Abstract

Background

Flavonoids are a class of plant and fungus secondary metabolites and are the most common group of polyphenolic compounds in the human diet. In recent studies, flavonoids have been shown to induce browning of white adipocytes, increase energy consumption, inhibit high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity and improve metabolic status. Promoting the activity of brown adipose tissue (BAT) and inducing white adipose tissue (WAT) browning are promising means to increase energy expenditure and improve glucose and lipid metabolism. This review summarizes recent advances in the knowledge of flavonoid compounds and their metabolites.

Methods

We searched the following databases for all research related to flavonoids and WAT browning published through March 2019: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Web of Science. All included studies are summarized and listed in Table 1.

Result

We summarized the effects of flavonoids on fat metabolism and the specific underlying mechanisms in sub-categories. Flavonoids activated the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), promoted the release of adrenaline and thyroid hormones to increase thermogenesis and induced WAT browning through the AMPK-PGC-1α/Sirt1 and PPAR signalling pathways. Flavonoids may also promote brown preadipocyte differentiation, inhibit apoptosis and produce inflammatory factors in BAT.

Conclusion

Flavonoids induced WAT browning and activated BAT to increase energy consumption and non-shivering thermogenesis, thus inhibiting weight gain and preventing metabolic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

White fat cells are unilocular, and their main function is to store energy in the form of triglycerides. In contrast, brown adipocytes are multilocular, contain substantial numbers of mitochondria and have high expression uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). Brown adipose tissue has been found in newborns and is involved in non-shivering thermogenesis. The primary function of brown fat is to transform energy into heat and maintain body temperature. BAT has long been thought to be absent in adult humans until Nedergaard [1] reported the discovery of some BAT in the supraclavicular and the neck regions of adult humans. In contrast to the components of classic BAT, Cannon and Nedergaard [2] found another kind of adipocyte in white adipose tissue after chronic treatment with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ agonist rosiglitazone; these other adipocytes are namely “Brite adipocytes” or “beige adipocytes” that also express UCP1 and proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α). These cells are also multilocular, with moderate mitochondrial content [3] and inducible expression of UCP1 and exhibit an interphase arrangement with white fat cells in WAT, thus are also called induced BAT (iBAT) [2]. Similar to BAT, iBAT also has thermogenic capacities [4] and the ability to prevent weight gain and metabolic disorders and promote whole-body energy balance [5, 6].

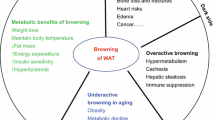

Although adults also hav brown fat, BAT metabolic effects and/or mass decline as healthy humans age [7, 8]. Ageing is associated with an increasing incidence of metabolic syndromes such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NFALD) and other disorders. The age-dependent disappearance of these brown adipocytes is associated with the development of insulin resistance and the accumulation of body fat [8]. Many studies have demonstrated that reversing age-related decreases in BAT or inducing WAT browning could be a potential strategy to treat age-related metabolic disorders [9,10,11]. However, in some hypermetabolic conditions (cancer, burns and massive trauma), studies have also found WAT browning and adipose tissue wasting. Researchers think that WAT browning enhances whole body energy expenditure causing a catabolic state of muscle protein breakdown and increased lipolysis, ultimately leading to cachexia [12].

Flavonoids, members of the polyphenol family, are a large group of natural compounds with more than 4000 types and are mainly extract from fruits, vegetables, and teas [13]. According to their structure, flavonoids has been divided into 12 subgroups: anthoxanthins (flavone and flavonol), anthocyanidins, flavanones, flavanonols, flavans, and isoflavonoids. The basic structures of flavonoids are shown in Fig. 1. Six of flavonoids are found in significant quantities in our diet [13]. These active small compounds have been demonstrated to possess anti-inflammatory [14], antioxidative [15], anticancer [16, 17], anti-obesity activity, etc. [18]. In recent studies, several kinds of flavonoids have been found to induce WAT browning and promote energy balance in humans and animals [19–21]. Kang found that flavonoid derivatives increase energy expenditure through non-shivering thermogenesis [22]. Azhar identified some phytochemicals (guggulsterone, resveratrol, capsinoids etc) as inducers of browning in white adipose tissue [23]. Compared with flavonoids, non-flavonoids have a similar mechanism of promoting the browning of WAT. For example, resveratrol has been shown to induce the browning of WAT through the AMPK/PGC-1α/Sirt1 and PPARγ pathways. However, non-flavonoids also have a unique mechanism of promoting browning of WAT. For example, capsaicin and cinnamaldehyde combine with the intestinal transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptor to activate the SNS, which in turn promotes WAT browning and thermogenesis. Considering the functional differences caused by the different structures of the different compounds, we chose to summarize the effects and mechanisms of flavonoids. However, none of the long-term follow-up clinical or in vivo studies have demonstrated that flavonoids can promote human health, leaving it impossible to say if these activities have any beneficial or detrimental effect on human health. In this review, we will summarize recent works on flavonoids and brown adipose tissue and discuss the mechanism underlying the promotion of WAT browning by flavonoids.

Methods

We used the MeSH terms “flavonoid”, or “flavone” and “browning” or “brown adipose tissue” or “BAT” or “beiging” to search the following databases for all research related to flavonoids and WAT browning published through March 2019: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Web of Science. Furthermore, we examined the reference lists of eligible articles and review studies by hand to identify additional studies. There were no restrictions with regard to species, age, sex, or publication type. The search was limited to articles published in English.

Results

Studies were included when the following inclusion criteria were met: (1) the target compound of the study was flavonoids or their metabolites; (2) specific markers for brown fat were detected in the study; (3) the study researched related mechanisms; (4) the study indicated the concentration of related compounds and the processing time, and related results were reported; and (5) animal experiments were supported by the relevant ethics committees. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) non-flavonoid-related research; (2) no mechanism was studied; (3) failure to pass ethical review; (4) no detection of brown-fat-related markers; (5) lack of reported dose, duration, or results. Unpublished studies and conference abstracts were also excluded because they cannot provide enough information. We classified all included studies by subgroup. All studies met the inclusion criteria are included in Table 1. We summarized the source of the compound, the animal species, age, cell lines or cell type, in vivo/in vitro study, dose/duration, effects and underlying mechanisms.

Discussion

Flavonoids and WAT browning

Flavonol

Flavonols are a group of 3-hydroxy-4-keto-flavonoids that mainly include kaempferols, quercetin, and rutin. Quercetin is extracted from onion peel and has been demonstrated to have many biological functions, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-obesity effects [70]. Many studies have demonstrated that quercetin supplementation prevents HFD-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome and increases the expression of UCP1 and thus thermogenesis through the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signalling pathway [24,25,26,27, 71, 72]. In diet-induced obese C57Bl/6 J mice, quercetin significantly increased the expression of UCP1 and Elovl3, specifically in subcutaneous white adipose tissue (sWAT). Quercetin also decreased plasma triglyceride (TG) levels and increased TG-derived FA uptake by sWAT as a consequence of WAT browning in HFD mice [28]. These results indicated that quercetin may induce WAT browning to achieve its anti-obesity effect through the AMPK-Sirt1 pathway [29, 73]. In 3 T3-L1 preadipocytes, quercetin and its metabolite isorhamnetin inhibited adipogenic differentiation by decreasing the expression of PPARγ, C/EBPα, FABP4, aP2, and lipoprotein lipase (LPL), but quercetin also increased the expression of brown-like adipocyte-specific genes, such as positive regulatory domain containing 16 (PRDM16), UCP1, fibroblast growth factor (FGF21), T-box transcription factor 1 (TBX1), PGC-1α and cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor alpha (DFFA)-like effector α (CIDEA) [30, 31, 74]. In conclusion, quercetin might prevent adipogenic differentiation but also induce the beiging of white adipocytes through the AMPK and PPARγ pathways to prevent obesity.

