Abstract

Background

Second victims, defined as healthcare team members being traumatised by an unanticipated clinical event or outcome, are frequent in healthcare. Evidence of this phenomenon in Germany, however, is sparse. Recently, we reported the first construction and validation of a German questionnaire. This study aimed to understand this phenomenon better in a sample of young (<= 35 years) German physicians.

Methods

The electronic questionnaire (SeViD-I survey) was administered for 6 weeks to a sample of young physicians in training for internal medicine or a subspecialty. All physicians were members of the German Society of Internal Medicine. The questionnaire had three domains - general experience, symptoms, and support strategies - comprising 46 items. Binary logistic regression models were applied to study the influence of various independent factors on the risk of becoming a second victim, the magnitude of symptoms and the time to self-perceived recovery.

Results

The response rate was 18% (555/3047). 65% of the participants were female, the mean age was 32 years. 59% experienced second victim incidents in their career so far and 35% during the past 12 months. Events with patient harm and unexpected patient deaths or suicides were the most frequent key incidents. 12% of the participants reported that their self-perceived time to full recovery was more than 1 year or have never recovered. Being female was a risk factor for being a second victim (odds ratio (OR) 2.5) and experiencing a high symptom load (OR 2). Working in acute care was promoting a shorter duration to self-perceived recovery (OR 0.5). Support measures with an exceptionally high approval among second victims were the possibility to discuss emotional and ethical issues, prompt debriefing/crisis intervention after the incident and a safe opportunity to contribute insights to prevent similar events in the future.

Conclusion

The second victim phenomenon is frequent among young German physicians in internal medicine. In general, these traumatic events have a potentially high impact on physician health and the care they deliver. A better understanding of second victim traumatisations in Germany and broad implementation of effective support programs are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Healthcare is associated with relevant risks not only for patients, but also for healthcare professionals [1]. Besides well-known risks to physical integrity like needle stick injuries [2] or psychological stress [1, 3, 4], unanticipated clinical events or outcomes (often caused by mistakes in healthcare) do not only harm patients. They also traumatise healthcare professionals, who may thus become so-called second victims [5, 6]. Being a second victim may lead to dysfunctional coping strategies [7], resulting in a change in work behaviour and leading to further negative employee-related outcomes. These outcomes are psychological and psychosomatic symptoms [8], including isolation, reduced quality of life up to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [7, 9, 10], or even suicide [11]. Furthermore, the care of future patients (i.e., practising defensive medicine [12, 13]) can be negatively affected, leading to overall reduced quality of care [14]. Previous surveys in English-speaking countries indicate prevalences up to 42% of second victims among healthcare professionals [15, 16]. Based on the research of the natural history of second victim traumatisation [5], several interventional programs for healthcare professionals were launched, mainly in English-speaking countries [17, 18]. They showed beneficial evidence regarding employee-related outcomes [17, 19], and cost-effectiveness [20].

In Germany, the association of statutory accident insurances defined standards for employees’ care after traumatising events [21]. The first recommendation regarding handling of traumatisations after severe complications in patient care was published in 2013 by the German Society and the German Association of Anaesthesiologists [22]. Contrary to sectors like rail services [23] or air traffic [24], where psychological support for employees after traumatising events has been addressed already, no systematic assessment of this phenomenon in the German-speaking healthcare sector has been published so far.

For this reason, we initiated the SeViD (Second Victims im Deutschsprachigen Raum/Second Victims in German-speaking Countries) project. As a first step, we developed and validated a German-language questionnaire for the assessment of second victim incidents [25].

This study describes the new questionnaire’s first application in a sample of young German physicians, who are in training for general internal medicine or an internal medicine subspecialty. This research was planned and conducted before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nevertheless, the pandemic is an example, how an unanticipated adverse event can put many healthcare professionals under extreme pressure. Specialists experience high workloads and deal with uncertainty and death while at risk of contracting the illness themselves.

This study aims at adding evidence to the second victim phenomenon by evaluating the following hypotheses:

-

The prevalence of second victims among young physicians being trained in internal medicine in Germany is different from reported prevalences from other countries, specialties and age groups.

