Abstract

Background

Traumatic brain injury can trigger chronic neuroinflammation, which may predispose to neurodegeneration. Animal models and human pathological studies demonstrate persistent inflammation in the thalamus associated with axonal injury, but this relationship has never been shown in vivo.

Findings

Using [11C]-PK11195 positron emission tomography, a marker of microglial activation, we previously demonstrated thalamic inflammation up to 17 years after traumatic brain injury. Here, we use diffusion MRI to estimate axonal injury and show that thalamic inflammation is correlated with thalamo-cortical tract damage.

Conclusions

These findings support a link between axonal damage and persistent inflammation after brain injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a risk factor for dementia [1], and survivors may deteriorate years after their injury [2]. However, the mechanisms relating TBI to neurodegeneration are unclear [1]. An important factor is likely to be neuroinflammation in the form of glial activation triggered by the TBI and which can persist for many years [3]. Chronic activation of microglia is implicated in many neurodegenerative disorders [4]. Previously, using [11C]-PK11195 (PK) PET, a marker of the translocator protein (TSPO) expressed by activated microglia, we observed inflammation in the thalamus up to 17 years after TBI [3]. Why thalamic inflammation persists, remote from sites of focal injury, remains uncertain.

The spatial pattern of microglial activation following brain injury may relate to the white matter architecture of the CNS [5, 6]. Experimental axotomy induces microglial activation remote from the primary lesion site [5]. The thalamus is highly connected and shows chronic inflammation after central and peripheral nerve damage [5, 7]. After stroke, microglial activation is seen at the primary lesion but later emerges in projection areas including the thalamus [8, 9]. Following TBI, axons in white matter are highly susceptible to damage, making traumatic axonal injury (TAI) one of the most common pathologies of TBI [10]. Together, these observations suggest thalamic inflammation following TBI may result from the high density of connectivity between the thalamus and damaged axons.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can map the structure of thalamo-cortical white matter tracts using probabilistic tractography [11], but TBI patients with TAI pose challenges to these methods [12]. Recently, we developed a template-based approach for more robust estimation of thalamo-cortical tract integrity after TBI [12].

Hypothesis

Here, we combine this approach with PK PET to test the hypothesis that chronic thalamic inflammation after TBI can be explained by thalamo-cortical white matter damage.

Methods

Ten patients with a history of moderate-severe TBI (Mayo classification) (mean age ± s.d. 43 ± 5.3 years, range 36–54; mean time since injury ± s.d. 6.2 ± 5.3 years, range 0.9–17) had PK PET and structural MRI scans including DTI (see [3] for details). Two age-matched healthy control groups were used. Seven controls (mean age 46 ± 4.0, range 42–50) had PET and structural MRI. Thirteen controls (41.8 ± 6.6, 35–56) of similar premorbid intellectual ability had MRI including DTI. The project was approved by Hammersmith and Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Research Ethics Committee. All participants gave informed consent.

Standard MRI T1 and DTI protocols were used (see [3]). For DTI analysis, we used a method for assessing thalamo-cortical white matter connections that is robust to the presence of TAI [12]. We combined ten thalamo-cortical tracts, previously defined in healthy controls using probabilistic tractography, into a single region of interest (ROI) (see Fig. 1c for example of one tract, and [12]). A mask of cortico-cortical tracts through the body of the corpus callosum was used as a control (from [13]), since these tracts were not connected to the thalamus. Voxel-wise maps of fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of directionality of water flow along white matter tracts and hence their integrity, were calculated, and FA maps were skeletonised [14], leaving the central section of tracts, to minimise partial volume effects (see [12]). We calculated the mean FA of voxels within the ROIs and of all voxels in the skeleton. The B0 data for one patient contained an image artefact, so their DTI data were excluded.

