Abstract

Background

Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO) is responsible for the progression of the kynurenine pathway. This pathway has been implicated in the pathophysiology of inflammation-induced depression in which conventional antidepressants are not effective. It has been reported that granulocyte-macrophage stimulating factor (GM-CSF) could interfere with the induction of IDO in septic patients. We hypothesized that GM-CSF could exert antidepressant effects through IDO downregulation in a model for acute inflammation-induced depression.

Methods

To produce the model, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (0.83 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally to mice. It has been well documented that LPS mediates IDO overexpression through TLR4/NF-ĸB signaling. In the treatment group, mice received GM-CSF (30 μg/kg, i.p.) thirty minutes prior to LPS injection. A validated selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine (30 mg/kg i.p.), was also administered to an experimental group 30 min prior to LPS. Depressive-like behaviors were evaluated based on the duration of immobility in the forced swim test. To confirm that GM-CSF interferes with IDO induction in LPS treated mice, real-time PCR was used to quantify IDO mRNA expression. Furthermore, in order to study whether GM-CSF inhibits the TLR4/NF-ĸB signaling pathway, we measured levels ofpNF-ĸB and TLR4 by western blotting.

Results

GM-CSF demonstrated significant antidepressant activity in the presence of LPS on immobility (p < .001) and latency (p = .010) times in the forced swim test. In contrast, fluoxetine did not show any antidepressant activity on either immobility (p = .918) or latency (p = .566) times. Furthermore, GM-CSF inhibited the increase in IDO mRNA (p = .032) and protein (p = .016) expression as a result of LPS administration. A similar trend was observed for TLR4 (p = .042) and pNF-ĸB (p = .026) expression as both proteins showed reduced expression levels in the GM-CSF-pretreated group compared to the untreated (LPS) group.

Conclusion

Our results propose a promising antidepressant effect for GM-CSF possibly through the downregulation of IDO expression. This remedying effect of GM-CSF could be attributed to decreased amounts of TLR4 and active NF-ĸB in the treated mice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammation-induced depression is a debilitating psychiatric disorder which is caused by neurodegenerative metabolites in the CNS [1]. This type of depression is refractory to conventional medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) because such treatments fail to affect the main trigger of the disease [2]. One of the most important pathways affected by the CNS inflammatory conditions is tryptophan metabolism [3]. Some catabolic metabolites of tryptophan in the kynurenine pathway are considered neurotoxic. One such metabolite, quinolinic acid, is the agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor that leads to increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4]. This oxidative stress may result in neuronal degeneration in the hippocampus and exacerbate depressive behaviors [5]. Aside from direct neurotoxic effects of ROS, they can induce well-known factors involved in depression such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2) [6]. Inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α have been shown to enhance this pathway in cultured microglia by potentiating the expression of the pathway’s main controller enzyme, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), through STAT1 activation [7]. In a similar manner, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) upregulate IDO levels through activating the TLR4/NF-ĸB signaling pathway [8]. A major site for IDO activation following LPS administration is the hippocampus [9, 10]. Importantly, the hippocampus is one of the most vulnerable areas of the brain to quinolinic acid [11] while simultaneously being the site for the highest production of neurotoxic metabolites of the kynurenine pathway following LPS challenge [12]. As a major site for major depressive disorder, inflammation and IDO activation in the hippocampus have been associated with depressive-like behaviors [13, 14]. Due to its mechanism of action, LPS is commonly used to induce acute inflammation-induced depressive-like behaviors in animal models in order to introduce novel therapeutic drugs [9].

