Abstract

Background

Over 60 implementation frameworks exist. Using multiple frameworks may help researchers to address multiple study purposes, levels, and degrees of theoretical heritage and operationalizability; however, using multiple frameworks may result in unnecessary complexity and redundancy if doing so does not address study needs. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) are both well-operationalized, multi-level implementation determinant frameworks derived from theory. As such, the rationale for using the frameworks in combination (i.e., CFIR + TDF) is unclear. The objective of this systematic review was to elucidate the rationale for using CFIR + TDF by (1) describing studies that have used CFIR + TDF, (2) how they used CFIR + TDF, and (2) their stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF.

Methods

We undertook a systematic review to identify studies that mentioned both the CFIR and the TDF, were written in English, were peer-reviewed, and reported either a protocol or results of an empirical study in MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycInfo, Web of Science, or Google Scholar. We then abstracted data into a matrix and analyzed it qualitatively, identifying salient themes.

Findings

We identified five protocols and seven completed studies that used CFIR + TDF. CFIR + TDF was applied to studies in several countries, to a range of healthcare interventions, and at multiple intervention phases; used many designs, methods, and units of analysis; and assessed a variety of outcomes. Three studies indicated that using CFIR + TDF addressed multiple study purposes. Six studies indicated that using CFIR + TDF addressed multiple conceptual levels. Four studies did not explicitly state their rationale for using CFIR + TDF.

Conclusions

Differences in the purposes that authors of the CFIR (e.g., comprehensive set of implementation determinants) and the TDF (e.g., intervention development) propose help to justify the use of CFIR + TDF. Given that the CFIR and the TDF are both multi-level frameworks, the rationale that using CFIR + TDF is needed to address multiple conceptual levels may reflect potentially misleading conventional wisdom. On the other hand, using CFIR + TDF may more fully define the multi-level nature of implementation. To avoid concerns about unnecessary complexity and redundancy, scholars who use CFIR + TDF and combinations of other frameworks should specify how the frameworks contribute to their study.

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42015027615

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Scholars seeking to study innovation implementation in healthcare have over 60 conceptual frameworks to guide their work [1]. Frameworks can guide implementation, facilitate the identification of determinants of implementation, guide the selection of implementation strategies, and inform all phases of research by helping to frame study questions and hypotheses, anchor background literature, clarify constructs to be measured, depict relationships to be tested, and contextualize results [2, 3]. Frameworks provide a common language, allowing for cumulative evidence to develop.

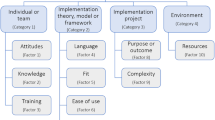

Implementation frameworks may differ from one another in a number of ways. First, they may serve different purposes: to describe/guide the implementation process as a whole (e.g., the Knowledge to Action framework [4]), to identify determinants of implementation (e.g., the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR [5]), the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF [6])), or to evaluate implementation (e.g., Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance [7]). Second, implementation frameworks differ in the conceptual level at which they focus, with some focused on a single level (e.g., organizational, team, individual) and others being multi-level [1, 8]. Third, they differ in their degree of theoretical heritage, ranging from emergent, context-specific conceptual frameworks to theoretical frameworks that describe and/or combine explanations derived from multiple evidence-based theories (e.g., the exploration, adoption decision/preparation, active implementation, sustainment framework). Fourth, they may differ in their degree of operationalizability, with some including definitions, tools, and suggested methodological approaches to facilitate use and promote consistent application [1]. For example, the CFIR has an online technical assistance website (www.cfirguide.org) with sample interview questions that tap included specific constructs, and Michie et al. (2005), which introduces the TDF, contains sample interview questions for each TDF domain as well as a recently developed quantitative questionnaire [6, 9]. Atkins et al. have a manual for TDF application currently under review for publication (personal communication, Lou Atkins, November 15, 2016).

A key challenge for researchers and practitioners is how to select from among the growing number of frameworks [10]. In many cases, a single framework can be used to address study needs. In some cases, scholars may use multiple frameworks because a single framework cannot comprehensively address study needs. Scholars may need to use multiple frameworks to address multiple study purposes (e.g., to identify determinants and inform evaluation) or conceptual levels (i.e., multi-level studies), to account for multiple theoretical perspectives, or to adequately operationalize key concepts. In contrast, if a single framework is sufficient for addressing study needs, using multiple frameworks may threaten the scientific principle of parsimony, potentially resulting in unnecessary complexity and redundancy, particularly if each included framework does not contribute some unique content (e.g., purpose, conceptual level, theoretical perspective, operationalization).

