The burden of depressive disorders in Germany - results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD)]. Psychiatr Prax. 2007, 34: 292-301.

Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Rupp AE, Schoenbaum M, Wang PS, Zaslavsky AM: Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008, 165: 703-711. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126.

König HH, Luppa M, Riedel-Heller SG: [The Costs of Depression and the Cost-Effectiveness of Treatment]. Psychiatr Prax. 2010, 37: 213-215. 10.1055/s-0030-1248510.

Halfin A: Depression: the benefits of early and appropriate treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2007, 13: S92-S97.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Improving quality of care for people with depression. Translating research into practice. Fact sheet. 2000, accessed 1-7-2011, [http://www.ahrq.gov/research/deprqoc.htm]

Wittchen HU, Holsboer F, Jacobi F: Met and unmet needs in the management of depressive disorder in the community and primary care: the size and breadth of the problem. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62 (Suppl 26): 23-28.

Bijl D, van Marwijk HW, Haan M, van Tilburg W, Beekman AJ: Effectiveness of disease management programmes for recognition, diagnosis and treatment of depression in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract. 2004, 10: 6-12. 10.3109/13814780409094220.

Dowrick C: Does testing for depression influence diagnosis or management by general practitioners?. Fam Pract. 1995, 12: 461-465. 10.1093/fampra/12.4.461.

Dowrick C, Buchan I: Twelve month outcome of depression in general practice: does detection or disclosure make a difference?. BMJ. 1995, 311: 1274-1276. 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1274.

Sielk M, Altiner A, Janssen B, Becker N, de Pilars MP, Abholz HH: [Prevalence and diagnosis of depression in primary care. A critical comparison between PHQ-9 and GPs' judgement]. Psychiatr Prax. 2009, 36: 169-174. 10.1055/s-0028-1090150.

Spitzer RL, Wakefield JC: DSM-IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: does it help solve the false positives problem?. Am J Psychiatry. 1999, 156: 1856-1864.

Prins MA, Verhaak PF, van der MK, Penninx BW, Bensing JM: Primary care patients with anxiety and depression: need for care from the patient's perspective. J Affect Disord. 2009, 119: 163-171. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.019.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for depression in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2009, 151: 784-792.

Gilbody S, House A, Sheldon T: Screening and case finding instruments for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005

Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R: Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003, 289: 3145-3151. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145.

Huibers MJH, Beurskens A, Bleijenberg G, van Schayck CP: Psychosocial interventions by general practitioners. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007

McNaughton JL: Brief interventions for depression in primary care: a systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2009, 55: 789-796.

Schlette S, Lisac M, Blum K: Integrated primary care in Germany: the road ahead. Int J Integr Care. 2009, 9: e14.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Depression in Adults. National Clinical Practice Guideline 90. 2009, London: NICE

Patten SB, Bilsker D, Goldner E: The evolving understanding of major depression epidemiology: implications for practice and policy. Can J Psychiatry. 2008, 53: 689-695.

Cape J, Whittington C, Bower P: What is the role of consultation-liaison psychiatry in the management of depression in primary care? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010, 32: 246-254. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.02.003.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Systematic Review. CDR's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 2009, accessed 1-7-2011, [http://www.yps-publishing.co.uk]

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009, 62: 1006-1012. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Moncrieff J, Churchill R, Drummond DC, McGuire H: Development of a quality assessment instrument for trials of treatments for depression and neurosis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2001, 10: 126-133. 10.1002/mpr.108.

Cohen JW: Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 1988, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Review Manager (RevMan). 2011, Copenhagen, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, (Version 5.1)

Bosmans J, De Bruijne M, Van Hout H, Van Marwijk H, Beekman A, Bouter L, Stalman W, Van Tulder M: Cost-Effectiveness of a Disease Management Program for Major Depression in Elderly Primary Care Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 1020-1026. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00555.x.