-

Distinct factors can predict the risk of becoming a second victim, the magnitude of symptoms and the time to self-perceived recovery after traumatic events.

-

Second victims favour certain support strategies.

Methods

Construction and validation of the SeViD questionnaire

The detailed construction and validation of the questionnaire is described in our recent article [25]. Since the original publication is the German language, we provide a brief description: A systematic literature search identified existing questionnaires evaluating the second victim phenomenon in healthcare. Based on these sources (six questionnaires from nine resources), a new German-language questionnaire was developed and tailored to our previously established needs in terms of brevity, straightforward applicability to different groups of healthcare professionals in European healthcare systems and covering broad aspects of the second victims phenomenon (prevalence, symptoms and support strategies). The preliminary version of this questionnaire was subject to cognitive pre-testing in order to ensure content validity. We included healthcare professionals of different professional groups with or without previous second victim experience to participate as volunteers for all pre-tests after informed consent. An independent researcher conducted all cognitive pre-tests. The final questionnaire consists of three domains and 40 items (Table 1). For the symptoms domain, participants answered by a 3-point (strongly pronounced, weakly pronounced, not pronounced) and for the support strategies domain by a 4-point (very helpful, rather helpful, rather not helpful and not helpful) ordinal scale. The options “Don’t know” and “I cannot judge this”, respectively, were also included.

Design and conduction of the SeViD-I survey

Reporting of this survey is following the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys [26]. The survey was conducted using the commercial application SurveyMonkey® (San Mateo, California, US). The electronic survey was embedded in the official homepage of the German Society of Internal Medicine (DGIM e.V.). An invitation with a link for participation was sent by the society itself to all members in training for general internal medicine or an internal medicine subspecialty, being no more than 35 years of age and working in a hospital (n = 3047). A reminder was sent after two and 4 weeks and the survey was closed after 6 weeks. The study period ranged from the 20th of August to the 1st of October 2019. Beforehand, the local regulation authority confirmed that no official ethical approval was mandatory. Data collection was completely anonymised with neither tokens or cookies, nor IP addresses stored. The survey was distributed on six panels. The invitation and the reminder for participation included statements on the purpose of the survey, explanation of the term “second victim”, information on responsible investigators (including a contact email address in case of questions) information on the anonymisation process, length of the study, voluntary participation and data protection. The survey was not communicated outside the above-mentioned sample and was only accessible with the provided link. Because of complete anonymisation, a potential multiple participation and spread of the invitation link to others outside the sample could not be controlled. Six items assessing baseline characteristics (gender, age, years in training, specialty status, time in hospital during last 12 months, principal workplace in a hospital during last 12 months) were added to the SeViD questionnaire described above. The survey used adaptive questioning (e.g. questions of the symptoms domain only to participants who had experienced second victim incidents). Each question had to be answered before moving to the next. Participants were able to move back to change their answers. After completion of the survey, participants could voluntarily register via a separate email address for a raffle of incentives (book vouchers and free access to a DGIM training course). All available data were analysed for each question with each number of data points indicated in the results section.

Preparation and re-coding of variables for statistical analysis

The continuous variables - age and time in specialty training - were categorised (25–30, 31–32 and 33–36 years of age and 1–3, 4–5 and 6–13 years in training, respectively). The item asking for the principal place of work in a hospital was dichotomised into working predominantly in acute care (intensive/ intermediate care and/or emergency department) versus others. Other dichotomisations were performed for the second victim status (before three categories), having experienced support (before three categories) and time to self-perceived full recovery after the key incident (1 month or less vs. more than 1 month). For estimation of the participants’ symptom load, a sum score was calculated based on the answers to the 20 items of this domain. Answers “strongly pronounced” were counted as 1 and “weakly pronounced” as 0.5 (“not at all” and “don’t know” as 0). After this a sum score for each participant was calculated. Based on the median (which was 8.5) this new variable was dichotomised for establishing a low and high symptom load group.