To avoid concerns that using multiple frameworks introduces unnecessary complexity and redundancy, scholars should provide a clear rationale for using multiple frameworks. Analyzing studies that use both the CFIR and the TDF (hereafter, CFIR + TDF) may be instructive for understanding scholars’ rationales for using multiple frameworks because of these frameworks’ apparent similarities: The CFIR and the TDF are both well-operationalized, multi-level implementation determinant frameworks derived from theory. The CFIR includes 39 constructs (i.e., discrete theoretical concepts) arranged across five domains (i.e., groups of conceptually related constructs), emphasizing determinants of implementation that may be active primarily, though not exclusively, at the collective (e.g., organization) level. Domains include intervention characteristics (e.g., adaptability), outer setting (e.g., patient needs and resources), inner setting (e.g., culture), and process (e.g., planning). One domain, characteristics of individuals, focuses on individual-level constructs (e.g., self-efficacy). The CFIR has been applied to a diverse array of studies that have investigated mental health workers’ views of a health self-management program, identified determinants of successful implementation of evidence-based practices in public health agencies, designed a tailored intervention strategy to improve hospital services for children, and evaluated success of an implementation trial to improve uptake of a re-engagement program for patients with mental illness in Veterans Affairs medical centers, among others [11].

The TDF is another commonly used implementation determinant framework that includes 128 constructs in 12 domains derived from 33 theories of behavior change [6]. The TDF provides a high level of elaboration for constructs related to individual level change though it also includes collective (e.g., organization) level constructs [12]. TDF domains include knowledge (e.g., of scientific rationale for implementation); skills (e.g., ability); social/professional role and identity (e.g., group norms); beliefs about capabilities (e.g., self-efficacy); beliefs about consequences (e.g., outcome expectancies); motivation and goals (e.g., intention); memory, attention, and decision processes (e.g., attention control); environmental context and resources (e.g., resources); social influences (e.g., leadership); emotion (e.g., burnout); behavioral regulation (e.g., feedback); and nature of the behavior (e.g., routine). The TDF has also been applied in numerous studies, including process evaluation of a Canadian CT head rule trial, a qualitative study of factors influencing mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department, barriers and facilitators of interventions to engage pregnant women in smoking cessation, and investigation of perceptions about pre-operative testing in low-risk patients [13–16].

We are aware of (and, in the case of BP, FL, NG, and JF, have authored) studies that have used CFIR + TDF; however, given the apparent similarities between the CFIR and the TDF in terms of purpose, level, degree of theoretical heritage, and operationalizability, the rationale for using CFIR + TDF is not readily apparent. The objective of this study is to elucidate the rationale for using CFIR + TDF. To achieve this objective, we describe (1) published studies that have used CFIR + TDF, (2) how they used CFIR + TDF (e.g., to address multiple study purposes or conceptual levels), and (3) their stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF. In fulfilling this objective, we aim to inform the judicious use of CFIR + TDF and combinations of other frameworks in future implementation studies. When necessary, using multiple frameworks to address study needs may help to limit the proliferation of frameworks and the related fragmentation of knowledge by ensuring that existing frameworks continue to be used, evaluated, and refined and by avoiding segmentation of the field through the use of a single preferred framework over another [1, 17, 18]. Using multiple frameworks may curtail “pseudoinnovation,” wherein perceived advances in framework development are more aptly characterized as reinvention rather than true innovation [18]. In addition, studies that use multiple frameworks may yield more practically relevant results, particularly if the frameworks selected can help to conceptualize implementation at multiple levels [8, 19]. Perhaps equally important, the use of multiple frameworks may represent an opportunity to move implementation science toward greater interdisciplinarity.

Methods

Our systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and checklist (Additional file 1), using the accompanying explanation and elaboration document. The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on November 3, 2015 and updated on December 12, 2016 (registration number CRD42015027615).

Search strategy

To identify studies that used CFIR + TDF, we searched for published articles that referred to both the “Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research” (or “CFIR”) and the “Theoretical Domains Framework” (or “TDF”) in the full text in the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The TDF was published in the 2005 article “Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach” (Michie et al. 2005 [6]), but it was not named as the Theoretical Domains Framework until 2012 [12]. To capture records that used the CFIR and referenced Michie et al. (2005) [6], possibly representing the use of both the CFIR and the TDF before it was named as such, we also searched PsycInfo, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for records that referred to both the “Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research” (or “CFIR”) and “Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach [6].” (We did not search PubMed because it does not search references.) We conducted these searches first in December 2015 and again in October 2016.