Granulocyte-macrophage stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is well known for its effects on myeloid progenitor cells. Effects of GM-CSF are not confined to the bone marrow as it is reported to be a neuroprotective factor decreasing dementia [15]. In addition, it has demonstrated promising effects on increasing neuronal plasticity in animal stroke models [16]. These neuroprotective activities have been shown to result from decreased microglial activation, increased regulatory T cell activity, and increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) production [17, 18]. The GM-CSF receptor is composed of a specific α-chain (GM-CSFRα) and a β-chain which is also present in IL-3 and IL-5 receptors. GM-CSFRα expression is observed in various regions of the murine brain including the cortex and hippocampus [19]. Several signaling pathways have been reported to be activated by GM-CSF both in neurons and glial cells, including the JAK/STAT, MAP kinase, Akt/mTOR, and Bcl-2- and Bcl-xL-activating pathways [20,21,22,23,24,25].

In accordance with our study, it has been reported that GM-CSF treatment can reduce IDO activity and tryptophan catabolism in patients with septic shock [26]. We hypothesize that GM-CSF treatment can ameliorate depressive-like behaviors in the LPS-induced model of acute inflammation-induced depression in mice. To investigate whether the tryptophan catabolism pathway mediated the observed effects, IDO mRNA expression levels were assessed using real-time PCR. Furthermore, NF-ĸB activation, as determined by the phosphorylation of the p65 subunit, and TLR4 expression proteins were studied to investigate the signaling pathway involved.

Methods

Animals

We used adult male NMRI mice (Department of Pharmacology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences), weighing 20–25g. All experimental animals were maintained under standard housing conditions of temperature (21–23 °C), humidity (55%), and light/dark cycle (12-h light/dark), and had access to water and food ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the standards of animal care determined by the Council of Laboratory Animals of the Experimental Medicine Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Drugs and experimental groups

Our study consisted of 6 experimental groups. In the first group (LPS), mice were only injected with LPS (0.83 mg/Kg, i.p.) from Escherichia Coli O55:B5 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in order to induce depressive behaviors. This dose of LPS had been determined to result in depressive-like behaviors in mice after 24 h by previous studies [9]. To demonstrate the unresponsiveness of this depression model to conventional SSRIs, the second group (LPS + Flx) received fluoxetine (30 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min prior to LPS injection. In our third group (LPS + GM-CSF), GM-CSF (Peprotech, USA) was administered (30 μg/kg, i.p.) 30 min before LPS injection. A dose of 30 μg/kg has been shown to pass through the blood–brain barrier and exert neurotrophic and was confirmed to be effective in our dose-response studies (data not shown) [21, 27, 28]. Two other groups received GM-CSF (GM-CSF) or fluoxetine (Flx) followed by normal saline instead of LPS. All drugs were dissolved in normal saline (0.9%). The control group (control) was only injected with normal saline at 5 ml/kg (i.p).

Behavioral assays

Depressive-like behaviors were measured using the forced swim test (FST) for mice 24 h after LPS administration. Increased immobility times in this test are considered to be indicative of depression [29]. Animals undergoing forced swimming were placed in a 25-cm-high open cylinder containing 19 cm of tap water at 25 °C. The immobility time of each mouse was calculated during the last 4 min of a 6-min test recording, allowing for an initial 2-min pretest period [30]. Latency times were measured from the beginning of this 4-min period. No climbing or diving activity was observed throughout the tests. Therefore, swimming times, which are complementary to immobility times, are not presented in the figures.

The open field test was used to ensure that alterations in FST immobility duration were not related to changes in locomotor function. For this test, the floor of an acrylic plastic box (50 × 50 × 30 cm) was divided into 12 equal squares. The animals were gently placed in one of the corner squares, and locomotor activity was measured by counting the number of gridline crossings and duration of mobility during a 5-min period. All assessments were performed by a well-trained observer blind to the experiment. The mice in all experimental groups were determined to have normal locomotor ability just before the FST (Fig. 1b, c).