Statistics

As parametric methods for statistical hypothesis testing, the t-test for independent samples (with 95% confidence interval) was used to compare two groups. Expected and observed distribution patterns were compared using contingency tables and analysed for statistical significance applying the Chi2 test. The influence of independent variables (gender, age, years in training, specialty status, workplace, support and symptoms; different combinations of variables for each model) on dependent variables (a second victim status, symptom load and time to self-perceived recovery) were assessed using binary logistic regression models. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics Version 26 (IBM, New York).

Results

Response rate, non-responder analysis and baseline characteristics

The mean duration of completion for the questionnaire was 5 min and 1 s. From 3047 invited members of the society 555 took part in this survey. This leads to a response rate of 18% (555/3047). At the end of the first questionnaire domain 21 participants (4%) had left the survey. Four hundred ninety-one participants completed the whole questionnaire (88%). Comparing the target to the study population, more women (59% (1799/3047) vs. 65% (361/555); p = 0.01, Chi2) and slightly younger participants (mean age ± standard deviation: 31,8 ± 2,2 vs. 31,6 ± 2,2; p = 0.04, t-test) took part in this survey. The prevalence of second victims did not vary over the three study periods between invitation and two reminders (p = 0.45, Chi2). Four participants were 36 years of age (these participants turned 36 after the sample was drawn and before they participated in the survey; these cases were included in the final analyses). The median duration of training was 4 years (mean duration 4.5 ± 1.8 years; n = 555). Of physicians being six or more years in training, 52% (68/130) have successfully achieved a first formal specialty degree. In Germany 5 years is the minimum duration to achieve the general internal medicine specialty degree followed by optional additional 3 years for an internal medicine subspecialty; alternatively, an internal medicine subspecialty degree can be obtained directly after a minimum of 6 years. The mean time in patient care during the last 12 months was 10.5 ± 2.9 (median 12) months among the participants (n = 541; main reasons for time off are parental leave or research activities). 63% (342/541) predominantly worked on general wards, 24% (128/541) on intermediate or intensive care units, 14% (73/541) in the emergency department, 7% (35/541) performing interventions and other 7% (35/541) working in an outpatient clinic (cumulative percent > 100 because multiple answers were accepted).

Second victim incidents

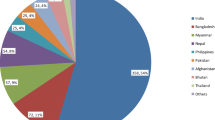

While 90% (481/534) of the participants had no knowledge of the term “second victim” before invitation to this survey, 59% (314/534) of the participants have experienced a second victim incident before (Fig. 1); from these, 27% (141/534) once and 32% (173/534) several times. 61% (190/310) of second victims experienced at least one incident during the last 12 months. This translates to an overall 12-months prevalence of 35%.

The types of key incidents and self-perceived time until full recovery are displayed in Table 2. Incidents with patient harm (34% (106/310)) and unexpected deaths or suicides of patients (35% (108/310)) were reported as the most frequent key events. Self-perceived time to full recovery after the key event was reported as up to 1 month by 72% (206/287) and as more than 1 month by 28% (81/287) of the participants. 49% (152/310) of the participants received support overcoming the incident from others. 15% (45/310) did not get support, although they asked for it, and other 36% (113/310) did not ask for support. Support came (selection of multiple sources possible) in 82% (117/142) from colleagues, in 60% (84/142) from friends and relatives, in 42% (60/142) from superiors, in 4% (5/142) from professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists) and in 1% (1/142) from the administration.

Risks factors for being a second victim

Based on a binary logistic regression model the influence of the independent variables gender, age, years in training, specialty status and working predominantly in acute care on being a second victim was analysed (n = 534; Table 3). This model’s risk factor with an odds ratio of 2.5 (95%-CI 1.70–3.55, p < 0.01) was female sex. Another risk factor was advanced years in training (6 or more years) with an odds ratio of 2 (95%-CI 1.01–4.23, p = 0.046).

Factors with impact on the symptom load of second victims

Based on a binary logistic regression model the influence of the independent variables gender, age, years in training, specialty status and working predominantly in acute care on the symptom load of second victims was analysed (n = 314; Table 4). The only risk factor for a high symptom load found in this model with an odds ratio of 2 (95%-CI 1.18–3.36, p = 0.01) was female sex.