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the study, records were required to mention both the CFIR and the TDF, be written in the English language and peer-reviewed, and report either a protocol for or results of an empirical study.

Study selection process

SB, AK, and YY selected records for inclusion in the study. These authors conducted title, abstract, and full-text review, searching for evidence of CFIR + TDF use. Discrepancies were resolved through discussions between the three authors and, when necessary, BP until consensus was reached. During this process, 65 records were excluded because they did not report empirical research, were not published in English, or did not use both frameworks. SB and either AK or YY then reviewed full text of the remaining 12 records, confirming evidence of CFIR + TDF use in each record.

Data extraction and analysis

Given our a priori interest in understanding why and how CFIR + TDF has been used, we used a framework analysis approach [20]. In general, the framework analysis approach allows researchers to analyze qualitative data in a matrix format (i.e., Excel workbook) consisting of rows (cases), columns (codes), and cells (summarized data [21]). We adopted a framework analysis approach that included five key phases: familiarization, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping and interpretation. First, in the familiarization phase, we reviewed included studies and familiarized ourselves with the literature base. Second, we identified a thematic framework based on our specific research objectives. This thematic framework served as the columns (codes) for data abstraction. To describe studies to which researchers have applied CFIR + TDF, our thematic framework included study objective, design, setting, unit of analysis, and outcomes assessed. Consistent with our study objectives, our thematic framework also included authors’ stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF and how CFIR + TDF was used (i.e., explicit rationale for using CFIR + TDF, specifically, related to one or more of the dimensions listed in Table 2 or another dimension that authors identified as a rationale for using CFIR + TDF). Next, in the indexing and charting phases, we abstracted text selections from included articles and placed them into the appropriate cells within our framework. Indexing and charting of all included articles was completed by two authors (SB, AK). All discrepancies in the indexing and charting phase were discussed until consensus was reached. Finally, in the mapping and interpretation phase, summarized data from each cell were analyzed to address each research question ((1) what studies have used CFIR + TDF, (2) how they used CFIR + TDF (e.g., framing, data collection, analysis), and (3) their stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF). Themes related to each research question were discussed among SB, BP, and AK until consensus was reached.

Results

Our search yielded 95 publications. We removed 18 duplicates, leaving 77 for screening; of these, we excluded 65 publications because they did not mention both the CFIR and the TDF, were not written in English, or did not report a protocol or results of empirical studies (see Fig. 1). We identified 12 CFIR + TDF articles; the final list of included studies comprised five protocols for empirical studies (Gould [22], Prior [23], Manca [24], Graham-Rowe [25], Sales [26]) and seven completed empirical studies (Murphy [27], English [28], Bunger [29], Moullin [30], Newlands [31], Templeton [32], Elouafkaoui [33]).

Description of studies that have used CFIR + TDF

Table 1 displays characteristics of included studies: objective, setting, intervention phase (i.e., design, feasibility/piloting, implementation, and evaluation), design, methods, data sources, unit of analysis, and outcomes assessed. Throughout the description of studies that have used CFIR + TDF that follows, we incorporate descriptions of how the studies used CFIR + TDF.

Objective

All studies’ objectives were related to interventions to improve health care. Two completed studies and two protocols described intervention design and/or implementation plans (Gould [22], Sales [26], Murphy [27], English [28]); one protocol described a comparison of the effectiveness of an intervention relative to standard care (Prior [23]), and two protocols and five completed studies evaluated interventions (Manca [24], Sales [26], Bunger [29], Moullin [30], Newlands [31], Templeton [32], Elouafkaoui [33]). Several of the included studies had multiple objectives (e.g., effectiveness study and concurrent qualitative process evaluation [23, 33]).

Setting

All study settings were healthcare organizations. Two were hospitals (Gould [22], English [28]). Other settings included pharmacy, dentistry, primary care, and behavioral health agencies. Studies were conducted in Australia (1), Canada (2), England (1), Kenya (1), Scotland (4), and the USA (2).

