Abstract

Background

Compared to the general population, physicians are more likely to experience increased burnout and lowered work-life balance. In our article, we want to analyze whether the workplace of a physician is associated with these outcomes.

Methods

In September 2019, physicians from various specialties answered a comprehensive questionnaire. We analyzed a subsample of 183 internists that were working full time, 51.4% were female.

Results

Multivariate analysis showed that internists working in an outpatient setting exhibit significantly higher WLB and more favorable scores on all three burnout dimensions. In the regression analysis, hospital-based physicians exhibited higher exhaustion, cynicism and total burnout score as well as lower WLB.

Conclusions

Physician working at hospitals exhibit less favorable outcomes compared to their colleagues in outpatient settings. This could be a consequence of workplace-specific factors that could be targeted by interventions to improve physician mental health and subsequent patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physicians have a higher risk of both increased burnout and lowered work-life balance (WLB) as compared to the general population [1, 2]. Burnout can be a consequence of chronic workplace stress and it is characterized by feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and a decrease in professional efficacy [3]. Consequently, burnout is often understood as a three-dimensional construct, consisting of exhaustion, cynicism and (reduced) professional efficacy [4], and it is often connected to unfavorable WLB [5,6,7].

Due to physicians` position in the health system, their working situation and mental health have implications for the population. Research shows that physicians` WLB and burnout are connected to medical errors [8,9,10]. In addition, physician burnout is associated with reductions in professional work effort, increased risk of patient safety incidents, lower quality of care, and reduced patient satisfaction [11,12,13]. Han et al. [14] conservatively estimate that approximately 4.6 billion USD related to physician turnover and reduced clinical hours can be attributed to burnout each year in the United States.

The majority of physicians worldwide either work in hospitals or practices, and both work places differ in many ways, e.g., with regard to autonomy, work tasks, or responsibility. In their meta-analysis, Roberts et al. [15] found that outpatient-based physicians reported more exhaustion than their inpatient-based colleagues. In their comparative national study the authors showed that physicians in hospitals were more likely to score low on personal accomplishment, a scale similar to professional efficacy, and that they were also more likely to agree that their work schedule leaves enough time for their personal life and family [16]. The study reflects the situation in the US, the meta-analysis includes research from different nations like Hungary [17], Argentina [18] or Australia [19]. Since national health systems, regulations, and financing fundamentally impact working conditions of physicians, results from one country cannot easily be assumed to be valid in another context. Hence, with this study we want to fill a gap in the literature and analyze in how far physicians` workplaces – hospital vs. practice – are associated with burnout and WLB. Our focus is on internists, since they work in inpatient as well as outpatient settings.

Methods

Study design and sample

In September 2019, 25% of physicians working in the Federal State of Saxonia, a region in the Eastern part of Germany, were randomly selected and asked to fill out a questionnaire on work strain, health, and work satisfaction, resulting in a sample of 1412 physicians from different specialties. For the analysis in this article we included a subsample of specialists in internal medicine working full time, either in a hospital or in a practice. After removing 67 participants due to missing values, the sample for analysis contained 183 persons.

Assessment

We assessed whether physicians worked in a practice or at a hospital. In addition, sociodemographic data including age (in years), gender, marital status, and children living in the household (yes vs. no) were assessed. In Germany, physicians working full time at hospitals with few exceptions have similar work contracts with around 42 h per week and little variation in wages (collective agreement). Physicians in their own practices are freelancers that do not receive a fixed salary. Therefore, we limited our analysis to physicians working full time, but did not include working hours or salary as control variables.

Burnout

In order to assess burnout, we used the German version of the Maslach Burnout lnventory - General Survey (MBI-GS, [4, 20] which consists of three dimensions (1) exhaustion, (2) cynicism, and (3) professional efficacy. In order to compute an individual burnout score, the professional efficacy scale was inverted, and weighted average scores of all three scales were added following the approach by Kalimo et al. [21]. While in theory burnout scores could range from 0 (= never) to 6 (= every day), in the sample they were between 0.16 and 4.67.