Factors with impact on the time to self-perceived full recovery after the key incident

In a third binary logistic regression model the influence of the independent variables gender, age, years in training, specialty status, working predominantly in acute care, having experienced support and a categorised symptom score on the self-perceived time to full recovery (1 month or less versus more than 1 month) of second victims was analysed (n = 286; Table 5). The only statistically significantly associated factor was working in acute care with an odds ratio of 0.5 (95%-CI 0.28–0.94, p = 0.03), thus promoting a shorter duration to self-perceived full recovery.

Support strategies for second victims

The participants (n = 491) were asked to rate 13 established support strategies for second victims (options were “very helpful”, “rather helpful”, “rather not helpful”, “not helpful” and “I cannot judge this”, Table 6). Support measures rated by > 90% of the second victims as very or rather helpful were the possibility to discuss emotional and ethical issues (93%, 265/287), prompt debriefing/crisis intervention after the incident (95%, 271/287) and a safe opportunity to contribute insights to prevent similar events in the future (92%, 265/287). The ratings of support strategies by second victims versus others were tested for unequal distributions (Chi2 tests; 4-point Likert scale). Statistically significant differences were observed for strategy 2 “access to counselling including psychological/psychiatric services” (81% vs. 88% rated rather or very helpful; p < 0.01), 11 “help to actively participate to work through this incident” (87% vs. 82% rated rather or very helpful; p = 0.02) and 13 “opportunity to seek for legal advice after an incident” (86% vs. 95% rated rather or very helpful; p = 0.04).

Discussion

The survey aimed to investigate the prevalence, influencing factors on occurrence and course as well as support strategies for second victim traumatisations in a cross-sectional fashion among young German physicians working in internal medicine in inpatient care. International studies, especially from the US, suggest [16] that second victim traumatisations are frequent among healthcare professionals and potentially carry a high impact on affected and future patients, the professionals themselves, their colleagues and thus the whole healthcare system. Data from Germany is scarce, which implies a considerable need for more research and campaigns in this country.

Nine out of ten participants of this survey had no knowledge of the term “second victim”. That does not automatically imply that these physicians were unaware of potentially occurring traumatisations at work, but the tendency seems obvious. In contrast, the study of Edrees et al. reported in 2011 that 46% (n = 139 participants, manly nurses from Johns Hopkins University/ US) were aware of the term second victim and its definition [27]. One reason could be that healthcare professionals’ traumatisations are until today, to our knowledge, neither mentioned in German medical school or specialty training curricula, nor many support programs exist at German hospitals and medical universities. In 2016, the European Board of Internal Medicine published European standards of postgraduate medical specialist training [28]. Even this modern and comprehensive curriculum addresses traumatisations of healthcare professionals only superficially within the so-called milestones belonging to the CanMEDS framework (e.g. one milestone of the role healthcare advocate “identify, reflect on, and learn from critical incidents such as near misses and preventable medical errors” or one milestone of the role professional “recognise and address personal, psychological, and physical limitations that may affect performance”). Another limitation might be that until today parallel definitions of the term second victims exist (for three frequent definitions, see [16]). In this context, it should be mentioned that the term second victim is criticised by some experts, who argue that it diminishes the importance and seriousness of the injury or complication of the patient and affected relatives [29].

The prevalence of single or multiple second victim traumatisations found in our study among young Germany physicians in internal medicine was high (59% all-over), with 35% of the physicians affected in the last 12 months. A review [16] reported prevalence rates from three studies varying from 10 to 43.3%: A study from Lander et al. from 2006 among otolaryngologists reported a 6-month prevalence of 10% [30], whereas the study of Scott et al. from 2010 among various healthcare professionals including students found a 12-month prevalence of 30% [18] and, finally, the study by Wolf and colleagues from 2000 described the prevalence of 43.1% again among various healthcare professionals [31]. These studies mostly included older populations from different specialties in the United States. Compared to the results of this study, there is no clear signal that prevalences vary substantially with these factors.