Intervention phase

In the included studies, CFIR + TDF was applied across all phases of an intervention (i.e., design, feasibility/piloting, implementation, and evaluation; see Table 1). Two completed studies and two protocols (Gould [22], Sales [26], Murphy [27], English [28]) used the frameworks in the intervention design phase. One of these protocols (Gould [22]) also planned to apply CFIR + TDF in the feasibility/piloting phase to identify current practice of healthcare professionals within the intervention target healthcare setting and identify barriers and facilitators to performing the target behavior. The other protocol (Sales [26]) also planned to apply CFIR + TDF in the implementation phase. Another protocol (Prior [23]) was focused only on the implementation phase, proposing to use CFIR + TDF to assess acceptability of the intervention and identify barriers and facilitators to the intervention target behavior. Ostensibly, protocols may yield future intervention development papers and results papers that apply CFIR + TDF to additional intervention phases. Five completed studies and two protocols applied CFIR + TDF to the intervention evaluation phase (Manca [24], Graham-Rowe [25], Bunger [29], Moullin [30], Newlands [31], Templeton [32]).

Design

Nine of the 12 completed studies and protocols had observational designs; one protocol and one completed study were randomized controlled trials that incorporated a process evaluation (Prior [23], Elouafkaoui [33]). One protocol was a systematic review (Graham-Rowe [25]).

Methods

Two studies’ (Murphy [27], English [28]) sole objective was intervention design, using environmental scans, a priori knowledge about context, and a theory-informed approach. One study was quantitative (Bunger [29]), and two completed studies and four protocols were mixed-method (Gould [22], Prior [23], Manca [24], Sales [26], Templeton [32], Elouafkaoui [33]) including interviews, questionnaires, observation, comparative effectiveness, framework analysis, and network analysis. (Note that Gould et al. used CFIR + TDF in only one of their three sub-studies in which only qualitative (interview and observation) methods were used [22].) Two studies were qualitative (Moullin [30], Newlands [31]), and one protocol was a systematic literature review (Graham-Rowe [25]).

Data collection

Two completed studies (Murphy [27], English [28]) designed interventions; their data sources included results from authors’ previous and ongoing research (Murphy [27], English [28]), the published literature (Murphy [27], English [28]), authors’ cumulative tacit knowledge and experience (Murphy [27], English [28]), and informal discussions with stakeholders (English [28]); notably, both intervention development studies’ authors described CFIR + TDF as data sources. A third completed study (Bunger [29]) applied neither the CFIR nor the TDF during data collection. One protocol (Manca [24]) and one completed study (Moullin [30]) planned to collect qualitative interview data but did not state how CFIR + TDF would be used during data collection. Three protocols and two completed studies (Gould [22], Prior [23], Sales [26], Newlands [31], Elouafkaoui [33]) developed or planned to develop (Sales [26]) interview topic guides using CFIR + TDF, and one completed study developed a provider questionnaire using CFIR + TDF (Templeton [32]); however, none fully specified which constructs or domains would be used or how constructs or domains would be selected. One protocol, the systematic review (Graham-Rowe [25]) indicated that the authors would include some terms related to TDF domains in their search strategy, but they did not specify TDF domains.

Data analysis

Two completed intervention studies (Murphy [27], English [28]) indicated that they used CFIR + TDF not explicitly for data analysis but rather to promote their intervention’s implementation. English et al. indicated that they primarily used CFIR’s intervention domain, considering its constructs in the design and packaging of their intervention; they identified the TDF’s skills, social/professional role identity, reinforcement, goal, and social influence constructs as particularly relevant for informing the design of their intervention [28]. Murphy et al. used CFIR + TDF to “consciously give priority to the process of implementation within the design of the intervention” [27]. Specifically, the CFIR offered them a “meta-view” of constructs to consider that were relevant to the implementation of their intervention. How Murphy et al. used the TDF in data analysis was less clear, although the authors indicated that they considered the TDF during their assessment of pharmacists’ capability, opportunity, motivation, and behavior (COM-B) related to the intervention [27].

Two protocols (Gould [22], Prior [23]) and one completed study (Elouafkaoui [33]) were explicit in stating that CFIR + TDF would be (Gould [22])/was (Prior [23], Elouafkaoui [33]) used to code interview data, but none of these identified specific constructs or domains from each framework that would be used for analysis. Two studies used the TDF (not CFIR) to code interview data (Newlands [31], Templeton [32]). Moullin et al. used an adapted version of the CFIR, augmented with elements of the TDF, in a secondary analysis of interview data [30]. Graham-Rowe et al. planned to use all domains of CFIR + TDF to code data abstracted from their systematic review of existing literature [25]. Bunger et al. stated that CFIR + TDF provided theoretical justification for components of the learning collaborative intervention that they described, identifying specific constructs and domains from each framework that related to intervention components [29]. As with their explanation of how CFIR + TDF would inform data collection, two protocols were not explicit in stating whether and how CFIR + TDF would be used during data analysis (Manca [24], Sales [26]).