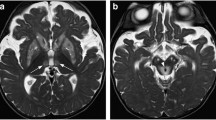

Increased thalamic microglial activation and white matter damage in TBI. a Statistical parametric maps (reproduced from [3]) rendered onto a standard T1 MRI image showing areas of significantly increased [11C]-PK11195 (PK) binding potentials (BP) in the TBI patients relative to controls. Bilateral increases in PK binding are seen in thalami. t values are shown. Voxels are shown significantly surpassing the voxel-wise threshold (p < 0.001) and the spatial extent threshold (10 voxels). Voxel-wise contrasts were performed on spatially normalised PK BP images, smoothed with a 12-mm full-width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel, using SPM5 (see [3] for details). b PK BP in the thalamus and cortical grey matter, defined using anatomical regions of interest, in TBI patients (red) and controls. Group mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown; ***p < 0.001. c Tract mask (blue) connecting the left thalamus (red) to the left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (green), produced using probabilistic tractography in healthy controls (see [12]). Fractional anisotropy (FA) was sampled using bilateral thalamo-cortical tract masks. d FA in thalamo-cortical (Thal-Ctx) body of the corpus callosum (CC) and across the white matter skeleton (Skel) in TBI patients (red) and controls; **p < 0.01

To test whether thalamic PK binding is more strongly correlated to proximal than distal thalamo-cortical damage, FA was sampled from a series of non-overlapping ring-shaped ROIs extending centripetally from the thalamus from 2 to 60-mm diameter and intersected with the thalamo-cortical tract mask. ROIs were created by repeatedly dilating a thalamic mask by two voxels (2 mm). Ring-shaped ROIs were produced by subtracting the previous mask from each step.

PK PET acquisition and analysis are described in [3]. To produce maps of PK binding potential (BPND), we used a supervised clustering procedure to identify reference clusters of voxels in grey matter having PK time activity curves mirroring those of controls [3]. PK BPND was sampled in the bilateral thalamus as well as the cortical grey matter regions that were used to define the thalamo-cortical tracts [12].

Regional PK BPND was compared between groups using independent sample t tests. Mean FA values were similarly compared. Bonferroni multiple comparisons correction was used. In TBI, we tested for a relationship between regional PK BPND and thalamo-cortical FA using linear partial correlations, controlling for age and time since injury as both factors potentially influence DTI [15] and PK binding [16].

Results

A voxel-wise contrast showed increases in thalamic PK BPND in TBI patients versus controls (Fig. 1a, reproduced from [3]). PK binding in the thalamus ROI was significantly increased (t = 4.64, df = 15, p < 0.001, Fig. 1b). In contrast, there was no difference in cortical grey matter PK binding between the groups.

FA was decreased in TBI patients versus controls in thalamo-cortical projections (df = 20, t = −3.68, p = 0.0015), the corpus callosum (df = 20, t = −3.264, p = 0.004) and the white matter skeleton (df = 20, t = −3.450, p = 0.003) (Fig. 1d).

In TBI, we found a significant negative correlation between thalamic PK BPND and mean thalamo-cortical tract FA (r = −0.770, p = 0.042). The strength of this correlation decreased with the distance at which FA was sampled from thalamo-cortical tracts (Fig. 2a). Thalamic PK binding was most strongly correlated with FA of voxels within 10 mm of the thalamus, maximally within 2-mm distance (Fig. 2b). There was no correlation between thalamic PK binding and FA of the corpus callosal tracts nor between cortical PK and thalamo-cortical FA, either when sampled as a whole or ROIs at different distances (Fig. 2c). We also found no significant correlation between time since injury and either mean thalamo-cortical FA or thalamic PK.