Rutin, also called vitamin P, is a kind of flavone glycoside. Rutin is found mainly in buckwheat and usually coexists with quercetin [75]. Rutin has been shown to protect mice from HFD-induced obesity and adipocyte hypertrophy, and to up-regulate the transcription of genes (deiodinase 2 (Dio2), Elovl3, PGC-1α, UCPs) involved in energy expenditure in BAT and to maintain glucose sensitivity [32]. In db/db and diet-induced obese (DIO) mice, rutin treatment significantly reduced adiposity, increased energy expenditure, and improved glucose homeostasis. The expression levels of UCP1, PGC-1α, PGC-1β, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 alpha (CPT-1α), and PPARα increased significantly in sWAT after rutin treatment. The underlying mechanism is as follows: rutin binds to and stabilize Sirt1 to increase Sirt1-mediated PGC-1α deacetylation, which stimulates Tfam transactivation and eventually augments the number of mitochondria and UCP1 activity in BAT [19]. Therefore, rutin has been thought to be of potential health benefits against diabetes and related disease [76].

Dihydromyricetin has been shown to stimulate irisin secretion partially through the PGC-1α pathway. Another study demonstrated that irisin could stimulate UCP1 expression in WAT and cause an increase in energy expenditure in mice [6, 77]. Our unpublished results indicated that dihydromyricetin also induced WAT browning. The underlying mechanism is that dihydromyricetin activates the PGC-1α/irisin axis.

Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins are a class of compounds including cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and petunidin. Anthocyanins are mainly found in dark- coloured fruits and vegetables. Jin found that cyanidin-3-glucoside (Cy-3-G) treatment increased energy expenditure, reversed metabolic syndrome and enhanced BAT activity in obese db/db mice. Cy-3-G also induces brown-like (beige) adipocyte formation and increases UCP-1 expression and mitochondrial number and function in the sWAT of db/db mice [33]. In vivo, Cy-3-G significantly reduced the signs of metabolic syndrome and body weight induced by HFD [78, 79]. Another study found that Cy-3-G also reduced inflammatory cell infiltration in the heart and liver [80]. Yang found that in HFD-fed mice, Cy-3-G improved the function of BAT and regulated the expression of adipokines (NRG4 and PGC-1α) in BAT. In preadipocytes and C3H10T1/2 clone8 cells, Cy-3-G inhibited the release of FGF21 [34]. In vitro, a previous study showed that Cy-3-G promoted preadipocyte differentiation by elevating intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), promoting C/EBPβ expression, and increasing the expression of mitochondrial genes (TFAM, SOD2, UCPs), UCP1 protein and beige adipocyte markers (CITED1 and TBX1) in 3 T3-L1 cells [35]. Mulberry extract, which contains mainly Cy-3-G, was found to elevate the expression levels of UCP1, PGC-1α, and PRDM16 during brown adipogenesis through the p38 MAPK pathway in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal stem cells [36]. Although we have enough animal data [34, 78,79,80] to prove the role of anthocyanins, we still lack a large amount of clinical data to prove that anthocyanins can reduce the risk of diseases in humans.

Flavan-3-ols

Flavan-3-ols are a group of flavonoid substances including catechin, epicatechin gallate, epigallocatechin, proanthocyanidins, theaflavins, and thearubigins that are found in some plant foods such as cocoa beans, wine, and certain fruits. Flavan-3-ols consist of monomers and oligomers composed of catechins and their derivatives. In an in vivo study, the mRNA levels of UCP1 and PGC-1α in BAT increased significantly 2 h after the administration of flavan-3-ols, and the serum adrenaline concentration was significantly increased 2 h after treatment with flavan-3-ols [37]. In another study, after 2 weeks of administration of flavan-3-ols, the levels of UCP1 and mitochondria also increased significantly in BAT, which indicated that flavan-3-ols enhanced lipolysis and promoted mitochondrial biogenesis [38]. When HFD-fed rats were treated with flavan-3-ols, the expression levels of UCP1 protein increased in the BAT group compared with the levels in the HFD group [39].

The monomers of flavan-3-ols include catechin, (+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin, (−)-epigallocatechin, (+)-gallocatechin, and their gallate derivatives. Catechins and their derivatives are abundant in tea and can promote energy balance. In an in vivo study, catechin was shown to reduce perirenal WAT weight and increase UCP1 mRNA expression in BAT after the consumption of a normal-fat diet for 8 weeks. The researchers concluded that catechins suppressed body fat accumulation by increasing UCP1 expression in BAT [40]. In another study, a single oral treatment with theaflavins significantly increased REE and the UCP1 and PGC-1α levels in BAT after 2 h. The researchers believed that theaflavins enhanced systemic energy expenditure by promoting AMPK1α phosphorylation and UCP1 and PGC-1αexpression in BAT [41]. Catechins and their derivatives are the main flavonoid components in tea. Several studies have reported that the intake of tea enhanced the phosphorylation of AMPK and modulated the PPAR pathway to increase the expression of UCP1 in WAT and thermogenesis through sympathetic stimulation [42,43,44]. (−)-Epicatechin (Epi), a cacao flavanol, increased fatty acid metabolism and upregulated the expression of brown adipose tissue-specific proteins in a high-fat diet-induced mouse model of obesity and cultured human adipocytes [45].

Flavones

Flavones are another subclass of flavonoids and include chrysin, luteolin, apigenin, and baicalein. Chrysin is a natural flavone found in flowers, honeycombs, and mushrooms. Choi found that chrysin significantly enhanced the expression levels of brown fat-specific genes (CIDEA, PGC-1α, PRDM16, TBX1, TMEM26, and UCP1) and the protein levels of brown fat markers, including CEBP/β, PGC-1α, PRDM16 and UCP1 in 3 T3-L1 adipocytes, suggesting possible conversion of white adipocytes into beige cells. In another study, they found that chrysin promoted the BAT phenotype through an AMPK-mediated pathway. The AMPK pathway inhibitor dorsomorphin reduced the expression of UCP1, PRDM16, and PGC-1α while the activator AICAR elevated the expression of these brown fat-specific genes [46]. Luteolin is a natural flavonoid and is most often found in leaves of pepper, celery, thyme, peppermint, and honeysuckle. Zhang reported that dietary luteolin supplementation increased energy expenditure in both HFD-fed and LFD-fed mice through the upregulation of thermogenic genes in brown and subcutaneous adipose tissues. Luteolin promotes the differentiation of subcutaneous adipose cells into brown fat cells, and it works by promoting adipocyte differentiation through the activation of the AMPK/PGC-1α pathway [20]. Nobiletin (NOB) is a polymethoxylated flavone isolated from citrus peels. Yun found that NOB not only activated HIB1B brown adipocytes but also induced mitochondrial biogenesis and browning of 3 T3-L1 white adipocytes. NOB also ameliorates stress and inhibits autophagy in adipocytes to sustain the brown adipocyte-like phenotype. The researchers found that NOB induced PKA and activated AMPK and consequently increased the expression of PGC-1α and UCP1. Inhibiting PKA and p-AMPK by H-89 and dorsomorphin abolished the expression of PGC-1α and UCP1 [47]. Sudachitin is a polymethoxylated flavone that is found in Citrus sudachi hort. ex. Shirai. In HFD-fed mice, sudachitin treatment resulted in lower body weight, improved glucose tolerance, and better insulin sensitivity. Moreover, the mRNA transcripts of UCP1 and UCP3 were significantly increased in WAT and adipocyte size and number also decreased after 12 weeks of sudachitin treatment [48].

Flavanones

Flavanones include hesperetin, naringenin, eriodictyol, etc. Flavanones are found in the peels of fruits such as satsuma mandarin orange and Valencia orange and are often found in plants as glycosides. One of the flavanones, hesperetin, has been found to increase thermogenesis. Researchers have found that oral administration of 60 mg of G-hesperidin increased interscapular BAT-SNA but decreased cutaneous sympathetic nerve activity (CASNA) in rats, and significantly increased subcutaneous body temperature (BT) [49].