Work-life balance

Global, subjective WLB was assessed with the German Trierer Kurzskala (TKS-WLB, [22]) consisting of five statements that can be answered on a Likert-scale from 1 (= absolutely not true) to 6 (= absolutely correct).

Statistical analyses

SPSS Version 25 was used for the statistical analysis. We compared means between internists working at a hospital and those working in a practice using independent t-tests. We used multiple linear regressions to analyze the effects of working place on burnout and WLB controlling for age, gender, marital status, and children living in the household.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Our dataset contained 183 individuals of which 51.4% were female. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study population.

Burnout and WLB: differences between physicians working at hospitals vs. practices

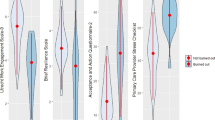

Table 2 shows raw mean differences in burnout and WLB between internists working at a hospital and those working at a practice. Internists working at a practice exhibit a lower burnout score and higher WLB.

Workplace as a predictor of burnout and WLB

Table 3 shows the regression analysis with workplace as a predictor of burnout and WLB. Physicians working in hospitals exhibit significantly lower WLB and higher exhaustion, cynicism, and total burnout score than their colleagues working in practices, but there is no effect of workplace on professional efficacy. Being male and having no children in the household both increased WLB, while professional efficacy is positively associated with age and negatively with “being in a relationship” (as opposed to being “married” or “single”).

Discussion

Our multivariate analysis showed that there were significant differences between internists working at a practice and those at a hospital in terms of WLB and all dimensions of burnout. Once we include sociographic control variables for the regression analysis, working at a practice still predicted lower exhaustion, cynicism, and total burnout as well as higher WLB.

While our study shows that inpatient-based physicians exhibit more exhaustion, the opposite is the case in the meta-analysis of Roberts et al. [15]. To some extent this could be explained by the fact that in the meta-analysis studies often refer to specific groups of physicians other than internists, like palliative care [23] or psychiatrists [24]. However, it could also be a result of the specific German situation with recent changes in the health system that were connected to physician dissatisfaction [25]. These changes affected financing, hospital capacities and privatization of hospitals, putting pressure especially on physicians working at hospitals which matches with the results from a recent study that connects working in inpatient settings with an increased wish to leave clinical work [26]. Analogous, these changes could have contributed to the higher cynicism scores in hospital-based physicians in our study which are not reflected in the international meta-analysis [15].

The described differences in exhaustion and cynicism are also reflected in the total burnout score. Following the classification of burnout scores by Kalimo et al. [21], the average score of physicians in outpatient settings (1.2) would be categorized “no burnout” (0–1.49), while the average score of their inpatient colleagues (1.9) would be classified as “some burnout symptoms” (1.50–3.45). In addition, 55.4% of physicians in hospitals would be categorized as having “some burnout symptoms”, and 4.3% would be classified as “burnout” (vs. 36.4%/ 0.0% for physicians working in practices). The fact that physicians working in inpatient settings exhibit higher burnout scores than their outpatient colleagues is supported by similar results from a study of urologists in another German state [27]. The differences could be a consequence of risk factors connected to hospital work itself like high workload [28, 29], limited autonomy [30, 31], occupational stress [32], or a mismatch between own values and those of the management [33], or a consequence of the specific characteristics of hospital physicians which are, for example, younger on average and therefore more prone to experiencing negative consequences from work-life interfering with family [34]. In addition, the results match with recent survey data showing that hospital physicians worked around 6.7 h overtime per week [35]. Future research should address interventions and strategies to mitigate burnout risk specifically at hospitals. For example, these measures could include reduced working schedules, fines for employers that systematically pressure physicians to work overtime, contracts that allow more flexibility for physicians, burnout prevention during studies, and working towards a culture that values physician health.