Unit of analysis

One protocol’s and one completed study’s units of analysis were the individual (Manca [24], Newlands [31]), and two protocols’ and one completed study’s units of analysis were the organization (Gould [22], Prior [23], Elouafkaoui [33]). Three completed studies and two protocols analyzed data at both individual and organizational levels (Graham-Rowe [25], Sales [26], Bunger [29], Moullin [30], Templeton [32]). As noted above, two completed studies’ sole objective was intervention design; although the intervention was targeted at healthcare professionals, environmental scan efforts were conducted in both studies, focusing on the societal, organizational, and individual levels (Murphy [27], English [28]). Five studies (Gould [22], Prior [23], Murphy [27], Templeton [32], Elouafkaoui [33]) and two protocols (Graham-Rowe [25], Sales [26]) referred to CFIR + TDF’s ability to tap the multiple levels at which implementation determinants lie, generally suggesting that the TDF tapped individual levels and the CFIR tapped collective levels.

Outcomes assessed. In contrast to other study characteristics, we only report outcomes assessed for study objectives that used CFIR + TDF. One completed study assessed healthcare professionals’ behavior (i.e., engagement in professional networks (Bunger [29]); two protocols assessed specific beliefs relating to a behavior (e.g., response to feedback from blood transfusion audit and feedback; Gould [22], Prior [23]); two protocols assessed intervention reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (Manca [24], Sales [26]); and three protocols and three studies assessed determinants of implementation (e.g., acceptability of the intervention; Gould [22], Prior [23], Moullin [30], Newlands [31], Templeton [32]). One study assessed the role and importance of CFIR + TDF domains (Graham-Rowe [25]). Two completed studies did not assess outcomes, as their sole objective was intervention design (Murphy [27], English [28]).

Stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF

Table 2 excerpts studies’ descriptions of their use of CFIR + TDF and, in most cases, their stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF; four studies did not explicitly state their rationale for using CFIR + TDF (English [28], Bunger [29], Newlands [31], Elouafkaoui [33]).

Of the eight studies that explicitly stated their rationale for using CFIR + TDF, three indicated that the CFIR and the TDF addressed different purposes (Prior [23], Manca [24], Murphy [27]). In each of the three studies, the authors described one framework as offering an overarching perspective on implementation determinants and the other as more conducive to translating findings into practical approaches to implementation. Interestingly, two of these studies (Prior [23] and Murphy [27]) described the CFIR as offering an overarching perspective on implementation determinants and the TDF as offering specific determinants of healthcare providers’ behavior, whereas the third study (Manca [24]) offered the opposite rationale, citing the TDF as including “all of the important constructs of implementation” and the CFIR as a framework that would assist in “identifying key elements in the program implementation in a systematic way.”

Six of the included studies that explicitly stated their rationale for using CFIR + TDF indicated that the CFIR and the TDF addressed different conceptual levels (Gould [22], Prior [23], Graham-Rowe [25], Sales [26], Moullin [30], Templeton [32]). In each of the studies that cited multiple conceptual levels as their rationale for using CFIR + TDF, authors suggested that the CFIR addressed the collective level and the TDF addressed the individual level. For example, Sales et al. wrote “Our primary rationale for using both frameworks is that one (TDF) specializes in individual-level behavior change, while the other (CFIR) focuses more on the organizational level, above the individual” [26].

None of the studies’ rationales for using CFIR + TDF related to accounting for multiple theoretical perspectives or adequately operationalizing key constructs.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to elucidate scholars’ rationale for using CFIR + TDF by describing (1) studies that have used CFIR + TDF; (2) how they used CFIR + TDF (e.g., framing, data collection, analysis); and (3) their stated rationale for using CFIR + TDF. CFIR + TDF was applied to studies in several countries, of a range of healthcare interventions and at multiple intervention phases. In particular, several of the included studies used CFIR + TDF to describe context by assessing characteristics of individuals and of the organization within which they were embedded. They then used this information to design tailored strategies for implementing an evidence-based practice. This reflects the generally held belief that tailoring strategies to context will lead to more effective implementation [34–36]. CFIR + TDF was also applied to studies with a variety of designs and methods, with multiple units of analysis and outcomes assessed.

