Abstract

Background

Smoking, poor nutrition, risky alcohol use, and physical inactivity are the primary behavioral risks for common causes of mortality and morbidity. Evidence and guidelines support routine clinician delivery of preventive care. Limited evidence describes the level delivered in community health settings. The objective was to determine the: prevalence of preventive care provided by community health clinicians; association between client and service characteristics and receipt of care; and acceptability of care. This will assist in informing interventions that facilitate adoption of opportunistic preventive care delivery to all clients.

Methods

In 2009 and 2010 a telephone survey was undertaken of 1284 clients across a network of 56 public community health facilities in one health district in New South Wales, Australia. The survey assessed receipt of preventive care (assessment, brief advice, and referral/follow-up) regarding smoking, inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption, alcohol overconsumption, and physical inactivity; and acceptability of care.

Results

Care was most frequently reported for smoking (assessment: 59.9%, brief advice: 61.7%, and offer of referral to a telephone service: 4.5%) and least frequently for inadequate fruit or vegetable consumption (27.0%, 20.0% and 0.9% respectively). Sixteen percent reported assessment for all risks, 16.2% received brief advice for all risks, and 0.6% were offered a specific referral for all risks. The following were associated with increased care: diabetes services, number of appointments, being male, Aboriginal, unemployed, and socio-economically disadvantaged. Acceptability of preventive care was high (76.0%-95.3%).

Conclusions

Despite strong client support, preventive care was not provided opportunistically to all, and was preferentially provided to select groups. This suggests a need for practice change strategies to enhance preventive care provision to achieve adherence to clinical guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The primary behavioral risks for the most common causes of mortality and morbidity in developed countries, including Australia include tobacco smoking, inadequate nutrition, risky alcohol use and physical inactivity [1–7]. Most adults in developed nations (up to 92%) have at least one behavioral chronic disease risk [8–11]. Clinical guidelines that recommend routine, opportunistic clinician delivery of preventive care to all clients regarding multiple risks represent one strategy for reducing this preventable disease burden [12–15]. Such recommendations include assessment, and for those ‘at risk’, the provision of brief advice and referral or follow-up [12–19]. Further, both international and national guidelines [15, 18, 20] state that such care should be provided across the whole health system as a component of all ‘curative’ visits and interventions, regardless of the age or health status of the client. Review evidence supports the efficacy of preventive care [21–25].

Community health services represent a key clinical setting for the provision of preventive care [26–33] as they have historically had a focus on chronic disease prevention, early intervention and health education [29, 31], and are a key provider of primary health care in many countries [26, 29, 31]. Such services can involve contact with health care providers on multiple occasions for the delivery of specialized, non-acute care [29, 30, 34]. Despite this being a key setting, the research that has described the prevalence of preventive care delivery in this setting has been limited in terms of a focus on single risks [35–41], and on assessment of risk [34–42] and/or brief advice [35–43] rather than referral/follow-up [34–36, 40, 41]. Further, most studies have described the prevalence of preventive care in single, or a limited number of facilities [34, 37–40, 42], rather than across networks or large numbers of facilities. Finally, past studies have most commonly relied on clinician self-report, a measurement approach likely to result in an overestimate of care delivery [44]. Previous studies suggest variable and often sub-optimal levels of preventive care provision, particularly regarding client referral or follow-up [36–38, 40, 41].

If the intended benefits of preventive care provision in community health settings are to be realized, and interventions for increasing such care delivery are to be effective and appropriately targeted, a greater understanding of both the extent and variability of preventive care delivery is required. A number of client and service characteristics have previously been suggested to be associated with the delivery of preventive care in community health services, including client age (older) [38, 39], race (Caucasian) [39], socio-economic status (least disadvantaged) [34], service/provider type (health professionals versus paraprofessionals [41]; wound management, procedures or primary health care versus palliative care [34]; registered nurses versus allied health professionals [45]; prenatal clinics versus pediatric providers [46, 47], consultation type (first versus follow-up) [34], and location of practice (rural) [34]. However only one study has considered such associations with each separate element of preventive care provision across all four behavioral risks [45] and none have done this separately for each element of preventive care regarding multiple risks combined.

