Abstract

Background

Medical interns are at risk of burnout due to several organizational and individual factors. There is scarcity of studies exploring the role of chronic physical illness and job dissatisfaction on burnout experience among medical interns. This study examined the prevalence of burnout syndrome and explored whether chronic physical illness and job dissatisfaction could independently predict burnout syndrome among medical interns in Oman. This cross-sectional study was conducted among a random sample of medical interns enrolled in the Omani internship program. One-hundred and eighty interns participated in this study and filled in a self-reported questionnaire that included Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS), and data related to physical illness.

Results

The prevalence of burnout syndrome was 15%. Having a physical illness (OR = 7.285, 95% CI = 1.976–26.857, P = 0.003) and job dissatisfaction (OR = 16.488, 95% CI = 5.371–50.614, P = 0.0001) was significant independent predictors of high levels of the EE subscale. In addition, having a physical illness (OR = 4.678, 95% CI = 1.498–14.608, P = 0.008) and being dissatisfied (OR = 2.900, 95% CI = 11.159–7.257, P = 0.023) were significant independent predictors of the high DP subscale. Having physical illness was independent predictors of the low personal accomplishment subscale (OR = 0.258, 95% CI = 0.088–0.759, P = 0.014).

Conclusions

Burnout syndrome is prevalent among medical interns in Oman. Job dissatisfaction and chronic physical illness are risk factors for burnout syndrome. Internship programs should consider these factors when designing burnout mitigative strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the early 1970s, the term “burnout” was introduced by an American clinical psychologist, Herbert Freudenberger, to describe a psychophysical condition brought about by mental and emotional exhaustion related to overwhelmed and overworked employees, especially in the medical field [1]. Burnout was further defined as a progressive process involving a triad: loss of idealism, energy, and purpose [2].

Christine Maslach, a social psychologist, defined the condition giving it specific psychological characteristics, namely mental exhaustion, low personal achievement, and depersonalization [3], which often lead to poor outcomes in terms of job expectations [4]. Furthermore, the condition was strongly related to jobs that provided car giving, such as healthcare workers, where the role requires decision-making and long working hours, playing a major role in developing burnout.

In 1981, Maslach and Jackson developed an inventory to evaluate individuals experiencing burnout, which was called the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). This questionnaire encompasses the three psychological characteristics associated with burnout syndrome [3]. The MBI has been used in many studies and is considered the most relevant tool to evaluate burnout.

Studies worldwide have indicated that medical students experience burnout even before getting involved in clinical rotations, notably due to concerns over their career future and routine exams, building a stressful environment [5, 6]. Burnout is both a mental and physical exhaustion. Studies have shown that the prevalence varies between 10 and 50%. Interestingly, the prevalence between males and females is equal when it comes to experiencing burnout [7]. Personality traits play a role in developing burnout, especially when it comes to the medical field, where many experience obsessive behaviors as well as being perfectionists, lowering the threshold for feeling dejected or exhausted when their goals are not achieved as expected [8].

Medical doctors are exposed to many stressors throughout their careers, making them vulnerable to experiencing burnout and depression. Some of the significant stressors leading to burnout include high workloads, immense educational demands, and lack of time to unwind and socialize [9]. Untreated cases of burnout may lead to depression, medical errors, substance abuse, and suicide among doctors [10]. Further research and early detection are necessary to avoid the negative outcomes of burnout, such as progression into other mental health disorders. Precautionary measures would should be outlined and adopted into practice in order to minimize burnout prevalence [11].

In Oman, all medical graduates are required to do a 1-year internship program after graduating from medical school. During this period, interns are expected to perform all duties under the supervision of senior medical doctors and be on-call out of hours, where they are often the first person to be contacted when a patient develops a life-threatening condition. Medical interns in Oman perform many of the same tasks as residents and general practitioners, such as taking patient histories, examining patients, meeting with family members, and performing simple medical procedures such as blood collection, catheterizations, and biopsies. They must always work under the direct supervision and guidance of a senior doctor on the team, such as a senior resident or a specialist physician. During clinical rounds, the consultant physician leading the team will often discuss the patients’ ailments in depth with the medical intern and make treatment recommendations, which are frequently carried out by the medical interns. A sudden change in the work environment can be overwhelming, with the increased workload, financial hardship, and frequent on-call duties being potential risk factors for burnout among medical interns.

A systematic review by Elbarazi et al. analyzed nineteen articles from Arab countries, focusing on burnout and job satisfaction, and they established that the prevalence of burnout among Arab medical professionals was comparable with that of non-Arab healthcare workers, with the main two subcategories of burnout being emotional exhaustion and low accomplishment [12].