Doctors working at hospitals were more likely to score low on personal accomplishment/ professional efficacy in the national comparison study by Roberts et al. [16] as well as in our multivariate analysis, but the difference disappeared in the regression analysis once control variables had been added. In our sample, relationship status and even more age were associated with professional efficacy. Therefore, the higher scores of outpatient physicians may to some extent be a consequence of the fact that they were more than 15 years older on average.

WLB was higher for physicians working in an outpatient setting which matches with our results on burnout, but is different from the results of the national comparison study of US internists where recent work-home conflict was similar between groups and hospital-based physicians were more likely to agree that their work leaves enough time for their personal life [16]. The associations between reduced WLB and female gender as well as children in the household were also reflected in other research [17, 36].

Limitations

While this study has several advantages, e.g., being the first of its kind utilizing a German sample, our research also has certain limitations. First, we did not assess the number of years a physician spent at their workplace which may have an impact on burnout and WLB. Second, we excluded a relatively large number of participants (N = 67) due to missing values. Third, future research may benefit from assessing interactions between burnout and WLB with a longitudinal design, and from further differentiating our workplace variable, e.g., with regard to hospital funding or size.

Conclusions

International research shows that physicians exhibit more burnout and less WLB than the general population [1, 2]. We were interested in how far physicians` workplace is connected to these phenomena in a German setting, and our study suggests that hospital-based physicians are more affected. Hence, targeted healthcare interventions and reforms are needed to improve the situation of physicians working at hospitals in order to maintain the medical infrastructure in the long run and to improve the healthcare system for the benefit of physicians and patients alike.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012 [cited 2019 Oct 28];172(18):1377–85.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 [cited 2019 Oct 28];90(12):1600–13.

World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision); 2018. Available from: URL: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en.

Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE. MBI-general survey (MBI-GS). Palo Alto: Mindgarden; 1996.

Schwartz SP, Adair KC, Bae J, Rehder KJ, Shanafelt TD, Profit J, et al. Work-life balance behaviours cluster in work settings and relate to burnout and safety culture: a cross-sectional survey analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(2):142.

Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;7(1):41–3.

Umene-Nakano W, Kato TA, Kikuchi S, Tateno M, Fujisawa D, Hoshuyama T, et al. Nationwide survey of work environment, work-life balance and burnout among psychiatrists in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55189–9 Available from: URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23418435.

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995–1000.

Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, Satele DV, Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571–80 Available from: URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025619618303720.

Avgar AC, Givan RK, Liu M. A balancing act: work–life balance and multiple stakeholder outcomes in hospitals. Br J Ind Relat. 2011;49(4):717–41.

Klein J, Grosse Frie K, Blum K, von dem Knesebeck O. Burnout and perceived quality of care among German clinicians in surgery. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(6):525–30.

Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, Zhou A, Panagopoulou E, Chew-Graham C, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 11];178(10):1317–30.

Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, Storz KA, Reeves D, Hayes SN, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422–31 Available from: URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025619616001014.

Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Awad KM, Dyrbye LN, Fiscus LC, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019 [cited 2020 Apr 23];170(11):784–90.

Roberts DL, Cannon KJ, Wellik KE, Wu Q, Budavari AI. Burnout in inpatient-based versus outpatient-based physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):653–64.

Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176–81.

Ádám S, Györffy Z, Susánszky É. Physician burnout in Hungary: a potential role for work—family conflict. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(7):847–56.

Gandini BJ, Paulini SS, Marcos IJ, Jorge S, Luis F. The professional wearing down or syndrome of welfare labor stress (" burnout") among health professionals in the city of Cordoba. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Médicas (Córdoba, Argentina) 2006; 63(1):18–25.

Peisah C, Latif E, Wilhelm K, Williams B. Secrets to psychological success: why older doctors might have lower psychological distress and burnout than younger doctors. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(2):300–7.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Burnout inventory manual Palo Alto. Palo Alto: Consulting; 1996.

Kalimo R, Pahkin K, Mutanen P, Topipinen-Tanner S. Staying well or burning out at work: work characteristics and personal resources as long-term predictors. Work Stress. 2003;17(2):109–22.