To address the previously described gaps in knowledge regarding the nature of preventive care provision in community health, a study was undertaken to assess the: prevalence of preventive care (assessment, brief advice, referral/follow-up) provided to community health service clients regarding four behavioral risks; association between client and service characteristics and the delivery of such preventive care; and client acceptability of such care.

Methods

A cross sectional survey was undertaken over a 12 month period between November 2009 to October 2010 across a network of 56 public community health facilities in one health district in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The district provides healthcare to approximately 840,000 people residing in urban, regional, rural and remote locations, and employs over 1,400 clinicians.

The data were obtained prior to the implementation of an intervention trial reported previously [48], and approved by the Hunter New England Local Health District (No. 09/06/17/4.03) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committees (No. H-2010-1116). The trial involved the sequential rollout of an intervention to three geographical and administratively separate groupings of the 56 community health facilities (Group 1 rural and regional, Group 2 regional, rural and remote, Group 3 urban and rural). Facilities in all three groupings involved a similar mix of community health services (nursing, allied health, child and family, diabetes, aged care, and other service types e.g. rehabilitation, chronic and complex care, women's services, migrant services, renal/dialysis, and regional health service programs), with common policies, standards, governance and performance monitoring processes. Services ineligible for inclusion were: sexual assault, palliative care, aged care assessment teams, dementia, home modification, genetics, and child protection services. Such services were deemed ineligible based upon the advice from the clinical services.

Adult clients were eligible to participate if they: had at least one face to face contact with an eligible service within the prior two weeks; spoke English; were mentally and physically capable of completing the interview (determined at interview, or by clinician/family discretion prior); and were not involved in another community health study.

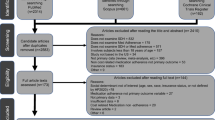

Each week, over 12 consecutive months, approximately 48 clients from each of the three facility groupings [48] within the health district were randomly selected from client electronic medical records. Selected clients were mailed an information letter and telephoned to determine eligibility and consent. Data were obtained via computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) (approximately 25 minutes), and from client electronic medical records.

Client and service characteristic information collected by the CATI included: employment status; Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status; marital status; highest level of education achieved; and conditions in the prior two months for which the client needed to take medication or receive medical attention. Client age, gender, country of birth, postcode, service attended (nursing, allied health, child and family, diabetes, aged care, and other service types) and number of visits to the service in the prior 12 months were obtained from client medical records.

Clients were asked to indicate, in the month before seeing the service: their frequency of smoking tobacco products [49]; the number of serves of fruit and of vegetables typically eaten per day [50]; how often they had a drink containing alcohol, the number of standard drinks consumed on a typical drinking day, and how often they consumed four or more standard drinks on any one occasion [51]; and how many days a week they usually did 30 minutes or more of physical activity [52].

Based on national guidelines [53–56], clients were considered to be ‘at risk’ and hence require a preventive health education response if they reported that they: smoked any tobacco products [53]; ate less than two serves of fruit or five serves of vegetables per day [55]; drank more than two standard alcoholic drinks on a typical drinking day or four or more standard drinks on any one occasion [56]; or engaged in less than 30 minutes of physical activity on at least five days of the week [54].

The prevalence of three forms of preventive care was measured. For assessment of behavioral risk status, clients were asked if, during an appointment with the service, the clinician asked: if they smoked any tobacco products; how much fruit and how many vegetables they ate; how much alcohol they drank; and how much physical activity they participated in (yes, no, don’t know).

For provision of brief advice, clients who reported being ‘at risk’ as defined by national guidelines [53–56] were asked whether the clinician advised them: to quit smoking or consider using Nicotine Replacement Therapy; to eat more fruit and/or more vegetables; to reduce the amount of alcohol they consume; or to do more physical activity (yes, no, don’t know).

For the provision of referral/follow-up care, clients who reported smoking were asked if they were offered referral to a free NSW Quitline telephone service. Clients who reported inadequate fruit and/or vegetable intake or physical inactivity were asked if they were offered referral to a free ‘Get Healthy Information and Coaching’ telephone service. Clients with ‘at risk’ alcohol use were asked if they were advised to visit their General Practitioner/Aboriginal Medical Service (GP/AMS). All ‘at risk’ clients were asked if the clinician offered to send a summary of their health risks to their GP/AMS (yes, no, don’t know).