The relationship between burnout and job satisfaction tends to be inversely proportionate: as job satisfaction decreases among medical professionals, the prevalence of burnout increases, as demonstrated in the literature from various Arab countries. A study from the United Arab Emirates showed that the distribution of affected individuals in terms of gender was almost the same, and the majority were married (81%) [13]. Previous studies have indicated that it is mainly emotionally exhausted individuals that show job dissatisfaction [14, 15]. However, it is still debated whether burnout leads to unsatisfied employees or if it is the other way around, though it is well understood that improvement in job satisfaction levels can reduce the consequences of burnout, such as quitting or finding other career pathways [16].

While burnout is recognized as a risk factor for chronic medical disorders such as cardiac diseases [17], the role of chronic physical illness as predisposing factor for burnout is another area that seems to have been less studied especially among medical professionals. Until now, only a few studies have explored whether employees with chronic physical health problems experience burnout in their work. Research has shown that workers with various chronic illness reported higher emotional exhaustion compared to non-chronically ill workers [17]. Furthermore, female employees working in various occupations suffering from coronary artery disease reported higher levels of burnout [18]. Taken all together, chronic health problems may therefore cause experiences of burnout. However, little is known on the effects of chronic physical illness on burnout syndrome on healthcare workers.

This study aims to find the prevalence of burnout among medical interns in Oman and to determine the impact of job dissatisfaction and chronic physical illness, on the endorsement burnout among medical interns working in public hospitals in Oman, while adjusting for potential covariates. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies of this kind targeting medical interns in Oman at least. This study may help in designing interventions that aim at preventing detrimental impact of burnout among young Omani healthcare workers.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey study designed to evaluate the prevalence and predictors of burnout and job dissatisfaction among medical interns posted in secondary and tertiary hospitals in Oman during the internship year 2019–2020.

Participant selection

All medical interns who were enrolled in the Omani medical internship program for the year 2019–2020 were included. The internship program had a total of 251 medical interns, including Omanis and non-Omanis. All interns were invited to participate. Those who did not respond to the email invitation and those with a preexisting mental illness were excluded.

Outcome measures

The Maslach Burnout Inventory

The MBI is a 22-item questionnaire, designed to measure burnout levels, which includes the evaluation of three subscales:

-

Emotional exhaustion (EE): evaluates feelings of being emotionally exhausted by one’s work. This includes nine items, with a maximum of 54 points (e.g., I feel emotionally drained by my work).

-

Depersonalization (DP): this measures impersonal responses towards patients and assesses how detached the participant feels when they are delivering patient care. This includes five items with a maximum of 30 points (e.g., I feel I look after certain patients and clients impersonally, as if they are objects).

-

Personal achievement (PA): this reflects how the participant feels regarding their competence and success at work. This includes eight items with a maximum of 48 points (e.g., I accomplish many worthwhile things in my job).

Research participants are asked to indicate their level of agreement from a 7-point Likert scale (from 0 = never to 6 = every day). High mean scores in the EE and DP subscales and low mean scores in PA subscale are indicators of a high level of burnout. According to the current literature, many researchers use the following cut points to define burnout: EE ≥ 26, DP ≥ 9, and PA ≤ 33. Construct validity and internal consistency coefficients were examined previously among Omani medical professionals and been shown to be valid and reliable [19].

The Job Satisfaction Survey

The Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) is a 36-item, self-reported survey, used to measure the level of job satisfaction. It evaluates nine domains of job satisfaction: pay, promotion, supervision, fringe benefits, contingent rewards, operating procedures, co-workers, nature of work, and communication. For each of the nine domains, there are 4 items, and participants are asked to indicate their level of agreement from a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). The score for each item may vary from 1 to 6, while the score for each dimension may vary from 4 to 24, with 4 to 12 indicating dissatisfaction, 16 to 24 indicating satisfaction, and 12 to 16 indicating ambivalence. The total satisfaction is the sum of all 36 items, total scores ranging from 36 to 216: scores of 36 to 108 indicates dissatisfaction, 144 to 216 indicates satisfaction, and between 108 and 144 indicating ambivalence. The JSS was found to be reliable and valid according to the literature [20]. In the present study, we sought to examine the internal consistency reliability among our sample.