Syrek C, Bauer-Emmel C, Antoni C, Klusemann J. Entwicklung und Validierung der Trierer Kurzskala zur Messung von Work-Life Balance (TKS-WLB). Diagnostica. 2011 [cited 2019 Feb 7];57(3):134–45.

Dunwoodie DA, Auret K. Psychological morbidity and burnout in palliative care doctors in Western Australia. Intern Med J. 2007;37(10):693–8.

Bressi C, Porcellana M, Gambini O, Madia L, Muffatti R, Peirone A, et al. Burnout among psychiatrists in Milan: a multicenter survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):985–8.

Koch K, Miksch A, Schürmann C, Joos S, Sawicki PT. The German health care system in international comparison: the primary care physicians’ perspective. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(15):255–61 Available from: URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21556263.

Pantenburg B, Luppa M, König H-H, Riedel-Heller SG. Überlegungen junger Ärztinnen und Ärzte aus der Patientenversorgung auszusteigen--Ergebnisse eines Surveys in Sachsen, Gesundheitswesen. 2014 [cited 2019 Feb 14];76(7):406–12.

Bohle A, Baumgartel M, Gotz ML, Muller EH, Jocham D. Burn-out of urologists in the county of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany: a comparison of hospital and private practice urologists. J Urol. 2001;165(4):1158–61.

Tayfur O, Arslan M. The role of lack of reciprocity, supervisory support, workload and work–family conflict on exhaustion: evidence from physicians. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(5):564–75.

Ogundipe OA, Olagunju AT, Lasebikan VO, Coker AO. Burnout among doctors in residency training in a tertiary hospital. Asian J Psychiatry. 2014;10:27–32 Available from: URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876201814000732.

Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Work hours and caseload as predictors of physician burnout: the mediating effects by perceived workload and by autonomy. Appl Psychol. 2010;59(4):539–65.

Kimo Takayesu J, Ramoska EA, Clark TR, Hansoti B, Dougherty J, Freeman W, et al. Factors associated with burnout during emergency medicine residency. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(9):1031–5.

Wu H, Liu L, Wang Y, Gao F, Zhao X, Wang L. Factors associated with burnout among Chinese hospital doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):786. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-786.

Caruso A, Vigna C, Bigazzi V, Sperduti I, Bongiorno L, Allocca A. Burnout among physicians and nurses working in oncology. Med Lav. 2012;103(2):96–105.

Fuß I, Nübling M, Hasselhorn H-M, Schwappach D, Rieger MA. Working conditions and work-family conflict in German hospital physicians: psychosocial and organisational predictors and consequences. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):353. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-353.

Marburger Bund. MB-Monitor 2019: Überlastung führt zu gesundheitlichen Beeinträchtigungen; 2019. Available from: URL: https://www.marburger-bund.de/mb-monitor-2019.

Sullivan MC, Yeo H, Roman SA, Bell RH Jr, Sosa JA. Striving for work-life balance: effect of marriage and children on the experience of 4402 US general surgery residents. Ann Surg. 2013;257(3) Available from: URL: https://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/Fulltext/2013/03000/Striving_for_Work_Life_Balance__Effect_of_Marriage.30.aspx.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This paper was supported by the State Chamber of Physicians of Saxony and the University of Leipzig. Funding did not affect the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the manuscript We acknowledge support from Leipzig University for Open Access Publishing. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FSH and IC designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. SGRH and IC contributed to the interpretation of results, and to the revision of the manuscript. EB and FJ contributed to data collection, study organization, and the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (reference number: 196/19-ek). Participants have given consent for their data to be used in the research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussenoeder, F.S., Bodendieck, E., Jung, F. et al. Comparing burnout and work-life balance among specialists in internal medicine: the role of inpatient vs. outpatient workplace. J Occup Med Toxicol 16, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-021-00294-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-021-00294-3