Abstract

Background

The early initiation of breastfeeding (EIBF), or timely initiation of breastfeeding, is the proportion of children put to the breast within one hour of birth. It is an important strategy for reducing perinatal and infant morbidity and mortality, but it remains under practiced in Ethiopia. The aim of the study was to assess the prevalence and the predicting factors associated with EIBF.

Methods

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted in 634 mothers in Dale Woreda, South Ethiopia. Multistage cluster sampling was used to select participating mothers. EIBF was outcome variable whereas sociodemographic characteristics and knowledge and practice of maternal health service were explanatory variables. A face-to-face interview using a pretested semi-structured questionnaire was done from September 2012 to March 2013. To investigate predicting factors, bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was done.

Results

A total of 634 mothers of children under 24 months were interviewed. During the time of data collection, 94.3% of the mothers had breastfed. The prevalence of EIBF was 83.7%. Ownership of the house was a significant predicting factor for EIBF. Mothers who lived in rented houses were significantly less likely (60%) to initiate breastfeeding within one hour of birth compared to mothers who owned their own house: Adjusted odds ratio 0.40 (95% Confidence Interval 0.16, 0.97).

Conclusion

More than three-fourths of mothers initiated breastfeeding within an hour. Findings from our study suggest that improving the mother's socioeconomic status as reflected by house ownership, being a significant predictor of EIBF, would have a central role in improving EIBF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The early initiation of breastfeeding (EIBF), or timely initiation of breastfeeding, is the proportion of children born who were put to the breast within one hour of birth [1]. EIBF practice in low and middle-income countries is comparatively higher than in developed countries [2]. A systematic review of studies conducted in Asia, Africa, and South America found the prevalence of EIBF in Ethiopia ranged from 41.6 to 62.6% [3]. Another investigation from fifty-three World Health Organization (WHO) European member states described rates of EIBF as 5 to 84% [4].

Breastfeeding has been universally accepted as the easiest, cost effective and most successful intervention for the satisfactory physical and mental health of children [5–8]. Recent studies in Ethiopia, Ghana, Bolivia and Madagascar found that breastfeeding could prevent 20% to 22% of neonatal deaths [6, 7, 9].

Late initiation of breastfeeding increases the risk of morbidity and mortality such as diarrhea byfivefold [10]. Infectious diseases and malnutrition due to poor breastfeeding practice are major causes of infant death in developing countries [8, 10]. Even though there has been a decrement from 1995 to 2010, the current neonatal mortality rate in Ethiopia is still 29 deaths per 1000 live births [11].

Predicting factors for EIBF include: place of residence and delivery [12]; postnatal care and educational status [9]; unemployment benefit, social welfare and household income [13]; maternal age and socioeconomic status [14]; marital status, smoking, breastfeeding exposure [15]; parity [16]; and antenatal care [17]. Conversely, a prospective study done in India discovered parental education, living condition, number of antenatal visits, birthweight, cultural habit of the population, postnatal breastfeeding advice, previous breastfeeding exposure, and mother’s employment had no significant association with EIBF [18].

Breastfeeding practice is a vital component of primary health care. Realizing the benefit of EIBF, as outlined in the United Nation (UN) sustainable development goals and the WHO millennium development goals, the Ethiopian government developed an infant and young child feeding guideline in 2004. In addition, the government has been implementing the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) and the community integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) program [19, 20]. However, EIBF is still below the standard recommendation in Ethiopia, perhaps due to the lack of a culturally oriented approach [9]. In addition, predictors of EIBF have not been previously reported in the study area, and this study will go a long way in addressing this gap. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and predicting factors of EIBF.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Dale Woreda, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR). Dale Woreda was selected because of the absence of any previous study, as far as we know, and it is the most densely populated in the SNNP. It is believed that these factors possibly limit the knowledge and practice of EIBF in Dale Woreda. Dale Woreda is located in SNNPR about 326 km south from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The total area is 302.12 km2 with a total population size of 260,767 (132,679 females and 128,088 males). The population density is estimated to be 736 persons per km2 and the average land holding is 0.6 ha per person. There are 36 kebeles (smallest administrative unit) with 2087 women headed, and 34,189 men headed households. The Woreda has seven health centers, 29 health posts and one hospital [21].

Study design and sample

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted in 634 mothers of children under the age of 24 months from September 2012 to March 2013. All mothers who had had a child less than 24 months of age, a term birth, who were permanent residents, and capable of providing informed consent were included. Mothers who were not available during data collection and capable of independent communication were excluded.