Most traumatising incidents from this study where related to situations with direct harm to a patient or even their death. A minor number of cases were near misses or aggressive patients or their relatives. Remarkably, Waterman et al. in a study from 2007 stated that a third of the physicians who “only” have been involved in near misses were suffering from typical second victim traumatisations as well [7].

Most second victims recover soon after traumatising events. Nevertheless, a small but relevant proportion - in our study 12% who need more than 1 year or have not recovered so far - recover late or never. Gazoni et al. report that 19% of traumatised anaesthesiologists have never fully recovered [32]. Especially these colleagues need early and effective help to reduce the risk for severe outcomes like dysfunctional coping strategies, which potentially could harm other patients [7], lead to physical and psychological morbidity [16], or could lead to leaving the profession [19].

Logistic regression models in of our study suggest that women are at greater risk of becoming a second victim (OR 2.5) and having higher symptom loads (OR 2) than men. Besides methodical limitations (e.g. women were overrepresented in the study sample) published studies reported several gender-related differences regarding the second victim phenomenon. Tolin and Foa conclude in a quantitative review from 2006 that females are generally more likely to meet PTSD criteria than men. However, they are less likely to experience potentially traumatic events [33]. Studies by Kaldjian et al. [34], Muller and Ornstein [35] and Wu et al. [36] report more distress among women after traumatising events on one side (e.g. feeling more guilt, being more afraid of losing confidence or reputation), but more constructive patterns of handling the situation compared to men on the other side (e.g. more motivated to discuss errors or to support changes in practice).

In our study, being in advanced training stages (6 years and more) was associated with a higher risk of becoming a second victim (OR 2). In a study by West et al. [15], the prevalence of second victims increased with time from a 3-months prevalence of 14.3% to a 3-years prevalence of 34%. Some authors argue that almost every healthcare professional will experience at least one traumatic event throughout their career [9].

In this study, shorter duration until self-perceived full recovery after a traumatic event was associated with predominantly working in acute care (OR 0.5). An explaining hypothesis could be that adverse events happen more frequently in these fields, so physicians might be better prepared through more routine and expectancy in dealing with such situations.

All regression models show a deficiency in predicting the outcome of the dependent variable. The possible explanation is that the relevant factors have not been included in these models and/or that multiple factors and their complex interactions influence the outcome. Van Gerven et al. lists personal, situational and organisational aspects that impact the outcome [37]. Therefore, further research could concentrate on individual factors like personality characteristics, details of the traumatising events, or environmental conditions to explain differences.

Second victims of this study report that support in overcoming the traumatising event originated mainly from colleagues and friends or relatives, namely from the closest surrounding persons at work and home. Furthermore, second victims ask in particular for support strategies which include a prompt debriefing with discussion of the event and related emotional/ ethical aspects.

Today, nationwide support programs do not exist in the US [5, 7, 38] nor in Europe [39,40,41]. Single programs have been developed (e.g. in the US: “Medically Induced Trauma Support Service (MITTS)” in Boston [42], the “forYOU” program at the University of Missouri Health Care [18] or the „Resilience in Stressful Events (RISE)” program at Johns Hopkins Hospital [17] and in Europe: “PSUakut”, which is a support program for healthcare professionals working in acute care in Germany [43], the “Mitigating Impact in Second Victims (MISE)” online support program in Spain [40] or “Collegial Help (Kollegiale Hilfe/ KoHi)”, a support program for second victims which is currently established at the Hietzing hospital in Vienna/ Austria [44]). All programs include graduated levels of support. Scott et al. for example describe the following three levels (three tiers): Tier 1 with local unit/department support by direct colleagues, tier 2 with support through trained peer supporters and tier 3 with support through an established referral network (including professional support up to psychologists). The authors estimate that on these levels 60, 30 and 10%, respectively, of all second victims will receive sufficient support. Our study shows that most traumatised physicians who received support get it from their colleagues or friends. According to the just mentioned estimations by Scott et al., up to 40% might not receive the right support they need if professional support programs are not in place.