To measure client acceptability of preventive care provision, all clients were asked if it was acceptable for clinicians to assess their health risk behaviors, and for ‘at risk’ clients, if it was acceptable for clinicians to provide brief advice and arrange further support for each risk individually and for all risks combined (strongly disagree, disagree, unsure, agree, strongly agree).

Statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS (version 9.2). Client residential postcodes were used to determine disadvantage (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA]; cut points: higher NSW half [>991] versus lower NSW half [<=991]) [57] and remoteness (Access/Remoteness Index of Australia [ARIA]; major cities versus regional remote towns) [58]. Descriptive statistics were used to describe client and service characteristics. Comparison of participant and non-participant characteristics was undertaken using chi-square analyses (p < .01).

Descriptive statistics were used to examine for each risk separately and for all risks combined, the prevalence of: clients who were ‘at risk’; clinician assessment of risk; clinician brief advice; clinician offer of referral/follow-up; and client acceptability of such care. The analyses were weighted based on the three facility groupings [48] to ensure that the sample was representative of all clients attending the community health services across the health district. The prevalence of care provision for all risks combined was defined as: assessment for all four risks; the provision of brief advice for all of a client’s self-reported risks; and either an offer to send a health risk summary of all their risks to the clients GP/AMS, or an offer of referral/follow-up for all their risks individually (i.e. telephone counseling, or GP/AMS for alcohol).

Associations between client/service characteristics and the provision of each form of care (assessment, brief advice and an offer of referral/follow-up for each individual risk and for all risks combined) were initially analyzed using chi-square analysis. Logistic regression analyses were subsequently undertaken separately for the provision of assessment and brief advice for each of the four individual risks (8 regression models). Regression analyses were not undertaken for referral/follow-up for the four individual risks due to inadequate sample size. Separate chi-square and regression analyses were similarly undertaken to determine such associations with the provision of all three forms of care (assessment, brief advice and referral/follow-up) for all risks combined (3 models). For each of the regression models the analysis was adjusted for the three facility groupings to account for potential cluster effect. Variables with a p-value of 0.20 or less from the chi-square analyses were included in each separate regression model, utilizing a backward stepwise selection process whereby the variable with the highest p value was removed until all predictors in the model had a p value less than .01. Any potential interaction between variables that remained in each of the final models were also examined to ensure the model was sound and that results for each variable could be interpreted independently from other variables [59].

Results

Sample

Of 2034 clients randomly selected from the health district’s client electronic medical records, 1767 (86.9%) were eligible. A total of 1284 eligible clients participated in the survey (72.7%) (Table 1) (Facility grouping 1: n = 427, 33.3%; facility grouping 2: n = 408, 31.8%; facility grouping 3: n = 449, 35.0%). This sample size of 1284 allows for estimation of +/− 4.6% of the proportions of the variables of interest after accounting for potential cluster effect from the three facility groupings. Compared to eligible non-participants, participants were less likely to be of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin (9.1% vs 3.4%, p < .0001) and less likely to come from regional/remote towns (81.4% vs 75.6%).

Behavioral risk prevalence

Eighty-eight per cent of clients reported at least one risk, with inadequate fruit or vegetable consumption the most prevalent (80.5%) and smoking the least (13.3%) (Table 2).

Prevalence of preventive care delivery

There was an inverse relationship between the prevalence of risk and the prevalence of preventive care, whereby care was most frequently provided for smoking (despite being the least prevalent risk) and least frequently for inadequate fruit or vegetable consumption (despite being most prevalent) (Table 2). Sixty per cent of all clients had their smoking status assessed, and 61.7% and 4.5% of smokers were provided brief advice and offered a referral respectively. Twenty-seven per cent of all clients had their fruit and vegetable consumption assessed, and 20.0% and 0.9% of ‘at risk’ clients were provided with brief advice and offered a referral respectively. Sixteen percent of clients were assessed for all four risks. Of those with at least one risk, 16.2% were provided with brief advice for all risks, 15.2% were offered to have a risk summary sent to their GP/AMS, and 0.6% were offered a specific referral for each risk.