Eight of the 12 studies included in our analysis explicitly stated a rationale for using CFIR + TDF. Three studies (Prior [23], Manca [24], Murphy [27]) suggested that the CFIR and the TDF addressed multiple study purposes. Authors of both the CFIR and the TDF describe the respective frameworks as a set of determinants to facilitate understanding implementation. In addition, Damschroder et al. suggested that the CFIR was intended to promote theory development and facilitate synthesis of research findings across studies and contexts [5], and Michie et al. suggested that the TDF may be used to promote the development of interventions to enhance implementation [6].

Differences in the purposes that authors of the CFIR and the TDF propose help to justify the rationale that these frameworks address multiple study purposes. Murphy et al. suggested that as a comprehensive framework, the CFIR provided a “meta-view” of implementation, whereas the TDF helped to conceptualize behavior change interventions [27]. Prior et al. similarly conceived of the CFIR as an “over-arching typology” for understanding implementation and the TDF as a lens for understanding provider behavior [23]. Manca et al. viewed the TDF as a comprehensive framework for understanding implementation but used the CFIR to inform the implementation process (a CFIR domain) [24].

Six studies (Gould [22], Prior [23], Graham-Rowe [25], Sales [26], Moullin [30], Templeton [32]) suggested that the TDF and the CFIR addressed different conceptual levels of implementation determinants. Damschroder et al. characterized the CFIR as a “comprehensive taxonomy of specific constructs related to the intervention, inner and outer setting, individuals, and implementation process” [5]. The TDF also includes constructs at multiple levels, including the individual and collective [6]. Given that the CFIR and the TDF both include determinants at both the individual and collective levels, the dichotomy that these six studies suggest may reflect potentially misleading conventional wisdom. To the extent that the CFIR and the TDF each sufficiently address constructs at the individual and collective levels, studies that use CFIR + TDF to address multiple conceptual levels may introduce unnecessary complexity and redundancy. On the other hand, it is possible that the CFIR and the TDF, when combined, help to more fully define the multi-level nature of behavior change in healthcare organizations than either of these frameworks alone. Formal efforts to map the CFIR and the TDF onto one another may help to explicate the extent to which using CFIR + TDF in fact helps to address multiple conceptual levels, or if using CFIR + TDF introduces unnecessary complexity and redundancy.

Four of the studies included in our analyses did not explicitly state a rationale for using CFIR + TDF; however, in some cases, how these studies used CFIR + TDF offered insight into their authors’ rationales for doing so. English et al. indicated that they primarily used the CFIR’s intervention domain and the TDF’s skills, social/professional role and identity, reinforcement, goals, and social influences constructs. The selection of these domains and constructs may suggest that English et al., like six other included studies, viewed the CFIR as a representative of the collective level and the TDF as a representative of the individual level: The CFIR’s intervention domain lies at the collective level, whereas the TDF constructs that English et al. included, such social/professional role and identity lie at the individual level. Similarly, Newlands et al. used the CFIR to collect data regarding the intervention (collective level) and the TDF to collect data regarding provider behavior (individual level), and in Elouafkaoui et al.’s [33] description of their unit of analysis, they suggested that TDF tapped individual levels and the CFIR tapped collective levels.

Our finding that several included studies did not explicitly state a rationale for using CFIR + TDF is consistent with other studies that have found inadequate descriptions and justifications for included frameworks in empirical studies [11, 37–39]. This underscores the need for guidance on how to apply frameworks and report their use, perhaps signaling the need for specific reporting standards such as those developed for implementation strategies [38, 40].

Implications

In fulfilling our objective of elucidating scholars’ rationale for using CFIR + TDF, we aimed to inform the judicious use of CFIR + TDF and combinations of other frameworks in future implementation studies. Doing so may help to limit the proliferation of frameworks and the related fragmentation of knowledge by ensuring that existing frameworks continue to be used, evaluated, and refined and by avoiding segmentation of the field through use of a single preferred framework over another [1, 17, 18]; curtail “pseudoinnovation,” wherein perceived advances in framework development are more aptly characterized as reinvention rather than true innovation [18]; yield more practically relevant study results; and move implementation science toward greater interdisciplinarity.