All support programs for second victims and their prevention aim for strengthening the resilience of healthcare professionals. The term “resilience” has been significantly shaped by the work of Aaron Antonovsky. He defined the sense of coherence as a prerequisite for resilience that is based on three components: viewing the world as comprehensible, meaningful and manageable. Regarding the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and drawing on current recommendations by Wu et al. we recently published recommendations for healthcare leadership which take these three above-mentioned components into account [45].

Our findings may be limited in several important ways. The cross-sectional design can describe associations but will never link causation. Our sample of young physicians in internal medicine was a convenience sample that is liable to selection bias and thus might lack representativity. More physicians with traumatic incidents in their past could have taken advantage of the survey. More women than expected were among our study participants. Furthermore, investigating only members of one medical society could harbour bias because members could have specific characteristics that might distinguish them from others. Another limitation is the low response rate and the number of dropouts which increased with the duration of the survey (at the last questions around 11%). The fear of potential participants to admit that something went wrong could have negatively influenced the response rate. There is often still a culture of blame in the workplace and fear of recrimination. Furthermore, due to the anonymous conduction of the survey we cannot exclude multiple participations of certain participants. Nevertheless, study characteristics like the response or dropout rates of our electronic survey were among expected limits for such designs. The item “time to full recovery” is difficult to define. Participants might feel that they have fully recovered, but the traumatic incident could still influence their behavior. Additionally, recovery might be a process with ups and downs. Finally, we did not correct for multiple-hypothesis testing. Our analysis is mainly explorative and is supposed to generate hypotheses and a basis for further research in Germany and Europe. Thus, we leave space in drawing the line between statistical significance and clinical relevance to the reader.

Conclusions

This study describes a high prevalence of second victim traumatisations among young physicians in internal medicine in Germany for the first time. Furthermore, characteristics of these traumatisations have been analysed and support strategies have been evaluated. However, this should be the beginning. There is an obvious need for more research in this field in Germany. It would for example be desirable to understand which environmental conditions and which personality characteristics facilitate traumatisations and lead to worse outcomes. This might help to tailor primary prevention measures and support programs. Establishing nationwide effective support structures for our patients, colleagues and ourselves is our social, ethical and organisational responsibility.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DGIM:

-

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin (German Society of Internal Medicine)

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MISE:

-

Mitigating Impact in Second Victims

- MITTS:

-

Medically Induced Trauma Support Service

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PSUakut:

-

Psychosoziale Unterstützung akut (acute psychosocial support)

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2

- SeViD:

-

Second victims in Deutschland (Germany)

- RISE:

-

Resilience in Stressful Events

References

Richarz S. Psychische Belastung in der Gefährdungsbeurteilung. Zentralblatt für Arbeitsmedizin, Arbeitsschutz und Ergonomie. 2018;68(6):334–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40664-018-0290-9.

Bouya S, Balouchi A, Rafiemanesh H, Amirshahi M, Dastres M, Moghadam MP, Behnamfar N, Shyeback M, Badakhsh M, Allahyari J, al Mawali A, Ebadi A, Dezhkam A, Daley KA. Global prevalence and device related causes of needle stick injuries among health care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86(1):35. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2698.

Koch P, Zilezinski M, Schulte K, Strametz R, Nienhaus A, Raspe M. How perceived quality of care and job satisfaction are associated with intention to leave the profession in young nurses and physicians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082714.

Kersten M, Kozak A, Wendeler D, Paderow L, Nubling M, Nienhaus A. Psychological stress and strain on employees in dialysis facilities: a cross-sectional study with the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2014;9(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-9-4.

Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.032870.

Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.726.

Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, Dunagan WC, Levinson W, Fraser VJ, Gallagher TH. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(07)33050-X.

Busch IM, Moretti F, Purgato M, Barbui C, Wu AW, Rimondini M. Psychological and psychosomatic symptoms of second victims of adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(2):e61–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000589.

Laue N, Schwappach D, Hochreutener M. “Second victim” - Umgang mit der Krise nach dem Fehler. Ther Umsch Rev Ther. 2012;69(6):367–70.