Chronic physical illness

Chronic physical illness was measured by the presence of at least one chronic illness. The participants reported whether they had one or more of an extensive list of conditions, including respiratory disorders (for example, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea), hematological disorders (for example, sickle cell disease, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency), neurological disorders (for example, migraine), endocrine disorders (for example, diabetes, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism), gastrointestinal disorders (for example, irritable bowel disease, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease), and skin disorders (for example, eczema, psoriasis).

Sociodemographics

The questionnaire collected information about the participant’s age, gender, nationality, marital status, parenting status, financial strains, university of graduation, whether they are undertaking training in their first rotation (first 4 months of internship) or second rotation (second 4 months of internship) or third rotation (last 4 months of internship), departments and hospitals of training, exposure to workplace bullying or not being treated with respect, feeling confidence in communicating with consultants and senior consultants, whether they were considering leaving medicine and changing career, and if they thought having a well-being and resilience program during their internship year was important.

Sample size

The total number of medical interns enrolled in Oman’s internship program during the year 2019–2020 was 251. The OpenEpi® software was used to calculate the sample size. The sample size was calculated with a type-1 error of 5.0% (alpha = 0.05) and 95% level of significance, to reach a power level 80.0%, with design effect of 1. In the current literature, the prevalence of burnout among medical interns is around 20% [21, 22]. Therefore, the minimum sample size required was 125.

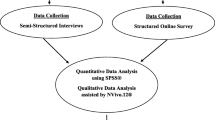

Data collection

We designed an online survey and distributed it to the medical interns through the internship program emailing system. Chief interns in each department were contacted to ask for their cooperation in explaining the study to their fellow medical interns and filling in the online questionnaire. We included all of the interns who responded and provided an electronically signed informed consent to participate in the study. Those who did not sign the consent form or provided incomplete questionnaires were excluded. To maximize the benefits of the study, along with the survey link, the participants received self-help leaflets to alleviate any preexisting, should they need help.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Sociodemographic characteristics were presented by using simple frequency. Standard deviation and mean scores were applied to continuous l variables. To measure associations between job dissatisfaction, sociodemographic factors (explanatory variables), and burnout subscales (dependent variables), the crude and adjusted odds ratios were calculated using the chi-square test. Significant variables, as defined by univariate analysis (p 0.25), were included into a stepwise logistic regression model, to determine the independent factors predicting burnout subscales after adjusting for confounders. A p-value of 0.05 was determined to be statistically significant.

Ethical approval

Electronic consent was obtained from each participant, ensuring the protection of their privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Sultan Qaboos University (MERC 2132). This study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki [23] for ethical human research. The required permits were acquired to use the MBI.

Results

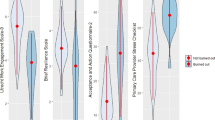

Table 1 depicts the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. The mean age was 25 years old. Females constituted 83.9% of the participants, and 84% were single. Physical illness was reported by 12% of participants. Exposure to workplace bullying was reported by 47.2% of the cohort; 97% agreed to attend a resilience and wellbeing program during their internship, with 15% of the participants reporting significant overall burnout syndrome (33.3% EE subscale, 37.2% DP subscale, and 65.6% PA subscale). Overall, job dissatisfaction was reported as the following: 22.2% dissatisfied, 71.7% was ambivalent, and 6.1% satisfied.

Table 2 represents the results of the univariate and multivariate analysis with regard to the EE subscale and explanatory variables. Marital status (OR = 4.422, 95% CI = 21.185–16.506, P = 0.027), living alone (OR = 3.903, 95% CI = 1.150–13.241, P = 0.029), place of graduation (National University of Science and Technology (NUST): OR = 4.515, 95% CI: 1.537–13.265, P = 0.006), (graduating abroad: OR = 5.494, 95% CI = 1.343–22.475, P = 0.018), having a physical illness (OR = 7.285, 95% CI = 1.976–26.857, P = 0.003), and being dissatisfied (OR = 16.488, 95% CI = 5.371–50.614, P = 0.0001) were significant independent predictors of high levels of the EE subscale.

Table 3 represents the results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of data pertaining to the high DP subscale of burnout and its explanatory variables. Place of graduation: graduating abroad (OR = 0.239, 95% CI = 0.060–0.946, P = 0.041), having a physical illness (OR = 4.678, 95% CI = 1.498–14.608, P = 0.008), and being dissatisfied (OR = 2.900, 95% CI = 11.159–7.257, P = 0.023) were significant independent predictors of the high DP subscale.

Table 4 represents the results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of the low PA data regarding burnout and its explanatory variables. Having physical illness was the only significant independent predictor of the low personal accomplishment subscale (OR = 0.258, 95% CI = 0.088–0.759, P = 0.014).