We found that eight of the 12 included studies indicated that they used CFIR + TDF to address multiple study purposes and conceptual levels. Specifically, authors of six included studies suggested that either the CFIR or the TDF offered an overarching perspective on implementation determinants, whereas the other was described as more conducive to translating findings into practical approaches to implementation. And authors of six included studies suggested that the CFIR and the TDF addressed distinct conceptual levels; generally speaking, these studies argued that the TDF addressed multiple conceptual levels but did not sufficiently elaborate on determinants of implementation at the collective level. To avoid concerns regarding unnecessary complexity or redundancy, scholars who use CFIR + TDF and combinations of other frameworks as useful for addressing multiple study needs should explicitly specify the benefits of each included framework; doing so will help to justify the use of multiple frameworks, and it will contribute to our understanding of each framework, its scope, and its limitations.

Our finding that some included studies did not explicitly state a rationale for using CFIR + TDF suggests that, at a minimum, future studies that apply multiple frameworks should clearly describe the ways in the frameworks, when combined, contribute to their study; the ways in which each framework alone is limited in contributing to their study; how the frameworks’ contributions converge and/or diverge; and recommendations for the refinement of one or more framework. Doing so will strengthen the studies and contribute generalizable knowledge regarding the frameworks.

Limitations

A few limitations of this systematic review should be noted. Although we searched many databases with wide coverage using clear, specific, and appropriate terms, we included only peer-reviewed published research in English. It is possible that the search did not yield all published studies that used CFIR + TDF. For example, additional applications may be found in “grey literature” or in different languages. In addition, our ability to understand scholars’ rationale for CFIR + TDF was limited to the extent that they did not explicitly state their rationale; however, how scholars used CFIR + TDF offered insight into their rationale. A future study that interviews scholars regarding their rationale for using CFIR + TDF may provide additional insight.

Conclusions

The findings from this review indicate that it is not uncommon for implementation researchers to use CFIR + TDF to inform their work. As future studies use CFIR + TDF and combine other frameworks, there is a need to answer fundamental questions about whether and how the use of multiple frameworks yields substantial benefits beyond that of a single framework applied to its full potential. This review also echoes findings from across the field of implementation science that the explicit use of theories and frameworks needs improvement [39]. Given the lack of guidance in the field, we call for the development of practical tools to guide the application of theories and frameworks as well as corresponding reporting guidelines. These efforts will help to clarify the application and contribution of theories and frameworks in implementation research and will facilitate richer theoretical understanding of implementation determinants, processes, and outcomes.

Abbreviations

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CFIR + TDF:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and Theoretical Domains Framework

- PROSPERO:

-

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

References

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–50.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, Baumann AA, Hamilton AM, Santens RL. Writing implementation research grant proposals: ten key ingredients. Implement Sci. 2012;7:96.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:26–33.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

Foy R, Ovretveit J, Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Taylor SL, Dy S, Hempel S, McDonald KM, Rubenstein LV, Wachter RM. The role of theory in research to develop and evaluate the implementation of patient safety practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:453–9.

Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Crone MR, Dusseldorp E, Presseau J. Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implement Sci. 2014;9:11.

Birken SA, Powell BJ, J P. Toward criteria for selecting appropriate frameworks and theories in implementation research. Poster session presented at: 8th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation; 2015 December 14–15; Washington, DC.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2016;11:72.

Francis JJ, O’Connor D, Curran J. Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:35.

Beenstock J, Sniehotta FF, White M, Bell R, Milne EM, Araujo-Soares V. What helps and hinders midwives in engaging with pregnant women about stopping smoking? A cross-sectional survey of perceived implementation difficulties among midwives in the North East of England. Implement Sci. 2012;7:36.

Curran JA, Brehaut J, Patey AM, Osmond M, Stiell I, Grimshaw JM. Understanding the Canadian adult CT head rule trial: use of the theoretical domains framework for process evaluation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:25.

Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci. 2012;7:52.

Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Gruen RL, Green SE, Knott J, Francis JJ, Michie S, O’Connor DA. Understanding practice: the factors that influence management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department—a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:8.

Noar SM, Zimmerman RS. Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ Res. 2005;20:275–90.

Walshe K. Pseudoinnovation: the development and spread of healthcare quality improvement methodologies. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21:153–9.

Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79:281–315.

Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, Ormston R. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2013.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117.

Gould NJ, Lorencatto F, Stanworth SJ, Michie S, Prior ME, Glidewell L, Grimshaw JM, Francis JJ. Application of theory to enhance audit and feedback interventions to increase the uptake of evidence-based transfusion practice: an intervention development protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:92.