Comparison of the forced swim test results between study groups. For LPS treatment, 1 indicates administration while 0 indicates no administration. When combined with other treatments, LPS (0.83 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 30 min after either GM-CSF (30 μg kg, i.p.) or fluoxetine (30 mg/kg, i.p.). Statistical significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons with the Tukey post hoc test. a The timeline of our experimental process. b Changes in mobility times in the OFT were not significant following fluoxetine (p = .499) or GM-CSF (p = .660) treatment regardless of LPS administration. c Changes in the number of gridline crossings were not significant following fluoxetine (p = .957) or GM-CSF (p = .929) treatment regardless of LPS administration. d Changes in immobility times in the FST were not significant following fluoxetine treatment regardless of LPS administration (p = .918). In contrast, GM-CSF treatment showed a significant interaction with LPS administration (p < .001). GM-CSF decreased immobility times significantly when followed by LPS administration (p < .001) but showed no effect when used alone (p = .940). e Latency times were measured from the beginning of the 4-min test period. Changes in latency times were not significant following fluoxetine treatment regardless of LPS administration (p = .322). However, GM-CSF treatment showed a significant interaction with LPS administration (p < .001). GM-CSF decreased latency times significantly when followed by LPS administration (p < .001) but showed no effect when used alone (p = .096)

Real-time PCR

Immediately after, the FST test, animals were decapitated and their hippocampi were rapidly dissected on an ice-cold surface and were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. After tissue homogenization, total cellular RNA was extracted in Trizol reagent. One microgram of total mRNA was reverse transcribed using cDNA kits. Specific mRNAs were amplified using the following primers: GAPDH as the housekeeping gene (Forward: TCAGAGCAAGAGAGGCATCC; Reverse: GGTCATCTTCTCACGGTTGG) and IDO (Forward: CATCAAGACCCGAAAGCAC; Reverse: CACGAAGTCACGCATCCTCT). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the Rotorgene 3000 thermocycler. Cycling conditions were consistent with previous studies [31]. Samples were run in triplicate and the 2−ΔΔCt method was used to assess the mRNA expression fold-change in comparison to the control group.

Western blotting

Mice hippocampi were homogenized in lysis buffer consisting of TRIS-HCl, SDS, DTT, glycerol, and NP40. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were used for SDS-PAGE. Ten micrograms of protein was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and moved onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) (Millipore (Germany)) membranes. Membranes were blocked for 120 min with 5% non-fat skimmed milk and incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight: TLR4, pNF-κB (p65), NF-κB, IDO1, GAPDH, and β-actin. All antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Membranes were then washed 3 times with TBST (TBS+ tween 80) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized using the BM Chemiluminescence Western Blotting Kit acquired from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany) and were detected using a gel documentation system. An open-source image-processing program, ImageJ, was used to quantify the optical densities of each band. The relative expressions of TLR4 and pNF-κB/total NF-κB were calculated and compared to the β-actin (TLR4 and pNF-κB/total NF-κB) or GAPDH (IDO1) as well as the control group.

Statistics

The effects of treatment combinations on motor function in the open field and depressive-like behaviors forced swim tests were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. Due to the unbalanced number of subjects in each group, a type-III test was used for the combination of LPS and GM-CSF following the observation of a significant interaction between the two treatments while a type-II test was used for the combination of LPS and Flx due to the lack of a significant interaction [32]. The underlying assumptions of two-way ANOVA were validated for all data using the Levene and Shapiro-Wilk tests except for latency times in the experiment studying the combination of LPS and Flx. In this experiment, the residuals of the data were found not to be normally distributed. However, this may cause an only slight increase in type I error whereas our test results were negative. In addition, the overall robustness of two-way ANOVA against violations of normality [33] led us to not use a non-parametric test in this case. The results from the open field test were also analyzed using two-way ANOVA. IDO mRNA expression levels, and pNF-κB/total NF-κB and TLR4 expression were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons between groups. The underlying assumptions of ANOVA were upheld in these comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.5.1.

Results

GM-CSF abrogates depressive-like behaviors in the forced swim test

Motor function, immobility, and latency times were compared between study groups of 4–8 mice. In the OFT, changes in mobility times and number of gridline crossings were not significant following fluoxetine (p = .499, p = .957, respectively) or GM-CSF (p = .660, p = .929, respectively) pretreatment regardless of LPS administration as determined by two-way ANOVA (Fig. 1b, c).