Schwappach DL, Boluarte TA. The emotional impact of medical error involvement on physicians: a call for leadership and organisational accountability. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(1–2):9–15.

Grissinger M. Too many abandon the “second victims” of medical errors. P T. 2014;39(9):591–2.

Panella M, Rinaldi C, Leigheb F, Donnarumma C, Kul S, Vanhaecht K, di Stanislao F. The determinants of defensive medicine in Italian hospitals: the impact of being a second victim. Rev Calid Asist. 2016;31(Suppl 2):20–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cali.2016.04.010.

Pyo J, Choi EY, Lee W, Jang SG, Park YK, Ock M, Lee SI. Physicians’ difficulties due to patient safety incidents in Korea: a cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(17):e118. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e118.

Vincent C, Amalberti R. Safer Healthcare: Strategies for the Real World. Cham (CH) 2016. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319255576.

West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, Shanafelt TD. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1071–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1071.

Seys D, Wu AW, van Gerven E, Vleugels A, Euwema M, Panella M, et al. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36(2):135–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278712458918.

Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, Norvell M, Taylor H, Wu AW. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011708. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011708.

Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Hahn-Cover K, Epperly KM, Phillips EC, Hall LW. Caring for our own: deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(5):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(10)36038-7.

Burlison JD, Quillivan RR, Scott SD, Johnson S, Hoffman JM. The effects of the second victim phenomenon on work-related outcomes: connecting self-reported caregiver distress to turnover intentions and absenteeism. J Patient Saf. 2016;Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000301.

Moran D, Wu AW, Connors C, Chappidi MR, Sreedhara SK, Selter JH, Padula WV. Cost-benefit analysis of a Support Program for Nursing Staff. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(4):e250–e254. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000376.

Spitzenverband der Deutschen Gesetzlichen Unfallversicherung. DGUV Information 206–023: Standards in der betrieblichen psychologischen Erstbetreuung (bpE) bei traumatischen Ereignissen. 2017. https://publikationen.dguv.de/widgets/pdf/download/article/3227. Accessed 7 Mar 2021.

DGAI. Kommission Berufliche Belastung der DGA. Umgang mit schweren Behandlungskomplikationen und belastenden Verläufen. Anästh Intensivmed. 2013;54:490–4.

European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/796 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on the European Union Agency for Railways and repealing Regulation (EC) no 881/2004. 2016. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0796. Accessed 7 Mar 2021.

European Union. Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2018 on common rules in the field of civil aviation and establishing a European Union Aviation Safety Agency, and amending Regulations (EC) No 2111/2005, (EC) No 1008/2008, (EU) No 996/2010, (EU) No 376/2014 and Directives 2014/30/EU and 2014/53/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Regulations (EC) No 552/2004 and (EC) No 216/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Council Regulation (EEC) No 3922/91. 2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32018R1139. Accessed 7 Mar 2021.

Strametz R, Roesner H, Abloescher M, Huf W, Ettl B, Raspe M. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess incidence and reactions of second victims in German speaking countries (SeViD). Zbl Arbeitsmed. 2021;71(1):19–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40664-020-00400-y.

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34.

Edrees HH, Paine LA, Feroli ER, Wu AW. Health care workers as second victims of medical errors. Polish Arch Internal Med. 2011;121(4):101–8. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.1033.

European Board of Internal Medicine (EBIM). Training Requirements for the Specialty of Internal Medicine - European Standards of Postgraduate Medical Specialist Training. 2016. http://efim.org/system/files/downloads/efim_eu_curriculum.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2021.

Clarkson MD, Haskell H, Hemmelgarn C, Skolnik PJ. Abandon the term “second victim”. BMJ. 2019;364:l1233.

Lander LI, Connor JA, Shah RK, Kentala E, Healy GB, Roberson DW. Otolaryngologists’ responses to errors and adverse events. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):1114–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000224493.81115.57.

Wolf ZR, Serembus JF, Smetzer J, Cohen H, Cohen M. Responses and concerns of healthcare providers to medication errors. Clin Nurse Spec. 2000;14(6):278–87; quiz 88-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002800-200011000-00011.