Naringenin, a flavonoid found in a variety of fruits and herbs, has also been considered to be a bioactive compound that can protect against adiposity. A large amount of evidence has indicated that naringenin prevents metabolic syndrome by inhibiting diet-induced dyslipidaemia [50], lipogenesis [81] and adipogenesis [51]. Furthermore, naringenin supplementation activates PPARα and upregulates fatty acid oxidation target genes [52]. Naringenin increases hepatic fatty acid oxidation through the PGC-1α/ PPARα-mediated pathway [50]. In an unpublished study, the author showed that naringenin increased the expression of UCP1 and Sirt1 in primary human omental adipocytes in a dose-dependent manner [23]. In a soy protein diet-fed SD rat model, the author found that the protein, not the isoflavones, reduced hepatic lipogenesis, but they also found that the isoflavones regulated hepatic fatty acid oxidation and upregulated the expression of UCPs in BAT through a PPARγ-dependent mechanism [53].

Isoflavones

Isoflavones are mainly found in the Fabaceae family. Isoflavones include daidzein, genistein, glycitein, biochanin A, formononetin, and their metabolites. Lephart found that diets rich in isoflavones increased T3 levels and UCP1 mRNA levels in the BAT of Long-Evans rats, but the core body temperature decreased except near the end of the dark phase of the dark/light cycle [54]. Genistein is found in particularly high levels in soybean. Aziz found that genistein treatment changed the lipid distribution of 3 T3-L1 adipocytes, reduced white adipocyte-specific genes and increased brown/beige adipocytes specific genes. They also found that genistein stimulated WAT browning by activating Sirt1 to promote the expression of UCP1, C/EBPβ, and PGC-1α. They concluded that genistein acts directly on adipocytes or on adipocyte progenitor cells to programming the cells metabolically to adopt features of beige adipocytes [55]. Another kind of isoflavone, daidzein, was also found to prevent diet-induced obesity. Chronic treatment with daidzein for 14 days, reduced weight gain and fat content in the liver. This general physiological effect shows a complex interaction of many different factors through various possibly interrelated pathways and with a particular role of the inhibition of lipogenesis, involving PPARγ and the enzyme SCD1 [56].

Flavonolignan

Silibinin belongs to the flavonolignangroup and is the major active constituent found in milk thistle (Silybum marianum). Volti found that Silibinin treatment affects the adipogenic differentiation and lipids of mature adipocytes of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs). In their study, silibinin was added either at the early or late stage of adipogenic differentiation, Silibinin both increased BAT-specific gene expression (Sirt-1, PPARα, PGC-1α, and UCPs) and also decreased WAT specific gene expression (PPARγ, fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4)). Moreover, when mature adipocytes formed, silibinin treatment decreased the lipid droplets in mature adipocytes. This result indicates that silibinin induces thermogenesis and WAT browning by stimulating Sirt1, PPARα, and PGC-1α [21].

Proanthocyanidins

Proanthocyanidins are oligomeric flavonoids, mainly found in fresh grapes, red wine, and other dark pigmented fruits. In a rat model of HFD-induced obesity, propanthocyanidin supplementation inhibited the weight gain induced by a high-fat diet, increased the activity of cytochrome c oxidase activity, and enhanced UCP1 expression in brown adipocytes. The data indicate that chronic administration of proanthocyanidins enhances thermogenic capacity and improves mitochondrial function in the BAT of cafeteria-diet-induced obese rats [57]. Zhou found that proanthocyanidin extracts (PEs) from Chinese bayberry play an anti-obesity role by upregulating the expression of Sirt1, thus inducing the deacetylation of PPARγ, downregulating the expression of C/EBP-α and upregulating the expression of BMP4 to induced white-to-brown adipocyte transdifferentiation [58]. In another study, acute administration of Proanthocyanidin extract significantly improved lipid metabolism, and increased energy metabolism-related genes such as PGC-1α, and upregulated the oxidative capacity of skeletal muscle and BAT mitochondria [59]. Flavangenol is mainly found in French maritime pine bark. HFD-induced obesity was suppressed by flavangenol ingestion, and acute intraduodenal (ID) injection of flavangenol elevated BAT-SNA and inhibited gastric vagal nerve activity (GVNA) in anaesthetized rats. In addition, flavangenol elevated BAT-temperature in conscious rats. These results indicate that flavangenol inhibits obesity by influencing autonomic nerves and the thermogenic response [60].

Xanthohumol

Xanthohumol is a prenylated flavonoid found in the female inflorescences of Humulus lupulus. In an in vitro study, xanthohumol was demonstrated to inhibit preadipocyte differentiation and intracellular fat droplet accumulation [62] and induce apoptosis through oxidative stress in mature adipocytes [63]. In vivo, xanthohumol also inhibits HFD-induced weight gain and promotes lipid metabolism [82]. Xanthohumol also increases the energy expenditure of white and brown preadipocytes, hepatocytes and myocytes [83]. This effect was mediated by increasing the production of ROS, which leads to the activation of AMPK and PGC-1α and increasing uncoupling and oxygen consumption [83]. The administration of mature hop plants to rats induced thermogenesis and UCP1 expression in BAT. The authors found that the administration of mature hop plant components increased the cAMP concentration in BAT and activated the β-adrenergic signalling cascade, thereby modulating sympathetic nerve activity. They concluded that BAT-SNA activation plays an important role in mature hop component-induced thermogenesis [64]. Because xanthohumol can increase the oxygen consumption rate and the potential for chemical uncoupling, it is thought that xanthohumol may induce this metabolic change through systemic thyroid hormone signalling. In a xanthohumol-feeding rat experiment, xanthohumol affected tetraiodothyronine (T4) binding and distribution both in vivo and in vitro. Xanthohumol also moderately increased serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and triiodothyronine (T3) levels [84]. Additionally, other groups found acute administration of xanthohumol to increased iodide uptake after 3 days in nontransformed rat thyrocytes [85]. Xanthohumol might impact BAT activity through thyroid hormone signalling.

Plant extract mixture

Black soybean seed coat extract (BE) is a polyphenol-rich food material that mainlyconsists of Cy-3-G, catechins, and procyanidins. In HFD-fed C57BL/6 mice, BE exerted a protective effect against body weight gain and rescued glucose metabolism; BE also increased UCP1 expression in BAT. Researchers concluded that dietary BE consumption enhanced energy expenditure by upregulating UCPs expression [65]. Fortunella margarita fruit extract (FME) mainly contains polyphenols and flavonoids including neoeriocitrin and poncirin. The administration of FME along with an HFD blocked the HFD-induced body weight gain and decreased serum lipid levels. Consumption of the FME diet also increased the expression of UCP-2 but not UCP1 in BAT, and the expression of PPARα and its target genes in the liver increased significantly [66]. Cacao liquor procyanidin (CLPr) extract, mainly consists of catechin, epicatechin, and procyanidins. CLPr suppressed HFD-induced metabolic disorder in WAT. CLPr also promoted the translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) and the phosphorylation of AMPKα in the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle and BAT. Phosphorylation of AMPKα was also enhanced in the liver and WAT. CLPr upregulated the gene and protein expression levels of UCP1 in BAT and UCP-3 in skeletal muscle [61]. Puerariae flower extract mainly consists of isoflavones. These compounds may increase energy expenditure by upregulating BAT UCP1 expression in HFD-fed C57BL/6 J male mice [67]. Olive leaf extract (OLE) contains a wide variety of phenolic acids, phenolic alcohols, flavonoids, and secoiridoids. The major component of these compounds is oleuropein and its major metabolite hydroxytyrosol. Researchers showed that OLE treatment induces thermogenesis by activating of UCP1, Sirt1, PPARα, and PGC-1α. OLE significantly decreases the expression of genes involved in adipogenesis and upregulates the expression of mediators involved in thermogenesis and lipid metabolism. OLE treatment resulted in a significant increase in pAMPK and HO-1 expression during adipose differentiation [68]. Green tea extracts (GTEs), particularly the catechins and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), reduce the expression of Ap2 in BAT, increase the expression of PGC-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor α (VEGFα), counteract the whitening of the BAT and induce the browning process in the WAT of HFD-induced obese mice [86]. Brown alga ecklonia cava polyphenol extract has been demonstrated to reduce HFD-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome and might have potential anti-obesity effects via the regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism, inflammation, and oxidative stress through the activation of AMPK/Sirt1 and the regulation of its downstream genes in HFD-induced obese mice [69].