In the FST, a two-way ANOVA was conducted to analyze the effects of LPS and GM-CSF on depressive-like behaviors. There was a statistically significant interaction between the effects of GM-CSF and LPS on immobility time (F (1, 22) = 19.98, p < .001) and latency time (F (1, 22) = 16.44, p < .001). Simple main effects analysis showed that GM-CSF decreased immobility (p < .001) and latency times (p < .001) significantly when administered prior to LPS while showing no effect when not followed by LPS administration (p = .940 and p = .096, respectively) (Fig. 1d, e). In contrast, no interaction between LPS and Flx were observed in either FST immobility time (F (1, 19) = .00, p = .996) or FST latency time (F (1, 19) = 1.03, p = .322). Furthermore, main effects analysis showed significant effects for LPS on both immobility time (F (1, 19) = 37.73, p < .001) and latency time (F (1, 19) = 193.60, p < .001) while Flx pretreatment demonstrated no significant effect on either immobility (F (1, 19) = .01, p = .918) or latency (F (1, 19) = 2.13, p = .161) (Fig. 1d, e). These data indicate that GM-CSF treatment almost completely nullifies the effects of LPS administration on depressive-like behaviors.

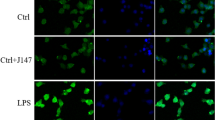

IDO expression is downregulated in GM-CSF-treated mice hippocampi

To assess the activity of the kynurenine pathway, we measured IDO mRNA levels and protein levels in mice hippocampi. Each study group consisted of 3–5 mice. As shown in Fig. 2b, expression of IDO mRNA significantly differed between the three groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(2,11) = 25.56, p < .001). All pairwise comparisons were significantly based on the Tukey post hoc analysis (control/LPS: 4.09 ± 1.55, p < .001; control/GM-CSF: 2.50 ± 1.55, p = .003; LPS/GM-CSF: 1.59 ± 1.46, p = .032).

Comparison of IDO mRNA and protein expression between study groups. The LPS + GM-CSF group were pretreated with GM-CSF (30 μg kg, i.p.) 30 min prior to LPS injection (0.83 mg/kg, i.p.). Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons with the Tukey post hoc test and is depicted in both graphs as *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. a The bands observed for each individual mouse in the western blot analysis of IDO. b IDO mRNA expression was significantly different between the three groups (p < .001). All pairwise comparisons were significant (control/LPS: p < .001; control/GM-CSF: p = .003; LPS/GM-CSF: p = .032). c IDO protein expression was significantly different between the three groups (p < .001). LPS significantly increased IDO expression (p = .005) while GM-CSF pretreatment inhibited this increase significantly (p = .016)

IDO protein levels were also significantly different between the study groups (F (2, 6) = 15.09, p < .01). A Tukey post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the control and LPS groups (2.86 ± 1.67, p = .005) and between the LPS and LPS + GM-CSF groups (− 2.20 ± 1.67, p = .016). The difference between the control and GM-CSF groups was not significant (.65 ± 1.67, p = .497) (Fig. 2c). Therefore, GM-CSF decreases LPS-induced IDO mRNA and protein expression.

Antidepressant effect of GM-CSF is potentially mediated by inhibiting LPS-induced activation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway

The expression levels of TLR4, pNF-κB, and total NF-κB in LPS and LPS + GM-CSF-treated mice were compared to the control group. For the TLR4 study, each study group consisted of 15 mice which were aggregated into three samples for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 3a). In the NF-κB study, each lane contained a single hippocampal extract (Fig. 3b). There was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA for TLR4 (F (2, 6) = 5.83, p = .039) and pNF-κB/total NF-κB (F (2, 6) = 10.76, p = .010). A Tukey post hoc analysis revealed that expression levels of both TLR4 (− .93 ± .89, p = .042) and pNF-κB/total NF-κB (− 2.16 ± 1.51, p = .011) were significantly lower in GM-CSF-treated mice compared to the untreated (LPS) groups. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the GM-CSF-treated and control groups for either TLR4 (− .17 ± .89, p = .835) or pNF-κB/total NF-κB (− .45 ± 1.51, p = .654) (Fig. 3c).