Client and community health service characteristics associated with preventive care delivery

Individual risks

Service type was the only variable found to be significantly associated with care in all the final regression models, with allied health services generally having significantly lower odds of care provision than most other service types for assessment and provision of advice for each risk (Table 3). Compared to allied health services, diabetes services had the highest relative odds of care for each risk.

Client characteristics associated with assessment or brief advice varied according to the risk (Table 3). Males were more likely to be assessed for smoking and physical activity. Aboriginal clients were more likely to be provided brief advice regarding fruit or vegetable consumption. Compared to clients with one appointment (of which the majority were new clients), clients with between 5–11 prior service appointments in the last 12 months were less likely to have alcohol status assessed, and clients with 12 or more appointments were more likely to have physical activity assessed. Clients most socio-economically disadvantaged, and those unemployed (compared to retired clients) were more likely to have alcohol status assessed.

All risks

Service type was the only characteristic that remained significant in all three regression models for all three forms of preventive care. Compared to allied health services, diabetes and ‘other’ services were more likely to provide assessment, advice and referral/follow-up (Table 4).

No interactions were found between variables that remained in the final regression for any of the models.

Client acceptability of preventive care

Acceptability of assessment for the four individual risks ranged from 88.4% to 95.3%; for brief advice, 86.3% to 89.0%; and for arranging further support, from 78.9% to 85.3% (Table 2). The majority of clients found it acceptable for community health services to assess all risks (82.9%), and when ‘at risk’, for them to provide brief advice (83.0%) and to arrange further support (76.0%) for all risks.

Discussion

The study findings suggest community health clinicians do not provide preventive care in a manner that is consistent with clinical guidelines. The prevalence of clinician assessment did not exceed 60% for any individual risk, and only 16% of clients were assessed for all four risks. Further, the form of preventive care most likely to result in a reduction of risk – referral/follow-up [14], was offered to less than 5% of clients for individual risks, and to less than 1% for all risks. Preventive care was preferentially provided to clients according to the type of behavioral risk and to the type of service attended. Strong client support existed for the provision of preventive care.

Comparison of the prevalence of preventive care found in this study with that previously reported is constrained by differences between studies in the definition of preventive care [34, 42], the behavioral risks addressed [34, 42, 43], data collection methods [34–43], and the type of client [35, 41–43]. The prevalence of smoking assessment has been reported in two previous medical record audit studies to range from 30% [36] to 71% [38], as compared to 59.9% in this study. One Australian study utilizing clinician self-report [34] has reported assessment of the four behavioral risks to occur for between 61.5% and 72.0% of clients, as compared to the 27.0% to 59.9% reported by clients in this study. The prevalence of assessment of all four risks combined, was lower in this study than that reported in an Australian clinician report-based study (16.1% vs 54.1%) [34].

With regard to the provision of brief advice, the prevalence in this study ranged from 20.0% for inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption to 61.7% for smoking, higher than that found in a medical records audit study (2% to 3% across the four risks) [43]. The prevalence of referral/follow-up found in this study (0.9% to 4.5% for individual risks and 0.6% for all risks) was generally lower than that found in clinician self-report studies regarding smoking (0% to 31.5%) [40, 41], and multiple risks (86.3%) [34]. However these higher proportions are likely to be attributable to differences in the definition of referral/follow-up, whereby this could have included communicating the clients smoking plans and progress to the team [41] or brief advice and/or referral [34]. Overall, the provision of each of the three preventive care elements was delivered in a manner incongruent to the prevalence of the four behavioral risks (whereby despite being the least prevalent risk, smoking care was most frequently provided, and nutrition care was least frequently provided despite being the most prevalent risk), possibly partly attributable to the more well established smoking cessation guidelines [60].

The type of community health service attended was consistently found to be associated with preventive care delivery, with allied health services among those least likely to provide such care, and diabetes and ‘other’ services more likely to do so. Previous research has similarly found that services with a focus on chronic disease treatment [9, 34, 61, 62] were more likely to provide preventive care [41, 45], and that allied health professionals were the least likely to do so [45]. Such a finding is consistent with the findings of studies conducted in other clinical settings which suggest that when preventive care is provided, it occurs not from an opportunistic primary prevention perspective [13, 14], but as an element of the diagnosis and treatment of risk-related conditions such as tobacco or obesity-related disease [63–73]. These findings confirm the need for additional strategies to support community health clinicians to adopt an opportunistic primary prevention approach to the provision of preventive care to all clients, and reinforce that practice change strategies are required to support policies regarding the delivery of such care. Furthermore, the findings suggest additional strategies are required to support services that traditionally do not deliver preventive care, and to support all clinicians to provide this for all clients, regardless of their demographic characteristics. In light of guidelines recommending all primary care clinicians- which includes allied health professionals- to provide preventive care across the four health risk behaviors [13] further professional development and practice redesign is required in order to address the current gap in care provision by such professionals.