The pathways involved in flavonoid-induced WAT Browning

Sympathetic nervous system

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) plays a decisive role in the thermogenesis of brown adipose tissue. When the body is exposed to cold, the temperature-sensitive neurons located on the skin surface feel cold stimulation, activate the sympathetic nervous system and release adrenaline, which binds to its receptors, promotes the activation of brown adipocytes and the browning of white adipose tissue and increases the expression of UCP-1 to generate heat [87]. Cold exposure increases Sirt1 phosphorylation/activity in both skeletal muscle and BAT, increasing thermogenesis and insulin sensitivity through the deacetylation of PGC-1α and other protein targets. Sirt1 increases insulin sensitivity and glucose control in skeletal muscles, triggers the browning of white fat and increases BAT activity. Adrenergic stimulation of BAT increases intracellular cAMP release and activates protein kinase A (PKA), leading to p38 MAP kinase activition and phosphorylation of nuclear-thermogenic-related genes such as ATF2 and PGC-1α to increase the transcription of the UCP1 gene [88]. The activation of PKA also boosts lipolysis in BAT cells [89]. AR-β activation of p38 MAP kinase in brown adipocytes activates the transcription of UCP1 and PGC-1α genes for adaptive thermogenesis, mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. β3 adrenoceptor (β3-AR) stimulation leads to PGC-1α induction, which drives PPAR activation and mitochondrial biogenesis. The amount of heat produced by BAT mainly depends on the degree of activation of BAT sympathetic nerves, the extent of the subsequent norepinephrine release, and the intensity of the binding of released norepinephrine to the adrenergic receptors. In a case report study, a man with pheochromocytoma exhibited elevated plasma catecholamine and urinary catecholamine metabolite levels; PET/CT revealed increasing BAT activity in the neck, supraclavicular, axillary, mediastinal, paravertebral, and perinephric regions, which disappeared after resection of the tumour [90]. In contrast, blocking adrenergic receptors with propranolol completely diminished FDG uptake in BAT areas, suggesting the involvement of these adrenergic receptors in BAT activation in humans [91]. The catechins in green tea are believed to influence energy expenditure through the inhibition of the enzyme catechol-0-methyl transferase [92,93,94]. This enzyme is responsible for the degradation of catecholamines including norepinephrine. Because the degradation of norepinephrine and epinephrine are slowed, continuous stimulation of adrenergic receptors occurs with a resultant increase in energy expenditure and fat oxidation.

Thyroid hormone

Thyroid hormones (THs) are important physiological modulators of lipid metabolism. Brown adipose tissue is the main target tissue of THs. In brown adipocytes, THs can enhance thermogenesis by promoting the expression of UCP-1 in mitochondria. This is achieved by thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) interacting with PGC-1α and binging to the UCP1 enhancer region, resulting in increased UCP1 expression in mitochondria [95]. Total TRβ knockout mice present with defective adaptive thermogenesis and reduced BAT UCP1 expression, whereas the selective TRβ agonist GC1 along with noradrenaline increases UCP1 expression in brown adipocytes [96, 97]. Several lines of evidence indicate that THs regulates WAT browning. Medina-Gomez found that low doses of the T3 metabolite triiodothyracetic acid (TRIAC) induces ectopic expression of UCP1 in abdominal WAT [98]. López et al. found that intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of THs decreased the activity of hypothalamic AMPK but increased BAT sympathetic nerve activity and UCP1 expression, which was associated with weight loss without affecting food intake [99]. The researchers also found that inhibition of thyroid hormone receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) reverses the weight loss associated with hyperthyroidism. They concluded that THs activates TRs in the VMH to regulate BAT function through the SNS. Importantly, the effects of T3 on energy expenditure, thermogenesis and body weight were abolished in UCP1 knockout mice [100]. In human adipose tissue-derived multipotent cells, T3 treatment induced PGC1α and UCP-1 expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in a TRβ-dependent manner [101]. In a thyroid cancer patient case study, [18F]FDG-PET/CT scanning revealed that T4 supplementation for 14 days increased radioactive glucose uptake and UCP-1 expression in suprascapular BAT and subcutaneous WAT regions [102]. Recent human data demonstrated that UCP1 expression in WAT is associated with serum T4 levels, suggesting that THs is positively associated with fat browning [103]. Lephart found that after feeding Long-Evans rats with a diet low in isoflavones, body and adipose tissue weights decreased but circulating T3 levels increased while body temperatures decreased with soy consumption. They thought the results were related to isoflavones mimicking the oestrogen effect to increase T3 and T4 [54]. In an in vitro study, kaempferol (KPF) increased energy expenditure and modified metabolic gene expression (UCP-3, PGC-1α) by activating the cAMP-PKA pathway. This result may be due to kaempferol increasing Dio2 activity by regulating T3 expression. The effect of KPF can be mimicked by dibutyryl cAMP, a stable cAMP analogue [104]. The synthetic flavonoid EMD 21388 has been demonstrated to inhibit T4 production and increase T3 production [105]. In conclusion, flavonoid consumption might increase T3 to induce WAT browning and upregulate UCP-1 expression in BAT. Central T3 regulates hepatic metabolism through the vagus nerve and BAT through the SNS, leading to increased lipid oxidation and thermogenesis. This physiological pathway is mediated by AMPK (specifically in SF1 neurons of the VMH), which also exerts a dichotomic action on ceramide-induced ER stress and C-Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK1).

AMPK-PGC-1α/Sirt1 signalling pathway

AMPK is an enzyme (EC 2.7.11.31) that is highly expressed in the brain, liver, skeletal muscle and BAT, and plays a role in energy metabolism and regulating thermogenesis [106]. AMPK activates glucose and fatty acid uptake and oxidation when cellular energy is low. The enzyme complex comprises three subunits: a catalytic α subunit and two regulatory subunits, β and γ. The catalytic α subunit is mainly found in rodents, and the α1 isoform is predominant in the brain and WAT whereas α2 is mainly expressed in muscle. In C57Bl/6 mice, AMPKα1 is the dominant isoform that is mainly expressed in BAT [107]. Chronic cold exposure selectively stimulated the AMPKα1 isoform and maintained the high mitochondrial density in BAT. Recent data demonstrated that the activation of AMPK leads to PGC1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis and UCP-1 expression in BAT. PGC-1α is an important regulatory factor in the process of mitochondrial formation, oxidative metabolism and thermogenesis in BAT. PGC-1α is a master regulator of BAT thermogenesis [108]. PGC-1α coactivates various nuclear receptors for the transcriptional induction of UCP1 and other mitochondrial genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism [109]. AMPK and Sirt1, two key regulators of energy metabolism, can increase PGC-1α expression and phosphorylation [110, 111]. Moreover, AMPK can also enhance Sirt1 activity by increasing cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) levels to induce PGC-1α deacetylation and activation [73, 112]. AMPK/PGC-1α signalling dominantly regulates differentiation and function in brown and beige fat [106, 112, 113]. Recent studies have shown that flavonoids can promote WAT browning and thermogenesis and inhibit adipocyte differentiation through the AMPK/PGC-1α pathway. For instance, luteolin enhanced energy expenditure and upregulated thermogenic genes in brown and subcutaneous adipose tissues (SAT). Luteolin has also been demonstrated to suppress adipogenic differentiation by activating AMPK/Sirt1 signalling. Luteolin treatment elevated the expression of UCP-1 and the activity of AMPK/PGC-1α signalling molecules in differentiated primary brown and subcutaneous adipocytes, which were fully mimicked by the AMPK activator 5-amino-4-formamide imidazolium ribonucleotide (AICAR). Furthermore, the AMPK inhibitor compound C could reverse the effects of luteolin and AICAR [20]. These results indicate that luteolin induces adipocyte browning and thermogenesis by activating AMPK/PGC-1α signalling. Other flavonoids, such as rutin [19], Cy-3-G [36], and chrysin [46], have also been demonstrated to induce adipocyte browning and thermogenesis by activating AMPK/PGC-1α signalling.