Comparison of TLR4 expression and NF-κB activation between study groups. The LPS + GM-CSF group were pretreated with GM-CSF (30 μg kg, i.p.) 30 min prior to LPS injection (0.83 mg/kg, i.p.). Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons with the Tukey post hoc test and is depicted in both graphs as *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. a The TLR4 and β-actin bands observed for two of the three groups. Each group consisted of the aggregate of 5 mice hippocampi. b NF-κB expression and activation in mice hippocampi. Each lane contains the extract of a single mouse hippocampus. c The differences between the three groups were significant for both proteins (TLR4: p = .039; pNF-κB/total NF-κB: p = .010). GM-CSF pretreatment decreased TLR4 (p = .042) and pNF-κB (p = .011) expression significantly compared to the groups only receiving LPS

Discussion

Based on our results, GM-CSF showed novel promising antidepressant effects in a validated mouse model of inflammatory depression. Improvements in mice depressive-like behaviors were demonstrated by the reduction of immobility times in the FST test. Furthermore, the mechanism underlying our treatments was investigated by assessing IDO mRNA and TLR4 expression and NF-κB activation. Our results were consistent with previous studies which had indicated that LPS induces IDO expression through an upregulation of active pNF-κB and TLR4 in the mice hippocampi [8]. However, the suppressant effects of GM-CSF on TLR4, NF-κB activation, and hence the kynurenine pathway are demonstrated for the first time.

Importantly, the effects observed here may not be attributed to endogenous GM-CSF secretion in response to LPS administration. LPS injection has been reported to increase GM-CSF serum levels during the first 10 h as an inflammatory response only at high doses (3 mg/kg). Following the initial elevation, GM-CSF levels gradually decrease to baseline levels at 24 h post-injection [34, 35]. Furthermore, the elevation of serum GM-CSF levels has not been detected at different time points after LPS administration at a similar dose to our study [36]. Therefore, it may be concluded that the results observed in our study are mainly due to the exogenous GM-CSF administration. Nevertheless, administration of GM-CSF antagonists or use of GM-CSF knock-out (KO) mice may have enhanced the interpretation of our results. However, GM-CSF antagonists are not commercially available peptides and they are usually synthesized by individual laboratories. Furthermore, the most important obstacle for administering these antagonists in our study is their inability to pass the blood–brain barrier as they are actually large GM-CSF neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, as mentioned, endogenous levels of GM-CSF seem to not play an important role in the results observed in our study; therefore, reducing the need for KO mice to some extent. These factors, combined with limitations in access to KO mice, forced us to forgo the use of these elements. Studies on the interactions of GM-CSF, the TLR4/NF-κB signaling system, and inflammation in general have produced seemingly contradictory results. Previous studies have reported that the GM-CSF receptor (GMR) triggers NF-κB activation in TF1 cells which are completely dependent on GM-CSF for growth [37]. Moreover, In one study, GM-CSF has shown pro-inflammatory functions in LPS-treated microglial cells in culture [38]. In the context of autoimmune diseases, GM-CSF has shown differing immunomodulatory (in diabetes type I and Crohn’s disease) and immunostimulatory (in rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis) effects [39,40,41,42]. Interestingly, a previous study by Kosloski et al. had shown both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory changes, including TLR4 upregulation, in the mRNA expression profiles of mice substantia nigra following GM-CSF treatment. It is clear, therefore, that the biological effects of GM-CSF on inflammation are highly dependent on the microenvironment surrounding its site of action. Our study focuses on tryptophan catabolism in the hippocampus as it is the principal site damaged in neurodegenerative depression. Furthermore, we focused on IDO activation and tryptophan catabolism as a direct mediator of neuronal injury and degeneration regardless of the inflammatory state.