Kendrick T, Stevens L, Bryant A, Goddard J, Stevens A, Raftery J, Thompson C: Hampshire depression project: changes in the process of care and cost consequences. Br J Gen Pract. 2001, 51: 911-913.

Thompson C, Kinmonth AL, Stevens L, Peveler RC, Stevens A, Ostler KJ, Pickering RM, Baker NG, Henson A, Preece J, et al: Effects of a clinical-practice guideline and practice-based education on detection and outcome of depression in primary care: Hampshire Depression Project randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000, 355: 185-191. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03171-2.

Baker R, Reddish S, Robertson N, Hearnshaw H, Jones B: Randomised controlled trial of tailored strategies to implement guidelines for the management of patients with depression in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001, 51: 737-741.

Rost K, Nutting PA, Smith J, Werner JJ: Designing and implementing a primary care intervention trial to improve the quality and outcome of care for major depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000, 22: 66-77. 10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00059-1.

Gask L, Dowrick C, Dixon C, Sutton C, Perry R, Torgerson D, Usherwood T: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention for GPs in the assessment and management of depression. Psychol Med. 2004, 34: 63-72. 10.1017/S0033291703001065.

Worrall G, Angel J, Chaulk P, Clarke C, Robbins M: Effectiveness of an educational strategy to improve family physicians' detection and management of depression: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 1999, 161: 37-40.

Llewellyn-Jones RH, Baikie KA, Smithers H, Cohen J, Snowdon J, Tennant CC: Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999, 319: 676-682. 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.676.

King M, Davidson O, Taylor F, Haines A, Sharp D, Turner R: Effectiveness of teaching general practitioners skills in brief cognitive behaviour therapy to treat patients with depression: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002, 324: 947-950. 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.947.

Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2008, Chichester: Wiley

Pyne JM, Rost KM, Zhang M, Williams DK, Smith J, Fortney J: Cost-effectiveness of a primary care depression intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2003, 18: 432-441. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20611.x.

Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Werner J, Duan N: Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention. Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16: 143-149. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00537.x.

Rost K, Pyne JM, Dickinson LM, LoSasso AT: Cost-effectiveness of enhancing primary care depression management on an ongoing basis. Ann Fam Med. 2005, 3: 7-14. 10.1370/afm.256.

Bower PJ, Rowland N: Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of counselling in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006

Skultety KM, Zeiss A: The treatment of depression in older adults in the primary care setting: an evidence-based review. Health Psychol. 2006, 25: 665-674.

Skultety KM, Rodriguez RL: Treating geriatric depression in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008, 10: 44-50. 10.1007/s11920-008-0009-2.

Bower PJ, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A: Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006, 189: 484-493. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023655.

Roskar S, Podlesek A, Zorko M, Tavcar R, Dernovsek MZ, Groleger U, Mirjanic M, Konec N, Janet E, Marusic A: Effects of training program on recognition and management of depression and suicide risk evaluation for Slovenian primary-care physicians: follow-up study. Croat Med J. 2010, 51: 237-242. 10.3325/cmj.2010.51.237.

Fournier JC, Derubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J: Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010, 303: 47-53. 10.1001/jama.2009.1943.

Rutz W, von Knorring L, Walinder J: Frequency of suicide on Gotland after systematic postgraduate education of general practitioners. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989, 80: 151-154. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb01318.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/10/prepub

Acknowledgement and funding

This work is part of Esther-Net and was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research [grant number: 01ET0719 (Esther-Net)]. The German Federal Ministry for Education and Research had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analyses and interpretation of data; in writing the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The publication of study results was not contingent on the sponsor's approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CS, ML and SRH outlined and specified the research questions. The principal author and ML conducted the literature search and screened abstracts and titles. Article inclusion and study quality was also evaluated by ML and SRH. CS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HHK and HvdB revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sikorski, C., Luppa, M., König, HH. et al. Does GP training in depression care affect patient outcome? - A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 12, 10 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-10