Limited evidence has been reported describing the effectiveness of intervention strategies to increase the provision of any form of preventive care in community health settings [35, 40, 43]. Practice change theories [74–77] and evidence from practice change interventions in other clinical settings however suggest that a multi-strategic approach is most likely to increase clinician provision of preventive care on an opportunistic basis [18, 78–83].

This study is one of few to involve a cross-sectional sample of clients from a large number of community health service facilities, a design that allows for a diverse range of clients and community health service types to be included. Secondly, the study is believed to be the first to comprehensively address separately the prevalence of three recommended forms of preventive care applied to four chronic disease behavioral risks in the community health setting. The study is one of few to have utilized client self-report [35, 39], which has demonstrated greater accuracy than clinician self-report or medical records audit for reporting clinician performance regarding counseling behaviors [84]. While using a self-reported outcome possibly overestimated care provision [69, 85, 86], this re-enforces the low levels of preventive care delivery reported. The accuracy of outcome measures may have been affected by client recall over an extended period [84], however measurement via direct observation is not always feasible or ethical, and can be difficult and costly [84].

Conclusions

The finding in this study that almost all community health clients report that the provision of preventive care is acceptable, is consistent with previous studies of clients from community health services [34, 35, 62] and other clinical settings [87], and provides a strong basis for clinicians to deliver this form of care. Such findings strengthen the need for strategies that facilitate clinician delivery of preventive care to be utilized if clinical guidelines are to be adhered to.

References

Prochaska JJ, Spring B, Nigg CR: Multiple health behavior change research: an introduction and overview. Prev Med. 2008, 46: 181-188. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.001.

World Health Organisation (WHO): The World Health Report: Reducing risks, promoting healthy lifestyle. 2002, Geneva: WHO

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): Australia’s Health 2010. 2010, Canberra: AIHW

Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J: Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009, 373: 2223-2233. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7.

Rehm J, Taylor B, Room R: Global burden of disease from alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006, 25: 503-513. 10.1080/09595230600944453.

Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M: The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ. 2005, 83: 100-108.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL: Comparative quantification of health risks. Global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. 2004, Geneva: World Health Organisation

Fine LJ, Philogene GS, Gramling R, Coups EJ, Sinha S: Prevalence of multiple chronic disease risk factors: 2001 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 27: 18-24. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.017.

Coups EJ, Gaba A, Orleans CT: Physician screening for multiple behavioral health risk factors. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 27: 34-41. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.021.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and O’Brien, K: Living dangerously: Australians with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. 2009, Canberra: AIHW

Hausdorf K, Eakin E, Whiteman D, Rogers C, Aitken J, Newman B: Prevalence and correlates of multiple cancer risk behaviors in an Australian population-based survey: results from the Queensland Cancer Risk Study. Cancer Cause Control. 2008, 19: 1339-1347. 10.1007/s10552-008-9205-y.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners: Guidelines for Preventive Activties in General Practice (The Red Book) 7th Edition. 2009, Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

US Department of Health and Human Services: The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services 2010–2011. 2010, Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Glasgow RE, Goldstein MG, Ockene JK, Pronk NP: Translating what we have learned into practice. Principles and hypotheses for interventions addressing multiple behaviors in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 27: 88-101. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.019.

Ministry of Health: New Zealand Smoking Cessation Guidelines. 2007, Wellington: Ministry of Health

West R, McNeill A, Raw M: Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: an update. Thorax. 2000, 55: 987-999. 10.1136/thorax.55.12.987.

New South Wales (NSW) Department of Health: Guide for the management of nicotine dependant inpatients. 2002, Gladesville, NSW: Better Health Centre

Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB: Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. 2008, Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service

Laws RA, Kemp LA, Harris MF, Davies GP, Williams AM, Eames-Brown R: An exploration of how clinician attitudes and beliefs influence the implementation of lifestyle risk factor management in primary healthcare: a grounded theory study. Implement Sci. 2009, 4: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-66.