Evidently, IDO activation may be achieved through various pathways. One such pathway in epithelial cells is activated in response to inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ and TNFɑ through JAK/STAT1 [43]. However, in one study, IDO expression remained unchanged in an animal model of cerebral ischemia in IFNγ−/− mice compared with the wild types [44]. Another reported pathway for induction of IDO expression is the P38/MAPK pathway in peripheral mononuclear cells treated with LPS [8]. In our study, pP38 was not detected in the cortical and hippocampal tissues of any experimental group (data not shown). One important IDO-activating pathway involves pro-inflammatory cytokines which are stimulated by LPS challenge [12]. In general, GM-CSF is considered to promote inflammation and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β in immune cells [45]. The production of IL-1β by immune cells is also boosted through synergism of GM-CSF and LPS [46]. Furthermore, GM-CSF has been identified to be a major driver of inflammation in a rat model for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [47]. On the other hand, no significant changes in IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α were identified in the study by Kosloski et al. [17]. As a result, it does not seem plausible that attenuation of IDO activity following GM-CSF administration would be due to a reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, TLR4/NF-κB signaling appears to be the most promising route for IDO elevation in the hippocampus of mice undergoing systemic LPS administration and consequent tryptophan catabolite formations.

Consistent with previous studies, animals receiving fluoxetine treatment before LPS administration did not show any improvement in depressive-like behaviors [48]. Such resistance to SSRI-therapy is also seen in 10–30% of patients with depression [2]. Interestingly, antidepressant-resistant patients have been shown to have higher levels of systemic inflammation [49]. Since systemic inflammation may in turn induce neurodegeneration [50], it could be postulated that treatment-resistant depression is more than just a simple depletion of neurotransmitters. The major problem underlying the disease is the degeneration of hippocampal neurons which are responsible for mood regulation. Importantly, GM-CSF has shown a neuroprotective effect in addition to (or, as a result of) its anti-inflammatory properties in models of spinal cord injury [51, 52]. These effects have also been observed in animal models of Parkinson’s disease [17, 53]. This might indicate that the neuroprotective effects of GM-CSF are not solely through its inhibitory effects on IDO and neurotoxic metabolite formation. For example, GM-CSF may induce BDNF production which would lead to improved functional recovery and regeneration of neurons following a CNS injury [52]. These findings may be in line with our study as GM-CSF treatment was able to completely prevent the formation of depressive-like behaviors even though IDO levels still increased upon LPS administration compared to the control group. GM-CSF is currently administered as a chemotherapeutic drug for neutropenia under the generic name Sargoramostim or Leukine. In further studies, the clinical utility of administering GM-CSF for refractory depression may be considered [54].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we introduced GM-CSF as an optimal agent for treating depressive-like behaviors in an LPS-induced model of depression in mice. The mechanism underlying this model of acute inflammation-induced depression and our findings on GM-CSF interference with this pathway are depicted in Fig. 4.

Availability of data and materials

All the necessary data is included in the article. Further data will be shared by request.

Abbreviations

- FST:

-

Forced swim test

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte-macrophage stimulating factor

- IDO:

-

Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- NMDA:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SSRIs:

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

References

Kohler O, et al. Inflammation in depression and the potential for anti-inflammatory treatment. Current neuropharmacology. 2016;14(7):732–42.

Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient preference and adherence. 2012;6:369–88.

Oxenkrug GF. Tryptophan kynurenine metabolism as a common mediator of genetic and environmental impacts in major depressive disorder: the serotonin hypothesis revisited 40 years later. The Israel journal of psychiatry and related sciences. 2010;47(1):56–63.

Kubicova L, Hadacek F, Chobot V. Quinolinic acid: neurotoxin or oxidative stress modulator? Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(11):21328–38.