Sample size determination

The required sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula with the following assumptions:

n = required sample size

p = prevalence for EIBF, which was 52.4%, in Goba Woreda, Southeast Ethiopia [9].

d = marginal error between sample statistics and the population parameter (5%)

z = critical value at 95% confidence interval (1.96)

Given 1.5 design effect and 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 634.

Sampling procedure

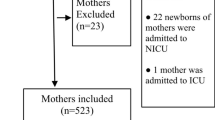

Multistage sampling technique was used for selecting mothers. First, simple random sampling method was used to select six kebeles out of 36 kebeles. Second, total number of mothers (2960) who had children aged less than 24 months was defined by census. Finally, systematic random sampling (sampling interval = 5) was used to select an individual mother (Fig. 1).

Data collection and instrument

A semistructured questionnaire was developed (MG and GM had a leading role) presuming all the relevant variables were included. First, we identified major indicators of breastfeeding and the related parameters based on previous research evidence, the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) questionnaire, and WHO infant feeding guidelines. Then, the questionnaire was developed in English and professionals fluent in both languages translated it to Amharic (local language) using backward-forward approach. Next, it was pretested. Finally, redundant, lengthy and vague questions were revised. In addition, probing phrases were added for some of the questions. The questionnaire has three parts; section 1: sociodemographic characteristics of mothers, section 2: knowledge and practice on maternal health service, section 3: breastfeeding practice. An additional word file shows this in more detail (see Additional file 1). During data collection, completeness of filled questionnaire was ensured. A replacement technique from closest household was used whenever an eligible mother was not available for the data collection.

Variables

EIBF was the outcome variable. Taking into account the definition of WHO [1], initiating breastfeeding within one hour of birth was coded as ‘1’, whereas after one hour of birth was coded as ‘0’ for logistic regression analysis. Sociodemographic characteristics (maternal age, age of child, sex of child, birthweight of child, marital status, educational status, ethnicity, religion, household income) and maternal health service (place of birth, assistance during delivery, health education on breastfeeding, source of information about breastfeeding, antenatal care) were explanatory variables. These explanatory variables were chosen based on previous research evidence, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey questionnaire, and WHO infant feeding guidelines.

Data processing and analysis

Printed frequency was used to checking accuracy, consistency, and missed values of variables. All variables p-value ≤ 0.05 in the bivariate logistic regression analysis were included in multiple logistic regression model. Variables p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered as an independent predicting factor for EIBF in the final model. The strength of association was described using odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software package (version 16.0) was used to process and analyze all data.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 634 mothers of children less than 24 months were interviewed. The mean ± SD age of mothers was 26 ± 5.04 years. The mean ± SD of the age of children was 13 ± 6.31 months (Table 1).

Knowledge and practice of maternal health service

The main sources of breastfeeding information were health workers (21.5%), husbands/partners (21.9%), grandmothers (28.7%), and friend/neighbours (29.0%). As presented in Table 2, 42.6% of mothers had antenatal care. More than half (56.3%), mothers delivered their babies at home.

Early initiation of breastfeeding

Five hundred ninety-eight (94.3%) of the mothers had breastfed at the time of data collection. Of those who had breastfed, 517 (83.7%) mothers initiated breastfeeding within one hour after birth.

EIBF and predicting factors

As presented in Table 3, bivariate test of association, strongly significant predicting factors of EIBF were ethnicity, ownership of the house, number of living children, antenatal care, and place of birth.

After an adjustment for all confounding factors, multivariate test of association in Table 4, living in a rented house was found a significant predicting factor. Mothers who lived in rented houses were significantly less likely (60%) to initiate breastfeeding within one hour of birth as compared to mothers who lived in their own houses (p-value = 0.04, OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.16, 0.97).

Discussion

EIBF reduces infant morbidity and mortality and has economic advantage. Even though the benchmark has not been achieved, the Ethiopian government has initiated different infant and child feeding strategies to optimize EIBF. In this study, we sought prevalence and predicting factors of EIBF. To our knowledge, this study was the first in Dale Woreda where almost half million people are living.

In this study, prevalence of EIBF was 83.7%. According to the WHO infant and young child feeding rating on EIBF, a 0–29% prevalence of EIBF is considered as poor, 30–49% as fair, 50–89% as good and 90–100% as very good [22]. Therefore, our result showed that coverage of EIBF in Dale Woreda was good and stands at 83.7%. This finding was similar with cross-sectional study reports [23, 24], but higher than other studies finding in Ethiopia of 52.4–63% [9, 25]. On the other hand, it was lower than the prevalence rate in rural central Ethiopia 92% [25], India 97.5% [26] and Panama 89.8v% [27].