Discussion

The primary objective of this paper was to find the prevalence of burnout among medical interns in Oman and explore the role of chronic physical illnesses and job dissatisfaction on burnout endorsement by medical interns. The results indicate that the prevalence of burnout among medical interns in Oman is 15%, which is similar to the prevalence of burnout among medical interns in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia [22]. On the other hand, studies from Ireland and Mexico showed higher rates of burnout among medical interns, 21.8% [24] and 20%, respectively (20). In this study, the majority of interns (65.6%) demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, which is significantly higher than the 29.6% among interns in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia [22], 41.6% among Irish interns [24], and 34.6% among Mexican interns [21].

We could speculate two possible factors contributing to this low sense of personal accomplishment. Firstly, interns in Oman have fewer opportunities to have meaningful roles in providing patient care compared to the residents who have more significant and influential roles. Low sense of personal accomplishment incrementally improves among Omani residents to 40.8% [25]. In the current literature, several studies have demonstrated a gradual increase in the sense of PA with progress in career stages [26]. The second possible factor could be the paucity of communication skills training programs at the undergraduate level. Such training programs could improve interpersonal communications, teamwork, and effectively help in achieving patient-centered care which would, in turn, improve practitioners sense of personal accomplishment and reduce burnout [27,28,29].

In Oman, burnout has been studied across various stages of the medical career. The prevalence of burnout among Omani medical students has been reported as 7.4% [30], which is 50% less than the prevalence reported in this study. Several factors, such as longer working hours, night shifts, and on-call duties, which interns would never have experienced before, can explain such an increase [31]. A study looking at burnout among Omani doctors during their residency training reported a prevalence of 16.6% [25]. From the results of this study, we may deduce that this prevalence marginally increases from internship to residency. Conversely, the prevalence of burnout among primary care physicians (PCP) in Oman has been noted to be 6.3% [19]. This decline in burnout prevalence is probably due to the absence of certain stressors that are present during internship training, such as having to move between different hospitals, a heavy workload, and career planning issues [32].

The other objective of the current study was deciphering the relationship between job dissatisfaction, chronic physical illnesses to the burnout subscales while adjusting for covariates. According to the logistic regression analysis carried out in this study, there are several independent predictors of burnout. The results of this study indicated that medical interns who demonstrated higher levels of job dissatisfaction were five times more likely to have burnout compared to those who were satisfied or ambivalent with their job. Overworked and underpaid physicians have been reported to be more likely to be dissatisfied [33]. In Oman, interns are concerned with the paucity of employment opportunities which leads to job dissatisfaction and ultimately burnout. This observation is reflected by the existing literature, where dissatisfied physicians are more vulnerable to occupational burnout [34,35,36,37].

In the present study, regression analysis indicated that being diagnosed with a chronic medical illness was an independent factor for burnout. Interns with illnesses such as anemia, asthma, migraine, and thyroid disorders had higher levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced sense of personal accomplishment. This finding could be elucidated by the various mechanisms related to chronic physical illness including dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, metabolic disturbances, systemic inflammation, and impaired immunity functions. Such speculation is yet to be empirically validated. Another possible explanation is that physicians affected by chronic physical illnesses are more likely to experience exhaustion, fatigue, and tiredness [38], which in turn might aggravate the level of occupational stress endured during work.

In our sample, interns living alone showed higher emotional exhaustion compared to interns living with friends and family members; this could be attributed to the fact that living alone can lead to depressive symptoms, which, in turn, is positively correlated with burnout [39]. Moreover, emotional exhaustion was higher in married interns than single ones, with the existing literature indicating the same [40, 41]. This could be due to difficulties in balancing professional and spousal roles [42].

The institute that the interns graduated from was another independent predictor of burnout. International graduates and graduates from the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) demonstrated high emotional exhaustion compared to Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) graduates. This can be attributed to the familiarity of interns graduating from SQU to the working environment and the hospital staff, as those interns have received their clinical training from a medical school which has a similar set of training hospitals as the internship year. This conclusion is supported by the existing literature, which proposes that factors within the working environment are major contributors to burnout rather than personal characteristics [43]. Moreover, international graduates reflected higher DP scores compared to local graduates, possibly due to unfamiliarity with the local healthcare system and working environment [43].

Limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study does not explain the causality relationship between burnout and job dissatisfaction. Prospective cohort studies would be better to examine the causal relationship. The self-reported questionnaire used in the study has been associated with recall and social desirability bias. Based on the sample size, we can conclude that the results of the research can be generalized to the population of medical interns in Oman.

Conclusions

The present study highlights that burnout is prevalent among Omani medical interns. While several independent predictors were found to increase the risk of this phenomenon, chronic physical illness led to the highest odds of burnout syndrome among the study sample. Based on the findings of this study, it seems advisable, as part of comprehensive organizational approach, to evaluate medical interns with chronic medical illness for burnout symptoms, in order to minimize the risk of developing adverse consequences, such as progression to mental disorders. A wellbeing and resilience training program could aid in developing good mental health habits and should help future healthcare professionals to develop from internship onwards, positively impacting their career as future healthcare providers.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available with the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- MBI:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- JSS:

-

Job Satisfaction Survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EE:

-

Emotional exhaustion

- DP:

-

Depersonalization

- PA:

-

Personal achievement

- NUST:

-

National University of Science and Technology

- SQU:

-

Sultan Qaboos University

- PCP:

-

Primary care physicians

References

Kaschka W, Korczak D, Broich K (2011) Burnout: un diagnóstico de moda. Dtsch Arztebl Int 108(46):781–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22163259%0A, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22163259

MirandaAckerman RC, BarbosaCamacho FJ, SanderMöller MJ, BuenrostroJiménez AD, MaresPaís R, CortesFlores AO et al (2019) Burnout syndrome prevalence during internship in public and private hospitals a survey study in Mexico. Med Educ Online 24(1):1593785

Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Jun;15(2):103–11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27265691

Maslach C, Leiter MP, Schaufeli W (2008) Measuring Burnout [Internet]. The Oxford Handbook ofOrganizational Well Being. Oxford University Press. Available from: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211913.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199211913-e-005

Barbosa ML, Ferreira BLR, Vargas TN, Ney da Silva GM, Nardi AE, Machado S et al (2018) Burnout prevalence and associated factors among Brazilian medical students. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 14:188–95

Shamli SAl, Omrani SAl, Al-Mahrouqi T, Chan MF, Salmi O Al, Al-Saadoon M, et al (2021) Perceived stress and its correlates among medical trainees in Oman: A single-institution study. Taiwan J Psychiatry [Internet] 35(4):188. Available from: http://www.e-tjp.org/article.asp?issn=1028-3684

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Power D V, Eacker A, Harper W et al (2008) Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med 149(5):334–41

Molavynejad S, Babazadeh M, Bereihi F, Cheraghian B (2019) Relationship between personality traits and burnout in oncology nurses. J Fam Med Prim care 8(9):2898–902. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31681663

Almeida G de C, Souza HR de, Almeida PC de, Almeida B de C, Almeida GH (2016) The prevalence of burnout syndrome in medical students. Rev Psiquiatr Clin 43(1):6–10

Voltmer E, Kieschke U, Schwappach DLB, Wirsching M, Spahn C (2008) Psychosocial health risk factors and resources of medical students and physicians: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 1:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-8-46

Zis P, Anagnostopoulos F, Sykioti P (2014) Burnout in medical residents: a study based on the job demands-resources model. Garcia Campayo J, editor. Sci World J 2014:673279. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/673279

Elbarazi I, Loney T, Yousef S, Elias A (2017) Prevalence of and factors associated with burnout among health care professionals in Arab countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 17(1):491 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28716142)

Musa S (2009) Mental health problems and Job Satisfaction amongst social workers in the United Arab Emirates. Psychology

Hamaideh SH (2011) Burnout, social support, and job satisfaction among Jordanian mental health nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs 32(4):234–42. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2010.546494

Al-Omar B (2003) Sources of work-stress among hospital-staff at the Saudi MOH. J King Abdulaziz Univ Adm 17(1):3–16

Zhang Y, Feng X (2011) The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 11(1):235. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-235

Donders NCGM, Roskes K, van der Gulden JWJ (2007) Fatigue, emotional exhaustion and perceived health complaints associated with work-related characteristics in employees with and without chronic diseases. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 80(7):577–587

Hallman T, Thomsson H, Burell G, Lisspers J, Setterlind S (2003) Stress, burnout and coping: differences between women with coronary heart disease and healthy matched women. J Health Psychol 8(4):433–445

Al-Hashemi T, Al-Huseini S, Al-Alawi M, Al-Balushi N, Al-Senawi H, Al-Balushi M, et al (2019) Burnout Syndrome Among Primary Care Physicians in Oman. Oman Med J [Internet] 34(3):205. Available from: file:///pmc/articles/PMC6505344/

Spector PE (1985) Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: development of the job satisfaction survey. Am J Community Psychol 13(6):693–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00929796

Miranda-ackerman RC, Barbosa-camacho FJ, Sander-möller MJ. Burnout syndrome prevalence during internship in public and private hospitals : a survey study in Mexico. Med Educ Online [Internet]. 2019;24(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1593785

Bin Himd BG, Makhdoom YM, Habadi MI, Ibrahim A (2018) Pattern of Burnout Among Medical Interns in Jeddah. Int Ann Med 2(7)

World Medical Association (1975) Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.