National Preventative Health Taskforce: Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. 2010, Canberra: National Preventative Health Strategy- The roadmap for action

Brunner E, Rees R, Ward K, Burke M, Thorogood M: Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD002128-10.1002/14651858.CD002128. 4

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C: Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD004148-10.1002/14651858.CD004148. 2

Foster C, Melvyn H, Thorogood M: Interventions for improving physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, CD003180-10.1002/14651858.CD003180. 1

Rice VH, Stead LF: Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, CD001188-10.1002/14651858.CD001188. 1

Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF: Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD001837-10.1002/14651858.CD001837. 3

Laws RA, Davies GP, Williams A, Eames-Brown R, Amoroso C, Harris M: Community Health Risk Factor Management Research Project. Final Report Februrary 2008. A feasibility study. 2008, Sydney: University of NSW

New South Wales (NSW) Department of Health: A new direction for NSW. State Health Plan. Towards 2010. 2007, Sydney: NSW Department of Health

Australian Government: A healthier future for all Australians. Final report. 2009, Canberra: Australian Government

New South Wales (NSW) Health: Integrated primary and community health policy 2007–2012. 2006, North Sydney, NSW, Australia: NSW Health

Eagar K, Owen A, Cranny C, Samsa P, Thompson C: Community Health: The state of play in New South Wales. A report for the NSW Community Health Review. 2008, University of Wollongong: Centre for Health Service Development

Owen A: Community Health: The evidence base. A report for the NSW Community Health Review. 2010, University of Wollongong: Centre for Health Service Development

Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J: Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 27: 61-79. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.023.

Truman BI, Smith-Akin CK, Hinman AR, Gebbie KM, Brownson R, Novick LF: Developing the Guide to Community Preventive Services-overview and rationale. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000, 18: 18-26.

Laws RA, Jayasinghe UW, Harris MF, Williams AM, Powell DG, Kemp LA: Explaining the variation in the management of lifestyle risk factors in primary health care: A multilevel cross sectional study. BMC Publ Health. 2009, 9: 165-10.1186/1471-2458-9-165.

Bakker MJ, Mullen PD, de Vries H, van Breukelen G: Feasibility of implementation of a Dutch smoking cessation and relapse prevention protocol for pregnant women. Patient Educ Couns. 2003, 49: 35-43. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00038-1.

DePue JD, Goldstein MG, Schilling A, Reiss P, Papandonatos G, Sciamanna C: Dissemination of the AHCPR clinical practice guideline in community health centres. Tob Control. 2002, 11: 329-335. 10.1136/tc.11.4.329.

Klink K, Lin S, Elkin Z, Strigenz D, Liu S: Smoking cessation knowledge, attitudes, and practice among community health providers in China. Fam Med. 2011, 43: 198-200.

Maizlish NA, Ruland J, Rosinski ME, Hendry K: A systems-based intervention to promote smoking as a vital sign in patients served by community health centers. Am J Med Qual. 2006, 21: 169-177. 10.1177/1062860606287190.

Pollak KI, Yarnall KS, Rimer BK, Lipkus I, Lyna PR: Factors associated with patient-recalled smoking cessation advice in a low-income clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002, 94: 354-363.

Borrelli B, Lee C, Novak S: Is provider training effective? Changes in attitudes towards smoking cessation counseling and counseling behaviors of home health care nurses. Prev Med. 2008, 46: 358-363. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.09.001.

Johnson JL, Malchy LA, Ratner PA, Hossain S, Procyshyn RM, Bottorff JL: Community mental healthcare providers’ attitudes and practices related to smoking cessation interventions for people living with severe mental illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2009, 77: 289-295. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.013.

Bailie RS, Togni SJ, Si D, Robinson G, d’Abbs PH: Preventive medical care in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory: A follow-up study of the impact of clinical guidelines, computerised recall and reminder systems, and audit and feedback. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003, 3: 15-10.1186/1472-6963-3-15.

Si D, Bailie RS, Dowden M, O’Donoghue L, Connors C, Robinson GW: Delivery of preventive health services to Indigenous adults: Response to a systems-oriented primary care quality improvement intervention. Med J Australia. 2007, 187: 453-457.

Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, Ross-Degnan D: Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999, 11: 187-192. 10.1093/intqhc/11.3.187.

Laws RA, Kirby SE, Davies GPP, Williams AM, Jayasinghe UW, Amoroso CL: “Should I and Can I?”: A mixed methods study of clinician beliefs and attitudes in the management of lifestyle risk factors in primary health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008, 8: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-44.

Bonollo DP, Zapka JG, Stoddard AM, Ma Y, Pbert L, Ockene JK: Treating nicotine dependence during pregnancy and postpartum: Understanding clinician knowledge and performance. Patient Educ Couns. 2002, 48: 265-274. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00023-X.

Zapka JG, Pbert L, Stoddard AM, Ockene JK, Goins KV, Bonollo D: Smoking cessation counseling with pregnant and postpartum women: A survey of community health center providers. Am J Public Health. 2000, 90: 78-84.

McElwaine KM, Freund M, Campbell EM, Knight J, Slattery C, Doherty EL: The effectiveness of an intervention in increasing community health clinican provision of preventive care: A study protocol of a non-randomised, multiple-baseline trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011, 11: 1-9. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-1.

Heatherton T, Kozlowski L, Frecker R, Faberstrom K: The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revison of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991, 86: 1119-1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS): National Nutrition Survey selected highlights Australia 1995. 1997, Canberra: ABS

Babor, T F Higgins-Biddle, J C, Saunders, J B, and Monteiro, Maristela G: AUDIT. The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care. 2001, Geneva: World Health Organisation

Marshall A, Hunt J, Jenkins D: Knowledge of and preferred sources of assistance for physical activity in a sample of urban Indigenous Australians. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008, 5: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-22.

Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy: National Tobacco Strategy, 2004–2009: The Strategy. 2004, Canberra: Australian Government

Department of Health and Aged Care: An active way to better health. National physical activity guidelines for adults. 1999, Canberra: Australian Government

National Health and Medical research Council (NHMRC): Dietary guidelines for Australian adults. 2003, Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing

National Health and Medical research Council (NHMRC): Australian guidelines to reduce health risk from drinking alcohol. 2009, Canberra: Australian Government

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS): SEIFA: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas. 2008, Canberra: ABS

Department of Health and Aged Care: Measuring remoteness: Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA). 2001, Canberra: Australian Government

Hosmer D, Lemeshow S: Applied logistic regression. 2000, Canada: John Wiley & Sons Inc

Fiore MC, Bailey W, Cohen S: Smoking cessation: clinical practice guideline no. 18. 1996, Rockville, US, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: US Department of Health and Human Services

Glasgow RE, Eakin EG, Fisher EB, Bacak SJ, Brownson RC: Physician advice and support for physical activity: Results from a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001, 21: 189-196. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00350-6.

Christl B, Chan B, Laws RA, Williams A, Davies GP, Harris Mark F: Clients’ experience of brief lifestyle interventions by community nurses. 2011, Aust J Prim: Health

Heard T, Daly J, Bowman J, Freund M, Wiggers J: A cross-sectional survey of the prevalence of environmental tobacco smoke preventive care provision by child health services in Australia. BMC Publ Health. 2011, 11: 324-10.1186/1471-2458-11-324.

Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, Sakrouge R, Lecathelinais C, Knight J: Increasing hospital-wide delivery of smoking cessation care for nicotine-dependent in-patients: A multi-stategic intervention trial. Addiction. 2009, 104: 839-849. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02520.x.

Wye PM, Bowman JA, Wiggers JH, Baker A, Knight J, Carr VJ: Smoking restrictions and treatment for smoking: Policies and procedures in psychiatric inpatient units in Australia. Psychiatr Serv. 2009, 60: 100-107. 10.1176/appi.ps.60.1.100.

Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, Sakrouge R, Wiggers J: Smoking care provision in smoke-free hospitals in Australia. Prev Med. 2005, 41: 151-158. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.044.

Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, McElduff P, Walsh RA, Sakrouge R: Smoking care provision in hospitals: A review of prevalence. Nic Tob Res. 2008, 10: 757-774. 10.1080/14622200802027131.