Ownership of the house was found to be an independent significant predicting factor for EIBF but not maternal age, maternal educational status, antenatal care, place of birth, and parity. This is contrary to the systematic review of studies conducted in Asia, Africa, and South America which identified that the place of delivery, maternal self-confidence and self-efficacy, birth attendant, mode of delivery, parity, cultural practices and beliefs, antenatal care, birth interval, infant birthweight, employment status, occupation, educational status, economic status, postnatal advice on breastfeeding, maternal ill health, breast problem, lack of information, and residence, were significant predicting factors for EIBF [3, 28].

Given the above inconsistencies, prevalence and predicting factors of EIBF are substantially different among regions, nations and continents. This might be due to the difference in study population, sample size, sampling procedure, study period, and setting.

Policy and practice implication

Despite international collaboration, adaption and implementation of program and policy, EIBF is still below the standard recommendation in Ethiopia [9, 19, 20]. As a result, neonatal mortality is high in Ethiopia. This study also revealed that one out of every five children were not breastfed within one hour of birth, even if all children were expected to breastfed within one hour. House ownership was significantly associated with EIBF implying the importance of economic dependence of mothers. It is believed this also limits access to modern health care. Thus, creating job opportunity, building economic capacity of women sustainably, and strengthening the national infant and young child feeding (IYCF) intervention would have immense advantage to increase EIBF and reducing neonatal mortality rate.

Strength and limitation

The strength of this study: a community-based study which enables to minimize selection bias; and a large number of mothers included perhaps it increases power and external validity of the study. However, this study has certain limitations. Complex sample analysis, to compensate for unequal probability of recruiting samples from the community, was not done. This study was also subjected to potential recall and social desirability bias. Furthermore, this study shares the limitations of cross-sectional studies.

Conclusions

More than three-fourths of mothers were practicing EIBF. Findings from our study suggest that improving a mothers socioeconomic status as reflected by house ownership is a significant predictor of EIBF and would have a central role in improving EIBF. Future researchers should conduct a longitudinal qualitative and quantitative study on economically disadvantaged breastfeeding mothers.

Abbreviations

- IMCI:

-

Integrated management of childhood illness

- IYCF:

-

Infant and young children feeding

- MDG:

-

Millennium Development Goal

- SNNPR:

-

Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations Children’s Fund

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, Sankar MJ, Walker N, Rollins NC, Group TL. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90.

Patel A, Bucher S, Pusdekar Y, Esamai F, Krebs NF, Goudar SS, Chomba E, Garces A, Pasha O, Saleem S, Kodkany BS, Liechty EA, Kodkany B, Derman RJ, Carlo WA, Hambidge K, Goldenberg RL, Althabe F, Berrueta M, Moore JL, McClure EM, Koso-Thomas M, Hibberd PL. Rates and determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breast feeding at 42 days postnatal in six low and middle-income countries: a prospective cohort study. Reprod Health. 2015;12 Suppl 2:S10.

Esteves TM, Daumas RP, Oliveira MI, Andrade CA, Leite IC. Factors associated to breastfeeding in the first hour of life: systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(4):697–708.

Bosi AT, Eriksen KG, Sobko T, Wijnhoven TM, Breda J. Breastfeeding practices and policies in WHO European region member states. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(4):753–64.

Mullany LC, Katz J, Li YM, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Darmstadt GL, Tielsch JM. Breast-feeding patterns, time to initiation, and mortality risk among newborns in southern Nepal. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):599–603.

Baker EJ, Sanei LC, Franklin N. Early initiation of and exclusive breastfeeding in large-scale community-based programmes in Bolivia and Madagascar. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):530–9.

Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e380–6.

World Health Organization. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. WHO collaborative study team on the role of breastfeeding on the prevention of infant mortality. Lancet. 2000;355(9202):451–5.

Setegn T, Gerbaba M, Belachew T. Determinants of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers in Goba Woreda, South East Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:217.

Ogbo FA, Page A, Idoko J, Claudio F, Agho KE. Diarrhoea and suboptimal feeding practices in nigeria: evidence from the national household surveys. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(4):346–55.

Mekonnen Y, Tensou B, Telake DS, Degefie T, Bekele A. Neonatal mortality in Ethiopia: trends and determinants. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:483.

Dearden K, Altaye M, Maza ID, Oliva MD, Stone-Jimenez M, Morrow AL, Burkhalte BR. Determinants of optimal breast-feeding in peri-urban Guatemala City, Guatemala. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;12(3):185–92.