Hannan E, Breslin N, Doherty E, McGreal M, Moneley D, Offiah G. Burnout and stress amongst interns in Irish hospitals: contributing factors and potential solutions. Irish J Med Sci (1971 -) [Internet]. 2018;187(2):301–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1688-7

Al Subhi A, Al Lawati H, Shafiq M, Al Kindi S, Al Subhi M, Al Jahwari A (2020) Prevalence of burnout of residents in oman medical specialty board: A cross-sectional study in Oman. J Musculoskelet Surg Res 4(3):136

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J et al (2014) Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. Population 89(3):443–51

Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A (2015) Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry 39(1):47–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0197-5

Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, Varkey A, Yale S, Williams E, et al (2015) A Cluster Randomized Trial of Interventions to Improve Work Conditions and Clinician Burnout in Primary Care: Results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med [Internet] 30(8):1105–11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25724571/

Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, et al (2009) Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA [Internet] 302(12):1284–93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19773563/

Al-Alawi M, Al-Sinawi H, Al-Qubtan A, Al-Lawati J, Al-Habsi A, Al-Shuraiqi M et al (2019) Prevalence and determinants of burnout syndrome and depression among medical students at Sultan Qaboos University: a cross-sectional analytical study from Oman. Arch Environ Occup Health 74(3):130–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2017.1400941

Id YL, Chen H, Tsai S, Chang L. A prospective study of the factors associated with life quality during medical internship. 2019;(24):1–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220608

Levey RE (2001) Sources of stress for residents and recommendations for programs to assist them. Acad Med [Internet] 76(2):142–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11158832/

Van Ham I, Verhoeven AH, Groenier KH, Groothoff JW, De Haan J (2006) Job satisfaction among general practitioners: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract 12(4):174–180

Hayran O, Sur H. Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians. 2006;(May 2014)

Elit L, Trim K, Mand-Bains IH, Sussman J, Grunfeld E (2004) Job satisfaction, stress, and burnout among Canadian gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol [Internet] 94(1):134–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15262131/

Visser MRM (2003) Smets EMA. Oort FJ medical specialists 168(3):271–275

Piko BF (2006) Burnout, role conflict, job satisfaction and psychosocial health among Hungarian health care staff: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet] 43(3):311–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15964005/

Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Behavioral sciences factors related to physician burnout and its consequences : a review. 2018;2011

Huarcaya-Victoria J, Calle-Gonzáles R. Influence of the burnout syndrome and sociodemographic characteristics in the levels of depression of medical residents of a general hospital. Educ Medica [Internet]. 2020;(xx):1–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2020.01.006

Yang G, Liu J, Liu L, Wu X, Ding S, Xie J (2018) Burnout and resilience among transplant nurses in 22 hospitals in China. Transplant Proc 50(10):2905–2910

Choi BS, Sun Kim J, Lee DW, Paik JW, Chul Lee B, Won Lee J et al (2018) Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in South Korean nurses: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Investig 15(7):670–676

Demir A, Ulusoy M, Ulusoy MF (2003) Investigation of factors influencing burnout levels in the professional and private lives of nurses. Int J Nurs Stud 40(8):807–27 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14568363/)

Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T (2016) A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ 50(1):132–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12927

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank all the participants in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TM and HS designed the study; NB, TM, and AG involved in data collection; and SJ provided data analysis and statistical expertise; the initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by MA, AG, and TM and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision; MA, HS, NB, and TM contributed to conceptual work, framework, draft write-up, editing, and critical evaluation. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Electronic consent was obtained from each participant, ensuring the protection of their privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Sultan Qaboos University (MERC2132) January 2020.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Mahrouqi, T., Al-Sinawi, H., Al-Ghailani, A. et al. The role of chronic physical illness and job dissatisfaction on burnout’s risk among medical interns in Oman: a study of prevalence and determinants. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 29, 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00221-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00221-0