PPARs

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are a group of nuclear transcription factors that function by regulating cellular differentiation, development, and energy metabolism and tumourigenesis. There are three types of PPARs: PPARα, β or δ, and γ. PPARα is mainly expressed in the liver, kidney, heart, muscle and adipose tissue and mediates the hypotriglyceridaemic effect of fibrates by inducing mitochondrial and peroxisomal-oxidation by decreasing the plasma concentration of triacylglycerol-rich lipoproteins [114]. PPARδ is mainly expressed in the brain, BAT, and skin. PPARδ is one of the central regulators of adipogenesis that promotes lipid storage in adipocytes [113]. PPARδ regulates the expression of genes required for fatty acid oxidation and energy dissipation, which led to improved lipid profiles and reduced adiposity [115]. PPARγ is mainly expressed in WAT, internal organs and macrophages. In mature adipocytes, PPARγ regulates the expression of genes involved in free fatty acid uptake and triglyceride synthesis, thereby increasing the ability of WAT to store triglycerides [116]. The PPARγ agonist thiazolidinedione can also induce a brown-like phenotype in white adipocytes by promoting the expression of brown adipocyte-specific genes and inhibiting visceral WAT genes [117]. The mechanism of this “browning” effect is related to the Sirt1-dependent PPARγ deacetylation of Lys268 and Lys293, which is required to recruit the BAT programme coactivator PRDM16 to PPARγ, leading to the selective induction of BAT genes and the repression of visceral WAT genes associated with insulin resistance. [118]. Increasing the levels of PPARδ in WAT is suggested as a potential strategy to treat obesity [119]. In a diet-induced obesity model, the PPARα agonist fenofibrate, elicits weight loss and increases β3-AR, PGC-1α and UCP-1 in brown adipocytes [120]. YAN et al. found that green tea catechins increased PPARδ but not PPARα levels in both BAT and WAT. In addition, the expression levels of PPARδ down-stream genes such as alternative oxidase (AOX), CPT1, and UCP1 were increased [43]. Once again, PPARα controls the transcription of this essential gene, which interacts with PGC-1α to provide the machinery necessary for the transdifferentiation or differentiation of the brite adipocyte [121].

Conclusion

In this study, we summarized the role of flavonoids in metabolic diseases, and analysed the specific mechanism of flavonoid-induced WAT browning (Fig. 2). Flavonoids activated the SNS and promoted the release of adrenaline and thyroid hormones to increase thermogenesis and induce WAT browning through the AMPK-PGC-1α/Sirt1 and PPAR signalling pathways. This will help us better understand the benefits of flavonoids and their mechanism. Despite our positive results in animal experiments, there is still a lack of clinical trials to confirm the efficiency and safety of flavonoids in the human body. Mark found that inflammation reduces the expression of UCP-1 in mature brown adipocytes but that resveratrol partly reduced the downregulation of UCP-1 induced by IL1β [122]. Pro-inflammatory factor-induced apoptosis plays an important role in the acquisition of terminally differentiated phenotype of brown adipocytes [123]. Flavonoids may promote brown preadipocyte differentiation, inhibit apoptosis and produce inflammatory factors in BAT. Flavonoids elevate energy expenditure by activating the sympathetic nervous system and increasing UCP-1 mRNA in BAT and plasma catecholamine [124].

The signaling pathways and mechanisms whereby flavonoids promote WAT browning. SNS: sympathetic nervous system; β3-AR: β3 adrenocepter; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PKA: protein kinase A; AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; AICAR: 5-Amino-4-formamide imidazolium ribonucleotide; Sirt1: silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1; VMH: ventromedial hypothalamus; JNK: C-Jun amino-terminal kinase; T4: tetraiodothyronine; T3: triiodothyronine; NAD+: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PGC-1α: proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α; PPAR: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; WAT: white adipose tissue; BAT: brown adipose tissue; PRDM16: positive regulatory domain containing 16; UCP-1: uncoupling protein 1; HSL: hormone sensitive lipase; ACC: acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase

However, some unknown aspects and limitations remain to explored: (1) After intestinal absorption, flavonoids are metabolized in the intestinal and hepatic cells and appear as metabolites in the urine and blood [125]. In humans, the peak plasma concentrations of flavonoids absorbed and metabolized into the blood and urine are low. However, the roles of their metabolites may be different from parent compounds [126]. A potential need, therefore, is to precisely determine the lowest effective concentration of flavonoids. Another concern is whether this minimal effective concentration is obtainable after intestinal absorption and metabolism. Likewise, an important dogma would be the relative contributions of parent flavonoids and their metabolites to biological responses under considerations. (2) Additionally, the bioavailability of flavonoids is low due to limited absorption, extensive metabolism, and rapid excretion. However luckily; to date, no adverse effects have been found due to the high dietary intake of flavonoids from plant-based food in healthy people. Under special circumstances, however, like (cancer, burns and massive trauma), the benefits of promoting WAT browning by flavonoids must be weighed versus some reported adverse effects in these conditions. Further clinical trials are warranted to delineate their exact roles, safety and mechanisms. (3) Besides, some flavonoids are known to be phytoestrogens. Accordingly, although some studies found that flavonoids influence sex-hormone-dependent signaling pathways and protect against breast and prostate cancers, it is crucial to probe also whether and how they may also interfere with the synthesis and activity of such endogenous hormones [127].

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase

- AICAR:

-

5-Amino-4-formamide imidazolium ribonucleotide

- AMPK:

-

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- AOX:

-

Alternative oxidase

- ASCs:

-

Human adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- BAT:

-

Brown adipose tissue

- BE:

-

Black soybean seed coat extract

- BT:

-

Body temperature

- C/EBP:

-

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CASNA:

-

Cutaneous sympathetic nerve activity

- CIDEA:

-

Cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor alpha (DFFA)-like effector α

- CLPr:

-

Cacao liquor procyanidin

- CPT-1α:

-

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 alpha

- Cy-3-G:

-

Cyanidin-3-glucoside

- EGCG:

-

Epigallocatechin gallate

- FABP4:

-

Fatty acid-binding protein 4

- FME:

-

Fortunella margarita fruit extract

- GLUT4:

-

Translocation of glucose transporter 4

- GTEs:

-

Green tea extracts

- GVNA:

-

Gastric vagal never activity

- HFD:

-

High-fat diet

- HSL:

-

Hormone sensitive lipase

- JNK:

-

C-Jun amino-terminal kinase

- KPF:

-

Kaempferol

- LPL:

-

Lipoprotein lipase

- NAD + :

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NOB:

-

Nobiletin

- OLE:

-

Olive leaf extract

- p38 MAPK:

-

p38 mitogenactivated protein kinase

- PE:

-

Proanthocyanidin extracts

- PGC-1α:

-

Proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α

- PKA:

-

Protein kinase A

- PPAR:

-

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

- PRDM16:

-

Positive regulatory domain containing 16

- Sirt1:

-

Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1

- SNS:

-

Sympathetic nervous system

- sWAT:

-

Subcutaneous white adipose tissue

- T3:

-

Triiodothyronine

- T4:

-

Tetraiodothyronine

- TBX1:

-

T-box transcription factor 1

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TH:

-

Thyroid hormones

- TRIAC:

-

T3 metabolite triiodothyracetic acid

- TRPV1:

-

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- TRs:

-

Thyroid hormone receptors

- TSH:

-

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- UCP-1:

-

Uncoupling protein 1

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VMH:

-

Ventromedial hypothalamus

- WAT:

-

White adipose tissue

- β3-AR:

-

β3 adrenocepter

References

Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E444–52.

Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10.

Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat Med. 2013;19:10.

Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:2.

Stanford KI, Middelbeek RJ, Townsend KL, An D, Nygaard EB, Hitchcox KM, et al. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1.

Bostrom P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, et al. A PGC1-alpha-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:7382.

Lecoultre V, Ravussin E. Brown adipose tissue and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14:1.

Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Kameya T, Kawai Y, et al. Age-related decrease in cold-activated brown adipose tissue and accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Obesity. 2011;19:9.

Tiraby C, Langin D. Conversion from white to brown adipocytes: a strategy for the control of fat mass? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:10.

Giordano A, Frontini A, Cinti S. Convertible visceral fat as a therapeutic target to curb obesity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:6.

Poekes L, Lanthier N, Leclercq IA. Brown adipose tissue: a potential target in the fight against obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci. 2015;129:11.

Abdullahi A, Jeschke MG. White adipose tissue Browning: a double-edged sword. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27:8.

Harborne JB. Nature, distribution and function of plant flavonoids. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1986;213 PMID:3520585.

Hanakova Z, Hosek J, Kutil Z, Temml V, Landa P, Vanek T, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of natural Geranylated flavonoids: cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase inhibitory properties and proteomic analysis. J Nat Prod. 2017;80:4.

Chen P, Cao Y, Bao B, Zhang L, Ding A. Antioxidant capacity of Typha angustifolia extracts and two active flavonoids. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:1.

Burkard M, Leischner C, Lauer UM, Busch C, Venturelli S, Frank J. Dietary flavonoids and modulation of natural killer cells: implications in malignant and viral diseases. J Nutr Biochem. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.01.006.

Wang G, Wang JJ, Guan R, Du L, Gao J, Fu XL. Strategies to target glucose metabolism in tumor microenvironment on Cancer by flavonoids. Nutr Cancer. 2017;69:4.

Saito M, Yoneshiro T, Matsushita M. Food ingredients as anti-obesity agents. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:11.

Yuan X, Wei G, You Y, Huang Y, Lee HJ, Dong M, et al. Rutin ameliorates obesity through brown fat activation. FASEB J. 2017;31:1.

Zhang X, Zhang QX, Wang X, Zhang L, Qu W, Bao B, et al. Dietary luteolin activates browning and thermogenesis in mice through an AMPK/PGC1alpha pathway-mediated mechanism. Int J Obes. 2016;40:12.

Barbagallo I, Vanella L, Cambria MT, Tibullo D, Godos J, Guarnaccia L, et al. Silibinin regulates lipid metabolism and differentiation in functional human adipocytes. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:309 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00309.

Kang HW, Lee SG, Otieno D, Ha K. Flavonoids, potential bioactive compounds, and non-shivering thermogenesis. Nutrients. 2018;10:9.

Azhar Y, Parmar A, Miller CN, Samuels JS, Rayalam S. Phytochemicals as novel agents for the induction of browning in white adipose tissue. Nutr Metab. 2016;13:89.

Lee SG, Parks JS, Kang HW. Quercetin, a functional compound of onion peel, remodels white adipocytes to brown-like adipocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;42 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.12.018.

Rivera L, Moron R, Sanchez M, Zarzuelo A, Galisteo M. Quercetin ameliorates metabolic syndrome and improves the inflammatory status in obese Zucker rats. Obesity. 2008;16:9.

Dong J, Zhang X, Zhang L, Bian HX, Xu N, Bao B, et al. Quercetin reduces obesity-associated ATM infiltration and inflammation in mice: a mechanism including AMPKalpha1/SIRT1. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:3.

Arias N, Pico C, Teresa Macarulla M, Oliver P, Miranda J, Palou A, et al. A combination of resveratrol and quercetin induces browning in white adipose tissue of rats fed an obesogenic diet. Obesity. 2017;25:1.

Kuipers EN, Dam ADV, Held NM, Mol IM, Houtkooper RH, Rensen PCN, et al. Quercetin lowers plasma triglycerides accompanied by white adipose tissue Browning in diet-induced obese mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:6.

Ahn J, Lee H, Kim S, Park J, Ha T. The anti-obesity effect of quercetin is mediated by the AMPK and MAPK signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:4.

Zhang Y, Gu M, Cai W, Yu L, Feng L, Zhang L, et al. Dietary component isorhamnetin is a PPARgamma antagonist and ameliorates metabolic disorders induced by diet or leptin deficiency. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19288.

Bae CR, Park YK, Cha YS. Quercetin-rich onion peel extract suppresses adipogenesis by down-regulating adipogenic transcription factors and gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Sci Food Agric. 2014;94:13.

Gao M, Ma Y, Liu D. Rutin suppresses palmitic acids-triggered inflammation in macrophages and blocks high fat diet-induced obesity and fatty liver in mice. Pharm Res. 2013;30:11.

You Y, Yuan X, Liu X, Liang C, Meng M, Huang Y, et al. Cyanidin-3-glucoside increases whole body energy metabolism by upregulating brown adipose tissue mitochondrial function. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61:11 https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201700261.

Pei L, Wan T, Wang S, Ye M, Qiu Y, Jiang R, et al. Cyanidin-3-O-beta-glucoside regulates the activation and the secretion of adipokines from brown adipose tissue and alleviates diet induced fatty liver. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.018.

Matsukawa T, Villareal MO, Motojima H, Isoda H. Increasing cAMP levels of preadipocytes by cyanidin-3-glucoside treatment induces the formation of beige phenotypes in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.09.018.

You Y, Yuan X, Lee HJ, Huang W, Jin W, Zhan J. Mulberry and mulberry wine extract increase the number of mitochondria during brown adipogenesis. Food Funct. 2015;6:2.

Matsumura Y, Nakagawa Y, Mikome K, Yamamoto H, Osakabe N. Enhancement of energy expenditure following a single oral dose of flavan-3-ols associated with an increase in catecholamine secretion. PLoS One. 2014;9:11.

Watanabe N, Inagawa K, Shibata M, Osakabe N. Flavan-3-ol fraction from cocoa powder promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-13-64.

Osakabe N, Hoshi J, Kudo N, Shibata M. The flavan-3-ol fraction of cocoa powder suppressed changes associated with early-stage metabolic syndrome in high-fat diet-fed rats. Life Sci. 2014;114:1.

Nomura S, Ichinose T, Jinde M, Kawashima Y, Tachiyashiki K, Imaizumi K. Tea catechins enhance the mRNA expression of uncoupling protein 1 in rat brown adipose tissue. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:12.

Kudo N, Arai Y, Suhara Y, Ishii T, Nakayama T, Osakabe N. A single Oral Administration of Theaflavins Increases Energy Expenditure and the expression of metabolic genes. PLoS One. 2015;10:9.

Yamashita Y, Wang L, Wang L, Tanaka Y, Zhang T, Ashida H. Oolong, black and pu-erh tea suppresses adiposity in mice via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Food Funct. 2014;5:10.

Yan J, Zhao Y, Zhao B. Green tea catechins prevent obesity through modulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Sci China Life Sci. 2013;56:9.

Dulloo AG, Seydoux J, Girardier L, Chantre P, Vandermander J. Green tea and thermogenesis: interactions between catechin-polyphenols, caffeine and sympathetic activity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:2.

Varela CE, Rodriguez A, Romero-Valdovinos M, Mendoza-Lorenzo P, Mansour C, Ceballos G, et al. Browning effects of (−)-epicatechin on adipocytes and white adipose tissue. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.05.051.