Prior M, Elouafkaoui P, Elders A, Young L, Duncan EM, Newlands R, Clarkson JE, Ramsay CR. Evaluating an audit and feedback intervention for reducing antibiotic prescribing behaviour in general dental practice (the RAPiD trial): a partial factorial cluster randomised trial protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:50.

Manca DP, Aubrey-Bassler K, Kandola K, Aguilar C, Campbell-Scherer D, Sopcak N, O’Brien MA, Meaney C, Faria V, Baxter J, et al. Implementing and evaluating a program to facilitate chronic disease prevention and screening in primary care: a mixed methods program evaluation. Implement Sci. 2014;9:135.

Graham-Rowe E, Lorencatto F, Lawrenson JG, Burr J, Grimshaw JM, Ivers NM, Peto T, Bunce C, Francis JJ, For the WIDeR-EyeS Project team. Barriers and enablers to diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2016;5:134.

Sales AE, Ersek M, Intrator OK, Levy C, Carpenter JG, Hogikyan R, Kales HC, Landis-Lewis Z, Olsan T, Miller SC, Montagnini M, Periyakoil VS, Reder S. Implementing goals of care conversations with veterans in VA long-term care setting: a mixed methods protocol. Implement Sci. 2016;11:132.

Murphy AL, Gardner DM, Kutcher SP, Martin-Misener R. A theory-informed approach to mental health care capacity building for pharmacists. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8:46.

English M. Designing a theory-informed, contextually appropriate intervention strategy to improve delivery of paediatric services in Kenyan hospitals. Implement Sci. 2013;8:39.

Bunger AC, Hanson RF, Doogan NJ, Powell BJ, Cao Y, Dunn J. Can learning collaboratives support implementation by rewiring professional networks? Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:79–92.

Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernandez D, Benrimoj SI. Qualitative study on the implementation of professional pharmacy services in Australian community pharmacies using framework analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:439.

Newlands R, Duncan EM, Prior M, Elouafkaoui P, Elders A, Young L, Clarkson JE, Ramsay CR, for the Translation Research in a Dental Setting (TRiaDS) Research Methodology Group. Barriers and facilitators of evidence-based management of patients with bacterial infections among general dental practitioners: a theory-informed interview study. Implement Sci. 2016;11:11.

Templeton AR, Young L, Bish A, Gnich W, Cassie H, Treweek S, Bonetti D, Stirling D, Macpherson L, McCann S, Clarkson J, Ramsay C, With the PMC study team. Patient-, organization-, and system-level barriers and facilitators to preventive oral health care: a convergent mixed-methods study in primary dental care. Implement Sci. 2016;11:5.

Elouafkaoui P, Young L, Newlands R, Duncan EM, Elders A, Clarkson JE, Ramsay CR, Translation Research in a Dental Setting (TRiaDS) Research Methodology Group. An audit and feedback intervention for reducing antibiotic prescribing in general dental practice: the RAPiD cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13:8.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N, Wensing M, Fiander M, Eccles MP, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:Cd005470. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Signe_Flottorp/publication/275660974_Tailored_interventions_to_address_determinants_of_practice/links/55643ac608ae6f4dcc98d8f9.pdf. Issue #4.

Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Mandell DS. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2015. doi:10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6.

Wensing M, Bosch M, Grol R. Selecting, tailoring and implementing knowledge translation interventions. In: Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.; 2009. p. 94–113.

Kessler RS, Purcell EP, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Benkeser RM, Peek CJ. What does it mean to “employ” the RE-AIM model? Eval Health Prof. 2013;36:44–66.

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci. 2013;8:52.

Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5:14.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Availability of data and materials

Data abstracted for this review as a supporting file.

Authors’ contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript. SB, BP, AK, and YY collected the data. SB, AK, YY, and EH analyzed the data. SB, BP, JP, AK, FL, NG, CS, BW, JF, and LD drafted and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and gave final approval of the version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Competing interests

Fabiana Lorencatto (FL), Natalie J. Gould (NJG), and Jill J. Francis (JJF), co-authors of this paper, were authors on a study included in this review (Gould et al., 2014 [22]). The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Individual data were not included in this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human subjects were not included in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA checklist. (DOC 59 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Birken, S.A., Powell, B.J., Presseau, J. et al. Combined use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF): a systematic review. Implementation Sci 12, 2 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0534-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0534-z