Gazoni FM, Amato PE, Malik ZM, Durieux ME. The impact of perioperative catastrophes on anesthesiologists: results of a national survey. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(3):596–603. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318227524e.

Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):959–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959.

Kaldjian LC, Forman-Hoffman VL, Jones EW, Wu BJ, Levi BH, Rosenthal GE. Do faculty and resident physicians discuss their medical errors? J Med Ethics. 2008;34(10):717–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2007.023713.

Muller D, Ornstein K. Perceptions of and attitudes towards medical errors among medical trainees. Med Educ. 2007;41(7):645–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02784.x.

Wu AW, Folkman S, McPhee SJ, Lo B. Do house officers learn from their mistakes? JAMA. 1991;265(16):2089–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1991.03460160067031.

Van Gerven E, Deweer D, Scott SD, Panella M, Euwema M, Sermeus W, et al. Personal, situational and organizational aspects that influence the impact of patient safety incidents: a qualitative study. Rev Calid Asist. 2016;31(Suppl 2):34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cali.2016.02.003.

Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. West J Med. 2000;172(6):358–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/ewjm.172.6.358.

Ullström S, Andreen Sachs M, Hansson J, Ovretveit J, Brommels M. Suffering in silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):325–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002035.

Mira JJ, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Lorenzo S, Perez-Perez P, Silvestre C, et al. The second victim phenomenon after a clinical error: the design and evaluation of a website to reduce caregivers’ emotional responses after a clinical error. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(6):e203. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7840.

Rinaldi C, Leigheb F, Vanhaecht K, Donnarumma C, Panella M. Becoming a “second victim” in health care: pathway of recovery after adverse event. Rev Calid Asist. 2016;31(Suppl 2):11–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cali.2016.05.001.

Pratt S, Kenney L, Scott SD, Wu AW. How to develop a second victim support program: a toolkit for health care organizations. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(5):235–40, 193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(12)38030-6.

Hinzmann D, Schießl A, Koll-Krüsmann M, Schneider G, Kreitlow J. Peer-Support in der Akutmedizin. Anästh Intensivmed. 2019;60:95–101.

Abloescher M. Kollegiale Hilfe (KoHi) - Psychische Erste Hilfe durch KollegInnen im KHR. 2019. https://www.plattformpatientensicherheit.at/download/APSA-2019/einreichungen/Kurzbeschreibung_Abloescher.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2021.

Strametz R, Raspe M, Ettl B, Huf W, Pitz A. Handlungsempfehlung: Stärkung der Resilienz von Behandelnden und Umgang mit Second Victims im Rahmen der COVID-19-Pandemie zur Sicherung der Leistungsfähigkeit des Gesundheitswesens [Recommended actions: Reinforcing clinicians’ resilience and supporting second victims during the COVID-19 pandemic to maintain capacity in the healthcare system] [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 2]. Zentralbl Arbeitsmed Arbeitsschutz Ergon. 2020;1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40664-020-00405-7.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the German Society for Internal Medicine (DGIM e.V.) and their members for support and participation. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS, PK, AV, AB, HR, MA, WH, BE and MR were responsible for conceptualisation and planning of this study. RS, PK and MR were conducting the statistical analyses. RS ad MR prepared the original draft. RS, PK, AV, AB, HR, MA, WH, BE and MR reviewed and edited the draft. RS and MR supervised and coordinated the work on this project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Because of the research design, no formal vote of the Ethics Committee was required. This was confirmed by the head of the local ethics committee (ethics committee of the state medical association of Hesse) in response to an informal request beforehand. To ensure data protection, all data were collected without any demographic information that would allow the participants’ identification. All participants gave their consent to the use of data for this study.

Consent for publication

All participants were informed about the study and gave their consent to the publication of survey data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Strametz, R., Koch, P., Vogelgesang, A. et al. Prevalence of second victims, risk factors and support strategies among young German physicians in internal medicine (SeViD-I survey). J Occup Med Toxicol 16, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-021-00300-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-021-00300-8