Michel TM, Pulschen D, Thome J. The role of oxidative stress in depressive disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(36):5890–9.

Salim S. Oxidative stress and psychological disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2014;12(2):140–7.

Sarkar SA, et al. Induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by interferon-gamma in human islets. Diabetes. 2007;56(1):72–9.

Fujigaki H, et al. The signal transducer and activator of transcription 1alpha and interferon regulatory factor 1 are not essential for the induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by lipopolysaccharide: involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways, and synergistic effect of several proinflammatory cytokines. J Biochem. 2006;139(4):655–62.

O'Connor JC, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Molecular psychiatry. 2009;14(5):511–22.

Fu X, et al. Central administration of lipopolysaccharide induces depressive-like behavior in vivo and activates brain indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase in murine organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:43.

Schwarcz R, Kohler C. Differential vulnerability of central neurons of the rat to quinolinic acid. Neurosci Lett. 1983;38(1):85–90.

Parrott JM, Redus L, O’Connor JC. Kynurenine metabolic balance is disrupted in the hippocampus following peripheral lipopolysaccharide challenge. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):124.

Xu Y, et al. Inflammation and increased IDO in hippocampus contribute to depression-like behavior induced by estrogen deficiency. Behavioural Brain Research. 2015;288:71–8.

Maes M, et al. The inflammatory & neurodegenerative (I&ND) hypothesis of depression: leads for future research and new drug developments in depression. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2009;24(1):27–53.

Shang DS, et al. Intracerebral GM-CSF contributes to transendothelial monocyte migration in APP/PS1 Alzheimer's disease mice. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2016;36(11):1978–91.

Theoret JK, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor treatment results in recovery of motor function after white matter damage in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;43(1):17–24.

Kosloski LM, et al. GM-CSF induces neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory responses in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine intoxicated mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;265(1-2):1–10.

Bombeiro AL, Pereira BTN, de Oliveira ALR. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor improves mouse peripheral nerve regeneration following sciatic nerve crush. Eur J Neurosci. 2018;48(5):2152–64.

Krieger M, et al. The hematopoietic cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor is important for cognitive functions. Scientific Reports. 2012;2:697.

Mausberg AK, Jander S, Reichmann G. Intracerebral granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces functionally competent dendritic cells in the mouse brain. Glia. 2009;57(12):1341–50.

Schabitz WR, et al. A neuroprotective function for the hematopoietic protein granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(1):29–43.

Choudhury ME, et al. A cytokine mixture of GM-CSF and IL-3 that induces a neuroprotective phenotype of microglia leading to amelioration of (6-OHDA)-induced Parkinsonism of rats. Brain and behavior. 2011;1(1):26–43.

Liva SM, et al. Signal transduction pathways induced by GM-CSF in microglia: significance in the control of proliferation. Glia. 1999;26(4):344–52.

Legacy J, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes regeneration of retinal ganglion cells in vitro through a mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91(6):771–9.

Choi JK, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor shows anti-apoptotic activity via the PI3K-NF-kappaB-HIF-1alpha-survivin pathway in mouse neural progenitor cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49(2):724–33.

Schefold JC, et al. Treatment with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is associated with reduced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity and kynurenine pathway catabolites in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(3):164–71.

McLay RN, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor crosses the blood--brain and blood--spinal cord barriers. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 11):2083–91.

Kelso ML, et al. Neuroprotective Activities of Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor Following Controlled Cortical Impact. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2015;0:162–73.

Can, A., et al., The mouse forced swim test. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, 2012(59): p. e3638-e3638.

Yankelevitch-Yahav R, et al. The forced swim test as a model of depressive-like behavior. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2015;(97):52587.

Jenabian M-A, et al. Correction: distinct tryptophan catabolism and Th17/Treg balance in HIV progressors and elite controllers. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/11698dd2-0bc1-4fe0-ad92-b161b5594e81.