Wolfenden L, Wiggers J, Knight J, Campbell E, Spigelman A, Kerridge R: Increasing smoking cessation care in a preoperative clinic: A randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2005, 41: 284-290. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.011.

Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Silverman CB, Chang Y, Regan S, Schneider LI: Measuring provider adherence to tobacco treatment guidelines: A comparison of electronic medical record review, patient survey, and provider survey. Nic Tob Res. 2005, 7: 35-43. 10.1080/14622200500078089.

Hensrud DD: Clinical preventive medicine in primary care: Background and practice: 1. Rationale and current preventive practices. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000, 75: 165-172.

Pham HH, Schrag D, Hargraves JL, Bach PB: Delivery of preventive services to older adults by primary care physicians. JAMA. 2005, 294: 473-481. 10.1001/jama.294.4.473.

Flocke SA, Clark A, Schlessman K, Pomiecko G: Exercise, diet, and weight loss advice in the family medicine outpatient setting. Fam Med. 2005, 37: 415-421.

Schnoll RA, Rukstalis M, Wileyto EP, Shields AE: Smoking cessation treatment by primary care physicians: An update and call for training. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31: 233-239. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.05.001.

Norman GR, Schmidt HG: The psychological basis of problem-based learning: A review of the evidence. Acad Med. 1992, 67: 557-565. 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00002.

Azjen I: The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1991, 50: 179-211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Bandura A: Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. 1986, New York: Prentice-Hall

Rogers EM: Diffusion of Innovations. 1995, New York: The Free Press, 4

Curry SJ, Keller PA, Orleans CT, Fiore MC: The role of health care systems in increased tobacco cessation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008, 29: 411-428. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090934.

Dijkstra R, Wensing M, Thomas R, Akkermans R, Braspenning J, Grimshaw J: The relationship between organisational characteristics and the effects of clinical guidelines on medical performance in hospitals, a meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006, 6: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-53.

Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Ramsay C, Fraser C: Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 14-20.

Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, Sakrouge R, McElduff P, Walsh R: Increasing smoking cessation care provision in hospitals: A meta-analysis of intervention effect. Nic Tob Res. 2009, 11: 650-662. 10.1093/ntr/ntp056.

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, Thomson O’Brien MA, Oxman AD: Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, CD000259-10.1002/14651858.CD000259. 2

Grol R, Wensing M, Hulscher M, Eccles M: Theories on implementation of change in healthcare. Improving patient care: The implementation of change in clinical practice. Edited by: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M. 2004, London: Elsevier

Hrisos S, Eccles MP, Francis JJ, Dickinson HO, Kaner EFS, Beyer F: Are there valid proxy measures of clinical behaviour? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009, 4: 37-10.1186/1748-5908-4-37.

Nicholson JM, Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, McCarty MC, Vessey J: Patient recall versus physician documentation in report of smoking cessation counselling performed in the inpatient setting. Tob Control. 2000, 9: 382-388. 10.1136/tc.9.4.382.

Ward JE, Sanson-Fisher RW: Accuracy of patient recall of opportunistic smoking cessation advice in general practice. Tob Control. 1996, 5: 110-113. 10.1136/tc.5.2.110.

Duaso MJ, Cheung P: Health promotion and lifestyle advice in a general practice: What do patients think?. J Adv Nurs. 2002, 39: 472-479. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02312.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/13/167/prepub

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken with infrastructure support from the Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI), and funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, ID = 1016650). Evaluation and data collection was conducted at Population Health - Hunter New England Local Health District. This project was initiated by the investigators. With grateful acknowledgements of investigators on the grant not mentioned in authors; members of the Preventive Care team; members of the Aboriginal Advisory group; interviewers; electronic medical records team; and community health service clients, staff and managers for their contribution to the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KM led the development of this manuscript. Authors MF, JK, and JW conceived the intervention concept. Authors MF, EC, JB, LW, JK, PW, JW, and SM secured grant funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council. SM provided clinical approval, leadership and liaison with community health district staff. CL provided statistical assistance regarding data analysis. All authors contributed to the research design and trial methodology and contributed to, read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

McElwaine, K.M., Freund, M., Campbell, E.M. et al. The delivery of preventive care to clients of community health services. BMC Health Serv Res 13, 167 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-167

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-167