Flacking R, Nyqvist KH, Ewald U. Effects of socioeconomic status on breastfeeding duration in mothers of preterm and term infants. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(6):579–84.

Morhason-Bello IO, Adedokun BO, Ojengbede OA. Social support during childbirth as a catalyst for early breastfeeding initiation for first-time Nigerian mothers. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4:16.

Tarrant RC, Kearney JM. Session 1: public health nutrition Breast-feeding practices in Ireland. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(4):371–80.

Horii N, Guyon AB, Quinn VJ. Determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding in rural Ethiopia: programmatic implications. Food Nutr Bull. 2011;32(2):94–102.

Dhandapany G, Bethou A, Arunagirinathan A, Ananthakrishnan S. Antenatal counseling on breastfeeding–is it adequate? A descriptive study from Pondicherry, India. Int Breastfeed J. 2008;3:5.

Chudasama RK, Amin CD, Parikh YN. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and its determinants in first 6 months of life: a prospective study. Online Journal of Health and Allied Sciences. 2009;8:1.

Miller NP, Amouzou A, Tafesse M, Hazel E, Legesse H, Degefie T, Victora CG, Black RE, Bryce J. Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: implementation strength and quality of care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(2):424–34.

Labbok MH. Global baby-friendly hospital initiative monitoring data: update and discussion. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:210–22.

Wikipedia. Dale (woreda). 2015; Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dale_(woreda). Accessed 8 Oct 2016.

Berde AS, Yalcin SS. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria: a population-based study using the 2013 demograhic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:32.

Hailemariam TW, Adeba E, Sufa A. Predictors of early breastfeeding initiation among mothers of children under 24 months of age in rural part of West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1076.

Gultie T, Sebsibie G. Determinants of suboptimal breastfeeding practice in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:5.

Ersino G, Henry CJ, Zello GA. Suboptimal feeding practices and high levels of undernutrition among infants and young children in the rural communities of Halaba and Zeway. Ethiopia Food Nutr Bull. 2016;37(3):409–24.

Jennifer HG, Muthukumar K. A cross-sectional descriptive study was to estimate the prevalence of the early initiation of and exclusive breast feeding in the rural health training centre of a medical college in Tamilnadu, South India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(9):1514–7.

Colombara DV, Hernández B, Gagnier MC, Johanns C, Desai SS, Haakenstad A, McNellan CR, Palmisano EB, Ríos-Zertuche D, Schaefer A, Zúñiga-Brenes P. Breastfeeding practices among poor women in Mesoamerica. J Nutr. 2015;145(8):1958–65.

Sharma IK, Byrne A. Early initiation of breastfeeding: a systematic literature review of factors and barriers in South Asia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:17.

Acknowledgment

Our gratitude goes to Addis Ababa University, centralized school of nursing and midwifery for approving and funding this research. We would also thank Fekadu Aga, Balew Arega, Amha Admasse for their valuable comments. Lastly, we extend our recognition to all Dale Woreda health extension workers, data collectors, supervisors, study participants and all our friends who supported us to accomplish this study.

Funding

Addis Ababa University funded this research. However, there was no funding for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The article included all relevant data.

Authors’ contributions

MG, NR, and ZM conceived and designed the study. MG and TD analyzed the data and drafting of the manuscript. All the authors read the manuscript several times and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ information

Misrak Getnet Beyene (MG) (Master of science in Maternal and Reproductive Health Nursing, Master of Public Health, Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Ethiopia.

Dr. Nigatu Regassa Geda (NR) (Associate Professor, Ph.D., Former Vice President for Business and Development, Hawassa University and a Visiting Scholar at University of Saskatchwan Canada, Ethiopia.

Tesfa Dejenie Habtewold (TD) (Master of Science in Adult Health Nursing, Master of Science in (Clinical and Psychosocial) Epidemiology, University of Groningen, Department of Epidemiology, the Netherlands.

Zuriash Mengistu Assen (ZM) (Master of Nursing, Ph.D. in Public Health, Addis Ababa University, Centralized School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ethiopia.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Addis Ababa University, Centralized School of Nursing and Midwifery, Institutional Review Board provided ethical clearance. Official permission was obtained from zonal and Woreda administrative office to make all necessary arrangements. At the time of data collection, the purpose of the study was explained and written consent was obtained from each mother. Confidentiality of the data was maintained by excluding names as identification in the questionnaire and keeping their privacy during the interview.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Questionnaire. (DOCX 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Beyene, M.G., Geda, N.R., Habtewold, T.D. et al. Early initiation of breastfeeding among mothers of children under the age of 24 months in Southern Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J 12, 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-016-0096-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-016-0096-3