Langsrud Ø. ANOVA for unbalanced data: use type II instead of type III sums of squares. Statistics and Computing. 2003;13(2):163–7.

Blanca MJ, et al. Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema. 2017;29(4):552–7.

Erickson MA, Banks WA. Cytokine and chemokine responses in serum and brain after single and repeated injections of lipopolysaccharide: multiplex quantification with path analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(8):1637–48.

Tiegs G, et al. Potentiation by granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor of lipopolysaccharide toxicity in mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(6):2616–22.

Reed JA, et al. GM-CSF action in the CNS decreases food intake and body weight. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115(11):3035–44.

Ebner K, et al. GMCSF activates NF-kappaB via direct interaction of the GMCSF receptor with IkappaB kinase beta. Blood. 2003;102(1):192–9.

Parajuli, B., et al., GM-CSF increases LPS-induced production of proinflammatory mediators via upregulation of TLR4 and CD14 in murine microglia. Journal of neuroinflammation, 2012. 9: p. 268-268.

Knoop J, et al. GM-CSF producing autoreactive CD4(+) T cells in type 1 diabetes. Clin Immunol. 2018;188:23–30.

Roth L, et al. Sargramostim (GM-CSF) for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:Cd008538.

Avci AB, Feist E, Burmester GR. Targeting GM-CSF in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(4 Suppl 98):39–44.

Croxford AL, Spath S, Becher B. GM-CSF in Neuroinflammation: Licensing Myeloid Cells for Tissue Damage. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(10):651–62.

Shirey KA, et al. Upregulation of IFN-γ Receptor Expression by Proinflammatory Cytokines Influences IDO Activation in Epithelial Cells. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2006;26(1):53–62.

Hoshi M, et al. Marked increases in hippocampal neuron indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase via IFN-gamma-independent pathway following transient global ischemia in mouse. Neurosci Res. 2009;63(3):194–8.

Becher B, Tugues S, Greter M. GM-CSF: from growth factor to central mediator of tissue inflammation. Immunity. 2016;45(5):963–73.

Khameneh HJ, et al. GM-CSF Signalling boosts dramatically IL-1 production. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(7):e23025.

Croxford AL, et al. The cytokine GM-CSF drives the inflammatory signature of CCR2+ monocytes and licenses autoimmunity. Immunity. 2015;43(3):502–14.

Wang Y, et al. LPS inhibits the effects of fluoxetine on depression-like behavior and hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(8):1831–5.

Haroon E, et al. Antidepressant treatment resistance is associated with increased inflammatory markers in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;95:43–9.

Huang C, et al. Evidence of the impact of systemic inflammation on neuroinflammation from a non-bacterial endotoxin animal model. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):147.

Huang X, et al. GM-CSF inhibits glial scar formation and shows long-term protective effect after spinal cord injury. J Neurol Sci. 2009;277(1-2):87–97.

Bouhy D, et al. Delayed GM-CSF treatment stimulates axonal regeneration and functional recovery in paraplegic rats via an increased BDNF expression by endogenous macrophages. Faseb j. 2006;20(8):1239–41.

Mangano EN, et al. Granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor protects against substantia nigra dopaminergic cell loss in an environmental toxin model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2011;43(1):99–112.

Mehta HM, Malandra M, Corey SJ. G-CSF and GM-CSF in Neutropenia. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2015;195(4):1341–9.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Experimental Medicine Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (grant no. 97-02-158-39143).

Funding

This study was financially supported by Experimental Medicine Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (grant no. 97-02-158-39143).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH and MS contributed equally to the study conception, design, and preparation of the manuscript. RM and HY contributed to performing the experiments. AD supervised the study and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the experiments were in accordance with the guidelines of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hemmati, S., Sadeghi, M.A., Mohammad Jafari, R. et al. The antidepressant effects of GM-CSF are mediated by the reduction of TLR4/NF-ĸB-induced IDO expression. J Neuroinflammation 16, 117 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-019-1509-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-019-1509-1