Correlation of thalamic microglial activation and white matter damage in relation to distance from thalamus. a Partial correlation of thalamic [11C]-PK11195 (PK) binding potentials (BP) and thalamo-cortical fractional anisotropy (FA), sampled with increasing distance from the thalamus in TBI patients. Distance of 0 mm reflects sampling from tracts involving the thalamus proper. R (red) and p values are shown, with a threshold of p = 0.05 (dotted line). b Plot of residuals after for thalamo-cortical FA (x-axis), sampled from a ring-shaped mask 2 mm from the outer border of the thalamus versus thalamic PK BP (y-axis). c Partial correlation of PK BP in cortical grey matter and thalamo-cortical FA, sampled and plotted as in a

Discussion

Axonal injury underlies many long-term problems after TBI [17]. Glia become activated at sites of injury [8, 18] but also at distant sites [19], including subcortical nuclei like the thalamus [18]. Our TBI patients showed both TAI and persistent thalamic microglial activation. For the first time in vivo, we show that the degrees of thalamic microglial activation and thalamo-cortical white matter tract damage are closely related.

Several mechanisms might underlie persistent thalamic inflammation after TBI (Fig. 3). It may be a response to focal injury. However, there was no MRI evidence of focal thalamic injury. Furthermore, there was no increase in PK binding in focal lesions [3], making a prolonged response to direct damage an unlikely explanation. Alternatively, thalamic inflammation may relate to a persistent effect of TAI. This is made more likely by the observation that activated microglia are seen at sites of TAI in acute and chronic phases [19]. The co-localisation of myelin basic protein immunoreactivity within microglia at sites of TAI suggests myelin fragments may provide a persistent trigger for inflammation [19]. The strong correlation we observed between thalamic PK binding and white matter close to the thalamus suggests a causative role for the persistent effects of TAI years after injury.

How chronic microglial activation and axonal injury may be linked after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Microglial activation (green cells) and traumatic axonal injury in thalamo-cortical white matter tracts (red areas) have been demonstrated after TBI. Sites of chronic microglial activation can co-localise with axonal abnormality (a) as well as along the entire axonal tract affected by injury. Remote from sites of primary axonal injury, microglia may be observed both in retrograde projection areas, towards the cell bodies of damaged neurons (b), and in anterograde areas (c and d). The thalamus is a highly connected structure. Thalamic microglial activation may be observed after TBI because of the high density of connections to damaged axons. The number of cortico-thalamic projections far exceeds thalamo-cortical projections. If microglial activation preferentially favours anterograde involvement, then relatively increased activation would be expected in the thalamus (c) compared to corresponding cortical areas (b)

Following experimental axotomy, microglial activation is seen in both anterograde and retrograde projection areas [5]. Hence, an inflammatory response might be expected in cortical and subcortical projection areas following TAI. Several factors may explain the lack of PK binding in cortex versus thalamus. Firstly, cortico-thalamic projections are ~tenfold more numerous than thalamo-cortical projections [20]. This asymmetry is especially relevant if there is also a difference in the magnitude of anterograde and retrograde microglial reactions to TAI, potentially a second factor. If both factors are important, then high PK binding in the thalamus rather than cortex would suggest an anterograde, rather than retrograde, reaction predominates (Fig. 3). However, a third factor is the high density of thalamo-cortical (and cortico-thalamic) neurons in thalamus versus cortex. As Banati and colleagues observe, the high density of neurons converging in the thalamus might lead to a cumulative signal that represents a “regional amplification of … widespread but sub-threshold cortical pathology” [21].

An anterograde evolution of microglial activation is seen in other conditions. After stroke, microglial activation spreads in an anterograde fashion along damaged tracts [8, 9], and the degree of anterograde activity in the brainstem has been shown to be correlated with pyramidal tract damage. Other diseases involving white matter damage, including multiple sclerosis and peripheral nerve injury [5] and another study of TBI [22], also show thalamic inflammation, suggesting the thalamus is a common “sink” of secondary inflammation in response to axonal damage, perhaps related to its dense white matter connectivity.