Choi JH, Yun JW. Chrysin induces brown fat-like phenotype and enhances lipid metabolism in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Nutrition. 2016;32:9.

Lone J, Parray HA, Yun JW. Nobiletin induces brown adipocyte-like phenotype and ameliorates stress in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochimie. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2017.11.021.

Tsutsumi R, Yoshida T, Nii Y, Okahisa N, Iwata S, Tsukayama M, et al. Sudachitin, a polymethoxylated flavone, improves glucose and lipid metabolism by increasing mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. Nutr Metab. 2014;11:32.

Shen J, Nakamura H, Fujisaki Y, Tanida M, Horii Y, Fuyuki R, et al. Effect of 4G-alpha-glucopyranosyl hesperidin on brown fat adipose tissue- and cutaneous-sympathetic nerve activity and peripheral body temperature. Neurosci Lett. 2009;461:1.

Mulvihill EE, Allister EM, Sutherland BG, Telford DE, Sawyez CG, Edwards JY, et al. Naringenin prevents dyslipidemia, apolipoprotein B overproduction, and hyperinsulinemia in LDL receptor-null mice with diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2009;58:10.

Kim GS, Park HJ, Woo JH, Kim MK, Koh PO, Min W, et al. Citrus aurantium flavonoids inhibit adipogenesis through the Akt signaling pathway in 3T3-L1 cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:31.

Cho KW, Kim YO, Andrade JE, Burgess JR, Kim YC. Dietary naringenin increases hepatic peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor alpha protein expression and decreases plasma triglyceride and adiposity in rats. Eur J Nutr. 2011;50:2.

Takahashi Y, Ide T. Effects of soy protein and isoflavone on hepatic fatty acid synthesis and oxidation and mRNA expression of uncoupling proteins and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in adipose tissues of rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:10.

Lephart ED, Porter JP, Lund TD, Bu L, Setchell KD, Ramoz G, et al. Dietary isoflavones alter regulatory behaviors, metabolic hormones and neuroendocrine function in long-Evans male rats. Nutr Metab. 2004;1:1.

Aziz SA, Wakeling LA, Miwa S, Alberdi G, Hesketh JE, Ford D. Metabolic programming of a beige adipocyte phenotype by genistein. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61:2.

Crespillo A, Alonso M, Vida M, Pavon FJ, Serrano A, Rivera P, et al. Reduction of body weight, liver steatosis and expression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 by the isoflavone daidzein in diet-induced obesity. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:7.

Pajuelo D, Quesada H, Diaz S, Fernandez-Iglesias A, Arola-Arnal A, Blade C, et al. Chronic dietary supplementation of proanthocyanidins corrects the mitochondrial dysfunction of brown adipose tissue caused by diet-induced obesity in Wistar rats. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:2.

Zhou X, Chen S, Ye X. The anti-obesity properties of the proanthocyanidin extract from the leaves of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb.et Zucc.). Food Funct. 2017;8:–9.

Pajuelo D, Diaz S, Quesada H, Fernandez-Iglesias A, Mulero M, Arola-Arnal A, et al. Acute administration of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract modulates energetic metabolism in skeletal muscle and BAT mitochondria. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:8.

Tanida M, Tsuruoka N, Shen J, Horii Y, Beppu Y, Kiso Y, et al. Effects of flavangenol on autonomic nerve activities and dietary body weight gain in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:11.

Yamashita Y, Okabe M, Natsume M, Ashida H. Prevention mechanisms of glucose intolerance and obesity by cacao liquor procyanidin extract in high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6 mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;527:2.

Kiyofuji A, Yui K, Takahashi K, Osada K. Effects of xanthohumol-rich hop extract on the differentiation of preadipocytes. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63:6.

Yang JY, Della-Fera MA, Rayalam S, Baile CA. Effect of xanthohumol and isoxanthohumol on 3T3-L1 cell apoptosis and adipogenesis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:11.

Morimoto-Kobayashi Y, Ohara K, Takahashi C, Kitao S, Wang G, Taniguchi Y, et al. Matured hop bittering components induce thermogenesis in Brown adipose tissue via sympathetic nerve activity. PLoS One. 2015;10:6.

Kanamoto Y, Yamashita Y, Nanba F, Yoshida T, Tsuda T, Fukuda I, et al. A black soybean seed coat extract prevents obesity and glucose intolerance by up-regulating uncoupling proteins and down-regulating inflammatory cytokines in high-fat diet-fed mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:16.

Tan S, Li M, Ding X, Fan S, Guo L, Gu M, et al. Effects of Fortunella margarita fruit extract on metabolic disorders in high-fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6 mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:4.

Kamiya T, Nagamine R, Sameshima-Kamiya M, Tsubata M, Ikeguchi M, Takagaki K. The isoflavone-rich fraction of the crude extract of the Puerariae flower increases oxygen consumption and BAT UCP1 expression in high-fat diet-fed mice. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4:5.

Palmeri R, Monteleone JI, Spagna G, Restuccia C, Raffaele M, Vanella L, et al. Olive leaf extract from Sicilian cultivar reduced lipid accumulation by inducing thermogenic pathway during Adipogenesis. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:143.

Eo H, Jeon YJ, Lee M, Lim Y. Brown alga Ecklonia cava polyphenol extract ameliorates hepatic lipogenesis, oxidative stress, and inflammation by activation of AMPK and SIRT1 in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:1.

Kim KA, Yim JE. Antioxidative activity of onion Peel extract in obese women: a randomized, double-blind. Placebo Controlled Study J Cancer Prev. 2015;20:3.

Stewart LK, Soileau JL, Ribnicky D, Wang ZQ, Raskin I, Poulev A, et al. Quercetin transiently increases energy expenditure but persistently decreases circulating markers of inflammation in C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet. Metabolism. 2008;57(7 Suppl 1):S39–46.

Jung CH, Cho I, Ahn J, Jeon TI, Ha TY. Quercetin reduces high-fat diet-induced fat accumulation in the liver by regulating lipid metabolism genes. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1.

Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:7241.

Moon J, Do HJ, Kim OY, Shin MJ. Antiobesity effects of quercetin-rich onion peel extract on the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and the adipogenesis in high fat-fed rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2013.05.006.

Chua LS. A review on plant-based rutin extraction methods and its pharmacological activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150:3.

Hosseinzadeh H, Nassiri-Asl M. Review of the protective effects of rutin on the metabolic function as an important dietary flavonoid. J Endocrinol Investig. 2014;37:9.

Zhou Q, Chen K, Liu P, Gao Y, Zou D, Deng H, et al. Dihydromyricetin stimulates irisin secretion partially via the PGC-1alpha pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2015.05.036.

Bhaswant M, Fanning K, Netzel M, Mathai ML, Panchal SK, Brown L. Cyanidin 3-glucoside improves diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2015.10.006.

Tsuda T, Horio F, Uchida K, Aoki H, Osawa T. Dietary cyanidin 3-O-beta-D-glucoside-rich purple corn color prevents obesity and ameliorates hyperglycemia in mice. J Nutr. 2003;133:7.

Bhaswant M, Shafie SR, Mathai ML, Mouatt P, Brown L. Anthocyanins in chokeberry and purple maize attenuate diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Nutrition. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2016.12.009.

Assini JM, Mulvihill EE, Sutherland BG, Telford DE, Sawyez CG, Felder SL, et al. Naringenin prevents cholesterol-induced systemic inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and atherosclerosis in Ldlr(−)/(−) mice. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:3.

Yui K, Kiyofuji A, Osada K. Effects of xanthohumol-rich extract from the hop on fatty acid metabolism in rats fed a high-fat diet. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63:2.

Kirkwood JS, Legette LL, Miranda CL, Jiang Y, Stevens JF. A metabolomics-driven elucidation of the anti-obesity mechanisms of xanthohumol. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:26.