Whether chronic thalamic inflammation is harmful or restorative is uncertain. This question is challenging partly because the relationship between activated microglial phenotype and TSPO expression is not clear [23]. It may be that microglia’s role in synaptic plasticity may underlie much of what we have labelled “neuroinflammation” [7, 24]. How TSPO expression and microglial activation are related has recently been addressed by Banati and colleagues, who showed using TSPO knockout mice that TSPO expression and activation of microglia following injury are not mutually dependent [25].

An important limitation of the study is that it involved a small sample of patients and with a history of a single moderate-severe TBI. There is a need to replicate these preliminary findings in larger cohorts, which might benefit from investigating a wider range of diffusion metrics. Studies from animal models of repetitive mild TBI show persistent inflammation both at sites of axonal injury and locations remote from the site of focal lesions, suggesting a similar microglial response in cases of lower injury severity [26, 27].

Evidence of persistent neuroinflammation suggests that the window of opportunity for therapeutic intervention following TBI may be longer than is usually considered. Inflammatory PET imaging provides a biomarker to investigate this prolonged inflammatory reaction and potentially the effects of interventions targeting glial activation. Our findings emphasise the need for large multi-modal longitudinal studies combining inflammatory PET with diffusion MRI to image axonal injury.

Abbreviations

- BPND :

-

binding potential

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- DTI:

-

diffusion tensor imaging

- FA:

-

fractional anisotropy

- PET:

-

positron emission tomography

- PK:

-

[11C]-PK11195

- ROI:

-

region of interest

- TAI:

-

traumatic axonal injury

- TBI:

-

traumatic brain injury

References

Smith DH, Johnson VE, Stewart W. Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: substrates of dementia? Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(4):211–21. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.29.

Whitnall L, McMillan TM, Murray GD, Teasdale GM. Disability in young people and adults after head injury: 5–7 year follow up of a prospective cohort study. JNNP. 2006;77(5):640–5.

Ramlackhansingh AF, Brooks DJ, Greenwood RJ, Bose SK, Turkheimer FE, Kinnunen KM, et al. Inflammation after trauma: microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(3):374–83. doi:10.1002/ana.22455.

Frank-Cannon T, Alto L, McAlpine F, Tansey M. Does neuroinflammation fan the flame in neurodegenerative diseases? Mol Neurodegeneration. 2009;4(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-4-47.

Banati RB. Visualising microglial activation in vivo. Glia. 2002;40(2):206–17.

Cagnin A, Myers R, Gunn RN, Lawrence AD, Stevens T, Kreutzberg GW, et al. In vivo visualization of activated glia by [11C](R)-PK11195-PET following herpes encephalitis reveals projected neuronal damage beyond the primary focal lesion. Brain. 2001;124(10):2014–27.

Banati RB, Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Gunn RN, Myers R, Jones T, et al. Long-term trans-synaptic glial responses in the human thalamus after peripheral nerve injury. Neuroreport. 2001;12(16):3439–42.

Thiel A, Radlinska BA, Paquette C, Sidel M, Soucy JP, Schirrmacher R, et al. The temporal dynamics of poststroke neuroinflammation: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging-guided PET study with 11C-PK11195 in acute subcortical stroke. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(9):1404–12. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.076612.

Pappata S, Levasseur M, Gunn R, Myers R, Crouzel C, Syrota A, et al. Thalamic microglial activation in ischemic stroke detected in vivo by PET and [11C] PK11195. Neurology. 2000;55(7):1052–4.

Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;246:35–43. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013.

Mac Donald CL, Dikranian K, Bayly P, Holtzman D, Brody D. Diffusion tensor imaging reliably detects experimental traumatic axonal injury and indicates approximate time of injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27(44):11869–76. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3647-07.2007.

Squarcina L, Bertoldo A, Ham TE, Heckemann R, Sharp DJ. A robust method for investigating thalamic white matter tracts after traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage. 2012;63(2):779–88. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.016.

Hellyer PJ, Leech R, Ham TE, Bonnelle V, Sharp DJ. Individual prediction of white matter injury following traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(4):489–99.

Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage. 2006;31(4):1487–505. doi:S1053-8119(06)00138-8.

Grieve SM, Williams LM, Paul RH, Clark CR, Gordon E. Cognitive aging, executive function, and fractional anisotropy: a diffusion tensor MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(2):226–35.

Gerhard A, Schwarz J, Myers R, Wise R, Banati RB. Evolution of microglial activation in patients after ischemic stroke: a [11C](R)-PK11195 PET study. Neuroimage. 2005;24(2):591–5. doi:S1053-8119(04)00561-0.

Meythaler JM, Peduzzi JD, Eleftheriou E, Novack TA. Current concepts: diffuse axonal injury-associated traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(10):1461–71.

Maxwell WL, MacKinnon MA, Smith DH, McIntosh TK, Graham DI. Thalamic nuclei after human blunt head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(5):478–88. doi:10.1097/01.jnen.

Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 1):28–42. doi:10.1093/brain/aws322.

Jones EG. The thalamus. Springer Science & Business Media; New York 2012.

Cagnin A, Gerhard A, Banati R. In vivo imaging of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. In: Wood P, editor. Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms and Management. New Jersey: Humana Press Inc.; 2003. p. 379–85.

Folkersma H, Boellaard R, Yaqub M, Kloet RW, Windhorst AD, Lammertsma AA, et al. Widespread and prolonged increase in (R)-(11)C-PK11195 binding after traumatic brain injury. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(8):1235–9. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.084061.

Liu G-J, Middleton RJ, Hatty CR, Kam WW-Y, Chan R, Pham T, et al. The 18 kDa translocator protein, microglia and neuroinflammation. Brain Pathol. 2014;24(6):631–53. doi:10.1111/bpa.12196.

Graeber MB. Neuroinflammation: no rose by any other name. Brain Pathol. 2014;24(6):620–2. doi:10.1111/bpa.12192.

Banati RB, Middleton RJ, Chan R, Hatty CR, Kam WW-Y, Quin C, et al. Positron emission tomography and functional characterization of a complete PBR/TSPO knockout. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5452.

Shitaka Y, Tran HT, Bennett RE, Sanchez L, Levy MA, Dikranian K, et al. Repetitive closed-skull traumatic brain injury in mice causes persistent multifocal axonal injury and microglial reactivity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70(7):551–67. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31821f891.

Aungst SL, Kabadi SV, Thompson SM, Stoica BA, Faden AI. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury causes chronic neuroinflammation, changes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, and associated cognitive deficits. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(7):1223–32. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.75.

Acknowledgements

GS was supported by a clinical research fellowship awarded in the Wellcome Trust-GlaxoSmithKline Translational Medicine Training Programme. The Medical Research Council (UK) supported PH. PM has research support from the MS Society of Great Britain, the Progressive MS Alliance, the MRC and GlaxoSmithKline and personal support from the Edmund J. Safra Foundation and from Lily Safra. DJS has been supported by an MRC (UK) Clinician Scientist Fellowship and currently holds a National Institute of Health Research Professorship—RP-011-048 (DJS). The research was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

DJB has been a consultant and part-time employee for GE Healthcare in the past. He has received honoraria from Glaxo, Britannia, Zambon, Astex and GenePod. PM has consulted or received honoraria for lectures from GlaxoSmithKline, Biogen IDEC, IXICO and Novartis. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

GS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. PH contributed to the analysis of the data. AR contributed to the study design, and coordination and acquisition of data. DJB contributed to the study design and coordination and revised the manuscript. PM contributed to the study design and revised the manuscript. DS contributed to the study concept, design and coordination; acquisition of data; supervision of the study; and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, G., Hellyer, P.J., Ramlackhansingh, A.F. et al. Thalamic inflammation after brain trauma is associated with thalamo-cortical white matter damage. J Neuroinflammation 12, 224 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0445-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0445-y