Radovic B, Hussong R, Gerhauser C, Meinl W, Frank N, Becker H, et al. Xanthohumol, a prenylated chalcone from hops, modulates hepatic expression of genes involved in thyroid hormone distribution and metabolism. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54(Suppl 2):S225–35.

Radovic B, Schmutzler C, Kohrle J. Xanthohumol stimulates iodide uptake in rat thyroid-derived FRTL-5 cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:9.

Neyrinck AM, Bindels LB, Geurts L, Van Hul M, Cani PD, Delzenne NM. A polyphenolic extract from green tea leaves activates fat browning in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.07.008.

Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Central neural pathways for thermoregulation. Front Biosci. 2011;16 PMID: 21196160.

Collins S, Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Wang H. Positive and negative control of Ucp1 gene transcription and the role of beta-adrenergic signaling networks. Int J Obes. 2010;34(Suppl 1):S28–33.

Imran KM, Yoon D, Lee TJ, Kim YS. Medicarpin induces lipolysis via activation of protein kinase a in brown adipocytes. BMB Rep. 2018;51:5.

Yamaga LY, Thom AF, Wagner J, Baroni RH, Hidal JT, Funari MG. The effect of catecholamines on the glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue demonstrated by (18) F-FDG PET/CT in a patient with adrenal pheochromocytoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2.

Parysow O, Mollerach AM, Jager V, Racioppi S, San Roman J, Gerbaudo VH. Low-dose oral propranolol could reduce brown adipose tissue F-18 FDG uptake in patients undergoing PET scans. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32:5.

Diepvens K, Westerterp KR, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Obesity and thermogenesis related to the consumption of caffeine, ephedrine, capsaicin, and green tea. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:1.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Green tea catechins, caffeine and body-weight regulation. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:1.

Turkozu D, Tek NA. A minireview of effects of green tea on energy expenditure. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:2.

Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature. 2000;404:6778.

Ribeiro MO, Bianco SD, Kaneshige M, Schultz JJ, Cheng SY, Bianco AC, et al. Expression of uncoupling protein 1 in mouse brown adipose tissue is thyroid hormone receptor-beta isoform specific and required for adaptive thermogenesis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1.

Martinez de Mena R, Scanlan TS, Obregon MJ. The T3 receptor beta1 isoform regulates UCP1 and D2 deiodinase in rat brown adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2010;151:10.

Medina-Gomez G, Calvo RM, Obregon MJ. Thermogenic effect of triiodothyroacetic acid at low doses in rat adipose tissue without adverse side effects in the thyroid axis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:4.

Lopez M, Varela L, Vazquez MJ, Rodriguez-Cuenca S, Gonzalez CR, Velagapudi VR, et al. Hypothalamic AMPK and fatty acid metabolism mediate thyroid regulation of energy balance. Nat Med. 2010;16:9.

Alvarez-Crespo M, Csikasz RI, Martinez-Sanchez N, Dieguez C, Cannon B, Nedergaard J, et al. Essential role of UCP1 modulating the central effects of thyroid hormones on energy balance. Mol Metab. 2016;5:4.

Lee JY, Takahashi N, Yasubuchi M, Kim YI, Hashizaki H, Kim MJ, et al. Triiodothyronine induces UCP-1 expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in human adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:2.

Skarulis MC, Celi FS, Mueller E, Zemskova M, Malek R, Hugendubler L, et al. Thyroid hormone induced brown adipose tissue and amelioration of diabetes in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1.

Martinez-Sanchez N, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Contreras C, Rial-Pensado E, Ferno J, Nogueiras R, et al. Thyroid hormones induce browning of white fat. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:2.

da Silva WS, Harney JW, Kim BW, Li J, Bianco SD, Crescenzi A, et al. The small polyphenolic molecule kaempferol increases cellular energy expenditure and thyroid hormone activation. Diabetes. 2007;56:3.

Schroder-van der Elst JP, van der Heide D, Kohrle J. In vivo effects of flavonoid EMD 21388 on thyroid hormone secretion and metabolism in rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:2.

van Dam AD, Kooijman S, Schilperoort M, Rensen PC, Boon MR. Regulation of brown fat by AMP-activated protein kinase. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:9 https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.2.E227.

Mulligan JD, Gonzalez AA, Stewart AM, Carey HV, Saupe KW. Upregulation of AMPK during cold exposure occurs via distinct mechanisms in brown and white adipose tissue of the mouse. J Physiol. 2007;580(Pt. 2):677–84.

Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:6.

Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:1.

Suwa M, Nakano H, Kumagai S. Effects of chronic AICAR treatment on fiber composition, enzyme activity, UCP3, and PGC-1 in rat muscles. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:3.

Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:29.

Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1alpha, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:4.

Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. PPARgamma: a nuclear regulator of metabolism, differentiation, and cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41.

Mukherjee R, Jow L, Croston GE, Paterniti JR Jr. Identification, characterization, and tissue distribution of human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) isoforms PPARgamma2 versus PPARgamma1 and activation with retinoid X receptor agonists and antagonists. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12.

Wang YX, Lee CH, Tiep S, Yu RT, Ham J, Kang H, et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell. 2003;113:2.

Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829.

Vernochet C, Peres SB, Davis KE, McDonald ME, Qiang L, Wang H, et al. C/EBPalpha and the corepressors CtBP1 and CtBP2 regulate repression of select visceral white adipose genes during induction of the brown phenotype in white adipocytes by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:17.

Qiang L, Wang L, Kon N, Zhao W, Lee S, Zhang Y, et al. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Ppargamma. Cell. 2012;150:3.

Walczak R, Tontonoz P. Setting fat on fire. Nat Med. 2003;9:11.

Rachid TL, Penna-de-Carvalho A, Bringhenti I, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. PPAR-alpha agonist elicits metabolically active brown adipocytes and weight loss in diet-induced obese mice. Cell Biochem Funct. 2015;33:4.

Hondares E, Rosell M, Diaz-Delfin J, Olmos Y, Monsalve M, Iglesias R, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) induces PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha) gene expression and contributes to thermogenic activation of brown fat: involvement of PRDM16. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:50.

Nohr MK, Bobba N, Richelsen B, Lund S, Pedersen SB. Inflammation downregulates UCP1 expression in Brown adipocytes potentially via SIRT1 and DBC1 interaction. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:5.

Miranda S, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Revuelta-Cervantes J, Rondinone CM, Valverde AM. Beneficial effects of PTP1B deficiency on brown adipocyte differentiation and protection against apoptosis induced by pro- and anti-inflammatory stimuli. Cell Signal. 2010;22:4.

Nakagawa Y, Ishimura K, Oya S, Kamino M, Fujii Y, Nanba F, et al. Comparison of the sympathetic stimulatory abilities of B-type procyanidins based on induction of uncoupling protein-1 in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and increased plasma catecholamine (CA) in mice. PLoS One. 2018;13:7.

Rothwell JA, Urpi-Sarda M, Boto-Ordonez M, Llorach R, Farran-Codina A, Barupal DK, et al. Systematic analysis of the polyphenol metabolome using the phenol-explorer database. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60:1.

Lotito SB, Zhang WJ, Yang CS, Crozier A, Frei B. Metabolic conversion of dietary flavonoids alters their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:2.

Ko KP. Isoflavones: chemistry, analysis, functions and effects on health and cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:17.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly completed in the Department of Orthopaedics, Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The authors would like to thank HUST for the use of the research facilities and the support through the NSFC funds.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81070691).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XJZ, XL and SLH developed the concept and designed the review. XJZ, XL, FJG, and HF performed literature research and summarized the data. FL and AMC performed the data analysis and edited the manuscript. The review was written by XJZ and SLH. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Li, X., Fang, H. et al. Flavonoids as inducers of white adipose tissue browning and thermogenesis: signalling pathways and molecular triggers. Nutr Metab (Lond) 16, 47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-019-0370-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-019-0370-7